The war chariot dominated the battlefield, altering the strategies of kings and the fates of empires. Yet its utility proved fragile, undermined by terrain, cost, and the rise of cavalry.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The war chariot stands among the most striking inventions of the ancient world, a machine that combined technological ingenuity with political ambition. It was at once a tool of conquest, a platform for kings, and a stage for the gods. Yet the chariot’s career was brief compared to its symbolic legacy. From its emergence in the Bronze Age to its eclipse by cavalry in the first millennium BCE, the chariot transformed the scale and spectacle of war. Historians have long debated whether its true significance lay in battlefield utility or in the display of prestige and divine sanction.1 Whatever the balance, its presence altered the dynamics of early empires and left an imprint on the imagination of later cultures.

Origins and Early Development

The origins of the chariot are tied to two parallel technological revolutions: the domestication of the horse and the refinement of the wheel. Solid wheels, known from Mesopotamia as early as the fourth millennium BCE, allowed the construction of heavy carts drawn by oxen.2 These vehicles were slow and ill-suited to war. The breakthrough came with the invention of the light spoked wheel, which reduced weight and made rapid movement possible. Archaeological finds at Sintashta and related steppe cultures dating to around 2000 BCE reveal horse burials accompanied by two-wheeled vehicles with clear chariot characteristics.3

What began as an adaptation of pastoral transport became a military revolution. For the first time, human speed and strength were augmented by a harnessed animal team capable of rapid, sustained charges. The chariot thus emerged not in the heartlands of the first civilizations but on the margins, among semi-nomadic peoples who blended horsemanship with metallurgical skill. From there it radiated outward, adopted and transformed by empires that recognized its power.

Chariots in the Ancient Near East

Mesopotamia and Sumer

Depictions from the Royal Standard of Ur (c. 2600 BCE) suggest that early Mesopotamian elites employed heavy four-wheeled battle carts. Drawn by equids, probably onagers rather than true horses, they carried armed men into combat. These early carts were cumbersome, functioning more as mobile platforms for elite warriors than as instruments of shock attack.4 Their primary value lay in prestige and intimidation, signaling the wealth necessary to maintain such teams.

Egypt and the New Kingdom

The Hyksos invasion of Egypt in the seventeenth century BCE introduced the horse-drawn chariot to the Nile Valley, where it was rapidly integrated into the military system. By the time of Thutmose III, Egyptian armies fielded thousands of light, fast chariots manned by archers capable of delivering volleys while circling enemy formations.5 The Battle of Megiddo (c. 1457 BCE) demonstrated the decisive role chariotry could play in projecting power across the Levant.

The apogee of Egyptian chariotry came under Ramses II at Kadesh (c. 1274 BCE), where Hittite and Egyptian forces clashed in one of the largest recorded chariot battles of antiquity. Egyptian reliefs depict disciplined squadrons maneuvering with precision, though modern historians caution that these accounts likely exaggerate Egyptian control.6 Still, the encounter shows that by the Late Bronze Age, the chariot had become the centerpiece of interstate warfare.

Hittites and Anatolia

The Hittites developed heavier chariots with three-man crews: a driver, a shield-bearer, and a spearman. This design emphasized shock rather than speed, trading maneuverability for impact. At Kadesh, Hittite chariots nearly overwhelmed the Egyptian line before being checked by reinforcements.7 Beyond the battlefield, chariots were deeply embedded in Hittite royal ideology, featuring in royal iconography and diplomatic gift exchanges. In this way, the chariot became both weapon and currency of power.

