Opposition to vaccination arose in a period marked by genuine medical uncertainty, uneven standards of evidence, and expanding state authority over private life.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Vaccination and the Problem of Authority

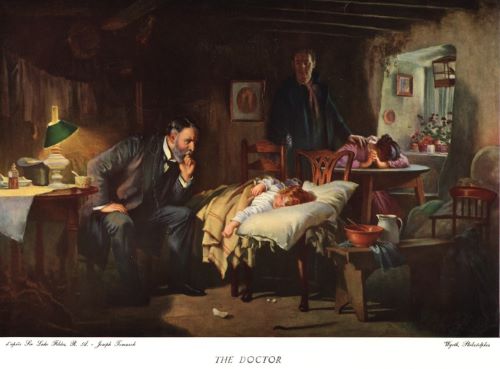

The introduction of vaccination against smallpox at the turn of the nineteenth century marked one of the most consequential interventions in the history of medicine. It promised protection against a devastating disease that had shaped demography, warfare, and daily life for centuries. Yet vaccination did not enter a settled scientific or political landscape. It emerged in a world where medical theory remained contested, clinical standards were uneven, and the authority of the state over individual bodies was still deeply negotiable. From the beginning, vaccination raised questions not only about efficacy and safety, but about who possessed the right to decide what risks were acceptable in the name of public health.

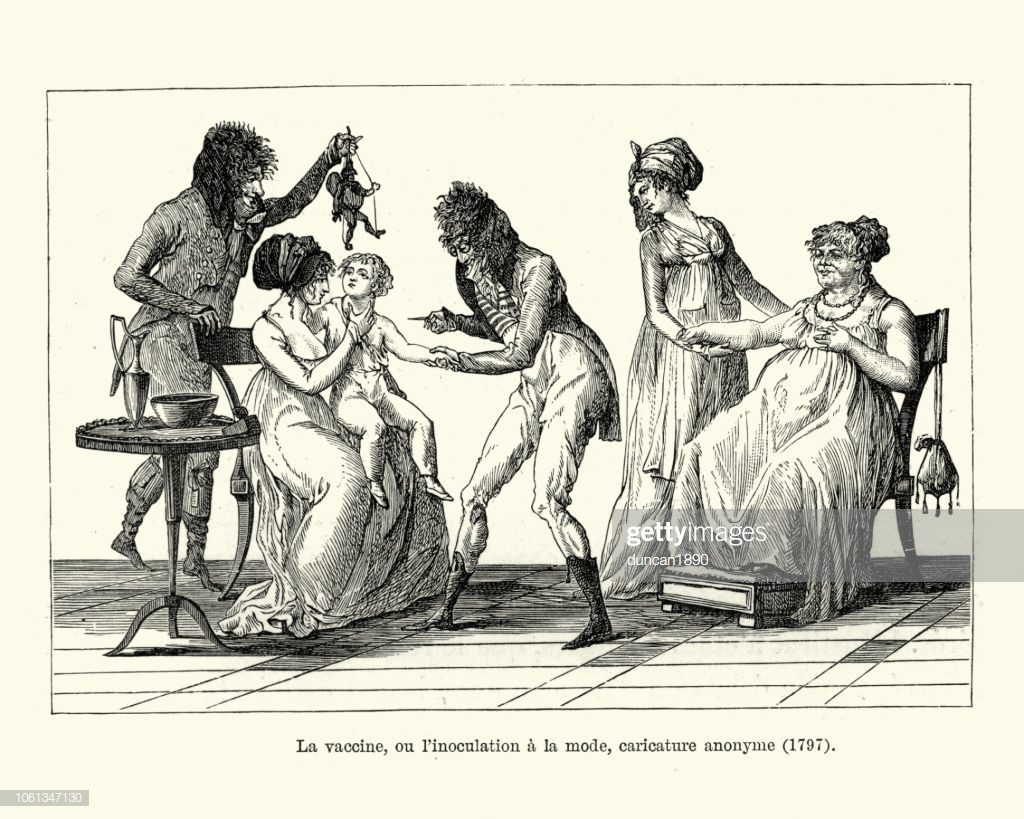

Nineteenth-century opposition to vaccination is often reduced to ignorance or irrational fear, but such portrayals obscure the intellectual and social complexity of the movement. Early vaccination campaigns were conducted before the development of germ theory, standardized production methods, or modern clinical trials. Vaccines varied in quality, adverse reactions were real, and medical consensus was far from uniform. Skepticism toward vaccination therefore arose within a context of genuine uncertainty, shaped by personal experience, statistical dispute, and competing explanations of disease causation.

