Civilization, as it was constructed by early modern empires, depended less on what it revealed than on what it concealed.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Civilization as Alibi

European colonial empires did not conquer the world in silence. They arrived armed not only with soldiers, ships, and law, but with stories. From the sixteenth century onward, conquest was wrapped in a moral language that portrayed domination as improvement and violence as necessity. Empire presented itself as a civilizing force, a bearer of order, reason, Christianity, and progress to societies framed as deficient or backward. This narrative did not merely accompany expansion. It justified it. Civilization became an alibi, a way to obscure brutality behind claims of uplift.

The language of civilization allowed imperial violence to appear both regrettable and righteous. Mass displacement, enslavement, and the destruction of social systems were reframed as transitional pains on the road to progress, necessary disruptions in the march toward order and rational governance. Indigenous resistance was rarely described as self defense; instead it was cast as disorder, savagery, or irrational opposition to improvement, a refusal to accept the benefits of empire. This rhetorical move was powerful because it inverted responsibility. Violence no longer belonged to the conqueror but to the conquered, whose alleged backwardness made force seem unavoidable. By redefining coercion as correction and domination as guidance, colonial powers insulated themselves from moral accountability and converted aggression into obligation.

This transformation of violence into benevolence depended on historical control. Empires did not simply commit atrocities and move on. They actively curated memory. Official histories celebrated explorers, administrators, and missionaries while minimizing or omitting the human cost of empire. The archive itself became selective, shaped by those who wielded power and excluded those who endured its consequences. What survived as history was not a neutral record but a constructed narrative designed to stabilize authority and suppress guilt.

Understanding civilization as alibi matters because its effects did not end with formal empire. The same logic that reframed conquest as progress shaped education, museums, and public memory in the metropole, embedding sanitized narratives into everyday civic life. Children learned heroic stories of expansion stripped of coercion, stories that emphasized discovery, innovation, and governance while erasing enslavement and displacement. Cultural institutions displayed colonized societies as objects of curiosity, beauty, or disappearance, often severed from the violence that made such displays possible. These were not accidental omissions or products of ignorance. They were continuations of a long tradition of historical sanitization, one that trained generations to admire imperial achievement without confronting its human cost and that continues to shape contemporary debates over memory, heritage, and national innocence.

The Birth of the Civilizing Narrative

The civilizing narrative did not emerge fully formed with overseas conquest. It developed gradually within Europe as a way of ranking societies according to perceived moral, religious, and cultural development. Late medieval and early modern thinkers increasingly framed history as a linear progression from disorder to refinement, a framework that placed Christian Europe at its apex. This hierarchical understanding of human societies created the intellectual conditions necessary for empire, long before imperial violence became global in scale. By the time European states expanded aggressively beyond the continent, they already possessed a language that rendered inequality natural and domination defensible.

Renaissance humanism played a crucial role in shaping this worldview. Classical texts were rediscovered and repurposed to support ideals of rationality, civic order, and cultivated virtue, traits that humanists associated with civilized life. Yet these ideals were never universal in application. They were bounded by race, religion, and geography. Peoples who did not share European social structures, legal systems, or religious beliefs were cast as living outside history itself, suspended in a primitive state that justified intervention. Civilization, in this sense, was not merely a description but a standard imposed from above.

Christian theology further reinforced this hierarchy. Conversion had long provided moral justification for expansion, but during the early modern period it became entwined with broader claims about social improvement and moral reform. Salvation and civilization merged into a single project that framed European intervention as a duty rather than an intrusion. To Christianize was to discipline, reorder, and correct, not only souls but entire social worlds. Indigenous spiritual systems were framed not as coherent cosmologies but as superstition, idolatry, or the absence of true belief. This framing denied religious legitimacy to colonized peoples while affirming European authority as divinely sanctioned. Violence undertaken in the name of conversion could thus be narrated as benevolent correction rather than coercion, especially when resistance was interpreted as spiritual obstinacy or moral failure.

