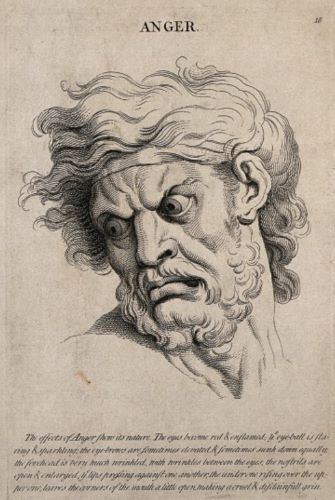

As the lists of seven deadly sins prove, anger was certainly seen as a disorder within medieval culture.

By Dr. Marko Lamberg

Professor of History

Turun Yliopisto

Introduction

In their quest to describe human faults and vices – and in order to promote their opposites, moralities and virtues – ancient and medieval theologians gradually invented the famous list of the so-called seven deadly sins. There did occur a certain variation in the composition of these listings, but orgē or ira, “wrath” or “anger,” was always among them from the fourth century onwards.1 Consequently, historians have utilised such conceptualisations when studying mentalities and emotions of the past.

In particular, anger has received a lot of attention because all human cultural evolution – the civilizing process, to use the classical term coined by Norbert Elias – can be regarded largely as a tale of socialisation, pacification and control of aggressive and violent behaviour – anger management, to use a modern psychological concept, one which has also been adopted in popular vocabulary.2 Indeed, it would be difficult to understand human culture and human history without the influence of strong negative emotions such as wrath, which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as “vehement or violent anger; intense exasperation or resentment; deep indignation.” Anger, in turn, is defined in the same source as something “which pains or afflicts, or the passive feeling which it produces; trouble, affliction, vexation, sorrow.”3 As we can see, these modern definitions stress the nature of anger as a mental disorder – it upsets a person’s inner balance, may cause social turmoil and potentially leads to sin or crime.

Of course, wrath or anger can have a great variety of more or less different definitions depending on who tries to describe them. Likewise, strong emotions can be described with the use of several other concepts as well. In modern everyday speech, anger is often connected to aggression and sometimes even understood as synonymous with it, but to psychologists, anger is an emotion, whereas aggression is behaviour – all anxiety or loss of temper does not lead to violent deeds or even to outbursts of strong words.4

In late medieval Swedish language anger was usually described as wredhe, which has the same etymology and virtually the same meaning as wrath in English; in modern Swedish it is written vrede. An affiliated term, hate, was and still is expressed by the word hat. Medieval Swedish also had the term anger, which of course originated from the same root as anger in English and which still exists in modern Swedish as ånger, but it already meant – as it still means – “anxiety” or “sadness,” even “remorse.”5 These interesting similarities and differences between English and Swedish show how people speaking Germanic languages have, during the course of time, used basically the same words when describing nuances in symptoms and reactions that were related to each other. It is not always easy to discern boundaries between different emotional states, which is why the semantic fields of these words are nowa-days not identical in affiliated languages.

As the lists of seven deadly sins prove, anger was certainly seen as a disorder within medieval culture. It was, in a practical theological context, basically a spiritual disorder because it threatened one’s salvation, but it could also be regarded as a mental disorder because it affected one’s thoughts and mental wellbeing as a whole. But did the contemporaries actually perceive a spiritual problem – a sin – also as a mental problem? If so, how did they speak of the mental consequences of anger? Moreover, despite the difference between emotion and behaviour, anger can also be regarded as a form of social disorder: even if it does not necessarily lead to aggression towards other people, it causes tension and disruption in individual relationships – if not otherwise, at least at the level of thoughts and emotions. But how was anger actually seen by medieval men and women in this respect: did they pay much attention to the social consequences of anger or did they simply regard anger as a spiritual, mental or medical problem?

Naturally, these topics have been dealt with in earlier research. Anger has also been approached as a psychological and cultural pattern in the medieval context. Earlier studies have shown how medieval societies sought to control and prevent the appearance of anger by utilising Christian theology, a context in which anger appeared as a sin, and within learned culture by means of references to the learned treatises written in Antiquity, a context in which anger also appeared as a mental disorder.6 It has also been pointed out that the medieval attitude towards the concept of anger was in fact ambiguous: whereas anger was harmful for ordinary people in everyday contexts, occasionally anger could be regarded as righteous – especially anger or wrath that was attributed to God and His saints, as well as being shown by kings. Here we see an example of a social dimension of anger: anger legitimised the authority of the mighty judge or the severe punisher.7 There even seems to have been a grey zone of anger: the emotions associated with vengeance could also be understood and accepted by theologians, although the violent act itself was usually (but not always) seen as a misdeed. The spiritual, mental and social dimensions of anger were intertwined in the concept of justifiable anger. Apparently theology had to be adapted since warfare was endemic and in addition crusades gave anger a legitimate character.8

Nevertheless, many of the earlier interpretations have been based on the writings produced within literary and more or less learned circles, and mainly in Latin.9 Can we therefore be sure that anger was explained and understood in a similar fashion in other contexts? Which of anger’s three dimensions was stressed by common medieval men and women? This essay seeks to answer these questions: I analyse how anger was depicted, which symptoms were ascribed it, what was believed to cause it and what consequences it was believed to have.

My analysis is based on a special literary genre, exemplum tales, which existed already in Antiquity. As the term itself reveals, an exemplum is a tale which contains an example – usually a warning – for the audience. Medieval preachers included clarifying and moralising tales in their sermons in order to make their message clear for laypeople. For that purpose, what could have been a better way than using a “real person” or a “true event” as an example? Tales of different origins and different ages were gathered into collections, which also circulated as translations into numerous vernaculars. Exempla also appeared in other forms of literature, not least in saints’ lives and miracles. So vivid was this genre that we can estimate that almost all Western European laypeople who ever visited a church must have heard at least one exemplum, although the concept itself almost certainly remained unknown to the majority.10

Because an exemplum had to be clear enough for the illiterate uneducated audience to understand, and because it could be mixed with elements from the culture of the lower classes, it formed a bridge between high culture and popular culture. That is why it serves well as source material for a study which analyses ideas of disorders. Of course, the interpretation available for us to research comes mostly from the literate social strata, but not even learned monks composing didactic tales in monasteries were completely isolated from the culture of the masses – after all, most of them had been born in lay families. For several reasons, exempla contain patterns that must have been shared by virtually everyone in medieval society.11

My method is derived from the study of concepts: I focus on tales that men-tion or describe anger and I analyse the terms used to describe it. Because I intend to see how anger was understood and treated in areas where Christianity was still of relatively recent origin, I focus on Northern Europe, that is Scandinavia and Finland, which were slowly Christianised from the tenth century onwards. The main source of my study is an exempla collection which was composed in the monastery of Vadstena in Sweden before the end of the fourteenth century and which was apparently used in other parts of the North as well. To gain a more profound understanding of anger as a disorder, these Northern sources are compared to more general conceptualisations of medieval culture.

