The history of autism is not the story of a timeless condition waiting to be discovered, but rather a history of interpretation.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Autism, today categorized within the diagnostic rubric of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), is not a condition newly discovered by modern medicine but rather a phenomenon whose manifestations can be traced across cultures and epochs. What is new is the vocabulary and conceptual framing through which societies have attempted to make sense of difference. From antiquity onward, individuals who spoke little, avoided eye contact, or displayed unusual fixations have been alternately treated as divinely inspired, morally suspect, intellectually deficient, or medically abnormal. Each epoch (ancient, medieval, early modern, and contemporary) has inscribed its own cultural anxieties onto those whose behaviors departed from prevailing norms.

The historiography of autism is necessarily complicated by the methodological problem of retrospective diagnosis. One cannot with certainty declare that a silent child in Galen’s case notes or a visionary recluse in a medieval monastery was “autistic” in the modern sense. Scholars caution against what Ian Hacking has called the “looping effect” of human kinds: the way classifications reshape the people they describe, altering both present identities and historical readings of the past.1 To write a history of autism, therefore, is less to identify an unbroken chain of clinical cases than to examine how societies have understood, pathologized, or at times sanctified behaviors that today fall under the autistic spectrum.

This inquiry matters not only for the sake of intellectual completeness but also for its political and ethical implications. Misinterpretations such as Bruno Bettelheim’s infamous “refrigerator mother” theory in the mid-20th century had devastating consequences for families.2 Conversely, the rise of the neurodiversity movement at the turn of the 21st century represents an effort to reclaim dignity, framing autism not as a deficit but as a natural variation of human cognition.3 Placing the history of autism within a longue durée, from antiquity’s “holy fools” to modern diagnostic manuals, enables us to see the ways in which medical, religious, and cultural systems have shaped both the stigma and the recognition attached to autistic lives.

Antiquity: Early Descriptions of Difference

The ancient world did not possess a category resembling “autism,” yet scattered references across Greco-Roman literature suggest that certain behaviors now associated with the spectrum were observed, if not clinically defined. Hippocrates, for example, linked unusual silence and withdrawal to imbalances of the humors, particularly black bile, which produced what he termed melancholia, a state marked by sadness, inwardness, and aversion to social interaction.4 While such descriptions may reflect depression rather than autism in the modern sense, they reveal how silence and detachment were pathologized within the prevailing medical framework.

Philosophers and rhetoricians likewise described forms of difference that resonate with contemporary accounts of autistic traits. Cicero, for instance, contrasts the eloquent orator with those who are “tongue-tied” or unable to follow the rhythms of discourse, a mark of deficiency in a society that equated civic participation with verbal fluency.5 In a culture where public speech was the measure of citizenship, atypical communicative styles could brand one as deviant, even dangerous to the fabric of civic life. Roman legal discourse sometimes invoked the category of the furiosus, those incapable of rational deliberation, as grounds for diminished responsibility or exclusion from civic duties.6

Religious interpretations also played a role in framing behaviors outside the norm. The Greeks and Romans often attributed unusual fixations or social withdrawal to divine possession or inspiration, suggesting that those who appeared “mad” might in fact be touched by the gods.7 This ambiguity, between pathology and sanctity, laid the groundwork for later medieval notions of the “holy fool,” who confounded worldly wisdom through eccentric or socially disruptive behavior.

The problem for historians is not whether these individuals “had autism,” but how their societies interpreted their difference. Ancient case notes and rhetorical texts testify to a world that recognized and classified forms of otherness, even as the language and logic used diverged radically from modern clinical categories. The ancient world thus provides less a set of proto-diagnoses than a mirror for examining how human cultures have always grappled with the enigma of cognitive and behavioral variation.

Medieval and Early Modern Perspectives

With the collapse of the Roman Empire and the rise of Christianity in Europe, interpretations of behavioral difference shifted from humoral imbalance to moral and spiritual paradigms. Silence, withdrawal, or repetitive gestures were no longer primarily understood as symptoms of disordered bodies but as signs of spiritual states. A child who avoided speech or eye contact might be thought bewitched, possessed, or alternatively touched by divine grace. Monastic hagiographies occasionally describe figures whose eccentricities set them apart from ordinary life. Saints who refused social contact, engaged in obsessive prayer, or displayed striking indifference to worldly affairs were sometimes revered as vessels of holiness rather than pathologized as ill.8

At the same time, medical traditions rooted in Galen and Arabic scholars such as Avicenna retained explanatory power. Medieval physicians often drew on humoral theory to interpret persistent mutism or strange fixations, prescribing dietary changes, bloodletting, or herbal remedies.9 While these approaches rarely distinguished among conditions we would today separate into autism, epilepsy, or intellectual disability, they reinforced the view that atypicality was a condition requiring intervention.

