The King’s Library / Wikimedia Commons

By Dr. Peter Jones

Professor of History

University of Birmingham, UK

Abstract

The term “enlightenment”, as a noun or adjective, has been widely used by 20th-century historians to cover a multitude of ideas and activities in the 18th century, many of which were quite unknown to their contemporaries. The categories and taxonomies used by historians, and their normative allegiances, are not immune from revision, however, and use of the term may diminish as detailed contextual enquiries examine more carefully than hitherto the thought and action of the period. During the last two hundred years the meaning and implications of many familiar terms have changed greatly. There is no single tenet, practice or meaning to which everyone adhered, in different cultures, during the ‘enlightenment period’. Although many writers advocated sceptical enquiry into the nature of knowledge, nature, society and the human condition, few held that answers were to be found by the exercise of “reason alone”; and most were influenced, at least indirectly, by technological and scientific resources and understanding of the day.

Terminology

Although its German equivalent “Aufklärung” was apparently introduced to the German language in the 1780s, even a century later, in English the term “Enlightenment” was understood to refer to the French movement only.1 Yet it has been used widely by 20th-century historians to cover a multitude of ideas and activities in the 18th century, many of which were not known to all of their contemporaries.2 The term is generally understood to refer to the period of approximately 1750–1790 and includes many writers, thinkers and practitioners in various fields, principally in France and Germany – although, since the 1960s, efforts have been made to embrace varied activities in different regions of Europe.3 However, the differences have typically weakened the value of the classification.

Adam Smith (1723–1790) was professor of logic and philosophy in Glasgow. He became famous primarily for his economic theories, which he published in 1776 in his magnum opus The Wealth of Nations. He is considered the founder of national economy, which also provided the theoretical basis for free trade. / Adam Smith (1723–1790), copperplate engraving, 1805, unknown artist; image source: Library of Congress

The English philosopher John Locke is considered to be the founder of empiricism and the Enlightenment critique of knowledge. In particular, his epistemological magnum opus An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) and his writings on the state (Two Treatises of Government, 1690; Letter Concerning Toleration, 1689) had a significant impact upon, amongst others, Hume, Voltaire and Kant, as well as the liberal concept of the constitutional state. / Portrait of John Locke (1632–1704), lithography by de Fonroug[e] after H. Garnier, undated; source: Library of Congress

The lawyer and historian Samuel Pufendorf (from 1694 Freiherr von Pufendorf) developed the leading system of state theory and rational law in enlightened absolutism (De jure naturae et gentium libri octo, 1672) on the basis of a rationalistic interpretation of natural law. He combined concepts of freedom and the dignity of man with the inherent requirements of the state, with reasons of state and with sovereignty in a theory of duties that made a clear distinction between law and morality, and employing a concept of international law based on natural law. / Samuel von Pufendorf (1632–1694), etching, approx. 20,6 × 32,1 cm, 1729, unknown artist; source: Pufendorf, Samuel Freiherr von: De rebus a Carolo Gustavo Sveciae rege gestis commentariorum: Sumptibus Christophori Riegelii, Literis Bielingianis, Norimbergae MDCCXXIX [1729], Wikimedia Commons

For example, Scotland, with its weak rural economy until the 1750s, its Calvinism and Roman Dutch law, was hardly comparable to commercial England, with its Anglicanism and Common law. Moreover, Scottish professors of philosophy, such as Adam Smith (1723–1790) , were pedagogues charged with the moral education of the young, closely watched by religious leaders. They were influenced less by John Locke (1632–1704) than by continental philosophers such as Pierre Bayle (1647–1706) and Nicholas Malebranche (1638–1715) , and jurists such as Samuel Pufendorf (1632–1694) and Jean Barbeyrac (1674–1744) : It was not their role to promote radical thought in the classroom. Secular scepticism repelled the clergy of all persuasions throughout Britain, and most practising scientists steered clear of religious controversy. In any case, in England there were no philosophers of the stature of the Scottish thinkers David Hume (1711–1776) and Adam Smith, or their French contemporaries, and there was far less discussion than elsewhere on the relative influence of reason or passion over human actions – or, indeed, on how those notions were to be understood.