I begin my study by giving a brief survey of the possibilities and limitations of the source material. After that, since exempla were usually presented as if events and experiences they describe had really happened to living people, I analyse the social and gendered structures of the person gallery in the collection of tales I am studying. Because my findings point toward an understanding that anger was perceived both as an emotional state and as a behavioural disturbance, I handle these topics in separate sections, paying special attention to the imagery dealing with the spiritual, social and mental effects of anger.

‘The Book of Wonders’

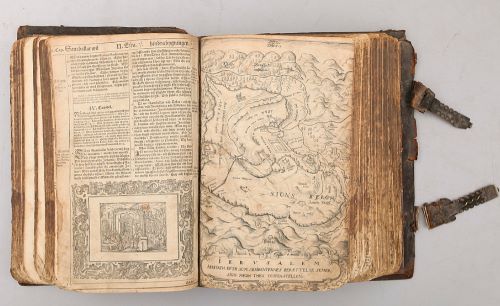

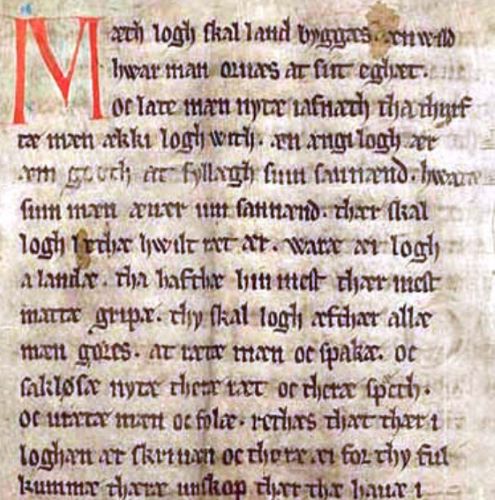

For this study, I have analysed all 192 exempla in the late medieval Swedish codex called Codex Holmiensis A 110, nowadays preserved in the Royal Library of Sweden, Stockholm. This collection, also known as Järteckensboken (The Book of Miracles/Wonders), was composed around 1385 in the Birgittine monastery of Vadstena.12 According to their Rule, Birgittine brothers were ordered to preach to lay people and to give clear and understandable sermons,13 so a collection of exempla from this monastic order should be an especially fruitful source for an analysis that aims to approach the sentiments of the wider masses. Besides that, the Birgittine monasteries were open for both sexes, so it is interesting to see if and how the double monas-tery structure is reflected in the tales and in the choice of collected (and translated) tales.

The collection has been published in a source edition by the Swedish philologist Gustaf Edvard Klemming.14 A digitalised version of this edition is accessible online via Fornsvenska textbanken.15 There exist also two shorter and later medieval versions of the same text. The shorter one belongs to the National Library of Finland in Helsinki, originating most likely from Birgittine circles, perhaps via the monastery of Naantali (Nådendal in Swedish; Vallis Gratiae in Latin). It is actually a fragment, consisting of probably eight more or less worn quarto-sized pages, most of which has been published in Klemming’s edition.16 The longer variant contains approximately 60 exempla at the end of a manuscript volume.17 The Danish variant seems to have been written by a Birgittine nun at the monastery of Maribo in the middle of the fifteenth century or slightly after that.18 There was probably at least one more Nordic copy made, for the Birgittine monastery of Munkaliv near Bergen in Norway.19

Järteckensboken and its variants are written in medieval Swedish, but the text must have originated elsewhere and in some other language. When any of its tales mentions a geographical setting by name, it always lies outside Scandinavia – in areas which nowadays belong to Germany, France, England, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece or the Near East. This is a strong indication of a non-Nordic origin: the collection was “merely” translated by the Birgittines. Although research has so far been unable to identify the original collection, some of its tales can be found in other works, including other contemporary works in Swedish.20 Because there are no references to plague in Järteckensboken, which otherwise lists a considerable number of illnesses and defects, the original collection probably derives from the era before the Black Death.

Given that the purpose of this study is to focus on Nordic mentalities, one has to ask how well the Book of Wonders, which clearly includes non-Nordic material, serves as the main source material. One answer is that it is hard to divide any works of medieval literature into “domestic” and “foreign” ones. Texts were not simply translated verbatim in the Middle Ages; instead, they were simultaneously almost always partly edited or re-written, even mixed with other texts or new sequences composed by the translator. Thus texts were adapted for the purposes of the translator-compiler or those of his or her audience. What we now understand as translation, whereby the translator seeks to be as faithful to the original wording as possible, did exist already in the medieval literary culture, but by far the most common method of transmitting the message from one language to another was to compose a paraphrase, which was freer in form and which could involve some changes in the contents.21 Bearing this in mind, Järteckensboken has great value as a medieval Nordic text, which casts light upon Nordic cultural and mental patterns of the scribe’s time. After all, the translator or translators had to utilise a lot of comparable domestic terminology to make the original terms comprehensible to Nordic audiences.

Unfortunately, the non-Nordic original text has not been found, which makes it impossible to determine to what degree the Swedish version was rephrased. It is at least possible to make a comparison between the version made in Vadstena and its two fragmentary copies and conclude that these texts are almost identical in wording – the two fragments must be direct copies of the “original translation.”22 This copying also suggests that Järteckensboken belonged to those core texts which the Birgittines in Vadstena wanted to share with their brothers and sisters in the Nordic sister monasteries.23 Most likely, the tales of this collection were intended mainly for the use of the sisters and lay brothers whose knowledge of Latin was weaker. But it is plausible that Birgittine preachers also utilised the tales when they preached to pilgrims visiting the monastery church. It can also be assumed that exempla were retold or referred to when Birgittine priest brothers gave private absolutions and reprimands.

At first reading most of the exempla in Järteckensboken seem “merely” to stress the salvation received through the Christian faith: one should live humbly and devoutly and resist the devil’s temptations, one should avoid vanity and greed, one should confess one’s sins completely, especially when one is going to partake of the Communion, one should avoid all kind of worldly working or feasting during holidays, one should not worship the Devil or exploit Christian rituals or sacraments for magical purposes, one should receive the Holy Communion, at least at Easter Mass or when one is lying on one’s sick or death bed: the list continues. Indeed, it appears as if exempla most of all reflect the worry felt by clergymen, who were apparently afraid of losing their own authority, or of the misuse of Christian emblems.