Resistance intensified as vaccination shifted from recommendation to compulsion. Laws mandating vaccination transformed a medical intervention into an instrument of state power, enforced through fines, penalties, and social pressure. For many critics, the issue was not simply whether vaccination worked, but whether governments and medical authorities could legitimately override individual judgment in matters of bodily integrity. Vaccination became a flashpoint for broader anxieties about consent, liberty, and the expanding reach of bureaucratic governance in an industrializing society.

What follows examines prominent nineteenth-century opponents of vaccination not to rehabilitate their conclusions, but to understand their reasoning. Figures drawn from science, medicine, religion, and political activism articulated objections that reflected the limits of contemporary knowledge and the contested nature of authority itself. By situating their arguments within their historical context, it becomes possible to see anti-vaccinationism not as a rejection of reason, but as a form of dissent shaped by uncertainty, experience, and competing visions of health and freedom.

The Medical Landscape of the Nineteenth Century

Vaccination entered a medical world that lacked the conceptual and institutional coherence often assumed in retrospect. Early nineteenth-century medicine was a pluralistic field in which competing theories of disease causation coexisted uneasily. Humoral explanations, environmental theories of miasma, contagionist models, and emerging pathological anatomy all offered partial and often contradictory accounts of illness. Physicians disagreed not only about the mechanisms of disease but about appropriate standards of evidence, the interpretation of statistics, and the relationship between prevention and cure.

Smallpox prevention itself reflected this uncertainty. Variolation, the deliberate introduction of smallpox matter to induce immunity, had been practiced for decades before the advent of vaccination and remained in use well into the nineteenth century. Although vaccination using cowpox promised a safer alternative, early methods were inconsistent. Vaccine material was frequently transferred arm-to-arm, raising concerns about contamination and the transmission of other diseases. Storage, dosage, and purity varied widely, and adverse reactions, including severe illness and death, were documented. These realities complicated claims of universal safety and fueled legitimate professional debate.

Medical authority during this period was also fragmented. Licensing standards were uneven, professional organizations were still consolidating, and the distinction between trained physicians and other medical practitioners remained porous. Public confidence in medicine was therefore limited and often localized. Many families relied on personal experience, community knowledge, and alternative practitioners when making health decisions. In this environment, skepticism toward a new intervention imposed from above did not require rejection of medicine itself; it could arise from distrust of particular methods, institutions, or claims of certainty.

The absence of germ theory further constrained how vaccination could be understood and defended. Without a clear explanation of how immunity worked, proponents relied heavily on empirical observation and statistical comparison. Critics challenged these statistics, arguing that declines in smallpox mortality could be attributed to improved sanitation, nutrition, or isolation practices rather than vaccination alone. Disputes over evidence were therefore not peripheral but central to nineteenth-century vaccination debates. Opposition emerged within a medical culture still struggling to define what counted as reliable knowledge.

Compulsory Vaccination and the Rise of Organized Resistance

The transition from voluntary vaccination to compulsory vaccination marked a turning point in nineteenth-century public health. What had begun as a medical recommendation increasingly became a legal obligation, enforced by the power of the state. In Britain, a series of Vaccination Acts beginning in the mid-nineteenth century required parents to vaccinate their children against smallpox, with penalties imposed for noncompliance. This shift altered the nature of opposition. Medical skepticism was transformed into political resistance as vaccination became inseparable from questions of law, coercion, and citizenship.

Compulsion sharpened existing anxieties about bodily autonomy. For many families, vaccination was no longer a matter of private judgment but a requirement enforced through fines, court summonses, and, in some cases, imprisonment. These measures were often applied unevenly, falling most heavily on working-class families who lacked the resources to contest penalties. As enforcement intensified, resentment grew, particularly where vaccination was perceived as unsafe, ineffective, or administered without consent. Resistance became less about individual preference and more about collective grievance.

Organized opposition emerged rapidly in response to these policies. Anti-vaccination leagues, societies, and journals formed to coordinate protest, disseminate information, and challenge official narratives. These organizations framed their objections in the language of civil liberties, parental rights, and constitutional restraint. Vaccination was portrayed not merely as a medical procedure but as a test case for the limits of state authority over private life. The rhetoric of resistance drew on liberal traditions that emphasized consent as the foundation of legitimate governance.