The institutional response to such difference emerged in part through the Church. Monasteries and charitable hospitals often cared for those considered “innocents” or “natural fools,” categories encompassing both the intellectually disabled and those whose behaviors simply seemed alien.10 These individuals occupied an uneasy space: pitied as childlike, sometimes tolerated within religious life, yet also vulnerable to exploitation or neglect.

By the early modern period, with the rise of Protestant reform and the beginnings of secular states, the interpretive frameworks shifted once more. Eccentricity became a more pronounced category, and the line between inspired oddity and dangerous deviance narrowed. Witchcraft trials of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries occasionally targeted individuals whose strangeness (aloofness, monotone speech, or peculiar ritual behaviors) was construed as evidence of demonic pacts.11 At the same time, humanist writers such as Erasmus distinguished folly that entertained or instructed from folly that signaled incapacity.12 These shifting evaluations reflected a Europe wrestling with both the residual authority of religion and the emerging authority of rationalist explanation.

By the seventeenth century, then, the stage was set for a decisive transformation: the emergence of medicine and philosophy as competing forces in defining human difference. No longer confined to theological or humoral categories, behaviors associated with autism would soon be pulled into the orbit of early psychiatry, where they were subjected to new forms of classification, measurement, and often, confinement.

The Enlightenment and the Rise of Medical Rationalism

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries marked a decisive shift in the treatment of atypical minds. While religious categories remained influential, Enlightenment rationalism increasingly framed difference in terms of reason, will, and natural law. The intellectual atmosphere of the period – emphasizing classification, taxonomy, and the universality of human faculties – invited renewed scrutiny of those who failed to conform to emerging standards of rational subjecthood.

John Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) posed a critical philosophical question: what distinguished those capable of forming ideas and participating in rational discourse from those who could not?13 Locke, like Descartes before him, distinguished between the rational mind and its aberrations, situating certain individuals beyond the bounds of “civil” humanity. In doing so, he gave philosophical grounding to older assumptions that those who were mute, withdrawn, or unable to manage abstract concepts were fundamentally impaired in their moral and civic capacities.

Medical practice followed suit. Physicians such as Thomas Willis in England and later Philippe Pinel in France described cases of “idiocy” and “imbecility” with an eye toward systematic classification.14 These categories, while blunt and often cruel, reflect the Enlightenment drive to impose order on the diversity of human experience. What had once been described in moral or spiritual terms was increasingly framed as deviation from the “normal” operations of reason.

Institutional responses reflected this new rationalist ethos. The proliferation of asylums across Europe and colonial America signaled both humanitarian intent and coercive control. Reformers like Pinel advocated for traitement moral, a regimen of structured routine, surveillance, and limited freedoms designed to restore rational order to disordered minds.15 Yet this model simultaneously excluded those who did not respond to training, particularly children whose silence or repetitive behaviors were judged beyond reform. Instead of being tolerated within religious life as “innocents,” they were increasingly sequestered from society as failures of reason.

The Enlightenment thus deepened the paradox of human difference. On the one hand, its commitment to universality suggested that all people shared basic faculties of reason and could, in principle, be educated. On the other hand, its obsession with order and productivity cast those who resisted normative frameworks as defective, unfit, or burdensome. Children who today might be recognized as autistic were not yet a medical category, but they were increasingly swept into institutional life as exemplars of failed rationality. The groundwork was laid for the nineteenth century’s more elaborate attempts to differentiate, classify, and rehabilitate such children within the emerging disciplines of psychiatry and pedagogy.

The 19th Century: Psychiatry, Education, and the “Othered” Child

The nineteenth century witnessed the formal birth of psychiatry as a discipline, and with it the more systematic categorization of behaviors that would one day be folded into the autism spectrum. In this era, the ambiguous categories of idiocy and imbecility were codified, measured, and institutionalized under the auspices of medical science. Physicians such as Philippe Pinel’s student Jean-Étienne Esquirol developed increasingly precise distinctions, identifying idiocy as a congenital inability to develop rational faculties and dementia as their subsequent decline.16 By parsing these categories, psychiatrists sought to impose taxonomic order upon the wide variety of children and adults whose differences resisted easy explanation.

