The history of presidential emergency powers in the United States reveals a persistent pattern: crises serve as accelerants for executive authority that, once claimed, is rarely relinquished.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The exercise of emergency power has long stood at the uneasy frontier between law and necessity in the American constitutional order. From the earliest days of the republic, presidents have claimed authority to act in moments of crisis beyond what is ordinarily permitted, often invoking the survival of the Union as justification. These moments of expansion, whether Abraham Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War or Franklin Roosevelt’s declaration of a national banking emergency at the height of the Great Depression, raise perennial questions about whether the American presidency is fundamentally bounded by law or whether, in times of peril, necessity knows no law at all.1

The United States Constitution is conspicuously silent on a general grant of emergency powers. While it provides for habeas corpus suspension “in cases of rebellion or invasion,” it contains no broad clause authorizing executive action in times of danger.2 This omission was deliberate: the Framers feared that codifying emergency authority would invite abuse, recalling Roman precedents where temporary dictatorship slipped into tyranny. Yet necessity has consistently intruded. Statutory instruments such as the Insurrection Act of 1807, the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, and later the National Emergencies Act of 1976 have provided presidents with pathways to mobilize extraordinary powers in response to crises.3 At the same time, presidents have often acted without clear statutory basis, relying instead on expansive claims of inherent constitutional authority.

Historians and legal scholars have long debated whether these episodes represent aberrations or enduring shifts in constitutional structure. Clinton Rossiter once argued that “constitutional dictatorship” was an inevitable corollary of democratic survival in crisis.4 Arthur Schlesinger Jr. famously diagnosed an “imperial presidency” in which emergency powers became routine tools of governance.5 More recent scholarship emphasizes the legal frameworks that make such expansions possible, focusing on how Congress has delegated hundreds of emergency authorities to the executive, and how courts have policed, or declined to police, their exercise.6

What follows traces the history of presidential emergency powers in the United States, with special attention to the formal declarations of national emergency that, since 1976, have provided statutory gateways to vast reservoirs of authority. It argues that while the use of emergency powers has evolved from ad hoc acts of necessity to routinized statutory declarations, the underlying pattern has remained consistent: crises serve as accelerants for executive aggrandizement, while mechanisms of rollback prove fragile or ineffective. By examining both the dramatic episodes (Lincoln’s wartime measures, Roosevelt’s banking and war proclamations, Truman’s Korean War emergency) as well as the proliferation of formal emergency declarations from Carter through Trump’s second term, the essay highlights how “emergency governance” has become a near-permanent feature of the American presidency.

Early Republic to Civil War: Precedents and Flexibility

Overview

The Founding generation was acutely aware of the dangers of concentrated power in times of crisis. Unlike many European constitutions that explicitly allowed for extraordinary measures, the U.S. Constitution was written without a general emergency clause. The only express reference comes in Article I, Section 9, permitting the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus “when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.”7 This provision, notably lodged in the legislative article, suggests that Congress, not the president, was intended to wield the suspension power. Yet from the earliest days of the republic, presidents acted on their own initiative in the face of emergencies, laying the groundwork for a pattern of executive flexibility.

Washington and Early Republican Precedent

In 1794, President George Washington personally led militia forces to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania, invoking the Militia Acts passed by Congress.8 While grounded in statute, the episode was significant: it established that the president could unilaterally determine when an “insurrection” existed and act without waiting for prolonged legislative deliberation. The precedent of swift executive response, even when constitutionally tethered to congressional authorization, would echo throughout American history.

Thomas Jefferson similarly pressed the boundaries of presidential initiative. During the Embargo Crisis of 1807, Jefferson relied on broad interpretations of statutory authority to restrict trade and deploy military resources to enforce the embargo against widespread resistance.9 Though unpopular, Jefferson’s actions underscored the willingness of early presidents to treat statutory delegations as capacious grants in times of perceived emergency.

The Insurrection Act of 1807

Congress codified a mechanism for domestic emergencies in the Insurrection Act of 1807, empowering presidents to use the military to suppress rebellion and enforce federal law.10 Though rarely invoked in the antebellum period, the Act would become a recurring instrument of presidential power, linking statutory legitimacy to executive discretion. Its importance lay less in its immediate use and more in establishing a legislative baseline that presidents would invoke in later crises, often stretching its language to meet novel circumstances.