Public demonstrations gave visible form to this opposition. Large rallies and marches, particularly in industrial towns, protested compulsory vaccination laws and their enforcement. Protesters carried banners, distributed pamphlets, and invoked historical struggles for political rights. These gatherings reveal that anti-vaccinationism was not a marginal phenomenon confined to isolated individuals, but a mass movement capable of mobilizing thousands. The scale of protest reflected the depth of feeling provoked by compulsory health measures in an era of expanding state intervention.

Legal challenges became another arena of resistance. Opponents pursued court cases to contest fines, question enforcement practices, and expose perceived injustices. While many challenges failed, they kept vaccination controversies in the public eye and forced governments to defend their policies repeatedly. Over time, sustained resistance contributed to legislative modification rather than outright repeal. Conscientious objection clauses were introduced, acknowledging that compulsion without accommodation risked undermining public trust.

The rise of organized resistance underscores a central feature of nineteenth-century anti-vaccinationism: it was fundamentally shaped by the relationship between medicine and power. Opposition hardened not simply because vaccination existed, but because it was imposed. The movement drew strength from the belief that medical authority, when fused with legal coercion, required scrutiny and restraint. In this sense, organized resistance reflected broader struggles over governance, rights, and the boundaries of expertise in a rapidly modernizing society.

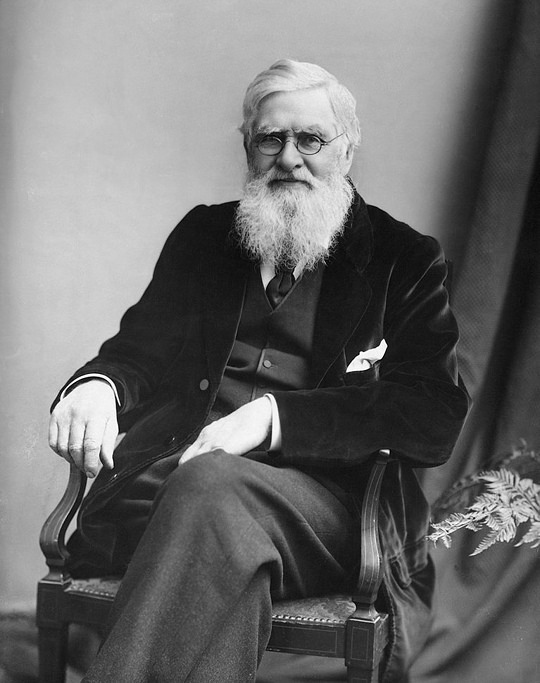

Alfred Russel Wallace: Evolution, Natural Law, and Skepticism of Vaccination

Among nineteenth-century opponents of vaccination, Alfred Russel Wallace occupies a singular position. As the co-discoverer of natural selection, Wallace was not a marginal figure operating outside scientific culture, but a respected naturalist deeply engaged with questions of evidence, causation, and social reform. His opposition to vaccination therefore carried particular weight and provoked discomfort among contemporaries who assumed that scientific authority naturally aligned with public health policy. Wallace’s dissent illustrates how resistance to vaccination could emerge from within, rather than against, scientific reasoning as it was understood at the time.

Wallace’s skepticism rested heavily on statistical critique. He challenged official mortality figures used to demonstrate the success of vaccination, arguing that they were selectively presented and methodologically flawed. According to Wallace, declines in smallpox mortality correlated more closely with improvements in sanitation, nutrition, and living conditions than with vaccination alone. He insisted that population-level statistics failed to account for confounding variables and that causation was being asserted where correlation had not been rigorously established. In this respect, Wallace saw himself as defending scientific rigor against what he perceived as administrative overreach.

Underlying these statistical arguments was a broader philosophical commitment to natural law. Wallace believed that health was best preserved through environmental reform rather than artificial intervention. Clean water, adequate housing, and proper nutrition aligned with evolutionary principles and respected the body’s adaptive capacities. Vaccination, by contrast, appeared to him as an unnatural intrusion that bypassed these systemic improvements. This perspective did not reject science, but prioritized ecological and social explanations over biomedical ones, reflecting tensions within nineteenth-century thought about how nature operated and how humans should intervene in it.