Institutions for the “feebleminded” grew rapidly across Europe and the United States. In these settings, children who spoke little, repeated phrases, or showed obsessive fixations were grouped with the intellectually disabled.17 While few observers explicitly identified autism-like behaviors as distinct, institutional records describe individuals marked by social withdrawal, echolalia, or intense preoccupation with specific objects, features that resonate with contemporary diagnostic frameworks. Yet such children were rarely seen as individuals with unique cognitive profiles; rather, they were absorbed into a broader class of those who represented the failure of modernity’s educational and social ideals.

Educational reformers nonetheless began to challenge this assumption. The French physician Jean-Marc-Gaspard Itard became famous for his work with Victor, the so-called “wild boy of Aveyron,” discovered in 1799.18 Though Victor’s condition was not autism in the modern sense, Itard’s experiments with sensory training and structured pedagogy suggested that even children once deemed uneducable might benefit from systematic intervention. His student Édouard Séguin extended these methods, founding specialized schools that emphasized motor and sensory exercises.19 For the first time, educators began to treat developmental difference not simply as a deficit but as a challenge to be addressed through individualized instruction.

Yet even this optimism carried a darker undertone. As industrial capitalism matured, societies demanded conformity to norms of labor, discipline, and productivity. Children who could not assimilate to classroom routines or factory rhythms became visible precisely as failures of social order.20 The “normal child” emerged as a statistical and cultural category, against which difference was sharply defined. In this context, children who today might be recognized as autistic were increasingly seen as burdens: objects of study, intervention, or confinement, but seldom subjects with voices of their own.

By the end of the century, psychiatry and pedagogy had laid the groundwork for modern concepts of developmental disorder. Yet autism remained unnamed, subsumed within broader labels of deficiency. The nineteenth century’s legacy was thus double-edged: it created the infrastructure of institutions and educational experiments that would eventually enable recognition, while also entrenching practices of exclusion that would haunt autistic individuals well into the twentieth century.

The 20th Century: From Kanner and Asperger to the DSM

The twentieth century brought the first explicit recognition of autism as a distinct medical category, though the road to that recognition was shaped by the century’s darker currents of eugenics, institutionalization, and shifting psychiatric theory. At the dawn of the century, children who exhibited the traits we now associate with autism (limited speech, repetitive behaviors, difficulty with social reciprocity) were still diagnosed under broader labels such as “childhood schizophrenia” or “mental defect.”21 In the climate of eugenics that pervaded Europe and the United States, such children were often institutionalized, sterilized, or excluded from public life.22

The term autism itself was first introduced by the Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler in 1911, within his classic work on schizophrenia.23 For Bleuler, autismus described the withdrawal of patients into inner fantasy worlds, marked by detachment from social reality. He considered it a symptom of schizophrenia rather than a distinct condition, but the concept would prove foundational. By highlighting social withdrawal and idiosyncratic cognition as central to psychiatric nosology, Bleuler inadvertently created the conceptual space later occupied by childhood autism. His use of the term thus represents the hinge between older frameworks of “insanity” and the eventual recognition of autism as a separate developmental disorder.

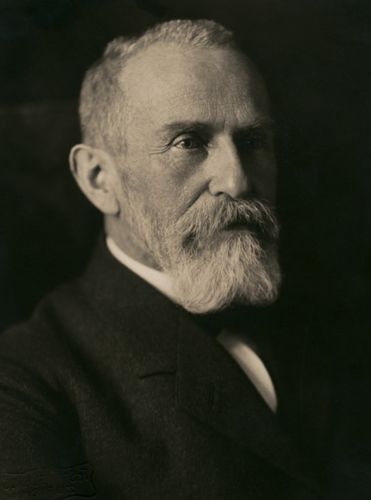

The pivotal breakthrough came in the 1940s, during the upheaval of the Second World War. In 1943, Austrian-born psychiatrist Leo Kanner, working at Johns Hopkins University, published a landmark paper describing eleven children with what he termed “early infantile autism.”24 Kanner emphasized their profound social detachment, obsessive desire for sameness, and precocious but unusual use of language. Importantly, he distinguished this syndrome from childhood schizophrenia, arguing that it represented a congenital condition present from the earliest months of life. One year later, across the Atlantic, Hans Asperger published his study of “autistic psychopathy” in Vienna.25 His patients, mostly boys, displayed fluent but idiosyncratic speech, narrow fixations, and striking difficulties with social integration. Though Asperger’s work remained little known in the Anglophone world until the 1980s, it foreshadowed later debates over the “spectrum” nature of autism.