Lincoln and the Civil War

The crucible of presidential emergency powers arrived with Abraham Lincoln. Faced with secession and rebellion in 1861, Lincoln acted decisively before Congress had assembled. He suspended the writ of habeas corpus along critical rail lines, ordered the arrest of suspected Confederate sympathizers, and unilaterally called up the militia and expanded the army.11 In doing so, he claimed powers that went far beyond the Constitution’s explicit text. When Chief Justice Roger Taney, sitting in chambers in Ex parte Merryman (1861), ruled Lincoln’s suspension unconstitutional, the president ignored the decision, citing necessity and his oath to preserve the Union.12

Lincoln defended his actions in a famous message to Congress, asking whether all laws should “but one go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces, lest that one be violated.”13 His reasoning, that necessity justified stretching constitutional boundaries, set a template for future executives. The judiciary eventually imposed limits, most notably in Ex parte Milligan (1866), where the Court ruled that military tribunals could not supplant civilian courts in areas where they remained open.14 Yet by then the precedent had been set: the presidency could, in the name of preserving the Union, suspend liberties and concentrate power in ways the Framers had feared.

Legacy of the Antebellum Period

The early republic through the Civil War demonstrated two patterns. First, emergencies often prompted executive initiative, justified after the fact by Congress or the courts. Second, once claimed, powers were rarely forgotten. Washington’s militia call-outs, Jefferson’s embargo enforcement, and especially Lincoln’s wartime measures all illustrated that crises could expand the presidency’s role as the first responder to national peril. Even in the absence of a formal “national emergency” declaration, as would later exist under the National Emergencies Act, presidents had already established the practice of acting first and defending their choices later.

Early 20th Century: Institutionalization of Emergency Powers

Overview

The turn of the twentieth century marked a new phase in the history of presidential emergency authority. Whereas nineteenth-century presidents had relied primarily on implied constitutional prerogatives or narrow statutory authorizations such as the Insurrection Act, the twentieth century saw the codification and expansion of statutory frameworks designed to be activated in times of national crisis. These delegations created legal reservoirs of executive authority that could be tapped with a declaration of emergency, laying the groundwork for what scholars now call the “modern emergency state.”15

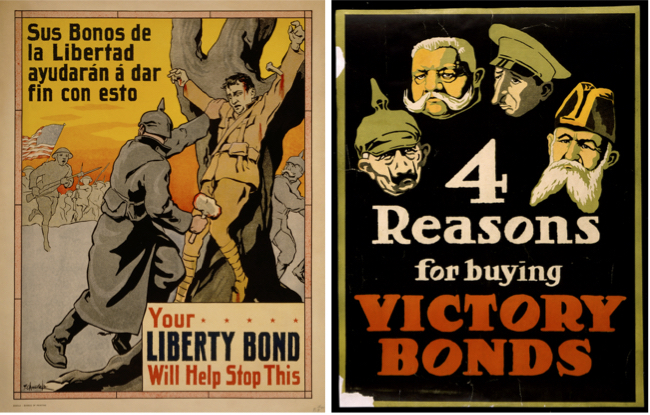

Woodrow Wilson and the First World War

When the United States entered the First World War in April 1917, Congress passed the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA), empowering the president to regulate, license, or prohibit a wide range of economic transactions involving enemy nations.16 Wilson quickly invoked the Act to take control of communications, censor publications, and regulate foreign commerce. For the first time, emergency powers were not improvised but explicitly conferred by statute, with vast discretion left to the executive.

The significance of the TWEA extended beyond wartime. Its broad language allowed subsequent presidents to declare “national emergencies” even in peacetime, using its provisions to regulate the economy and seize foreign assets.17 In effect, Congress had created a standing framework for executive economic emergency powers, one that would be invoked repeatedly throughout the twentieth century.

Franklin Roosevelt and the Great Depression

The most consequential peacetime use of emergency powers came with Franklin Roosevelt’s response to the banking crisis of March 1933. One day after his inauguration, Roosevelt issued Proclamation 2039, declaring a national banking emergency under the TWEA.18 He ordered a four-day “bank holiday” that temporarily shut down the entire financial system. Within days, Congress ratified his actions by passing the Emergency Banking Act, effectively endorsing Roosevelt’s unilateral declaration and extending broad discretionary powers over currency, gold, and financial institutions.19

This was a watershed moment: for the first time in American history, a president had declared a national emergency in peacetime to address a domestic economic crisis. Roosevelt justified his actions in existential terms, describing the situation as equivalent to war.20 His boldness, coupled with Congress’s swift ratification, marked a turning point in how emergencies were conceptualized: no longer confined to rebellion or invasion, they could now encompass systemic economic collapse.