Just as there are overlapping threads in a long rope, but no single strand, there is no single tenet or practice to which everyone adhered during the “Enlightenment” period, although many writers advocated individual freedom of thought, speech, and action – variously understood and qualified. Advocacy of “equality and justice under the law”, although not widespread, increased towards the end of the 18th century, and support for limitless enquiry was qualified. Knowledge claims by some authorities were treated with scepticism – the Irish writer and statesman Edmund Burke (1729–1797) , considered to be the founder of modern conservatism, actually objected to the notion that “everything is to be discussed”.4

It has been pointed out that very few English, French, German, Italian, Scottish, or Swiss philosophers in the 18th century were democrats, materialists or even atheists; and, almost everywhere, those who espoused enlightened ideas proceeded within the rules of the social game.5 A priority among leading citizens throughout the more “enlightened” parts of Europe was the appropriate and effective application of scientific ideas and practice to agriculture, mining, communication and health. But even the perennial concern with “how to live” was interpreted in diverse ways, and no one definition embraces the ways in which self-consciously chosen terms were used – such as “science”, “scepticism”, “atheist”, “Newtonian”, “principle”, “evidence”, and “theory”.6 And although terms such as “freedom” or “liberty” were increasingly and polemically re-defined towards the end of the 18th century, other recurrent terms such as “market”, “economy”, and “state” inherited meanings from antiquity and religious philosophy quite alien to modern readers.7

Throughout the 18th century, writers, politicians and preachers reflected widely on appropriate means of communication, as did popularisers of contemporary scientific and social views, and the inherited traditions of rhetoric alerted them to the importance of identifying contexts: What could they tell or not tell, and sell effectively, to whom, when, why, and where?8 Such questions, although they were often only implicitly asked, prompted other considerations about interpretation, conceptual change, the relation of language to the world and, more deeply, of thought to action. In spite of such potentially unsettling reflection, almost all who sought or held political, religious, military or social power intended to hold on to it. This explains why, throughout much of Europe, political “freedom” and enquiry were regarded as subversive, whereas economic “freedom” was increasingly seen as an attractive means to commercial success.

Like on other contentious labels, such as “democratic”, “liberal”, and “scientific”, modern debate has concentrated as much on the legitimacy of their application as on the issues which, sometimes quite casually, they categorised. In 1932, the German philosopher Ernst Cassirer (1874–1945) sought to counter the still influential hostile verdict of the Romantic Movement on the Enlightenment. He insisted that whilst many individuals in the 18th century “rework[ed] prevailing ideas” and “continued to build” on 17th century foundations, they nevertheless provided a new perspective and gave new meaning to those ideas. According to Cassirer, the “constantly fluctuating activity of [enquiry and reflection at the time] cannot be resolved into a mere summation of individual teachings” and the character of the period could be grasped only in “the form and manner of intellectual activity in general”.9

In spite of Cassirer’s scholarship, subsequent historians have typically joined one of two camps – the camp of the “realists” who believe that historical periods have independent identities, with “essential” features (the candidates for which are hotly contested);10 and “conventionalists”, who regard labels as convenient devices for marshalling material which are always open to revision or rejection as their use diminishes. Realists tend to ignore changing social, political, and religious contexts or practices, in spite of the fact that recently conventionalists have underlined the diversity of cultural forms across geographical and political boundaries, thus deriving insights from tenets in the sociology of knowledge.11

Modern historians rarely refer to the debates about “periodization” and its theoretical constraints, which occupied historians of the Renaissance from the 1930s onwards.12 Instead, they have concentrated more on whether the protagonists can best be categorised as “men of letters”, “philosophes“, or “intellectuals”,13 and whether the period in question is best described as “philosophical”, “scientific”, “literary”, or “socio-political”. No lessons have been drawn from the fierce debates over taxonomy since the 1740s, which originated in the fundamental disagreements between the naturalists Carolus Linnaeus (1707–1778) and George-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707–1788) and which still animate geological and medical discussion.14 In other fields, eccentric efforts to identify distinctively “enlightened” features in Joseph Haydn’s (1732–1809) quartets, Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach’s (1714–1788) clavichord music, Allan Ramsay’s (1713–1784) portraits, or Robert Adam’s (1728–1792) buildings have been unconvincing, as have attempts to label particular changes in botanical research, surgical practice, or agricultural machinery.15

