Illustrated scene from the Aeneid, a fantastic work of propaganda by Vergil to exalt the Roman Empire and Augustus / Wikimedia Commons

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Historian

Brewminate Editor-in-Chief

“The medium,” wrote Marshall McLuhan in 1964 in Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, “is the message.” Thus was laid a new foundation for the study of communication theory that had until then focused on the characteristics of only two groups of participants in the transmission process. The impression a sender wished to create among his receivers had been considered independent of and unaffected by the means in which he chose to do so. Jacques Ellul, a 20th century French law professor and philosopher at the University of Bordeaux, defined four categories of propaganda, each category containing a contradictory pair. These categories to some extent provide insight into the masterful manner in which Augustus manipulated the leaders and citizens of the Roman Republic. The methodologies he employed for himself and those used by others on his behalf would combine as past whispers of truth behind the phrase McLuhan coined nearly two millennia later. Within the generally accepted scholastic context of propaganda as that which attempts to influence peoples’ thinking (Galinsky, 40), and turning particularly to Ellul’s first two pairs of categories of propaganda – political vs. social and agitative vs. integrative – (Ellul, 62-84), a framework emerges in which to view Augustus’s rise to power and subsequent apotheosis.

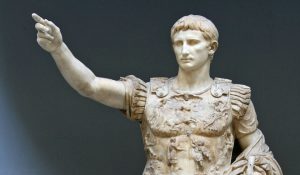

Augustus of Prima Porta, “So may I attain the honors of my father” / Wikimedia Commons

The political and social environment in which Augustus emerged was one of violence and discontent, more of which would be fostered in his efforts to establish a Roman golden age – Pax Romana. Citizens were teased with the appearance of stability, following a turbulent period of generals vying for power, when Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon and emerged victorious over Pompey. But it was short-lived with Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE, and Augustus (Octavian, adopted heir of Caesar) would find himself faced with the daunting task of restoring a Republic with a wounded cultural identity. (Zanker, 2) He would have to establish himself as both the rightful successor of Caesar as well as qualified and able to take on the leadership role that lay ahead. But he would have to accomplish it by maintaining the appearance of continuing a republican form of government as opposed to establishing a kingship. Cicero related his words from a speech by Augustus before the Senate near the end of 44 BCE in which he dramatically pointed to a statue of Caesar and said, “So may I attain the honors of my father.” (Cicero) A single motion and a few words symbolized his early mastery of propaganda in this political context. He would for the time being govern, merely as Octavian, in a triumvirate with Lepidus and Mark Antony following their alliance in the defeat of Caesar’s assassins, but attaining the honors of his father clearly indicated pursuit of singular reign and eventual divination himself after attributing the appearance of a comet to be a sign of Caesar’s apotheosis. (Ramsey and Licht, 4) Lepidus would pose no threat in this process, but Antony’s ambition would have to be addressed. In a war-weary society, unquestionable justification would be necessary to launch a military endeavor, and Antony would not disappoint.

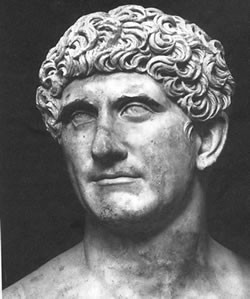

Busts of Antony (left) and Cleopatra (right) / Wikimedia Commons

Antony met Cleopatra in 41 BCE as he was en route to the Parthian campaign while Fulvia and his brother Lucius were struggling in his stead to maintain his status in Italy against an increasingly powerful Octavian. He openly stayed with her the Egyptian queen in Alexandria, enraging Fulvia with jealousy at home. Plutarch wrote of him being in Alexandria:

…there to keep holiday, like a boy, in play and diversion, squandering and fooling away in enjoyments that most costly, as Antiphon says, of all valuables, time. (Plutarch 182)

