Petroleum endowed the state with extraordinary fiscal power, geopolitical relevance, and the capacity to modernize at a pace unmatched in much of Latin America.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Oil as Destiny and Trap

Few nations have been shaped so completely by a single resource as Venezuela. From the early twentieth century onward, petroleum transformed the country’s economy, political institutions, social hierarchies, and international position with extraordinary speed. Oil did not merely generate revenue. It reordered the relationship between state and society, altered patterns of development, and fostered expectations of abundance that became deeply embedded in national identity. In Venezuela, oil functioned simultaneously as a source of sovereignty and as a structural constraint, offering the promise of modernity while narrowing the paths by which that promise could be realized.

Historians and political economists have long warned against treating Venezuela’s trajectory as an inevitable “resource curse.” Such formulations risk flattening history into determinism, as though oil itself mechanically produced authoritarianism, corruption, or collapse. A more careful reading reveals something subtler and more troubling. Petroleum wealth interacted with weak institutions, concessionary regimes, and rent-centered governance to create a political economy in which the state derived power not from taxation or broad-based production, but from control over externally generated rents.1 Oil thus reshaped the incentives of governance itself, encouraging centralization, patronage, and short-term distribution over long-term diversification.

This dynamic produced what Fernando Coronil famously described as the “magical state,” a government perceived as capable of conjuring wealth from the subsoil without demanding reciprocal sacrifice from its citizens.2 The illusion of effortless abundance masked the fragility beneath. Because oil revenues flowed independently of domestic productivity, the state expanded rapidly while remaining structurally detached from society. Political legitimacy became tied to distribution rather than representation, and economic planning revolved around managing windfalls rather than cultivating resilience. Over time, this arrangement weakened agriculture, distorted industrial development, and left the nation acutely vulnerable to fluctuations in global energy markets.

Yet oil also enabled genuine achievements. Petroleum revenues financed infrastructure, education, urban growth, and periods of democratic stability, particularly in the mid-twentieth century. These gains complicate narratives that portray Venezuela’s oil history as an unbroken descent into dysfunction. The central problem was not the presence of oil, but the political and institutional choices made in response to it. States that rely heavily on resource rents often struggle to build the bureaucratic discipline and fiscal accountability necessary for sustainable development, especially when early abundance delays hard structural reforms.3 Venezuela exemplifies this paradox with unusual clarity.

Understanding oil as both destiny and trap is therefore essential. Petroleum endowed Venezuela with extraordinary leverage in the global economy and unprecedented fiscal capacity at home. At the same time, it narrowed the country’s developmental imagination, locking successive governments into cycles of boom, overreach, and crisis. This essay traces that history not as a morality tale, but as a long struggle over sovereignty, power, and the meaning of prosperity in a nation where wealth emerged not from labor or land, but from beneath the earth itself.4

Before Petroleum Capitalism: Indigenous Knowledge and Early Encounters

Long before petroleum became a commodity of global consequence, oil was already part of the lived landscape of what is now Venezuela. Natural seepages, commonly referred to as mene, were visible in multiple regions, especially around the Maracaibo Basin.5 These seepages were not “discoveries” waiting for modern industry, but familiar features of place, known through long observation and practical experience. The historical significance of this fact is simple: oil existed within a local ecology of use before it existed within a global economy of extraction.6

Indigenous communities used mene in materially pragmatic ways. The substance was applied as a waterproofing and sealing material, particularly useful in humid environments where moisture threatened canoes, containers, and tools.7 It was also used in healing practices, where its physical properties made it useful for treating skin conditions and wounds.8 These uses did not require drilling, capital investment, or large-scale infrastructure. They were adaptive practices within established lifeways, which treated oil as one resource among many rather than the organizing axis of society.9

Colonial observers encountered oil seepages early and recorded them as part of their descriptions of the region, particularly in relation to the lake country and coastal zones.10 The presence of pitch-like substances could invite speculation about utility, including waterproofing and maritime applications, but such references rarely translated into systematic exploitation.11 The reason was not ignorance. It was that colonial extraction prioritized commodities that fit existing imperial circuits, while petroleum lacked both the technological pathway and the market demand to become fiscally decisive.12