Research dealing with saints’ lives and miracles has shown, however, that religious elements were interwoven with elements of profane everyday culture and a careful examination of the tales enables us to trace structures and ideas which were not limited only to the religious sphere.24 If we analyse, for example, the tale that tells of a woman who became so angry when her baby boy soiled her clothes that she cursed him by saying: “I give you to the devil!” (tale no. 140),25 it is obvious that the tale is based on tension in parent–child relationships, actually a timeless issue. The tale is given a religious framework, but its core is banal and profane.

When we think of the role of exempla as cultural transmitters or, depending on the view, as cultural transmissions, we should not assume that they were invariably transmitted downwards in medieval society from the upper medieval social strata to the lower: the Catholic clergy was not a closed caste and it continually recruited new members from various circles of society. Those who received higher education and produced texts of their own carried with them a cultural heritage that was shared by laypeople. The results of these transmissions can also be seen in Järteckensboken, as several of its tales must have been based on oral culture – sometimes on tales which we would call “urban legends.” Some must have originated as anecdotes or even jokes.26

A collection of exempla contains tales of different origins and different forms. A single tale might have several meanings and it might be narrated in different ways. Furthermore, a preacher could stress different elements on different occasions and perhaps omit certain other elements. Moreover, the listeners – most literary works reached their audience by means of oral readings – could receive and understand the tale in their own individual ways. Allowing for these variations in form and interpretation, here I intend to make an analysis based on the message which the collection composer wanted to transmit and how he described elements in the culture surrounding him.

The Person Gallery and Its Subcategories

It is important to start with the gallery of people in Järteckensboken because, of course, it influences the contents of the tales. Although the collection was composed in a monastery and used mainly within the religious sphere, most of its tales are set outside churches and religious houses. Even if priests and members of the religious orders appear in most tales, they do not always have such a central role in the tale that they can be regarded as main characters. In fact, most tales centre around laypeople. In several tales we can trace an antagonistic relationship between the clergy and a soothsayer, clairvoyants and healers who are depicted as witches, and magicians and devil worshippers. Usually in such tales, a clergyman makes a brief appearance in the role of absolver, or he helps in some other way by utilising the powers of the holy Church.

If we look at the societal backgrounds of the characters, the world of Järteckensboken includes all social strata, from the poorest to kings, emperors and popes. On occasion, people on the margins, such as Jews and forest bandits, figure in the tales. When the events take place outside Europe or on its frontiers we may also meet heathens. But the usual character seems to belong to the upper rungs of Western European society: if he is a member of the religious estate, he is either a priest or a monk; if he is a layman, he is either a noble or a burgher. The peasant stratum – the vast majority of the population in Sweden and other parts of Western Christianity – is clearly underrepresented: in fact, the peasants are almost invisible by comparison with those characterised as poor. This is one explanation for the lack of references to manual labour in the tales. One tale (no. 154), which recounts the assimilation problems of a nobleman who has entered a monastery, states (and now we are perhaps dealing with an addition made by the Birgittine translator) that it was then – that is, in the distant past – a custom that the monks worked with their hands.27

Most characters in the tales are male. In only about 20% of the tales do we meet both men and women. But not all characters are equally important. If we concentrate on those characters who seem to dominate individual tales or who experience the described events, it is usually a male or a couple of males around whom each tale is centred. Of the 192 exempla in Järteckensboken, 140 are centred around male characters. Only 29 can be said to have a female central character. Thus the male-centred worldview becomes ever more evident. Then there are approximately twenty tales, where it is difficult to divide characters into central and supporting ones.

Without doubt the uneven gender distribution reflects the generally more active role of men in late medieval society: after all, men have left more record of themselves in the extant literary sources of medieval Europe. Of course, even if the central character of a tale is male and belongs to a certain social group, the message may still have been directed to the opposite sex and people belonging to other social strata. On the other hand, the reader or listener who was socially closer to the character is more likely to have identified with him or her. Moreover, it is important to pay attention to the relationship between the themes and the characters used to explicate them. For example, as we have already seen, it was a mother and not a father who became angry with a baby boy in tale no. 140.

Anger as an Alienating Factor

Wredhe appears in nine tales of Järteckensboken.28 Its connotations are never clearly defined, except in tale no. 157, where wredhe is mentioned alongside säwyrdha, “disrespect,” as a counterpart to kärlekir, “love.”29 In other cases, the meanings of the term can be deduced on the basis of its context. Besides these nine tales, there are some others depicting similar problems and emotions, although the term wredhe is not used; as appears below, such tales may be used for comparison and deeper contextualising.

In three other tales (nos. 117, 161 and 181) the term wredhe does not refer to human anger, but instead either to God’s wrath or Satan’s wrath.30 In these cases it is a question of supernatural, authoritative wrath and a human being or the wrongdoer is its object. Such tales strengthen the idea of anger as some-thing originally inhuman.

In the first Järteckensboken tale that deals with human anger, no. 29, a woman who is suffering from “great impatience [or anxiety] and anger” goes to church in order to hear the mass “before the anger left her.”31 The formulation reveals that anger was seen as something that could leave a person, at least temporarily. In other words, we come across the idea that anger originates from a sphere which lies outside the human body and mind. It should also stay there: the angry woman in the tale finds out that she is unable to see the Eucharist. Medieval audiences were certainly supposed to be shocked at this point, as the holy bread was also the Body of Christ and it was the most intimate bond between human beings and God.32 The angry individual was thus in danger of spiritual alienation, but there was also a risk of alienation from the Christian community.33 The symptom the angry woman is suffering from has sometimes been labelled “hysterical blindness” in later psychology.34 Here we probably have an indication that there was a recognition that emotions could cause somatic reactions in medieval culture.

Thus, the first tale in which anger is spoken of seems to transmit ideas, according to which anger was a spiritual and social as well as a mental disorder. But it was still possible for such an angered individual to change his or her state of mind and be healed and saved. Consequently, the angry woman confesses her sin – anger is indeed called a sin here – and she feels remorse and wants to receive absolution. Then she sees the Eucharist again, this time in the shape of a beautiful boy child. This vision was relatively common in the Late Middle Ages.35 The woman recovers as she gets a lot of “spiritual satisfaction and sweetness.” As Moshe Sluhovsky has noted, spiritual feelings could – in fact, had to – be described with the use of a very corporeal vocabulary.36

The reason for the woman’s anger is not specified in the tale, but it is clear that anger per se is depicted as something harmful which should be avoided. Because exempla in their written forms represent the culture of the clergy it is understandable that the tale ascribes the power and the merit of healing the angered mind to the Church.