Modern Interest

Forceful hostility to ideas associated with Enlightenment thinkers surfaced during the French Revolution , and over the next half century it was vigorously fanned during the Romantic Movement. The Enlightenment has been blamed for almost everything that a writer could disapprove of since the 1780s, from totalitarianism to fascism, capitalist exploitation, nihilism, rampant individualism, the collapse of values, and ecological disasters resulting from attempts to exploit and dominate nature.16 Sexism, racism , religious intolerance, and social exclusion count among its other alleged sins.

Renewed hostility was generated after the two World Wars , when political writers sought causes of the global destruction and deprivation which afflicted most nations. It was never entirely clear, however, who precisely was seeking to explain what to whom and by reference to what, since no careful scholarly enquiry was undertaken. This can be illustrated by the influential and polemical tract Dialektik der Aufklärung (Dialectic of Enlightenment), published in 1944 by two Marxist professors of sociology from Frankfurt, Theodor W. Adorno (1903–1969) and Max Horkheimer (1895–1973) , who were then exiles in the United States. They interpreted the Enlightenment goal to be the subsumption of all particulars under “principles”; mastery of nature was to be secured only if reason was accepted as the court of judgment of calculation.17 Their main thesis was that although social freedom was “inseparable from enlightened thought”, the Enlightenment contained the seeds of its own self-destruction.18 Like subsequent German and French authors, however, such as Michel Foucault (1926–1984) , they relied on many abstract concepts which they projected anachronistically onto 18th-century writings although these concepts could rarely be traced back to them and were unintelligible to readers without their allegiances. Moreover, Adorno and Horkheimer seemed to be ignorant of entirely different ideas and agendas proposed by influential 18th-century writers in France, England, Scotland and elsewhere.

Further hostility was expressed by writers in the 1960s and 1970s, mainly in France and the United States, whose views became labelled as “post-modernist”.19 Once more, none of these writers engaged in deep textual or contextual studies, and none considered any links between political and moral ideas and practices on the one hand and the scientific and technological ideas and resources implemented in varying contexts on the other. Paradoxically, parallels to their own tenets can be readily found in 18th-century writers, such as the centrality of scepticism, the relative nature of judgments and values, the limited roles of reason, and the ineradicable challenges faced, but also posed, by interpretation of evidence and language.

Aristotle (384–322 BC) attended the school of Plato (427–347/348 BC) and later became the teacher of Alexander the Great (356–323 BC). His numerous works are concerned with metaphysics, logic, politics and ethics and have made Aristotle one of the most famous philosophers of ancient Greece. / Aristotle (384–322 BC), Roman copy of a Greek Bronze by Lysippos of Sikyon, marble, around 330 BC, unknown sculptor, photographer: Marie-Lan Nguyen; source: Wikimedia Commons

Interest in 18th-century efforts to understand the rapidly changing and seemingly complex contexts in which people lived, coupled with the question “What can we learn from this?”, has animated multi-disciplinary and inter-disciplinary approaches.20 These studies all reveal subtleties which serve to discourage simplistic generalisations and offer perspectives which inform modern differences. In connection with Adam Smith, for example, and his rival French economists ,21 the relations between laissez-faire approaches and affairs of state, over the status and authority of government and legal institutions, and over the legitimate domains of commercial activities have been studied. Besides, in direct line from late 17th-century and 18th-century discoveries about, and reflections upon, cultural diversities and traditions, debates continue about the defensible temporal and geographical scope of legal, moral, religious, and political views. Claims to universal applicability, intelligibility, and truth are fundamentally challenged by the findings resulting from sceptically based enquiry in all contexts. Moreover, the importance of Aristotle’s (384–322 BC) warning never to ignore the scale of one’s understanding, ambitions or solutions, is increasingly acknowledged.22