Wallace also objected to compulsory vaccination on moral and political grounds. He viewed state-enforced medical procedures as violations of personal liberty and parental responsibility. For Wallace, scientific uncertainty combined with coercion represented a dangerous convergence. His critique was not that vaccination was inherently malicious, but that it was insufficiently proven to justify compulsion. In articulating this position, Wallace exemplified a form of dissent that blended scientific skepticism, social reform, and liberal political philosophy. His case demonstrates that nineteenth-century anti-vaccinationism cannot be dismissed as anti-scientific reflex but must be understood as part of a broader debate over evidence, authority, and the limits of state power.

William Tebb and the Moral Case Against Compulsion

William Tebb approached vaccination not primarily as a technical medical issue, but as a moral and humanitarian one. Unlike critics who focused on statistical disputes or theoretical explanations of disease, Tebb centered his opposition on the human cost of compulsory vaccination. He was deeply involved in the organized anti-vaccination movement and became one of its most visible public advocates, using pamphlets, lectures, and political agitation to challenge what he saw as an unjust exercise of state power over individual bodies.

Central to Tebb’s argument was the claim that compulsory vaccination violated fundamental principles of consent and parental responsibility. He documented cases of children who suffered injury or death following vaccination, presenting these incidents as evidence that the state was willing to sacrifice individual lives for abstract population-level benefits. Whether or not such cases represented broader trends, they carried enormous rhetorical force. Tebb argued that no government had the moral right to impose medical risk on unwilling subjects, particularly when those subjects were children incapable of consent.

Tebb also framed vaccination policy as a failure of humanitarian ethics. He criticized public health authorities for prioritizing statistical outcomes over lived experience, accusing them of treating human suffering as collateral damage. In his writings, he contrasted the coercive enforcement of vaccination with alternative approaches focused on sanitation, nutrition, and poverty reduction. These reforms, he argued, addressed the root causes of disease without violating personal liberty. Vaccination, by comparison, appeared to him as a shortcut that ignored social responsibility in favor of bureaucratic efficiency.

The moral language of Tebb’s critique resonated widely and helped sustain organized resistance over decades. By shifting the debate away from purely medical expertise and toward questions of justice, conscience, and state violence, he broadened the appeal of anti-vaccination activism. His arguments reveal how opposition to vaccination could function as a form of ethical protest rather than scientific denial. In Tebb’s case, the fight against compulsory vaccination was inseparable from a broader vision of civil liberty, humanitarian reform, and skepticism toward centralized authority.

Medical Critics: Benjamin Moseley and William Rowley

Opposition to vaccination in the nineteenth century did not come solely from political activists or social reformers. Some of the earliest and most influential criticism originated within the medical profession itself. Physicians such as Benjamin Moseley and William Rowley articulated objections grounded in clinical observation, professional rivalry, and concern over unintended consequences. Their critiques reveal that vaccination was not universally accepted even among trained practitioners and that early medical dissent played a significant role in shaping public skepticism.

Benjamin Moseley emerged as a vocal critic of cowpox vaccination shortly after its introduction. As a physician with experience treating smallpox, Moseley questioned whether immunity derived from an animal disease could be safely transferred to humans. He warned that vaccination might introduce new pathologies rather than prevent existing ones, citing cases in which vaccinated individuals developed severe reactions. Moseley’s arguments reflected prevailing anxieties about contamination, bodily purity, and the limits of medical intervention in an era before microbiological understanding.

Moseley also expressed concern about the erosion of professional judgment. He argued that vaccination was being promoted as a universal remedy without sufficient regard for individual constitution or circumstance. In his view, the rapid institutionalization of vaccination discouraged careful clinical evaluation and encouraged mechanical application. This critique aligned with broader tensions within medicine over standardization, authority, and the role of experience versus theory. Moseley feared that enthusiasm for vaccination was outrunning evidence, a charge that resonated with practitioners wary of medical fashion.

William Rowley advanced similar objections but placed greater emphasis on procedural risk. He focused on the methods used to propagate vaccine material, particularly arm-to-arm transmission, which he believed carried a serious danger of spreading other diseases. Rowley documented cases in which vaccination appeared to coincide with the onset of unrelated illnesses, arguing that the procedure lacked sufficient safeguards. Although modern medicine would later address many of these concerns through improved production and sterilization, they were credible anxieties in the context of nineteenth-century practice.

Rowley also challenged claims of vaccine efficacy by scrutinizing reported outcomes. He argued that proponents overstated success while minimizing failure, especially in cases where vaccinated individuals still contracted smallpox. These observations fueled debates over whether vaccination provided absolute protection or merely reduced severity. For Rowley, such uncertainty undermined the justification for compulsory vaccination and called into question the ethical legitimacy of enforcing a procedure whose benefits were not uniformly demonstrable.