In tale no. 129 there is another angry woman, the wife of a pious knight. In this case we are given the reason behind the anger: she wrongly suspects that her husband is visiting other women.37 But instead of asking him to explain where he goes every morning, she constantly behaves in an “anxious and angered” manner, not only with him but with everyone else too. Thus anger is depicted as a disorder that makes an individual a burden to other people. Finally, when the knight feels that he cannot tolerate her anymore, he asks her to go away, telling her that he loves another more, one who is “better, more beautiful and richer.” Hasty and provocative words lead to a hasty over-reaction: the wife takes the knight’s knife and stabs herself, killing both herself and her unborn child. But the tale has a happy ending nevertheless. The knight goes to church and kneels down and prays in front of the statue of Virgin Mary, whereupon the Virgin raises his wife from the dead. She hurries to the church and admits that the woman her husband loves – that is, the Virgin Mary – is indeed more beautiful and better than she, as well as above all created things.

The wife is depicted as solely responsible for her anger, because she does not want to hear any explanations from her husband – in other words, she is clearly guilty of unfounded anger. As in the previous tale, here it is hinted that the rightful place of one who is angered is outside the sacred space: the suspicious wife does not enter the church until she has been revived both physically and spiritually, and has thus become free from her anger. However, the character of anger as a mental disorder is not openly stated – we can assume that the woman’s behaviour and the hasty suicide were interpreted as signs of mental unbalance by medieval preachers or their audiences, but we cannot be certain.

As we have already seen, in tale no. 140 the warning against an angered state of mind is given in a shape of a female figure, when a mother curses her little son because of her soiled garments.38 This tale apparently warns its audience against getting angry because of minor everyday setbacks, which is why the ill-considered and disproportionately severe curse causes the mother to be haunted by devils day and night. Moreover, her child does not want to see her again, so he has to be raised by another woman. The haunted mother, in turn, is unwilling to hear mass or anything about God – once again a hint that anger and sin were linked. It is possible to regard the mother’s stubbornness as a sign of some form of mental disorder, such as depression, but once again we cannot be sure of this. What is evident is the image of anger as something which alienates the individual from her surroundings, especially from the Christian community.

In the above tales, anger alienates women from other Christians and also from their own families. It undermines the ideal image of women as obedient wives and loving mothers and makes them turn against their husbands and their children. But probably more serious from the clerical perspective was the spiritual alienation and the risk of damnation. Nevertheless, it has to be stressed, on the basis of the above examples, that angry people were apparently believed to have some hope of mercy if they relied on heavenly powers. This holds true also for the mother in tale no. 140: she finally regrets her sin and prays to the Virgin Mary. Thus she is freed from the devils (and her anger) and can be reunited with her son.

In tale no. 178 conscience is said to have different colours depending on the quality of life: the dark shades belong to those who commit serious sins and the “bloody ones” (blodhoge) to those who are jealous, angry or full of hate, whereas the light ones stands for virginity and purity.39 Black and white are natural opposites to each other, but the colour of blood stands out – the “blood-ied ones” are not damned souls, but they are not completely pure either. It is symptomatic that strong negative emotions have been connected to blood and the colour of red – perhaps here we see the influence of the doctrine of human temperaments and the concept of sanguinity.40 The role of blood in religious and medical thought was ambiguous: it was not only a symbol of danger or defects, physical or spiritual, but also an instrument of purification. A man whose blood was let was believed to be healed and likewise a menstruating woman was at the same time unclean and undergoing a purification process.41 Thus angry people were not depicted in black or regarded as doomed – they were in a liminal state and had the option to proceed either towards healing or towards destruction.

Anger as a Source of Aggression

Some tales in Järteckensboken deal with the violent outcome of anger. As noted above, anger and aggression are regarded as separate phenomena within mod-ern psychology, although they can be linked to each other. A violent action is often preceded by anger. Violence, in turn, may cause anger. This view was evi-dent also in medieval legislation. For example, the Swedish Law of the Realm (Landslagen) from the middle of the fourteenth century spoke of violence as wredhs wærk “works of wrath.” The cause behind violence could, in turn, be regarded as wredhs wilia “the will of wrath.”42 The last mentioned concept seems to be present in Järteckensboken. In tale no. 44, which belongs to a sub-collection devoted to miracula de nomine ihesu, “miracles of the name of Jesus,” we hear of a man who aims to kill his enemy because of the injuries the man has done to him.43 In other words it is clearly an act of aggression – revenge – in the making. As noted earlier, medieval theologians had an ambiguous attitude towards sentiments connected to revenge, an emotion which could at least be tolerated.

The vengeful man in tale no. 44 had apparently made his plans known to those around him, because we read that many people pleaded that he show mercy for God’s sake. Two of these were clergymen, but the man is unwilling to listen to their pleas – once again we have the image of anger as a state of mind which lasts for a long period and prevents an individual from leading his life according to Christian values and norms. Finally, one of these two clergymen writes the name of Jesus Christ on the vengeful man’s forehead “and immediately his anger disappeared so that he settled himself fully with his enemy.” The vengeful man thus becomes healed – by the touch of a pious man who uses the name of Jesus Christ as an amulet, albeit most likely invisible. Plausibly, contemporaries understood this phrase so that the clergyman – a priest, an ordained monk or a mendicant brother – made the IH and XP signs (or at least one of them) with his finger on the vengeful man’s skin, instead of actually writing the complete name of Jesus Christ in ink. If any writing material was implied, it was most likely Chrism or some other holy oil used to heal sick people, or in cases of exorcism.44 More important is the place where the sign is “written”: the healing act is focused on the forehead, because the seat of anger, apparently, was behind it, inside the head. As we have already seen, in the case of the angered woman in tale no. 29, it was also the head that was affected, as the woman was suddenly unable to see the Eucharist.45

Tale no. 44 bears some resemblance with nos. 58 and 59: in the first two brothers are seeking revenge upon a man who has killed their father and in the other two a man is seeking revenge upon another who has killed his brother.46 But anger is not explicitly mentioned. In both cases the act of killing is about to be carried out on one of the holiest days, Good Friday, but the deed is prevented by God. In a climax which occurs in a church, the avengers make friends with their enemies and the statue of the crucified Christ bows in front of the merciful men. These tales suggest that forgiveness (and liberation from anger) ultimately lay in the hands of God. In other words, anger could be depicted as an incurable disorder, of which a human being could not necessarily be rid without assistance from God or His representatives.

