The presence of troops in American streets no longer shocks. That may be the most lasting erosion of Posse Comitatus: not the breach, but the forgetfulness.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Troops, Territory, and the American Threshold

Since its passage in 1878, the Posse Comitatus Act has stood as a bulwark – fragile, often symbolic – between civilian life and federal militarization. The law, shaped in the aftermath of Reconstruction, restricts the use of the Army (and later the Air Force) for domestic law enforcement, reflecting a deep American suspicion of standing armies in public life. Yet this prohibition has always been porous, contested not just in the courts but in moments of political rupture. The Act does not prohibit military involvement entirely. It prohibits direct enforcement of domestic law unless expressly authorized by the Constitution or an act of Congress. That distinction, simultaneously precise and evasive, has offered presidents a narrow legal corridor, and, at times, a wide political stage.

Over the course of the twentieth century, several presidents invoked federal military power in ways that critics argued transgressed the spirit, if not the letter, of Posse Comitatus. From Little Rock in 1957 to Los Angeles in 1992, executive claims of necessity routinely collided with constitutional anxieties. These episodes were not simply about riots, rebellions, or integration. They were about the structure of federalism, the elasticity of emergency, and the historical habit of circumventing constraint when the moment demands action.

Here I trace five pivotal episodes, under Eisenhower, Johnson, Nixon, Reagan, and George H. W. Bush, each of which tested the constitutional and cultural boundary between the military and the domestic sphere. Together, they reveal a deeper story: not of sudden usurpations, but of steady normalization.

To be clear, I am not saying here that protection was unnecessary in the following cases. Segregation needed to end and other enforcement was necessary, but there is a not-so-fine line between law enforcement and the military to provide protection and enforce laws.

Dwight D. Eisenhower and Little Rock, 1957: Constitutional Duty or Military Overreach?

In September 1957, nine Black students attempted to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, under the mandate of Brown v. Board of Education. Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the students’ entry, openly defying a federal court order. President Dwight D. Eisenhower responded with what would become one of the most iconic domestic military deployments of the twentieth century. He federalized the Arkansas National Guard and deployed elements of the 101st Airborne Division to enforce desegregation.1

The Posse Comitatus Act was not directly violated, as Eisenhower invoked his authority under the Insurrection Act of 1807, which provides specific exceptions for the use of federal troops in situations where state authorities obstruct the enforcement of federal law. Yet constitutional scholars and critics at the time questioned the scope and permanence of such authority. Was this the narrow emergency the Act envisioned, or a federal imposition of social policy at the barrel of a gun?

Eisenhower himself was ambivalent. He viewed the action as a reluctant necessity, undertaken not out of ideological zeal but constitutional obligation. Yet in setting the precedent that federal troops could be used to enforce civil rights, he established a framework that would echo in subsequent decades. The military presence in Little Rock marked a moment where national will, embodied in the presidency, visibly overrode local sovereignty.

Lyndon B. Johnson and the Detroit Riots, 1967: The Language of Urban War

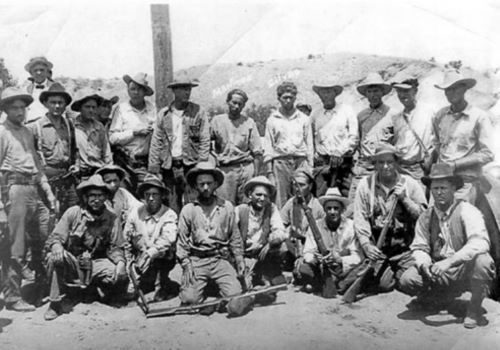

The late 1960s saw a series of urban uprisings rooted in racial injustice, police brutality, and economic disenfranchisement. The Detroit riots of July 1967 were among the most violent, resulting in forty-three deaths and over a thousand injuries. President Lyndon B. Johnson, already burdened by the political toll of Vietnam and domestic unrest, responded by deploying federal troops at the request of Michigan Governor George Romney.2

Here, too, the action technically complied with Posse Comitatus, as Johnson acted under the Insurrection Act at the behest of a state executive. Yet the nature and scale of the response troubled civil libertarians. The use of paratroopers in American neighborhoods, complete with tanks and aerial surveillance, blurred the line between military peacekeeping and police repression.

Johnson justified the action in humanitarian terms, insisting that federal troops were protecting lives and restoring order. But images of soldiers patrolling American streets, armed for war in a city already burning, challenged public perceptions of constitutional restraint. The crisis raised uncomfortable questions about proportionality and precedent. What, precisely, constituted an insurrection? Who determined the threshold? And did federal involvement extinguish unrest, or deepen alienation?

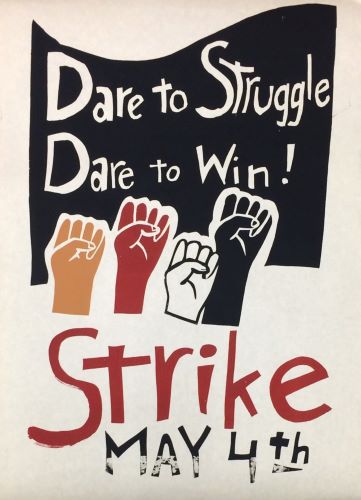

Richard Nixon and Kent State, 1970: Campus as Battlefield

Unlike Eisenhower and Johnson, President Richard Nixon did not directly deploy federal troops during the Kent State shooting in May 1970. The National Guard troops responsible for killing four students during an anti-war protest were under state authority. Yet Nixon’s broader strategy of encouraging crackdowns on campus protests, combined with FBI surveillance programs like COINTELPRO, made his administration complicit in a broader trend of militarized repression.3

Moreover, Nixon’s rhetoric often echoed martial themes. He framed dissent as internal threat, and treated domestic unrest as a form of low-level insurrection. His presidency marked a period in which federal executive power was deployed, covertly and administratively, against civilian protest movements.

