The sun was at once a creator, judge, emperor, and predator; its image refracted through the prism of human imagination, its light eternal yet always in need of human mediation.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The sun has been humanity’s most constant companion and, paradoxically, its most elusive mystery. Its warmth nourishes, its light governs time, and its disappearance each night enacts a drama of mortality and rebirth. Ancient civilizations did not merely revere the sun as a celestial object but embedded it into systems of power, law, and sacrifice. The worship of the sun, whether in the fertile valley of the Nile, the plains of Mesopotamia, or the stepped pyramids of Mesoamerica, reveals both a shared human impulse to sacralize the visible order of the cosmos and distinct cultural expressions of anxiety, hope, and sovereignty.

Egypt: The Radiance of Ra and the Politics of Eternity

Egyptian solar theology fused cosmic and political imagination with unusual intensity. Ra, often portrayed as a falcon-headed figure crowned with a blazing disk, was not only a life-giver but also the archetype of kingship. The Pharaoh, styled as the “Son of Ra,” was less a political ruler in the modern sense than the terrestrial incarnation of the divine solar principle.1 The authority of the king thus depended upon a cosmological claim: he embodied the cycle of light itself.

The mythic narrative of the sun’s daily voyage across the sky and through the perilous underworld each night articulated a theology of eternal recurrence. The dawn was more than a natural event; it was evidence of the Pharaoh’s successful mediation between cosmic chaos and terrestrial order.2 The radical solar reform of Akhenaten in the fourteenth century BCE, which elevated the Aten, the visible sun disk, as the sole deity, underscores how plastic yet powerful this imagery could be.3 Although Akhenaten’s monotheism was reversed after his death, the prominence of solar theology endured, embedding Egyptian kingship in a framework of cosmic renewal.

The centrality of solar worship also found expression in the very architecture of Egypt. The alignment of temples such as Karnak to the rising sun, and the design of the obelisk as a petrified ray of light, created a spatial theology in which stone itself captured the radiance of Ra. The architectural landscape reinforced the idea that Egypt’s endurance as a civilization was inseparable from the sun’s eternal presence. Ritual and monument thus fused into a single political theology: to rule Egypt was to embody the sunrise, and to build its temples was to inscribe the solar cycle into stone.4

Solar theology also carried profound eschatological significance. In funerary texts such as the Amduat, the deceased Pharaoh was envisioned as traveling with Ra through the underworld, merging his fate with the daily renewal of the sun. The promise of rebirth after death was not only royal but aspirational for all Egyptians who could participate, through ritual and inscription, in the Pharaoh’s solar destiny. In this way, the sun was both a cosmological constant and a personal hope for immortality. Egyptian solar worship thus operated simultaneously at the level of empire and the level of the soul.5

Mesopotamia: Shamash and the Judgement of Light

In the great river valleys of Mesopotamia, the sun found expression not primarily as a creator but as an arbiter. Shamash, the solar deity, presided over justice. His light was imagined as piercing all obscurity, revealing hidden crimes, and exposing falsehood. This conceptualization emerges vividly in the Code of Hammurabi, where the king is depicted receiving the law directly from Shamash.6 The sun here serves as guarantor of equity, legitimizing human legal codes as reflections of cosmic order.

Such imagery was not merely symbolic. Mesopotamian kings ruled within a cultural expectation that law derived its authority from the divine light. By locating justice in the radiance of Shamash, the civilization constructed a theocratic jurisprudence that bound human rulers to heavenly oversight. Unlike Egyptian solar cults, which emphasized rebirth and continuity, Mesopotamian solar religion highlighted ethical transparency and accountability before an all-seeing light.

Greece and Rome: From Helios to Sol Invictus

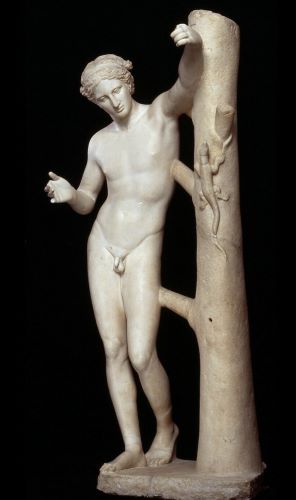

The Greek tradition offered a more mythopoetic account of solar divinity. Helios, who drove his chariot across the heavens, embodied the regularity of time and the clarity of vision. Apollo, though initially a separate deity, absorbed solar qualities, becoming patron of reason, prophecy, and the harmonies of music.7 This fusion of light with intellect reflects the Greek impulse to marry cosmology with rational order.

Greek literature itself often portrayed the sun as a witness to oaths and treaties, evoking the sense that no human action could escape its gaze. Homer invoked Helios as a guarantor of divine justice in the Odyssey, when the slaughter of the god’s sacred cattle brought ruin to Odysseus’ crew.8 Here the sun was not only a measure of time but a moral force, punishing those who transgressed cosmic law. Such episodes reveal that solar divinity was both poetic metaphor and religious power, shaping cultural notions of accountability and fate.