Travel literature and early ethnographic writing translated these assumptions into popular understanding. Accounts of the Americas, Africa, and Asia were filtered through European expectations, fears, and ambitions, emphasizing exoticism, danger, and disorder. Authors presented unfamiliar practices as evidence of savagery or moral deficiency, rarely questioning their own interpretive frameworks. These texts circulated widely, shaping public opinion and reinforcing elite ideology. By presenting European observers as neutral witnesses describing inferior worlds, travel narratives naturalized hierarchy and erased the political context of encounter. The repeated portrayal of non-European societies as chaotic, violent, or childlike helped normalize the idea that domination was both necessary and humane, a service rendered to peoples deemed incapable of self governance.

By the seventeenth century, the civilizing narrative had become a flexible ideological tool. It could justify conquest, enslavement, and land seizure while maintaining Europe’s self image as morally superior. Importantly, it did so by recoding violence as improvement and inequality as obligation. This narrative did not arise accidentally from misunderstanding. It was cultivated through philosophy, theology, and print culture, forming a durable framework that would travel with empire and shape how its actions were recorded, taught, and remembered.

Conquest Rewritten as Improvement

As European empires expanded, conquest was rarely described in the language of domination. Instead, it was framed as intervention, reform, or rescue. Territorial seizure became development, and military occupation was recast as the establishment of order. Colonized lands were presented as underused, mismanaged, or wasted, requiring European governance to unlock their potential. This rhetorical shift transformed acts of aggression into projects of improvement and allowed imperial powers to portray themselves as benefactors rather than invaders.

Enslavement and forced labor were similarly redefined. Rather than acknowledged as systems of exploitation, they were justified as forms of discipline or moral training. Colonial administrators and metropolitan commentators argued that labor imposed structure on allegedly idle populations and introduced them to the values of productivity and obedience. In this framework, coercion became instruction. Suffering was dismissed as necessary preparation for participation in a civilized economy, and resistance to forced labor was treated as proof of moral deficiency rather than evidence of injustice.

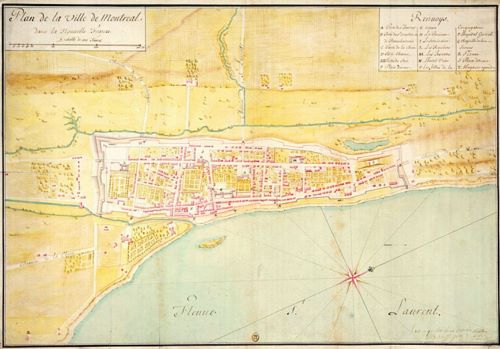

Legal doctrine played a crucial role in sustaining this transformation. European powers developed laws and charters that rendered dispossession lawful while stripping Indigenous peoples of political agency. Concepts such as terra nullius and doctrines of discovery allowed empires to claim lands already inhabited by redefining ownership through European legal standards, effectively erasing Indigenous sovereignty by refusing to recognize it as legally meaningful. Courts, treaties, and administrative decrees translated conquest into paperwork, converting violence into procedure and force into legitimacy. By embedding domination within legal systems, imperial states masked coercion behind the appearance of order and consent, normalizing inequality as a technical matter of governance rather than an outcome of conquest.

The rewriting of conquest as improvement depended on narrative repetition. Official histories, proclamations, and educational texts reinforced the idea that empire brought roads, schools, religion, and governance to societies deemed incapable of achieving them independently. These benefits were presented as outweighing or negating the costs of conquest, creating a moral ledger in which infrastructure and order conveniently canceled dispossession and death. Such narratives functioned to sever cause from effect, celebrating imperial achievements while isolating them from the violence that made them possible. Improvement became the story empire told itself, a story polished through repetition until coercion faded into background noise.

This logic also relied on temporal distancing. Violence was framed as belonging to an unfortunate but necessary past, while the present was presented as orderly, lawful, and benevolent. By emphasizing what empire claimed to have built rather than what it destroyed, colonial narratives invited audiences to judge conquest by its supposed outcomes rather than its methods. This framing insulated imperial power from critique by shifting moral evaluation away from acts of seizure and toward selective visions of progress. In doing so, it taught generations to admire empire for its visible structures while remaining blind to the invisible suffering embedded within them.