Though the Kent State killings were not a formal violation of Posse Comitatus, they occurred in a constitutional environment where the executive had blurred the moral constraints that the Act was designed to express. Nixon’s willingness to use federal intelligence agencies for domestic political purposes, and his encouragement of state-level militarization, reflected a deeper erosion of civilian-military boundaries.

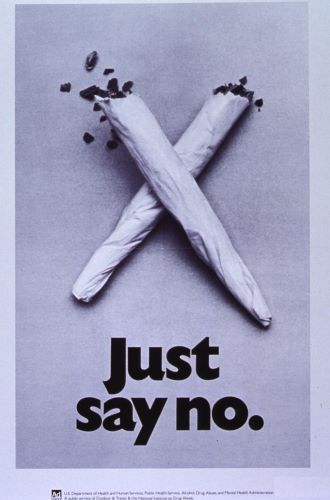

Ronald Reagan and the War on Drugs: Military Logic in Civil Space

By the 1980s, the Posse Comitatus Act was still technically intact, but its spirit had been substantially altered. The Reagan administration, in its zeal to combat the perceived scourge of drugs, undertook a dramatic redefinition of the military’s domestic role.

Through legislative amendments and executive pressure, Reagan expanded military involvement in drug interdiction, including intelligence sharing, training, equipment transfers, and, in some cases, operational support.4 The 1981 Military Cooperation with Law Enforcement Act loosened key restrictions, and the Department of Defense became increasingly embedded in domestic narcotics enforcement.

Though the military was not deployed to arrest civilians directly, its resources and authority seeped into civilian law enforcement. The war on drugs blurred the very distinctions Posse Comitatus sought to preserve. The militarization of policing, which critics would later link to SWAT team expansions and aggressive tactics, originated not in violation but in erosion.

Reagan’s legacy, in this respect, was not about a singular breach but a cultural shift. The language of war came to define the response to crime. Soldiers no longer marched through American cities, but their methods did.

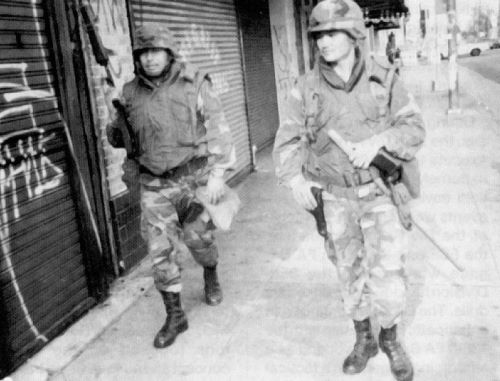

George H. W. Bush and the Los Angeles Riots, 1992: A Legal Echo Chamber

The last major episode in this trajectory occurred under President George H. W. Bush during the Los Angeles riots of April 1992, sparked by the acquittal of officers in the Rodney King beating. As violence engulfed the city, California Governor Pete Wilson requested federal assistance. Bush responded by deploying thousands of Army and Marine troops, again under the Insurrection Act.5

The legal procedure mirrored that of earlier interventions, and Bush publicly emphasized the coordination with state authorities. Yet the sheer scale of the deployment, and its rapid escalation, reflected a national comfort with military presence in domestic crises. Helicopters, armored vehicles, and curfews reconfigured the urban landscape.

What was once extraordinary had become routine. The use of military force in response to civilian unrest no longer provoked existential constitutional debate. The structure of the law remained intact, but the interpretive culture surrounding it had changed.

Conclusion: Legal Constraint and Political Habit

The Posse Comitatus Act was designed to prevent precisely the kind of normalization that these episodes illustrate. It was a law rooted not in efficiency but in suspicion—a recognition that the military, by design, does not operate under the same logic as civilian governance. Yet the twentieth century revealed how easily necessity becomes doctrine.

Presidents from Eisenhower to Bush did not shred the Constitution. They worked within its loopholes, often with public and legislative consent. Each claimed crisis. Each claimed coordination. Each insisted that the action was exceptional. Yet together, these moments form a pattern, a slow, methodical recalibration of the balance between force and freedom.

Today, the specter of militarization lingers not only in law but in expectation. The presence of troops in American streets no longer shocks. That may be the most lasting erosion of Posse Comitatus: not the breach, but the forgetfulness.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Mary L. Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 107–110.

- Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989), 331–340.

- James Miller, Democracy Is in the Streets: From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987), 287–294.

- Peter Andreas and Ethan Nadelmann, Policing the Globe: Criminalization and Crime Control in International Relations (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 112–118.

- Lou Cannon, Official Negligence: How Rodney King and the Riots Changed Los Angeles and the LAPD (New York: Times Books, 1997), 410–415.

Bibliography

- Andreas, Peter, and Ethan Nadelmann. Policing the Globe: Criminalization and Crime Control in International Relations. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Cannon, Lou. Official Negligence: How Rodney King and the Riots Changed Los Angeles and the LAPD. New York: Times Books, 1997.

- Dudziak, Mary L. Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Fine, Sidney. Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989.

- Miller, James. Democracy Is in the Streets: From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.23.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.