It is noteworthy that killings – aggressive actions towards other people – are always planned by male characters, whereas it can be argued on the basis of the tales discussed above that women’s anger was envisaged as appearing in less violent forms: as verbal aggression, intolerable behaviour, mental disorder or even suicide, but not as murder, unless the suicide of the knight’s wife is regarded as an infanticide because she simultaneously killed her unborn child. In that case, however, it is not stated that she had planned the action beforehand – on the contrary, it was a mode of spontaneous aggressive behaviour that seems to be regarded as typical for women. It is not uncommon to find gendered messages in medieval readings: certain grave sins, such as lust and greed, were especially associated with women.47 Moreover, medieval literature tended to depict women as emotionally more unstable than men. Such ideas stemmed partly from medical ideas regarding the female physiology, but even behind learned interpretations there must be a suspicion of patriarchal ideology, since most literary works were written by men.48

Although the sample analysed here is relatively small, it is significant that tales involving open outbursts of anger most often seem to have been told by means of female examples. The mentalities in Järteckensboken have some resemblance to high medieval German law texts and works of fiction that linked negative emotions mainly to women and heroic anger mainly to men.49 Perhaps this patriarchal, gendered worldview was one of the reasons why Birgittine brothers in Vadstena Monastery decided to translate this collection into Swedish: after all, the majority of the listeners were women, because nuns far outnumbered brothers.50 However, no tale of anger actually told of an angry clergyman or nun. All the role models and warning examples were in the guise of laymen and laywomen. Men and women of religious orders are present in some of the tales which deal with disobedience and other matters. As regards the angry characters, very little is said of their social backgrounds, with the exception of two knights and the wife of a knight. The absence of titles probably helped listeners to identify with the characters, as these remained merely men, women, wives and other relatives. However, references to knightly families would not necessarily prevent the audience from identifying with the examples, at least not among the sisters’ convent of the Vadstena Monastery, because more than one in four nuns came from aristocratic families.51

One form of aggression has usually been held as a sign of mental disorder in medieval as well as in modern thought. The Catholic Church regarded – as it still regards – suicide as a grave sin and according to modern psychological theories, suicide can also be interpreted as aggression and an ultimate consequence of anger.52 Besides the tale of the pious knight and his hot tempered wife, three other tales deal with suicide. In tale no. 93 we meet another wife in an almost identical situation to that of the knight’s wife, although anger is not mentioned as such: instead, the woman is despairing because her husband has relationships with fallen women and she wants to kill herself. One day she decides not to follow other people to the mass but stays at home and, “on an impulse from the Devil,” attempts to drown herself. The idea of spiritual and social alienation is indeed very clearly stated in this tale. Miraculously, her body does not sink, but instead floats down the river, thanks to her devoted-ness to the Virgin Mary.53 This tale seems to indicate that an emotional burden may bring about suicidal thoughts and even a suicide attempt. Sorrow as an explanation for the attempt is quite clearly described in this tale.54

Although ideas associated with anger are discussed largely by means of female characters in Järteckensboken, suicide is dealt with in a more balanced way regarding the gender ratio, since the other two stories related to this dark topic are told by means of male characters. The degree to which mental burden is explored varies: a man jumps into the water and he is said to be too depressed to live because of worldly (or corporeal, as likamlika could have also that meaning) setbacks, but when we hear of a knight who attempts to drown himself, his motivations are not clarified at all.55 As in those discussed above, in these tales the mentally burdened individual is saved miraculously: the scribes apparently felt it was safer not to give people too many negative examples, especially when such a taboo matter as suicide was handled, and decided instead to encourage their audience to be patient with their faith.

It must be stressed that only one of the four tales dealing with suicide states openly that anger is the main emotion behind the attempt, namely the tale of a pious knight and his disturbed wife. Apparently it was easier to connect suicide – an act which was directed against oneself – with sorrow and grief, whereas anger was regarded more as an emotion that would lead to attacks on other people.

Conclusions

As the brief comparison between the concepts of anger and ånger and their equivalents at the beginning of this essay showed, unbalanced states of mind are not easy to identify as the boundaries between different emotions and their symptoms are unclear. But medieval minds sought to analyse and understand the nature of anger, at least in order to avoid, suppress or tame it. The tales in the Book of Wonders, which in many ways combined popular beliefs with learned theology, reflect the idea that anger was most of all a sin, that is, a spiritual disorder, because anger prevented the affected person from leading his or her life according to the Christian norms and ideals. This characterisation is very understandable in the light of our knowledge of the origins of the exempla collection: it was written down at the monastery of Vadstena and it was most likely an adaptation of some already existing collection composed by members of the clergy in Central or Southern Europe.

But the image of anger was not entirely black; according to several tales, it did not necessarily lead to damnation, as divine mercy was available even for those who succumbed to it. Anger was more like a liminal state, a risk zone. Its origins seem to have been unclear: some tales do mention plausible reasons, such as jealousy or the killing of a near relative, but where the anger actually came from and where it went were questions that the exempla did not seek to answer, at least in the collection studied. Nevertheless, two conclusions as to the character of anger may be drawn from the tales: it was an unwanted element in human beings and it created distance, not merely between God and the angered individual, but also between people.

The social consequences of anger were handled or at least touched upon in several tales: an angry individual became alienated from his or her fellow Christians, even from the nearest family members. He or she could be a burden or even a threat to other people. Anger was thus regarded also as a serious social disorder. Probably this is why violent actions carried out during bouts of anger formed a category of their own in late medieval Swedish legislation, as noted earlier. No doubt there existed similarities in mentalities between different parts of medieval Europe, which must have facilitated the reception of the exemplum tales among the Northerners.

In some tales anger also appears as something that we might call a mental disorder, and it seems that medieval men and women too perceived anger as a factor which affected one’s state of mind in a negative way. In some cases the choice of words hints at this: an angry individual is simultaneously characterised as impatient or sad, or he or she suffers from devils’ torments night and day. However, we must be aware of the fact that our own cultural background influences our interpretations. We can interpret the angry woman’s blindness in the church as a psychosomatic reaction to stress, for instance, and likewise we can regard the angry mother’s long separation from her child, as well as the continuous haunting of the “devils,” as expressions of deep depression which was probably launched by guilt, and perhaps also aggressive feelings, because she felt that she was unable to fulfil the expectations as a good, loving and tolerant mother. But clearly we cannot be certain that medieval listeners understood the tales in that way. Probably there were those who were satisfied with the explanation that anger was a grave sin.

The tales in Järteckensboken incorporate general European ideas in that they tend to regard anger as an especially female vice. Men too can get angry, but in such cases they always have a cause for their emotional state – they are planning to avenge an injury that had been done to them or to their nearest ones. As noted earlier, anger in cases of righteous vengeance could at least be understood, and even tolerated, by medieval theologians. By contrast, angry women are depicted merely as acting hot-headedly and impatiently in everyday situations – they are angry “without a cause.” Here we can sense traces of the patriarchal stereotypical imagery that also characterised Western European theology and learned culture in general.