Roosevelt and the Second World War

Even before Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt used emergency proclamations to prepare for global conflict. In September 1939, following Germany’s invasion of Poland, he proclaimed a limited national emergency, expanding military preparedness and economic controls.21 After Pearl Harbor in December 1941, he issued a full declaration of national emergency, unlocking extensive statutory authorities to mobilize industry, ration resources, and regulate nearly every aspect of American economic life.22

The Second World War solidified the institutionalization of emergency government. Administrative agencies proliferated, executive orders multiplied, and the president became the undisputed manager of total war. Civil liberties suffered accordingly, most notoriously in the internment of Japanese Americans authorized by Executive Order 9066, upheld by the Supreme Court in Korematsu v. United States (1944).23 Although the war ended in 1945, many of the emergency measures remained in place, sustaining a legal and institutional apparatus that blurred the line between wartime and peacetime governance.

Legacies of the Early 20th Century

The Wilson and Roosevelt administrations transformed the practice of emergency powers in three ways. First, they expanded the statutory foundation for emergencies, especially in economic matters, through the TWEA and related legislation. Second, they established the legitimacy of peacetime national emergency declarations, particularly Roosevelt’s banking crisis proclamation. Finally, they demonstrated the capacity of crises to create lasting institutional change: agencies and powers born in emergencies often persisted long after the crises subsided. As one Senate investigation later concluded, by mid-century the United States lived in a state of “permanent emergency,” with little distinction between the extraordinary and the ordinary.24

Cold War Era and the Problem of “Permanent Emergency”

Overview

The Second World War did not end the presidency’s reliance on emergency authority. Instead, the Cold War extended and normalized the practice of governing through emergency powers. A legal and institutional framework that had once been conceived as temporary became semi-permanent, blurring the line between ordinary and extraordinary governance.

Truman and the Korean War

President Harry Truman carried Roosevelt’s emergency legacy into the Cold War. In December 1950, following the Chinese intervention in Korea, Truman issued Proclamation 2914, declaring a national emergency.25 This formal declaration, justified by the outbreak of war and threats to global security, unlocked extensive statutory powers. It also inaugurated a new era: for the next quarter century, the United States would live under a continuous state of emergency.

Truman’s use of emergency power soon met judicial resistance. In 1952, he issued Executive Order 10340, seizing control of the steel mills to prevent a labor strike that threatened war production.26 The Supreme Court struck this down in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952), ruling that Truman lacked statutory or constitutional authority.27 Justice Robert Jackson’s concurring opinion, with its tripartite framework for evaluating presidential power, became the canonical test for executive authority in emergencies. Yet the Court did not question the broader practice of declaring emergencies; Truman’s proclamation remained in effect, and emergency government continued.

Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson

Truman’s 1950 proclamation provided a legal umbrella for his successors. Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson governed against the backdrop of the Korean War emergency, invoking its statutory authorities as needed. For example, Johnson’s Vietnam-era escalations rested less on new declarations than on the continuation of Truman’s emergency and congressional resolutions such as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (1964).28

The persistence of Truman’s proclamation illustrates the ease with which emergency authority could be perpetuated without fresh justification. Presidents discovered that so long as an emergency remained technically in effect, they had ready access to broad statutory powers without the political cost of re-declaring a new one.

Nixon and the Expansion of Emergency Governance

By the time Richard Nixon entered office, emergency powers had become deeply woven into the presidency. Nixon invoked them repeatedly, most notably in 1970 when he declared a national emergency in response to domestic economic instability.29 This allowed him to impose wage and price controls, regulate imports, and expand federal intervention in the economy. The declaration added yet another layer to the already thick fabric of ongoing emergencies.

By the early 1970s, the United States was technically governed under four separate national emergencies: Roosevelt’s 1933 banking crisis proclamation, Roosevelt’s 1941 wartime proclamation, Truman’s 1950 Korean War emergency, and Nixon’s 1970 economic emergency.30 These overlapping declarations created a legal environment in which nearly 470 statutory provisions could be activated by the executive branch at will.31 In effect, emergency powers had become permanent.

Congressional Backlash and the Path to Reform

The revelation of this “permanent emergency” state during the Watergate era alarmed lawmakers. A Senate investigation, led by the Special Committee on the Termination of the National Emergency, issued its landmark 1973 report documenting the scope of unchecked executive power.32 The report warned that the United States had drifted into a condition where emergency had ceased to be exceptional and had become the norm.

The Cold War thus marked a paradox: while the judiciary imposed theoretical limits on unilateral executive action in Youngstown, presidents continued to enjoy the practical benefits of perpetual emergencies. It was left to Congress, in the aftermath of Watergate, to attempt a structural reform, leading to the National Emergencies Act of 1976.