This limited colonial interest is historically clarifying. Oil did not become transformative simply because it was present underground or on the surface. It became transformative when a particular set of conditions aligned: industrial technologies capable of large-scale production and refining, a global energy economy hungry for petroleum, and political arrangements that permitted outside capital to control access and profits.13 Before that convergence, oil was materially real but economically peripheral. The later dominance of petroleum, therefore, was not a straight line from nature to destiny. It was a rupture shaped by modernity’s demands.14

Recognizing this pre-capitalist phase matters because it prevents a common interpretive mistake. Venezuela’s twentieth-century oil dependency is often narrated as inevitability, as though the subsoil carried a political program. The deeper historical record suggests the opposite. Oil’s meaning changed when power changed, when market logics displaced local logics, and when extraction became the governing framework for land, labor, and state authority.15 The early history of mene is therefore not a quaint prologue. It is evidence that petroleum’s later dominance was historically made, not naturally ordained.16

The Birth of the Oil Economy, 1914–1935

The modern oil economy in Venezuela began in 1914 with the successful drilling of the Zumaque I well in the foothills of the Maracaibo Basin, a discovery widely regarded as the first sustained instance of commercial petroleum production in the country.17 Unlike earlier encounters with surface seepages, Zumaque I demonstrated that Venezuelan oil could be extracted in industrial quantities and sold profitably on international markets. This moment coincided with rising global demand driven by mechanized industry and naval militarization, situating Venezuela almost immediately within a rapidly expanding energy economy. The country entered this new order abruptly, without a regulatory framework or administrative capacity designed to manage such transformation.18

Production expanded through concessionary agreements that transferred extensive rights to foreign firms, a process overseen by the authoritarian government of Juan Vicente Gómez. These concessions granted companies control over exploration, extraction, and infrastructure in exchange for royalties and limited taxation, embedding foreign capital at the core of the emerging oil economy. The state benefited fiscally from these arrangements, but the structure discouraged direct oversight and institutional development, binding public authority to rent collection rather than governance. This early dependency shaped the incentives of the Venezuelan state from the outset.19

The decisive turning point came in 1922 with the Los Barrosos No. 2 blowout near Cabimas, when an uncontrolled gusher released massive quantities of oil for days, dramatically illustrating the scale of Venezuela’s petroleum reserves.20 International observers and investors quickly grasped the implications, and foreign capital surged into the Maracaibo Basin. Oil production expanded at a pace unmatched in the region, and within a few years petroleum displaced agriculture as the country’s principal export. By 1928, Venezuela had become the world’s leading oil exporter, a transformation achieved in less than a decade.21

Foreign dominance was a defining feature of this boom. U.S. and European firms controlled nearly all production and export operations, operating through subsidiary structures that insulated parent companies from local political risk. Oil camps and company towns developed as enclaves around Lake Maracaibo, physically separated from surrounding communities and governed by corporate authority rather than national law.22 These zones were oriented outward toward global markets, reinforcing economic dependency while limiting the diffusion of technical knowledge and decision-making power within Venezuelan society.

Oil revenues profoundly altered political authority during this period. The Gómez regime used petroleum income to consolidate power, modernize the military, and reduce reliance on domestic taxation, thereby weakening incentives for political inclusion or institutional accountability.23 Fiscal strength increased while administrative depth remained shallow, producing a state capable of distributing rents but poorly equipped to regulate economic development. Oil thus reshaped governance itself, reinforcing authoritarian stability through financial autonomy rather than popular legitimacy.24

By the time of Gómez’s death in 1935, the contours of Venezuela’s oil economy were firmly established. Petroleum accounted for the overwhelming majority of export earnings, while agriculture and manufacturing declined in relative importance. The early oil era left a dual legacy: unprecedented fiscal capacity paired with long-term structural vulnerability. The patterns formed between 1914 and 1935 would persist, shaping later struggles over sovereignty, law, and national development.25

Oil and Structural Distortion: Dependency and “Dutch Disease”

As petroleum revenues expanded during the early and mid-twentieth century, Venezuela’s economy underwent a profound structural reorientation. Oil rapidly displaced agriculture and manufacturing as the central pillar of national income, not through gradual competition but through sheer fiscal dominance. Export earnings became overwhelmingly concentrated in petroleum, while other sectors stagnated or declined in relative importance. By the 1930s, oil revenues had begun to decouple state finances from domestic production, creating an economy increasingly oriented toward rent extraction rather than value creation.26 This shift marked the beginning of a long-term distortion that reshaped development priorities and institutional incentives.