The wartime context of these discoveries is critical. Asperger’s clinic operated under the shadow of Nazi racial hygiene policies, which targeted disabled children for euthanasia.26 While Asperger may have attempted to protect some of his patients by emphasizing their usefulness to society, others were not spared. The history of autism’s “discovery” is thus inseparable from the violence inflicted upon those whose differences made them vulnerable to state persecution.

In the postwar decades, autism was gradually integrated into the emerging psychiatric nosology. Yet its status remained ambiguous. Many clinicians continued to classify it as a form of childhood schizophrenia well into the 1960s, reflecting psychoanalytic dominance in psychiatry.27 Bruno Bettelheim’s theory of the “refrigerator mother,” which cast autism as the product of cold and unaffectionate parenting, exemplified the disastrous consequences of this psychoanalytic framework.28 Families, especially mothers, were blamed for their children’s condition, a burden of guilt that compounded the challenges of raising autistic children and delayed the development of effective support systems.

By the latter half of the century, however, the psychiatric consensus shifted. The publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980 recognized autism as a distinct diagnostic category for the first time.29 Subsequent revisions, culminating in the DSM-IV (1994), broadened the spectrum to include Asperger’s Disorder and Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), reflecting the growing recognition that autism encompassed a wide range of presentations.30 This period also witnessed the emergence of early epidemiological studies, which began to document the prevalence of autism more systematically, though often with inconsistent methods and contested results.

The twentieth century thus marked a profound turning point: autism moved from an unnamed condition hidden within the walls of asylums to a recognized clinical diagnosis enshrined in psychiatric manuals. Yet this recognition was accompanied by stigma, misinterpretation, and trauma, as autistic individuals and their families navigated a medical system still struggling to reconcile scientific description with humane understanding. The groundwork was laid for the explosive debates of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, when advocacy, science, and culture would collide to redefine what it meant to live as an autistic person.

Late 20th Century: Expansion, Advocacy, and Controversy

By the late twentieth century, autism had become a recognized psychiatric diagnosis, yet its boundaries remained contested and its social meanings deeply fraught. The codification of autism in the DSM-III (1980) marked an official break from schizophrenia, but this very act of definition sparked debates about who counted as autistic and how the condition should be understood. The DSM-IV in 1994 expanded the classification further, introducing subtypes such as Asperger’s Disorder and PDD-NOS.31 This expansion led to a dramatic rise in reported prevalence, prompting both hope that more individuals would receive services and fears of an “autism epidemic” that remains a point of public confusion.

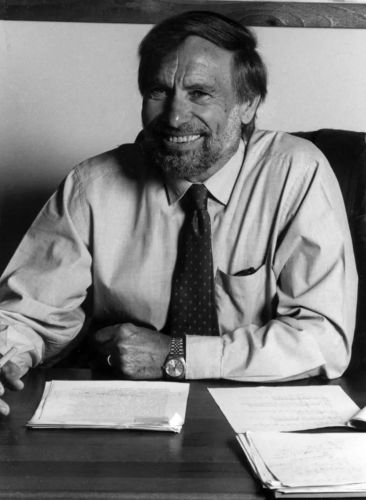

Alongside these shifting diagnostic categories, a vibrant field of autism research took shape. Behavioral psychology offered one of the most prominent, if controversial, approaches. Ivar Lovaas pioneered Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), claiming that rigorous behavioral interventions could “normalize” autistic children.32 While some families celebrated the progress their children made through such programs, autistic self-advocates later criticized ABA as coercive, prioritizing conformity over dignity.33 Other researchers explored genetic and neurological underpinnings, laying the foundation for today’s biomedical frameworks. These scientific advances, however, often collided with cultural anxieties about causation and responsibility.