Moseley and Rowley exemplify a form of medical dissent rooted in professional caution rather than ideological opposition. Their critiques did not deny the possibility that vaccination might offer benefit, but they resisted its elevation to unquestioned orthodoxy. By articulating concerns about safety, evidence, and clinical judgment, they contributed to a climate in which vaccination remained contested for decades. Their arguments underscore the extent to which nineteenth-century anti-vaccinationism was shaped by internal medical debate as much as by popular resistance.

Popular and Religious Resistance: John Gibbs and Charles M. Higgins

Opposition to vaccination in the nineteenth century was not confined to scientists, physicians, or political activists. It also found expression among popular writers and religious thinkers who framed vaccination as a moral, spiritual, and social threat. Figures such as John Gibbs and Charles M. Higgins articulated resistance that drew heavily on religious belief, natural theology, and distrust of medical authority. Their arguments circulated widely through pamphlets, sermons, and public lectures, reaching audiences often untouched by professional medical debate.

John Gibbs grounded his opposition to vaccination in a theological understanding of the human body as divinely ordered. He argued that disease and health operated according to moral and spiritual laws established by God, not merely physical mechanisms subject to technical manipulation. Vaccination, in this view, represented an artificial interference with divine design. Gibbs maintained that introducing animal matter into the human body violated natural boundaries and undermined the spiritual integrity of the person. His critique resonated with religious communities wary of modern medicine’s growing claims over life and death.

Gibbs also appealed to parental responsibility as a sacred duty. He framed compulsory vaccination as an infringement not only on civil liberty but on religious conscience, arguing that parents were morally accountable for protecting their children from harm, including harm imposed by the state. This language transformed resistance into an act of faith rather than defiance. For adherents of this view, refusal to vaccinate was not neglect but obedience to a higher moral law.

Charles M. Higgins advanced a related but more socially oriented critique. While also influenced by religious ideas, Higgins emphasized the moral consequences of state-enforced medicine for working-class families. He portrayed compulsory vaccination as a form of institutional violence disproportionately affecting the poor, who lacked the resources to resist fines or legal penalties. Higgins argued that public health policy masked social injustice, treating symptoms while ignoring the conditions of poverty, overcrowding, and poor sanitation that fostered disease.

Gibbs and Higgins demonstrate how anti-vaccination sentiment could flourish outside elite scientific discourse. Their arguments blended theology, moral reasoning, and social critique, appealing to audiences who experienced vaccination not as a neutral medical intervention but as an imposed moral choice. Popular and religious resistance sustained the movement by grounding it in everyday experience and ethical conviction. This strand of opposition reminds us that vaccination debates were fought not only in laboratories and legislatures, but in churches, homes, and public meeting halls.

John Pitcairn Jr. and Elite Patronage of Anti-Vaccination Movements

Opposition to vaccination in the nineteenth century was not solely a grassroots phenomenon rooted in popular protest or religious conviction. It also attracted support from wealthy and influential figures who possessed the means to sustain organized resistance over time. John Pitcairn Jr. exemplifies this dimension of anti-vaccinationism. As a successful industrialist and philanthropist, Pitcairn brought financial resources, institutional credibility, and social reach to a movement often portrayed as marginal or reactionary.

Pitcairn’s objections to vaccination were closely tied to his broader political philosophy. He viewed compulsory medical intervention as an illegitimate extension of state power into the private sphere, particularly the family. For Pitcairn, vaccination laws represented a dangerous precedent in which governments claimed authority over bodily autonomy under the guise of public welfare. This concern aligned with classical liberal traditions that emphasized individual rights, voluntary association, and skepticism toward centralized authority. His opposition was therefore ideological rather than technical, grounded in principles of governance rather than disputes over medical data.

Elite patronage played a crucial role in shaping the durability and visibility of anti-vaccination movements. Through funding publications, supporting legal challenges, and underwriting organizational activities, figures like Pitcairn helped transform scattered dissent into sustained political pressure. Financial backing enabled anti-vaccination leagues to maintain offices, print literature, and coordinate campaigns over long periods. This support complicates narratives that frame resistance solely as a product of ignorance or social marginality, revealing instead a coalition that crossed class boundaries.