Chariots in the Indo-Iranian World

The Aryan Expansion

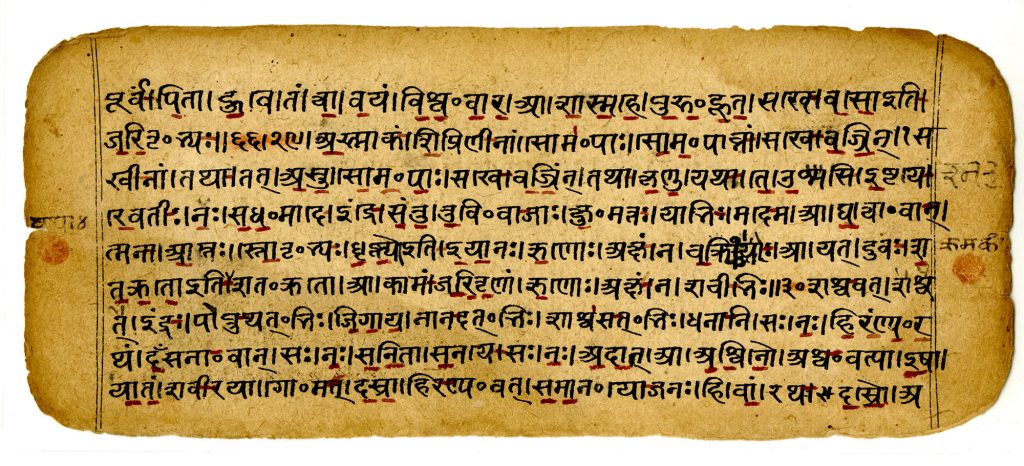

As Indo-Iranian groups expanded into South Asia, the chariot carried with it a potent symbolic charge. The Rigveda, composed around the second millennium BCE, celebrates warrior-chiefs who thunder into battle upon resplendent chariots, aided by gods who themselves drive celestial cars.8 The chariot here was not merely a tactical tool but an axis between the human and the divine.

Persia and the Achaemenids

By the time of the Achaemenid Empire, chariot warfare had become less decisive. Persian kings maintained scythed chariots, outfitted with blades projecting from the wheels, designed to tear through infantry formations. Accounts of the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE) describe Alexander’s troops calmly parting ranks to let these machines pass before closing ranks again.9 Once formidable, the chariot had by then become a liability in the face of disciplined infantry and increasingly effective cavalry.

Yet their very inclusion on the battlefield reveals how deeply embedded chariots remained in Persian royal ideology. The spectacle of serried ranks of scythed chariots charging across the plain evoked both ancestral memory and divine sanction. To abandon them outright would have seemed to sever continuity with a tradition that linked Persian kingship to ancient Aryan and Mesopotamian precedent. Their persistence, even in obsolescence, underscores the complex interplay of ritual, memory, and pragmatism in ancient warfare.10

Chariots in the Mediterranean and Europe

Mycenaean Greece

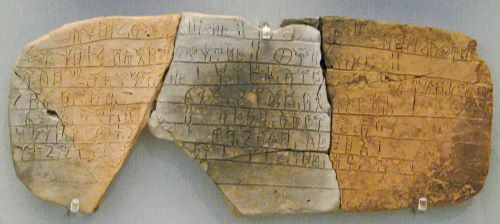

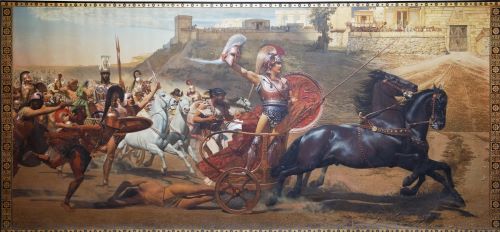

Linear B tablets record references to chariot equipment, and Homer’s Iliad abounds with vivid images of heroes leaping from their chariots to fight on foot. Scholars debate whether this represents an echo of real practice or a poetic archaism. Archaeological remains suggest that Mycenaean elites valued the chariot as a status symbol, used both in warfare and ceremonial contexts.11 The dual nature of the chariot, as real weapon and imagined stage, was especially pronounced in Greece.

Celtic and British Isles

Chariots persisted in the Iron Age cultures of Europe, particularly among the Celts. Julius Caesar’s Gallic Wars describes British warriors driving their chariots with daring skill, leaping off to fight before remounting to retreat or pursue.12 These tactics astonished Roman observers, though their effectiveness was limited against disciplined legions. Still, the persistence of chariotry in the peripheries of Europe illustrates its adaptability across cultural contexts long after its decline in the great empires.

Decline and Transformation

The Rise of Cavalry

The fundamental weakness of the chariot was its dependence on suitable terrain. In rough or uneven ground, it became useless. Mounted cavalry, which required no vehicle and could operate independently, eventually supplanted it. By the first millennium BCE, horse archers from the steppe and heavy cavalry in the Near East made the chariot redundant.13 The transition was gradual, but by the classical period, chariot warfare was obsolete.