Romans were people who thrived on visual culture with lavish banquets and the wealthy with decors designed to impress guests – a culture that would in years following Augustus become even more indulgent. However, Antony had developed a reputation of being overly indulgent even by Roman standards. Described by Plutarch as “…at last rousing himself from sleep, and shaking off the fumes of wine…” (Plutarch 183) upon receiving messages that his wife and brother had fled Rome after failing to maintain his interests there and of the Parthians gaining ground, he set out to continue his campaign against them. He again abandoned that campaign and turned toward Rome while Fulvia, en route to meet him, fell ill and died in Sicyon. Upon his arrival in Rome, tensions with Octavian were settled by the Brundisium Agreement and the marriage of Antony to Octavia (Octavian’s elder sister) by Senate decree. The republic, as it still tried to operate, was divided between the two men – Octavian to govern in the West and Antony in the East. (McManus) In July 32 BCE, Octavian was informed by one of Antony’s most trusted confidants that in his will he bequeathed to the twins he had with Cleopatra all of his property as well as his portion of the republic in the East. It also included instructions that his body should be sent to Alexandria and buried there with her. This was a gift falling into Octavian’s lap, which he used to feed growing public resentment against Antony (Smith 291) and climb a pedestal of moral virtue.

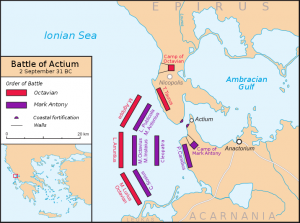

Battle of Actium (left) and Caesar and Augustus Sestertius (right) / Wikimedia Commons

Antony divorced Octavia via a messenger to Rome and ordered her to leave his house (with the children the two had to together as well as the children he had with Fulvia, who Octavia continued to care for), and with the “Donations of Alexandria” made public that which Octavian had already known – giving many Eastern territories to Cleopatra and declaring his son with her to be Caesar’s legal heir. (McManus) With public sentiment now heavily aligned against Antony, he became “persona non grata” in Rome, and the Senate declared war on Cleopatra. As disgust with Antony had circulated among citizens to a fever pitch, Octavian could put into play a propaganda of agitation to feed off of this outrage. He could rid himself of the last obstacle between himself and succession to Caesar with complete political and social support. Antony’s campaigns against the Parthians gained little ground and lost many troops, and Octavian could further establish himself as militarily superior by defeating Antony and reclaiming the Eastern territories. The Battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E. accomplished this task with Octavian’s fleet, commanded by his closest friend Agrippa. Cleopatra called her forces to retreat, and Antony could not present sufficient defense without them. The consequential suicides of Antony and Cleopatra eliminated the last vestiges of resistance to Octavian’s imperial ambitions. He would lay claim to saving not a single Roman life but instead the entire Roman Republic, leading the Senate in 27 BCE to endow him with the corona civica and confer upon him the title Caesar Augustus. (Augustus 399-401) Octavian, now Augustus Princeps (“the first of citizens”) after declining the title of imperator, had relinquished his potestas (official power) for a much more elastic social power – auctoritas – (Galinsky 3) that defied definition and placed in his hands complete power in Rome as the ultimate moral authority and allowed him to rule tacitly as a king while maintaining the outward illusion of a restored and continuing republic under the principate. Relinquishing certain titles and only (outwardly) reluctantly accepting others, as well as monuments that would be dedicated to him, Augustus put into play that false modesty which served the purpose of insuring more. (Deutsch, 142) To this point, Augustus had been able to use the actions of Antony as the basis of his propaganda. Coins had been created with his image, such as a sestertius around 40 BCE with the image of Julius Caesar on the obverse as the “divine Julius” and Octavian on the reverse as “son of the deified Julius.”

Mausoleum of Augustus, Campus Martius / Wikimedia Commons

Coins were a means of mass communication, used to instill a collective mentalité. Julius Caesar’s image was on them during his time, Augustus during his, and so on. Images of Augustus’s grandsons continued to appear on coins even after their deaths. Coins were also used to more effectively serve as mechanisms of support for that which already existed. (Galinsky 39). Not only did they influence thinking and effect circumstantial change, they also readily reflected existing thought and circumstances and provided validation. Getting out of Antony every drop of propaganda the experience offered, Augustus had a mausoleum built on the Campus Martius in Rome in 28 BCE. It had been three years since Antony’s suicide, and this would cause public resentment against him to resurface and once again confirm the confidence that had been expressed in the titles and power given to the clearly patriotic Augustus. The Res Gestae bronze inscription originally placed on the mausoleum provided a clear implication of Augustus’s apotheosis. (Elsner, 38-39) His body may lie in the tomb, but he would be elevated in death as he was in life. Monuments, art, and even literature provided permanent mediums through which Augustus could disseminate his image and message along with numismatic confirmation. Inscriptions on monuments or works such as the Res Gestae were equally as enduring as structures erected of concrete and marble.

