Augustus’ rule stands as one of history’s greatest paradoxes: a revolution executed in the language of restoration. He dismantled the Republic without abolishing it, turning its institutions into ornaments of obedience.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Death of the Republic in the Guise of Restoration

When Gaius Octavius, later known as Augustus, rose to power in the chaotic aftermath of Julius Caesar’s assassination, few Romans grasped that they were witnessing the quiet death of their Republic. Where Caesar had been open in his ambition, Octavian mastered concealment. His ascent was not a seizure of power but a performance of humility. In public he vowed to restore the old order; in practice, he hollowed it out from within. By the time the Senate granted him the name Augustus in 27 BCE, the Republic remained in form but not in substance.1

Rome’s citizens, exhausted by decades of civil conflict, longed for stability more than liberty. Augustus recognized this yearning and used it to reshape the political landscape. As Mary Beard has observed, his genius lay in maintaining “the permanent make-believe that the Republic had been restored,” a façade that made his rule palatable to a weary populace.2 Unlike his adoptive father, Augustus never crowned himself; instead, he invited the Senate to do it for him.

This illusion of continuity, of freedom preserved under the mask of monarchy, became the cornerstone of his new political order. Later historians called this transformation a “revolution disguised as a restoration,” a reordering of the Roman world that cloaked autocracy in republican dress.3 Augustus’ careful restraint, deferential gestures, and invocation of ancestral virtue convinced Rome that it had been saved, not subdued.

The Republic did not fall in battle; it was embalmed in ceremony. Augustus preserved its outer forms so well that Romans could continue believing in them. His reign thus represents the most extraordinary political sleight of hand in history: a monarchy born under the pretense of moral renewal, a revolution achieved through consent rather than conquest.

From Heir to Savior: Octavian’s Rise After Caesar’s Death

Octavian’s political apprenticeship unfolded amid shifting loyalties. His alliance with Marcus Antonius and Marcus Lepidus in the Second Triumvirate of 43 BCE was an act of cold calculation rather than trust. Together, they avenged Caesar’s murder, purging opponents through the infamous proscriptions that filled Rome’s streets with blood. Yet even at this stage, Octavian understood that terror alone could not sustain power. He used the violence of the Triumvirate as a temporary necessity, a grim means to a moral end, before positioning himself as the healer who would restore the Republic once the “traitors” were punished.4

After defeating Brutus and Cassius at Philippi in 42 BCE, the young ruler turned his gaze inward, toward Antony himself. Antony’s descent into scandal and his alliance with Cleopatra offered Octavian a perfect contrast. Through carefully orchestrated propaganda, Octavian cast himself as the embodiment of Roman virtue against Antony’s eastern decadence.5 The decisive victory at Actium in 31 BCE was thus not merely a military triumph but a moral one. Octavian returned to Rome not as a conqueror, but as a savior who had preserved Roman identity from corruption and chaos.

Octavian’s genius lay in this performance of restraint. While Julius Caesar had reached too visibly for the crown, Octavian appeared to decline it. His actions (disbanding legions, deferring to the Senate, and adopting the rhetoric of republican restoration) convinced a weary populace that he sought peace, not power.6 Behind the façade, however, he consolidated every crucial instrument of control: the loyalty of the army, the allegiance of provincial governors, and the financial machinery of the state. By the time he formally accepted the title Augustus in 27 BCE, there was no Republic left to restore. The Senate’s acclamations were not resistance but ritual submission, the final act of a long play he had written himself.7

Octavian had succeeded where Caesar failed because he understood the psychology of legitimacy. To seize power was dangerous; to be begged to take it was divine. His transformation into Augustus would complete the illusion, the monarch who ruled by consent, the emperor who pretended not to be one.

The Veiled Monarchy: The First Settlement of 27 BCE

In 27 BCE, Octavian performed one of the most extraordinary political maneuvers in Roman history. Standing before the Senate, he announced that he was relinquishing his extraordinary powers and returning authority to the Republic. The gesture appeared selfless, almost saintly, the victorious leader renouncing control for the sake of liberty. But it was a masterwork of deception. The Senate, overwhelmed with gratitude, insisted that he retain command over several key provinces, notably those housing the majority of Rome’s legions.7 In one motion, the Republic was “restored,” and Octavian secured an unchallengeable military base from which to rule indefinitely.