Selective Memory and the Architecture of Forgetting

Colonial power did not rely on force alone. It depended equally on the management of memory. Empires understood that domination required a usable past, one that explained conquest without indicting it or destabilizing claims of moral authority. As a result, historical production became an extension of governance rather than a neutral scholarly pursuit. What was recorded, archived, and commemorated was shaped by imperial priorities, while events that threatened the moral coherence of empire were minimized, fragmented, or excluded altogether. Forgetting was not a failure of record keeping or the accidental loss of evidence. It was an outcome carefully produced through institutional practice and narrative control.

Official histories played a central role in this process. Court chroniclers, imperial administrators, and metropolitan historians emphasized exploration, administration, and expansion while treating violence as episodic or incidental. Massacres were reframed as pacification. Uprisings were reduced to disturbances. Entire campaigns of destruction were compressed into vague references to disorder or resistance. By privileging the perspective of the state, these narratives normalized imperial authority and rendered its victims historically marginal. What appeared as an objective account was in fact a deeply curated version of the past.

The archive itself reflected these priorities with striking consistency. Colonial documentation overwhelmingly preserved the voices of officials, missionaries, merchants, and military officers, while Indigenous testimony was excluded, translated through hostile intermediaries, or dismissed as unreliable. Oral histories, ritual memory, and non-European forms of record keeping were rarely treated as legitimate sources, further narrowing what counted as historical evidence. This asymmetry produced a record in which power spoke continuously and the colonized appeared only intermittently, often as objects rather than subjects. The absence of Indigenous perspectives was later treated as evidentiary silence rather than as the result of deliberate exclusion. In this way, archival scarcity became proof of insignificance, reinforcing the very hierarchies that had produced it.

This architecture of forgetting had lasting consequences. Once violence was omitted from the foundational record, later generations encountered a past already stripped of its most destabilizing elements. Selective memory became inherited memory. The result was not ignorance but miseducation, a historical consciousness trained to admire empire without confronting its costs. By shaping what could be known, colonial powers shaped what could be questioned, ensuring that exploitation appeared peripheral while authority remained central.

Education as Imperial Conditioning

Education served as one of the most effective instruments for sustaining imperial ideology. While conquest relied on force, its normalization depended on instruction. Schools did not simply transmit knowledge about empire; they taught students how to feel about it. From an early age, children in imperial centers were introduced to narratives that framed expansion as achievement and governance as generosity. By the time imperial violence entered the classroom at all, it appeared sanitized, abstracted, and morally resolved.

Textbooks played a decisive role in this conditioning. Lessons emphasized explorers, administrators, and reformers while reducing colonized peoples to background figures or obstacles to progress. Imperial figures were portrayed as agents of order and innovation, their actions narrated through achievement rather than consequence. Slavery, when acknowledged, was often described as an unfortunate institution already resolved or as a marginal deviation from an otherwise benevolent imperial project. The brutality of plantation systems, forced labor regimes, and racialized violence was compressed into brief passages or euphemistic language. Resistance movements were stripped of political legitimacy and recast as rebellions against order rather than struggles for autonomy, ensuring that opposition to empire appeared irrational or criminal rather than principled.

Moral education reinforced these lessons by linking empire to virtue. Imperial expansion was framed as a moral obligation, evidence of national maturity and responsibility rather than ambition or greed. Students were encouraged to admire discipline, hierarchy, and governance, values that mirrored imperial administration itself and normalized asymmetrical power. Acts of violence were often presented as regrettable but necessary, reinforcing the idea that moral ends justified coercive means. The suffering of colonized populations was rarely foregrounded because it destabilized this moral framing. To center exploitation would have required confronting the ethical contradictions embedded in imperial identity, a confrontation educational systems were structured to avoid.