Pitcairn’s involvement also highlights the intersection between wealth, reform, and dissent in the late nineteenth century. His philanthropy extended beyond anti-vaccination activism to broader causes concerned with civil liberty and moral reform. Vaccination resistance became one expression of a larger worldview that questioned the expanding reach of professional expertise and bureaucratic governance. By examining elite patronage, it becomes clear that anti-vaccinationism was not merely a reaction to medicine, but part of a wider debate over authority, citizenship, and the proper limits of state intervention.

Science, Statistics, and the Limits of Evidence

Disputes over vaccination in the nineteenth century frequently turned on questions of evidence rather than outright rejection of scientific reasoning. Both proponents and opponents of vaccination appealed to data, mortality tables, and comparative statistics to support their claims. The conflict lay not in whether evidence mattered, but in how it should be gathered, interpreted, and weighed. In an era before standardized epidemiological methods, statistical reasoning itself was a contested terrain.

Anti-vaccination critics argued that official statistics overstated the effectiveness of vaccination by selectively attributing declines in smallpox mortality to inoculation while ignoring other variables. Improvements in sanitation, nutrition, housing, and quarantine practices coincided with vaccination campaigns, making causal attribution difficult. Critics maintained that correlation was being mistaken for proof, and that public health authorities were too quick to credit vaccination with broader social improvements that had independent origins.

The quality and consistency of data further complicated the debate. Record-keeping varied widely between regions, and diagnostic categories were often imprecise. Smallpox cases could be misclassified, underreported, or conflated with other diseases presenting similar symptoms. Vaccinated individuals who contracted smallpox were sometimes excluded from official tallies or reclassified in ways that minimized perceived failure. Such practices fueled accusations of bias and undermined public trust in medical reporting.

Another limitation concerned the absence of controlled experimentation. Modern standards such as randomized controlled trials did not exist, and ethical norms surrounding experimentation on human subjects were undeveloped. Vaccination outcomes were assessed retrospectively rather than through prospective study, leaving room for disagreement over interpretation. Critics emphasized that population-level statistics could not account for individual risk, especially when adverse reactions, though statistically rare, carried severe consequences.

Proponents of vaccination, for their part, acknowledged imperfections in the data but argued that overwhelming trends demonstrated benefit. They pointed to dramatic reductions in smallpox mortality following widespread vaccination as evidence that outweighed individual anomalies. Yet even among supporters, there was recognition that statistical reasoning was evolving and that conclusions remained provisional. This acknowledgment did little to quell opposition, which seized upon uncertainty as grounds for restraint rather than expansion of policy.

The statistical debates surrounding vaccination reveal a broader epistemological struggle within nineteenth-century science. Medicine was transitioning from individualized clinical judgment to population-based reasoning, a shift that unsettled many observers. Anti-vaccination arguments often reflected discomfort with this transformation, particularly when abstract numerical benefits were invoked to justify concrete personal risks. The limits of evidence were not merely technical shortcomings but indicators of a scientific culture in transition, grappling with how knowledge should guide authority and policy.

Decline, Persistence, and Transformation of Anti-Vaccination Thought

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, several developments began to weaken organized anti-vaccination movements, though they did not eliminate them. Advances in bacteriology and the emergence of germ theory provided a clearer scientific explanation for how vaccines worked, strengthening the intellectual foundations of preventive medicine. Improvements in vaccine production, storage, and administration reduced the incidence of severe adverse reactions that had fueled earlier fears. As vaccination became safer and more effective, its benefits became increasingly visible, particularly in the sharp decline of smallpox epidemics.

Legal and political adjustments also played a role in easing resistance. In response to sustained protest, governments introduced exemptions and conscience clauses that allowed parents to refuse vaccination without facing severe penalties. These compromises did not dismantle vaccination programs, but they reduced the sense of coercion that had galvanized opposition. By acknowledging dissent rather than suppressing it outright, public health authorities mitigated some of the moral outrage that had sustained organized resistance.

At the same time, anti-vaccination thought did not disappear so much as adapt. Earlier arguments grounded in sanitation, natural immunity, and individual liberty were reshaped to fit new scientific and social contexts. As medicine professionalized, critics increasingly positioned themselves as defenders of choice and transparency rather than as challengers of science itself. Skepticism shifted from wholesale rejection of vaccination toward selective questioning of mandates, safety standards, and institutional trustworthiness.