The idea of uncontrolled anger which can generate harmful bodily reactions and cause destruction to other people was no doubt also an expression of general European ideology. As a consequence of their nature as an aspect of Christian culture, exempla stress the significance of personal devotion for acquiring a cure. Medieval anger appears as something which could and should be controlled and managed. If the individual was unable to do so, he or she might get help from God Almighty or His representatives. If we think carefully about the main characters in the tales discussed above, not all of them ended up with an improved quality of life in the context of the written narrative: for example, the woman who had been blinded because of her anger got her sight back, but nothing is said about the matters that had made her angry in the first place. Did the conditions of her life change? What was the case with those who tried to commit suicide, but were prevented from doing so – were they happier afterwards? These are questions we cannot know the answers to. Perhaps medieval men and women also pondered these questions when they heard the tales; perhaps the priests, monks and mendicant brothers had to invent additions to the tales, if some among their audiences wanted to know more. Faith, patience, remorse, hope or forgiveness seem to have been the best aid or medicine offered in these tales – or the best the clergymen who told them could offer to their listeners.

Of course, in the late medieval North there may still have been individuals who did not share the explanations given by the Catholic Church. The members of the Birgittine Order belonged to those strata which were heavily influenced by general European cultural patterns – they lived their lives surrounded by a vast amount of literature of Central or Southern European origin, so it must have been easier for them than for common laypeople to comprehend the message in foreign exempla, especially after the tales had been translated into the vernacular. But in parts of Scandinavia and Finland many households and communities were remote from monasteries, churches and preachers. We cannot know if they ever heard exempla like those included in Järteckensboken, nor how they perceived the behaviour that Järteckensboken linked to anger. Nevertheless, in principle they too were targets of the tales, and their more Europeanised contemporaries most likely took it for granted that they would understand the tales – at least after their contents had been explained to them.

Endnotes

- See, for instance, Morton W. Bloomfield, The Seven Deadly Sins: An Introduction to the History of a Religious Concept, with Special Reference to Medieval English Literature (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1952); Siegfried Wenzel, “The Seven Deadly Sins: Some Problems of Research,” Speculum 43 (1968): 1–22; Richard Newhauser, “Introduction: Cultural Construction and the Vices,” in Seven Deadly Sins: From Communities to Individuals, ed. Richard Newhauser (Boston: Brill, 2007), 1–17.

- Barbara H. Rosenwein, “Introduction,” in Anger’s Past: The Social Uses of an Emotion in the Middle Ages, ed. Barbara H. Rosenwein (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998), 2–3. William V. Harris, Restraining Rage: The Ideology of Anger Control in Classical Antiquity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), esp. ch. 1; Nicholas Wade, Before the Dawn: Recovering the Lost History of Our Ancestors (London: Penguin Books, 2006), esp. ch. 8.

- “Oxford English Dictionary,” accessed 31 January 2012. http://www.oed.com (access to the full online features requires a subscription). “Wrath” and “anger” are also given other but relatively similar descriptions in this source.

- See, for example, Raymond Tafrate & Raymond Chip DiGiuseppe, Understanding Anger Disorders (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 19–25, 59.

- “Fornsvenska lexikaliska databasen,” accessed 31 January 2012. http://spraakbanken.gu.se/fsvldb/. This is an online dictionary of medieval Swedish; the explanations are given in modern Swedish.

- See, for example, Barbara H. Rosenwein, ed., Anger’s Past; Simo Knuuttila, Emotions in Ancient and Medieval Philosophy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), and Vengeance in the Middle Ages: Emotion, Religion, and the Discourse of Violent Conflict, ed. Susanna A. Throop & Paul R. Hyams (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010). The link between excessive emotions and sin was occasionally emphasized in cases of demonic possession as well; see the chapter of Sari Katajala-Peltomaa in this compilation.

- Catherine Peyroux, “Gertrud’s Furor: Reading Anger in an Early Medieval Saint’s Life,” in Anger’s Past, 36–55; Gerd Althoff, “Ira Regis: Prolegomena to a History of Royal Anger,” in Anger’s Past, 59–74, and Paul Hyams, “What Did Henry III of England Think in Bed and in French about Kingship and Anger?,” in Anger’s Past, 92–126.

- Susanna Throop, “Zeal, Anger and Vengeance: The Emotional Rhetoric of Crusading,” in Vengeance in the Middle Ages, 178, 186–187.

- There are certain exceptions, such as Paul Freedman, “Peasant Anger in the Late Middle Ages,” in Anger’s Past, 171–188 and Britt-Mari Näsström, Bärsärkarna: Vikingatidens elitsoldater (Stockholm: Norstedt, 2006).

- See, for example, Hjalmar Crohns, Legenden och medeltidens latinska predikan och “exempla” in deras värdesättning av kvinnan (Helsinki: Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, 1915); Anne Riising, Danmarks middelalderlige prædiken (Copenhagen: Institut for Dansk Kirkehistorie, 1969); Jacques Berlioz and Marie Anne Polo de Beaulieu, ed., Les Exempla médiévaux: Introduction à la recherche, suivie des tables critiques de l’Index exemplorum de Frederic C. Tubach (Carcassone: Garae/Hesiode, 1992); Jacques Berlioz and Marie Anne Polo de Beaulieu, eds., Les exempla médiévaux: Nouvelles perspectives, actes du colloque de Saint-Cloud, 29–30 septembre 1994 (Paris: Honoré Champion, 1998); Marek Tamm, “Exempla and Folklore: Popular Preaching in Medieval Estonia and Finland,” in Studies in Folklore and Popular Religion, Vol. 3, ed. Ülo Valk (Tartu: University of Tartu, 1999), 169–183, and Jussi Hanska, “Exemplum historiakirjoituksessa: Miten keski-aikaista exemplum-materiaalia on tutkittu ja miten sitä tulisi tutkia,” in Esimerkin voima, ed. Liisa Saariluoma (Turku: Kirja-Aurora, 2001), 85–101.

- This cultural interaction is discussed, for example, in Joseph Szövérffy, “Some Notes on Medieval Studies and Folklore,” Journal of American Folklore 73 (1960): 239–244; Aron Gurevich, Medieval Popular Culture: Problems of Belief and Perception, trans. János M. Bak and Paul A. Hollingsworth, Cambridge Studies in Oral and Literate Culture, Vol. 14 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989); Jürgen Beyer, “On the Transformation of Apparition Stories in Scandinavia and Germany, c. 1350–1700,” Folklore 110 (1999): 39–47, and Carl Watkins, “‘Folklore’ and ‘Popular Religion’ in Britain during the Middle Ages,” Folklore 115 (2004): 140–150.

- The collection consists of fol. 45v–122v in KB Codex Holmiensis A 110.