The structure of schooling further entrenched these perspectives. Examinations rewarded mastery of imperial chronology and geography without interrogating their human consequences, privileging recall over critical analysis. Maps displayed vast territories shaded in national colors, visually reinforcing possession, permanence, and entitlement. Colonial subjects appeared as statistics, resources, or labor forces rather than as communities with political agency or historical depth. Classroom materials thus transformed empire from a contested and violent process into an inherited fact, something to be memorized rather than questioned.

The long-term effects of this conditioning were profound. Generations emerged with a historical consciousness shaped by omission rather than denial. They did not need to be convinced that empire was good; they had simply never been taught otherwise. This absence of critical engagement ensured that imperial narratives endured beyond the formal end of empire, reproduced in civic memory, public debate, and cultural institutions. Education did not merely reflect imperial ideology. It reproduced it.

Museums as Imperial Storytelling Machines

Museums emerged alongside empire as authoritative spaces for knowledge production, classification, and display. Far from neutral repositories of culture, they functioned as institutional narrators of imperial order. Objects taken from colonized societies were reframed as artifacts of curiosity, artistry, or scientific interest, severed from the conditions under which they were acquired. Violence, coercion, and dispossession were excluded from the story, allowing empire to present itself as a guardian of world culture rather than its destroyer.

The act of display itself carried ideological weight. Cultural materials were arranged to emphasize timelessness and disappearance, suggesting that colonized societies belonged to the past rather than to a contested present. By presenting Indigenous cultures as static or vanishing, museums implicitly justified imperial domination as inevitable and even preservative. Empire appeared not as an agent of disruption but as a steward rescuing fragments of civilization from decline. What was omitted was the role of conquest in producing that very decline.

Anthropology and archaeology lent scholarly authority to these narratives in ways that deeply entwined knowledge production with imperial power. Early practitioners often worked in tandem with colonial administrations, benefiting from access created by military occupation and political control. Excavation, collection, and classification were treated as scientific enterprises governed by objectivity and expertise, masking their dependence on unequal power relations. The removal of objects was framed as rescue or preservation, even when it occurred in contexts of warfare, forced labor, or political repression. By translating coercive acquisition into academic procedure, these disciplines normalized extraction and rendered imperial violence methodologically invisible.

The museum’s silence on violence was not incidental but structural. Acknowledging coercion would have disrupted the aesthetic and moral experience these institutions offered their audiences, challenging the comfort and authority that museums were designed to provide. By isolating objects from histories of enslavement, displacement, and resistance, museums invited admiration without accountability and curiosity without consequence. Visitors could marvel at cultural achievement while remaining insulated from the brutality that made such displays possible. In this way, museums transformed empire into spectacle, converting domination into display and erasure into education, a lesson that taught reverence without reckoning.

Violence without Witness: What Is Not Shown

Imperial narratives did not simply misrepresent violence. They removed it from view. The most consequential feature of colonial memory was not what it displayed but what it refused to show. Absence became a technique of power. By excluding scenes of brutality, coercion, and mass death, imperial institutions ensured that violence remained abstract, distant, and morally weightless. What could not be seen could not easily be judged.

This absence operated through substitution. In place of forced marches, there were maps. In place of enslaved bodies, there were shipping routes, production figures, and economic graphs. In place of massacres, there were dates marking the establishment of order or the suppression of unrest. Violence was translated into administrative language, stripped of sensory and human detail, and redistributed across bureaucratic categories. This transformation allowed empire to be understood as process rather than trauma, as governance rather than harm. By converting suffering into data, imperial systems rendered violence legible only to administrators, not to moral observers.

Museums, textbooks, and public monuments reinforced this logic by foregrounding artifacts and achievements while excluding their conditions of production. Objects appeared without the labor that made them, territories without the blood that secured them, and institutions without the coercion that sustained them. The result was a curated silence that protected audiences from emotional disturbance. Historical understanding was shaped not by lies but by carefully managed incompleteness.