This carefully staged performance, later known as the “First Settlement,” marked the true birth of the Principate, the system by which Augustus ruled as princeps, “first citizen,” rather than king. The semantics mattered deeply. Rome’s hatred of monarchy had endured for nearly five centuries, ever since the expulsion of Tarquin the Proud. By claiming only primacy within the Republic, not dominion over it, Augustus could embody continuity rather than rupture.7 He wielded imperium maius, supreme military authority, while presenting himself as the guardian of senatorial tradition.

Augustus’ political language drew heavily on the concept of auctoritas, a term that connoted moral weight rather than formal office. As Karl Galinsky explains, this moral authority gave legitimacy to power that was otherwise extra-constitutional: Augustus “disguised domination as service, empire as restoration.”7 In effect, he replaced the visible crown with invisible consent. The Senate still met, magistrates still held office, elections still occurred, but their outcomes no longer mattered.

Symbols of continuity thus masked the structure of autocracy. Coins bore the image of Augustus beside traditional emblems of the Republic. Public monuments like the Forum of Augustus evoked ancestral virtue while glorifying his personal achievements. The illusion was total: Rome appeared unchanged, yet every lever of power now answered to one man.8 What had been a collective republic of laws became a monarchy of perception, where freedom persisted only in ceremony.

The First Settlement succeeded because it offered Romans precisely what they thought they wanted: peace without acknowledging the price. The Republic, exhausted by its own dysfunction, accepted servitude under the guise of stability. Augustus’ brilliance was to make the surrender voluntary, a revolution that felt like redemption.

Rewriting the State: The Second Settlement and the Illusion of Shared Power

In 23 BCE Augustus made another calculated gesture that deepened his control while appearing to limit it. He resigned the consulship, an office he had held almost continuously since 31 BCE, and in doing so seemed to release his grip on the Republic’s highest magistracy. In truth, the “Second Settlement” merely redistributed his supremacy into new forms. The Senate granted him imperium maius proconsulare, authority that surpassed that of every other governor, valid across all provinces. He also received the powers of a tribune for life, the tribunicia potestas, giving him the right to convene the Senate, propose legislation, and veto any act of any magistrate.9

This constitutional sleight of hand ensured that Augustus could rule without office, dominate without title, and command without appearing to do either. The new arrangement allowed him to avoid the resentment that the consulship provoked while still directing both civil and military affairs. The Senate and people continued to function, but only as instruments of affirmation. As Werner Eck observes, the settlement “transformed the Republic into a monarchy camouflaged in republican terminology.”10

The illusion of collaboration extended beyond legal forms. Augustus meticulously cultivated deference to the Senate, referring to himself as its “servant.” In the Res Gestae, he claimed to have excelled all others in auctoritas but to have possessed “no greater power than those who were my colleagues in office.”11 The statement was technically true, his powers were extraordinary precisely because they existed outside the normal system. Through this rhetoric, Augustus recast absolute rule as collegial stewardship.

Even the provinces reflected this careful fiction. Those under senatorial administration were nominally free from his direct control, but his legates governed the imperial provinces where the armies were stationed. The appearance of balance masked a monopoly: Augustus held the sword, while the Senate held the pen.12 Rome’s citizens, meanwhile, were soothed by peace and prosperity, unaware, or unwilling to admit, that liberty had become ceremonial.

By dividing power in form but not in fact, Augustus perfected the architecture of durable autocracy. He had learned from the Republic’s death throes that legitimacy depended on participation, or at least the performance of it. In the Second Settlement, he built a system that could endure precisely because it convinced the ruled that they were still governing themselves.

The Politics of Virtue and Image: Propaganda, Religion, and Morality

Having secured control of the Roman state, Augustus turned to shaping the moral and cultural foundations that would sustain it. His authority, though unprecedented, rested on a delicate balance between appearance and belief. To maintain the illusion of republican virtue, he presented himself not as a ruler of men but as the restorer of mos maiorum—the ancestral customs that defined Roman identity. This ideological project transformed politics into morality, and morality into propaganda.