The defeat of Antony and Cleopatra undoubtedly brought again to Romans the hope of peace and undisturbed prosperity. Augustus would need some reason to continue to legitimze his auctoritas and delay, temporarily of course – as he wished to be thought, completely relinquishing the republic back to the people. Who, after all, was left to present a threat from which it needed to be saved? He discovered the answer in the mirror. In 1948, Walt Kelly created a comic strip entitled “Pogo.” The opossum character coined in the 20th century a phrase that best sums up the answer Augustus sought two millennia earlier in the first century BCE: “We have met the enemy, and he is us.” Augustus held in his hands the reins to guide Rome’s morality. The momentary absence of a viable external threat allowed him to focus his attention on the enemy within. People would be blamed for bringing their troubles upon themselves by neglecting their religious allegiances to the gods and engaging in overly indulgent and immoral lifestyles. Augustus was brilliantly positioned as their intermediary to divine atonement. In 23 BCE, Horace supported this notion when he wrote on moral decadence, “Neglected gods have made many woes for you sad Italy.” (Horace 3.6) The people were not held out to have failed Augustus, the Senate, or any mortal, but the gods themselves! The message was driven consistently and deeply that the immorality which had crept into the empire had undermined the family, its foundation. Such literature was written within a social context Augustus was creating – one of reproductive responsibility ultimately in the name of loyalty to the republic.

Social propaganda is most effective on a nearly subliminal level in a work of art, literature, or any other disguise. “Art works,” wrote Ovid, “when it is hidden.” (Ovid 2.8) In spite of the longevity of the written word hailed by Horace and the literary output of Vergil, Ovid, and others, literacy in the Roman world prevented it from serving as a source of widespread propaganda. Notwithstanding the high rate of illiteracy caused by views of education in the ancient world and its staggered availability, continuing acquisition of new principalities presented both cultural and linguistic complications. (Harris, 331) A society’s organization (including and perhaps most importantly its hierarchical structure) and collective ethics determined the importance it placed on scholarship. Literature played a vital role in how people formed their religious beliefs and perspectives. (Humphrey, 198) A culture of visualization provided an environment in which such literature would accomplish its task much better by somehow provoking imagery in the reader’s mind. In the Aeneid, Vergil used a literary tool that succinctly frames the connection between visual art and the written word – ekphrasis. The impact the temple wall imagery had on Aeneas would have been perfectly understood by Romans. Vergil here emphasized the difference between the effect of sound (hearing a story performed) and of sight (the force of imagery on both heroine and reader). (Elsner, 89) Within this visual culture, the laws Augustus set upon enacting as Rome’s pater patriae and his divine status could be equally understood in Rome, Gaul and Greece. His agenda for Rome would only be successful if assimilated at all levels of society. Such assimilation is the root of integrative propaganda.

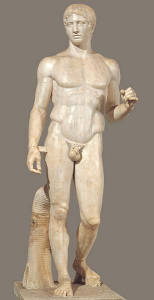

Augustus of Prima Porta c.20 BCE (left), Doryphoros by Polykleitos c.450-440 BCE (center), Aulus Metellus c.100 BCE (right) / Wikimedia Commons

With limited literacy and audible narrations lacking the impact of imagery as well as the immobility of monuments and structures, how was Augustus to accomplish such visual integration? Larger structures would prove to serve this purpose of course locally to those who could directly see them, but also in the much smaller collectibles they inspired containing the same messages that could be transmitted to every corner of the empire – along with coins. Around 20 BCE, the Senate commissioned and dedicated to Augustus the Prima Porta statue, and in 13 BCE the Ara Pacis Augustae. The Prima Porta celebrated his victories in Hispaniola and Gaul and contained imagery that nearly deified him in life. The stance recalls the Doryphorus of Polykleitos, and the orator’s gesture of the Aulus Metellus.