Reform and the National Emergencies Act of 1976

Overview

By the early 1970s, it had become clear that the United States was living under what one Senate committee described as a state of “permanent emergency.”³³ Four separate national emergencies, stretching back to Franklin Roosevelt’s 1933 banking proclamation, were still technically active. These overlapping declarations gave the president access to hundreds of statutory powers, ranging from the ability to seize property and regulate trade to control over communications and the military.34 The Watergate scandal and the broader constitutional crisis of executive power provided the final push for reform.

The Senate Investigation

In 1972, the U.S. Senate established the Special Committee on the Termination of the National Emergency, chaired by Senators Frank Church and Charles Mathias. Its investigation culminated in Senate Report 93-549 (1973), a landmark document cataloguing nearly 470 provisions of federal law that could be activated by presidential declaration of emergency.35 The committee concluded that the accumulation of emergency powers, many dating back to the New Deal and World War II, had created a constitutional imbalance. What were once temporary grants of authority had hardened into a default mode of governance.

The report warned that “a failure to terminate these states of emergency has produced, in effect, a permanent state of national emergency, altering the normal functioning of our governmental processes.”36 This finding was startling: the United States, a nation born in reaction to executive tyranny, had drifted into an indefinite regime of emergency rule without explicit public consent.

Congressional Response: The National Emergencies Act

The legislative remedy came in the form of the National Emergencies Act (NEA) of 1976.37 The Act sought to restore constitutional balance by:

- Terminating all existing national emergencies (Roosevelt’s 1933 and 1941, Truman’s 1950, Nixon’s 1970).

- Requiring that all future emergencies be formally declared by the president, published in the Federal Register, and transmitted to Congress.

- Mandating annual renewal of emergencies, thus preventing them from continuing indefinitely by inertia.

- Providing for termination of emergencies by joint resolution of Congress.

In theory, the NEA promised to confine emergencies to genuine, time-bound crises. In practice, however, the Act contained weaknesses. After the Supreme Court’s decision in INS v. Chadha (1983), which struck down the legislative veto, Congress could terminate an emergency only by passing a law subject to presidential veto.38 This effectively meant that once a president declared an emergency, it would remain in place unless two-thirds of both houses of Congress voted to override a veto, a nearly insurmountable hurdle in modern polarized politics.

Consequences of the Reform

The NEA represented both a genuine reform and a missed opportunity. On the one hand, it ended the accumulation of un-terminated emergencies and forced greater transparency by requiring formal declarations and public notice. On the other hand, it entrenched presidential discretion: the decision to declare an emergency, and to renew it each year, remained entirely within the executive’s hands.

Over time, this framework transformed emergencies from extraordinary departures into routine instruments of governance. Presidents discovered that emergencies could be declared for a wide range of policy purposes (foreign sanctions, economic regulation, even immigration control) and then quietly renewed year after year. By the early twenty-first century, dozens of emergency declarations were still active, some dating back decades.39

The reform of 1976 thus paradoxically normalized the very practice it sought to restrain. Emergency powers had been removed from the shadows, but in being codified and routinized, they became a permanent feature of the modern presidency.

Post-1976 Modern Declarations of National Emergency

Overview

The National Emergencies Act of 1976 was designed to restore balance by requiring transparency, periodic review, and formal termination of presidential emergencies. Yet the reform had an unintended effect: it normalized the practice of emergency declarations. Rather than rare, time-bound exceptions, national emergencies became routine tools of presidential governance. Each administration since Jimmy Carter has declared at least one, and many remain in effect decades later.

Jimmy Carter (1979)

The first test of the new framework came with the Iranian hostage crisis. On November 14, 1979, Carter issued Executive Order 12170, declaring a national emergency to freeze Iranian assets in the United States.40 This emergency, renewed annually by subsequent presidents, remains in effect today, making it one of the longest-standing national emergencies in U.S. history.41

Ronald Reagan (1980s)

Reagan used the NEA repeatedly to impose sanctions. He declared national emergencies with respect to South Africa (1985), Nicaragua (1985), and Libya (1986).42 These emergencies, often tied to foreign policy disputes, illustrated how the NEA became a mechanism for imposing economic sanctions without new congressional legislation.

George H. W. Bush (1990–1993)

Bush declared a national emergency with respect to Iraq in August 1990 following its invasion of Kuwait.43 This declaration triggered sweeping economic sanctions and laid the groundwork for U.S. participation in the Gulf War. It also set the precedent for relying on emergency declarations as tools of foreign policy leverage.