One of the most visible consequences was the erosion of agriculture. As oil dollars flowed into the state, exchange rates appreciated, making agricultural exports less competitive on international markets. Rural labor migrated toward oil zones and urban centers, drawn by higher wages and state spending fueled by petroleum income. Food production increasingly lagged behind consumption, binding Venezuela to imports even as export earnings surged.27 The countryside hollowed out not because agriculture was unviable in absolute terms, but because oil rents tilted the economic field so decisively that alternative forms of production struggled to survive.

This pattern aligns with what later economists would describe as “Dutch Disease,” a condition in which resource booms undermine broader economic diversification by distorting prices, labor allocation, and investment flows. In Venezuela, the effects were amplified by the speed and scale of oil expansion. Capital, infrastructure, and policy attention gravitated toward petroleum, while manufacturing remained shallow and dependent on imports.28 Industrial development occurred, but it was often tied to oil revenues rather than independent productive capacity, leaving it vulnerable to fluctuations in global energy markets.

The structural consequences extended beyond economics into governance. Because oil revenues accrued directly to the state, public authority grew increasingly detached from society. Fiscal strength no longer depended on taxing citizens or fostering domestic enterprise, but on managing external rents.29 This weakened incentives for accountability and long-term planning, encouraging distributive politics over institutional reform. Economic policy focused on allocating oil income rather than building resilient production systems, reinforcing dependency even during periods of apparent prosperity.

These distortions did not produce immediate collapse. On the contrary, oil wealth enabled periods of growth, urbanization, and social mobility that masked underlying fragility. Yet the very success of petroleum concealed the costs of imbalance. When oil prices fell or production faltered, the absence of diversified economic foundations became starkly visible.30 The structural distortions introduced by oil thus functioned as a delayed constraint, embedding vulnerability into the political economy long before crisis made it visible.

The Struggle for Sovereignty: Law, Reform, and Nationalization

By the late 1930s and early 1940s, Venezuela’s political leadership increasingly recognized that foreign dominance over petroleum extraction posed a fundamental challenge to national sovereignty. Although oil revenues had transformed state finances, decision-making authority remained largely outside the country, embedded in concessionary contracts that favored foreign firms. Reformers argued that without legal intervention, petroleum wealth would continue to strengthen the state fiscally while hollowing it out politically. This concern crystallized around efforts to redefine the legal relationship between the state and oil companies, beginning with incremental reforms rather than outright expropriation.31

The most significant of these early reforms was the Hydrocarbons Law of 1943, which restructured concession terms and sharply increased the state’s share of oil profits. The law standardized contracts, limited concession durations, and established the principle that the Venezuelan state was the ultimate owner of subsoil resources. Most consequentially, it introduced a profit-sharing framework that effectively moved the state toward a fifty-fifty division of oil income, altering the balance of power between the government and foreign producers.32 This legal shift did not dismantle foreign control, but it decisively constrained it within a stronger regulatory framework.

The 1943 law also marked an important institutional turning point. By asserting regulatory authority, the state began to develop technical and bureaucratic capacity to oversee the oil sector, laying the groundwork for future national control. Oil policy became a central arena of political debate, linked to broader struggles over democracy, development, and social reform.33 Sovereignty was no longer framed solely in territorial terms, but increasingly in economic and legal ones, with petroleum at the core of national self-definition.