Gemma Augustea – two-layered onyx in gold frame, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (left) / Boscoreale Cup, Wikimedia Commons (right)

Perhaps the use of traditional representations influenced those of Augustus given his emphasis on tradition and morality. The Ara Pacis (featured image) remains one of, arguably the, most famous remnants of Augustan Rome. Every function Augustus served was displayed on the altar – Augustus as ruler, as imperial family head, and as pontifex maximus. Family and children displayed on the monument were clear indicators of August’s intent that there be an heir to his “throne.” The monument signifies the successful efforts of Augustus to bring the Pax Romana, which the people believed in truth to be the Pax Augusta. Pendants such as the Gemma Augustea and items such as the Boscoreale cups provided a mechanism through which this imagery could be widely dispersed and serve as points of discussion.

Monuments told stories, recounted victories, and hailed accomplishments. They influenced the thoughts of those who viewed them, or attempted to do so. These monuments reinforced Augustus’s legitimacy and praised the new golden age he was deemed to have brought to Rome, and he likewise reinforced the messages of the monuments by taking public actions. He boasted in the Res Gestae (Augustus, 133) of having closed the Gates of Janus three times, more than any other in the history of Rome. The gates were open when Rome was at war and closed when at peace throughout the empire. He closed them in 29 BCE following the deaths of Antony and Cleopatra and then again in 25 BCE following provincial conquests. (Dio, 51.20 and 53.27) The third closing date is not accurately known. They would become a metaphorical tool by which he would claim responsibility for universal peace. (Thomas, 69) The propaganda of Augustus was not a linear effort but instead a system of one form being influenced by another and itself influencing yet another.

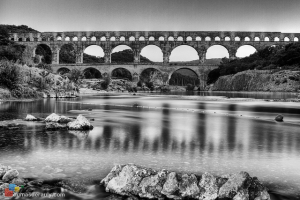

Pont-du-Gard Aqueduct in France / By Arnaud Dumas de Rauly, 2011

Augustus had risen to power with the full support of the Senate and the people, and he had thus far retained his auctoritas through continued conquest and finally ushering in an era of what they saw as peace. His legitimacy and even unspoken apotheosis were unquestioned. But the winds of change blew just as quickly and easily then as they do today. Maintaining control of anything is not a singularly accomplished task but is instead ongoing. The propaganda that had served him well would continue to be used to reinforce the continued auctoritas that would be endowed to his heirs as his dynasty – thus the Roman Empire – was born. In the Aeneid, emphasis was placed on the importance of the work that needed to be done. Instead of writing it from a backward-looking point of view with Aeneas already in his final position, Vergil focused on the work that lay ahead and the trials and tribulations Aeneas would have to face and overcome. Likewise, Ovid focused on Apollo’s pursuit of Daphne instead of the result. These stories encapsulated the importance and rewards not of reaching the republic’s glorious apex but rather in the effort to achieve it. The act of building the city and numerous works of infrastructure was in itself a propagandistic display of the elastic auctoritas Augustus possessed. He had monuments and structures erected not only in Rome proper but throughout the empire, keeping the necessity of the work to be done and the fruits it could bear in the minds of provincial subjects as well. Suetonius wrote that Augustus had good intentions but emphasized that it was not clear if the results reflected them. Augustus felt, he wrote, that “…it would be hazardous to trust the State to the control of more than one…” (Suetonius, 165) Infrastructure improvements such as the Pont-du-Gard and increased security from external threats had calculable value. They were rational supports for the power and titles Augustus held, and there was no dearth of propaganda – emotive appeals, symbols, etc. – to keep them in the minds of the people. The pinnacle of Rome continued to be just beyond reach, providing continuing justification not only for his continued rule but for those who would succeed him. Augustan propaganda recollected the past and his place in it, praised him for present conditions, and made it clear that they would only continue under his influence.