Bill Clinton (1993–2001)

Clinton’s presidency was prolific in emergency use, with more than a dozen declarations. They targeted proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, narcotics trafficking, terrorism, and conflicts in the Balkans.44 Many of these emergencies, renewed annually, remain active, underscoring how foreign policy emergencies became semi-permanent features of U.S. governance.

George W. Bush (2001–2009)

The defining emergency of Bush’s presidency followed the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. On September 14, Bush declared a national emergency, activating broad military and homeland security authorities.45 This emergency has been renewed every year since, making it one of the most enduring pillars of U.S. counterterrorism law. Bush also declared additional emergencies related to terrorism financing and proliferation.

Barack Obama (2009–2017)

Obama declared a national emergency in April 2009 in response to the H1N1 influenza outbreak.46 He also issued numerous sanctions-based emergencies, including those targeting Russia, Venezuela, and cyber threats. Like his predecessors, Obama discovered that emergencies provided flexible instruments of foreign policy, many of which were quietly renewed each year with little public scrutiny.

Donald Trump (First Term, 2017–2021)

Trump declared multiple emergencies, most notably:

- 2017: Human rights abuses and corruption (Global Magnitsky Act).47

- 2019: A controversial emergency at the southern border, used to divert military funds for wall construction.48

- 2020: The COVID-19 pandemic, declared a national emergency in March 2020.49

These declarations illustrated the breadth of issues that could be framed as emergencies, from human rights to immigration to public health.

Joe Biden (2021–2025)

Biden extended many of Trump’s declarations while adding new ones, especially sanctions-based emergencies targeting Russia after the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.50 He also managed the winding down of the COVID-19 emergency, which formally ended in May 2023. His presidency confirmed the pattern: emergencies, once declared, tend to persist across administrations regardless of political party.

Donald Trump (Second Term, 2025– )

In his return to office, Trump has used emergency powers with unprecedented frequency. In his first eight months, he declared nine separate national emergencies:

- Southern Border (Jan. 29, 2025) — National emergency at the southern border.51

- National Energy Emergency (EO 14156, Jan. 2025).

- Designation of Cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (Jan. 29, 2025).52

- Northern Border / Illicit Drugs (Feb. 7, 2025).53

- Southern Border Tariffs (EO 14194, Feb. 2025).

- Synthetic Opioid Supply Chain (EO 14195, Feb. 2025).

- Sanctions on the International Criminal Court (EO 14203, spring 2025).

- Executive Order 14257 (July 2025).54

- Brazil (Aug. 5, 2025).55

These declarations range from border security to energy, narcotics, international institutions, and foreign governments. Collectively, they demonstrate how the NEA has evolved from a supposed safeguard into a versatile governing instrument, enabling presidents to restructure economic, foreign, and domestic policy with a single proclamation.

Comparative Reflections and Theoretical Implications

Overview

The historical trajectory of U.S. emergency powers reveals a paradox at the heart of constitutional government. Designed to prevent tyranny through a system of separated powers, the American framework nonetheless has repeatedly enabled presidents to expand their authority in moments of crisis. Each episode, from Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus to Trump’s recent flurry of declarations, demonstrates that emergency powers, once claimed, tend to persist, accumulating into a body of precedent and statutory practice that blurs the line between emergency and ordinary governance.

Comparative Perspective

The American experience is not unique. Parliamentary democracies such as the United Kingdom, France, and India also provide executives with special powers during emergencies, often through statutory instruments.56 Yet key differences emerge. In many systems, legislative oversight is more robust, with requirements for periodic parliamentary reauthorization or strict temporal limits. Germany’s Basic Law, for example, permits emergency measures but embeds detailed procedural safeguards to prevent permanent distortion of democratic governance.57 The United States, by contrast, has created a system where emergencies can be renewed indefinitely, and congressional termination is politically improbable after INS v. Chadha (1983) removed the legislative veto.58

This comparative lens underscores how institutional design shapes outcomes. Where legislatures must periodically reapprove emergencies, executives face constraints; where the default is automatic renewal absent supermajoritarian resistance, as in the United States, emergencies endure.

Theoretical Takeaways

The American pattern suggests three key insights about executive power under stress:

- Crises as Accelerants. Emergencies act as catalysts for executive aggrandizement, enabling presidents to claim new powers or broaden statutory delegations. Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Bush each leveraged crisis to reshape the presidency’s institutional role.