The absence of witness also disrupted moral causality. Without visible suffering, responsibility became diffuse and abstract. Violence appeared accidental, excessive, or exceptional rather than systematic and foundational. Audiences were invited to admire outcomes while remaining disconnected from methods, to celebrate order without confronting the means by which it was imposed. This separation allowed nations to claim heritage without accountability, to inherit prestige without inheriting guilt. Empire could be remembered as productive rather than predatory, successful rather than destructive, precisely because its violence lacked a visible human face.

Importantly, this silence did not erase violence from the lives of those who endured it. It erased it from the consciousness of those who benefited from empire. The asymmetry was deliberate and enduring. Colonized populations carried memory through oral tradition, ritual practice, family history, and lived experience, while metropolitan societies were trained not to see. This divergence ensured that later demands for recognition, restitution, or historical correction could be dismissed as exaggerated, emotional, or insufficiently documented. The absence of witness thus became a weapon, allowing denial to masquerade as skepticism.

Violence without witness became a stabilizing condition of imperial memory. By controlling what was visible, empires controlled what could provoke outrage, empathy, or resistance. The refusal to show was itself an act of power. It ensured that empire could be remembered as civilizing, progressive, and regrettably imperfect rather than as structurally violent. What was not shown did not disappear. It was simply denied an audience.

From Empire to Nation: The Afterlife of Civilizing Myths

The end of formal empire did not bring an end to imperial narratives. As colonial administrations withdrew or collapsed, the stories that had justified expansion were not dismantled or critically reexamined. Instead, they were absorbed into national memory, reshaped to fit new political realities without surrendering their core assumptions. Civilizing myths were repurposed to support identities rooted in heritage, progress, and moral exceptionalism, allowing former imperial powers to narrate continuity rather than rupture. What changed was not the logic of the narrative but its frame. Empire faded from explicit view, while the benefits once attributed to it were quietly claimed as national achievements divorced from their origins in conquest.

Nation states inherited imperial archives, educational systems, and cultural institutions, along with the silences embedded within them. The bureaucratic and intellectual infrastructure of empire did not vanish; it was nationalized. Histories of expansion were rewritten as stories of exploration, trade, and state formation, carefully detached from their colonial context. Violence appeared as episodic or peripheral, confined to distant frontiers or early encounters rather than recognized as structural and enduring. By separating national development from imperial domination, post imperial narratives allowed societies to celebrate their political maturation without confronting the coercive foundations upon which that maturation rested.

Museums and monuments played a central role in this transition. Imperial collections were recontextualized as national treasures, symbols of cultural sophistication rather than conquest. Statues commemorated explorers, settlers, and administrators while ignoring the populations displaced or destroyed in the process. This continuity ensured that imperial authority persisted symbolically, even as political control shifted. The nation inherited not only empire’s objects but its ways of seeing.

Educational reform rarely challenged these inherited frameworks in any fundamental way. While overtly imperial language declined, the underlying narrative structure remained intact, merely softened or reframed. National curricula emphasized unity, progress, and democratic development, often treating colonial violence as an unfortunate but marginal background condition. Empire appeared as a stage that history had moved beyond rather than as a force that actively shaped the nation’s present. Students were encouraged to identify with national ideals without being asked to confront how those ideals were forged through exclusion, extraction, and domination, ensuring that critical historical reckoning remained optional rather than essential.

The afterlife of civilizing myths thus reveals their durability. They survived because they continued to serve a function, protecting collective self image and stabilizing national identity. By transforming imperial violence into national heritage, societies avoided moral reckoning. The past remained usable precisely because it remained incomplete, offering pride without responsibility and memory without accountability.

The Modern Pattern: Sanitizing Slavery and Colonial Violence

Contemporary debates over how slavery and colonialism are presented reveal the persistence of imperial logic under new language. While few now defend empire openly, many institutions continue to manage historical discomfort by reframing violence as marginal, contextual, or excessive to emphasize. Slavery is acknowledged but often cordoned off as an unfortunate chapter rather than recognized as a foundational system. Colonial violence is referenced abstractly, detached from specific actors, policies, and consequences. What emerges is not denial but dilution, a strategy that preserves national self-regard while appearing to engage the past.