Few controversies proved as damaging as the persistence of psychoanalytic theories into the 1960s and 1970s. Bruno Bettelheim’s “refrigerator mother” hypothesis lingered in popular discourse even after empirical evidence had refuted it, shaping public perceptions and placing undue blame on mothers.34 At the same time, the deinstitutionalization movement in the United States and Europe exposed the brutal conditions of state hospitals such as Willowbrook, sparking a broader reckoning with the treatment of disabled people.35 Families organized for better services, founding advocacy groups like the Autism Society of America (1965), which pushed for educational rights and public recognition.

Popular culture also began to play a significant role in shaping autism’s image. The 1988 film Rain Man, featuring Dustin Hoffman as an autistic savant, brought autism into mainstream consciousness but also narrowed public understanding to a stereotype of mathematical genius combined with social ineptitude.36 Such portrayals raised awareness but reinforced misconceptions, complicating advocacy efforts.

By the end of the twentieth century, autism had become both a clinical category and a social battleground. Families, professionals, and increasingly autistic individuals themselves contested its meaning. Was autism a tragic disability to be cured, a mysterious epidemic to be explained, or a lifelong identity to be embraced? These competing narratives set the stage for the twenty-first century’s turn toward neurodiversity, in which autistic voices began to reshape the conversation on their own terms.

The 21st Century: Neurodiversity and Global Awareness

The dawn of the twenty-first century transformed autism from a narrowly clinical category into a global social and political movement. Central to this transformation was the rise of the neurodiversity paradigm, first articulated in the late 1990s by autistic self-advocates such as Jim Sinclair, whose 1993 essay “Don’t Mourn for Us” challenged parents and professionals to see autism not as a tragedy but as a different way of being.37 This perspective gained momentum through the work of scholars like Judy Singer, who coined the term “neurodiversity” to describe the natural variation of human minds.38 What had long been framed in terms of deficit and disorder now began to be reimagined as a spectrum of cognitive diversity deserving respect and accommodation.

Institutionally, diagnostic frameworks continued to evolve. The DSM-5 (2013) collapsed the multiple subtypes of the DSM-IV into a single category, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD, in recognition of the continuum of traits and intensities.39 This shift generated both relief and anxiety: while it reflected scientific consensus about autism’s spectrum nature, it also threatened to exclude some individuals, especially those previously diagnosed with Asperger’s Disorder, from services. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), adopted by the World Health Organization in 2022, likewise embraced the spectrum model, cementing it as the dominant framework in global psychiatry.

Culturally, autistic voices became increasingly central. Online communities, social media platforms, and advocacy organizations such as the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN, founded 2006) amplified autistic perspectives, challenging paternalistic models of care.40 These voices critiqued applied behavior analysis and cure-oriented research while advocating instead for acceptance, accessibility, and systemic support. The rallying cry of “Nothing About Us Without Us” epitomized this shift from object to subject, from patient to activist.

Public awareness campaigns, however, often reflected competing visions. Organizations like Autism Speaks, founded in 2005, initially emphasized causation and cure, funding genetic research and promoting alarmist rhetoric about an “autism crisis.”41 In contrast, autistic-led groups pressed for resources to improve quality of life, highlighting employment discrimination, inadequate healthcare, and the lack of inclusive education. This clash revealed the fault lines between biomedical and social models of disability.

Globally, recognition of autism expanded beyond Western contexts. In countries such as India, China, and across Africa, advocacy efforts began to address cultural stigma, limited diagnostic resources, and the urgent need for educational accommodations.42 International frameworks, including the United Nations’ 2007 adoption of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, framed autism as a human rights issue, emphasizing inclusion and dignity.

By the 2020s, autism had thus become a nexus of scientific research, cultural debate, and political activism. The tension between pathology and identity, cure and acceptance, remains unresolved, yet the voices of autistic individuals themselves have become impossible to ignore. What began in antiquity as descriptions of aloofness or divine inspiration has culminated in a global conversation about difference, diversity, and the very definition of what it means to be human.

Conclusion

The history of autism is not the story of a timeless condition waiting to be discovered, but rather a history of interpretation. From antiquity’s physicians and philosophers, who explained silence and withdrawal through humors or divine possession, to medieval monks who alternately revered and feared eccentricity, to Enlightenment rationalists who measured deviation as a failure of reason, each era inscribed its own anxieties upon those whose behaviors fell outside expected norms. The nineteenth century’s taxonomies, the twentieth century’s diagnoses, and the twenty-first century’s neurodiversity movement all reveal less about autism as a fixed entity than about the shifting cultural landscapes in which it has been understood.