- Path Dependence. Once established, emergency authorities rarely disappear. Roosevelt’s banking proclamation persisted until 1976; Carter’s Iran emergency remains active in 2025; Bush’s post-9/11 emergency continues to be renewed annually. Powers become normalized through repetition.

- The Fragility of Norms. Formal law matters, but so too do norms of restraint. Truman’s steel seizure was blocked in Youngstown, but subsequent presidents learned to ground emergency claims in statutory delegations, avoiding direct judicial confrontation. The result is a presidency that adapts to legal limits by exploiting statutory flexibility.

Future Risks

The twenty-first century raises new challenges for emergency governance. Emerging crises such as climate change, cyber warfare, pandemics, and artificial intelligence do not fit neatly into traditional categories of “rebellion” or “invasion,” yet they may provoke future presidents to declare expansive emergencies. Trump’s second-term use of the NEA to address border security, narcotics, and even relations with Brazil illustrates how the definition of “emergency” can expand to cover a wide spectrum of political priorities.

The danger lies in the erosion of distinction between ordinary and extraordinary law. As emergencies multiply and persist, they risk becoming the default mode of governance. The Framers feared standing armies and permanent war powers; today, the equivalent may be a presidency permanently armed with statutory emergency authorities, quietly renewed each year without meaningful congressional oversight. The central theoretical question is whether the republic can sustain the exceptional as permanent without fundamentally altering its constitutional character.

Conclusion

The history of presidential emergency powers in the United States reveals a persistent pattern: crises serve as accelerants for executive authority, and once powers are claimed, they are rarely relinquished. From Washington’s militia call-ups and Jefferson’s embargo enforcement to Lincoln’s wartime suspension of habeas corpus, early presidents established the precedent that necessity could justify rapid executive initiative. The twentieth century institutionalized this practice, as Congress supplied broad statutory delegations such as the Trading with the Enemy Act and the Insurrection Act. Roosevelt’s banking crisis declaration and wartime proclamations, Truman’s Korean War emergency, and Nixon’s economic emergency each entrenched the presidency as the nation’s first responder to peril.

The National Emergencies Act of 1976 sought to check this trend, but in practice it normalized and routinized emergency declarations. Each president since Carter has declared national emergencies, many of which persist decades after their original justification has faded. Sanctions regimes, counterterrorism frameworks, and foreign policy tools operate under emergencies renewed annually, often with little public debate. The law that was meant to restore constitutional equilibrium has instead ensured that extraordinary powers remain continually available.

Trump’s second term illustrates the culmination of this trend. In less than a year, he declared nine distinct national emergencies, ranging from border security and drug trafficking to sanctions against international institutions and foreign governments. His actions underscore how the definition of “emergency” has expanded to encompass routine policy disputes, converting the exceptional into the ordinary. In this sense, Trump has not broken with historical precedent but extended its logic: emergencies are no longer rare events but standard features of presidential governance.

The implications are profound. The Framers, wary of concentrated power, deliberately avoided granting the executive a general emergency clause. Yet through practice, statute, and precedent, such a clause has emerged in fact if not in text. Emergencies that once required congressional ratification now operate by presidential renewal. Courts, wary of overstepping into political questions, have largely confined their interventions to limiting the most blatant abuses, as in Youngstown. Congress, constrained by the Supreme Court’s elimination of the legislative veto, lacks effective tools to terminate emergencies. The result is a presidency that increasingly governs through a standing reservoir of statutory authority.

Whether the republic can sustain this blurring of the extraordinary into the ordinary remains an open question. Comparative examples suggest that democracies risk eroding their constitutional foundations when emergency governance becomes permanent. In the United States, the danger lies not in a sudden descent into dictatorship but in the gradual accretion of emergency powers that alter the balance of separated powers. The history of presidential emergency powers, from Lincoln to Trump, demonstrates the fragility of constitutional restraints in the face of necessity. The challenge for the future is whether those restraints can be revitalized before emergency becomes indistinguishable from the norm.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Clinton Rossiter, Constitutional Dictatorship: Crisis Government in the Modern Democracies (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1948).

- U.S. Const., art. I, sec. 9, cl. 2.

- “Insurrection Act of 1807,” U.S. Code, Title 10, §§ 251–255; “Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917,” 40 Stat. 411; “National Emergencies Act of 1976,” Pub. L. No. 94-412, 90 Stat. 1255.

- Rossiter, Constitutional Dictatorship, 5–6.

- Arthur Schlesinger Jr., The Imperial Presidency (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973).