Venezuela’s international posture further evolved with its role in founding the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1960. Through OPEC, Venezuela sought to coordinate production policies with other oil-producing states in order to stabilize prices and counter the dominance of multinational oil companies.34 Membership reflected a strategic shift from unilateral regulation toward collective action, situating Venezuelan oil policy within a global framework of producer-state cooperation while reinforcing claims to sovereign control over natural resources.

The culmination of these long-term efforts came in 1976 with the formal nationalization of the oil industry. Under the administration of Carlos Andrés Pérez, the state assumed ownership of oil operations previously controlled by foreign firms, consolidating them under the national oil company Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA).35 Nationalization was presented not as a rupture but as the logical fulfillment of decades of legal and political evolution, preserving technical expertise while transferring ownership and strategic authority to the state.

Yet nationalization did not resolve the deeper tensions embedded in Venezuela’s oil economy. While ownership shifted, the state remained dependent on petroleum rents, and the technocratic management of PDVSA insulated oil policy from broader democratic oversight.36 Sovereignty over resources expanded, but the structural dependence on oil persisted, setting the stage for future conflicts over control, distribution, and political power. The struggle for sovereignty thus achieved a historic victory in form, even as its substance remained constrained by the enduring logic of the rentier state.

Venezuela and the Global Oil Order: OPEC and the 1970s Windfall

Venezuela’s position in the global oil system shifted decisively with the creation of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries in 1960, an initiative designed to counter the price-setting power of multinational oil companies and stabilize revenues for producing states. As a founding member, Venezuela sought to leverage collective action to defend sovereign control over production and pricing, embedding national oil policy within a broader international framework.37 This move reflected a strategic recalibration: sovereignty would be pursued not only through domestic law, but through coordinated participation in global markets increasingly shaped by producer power.

The impact of this strategy became unmistakable in the early 1970s. The oil price shocks of 1973–1974, triggered by geopolitical conflict and coordinated supply constraints, produced an unprecedented surge in petroleum revenues for exporting states. Oil prices multiplied within a short span, and Venezuela experienced a dramatic fiscal windfall as export earnings soared.38 The sudden influx of revenue expanded the state’s capacity to spend, borrow, and plan on a scale previously unimaginable, reinforcing the belief that oil could underwrite rapid modernization and social transformation.

The windfall, however, carried structural consequences. Massive state spending accelerated urban growth, expanded public employment, and financed ambitious development projects, many of which assumed that high oil prices would persist indefinitely. Capital inflows and currency appreciation further weakened non-oil sectors, deepening dependence on petroleum income while masking inefficiencies.39 The abundance of revenue reduced fiscal discipline and encouraged policy decisions oriented toward short-term distribution rather than long-term diversification, entrenching vulnerabilities beneath the appearance of prosperity.

By the end of the decade, the limits of this model were becoming visible. When oil prices softened and global conditions shifted, Venezuela confronted rising debt, inflationary pressure, and an economy ill-prepared to adjust. The 1970s windfall had strengthened the state’s global standing and fiscal reach, but it also intensified the very distortions that would later magnify crisis.40 Venezuela’s experience within OPEC thus revealed a central paradox of oil power: collective leverage could reshape markets, yet windfall gains, unmanaged, could undermine the foundations of economic stability.

From Oil Democracy to Oil Populism: Chávez and Maduro

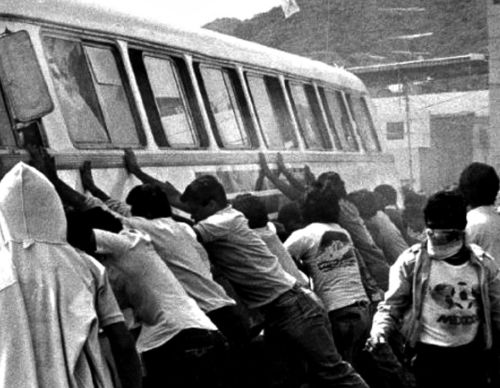

By the late twentieth century, Venezuela’s oil-centered political system had entered a period of visible strain. The collapse of oil prices in the 1980s, mounting debt, and austerity measures eroded public confidence in the established party system that had governed since the mid-century democratic settlement. Popular frustration culminated in social unrest, most notably the 1989 Caracazo, when protests against economic reforms were met with state violence, exposing the fragility of Venezuela’s oil-funded democracy.41 These crises created the conditions for a political realignment in which oil would once again serve as the central instrument of power, this time under a populist rather than technocratic framework.