At the same time, there is a through-line that cannot be ignored: the persistence of human difference, appearing across time in ways that compel recognition. Whether pathologized, institutionalized, or celebrated, individuals whose behaviors resonate with what we now call autism have always existed. Their treatment, whether cruel exclusion or cautious acceptance, illuminates the values and limitations of the societies around them. In this sense, autism’s history is also a mirror of humanity’s struggle to define normality, rationality, and belonging.

The contemporary embrace of neurodiversity represents both a rupture with and a continuation of this past. It rejects centuries of stigma and coercion, affirming instead that autistic lives are not broken versions of humanity but vital expressions of its diversity. Yet it also participates in a much older pattern: the effort to give meaning, dignity, and explanation to behaviors that resist conformity. To study the history of autism, then, is to confront the uneasy boundary between medical science and cultural judgment, between pathology and identity. It is to see in the past both the wounds inflicted by misunderstanding and the enduring possibilities of recognition.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Ian Hacking, The Social Construction of What? (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 103–106.

- Bruno Bettelheim, The Empty Fortress: Infantile Autism and the Birth of the Self (New York: Free Press, 1972).

- Steve Silberman, NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity (New York: Avery, 2015).

- Hippocrates, Aphorisms, trans. W.H.S. Jones (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931), 132.

- Cicero, De Oratore, trans. E.W. Sutton (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1942), 2.45.

- Justinian, Digest of Roman Law, trans. Alan Watson (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985), 1.18.14.

- Plutarch, Moralia, trans. Frank Cole Babbitt (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1927), 219.

- The Life of St. Symeon the Fool, trans. Derek Krueger (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996).

- Avicenna, The Canon of Medicine, trans. Laleh Bakhtiar (Chicago: Great Books of the Islamic World, 1999), 456.

- P. Horden, “A Discipline of Relevance: The Historiography of the Later Medieval Hospital,” Social History of Medicine 1, no. 3 (1988): 359–374.

- Brian Levack, The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe (London: Longman, 1987), 134–136.

- Desiderius Erasmus, The Praise of Folly, trans. Clarence H. Miller (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 56–57.

- John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, ed. Peter Nidditch (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), II.xi.

- Thomas Willis, Two Discourses Concerning the Soul of Brutes (London: 1683), 41–42; Philippe Pinel, Traité médico-philosophique sur l’aliénation mentale (Paris: 1801).

- Dora Weiner, The Citizen-Patient in Revolutionary and Imperial Paris (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993), 78–80.

- Jean-Étienne Esquirol, Mental Maladies: A Treatise on Insanity, trans. E.K. Hunt (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1845), 45–47.

- David Wright, Mental Disability in Victorian England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2001), 63–64.

- Jean-Marc-Gaspard Itard, The Wild Boy of Aveyron, trans. George and Muriel Humphrey (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1962).

- Édouard Séguin, Idiocy: And Its Treatment by the Physiological Method (New York: William Wood, 1866).

- Nikolas Rose, The Psychological Complex (London: Routledge, 1985), 112–115.

- Henry H. Goddard, The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeblemindedness (New York: Macmillan, 1912).

- Daniel J. Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985).

- Eugen Bleuler, Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias, trans. Joseph Zinkin (New York: International Universities Press, 1950 [1911]), 63–64.

- Leo Kanner, “Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact,” Nervous Child 2 (1943): 217–250.

- Hans Asperger, “Autistic Psychopathy in Childhood,” Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 117 (1944): 76–136.

- Edith Sheffer, Asperger’s Children: The Origins of Autism in Nazi Vienna (New York: W.W. Norton, 2018).

- Michael Rutter, Infantile Autism: Concepts, Characteristics, and Treatment (London: Churchill Livingstone, 1972).

- Bettelheim, Empty Fortress.

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. (Washington, D.C.: APA, 1980).

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (Washington, D.C.: APA, 1994).

- Ibid.

- O. Ivar Lovaas, “Behavioral Treatment and Normal Educational and Intellectual Functioning in Young Autistic Children,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 55, no. 1 (1987): 3–9.

- Ari Ne’eman, “When Autism Speaks, It’s Time to Listen,” Disability Studies Quarterly 30, no. 1 (2010).

- Bettelheim, Empty Fortress.

- Robert F. Kennedy, “Exposé of Willowbrook State School,” ABC News, January 1965.