- Brennan Center for Justice, A Guide to Emergency Powers and Their Use (New York: 2019); David Landau, “Rethinking the Federal Emergency Powers Regime,” Ohio State Law Journal 84 (2018): 603–76.

- U.S. Const., art. I, sec. 9, cl. 2.

- Richard H. Kohn, Eagle and Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the Military Establishment in America, 1783–1802 (New York: Free Press, 1975), 205–12.

- Leonard W. Levy, Jefferson and Civil Liberties: The Darker Side (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963), 83–97.

- “Insurrection Act of 1807,” U.S. Code, Title 10, §§ 251–255.

- James G. Randall, Constitutional Problems under Lincoln (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1926), 118–32.

- Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861).

- Abraham Lincoln, “Message to Congress in Special Session,” July 4, 1861, in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 4:421.

- Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. (4 Wall.) 2 (1866).

- Daniel Farber, Lincoln’s Constitution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 185–87.

- Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, Pub. L. No. 65-91, 40 Stat. 411.

- Jules Lobel, “Emergency Power and the Decline of Liberalism,” Yale Law Journal 98, no. 7 (1989): 1389–90.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, Proclamation 2039, March 6, 1933, in Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, vol. 2 (New York: Random House, 1938), 67–68.

- Emergency Banking Act of 1933, Pub. L. No. 73-1, 48 Stat. 1.

- Roosevelt, First Fireside Chat, March 12, 1933, in Public Papers and Addresses, vol. 2, 75.

- Roosevelt, Proclamation 2352, September 8, 1939, Federal Register 4 (1939): 3851.

- Roosevelt, Proclamation 2487, December 8, 1941, Federal Register 6 (1941): 6367.

- Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944).

- Senate Report 93-549, Emergency Powers Statutes: Report of the Special Committee on the Termination of the National Emergency (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1973).

- Proclamation 2914, “Proclaiming the Existence of a National Emergency,” December 16, 1950, Federal Register 15 (1950): 9029.

- Exec. Order No. 10340, “Directing the Secretary of Commerce to Take Possession of and Operate the Steel Mills,” April 8, 1952.

- Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952).

- Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, Pub. L. No. 88-408, 78 Stat. 384 (1964).

- Proclamation 4074, “Declaring a National Emergency,” August 15, 1971, Federal Register 36 (1971): 15727.

- Senate Report 93-549, 4–5.

- Ibid., 6–7.

- Ibid., 1–10.

- Senate Report 93-549, 1.

- Ibid., 6–7.

- Ibid., 12–18.

- Ibid., 2.

- National Emergencies Act of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-412, 90 Stat. 1255.

- Immigration and Naturalization Service v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983).

- Brennan Center for Justice, Guide to Emergency Powers, 4–6.

- Exec. Order No. 12170, “Blocking Iranian Government Property,” Nov. 14, 1979.

- Brennan Center, Guide to Emergency Powers, 4.

- Ronald Reagan, Proclamations and Executive Orders, 1985–1986, Federal Register.

- Proclamation 6130, “National Emergency With Respect to Iraq,” Aug. 2, 1990.

- William J. Clinton, Public Papers of the Presidents, 1990s vols.

- Proclamation 7463, “National Emergency by Reason of Certain Terrorist Attacks,” Sept. 14, 2001.

- Exec. Order No. 13507, “Establishing an Emergency Response Council for H1N1,” April 2009.

- Exec. Order No. 13818, “Blocking the Property of Persons Involved in Serious Human Rights Abuse or Corruption,” Dec. 20, 2017.

- Proclamation 9844, “Declaring a National Emergency Concerning the Southern Border,” Feb. 15, 2019.

- Proclamation 9994, “Declaring a National Emergency Concerning the Novel Coronavirus,” Mar. 13, 2020.

- Exec. Order No. 14065, “Blocking Property of Certain Persons in Connection with the Situation in Ukraine,” Feb. 21, 2022.

- Federal Register 2025-01948, “Declaring a National Emergency at the Southern Border of the United States,” Jan. 29, 2025.

- Federal Register 2025-02004, “Designating Cartels and Other Organizations as Foreign Terrorist Organizations,” Jan. 29, 2025.

- Federal Register 2025-02406, “Imposing Duties to Address the Flow of Illicit Drugs Across Our Northern Border,” Feb. 7, 2025.

- Federal Register 2025-06063, EO 14257, July 2025.

- Federal Register 2025-14896, “Addressing Threats to the United States by the Government of Brazil,” Aug. 5, 2025.

- Kim Lane Scheppele, “Law in a Time of Emergency: States of Exception and the Temptations of 9/11,” University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law 6 (2004): 1001–83.