The social composition of resistance also evolved. Whereas nineteenth-century anti-vaccination movements often mobilized mass protest, later forms tended to operate through advocacy, lobbying, and alternative health networks. Print culture gave way to new modes of communication, but the core themes persisted: concern over bodily autonomy, distrust of centralized authority, and unease with expert-driven policy. These continuities reveal that resistance was not tied to a single historical moment but reflected enduring tensions within modern societies.

Understanding this transformation is essential for interpreting the legacy of nineteenth-century anti-vaccinationism. Its decline was not simply a triumph of reason over error, but the result of scientific improvement, political accommodation, and cultural negotiation. The persistence of similar arguments in later periods suggests that vaccination controversies are less about specific technologies than about how societies balance collective welfare, individual rights, and trust in expertise. Anti-vaccination thought changed form, but the questions it raised about authority and consent did not vanish.

Conclusion: Dissent, Science, and Historical Humility

The history of nineteenth-century anti-vaccinationism resists simple moral classification. It cannot be reduced to ignorance, superstition, or hostility toward science without distorting the conditions under which it emerged. Opposition to vaccination arose in a period marked by genuine medical uncertainty, uneven standards of evidence, and expanding state authority over private life. Many critics engaged seriously with data, ethics, and political theory, even as their conclusions diverged from those that would later prevail.

This history also underscores the provisional nature of scientific authority. Vaccination ultimately proved to be one of the most successful public health interventions in human history, but its early development was neither seamless nor uncontested. Adverse outcomes, inconsistent practices, and limited explanatory frameworks left room for doubt. Dissent functioned, at times, as a pressure that forced public health institutions to refine methods, improve safety, and articulate clearer justifications for intervention. In this sense, resistance was not external to scientific progress but entangled with it.

Equally important is the role of power in shaping medical acceptance. Compulsory vaccination transformed a technical debate into a political struggle, linking questions of health to broader concerns about consent, liberty, and governance. The persistence of anti-vaccination arguments reflects enduring tensions within modern societies over who decides what risks are acceptable and on what grounds. These tensions did not vanish with the arrival of germ theory or improved vaccines; they were merely reframed.

Historical humility requires recognizing that past actors operated within constraints different from our own. The figures examined in this essay were not responding to settled science but to an evolving body of knowledge mediated by social experience and institutional trust. Understanding their objections does not require endorsing them. It requires acknowledging that dissent is a recurring feature of scientific change, particularly when knowledge intersects with authority and the human body. The lesson of nineteenth-century anti-vaccinationism is not that expertise should be rejected, but that it must be exercised with transparency, restraint, and respect for the conditions under which trust is earned.

Bibliography

- Colgrove, James. State of Immunity: The Politics of Vaccination in Twentieth-Century America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

- Durbach, Nadja. Bodily Matters: The Anti-Vaccination Movement in England, 1853–1907. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.

- Fichman, Martin. An Elusive Victorian: The Evolution of Alfred Russel Wallace. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Gibbs, John. Our Medical Liberties. London: National Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League, 1882.

- Hacking, Ian. The Taming of Chance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Kalter, Lindsay. “Blood Hands, Dirty Knives: The Horrors of Victorian Medicine.” American Association of Medical Colleges (Oct. 20, 2018).

- Millward, Gareth. Vaccinating Britain: Mass Vaccination and the Public since the Second World War. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019.

- Moseley, Benjamin. A Treatise on the Lues Bovilla, or Cow-Pox. London: J. Johnson, 1805.

- Porter, Roy. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity. New York: W. W. Norton, 1997.

- Porter, Roy. Disease, Medicine and Society in England, 1550–1860. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Rosenberg, Charles E. The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

- Rowley, William. Cow-Pox Inoculation No Security Against Small-Pox Infection. London: J. Callow, 1805.

- Tebb, William. A Century of Vaccination and What It Teaches. London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1899.

- Wallace, Alfred Russel. Vaccination a Delusion: Its Penal Enforcement a Crime. London: E. W. Allen, 1898.

- Weber, Thomas P. “Alfred Russel Wallace and the Antivaccination Movement in Victorian England.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 16:4 (2010): 664-668.

- Williams, Gareth. Angel of Death: The Story of Smallpox. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Wolfe, Robert M., and Lisa K. Sharp. “Anti-Vaccinationists Past and Present.” BMJ 325, no. 7361 (2002): 430–432.

- Worboys, Michael. Spreading Germs: Disease Theories and Medical Practice in Britain, 1865–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.12.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.