Central to this effort was the revival of traditional religion. Augustus rebuilt or restored more than eighty temples in Rome, reviving ceremonies that had fallen into neglect during the civil wars.13 He assumed the role of pontifex maximus in 12 BCE, binding piety to governance and placing divine sanction upon his rule. The rituals of the Republic became instruments of imperial ideology. As Karl Galinsky notes, Augustus’ religious policy “blurred the distinction between civic virtue and loyalty to the ruler,” making devotion to the gods inseparable from allegiance to the princeps.14

Art and literature magnified this transformation. The Ara Pacis Augustae, completed in 9 BCE, celebrated the Pax Romana, a peace that depended entirely on his authority. Its reliefs depicted harmony among gods and mortals, families and ancestors, all converging toward the person of Augustus. The message was unmistakable: order flowed from him. In the literary realm, poets like Virgil, Horace, and Propertius echoed the same theme. In the Aeneid, Aeneas’ obedience to divine will becomes a prototype for Augustus’ own mission, turning imperial destiny into sacred narrative.15 Horace, meanwhile, framed loyalty to Augustus as the highest civic virtue, his odes blending private morality with public devotion.16

Moral reform became another tool of consolidation. Through legislation such as the Lex Julia de Maritandis Ordinibus and the Lex Papia Poppaea, Augustus sought to regulate marriage, inheritance, and sexual conduct, presenting himself as the guardian of virtue in an age of decay.17 These laws, though often ignored in practice, reinforced the symbolic role of Augustus as pater patriae, the father of the nation, whose moral authority justified political supremacy. By policing the private sphere, he claimed dominion over the Roman conscience.

Propaganda, religion, and legislation thus converged into a unified system of persuasion. The Republic had relied on competition for glory; Augustus replaced it with competition for virtue defined by his example. The Senate still debated, poets still sang, priests still sacrificed, but all within an order that radiated outward from one man. As Paul Zanker argues, “the visual language of power became a moral language,” binding aesthetics, ethics, and authority into the new imperial ideology.18

In this way, Augustus achieved a revolution not merely of government but of values. The Republic’s political freedoms had been replaced by the promise of moral renewal. Romans, fatigued by violence and disorder, accepted the exchange. Peace, prosperity, and piety became the new trinity of imperial faith, and Augustus its high priest.

The Legacy of Disguised Despotism

By the time Augustus died in 14 CE, Rome had forgotten what a true Republic looked like. The machinery of republican governance still turned, consuls were elected, the Senate convened, magistrates wore their insignia, but the spirit that had animated it was gone. What remained was a pageant of participation. The illusion had outlived the illusionist.19

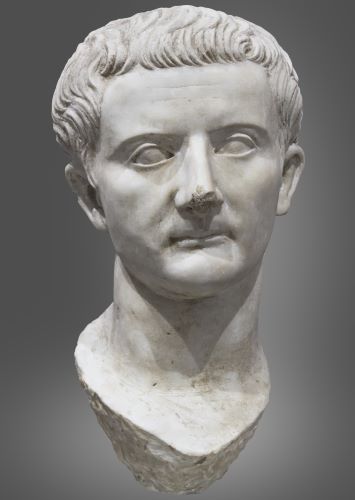

Augustus’ system endured precisely because it satisfied both sides of the Roman temperament: the craving for order and the nostalgia for freedom. He offered peace in exchange for submission but wrapped it in the comforting rhetoric of tradition. His successors inherited not only his powers but his masks. Tiberius governed as princeps; Claudius and Nero retained the Senate as a stage prop; even under the worst emperors, the fiction of collective rule persisted.20 The institutions survived because they had been emptied of risk. In Rome’s political imagination, liberty had been domesticated, reduced from a public virtue to a sentimental memory.

This transformation was not merely political but psychological. As Ronald Syme observed, Augustus had “destroyed the oligarchy of the nobiles only to replace it with the monarchy of himself.”21 Yet the people did not feel conquered. They had been seduced by security, spectacle, and prosperity, the dividends of submission. The Pax Romana became both the justification for the new order and the narcotic that sustained it. To rebel against it was to seem ungrateful for peace.

The endurance of this illusion speaks to a deeper truth about power: that the most stable despotisms are not imposed by force but accepted by habit. Augustus’ brilliance lay in understanding that revolutions fail when they proclaim themselves. His succeeded because it disguised itself as restoration. Through careful ritual, language, and imagery, he convinced Rome that continuity was change, and that obedience was virtue.

In the centuries that followed, emperors from Hadrian to Constantine would claim descent not only from Augustus’ bloodline but from his political theology, the art of ruling by consent to illusion. His legacy persists wherever authority clothes itself in the language of preservation, and where citizens mistake stability for freedom. The Republic did not die of tyranny; it died of comfort.