Hugo Chávez’s election in 1998 marked a decisive shift in the political meaning of oil. Campaigning against elite mismanagement and inequality, Chávez framed petroleum wealth as a collective inheritance that had been betrayed by existing institutions. Once in office, he moved to reassert political control over the oil sector, revising hydrocarbon laws, increasing state participation, and redirecting oil revenues toward expansive social programs.42 Oil thus became not merely a source of state income but a direct mechanism of political mobilization, linking redistribution to personal leadership rather than institutional mediation.

This transformation fundamentally altered the role of Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA). Previously insulated as a technocratic entity, the company was increasingly subordinated to executive authority, especially after the 2002–2003 oil strike and subsequent purge of experienced personnel.43 Technical expertise gave way to political loyalty as the primary criterion for control, weakening operational capacity while deepening the fusion between oil revenues and partisan governance. The state’s reliance on petroleum intensified even as its ability to manage the industry effectively declined.

Under Nicolás Maduro, these dynamics accelerated amid deteriorating economic conditions. Falling oil prices after 2014 exposed the vulnerability of a system heavily dependent on petroleum exports, while mismanagement and underinvestment further reduced production capacity.44 The government responded by expanding monetary financing and tightening political control, producing hyperinflation, shortages, and a sharp contraction of living standards. Oil remained central to state power, but its material base was eroding, undermining both economic stability and political legitimacy.

The Chávez and Maduro years thus represent not a rupture with Venezuela’s oil history, but an intensification of its core contradictions. Petroleum continued to fund political authority, yet its use shifted from sustaining institutional democracy to reinforcing personalist rule.45 Oil populism expanded access to resources for some while hollowing out the structures required for long-term governance. The result was a system in which control over oil remained paramount, even as the foundations of the oil economy itself began to collapse.

Collapse and Consequences: Sanctions, Decline, and Mass Emigration

By the mid-2010s, Venezuela’s oil-centered political economy entered a phase of systemic collapse. Years of underinvestment, declining technical capacity, and politicized management had already weakened production, and the sharp fall in global oil prices after 2014 exposed the fragility of a system overwhelmingly dependent on petroleum exports. Oil revenues, which had financed imports and public spending, contracted abruptly, leaving the state without the foreign exchange needed to sustain basic economic functions.46 The crisis was not sudden, but cumulative, the result of long-term structural dependence colliding with adverse global conditions.

Oil production itself deteriorated at a dramatic pace. Output fell from roughly three million barrels per day in the late 1990s to well under one million barrels per day by the late 2010s, reflecting equipment decay, loss of skilled labor, and operational failures across the oil sector.47 Refining capacity collapsed alongside production, producing fuel shortages in a country once synonymous with oil abundance. The erosion of technical expertise and maintenance capacity transformed petroleum from an engine of state power into a bottleneck constraining economic survival.

International sanctions intensified these dynamics. Beginning in the late 2010s, U.S. sanctions restricted Venezuela’s access to financial markets and limited its ability to export oil, particularly to its largest historical customers.48 These measures sharply reduced cash flow and complicated efforts to stabilize production, accelerating economic contraction. While sanctions did not cause the collapse, they magnified its effects by constraining the state’s remaining options, turning an already severe crisis into a humanitarian emergency.

The economic consequences were devastating. Hyperinflation eroded wages and savings, while shortages of food, medicine, and basic goods became widespread.49 Public services deteriorated as state revenues collapsed, and living standards fell precipitously. Oil wealth, once the guarantor of social stability, now symbolized institutional failure, as the state struggled to convert dwindling petroleum resources into meaningful economic relief.

One of the most visible outcomes of this collapse was mass emigration. Millions of Venezuelans left the country in search of work, food, and security, producing one of the largest displacement crises in modern Latin American history.50 Migration patterns reflected not only economic desperation but the erosion of social trust and political legitimacy, as citizens concluded that the oil state could no longer provide even minimal stability. The demographic impact reshaped families, labor markets, and regional politics across the hemisphere.