- Barry Levinson, dir., Rain Man (United Artists, 1988).

- Jim Sinclair, “Don’t Mourn for Us,” Our Voice (Autism Network International), 1993.

- Judy Singer, “Why Can’t You Be Normal for Once in Your Life?” in Disability Discourse, ed. Mairian Corker and Sally French (Buckingham: Open University Press, 1999), 59–67.

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. (Washington, D.C.: APA, 2013).

- Autistic Self Advocacy Network, “About ASAN,” 2006, https://autisticadvocacy.org.

- Chloe Silverman, Understanding Autism: Parents, Doctors, and the History of a Disorder (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 182–186.

- Roy Richard Grinker, Unstrange Minds: Remapping the World of Autism (New York: Basic Books, 2007).

Bibliography

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd, 4th, and 5th eds. Washington, D.C.: APA, 1980–2013.

- Asperger, Hans. “Autistic Psychopathy in Childhood.” Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 117 (1944): 76–136.

- Autistic Self Advocacy Network. “About ASAN.” 2006.

- Avicenna. The Canon of Medicine. Translated by Laleh Bakhtiar. Chicago: Great Books of the Islamic World, 1999.

- Bettelheim, Bruno. The Empty Fortress: Infantile Autism and the Birth of the Self. New York: Free Press, 1972.

- Bleuler, Eugen. Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias. Translated by Joseph Zinkin. New York: International Universities Press, 1950 [1911].

- Cicero. De Oratore. Translated by E.W. Sutton. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1942.

- Erasmus, Desiderius. The Praise of Folly. Translated by Clarence H. Miller. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979.

- Esquirol, Jean-Étienne. Mental Maladies: A Treatise on Insanity. Translated by E.K. Hunt. Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1845.

- Goddard, Henry H. The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeblemindedness. New York: Macmillan, 1912.

- Grinker, Roy Richard. Unstrange Minds: Remapping the World of Autism. New York: Basic Books, 2007.

- Hacking, Ian. The Social Construction of What? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Hippocrates. Aphorisms. Translated by W.H.S. Jones. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931.

- Horden, P. “A Discipline of Relevance: The Historiography of the Later Medieval Hospital.” Social History of Medicine 1, no. 3 (1988): 359–374.

- Itard, Jean-Marc-Gaspard. The Wild Boy of Aveyron. Translated by George and Muriel Humphrey. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1962.

- Kanner, Leo. “Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact.” Nervous Child 2 (1943): 217–250.

- Kevles, Daniel J. In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Levack, Brian. The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe. London: Longman, 1987.

- Levinson, Barry, dir. Rain Man. United Artists, 1988.

- Locke, John. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Edited by Peter Nidditch. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975.

- Lovaas, O. Ivar. “Behavioral Treatment and Normal Educational and Intellectual Functioning in Young Autistic Children.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 55, no. 1 (1987): 3–9.

- Ne’eman, Ari. “The Future (and the Past) of Autism Advocacy, Or Why the ASA’s Magazine, The Advocate, Wouldn’t Publish This Piece.” Disability Studies Quarterly 30, no. 1 (2010).

- Pinel, Philippe. Traité médico-philosophique sur l’aliénation mentale. Paris, 1801.

- Plutarch. Moralia. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1927.

- Rose, Nikolas. The Psychological Complex. London: Routledge, 1985.

- Rutter, Michael. Infantile Autism: Concepts, Characteristics, and Treatment. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1972.

- Séguin, Édouard. Idiocy: And Its Treatment by the Physiological Method. New York: William Wood, 1866.

- Sheffer, Edith. Asperger’s Children: The Origins of Autism in Nazi Vienna. New York: W.W. Norton, 2018.

- Silberman, Steve. NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity. New York: Avery, 2015.

- Silverman, Chloe. Understanding Autism: Parents, Doctors, and the History of a Disorder. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Sinclair, Jim. “Don’t Mourn for Us.” Our Voice (Autism Network International), 1993.

- Singer, Judy. “Why Can’t You Be Normal for Once in Your Life?” In Disability Discourse, edited by Mairian Corker and Sally French, 59–67. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1999.

- Weiner, Dora. The Citizen-Patient in Revolutionary and Imperial Paris. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

- Willis, Thomas. Two Discourses Concerning the Soul of Brutes. London, 1683.

- Wright, David. Mental Disability in Victorian England. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2001.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.24.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.