The future of Rome was seen as securely in the hands of a competent ruler. Never shown as older than when he pointed to a statue of his adoptive father before becoming Augustus, publicly hoping to take his place, he was of course known to be mortal and the people placed faith in him to leave a successor who would continue his work. There would be a reference to Augustus in every facet of society – construction, art, sculpture, literature, and more, even including private collectibles. His own work, the Res Gestae, though then simply an autobiography that would be seen as relating factual information about his reign, is today viewed as the rant of an egomaniac. After obvious enemies were disposed of, he would convince the people of their part in their own destruction. He saved them from the traitorous Antony and others who would stand as aggressors such as the Parthians, as attested on the Prima Porta cuirass. But, alas, to save them from themselves required unquestioned authority and obedience to moral legislation. He would humbly accept the challenges with which he was presented and demand no title. But retrospect allows reading between the lines and seeing behind every monument and in every work of art or literature the invisible message, “I am all.” He knew full well the visual culture in which he reigned, and he used it wisely to his advantage. Words supported images which in turn reinforced words. A person could be told of the accomplishments of Augustus, or they could stand in front of the Prima Porta statue. It takes no stretch of the imagination to know which would remain in that person’s memory. “I found Rome a city of brick,” Suetonius reports Augustus as saying, “and left her a city of marble.” (Suetonius, 167) This is what Augusrtus wished people, literally and figuratively, to see. Combining the proverbial picture with its thousand words, he instinctively knew then the truth behind what would be McLuhan’s modern advice that the method used to convey a message actually is the message.

REFERENCES

Augustus (Imperator Gaius Julius Caesar Augusts, Born Gaius Octavius Thurinus). Res Gestae Divi Augusti. Trans. Frederick W. Shipley. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1924.

Cicero, Marcus Tullius. “Epistulae ad Atticum, 16.15.3.” May 24-June 2, 44 B.C.E. On Latin Texts and Translations, Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University.

Deutsch, Helen. Resemblance & Disgrace: Alexander Pope and the Deformation of Culture. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1996.

Dio, Cassius (Lucius Cassius Dio Cocceianus). History of Rome, Vol. VI. Amazon Digital Services, Public Domain Books, 2004.

Ellul, Jacques. Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes. New York: Vintage, 1973.

Elsner, Jaś. Art and Text in Roman Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1996.

Galinsky, Karl. Augustan Culture: An Interpretive Introduction. New Jersey: Princeton UP, 1998.

Harris, William V. Ancient Literacy. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1991.

Horace (Flaccus, Quintus Horatius). The Odes. Trans. A.S. Kline.

Humphrey, J.H. “Literacy in the Roman World.” Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 3. Portsmouth, 2007.

Lamp, Kathleen. “The Ara Pacis Augustae: Visual Rhetoric in Augustus’ Principate.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 39, 2009.

McCoy, Marsha B. “Poetry and Propaganda: Vergil’s Aeneid and the Temple of Mars Ultor in the Forum Augustum.” Vergilian Society Panel. Renaissance Hotel, Oklahoma City, OK. 27 March 2010.

McManus, Barbara F. “Antony, Octavian, Cleopatra: The End of the Republic.” The College of New Rochelle. VRoma, August 2009.

Ovid (Naso, Publius Ovidius). Ovid: The Art of Love (Ars Armatoria). Trans. A.S. Kline, 2001.

Plutarch (Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus). Plutarch’s Lives. Trans. John Dryden. Ed. Arthur H. Clough. Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1859.

Ramsey, John, and A. Lewis Licht. The Comet of 44 B.C. and Caesar’s Funeral Games, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Shotter, David. Augustus Caesar. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Smith, Philip. A History of the World: From the Earliest Records to the Present Time. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1866.

Suetonius (Tranquilius, Gaius Suetonius). The Lives of the Twelve Caesars: Vol 1, The Life of Augustus. New York: Loeb Classical Library, 1914.

Thomas, Richard F. Virgil and the Augustan Reception. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004.

Zanker, Paul. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. Trans. Alan Shapiro. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1988.