The collapse of Venezuela’s oil economy thus produced consequences far beyond energy markets. Sanctions, mismanagement, and structural dependence converged to undermine state capacity, fracture society, and displace millions.51 What had once been a resource of extraordinary leverage became a constraint on recovery, binding the country’s future to unresolved questions of governance, diversification, and sovereignty. The final stage of oil dependence revealed its deepest cost: not merely economic decline, but the unraveling of social and political life itself.

Conclusion: Oil as Power, Oil as Prison

Venezuela’s history with oil reveals a paradox that unfolded over more than a century. Petroleum endowed the state with extraordinary fiscal power, geopolitical relevance, and the capacity to modernize at a pace unmatched in much of Latin America. At the same time, it reshaped political incentives in ways that weakened institutional development, narrowed economic diversification, and detached governance from productive society. Oil became a source of authority precisely because it allowed the state to rule without sustained consent, binding political power to control over rents rather than to representation or accountability.52

The long arc of this history underscores that Venezuela’s crisis cannot be explained by oil alone. Petroleum did not mechanically produce authoritarianism, populism, or collapse. Instead, it interacted with legal structures, global markets, and domestic political choices to create a system that rewarded short-term distribution over long-term resilience. Periods of prosperity repeatedly postponed reform, while downturns exposed the absence of institutional buffers. The result was a political economy capable of absorbing shocks only when prices were high, and dangerously brittle when they were not.53

This pattern also complicates simple narratives of sovereignty. Legal reforms, OPEC membership, and nationalization expanded formal control over resources, yet they did not resolve the deeper dependency on oil revenues as the foundation of state power. Ownership shifted, but vulnerability remained. As petroleum increasingly financed political loyalty rather than institutional capacity, control over oil became both the means of governance and its greatest constraint.54 The prison was not oil itself, but the structures built around it.

The Venezuelan case offers a cautionary lesson with relevance far beyond its borders. Resource wealth can amplify state capacity, but without diversification, accountability, and durable institutions, it can also hollow out the foundations of governance. Venezuela’s experience shows how abundance can delay reckoning, how sovereignty can coexist with dependency, and how power drawn from the subsoil can ultimately undermine the social contract above it. The unresolved challenge remains whether Venezuela can imagine a future no longer organized around oil as destiny, but as history.55

Appendix

Footnotes

- Terry Lynn Karl, The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

- Fernando Coronil, The Magical State: Nature, Money, and Modernity in Venezuela (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

- Karl, The Paradox of Plenty.

- Hazem Beblawi and Giacomo Luciani, eds., The Rentier State (London: Croom Helm, 1987).

- Coronil, The Magical State.

- Coronil, The Magical State.

- Miguel Tinker Salas, The Enduring Legacy: Oil, Culture, and Society in Venezuela (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009).

- Salas, The Enduring Legacy.

- Coronil, The Magical State; Salas, The Enduring Legacy.

- Coronil, The Magical State.

- Salas, The Enduring Legacy.

- Coronil, The Magical State.

- Salas, The Enduring Legacy.

- Coronil, The Magical State.

- Salas, The Enduring Legacy.

- Coronil, The Magical State.

- Edwin Lieuwen, Petroleum in Venezuela: A History (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1954), 41–43.

- Lieuwen, Petroleum in Venezuela, 44–50.

- Lieuwen, Petroleum in Venezuela, 51–60.

- Lieuwen, Petroleum in Venezuela, 61–68.

- Brian S. McBeth, Juan Vicente Gómez and the Oil Companies in Venezuela, 1908–1935 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 49–78.

- McBeth, Juan Vicente Gómez and the Oil Companies in Venezuela, 79–102.

- Lieuwen, Petroleum in Venezuela, 69–75.

- Lieuwen, Petroleum in Venezuela, 76–88.

- Coronil, The Magical State, 75–83.

- Lieuwen, Petroleum in Venezuela, 76–88.