Historical Contexts: Science and Religion

The book which René Descartes is holding in his hands contains the words “Mundus est fabula” (the world is a fable). Is this a warning that even the apparently most dependable forms of knowledge may only be a fairy tale invented by man? / Jan Baptist Weenix (1621–1659), Portrait of René Descartes (1596–1650), oil on canvas, 45.1×34.9 cm, ca. 1647–1649; source: © Collectie Centraal Museum

Heavily affected by the civil and revolutionary wars of his time, the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes sought a political order that was arranged according to scientific principles and which would prevent future revolutions. In his works on state theory (De cive, 1642; Leviathan, 1651), he takes as his centre point the endeavour of the human being to maximise happiness and minimise pain. A political system is thus well ordered if it optimises this endeavour. Hobbes contends that the human being is not by origin a social being and, in their natural state, humans are in constant competition (“homo homini lupus”, “bellum omnium contra omnes”). According to Hobbes, this natural state of being could only be overcome by a contract, in which each human relinquishes his original rights to the benefit of the sovereign. If the sovereign were overthrown, the body politic would disintegrate into its individual constituents again; the human returns to its natural state. / William Faithorne? (c. 1620–1691), Thomas Hobbes, etching, 17th century; source: New York Public Library

The French writer and philosopher Voltaire [real name: François Marie Arouet] (1694–1778) enjoyed, as the son of a wealthy notary, a humanist education. In 1719, he came to notice with his first tragedy Œdipe; his epic Henriade (1723) made him famous throughout Europe. In 1726, he fled the threat of arrest to England, where he lived until 1729. He published the Letters concerning the English Nation (1733; the French version, Lettres philosophiques, appeared in 1734) on his stay there. Alongside Montesquieu’s De l’esprit des lois it became the key work of Anglophilia. Following his return, he occupied himself with the study of mathematics and the natural sciences. His Éléments de la philosophie de Newton (1738) made Newton’s cosmology well-known on the continent. Between 1749 and 1753, he lived in Potsdam in response to an invitation from Frederick II., and from 1758 at the Ferney Castle near Lake Geneva. During this period, he published, amongst other works, historical studies and his most famous text Candide ou l’optimisme (1759). / Voltaire [real name: François Marie Arouet] (1694–1778), copperplate engraving, unknown date, unknown artist, scan: Gabor; source: Müller-Baden, Emanuel (ed.): Bibliothek des allgemeinen und praktischen Wissens zum Studium und Selbstunterricht in den hauptsächlichsten Wissenszweigen und Sprachen, Berlin 1905, vol. 5, p. 36, Wikimedia Commons

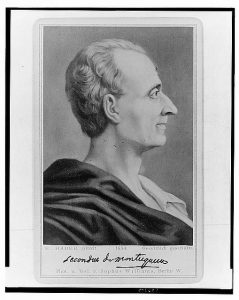

The French political philosopher Charles de Secondat, Baron de la Brède et de Montesquieu (1689–1755) was, following his humanist and legal education, the president of the parlaments of Bordeaux from 1716 to 1726. Afterwards, he travelled throughout Europe, staying in England, and other countries, between 1729 and 1731. In 1748, his opus magnum on political authority De l’esprit des lois appeared, which was of importance for the American constitution as well as that of the French Revolution of 1791, and the doctrine of the separation of powers in general. Many contemporaries perceived De l’esprit des lois as an accurate depiction of the Great Britain’s constitution, and alongside Voltaire’s Lettres philosophiques, it was a key work in continental Anglophilia. / Charles de Secondat, Baron de la Brède et de Montesquieu (1689–1755), photographic print of a portrait by Ernst Hader (1866–1922), 1884, photographed and published by Sophus Williams, Berlin; source: Library of Congress

Almost all thinkers in the 18th century were influenced, however indirectly, by the scientific revolution of the previous century and the legacy of Francis Bacon (1561–1626) , René Descartes (1596–1650) and Isaac Newton (1642–1727) . In addition, the political and philosophical views of Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) and John Locke generated more than a century of responses across Europe. Although these authors were active primarily in Protestant countries, Catholic France became the centre of Enlightened thinking after the 1740s, led by Voltaire (1694–1778) , Charles de Montesquieu (1689–1755) and Denis Diderot (1713–1784) , all of whom admired British thought and political practice.