- Donald P. Kommers and Russell A. Miller, The Constitutional Jurisprudence of the Federal Republic of Germany, 3rd ed. (Durham: Duke University Press, 1989), 155–65.

- INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983).

Bibliography

- Basler, Roy P., ed. Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1953.

- Brennan Center for Justice. A Guide to Emergency Powers and Their Use. New York: 2018.

- Clinton, William J. Public Papers of the Presidents. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1990s vols.

- Emergency Banking Act of 1933, Pub. L. No. 73-1, 48 Stat. 1.

- Exec. Order No. 10340, “Directing the Secretary of Commerce to Take Possession of and Operate the Steel Mills,” April 8, 1952.

- Exec. Order No. 12170, “Blocking Iranian Government Property,” November 14, 1979.

- Exec. Order No. 13507, “Establishing an Emergency Response Council for H1N1,” April 2009.

- Exec. Order No. 13818, “Blocking the Property of Persons Involved in Serious Human Rights Abuse or Corruption,” December 20, 2017.

- Exec. Order No. 14065, “Blocking Property of Certain Persons in Connection with the Situation in Ukraine,” February 21, 2022.

- Exec. Order No. 14156, “Declaring National Energy Emergency,” January 2025.

- Exec. Order No. 14194, “Imposing Duties to Address the Situation at Our Southern Border,” February 2025.

- Exec. Order No. 14195, “Imposing Duties to Address the Synthetic Opioid Supply Chain,” February 2025.

- Exec. Order No. 14203, “Imposing Sanctions on the International Criminal Court,” 2025.

- Exec. Order No. 14257, July 2025. Federal Register 2025-06063.

- Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861).

- Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. (4 Wall.) 2 (1866).

- Farber, Daniel. Lincoln’s Constitution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt. Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt. New York: Random House, 1938.

- Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, Pub. L. No. 88-408, 78 Stat. 384 (1964).

- Jefferson, Thomas. In Leonard W. Levy, Jefferson and Civil Liberties: The Darker Side. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963.

- Kommers, Donald P., and Russell A. Miller. The Constitutional Jurisprudence of the Federal Republic of Germany. 3rd ed. Durham: Duke University Press, 1989.

- Kohn, Richard H. Eagle and Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the Military Establishment in America, 1783–1802. New York: Free Press, 1975.

- Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944).

- Landau, David. “Rethinking the Federal Emergency Powers Regime.” Ohio State Law Journal 84 (2023): 603–76.

- Levy, Leonard W. Jefferson and Civil Liberties: The Darker Side. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963.

- Lobel, Jules. “Emergency Power and the Decline of Liberalism.” Yale Law Journal 98, no. 7 (1989): 1389–1432.

- National Emergencies Act of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-412, 90 Stat. 1255.

- Proclamation 2039, March 6, 1933. Federal Register.

- Proclamation 2352, September 8, 1939. Federal Register 4 (1939): 3851.

- Proclamation 2487, December 8, 1941. Federal Register 6 (1941): 6367.

- Proclamation 2914, “Proclaiming the Existence of a National Emergency,” December 16, 1950. Federal Register 15 (1950): 9029.

- Proclamation 4074, “Declaring a National Emergency,” August 15, 1971. Federal Register 36 (1971): 15727.

- Proclamation 6130, “National Emergency With Respect to Iraq,” August 2, 1990.

- Proclamation 7463, “National Emergency by Reason of Certain Terrorist Attacks,” September 14, 2001.

- Proclamation 9844, “Declaring a National Emergency Concerning the Southern Border,” February 15, 2019.

- Proclamation 9994, “Declaring a National Emergency Concerning the Novel Coronavirus,” March 13, 2020.

- Public Papers of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Fireside Chat, March 12, 1933.

- Randall, James G. Constitutional Problems under Lincoln. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1926.

- Reagan, Ronald. Proclamations and Executive Orders, 1985–1986. Federal Register.

- Rossiter, Clinton. Constitutional Dictatorship: Crisis Government in the Modern Democracies. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1948.

- Scheppele, Kim Lane. “Law in a Time of Emergency: States of Exception and the Temptations of 9/11.” University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law 6 (2004): 1001–83.

- Schlesinger, Arthur Jr. The Imperial Presidency. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973.

- Senate Report 93-549. Emergency Powers Statutes: Report of the Special Committee on the Termination of the National Emergency. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1973.

- Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, Pub. L. No. 65-91, 40 Stat. 411.

- U.S. Const. art. I, sec. 9, cl. 2.

- Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952).

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.29.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.