Public institutions frequently justify this approach by appealing to balance or neutrality. Exhibits are redesigned to avoid alienating audiences, curricula are softened to prevent controversy, and language is carefully calibrated to reduce emotional impact. Structural exploitation becomes “complex history.” Racialized violence becomes “context.” These rhetorical moves do not clarify the past; they obscure it. The insistence on neutrality masks an ideological choice, one that privileges comfort over clarity and consensus over accountability. By presenting slavery and colonial domination as peripheral rather than constitutive, these narratives repeat the imperial habit of minimizing harm to protect legitimacy, substituting moderation for truth.

Museums and heritage sites illustrate this pattern with particular clarity. Slavery is often confined to discrete rooms, side panels, or temporary exhibitions, separated from broader national narratives of progress and democracy. Colonial extraction may be acknowledged through provenance labels while remaining disconnected from the violence that enabled acquisition. The result is a fragmented moral geography in which suffering is contained and controlled. Visitors are invited to acknowledge injustice without confronting its scale or its centrality to national wealth and power.

Educational controversies reflect similar dynamics. Efforts to expand curricula to include colonial violence or the realities of enslavement are often met with accusations of politicization, divisiveness, or historical pessimism. Calls for accuracy are reframed as ideological intrusion, and educators are pressured to soften language or narrow scope. This reaction reveals the enduring power of civilizing myths. To challenge sanitized narratives is to threaten the moral coherence inherited from empire, a coherence that depends on selective memory. Resistance to such challenges thus becomes a defense of omission rather than a defense of historical rigor, preserving inherited comfort at the expense of truth.

The modern pattern of sanitization matters because it shapes how societies understand responsibility. When slavery and colonial violence are treated as regrettable anomalies rather than structural foundations, demands for reckoning appear excessive or unjustified. History becomes something to be managed rather than confronted. In repeating the colonial strategy of erasure through minimization, contemporary institutions perpetuate the same logic that once justified empire itself: violence must be obscured so the nation can admire itself without guilt.

History as Propaganda, Then and Now

The struggle over colonial memory is not primarily a struggle over facts. It is a struggle over narrative control. Empires understood that domination required not only military and economic power but interpretive authority, the ability to define what events meant and which ones mattered. History became a political instrument, shaping perception as effectively as law or force. What appeared to be objective storytelling was, in practice, ideological work designed to stabilize power and neutralize dissent.

This function of history did not disappear with the end of empire. It adapted. National narratives inherited imperial frameworks and continued to use history to produce coherence, legitimacy, and moral reassurance. The language shifted from civilization to progress, from empire to nationhood, but the underlying purpose remained the same. Violence was reframed as unfortunate necessity, resistance as disruption, and exploitation as complexity. In both contexts, history served less to interrogate power than to justify its outcomes.

Propaganda in this sense does not require falsehood. It relies on emphasis, omission, and framing. By selecting certain events as central and relegating others to the margins, historical narratives guide moral interpretation without overt instruction. When violence is contextualized rather than centered, when suffering is abstracted rather than witnessed, audiences are taught how to feel without being told what to think. This subtlety makes propaganda durable. It survives because it masquerades as balance, restraint, and maturity, presenting itself as the reasonable middle ground between denial and reckoning. In doing so, it renders radical critique excessive and moral clarity naïve, reinforcing the very power structures it claims merely to describe.

Understanding history as propaganda, then and now, exposes why debates over memory provoke such intensity. To challenge inherited narratives is to threaten not only interpretations of the past but identities built upon them. Resistance to historical reckoning is rarely rooted in ignorance alone. It is rooted in the fear that acknowledging violence as foundational would destabilize national innocence and moral self regard. When history ceases to function as reassurance, it becomes unsettling, demanding accountability rather than admiration. In this sense, the politics of memory remain inseparable from the politics of power, and the writing of history remains inseparable from the struggle over who is allowed to speak, whose suffering is acknowledged, and whose lives are rendered visible.