- Lennart Hollman, ed., Den heliga Birgittas Reuelaciones extrauagantes, Samlingar utgivna av Svenska Fornskriftsällskapet, Series 2: Latinska skrifter, Vol. 5 (Uppsala: Svenska Fornskriftsällskapet, 1956), 133.

- Gustaf Edvard Klemming, ed., Klosterläsning, Samlingar utgivna av Svenska Fornskriftsällskapet, Samlingar utgivna av Svenska Fornskriftsällskapet, Serie 1: Svenska skrifter, Vol. 22 (Uppsala: Svenska Fornskriftsällskapet, 1877–1878), 4–128. With the exception of a sub-collection dealing with miracles attached to the name of Jesus Christ, the tales are not numbered. The numbers used in this study derive from Klemming’s edition. In the manuscript codex, only tales forming two sub-collections dealing with miracles attached to the Body of Christ and the name of Jesus Christ are numbered.

- “Fornsvenska textbanken,” accessed 31 January 2012. http://project2.sol.lu.se/fornsvenska/. This comprehensive database contains digitalized editions of a considerable number of literary works written in medieval Swedish.

- Thanks to Dr Jesse Keskiaho I was able to find a fragment of a variant of Järteckensbokenat the National Library of Finland in Helsinki. For some reason, this fragment is not included in Klemming’s edition, although it belonged to the collections of the Helsinki University Library (nowadays the National Library of Finland) and Klemming was aware of a “Finnish” variant and included four pages of it in his edition (Klemming, Klosterläsning, 430–434). So far, I have not been able to find those pages published by Klemming – they are not part of the fragment I was able to study, although they most likely originate from the same variant. According to Klemming, they should be found at the National Library.

- Cod. AM 787 quarto in the Arnamagnean Collection in Copenhagen.

- Roger Andersson, ed., Sermones sacri Svecice: The Sermon Collection in Cod. AM 787 4°, Samlingar utgivna av Svenska Fornskriftsällskapet, Serie 1: Svenska skrifter, Vol. 86 (Uppsala: Samlingar utgivna av Svenska Fornskriftsällskapet, 2006), 22–23. Andersson is referring to a dating given by Brita Olrik Frederiksen.

- The total number of preserved, known Nordic manuscripts of Järteckensboken is three.

- Sam. Henning, ed., Siælinna Thrøst, Samlingar utgivna av Svenska Fornskriftsällskapet, Serie 1: Svenska skrifter, Vol. 59 (Uppsala: Svenska Fornskriftsällskapet, 1954).

- Alastair J. Minnis, Medieval Theory of Authorship: Scholastic Literary Attitudes in the Later Middle Ages (London: Scholar Press, 1984), esp. 94. The mixtures of domestic and foreign elements in medieval Swedish manuscript codices are presented in Jonas Carlquist, Handskriften som historiskt vittne: Fornsvenska samlingshandskrifter – miljö och funktion, Runica et mediævalia, Opuscula, Vol. 6 (Stockholm: Sällskapet Runica et mediævalia, 2002).

- Also Klemming’s edition of Codex Holmiensis A 110 is very accurate.

- On Birgittine monasteries in the North in the Middle Ages, see, for example, Hans Cnattingius, Studies in the Order of St. Bridget of Sweden, Vol. 1: The Crisis in the 1420’s, Stockholm Studies in History, Vol. 7 (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1963); Tore Nyberg, Birgittinische Klostergrundungen des Mittelalters, Bibliotheca Historica Lundensis, Vol. 15 (Lund: Gleerup, 1965).

- See, for example, Christian Krötzl, “Religion and Everyday Life in the Scandinavian Later Middle Ages,” in Norden og Europa i middelalderen, ed. Per Ingesman and Thomas Lindkvist, Skrifter udgivet af Jysk Selskab for Historie, Vol. 47 (Århus: Jysk Selskab for Historie, 2001), 203–215, and Sari Katajala-Peltomaa, Gender, Miracles and Daily Life: The Evidence of Fourteenth-Century Canonization Processes (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009).

- KB Cod. A 110, fol. 101v. See also note 39.

- See, for example, tale no. 39, where a small boy misunderstands the sacrament of the Eucharist, which could be depicted by means of a beautiful boy child in medieval imagery (we read of a similar case in the tale no. 29), and becomes afraid that the priest will eat him too. KB Cod. A 110, fol. 61r–61v.

- KB Cod. A 110, fol. 105v.

- KB Cod. A 110, fol. 59r, 63r–63v, 92v, 98r–98v, 101v, 107r, 109r–110r, 116r, 117v–118v.

- KB Cod. A 110, fol. 107r.

- KB Cod. A 110, fol. 92v, 109r–110r, 117v–118v.

- “En quinna drøfdh aff myklo othuli ok wredhe gik til kyrkio at høra mæsso før æn wredhin forgik hænne Hon læt vp sin øghon tha gudz likame lyptis viliande se han ok fik engaled-his see han Tha kændis hon widhir sina synd ok tok sik idhrugha for sina wredhe wiliande gerna scripta sik ok gik sidhan til annat altare hwar annar præstir sagdhe mæsso ok fik ther se gudz likama j wænasto smaswens liknilse ok fik ther aff mykin andelikin hugh-nadh ok søtma.” KB Cod. A 110, fol. 59r.

- Miri Rubin, Corpus Christi: The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

- Melvin Seeman, “On the Meaning of Alienation,” American Sociological Review 24 (1959): 783–791; Anette Erdner, Annabella Magnusson, Maria Nyström and Kim Lützén, “Social and Existential Alienation Experienced by People with Long-Term Mental Illness,” Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 19 (2005): 373–380.

- See, for example, Richard A. Bryant and Kevin M. McConkey, “Functional Blindness: A Construction of Cognitive and Social Influences,” Cognitive Neuropsychiatry 4 (1999): 227–241.

- Cf. Rubin, Corpus Christi, 135–138.

- Moshe Sluhovsky, “The Devil in the Convent,” American Historical Review 107 (2002): 1399–1400.