Since English at that time was understood by few outside Britain, translations were essential if information was to be shared, and these intensified awareness of the complexities of language, meaning, and interpretation which already occupied Biblical scholars. French was the lingua franca among both the intelligentsia and the upper classes, although Latin, unlike Greek, was known to almost all scholars. German, however, was unfamiliar to most outside German territories.23 Nevertheless, the new audiences generated new modes of publication and new modes of reading, ranging from close study to utilitarian modification. Uniform response became increasingly improbable. Socially and politically, it was not new technologies associated with scientific enquiries which caused most anxiety among rulers and ruled alike, it was the scale and rates of change. After all, little had forearmed anyone either to maximize the potential benefits of change, or minimize their potentially harmful consequences.

From the 1690s onwards, sceptics revelled in showing how, in religious contexts, concepts had been stretched to the point of unintelligibility. Their relentless challenges had profound implications. What criteria govern the legitimate modification of a concept? Everyone agreed with Thomas Hobbes that the use of imagination was necessary in framing hypotheses to explain the past or predict the future, but neither task could be separated from appropriately describing and interpreting the present. Yet how could the profligacy of imagination be checked and the advantages of speculation be monitored? Even with appeal to general rules as guide-lines and analogies with previous cases, no general rule decisively settles a new, apparently anomalous case, and no experience warrants a universal claim. Moreover, Hobbes insisted, the ceteris paribus clauses which qualified all legal judgments applied equally in all other branches of enquiry: we never know all the assumptions being made, and the interests of (and technologies available to) a laboratory experimenter are as important as those influencing a translator.24

However, once all this was conceded, the threatening scepticism buried within ancient questions of casuistry could not be avoided: to what extent can generalisations, rules, classifications, or principles be either epistemologically or morally justified? And if appeal to analogy is thereby unavoidable, how are its implications to be assessed? If our structured memories of the past necessarily constrain our understanding of the present, does this have the unpalatable consequence that the past is not a continuously enriched source of reference and comparison, but a progressively obscuring template through which what is new and different can never be grasped?

Censorship , implicit or explicit, was widespread throughout Europe, and unorthodox views were often regarded as seditious – Bacon’s observation that knowledge is power was tacitly accepted by those who sought to secure or retain power. The disguise of discussing one subject whilst meaning another was commonplace, but knowingly made interpretation difficult.25 Some writers further dissembled by following the polemical tradition of referring only to predecessors, whilst remaining silent about contemporaries. In this way, selected works by Montaigne, Descartes, Malebranche or Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle (1657–1757) received continuous attention up to the 1750s although new challenges had risen with the works of Montesquieu, Étienne Bonnot de Condillac (1714–1780) , the Encyclopaedists and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) . All of these continental scholars, and their English predecessors (whose works they openly celebrated), were concerned with method: central topics were evidence, testimony, probability, causation and conceptual change, not least because views about these concepts crucially determined opinions about historical investigation and understanding, alongside those of scepticism, relativism and pragmatism in the investigation of society.26

The philosopher Baruch Spinoza, who is considered one of the pioneers of the Enlightenment and of the historical-critical method of Bible exegesis, is perhaps one of the most famous representatives of Sephardic Judaism. Spinoza’s father moved to Amsterdam in the early 17th century, where Baruch Spinoza was born on November 24, 1632. He received the usual biblical-Talmudic education of the Jewish congregation, but he also began studying scholasticism, ancient languages, the contemporary natural sciences, mathematics, and the philosophical writings of Descartes from an early age. At the age of 23, he was excluded from the Jewish congregation of Amsterdam because he had expressed strong doubts with regard to central Jewish doctrines. In his most important work Ethica, ordine geometrico demonstrata (Ethics, Demonstrated in Geometrical Order, written from about 1662 onward and published posthumously in 1677) he critiques Cartesian dualism. Due to his influential philosophical writings, Spinoza is considered one of the most important thinkers of Western philosophy. / Portrait of Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), oil on canvas, 74.0 × 59.8 cm, between 1675 and 1750, unknown (Dutch or German?) artist; source: © Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel

From the late 17th century onwards, deists and others insisted that the ordinary people’s understanding of religious, scientific, and political views differed widely from that of the original proponents or philosophical commentators.27 The influence of abstract ideas or theories on individual actions was difficult to determine, and those ideas were as likely as others to mutate over time and in ever-changing contexts. The vast majority of European people had never heard of their contemporary intellectuals and encountered their impact, if at all, in such indirect ways as to nullify credit to their originators. It is thus important to determine who valued whom, when, and why. A preacher who forcefully vilified Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) , without having read a word by him, to a congregation for whom the name was unknown, could nevertheless excite lasting negative memories. In the polemical arguments of the period, the use of an author’s name, such as “Cicero” from antiquity or “Newton” among contemporaries, rarely implied agreement even on which works to honour, let alone a detailed analysis – as Ephraim Chambers (ca. 1680–1740) lamented in 1727, only one year after Isaac Newton’s death.28 Throughout the 18th century, the circles of the intellectual elites remained largely self-contained.

Immanuel Kant is considered the most important representative of German Enlightenment philosophy. Influenced by Isaac Newton, John Locke and David Hume, his work focused on the question of the possibility of metaphysical knowledge (Kritik der reinen Vernunft, 1781; Kritik der praktischen Vernunft, 1788; Kritik der Urteilskraft, 1790). He based his system of strict science on the mathematico-physical natural sciences and he criticised the basic principles of traditional metaphysics. Kant established a radical separation of philosophy and theology. He attempted to lay a new foundation for knowledge, morality and faith with his transcendental philosophy. In his search for a reliable justification of morality, he formulated the categorical imperative. / Hugo Bürkner (1818–1897), Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), etching, 1854; source: Bechstein, Ludwig: Zweihundert deutsche Männer in Bildnissen und Lebensbeschreibungen, Leipzig 1854.

In Britain, pragmatism or expediency, readily associated with Baconian or Lockean empiricist attitudes to enquiry and evidence, governed the application of the new sciences to agriculture, mining, or medicine. No one was uniformly sceptical in all contexts, and varieties of sceptical argument were as frequently used to bolster recipes for good living as for subverting rival theological or moral views. Still, metaphysics and abstract speculation were to be avoided, and anyone advocating a “system” was to be treated with suspicion.29 The fierce commercial and political rivalry between Britain and France ensured that the majority of thinkers directed their focus on practical affairs, whether in the scientific or social domain. It was precisely their interest in metaphysics which limited the impact of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) , Christian Wolff (1679–1754) and Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) on British or French Enlightenment thinking, although few of their works were available in accessible French or English translation anyway. The existing translations were invariably interpreted in eccentrically local ways – Hume’s use of the term “mind” became esprit (which may also mean “spirit” or “wit”) in French, and dusha (the equivalent of “soul”) in 19th century Russian translations from the French, thereby almost reversing the original sense.30

However, if the need for action was the ultimate constraint on, or terminus to, philosophical generalisations about knowledge or methods, other constraints have been studied in detail by modern historians. This concerns, for example, the cost and availability of books , and the diverse ways in which they were read, understood, discussed, adapted, or extracted for use;31 the cost, attitude towards, and availability of technologies such as lenses or instruments for measurement, refining metals or the manufacture of industrial machinery;32 or the social and intellectual consequences of economic development, leisure, and consumerism. The latter includes the expansion of libraries, the popularity of public scientific demonstrations, or the cachet of conspicuously owning scientific instruments or attending exhibitions of paintings.33