Conclusion: What Civilization Required Us Not to See

Civilization, as it was constructed by early modern empires, depended less on what it revealed than on what it concealed. Its moral authority rested on the systematic removal of violence from view, the careful framing of conquest as benevolence, and the transformation of domination into progress. By controlling narrative, empire did not merely justify its actions. It reshaped the conditions under which judgment itself could occur. What could not be seen, named, or centered could not easily be condemned.

This essay has traced how that logic operated across institutions that claimed neutrality and permanence. Histories curated by imperial states, educational systems designed to cultivate loyalty, and museums structured to invite admiration all worked together to produce a coherent and comforting past. Violence was not denied outright. It was fragmented, minimized, or displaced until it lost explanatory power. The result was not historical ignorance but historical training, a way of knowing that privileged continuity over rupture and achievement over accountability.

The persistence of these patterns into the present demonstrates that civilizing myths were never confined to empire alone. They survived because they remained useful. They allowed nations to inherit the prestige of expansion without inheriting its moral burden. Contemporary efforts to sanitize slavery or colonial violence do not represent a departure from imperial logic but its continuation under democratic language. The impulse to soften, contextualize, or marginalize harm reflects the same fear that once motivated colonial historiography: that confronting violence as foundational would destabilize cherished identities.

What civilization required us not to see was never incidental. It was structural. To recover those absences is not to indulge in pessimism or anachronism. It is to restore causality, responsibility, and human presence to a past long managed for comfort. History ceases to function as propaganda only when it refuses reassurance and insists on reckoning. In that insistence lies the possibility of a more honest inheritance, one that values truth over innocence and memory over myth.

Bibliography

- Adas, Michael. Machines as the Measure of Men: Science, Technology, and Ideologies of Western Dominance. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989.

- Ahlenius, Jason. “Sensation’s Imperial Narratives: Affect in the United States’ Democracy of Print, 1846–1848.” Western American Literature 50:4 (2016): 285-315.

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 1983.

- Appleby, Joyce, Lynn Hunt, and Margaret Jacob. Telling the Truth about History. New York: W. W. Norton, 1994.

- Bennett, Tony. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London: Routledge, 1995.

- Benton, Lauren. A Search for Sovereignty: Law and Geography in European Empires, 1400–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Bernays, Edward. Propaganda. New York: Horace Liveright, 1928.

- Cannadine, David. Ornamentalism: How the British Saw Their Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Césaire, Aimé. Discourse on Colonialism. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1950.

- Coates, Ta-Nehisi. “The Case for Reparations.” The Atlantic, June 2014.

- Coombes, Annie E. Reinventing Africa: Museums, Material Culture and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994.

- Dirks, Nicholas B. The Scandal of Empire: India and the Creation of Imperial Britain. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Herman, Edward S., and Noam Chomsky. Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon Books, 1988.

- Hicks, Dan. The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. London: Pluto Press, 2020.

- Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger, eds. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Loomba, Ania. Colonialism Postcolonialism. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Mbembe, Achille. On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

- Mechkarini, Sara, Dega Siân Rutherford, and Berny Sèbe. “Unmasking the Colonial Past: Memory, Narrative, and Legacy.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 51:5 (2003): 825-841.

- Pagden, Anthony. The Fall of Natural Man: The American Indian and the Origins of Comparative Ethnology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- —-. Lords of All the World: Ideologies of Empire in Spain, Britain and France c.1500–c.1800. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

- Said, Edward W. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Knopf, 1993.

- Scott, James C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Simmons, Kali. “’It Has to Stop”: Refusing Colonial Narratives in The Only Good Indians.” The American Indian Quarterly 47:1 (2023): 70-85.

- Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- —-. Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013.

- Thiong’o, Ngũgĩ wa. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. London: James Currey, 1986.

- Thomas, Nicholas. Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Todorov, Tzvetan. The Conquest of America: The Question of the Other. New York: Harper and Row, 1982.

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel. The Modern World-System I. New York: Academic Press, 1974.

- White, Hayden. The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987.

- Wineburg, Sam. Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone). Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

- Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387–409.

- Young, Robert J. C. Postcolonialism: An Historical Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell, 2001.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.30.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.