- “En gudhlikin riddare plæghadhe hwaria nat ga til ottosang for iomfru marie hedhir Hans hustru hafdhe han misthænktan at han ginge wanlika til nokra andra quinno. ok wilde enga orsakan aff hanom hawa vtan tedhe sik badhe hanom ok androm alt tidh drøfdha ok wredha. Ok thæntidh han gat hona met engo hughnat badh han hona ga fran sik ok sag-dhe sik ælska andra bættra ok fæghre ok rikare Ok wilia engaledhis forlata at ælska hona aff allo hiærta. Hustrun hørdhe thet ok grep sins bonda kniff ok stak sik ginstan gønom weka liwit ok drap badhe sik ok sit barn som hon hafdhe tha j liweno Riddarin wardh illa widh at hans hustru hafdhe dræpit sik for hans ordha sculd ok gik til kyrkio ok stodh a knæm a bønom for iomfru marie bilæte til thæs iomfru maria vpreste hans hustru aff dødh hulkin ginstan lop til kyrkionna til hans ok sagdhe sant wara at then frun som han ælskadhe war mykit fæghre ok bættre æn hon ok hedhirlik owir al skapadh thing Hulkin hona vpreste aff dødh met sinom bønom for hans ælskogha Ther æftir fødde riddarans hustru liwande barn ok lifdho sidhan j gudhliko liwirne.” KB Cod. A 110, fol. 98r–98v.

- “En quinna wredhgadhis mot sinom spædha son Thy at han giordhe oren hænna klædhe. ok sagdhe til hans Jak andwardha thik diæflinom Ok ginstan greps hon aff diæflinom ok møddis hardhlika dagh ok nat Ok barnit stygdis swa mot modhorinne at thet wilde ald-righ se hona vtan wænde alt tidh sit ænlite fran hænne ok vpfostradhis aff andre quinno, quinnan som møddis aff diæflinom wilde aldrigh høra mæsso ælla nakat aff gudhi, Vm en pingizdagha dagh fik hon idhrugha for sina synde, ok andwardhadhe sik ødhmiuklika iomfru marie, ok wardh quit aff diæflinom ok tok atir til sik sin son, hulkin gladhlika kæn-dis widh hona ok bleff gerna met hænne.” KB Cod. A 110, fol. 101v.

- KB Cod. A 110, fol. 116r.

- Scholastic medicine based on ancient humoral theory considered humoral imbalance as the main reason for mental disorders and illnesses in general as is exemplified in Joutsivuo’s chapter. The amalgam of humoral theory and local culture in interpretation of mental disorders can be found in Icelandic Family Sagas as well; see the chapter of Kanerva in this compilation.

- Elizabeth Robertson, “Medieval Medical Views of Women and Female Spirituality in the Ancrene Wisse and Julian of Norwich’s Showings,” in Feminist Approaches to the Body in Medieval Literature, ed. Linda Lomperis & Sarah Stanbury (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993): 145–149.

- C.J. Schlyter, ed., Corpus Iuris SueoGotorum Antique: Samling af Sweriges Gamla Lagar, Vol. 10: Codex Iuris Communis Sueciae Magnæanus: Konung Magnus Erikssons landslag (Lund: Berglingska boktryckeriet, 1862), 13, 311–312, 323, 331.

- “En wilde ændelika dræpa sin owin for the brut som han hafdhe giort mot hanum Mange badho han hawa miskun ok spara hanum for gudz sculd ok han wilde engaledhis Twe renliwis mæn komo ok badho som flere ok tha han wilde engaledhis them høra Skreff annar thæn renliwis mannin ihesu christi nampn j hans ænlite Ok ginstan forgik hans wredhe swa at han sætte sik fulkomlika met sinom owen.” KB Cod. A 110, fol. 63r–63v.

- Christopher A. Jones, “The Origins of the ‘Sarum’ Chrism Mass at Eleventh-Century Christ Church, Canterbury,” Mediaeval Studies 67 (2005): 219–315.

- Cf. See, however, Kanerva’s chapter for Icelandic views of the heart as the mind organ that housed emotions.

- KB Cod. A 110, fol. 66v–67v.

- Ruth Mazo Karras, “Gendered Sin and Misogyny in John of Bromyard’s ‘Summa Predicantium’,” Traditio 47 (1992): 241–242. Gendered structures in literary works produced in the Birgittine monastery of Naantali are discussed in Marko Lamberg, “Authority through Gendered Role Models: The Case of Late Medieval Monastic Literature at Naantali,” in Saint Birgitta, Syon and Vadstena: Papers from a Symposium in Stockholm 4–6 October 2007, ed. Claes Gejrot, Sara Risberg and Mia Åkestam, Kungl. Vitterhets historie och antikvitets akademien, Konferenser, Vol. 73 (Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets historie och antikvitets akademien, 2010), 200–215.

- Lisa Perfertti, “Introduction,” in The Representation of Women’s Emotions in Medieval and Early Modern Culture, ed. Lisa Perfetti (Gainesville: University Press, 2005), 2, 4–5.

- Sarah Westphal, “Calefurnia’s Rage: Emotions and Gender in Late Medieval Law and Literature,” in The Representation of Women’s Emotions in Medieval and Early Modern Culture, ed. Lisa Perfetti (Gainesville: University Press, 2005), 165, 171, 184.

- The number of men is discussed in Nyberg, Klostergründungen, 228–231.

- Curt Wallin, “Vadstenanunnornas sociala proveniens,” in Birgitta, hendes værk og hendes klostre i Norden, ed. Tore Nyberg, Odense University Studies in History and Social Sciences, Vol. 150 (Odense: Syddansk universitertsforlag, 1991), 291–322.

- Kenneth R. Conner, Paul R. Duberstein, Yeates Conwell and Eric D. Caine, “Reactive Aggression and Suicide: Theory and Evidence,” Aggression and Violent Behavior 8 (2003): 413–432.

- “En quinna war widh tolosa stadh swa som iak hørdhe aff hænna scriptafadhur hulkin som wan war badhe j genwerdho oc sælikhet at sighia aue maria Thæsse quinnan hafdhe skøran man ok for thy at hon wiste han synda met androm quinnom kom hon j swa mykin harm at hon thænkte at dræpa sik siælwa aff diæfwlsens inskiutilsom ok vm en hælghan dagh tha folkit war alt til mæsso wilde hon fulkomna sin onda tanka ok bleff hema fran mæssonne ok j førdhe sik ok thyngde sik met them thungasta klædhum ok skinnom som hon hafdhe ok kastadhe sik j ena floodh som ther war nær widhirfrestande met alle makt. at nidhirsænkia sik ok for matte ey vtan stodh owir watnit til thæs mæn komo ok vtleddo hona aff watnino. ok swa wardh hon fræls thy at hon ey afflæt at helsa guz modhor mar-iam.” KB Cod. A 110, fol. 89v–81r.

- Melancholy, which could lead to sorrow, apathy and loss of will to live, was considered by medieval authors to be one of the most typical forms of mental disorder; on concepts and expressions of melancholy, see the chapters of McCleery and Joutsivuo.

- KB Cod. A 110, fol. 72v, 73v–74r.

Contribution (75-90) from Mental (Dis)Order in Later Medieval Europe, edited by Sari Katajala-Peltomaa and Susanna Niiranen (Brill Academic Pub., 03.12.2014), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.