Conclusion: The Emperor Who Pretended Not to Be One

Augustus’ rule stands as one of history’s greatest paradoxes: a revolution executed in the language of restoration. He dismantled the Republic without abolishing it, turning its institutions into ornaments of obedience. The Senate still conferred honors, magistrates still held elections, and citizens still imagined themselves free, but every gesture of participation confirmed the permanence of his power.22 In a single lifetime, the old Roman balance between liberty and order was inverted. Where the Republic had once feared monarchy as tyranny, Augustus taught Rome to worship it as peace.

His mastery of appearances made him not merely a political founder but an architect of illusion. Through the careful blending of humility and command, tradition and innovation, he ensured that domination appeared as duty.23 The Res Gestae, his own curated epitaph, records not conquest but service, not power but piety. It is a document of concealment, a political mirror in which Romans saw only what they wished to see: salvation through submission.

The durability of Augustus’ settlement, surviving for centuries after his death, reveals how effectively he redefined the very idea of legitimacy. By making power seem moral, he erased the line between ruler and benefactor, authority and virtue. His successors inherited not a throne but a vocabulary, a way to speak tyranny in the syntax of freedom.24

In the end, Augustus’ empire was not built on force but on faith: faith in stability,25 faith in the old names, faith that nothing fundamental had changed.26 Yet everything had. The Republic’s ideals lingered as memory, its offices as ritual, its people as spectators to their own surrender. History rarely records a more elegant end to freedom. Rome’s first emperor became immortal not because he conquered the world, but because he convinced it that he had saved it.27

Appendix

Endnotes

- Res Gestae Divi Augusti 34; Suetonius, Divus Augustus 7.

- Mary Beard, SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome (New York: Liveright, 2015), 385.

- Ronald Syme, The Roman Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939), vii.

- Appian, Civil Wars 4.

- Plutarch, Life of Antony 54–56; Cassius Dio 50.

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Augustus: First Emperor of Rome (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 116–120.

- Suetonius, Divus Augustus 7–10.

- Cassius Dio 53.12–17.

- Res Gestae Divi Augusti 34; see also Werner Eck, The Age of Augustus, trans. Deborah Lucas Schneider (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003), 30–35.

- Karl Galinsky, Augustus: Introduction to the Life of an Emperor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 53.

- Paul Zanker, The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990), 89–94.

- Cassius Dio 53.32–33.

- Werner Eck, The Age of Augustus, trans. Deborah Lucas Schneider (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003), 38–41.

- Res Gestae Divi Augusti 34.

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Augustus: First Emperor of Rome (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 171–175.

- Res Gestae Divi Augusti 19–21.

- Karl Galinsky, Augustus: Introduction to the Life of an Emperor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 120–124.

- Virgil, Aeneid 6.847–853; see also Denis Feeney, Literature and Religion at Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 211–214.

- Horace, Odes 3.5; see also Llewelyn Morgan, Patterns of Redemption in Virgil’s Georgics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 182.

- Suetonius, Divus Augustus 34.

- Paul Zanker, The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1988), 123.

- Tacitus, Annals 1.1–3.

- Fergus Millar, The Emperor in the Roman World (31 BC–AD 337) (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977), 68–72.

- Ronald Syme, The Roman Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939), 512.

- Res Gestae Divi Augusti 34; Cassius Dio 53.12–17.

- Karl Galinsky, Augustus: Introduction to the Life of an Emperor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 183.

- Mary Beard, SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome (New York: Liveright, 2015), 390.

Bibliography

- Appian. The Civil Wars. Translated by Horace White. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1913.

- Beard, Mary. SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. New York: Liveright, 2015.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History. Translated by Earnest Cary. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914–1927.

- Eck, Werner. The Age of Augustus. Translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider. Oxford: Blackwell, 1891.

- Feeney, Denis. Literature and Religion at Rome: Cultures, Contexts, and Beliefs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Galinsky, Karl. Augustus: Introduction to the Life of an Emperor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian. Augustus: First Emperor of Rome. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

- Horace. Odes. Translated by C. E. Bennett. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914.

- Millar, Fergus. The Emperor in the Roman World (31 BC–AD 337). Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977.

- Morgan, Llewelyn. Patterns of Redemption in Virgil’s Georgics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Plutarch. Lives, Volume IX: Demetrius and Antony, Pyrrhus and Gaius Marius. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1920.

- Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars: Divus Augustus. Translated by Robert Graves. Revised by J. B. Rives. London: Penguin Classics, 2007.

- Syme, Ronald. The Roman Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939.

- Tacitus. The Annals. Translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1876.

- Virgil. Aeneid. Translated by H. Rushton Fairclough. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1916.

- Zanker, Paul. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1988.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.20.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.