Rome, inheriting and reshaping this solar inheritance, elevated Sol Invictus, the “Unconquered Sun,” during the late empire. Under Emperor Aurelian in the third century CE, the cult became a unifying imperial theology.9 The sun, eternal and undefeated, mirrored Rome’s aspiration for dominion and endurance. The festival of Sol Invictus, celebrated on December 25, later provided fertile soil for Christian appropriation, as Christ came to be figured as the true light of the world. Here, solar worship illustrates the permeability of religious symbolism, where cosmic imagery migrated from pagan ritual into Christian theology without losing its emotive resonance.

Mesoamerica: Blood for the Fifth Sun

In Mesoamerica, solar religion reached a visceral intensity unparalleled elsewhere. Among the Maya, Kinich Ahau embodied the sun’s dual nature, nurturing yet destructive, brilliant yet jaguar-clawed. Temples were aligned to solstices and equinoxes, making the architecture itself a liturgical calendar.10 Kingship, as in Egypt, bore solar weight, for rulers claimed descent from or identification with the sun.

The Aztecs pressed this theology into an even more urgent register. They believed the cosmos existed in a precarious Fifth Sun, each previous age destroyed in catastrophe. To prevent cosmic collapse, the sun had to be nourished by human blood. The god Huitzilopochtli, patron of sun and war, demanded sacrifice as the engine of cosmic order.11 Hearts offered on the Templo Mayor were not ritual excess but existential necessity. The sun’s rising was imagined not as given but as earned through ritual violence.

This theology intertwined empire and cosmos: warfare became sacred, since it provided the captives required to sustain the sun. Unlike Egypt’s vision of eternal recurrence or Mesopotamia’s focus on justice, Mesoamerican solar worship dramatized fragility. The sun could falter. The cosmos could collapse. Only human devotion, expressed in sacrifice, forestalled annihilation.

Comparative Reflections: Light, Law, and Sacrifice

The comparative record reveals both unity and divergence. The sun consistently became the axis of political authority, whether in Pharaoh’s divine kingship, Hammurabi’s judicial mandate, Rome’s imperial cult, or Aztec sacrificial empire. Yet each tradition projected distinct concerns onto the solar canvas. For Egypt, the sun meant renewal and eternal return. For Mesopotamia, it was judgment and moral clarity. For Rome, it symbolized endurance and dominion. For Mesoamerica, it was fragility, violence, and precarious survival.

Such differences matter. They demonstrate that while the human gaze on the sun was universal, the meanings drawn from it were profoundly shaped by cultural anxieties and social needs. The sun’s constancy offered reassurance, yet its daily disappearance invited mythologies of danger. Civilizations answered that riddle differently, whether with law, sacrifice, or theological innovation.

Conclusion

Sun worship in ancient civilizations illustrates humanity’s impulse to sacralize the visible order of nature. The sun was not merely a celestial body but a mirror of political order, ethical obligation, and existential dread. By tracing its varied cults across Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome, and Mesoamerica, we glimpse how a single natural phenomenon could anchor radically different visions of reality. The sun was at once a creator, judge, emperor, and predator; its image refracted through the prism of human imagination, its light eternal yet always in need of human mediation.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Erik Hornung, Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982), 37.

- Jan Assmann, The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002), 52–56.

- James K. Hoffmeier, Akhenaten and the Origins of Monotheism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 73–79.

- Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000), 41–44.

- Erik Hornung, The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999), 15–18.

- Leo Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964), 171.

- Walter Burkert, Greek Religion (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985), 120–124.

- Homer, Odyssey, trans. Robert Fagles (New York: Penguin, 1996), Book 12.

- Robert Turcan, The Cults of the Roman Empire (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996), 197.

- Linda Schele and David Freidel, A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya (New York: William Morrow, 1990), 103–109.

- T.J. Knab, “Metaphors, Concepts, and Coherence in Aztec,” in Symbol and Meaning Beyond the Closed Community: Essays in Mesoamerican Ideas, ed. Gary Gossen (Albany: Institute for Mesoamerican Studies, 1986), 48.

Bibliography

- Assmann, Jan. The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Hoffmeier, James K. Akhenaten and the Origins of Monotheism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Hornung, Erik. Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982.

- Hornung, Erik. The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999.

- Homer. Odyssey. Translated by Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin, 1996.

- Knab, T.J. “Metaphors, Concepts, and Coherence in Aztec.” In Symbol and Meaning Beyond the Closed Community: Essays in Mesoamerican Ideas, edited by Gary Gossen, 45-56. Albany: Institute for Mesoamerican Studies, 1986.

- Oppenheim, A. Leo. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964.

- Schele, Linda, and David Freidel. A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. New York: William Morrow, 1990.

- Turcan, Robert. The Cults of the Roman Empire. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.27.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.