- Coronil, The Magical State, 85–103.

- Karl, The Paradox of Plenty, 43–67.

- McBeth, Juan Vicente Gómez and the Oil Companies in Venezuela, 109–132.

- Asdrúbal Baptista, Bases cuantitativas de la economía venezolana, 1830–2000 (Caracas: Fundación Empresas Polar, 2002), 215–240.

- McBeth, Juan Vicente Gómez and the Oil Companies in Venezuela, 173–189.

- Lieuwen, Petroleum in Venezuela, 132–148.

- Baptista, Bases cuantitativas de la economía venezolana, 181–194.

- Francisco Parra, Oil Politics: A Modern History of Petroleum (London: I.B. Tauris, 2003), 161–170.

- Lieuwen, Petroleum in Venezuela, 214–227.

- Karl, The Paradox of Plenty, 92–118.

- Parra, Oil Politics, 147–165.

- Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990), 585–617.

- Baptista, Bases cuantitativas de la economía venezolana, 241–270.

- Karl, The Paradox of, 119–150.

- Baptista, Bases cuantitativas de la economía venezolana, 309–330.

- Julia Buxton, The Failure of Political Reform in Venezuela (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001), 95–123.

- Francisco Monaldi, “The Political Economy of Oil Contract Renegotiation in Venezuela,” in Beyond the Resource Curse, ed. Brenda Shaffer and Taleh Ziyadov (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 131–154.

- International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook: Regional Economic Outlook—Western Hemisphere (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, various years).

- Javier Corrales and Michael Penfold, Dragon in the Tropics: Hugo Chávez and the Political Economy of Revolution in Venezuela, 2nd ed. (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2015), 201–230.

- Baptista, Bases cuantitativas de la economía venezolana, 331–360.

- International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration, “Venezuela Country Analysis Brief,” various years.

- Congressional Research Service, Venezuela: Background and U.S. Relations (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, updated editions, 2019–2022).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Venezuelan Situation: Regional Refugee and Migrant Response (Geneva: UNHCR, annual reports).

- World Bank, Venezuela Economic Update (Washington, DC: World Bank, selected reports, 2018–2022).

- Karl, The Paradox of Plenty, 1–23.

- Coronil, The Magical State, 3–18.

- Corrales and Penfold, Dragon in the Tropics, 231–260.

- Lieuwen, Petroleum in Venezuela, 309–324.

Bibliography

- Baptista, Asdrúbal. Bases cuantitativas de la economía venezolana, 1830–2000. Caracas: Fundación Empresas Polar, 2002.

- Beblawi, Hazem, and Giacomo Luciani, eds. The Rentier State. London: Croom Helm, 1987.

- Buxton, Julia. The Failure of Political Reform in Venezuela. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001.

- Congressional Research Service. Venezuela: Background and U.S. Relations. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Updated editions, 2019–2022.

- Coronil, Fernando. The Magical State: Nature, Money, and Modernity in Venezuela. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

- Corrales, Javier, and Michael Penfold. Dragon in the Tropics: Hugo Chávez and the Political Economy of Revolution in Venezuela. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2015.

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook: Regional Economic Outlook—Western Hemisphere. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, various years.

- Karl, Terry Lynn. The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

- Lieuwen, Edwin. Petroleum in Venezuela: A History. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1954.

- McBeth, Brian S. Juan Vicente Gómez and the Oil Companies in Venezuela, 1908–1935. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Monaldi, Francisco. “The Political Economy of Oil Contract Renegotiation in Venezuela.” In Beyond the Resource Curse, edited by Brenda Shaffer and Taleh Ziyadov, 131–154. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

- Parra, Francisco. Oil Politics: A Modern History of Petroleum. London: I.B. Tauris, 2003.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Venezuelan Situation: Regional Refugee and Migrant Response. Geneva: UNHCR, annual reports.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. “Venezuela Country Analysis Brief.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Energy. Various years.

- World Bank. Venezuela Economic Update. Washington, DC: World Bank. Selected reports, 2018–2022.

- Yergin, Daniel. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.23.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.