This shift marked more than a tactical change; it reshaped the very structure of ancient armies. Cavalry units required different systems of training, logistics, and command, favoring societies with strong equestrian traditions. The rise of cavalry also altered class structures, since individual horsemen often bore the cost of their mounts, saddlery, and weapons. What had once been a spectacle concentrated in the hands of kings and courts now became distributed among aristocratic elites, laying the groundwork for new forms of military aristocracy in both East and West.14

Persistence in Ceremony and Sport

Even as battlefield utility waned, the chariot retained enormous cultural prestige. In Greece and Rome, it became central to athletic contests, with races in Olympia and at the Circus Maximus attracting vast crowds. Triumphal processions carried generals in gilded chariots, a reminder of their ancient military associations. Thus the chariot lived on as a spectacle of glory long after its martial role had ended.

Cultural and Symbolic Dimensions

Chariots in Myth and Epic

The chariot’s symbolic power extended deeply into myth. Helios drove the sun across the sky in a blazing car; Surya, the Vedic solar deity, performed a similar function. Heroes such as Achilles, Krishna, and Arjuna are all imagined as charioteers, embodying the link between martial valor and divine destiny.15 These images ensured that even when chariots disappeared from armies, they remained embedded in the cultural psyche.

Archaeological Legacy

Chariot burials from China to the Eurasian steppe, as well as elaborate tomb reliefs, testify to their role in defining elite status. The presence of chariots in royal graves suggests they were considered essential to identity and authority, ensuring mobility even in the afterlife¹⁶. Archaeology thus confirms what texts imply: the chariot was as much an emblem of rule as a practical tool of war.

Conclusion

The history of the war chariot illustrates the paradox of ancient military technology. For a few centuries it dominated the battlefield, altering the strategies of kings and the fates of empires. Yet its utility proved fragile, undermined by terrain, cost, and the rise of cavalry. Despite this, the chariot’s symbolic resonance endured for millennia, preserved in ritual, myth, and spectacle. The machine that once thundered across Kadesh and Gaugamela lingered on in memory, a reminder that in human history, the line between power and performance is never wholly clear.

Appendix

Notes

- Trevor Bryce, The World of the Neo-Hittite Kingdoms (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 57.

- Andrew Sherratt, “The Secondary Exploitation of Animals in the Old World,” World Archaeology 15, no. 1 (1983): 90–104.

- David Anthony, The Horse, the Wheel, and Language (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), 392–405.

- Dominique Collon, First Impressions: Cylinder Seals in the Ancient Near East (London: British Museum Press, 1987), 44.

- Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 210–15.

- Kenneth Kitchen, Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II (Warminster: Aris & Phillips, 1982), 47–59.

- Bryce, World of the Neo-Hittite Kingdoms, 112–14.

- Stephanie Jamison and Joel Brereton, The Rigveda: A Translation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 215.

- Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, 3.13.5.

- Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1996), 563–65.

- Oliver Dickinson, The Aegean Bronze Age (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 162–65.

- Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico, 4.33.

- John Keegan, A History of Warfare (New York: Vintage, 1993), 178–80.

- Philip Sabin, The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare, Vol. I (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 137–40.

- Wendy Doniger, The Hindus: An Alternative History (New York: Penguin, 2009), 143–44.

Victor Mair, The Tarim Mummies (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000), 135–42.

Bibliography

- Anthony, David. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Arrian. Anabasis of Alexander. Translated by P.A. Brunt. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- Briant, Pierre. From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1996.

- Bryce, Trevor. The World of the Neo-Hittite Kingdoms: A Political and Military History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Caesar, Julius. The Gallic War. Translated by H.J. Edwards. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1917.

- Collon, Dominique. First Impressions: Cylinder Seals in the Ancient Near East. London: British Museum Press, 1987.

- Dickinson, Oliver. The Aegean Bronze Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Doniger, Wendy. The Hindus: An Alternative History. New York: Penguin, 2009.

- Jamison, Stephanie, and Joel Brereton. The Rigveda: A Translation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Keegan, John. A History of Warfare. New York: Vintage, 1993.

- Kitchen, Kenneth. Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II. Warminster: Aris & Phillips, 1982.

- Mair, Victor. The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

- Sabin, Philip. The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare, Vol. I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Shaw, Ian. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Sherratt, Andrew. “The Secondary Exploitation of Animals in the Old World.” World Archaeology 15, no. 1 (1983): 90–104.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.18.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.