Even if these social factors generated little self-conscious reflection among the citizens themselves, modern writers began to realize that political or moral generalisations which ignored historical changes and cultural differences, or promoted simplistic explanations, were untenable. It became obvious that increasingly diverse social behaviour threatened the political or theological power bases of those who sought to impose uniformity and unthinking allegiance.34 After the early 1700s, radical writers began to argue that the wealth and health of societies needed to be studied in both literal and metaphorical ways.35 If assumptions, traditions, expectations, behaviour, or conceptual diet were found to damage or threaten that health, then remedial action was necessary – as Pierre Charron (1541–1603) , the pupil of Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) , had already suggested at the end of the 16th century.36

For the majority of practitioners up to the early 1700s, science and religion were still welded seamlessly together. Only a century later, most of the sciences had severed themselves from religion, although forms of deism remained commonplace.37 Theologians of all colours attributed the increasing secularisation of societies not to the rapidly developing sciences, but to an amorphous alliance of atheists, deists, materialists, Epicureans, free-thinkers and sceptics, all of whom were held to subvert the power of the churches. However, promiscuous abuse of either fellow religionists or their critics was strategically self-defeating, because it weakened convictions among enquiring minds.38

Among the most challenging arguments were those of the Huguenot scholar Pierre Bayle, who proposed that it was necessary to separate discussions of behaviour from those of philosophical beliefs: No one regulates their lives entirely in accordance with their professed opinions, and this is because we are all primarily driven or motivated not by reason, but by our passions.39 During the century up to 1789, writers pondered on how such a view might be fully understood, or modified. If its scope was unlimited, covering politics and all social behaviour, as well as all the sciences and religions, what goals could be set or plans implemented to bring about individual freedom and law-bound communities? Moreover, by which criteria could one establish that particular beliefs or other mental events were the causes, however defined, of individual or group actions or events? Furthermore, how reliable were any rules in contexts of uncertainty and constant change if, as the French architect Claude Perrault (1613–1688) had argued forcefully in the 1680s, they were only summaries of past and incomplete understanding?40

In terms of book sales, travel literature, religious tracts, and belles lettres were the most popular genres at the beginning of the 18th century, but the two main sources of information for scholars were learned journals, which summarised and extracted newly published works, and the first encyclopaedias, sometimes called “dictionaries”. These often gave bibliographical references, and readers shamelessly used such entries verbatim in their own writings, without consulting the original texts cited. Challengeable interpretations and unrepresentative quotations thus gained currency by default, especially where theological or political comments were regarded as threatening. The views of Hobbes and Spinoza, for example, and later Bernard de Mandeville (1670–1733) and David Hume, were notoriously distorted in this way. The long preface and many entries in Ephraim Chambers’s Cyclopaedia of 172841 discussed how best to conduct enquiry and communication of its results, as well as issues of classification, evidence, definition and theory.

It should be emphasised here that neither the theory nor the practice of religious toleration was uniformly or consistently embraced throughout Europe in the Enlightenment period. Protestants’ attitudes to Catholics or Jews, for example, Anglicans’ to Dissenters, or Catholics’ to Freemasons or Jesuits typically fell far short of toleration, and fierce disagreement within religious groups, such as Lutherans or Jansenists, about individual rights and duties was commonplace – and arguably as divisive as criticism from outside by free-thinkers, proclaimed atheists, or sceptics.42

Philosophical Methods of Enquiry and Problems

Even in the absence of widely shared views, there was considerable awareness throughout the 18th century of challenges inherited from classical rhetoric.43 Ciceronian ideals, upheld by many among the elite, required speakers and by extension writers to bear in mind the opportunities and limitations of the conceptual and technological resources available to them, as well as the expectations and capacities of their audiences. Any proposed conceptual revision of or challenge to prevailing theological or political views required the greatest care. However, under the general rubric of rhetoric, other matters are of importance.

What counts as an intelligible question and as an acceptable answer to it varies considerably both over time and, at any given time, within different regions, cultural traditions, and disciplines.44 The geologist James Hutton (1726–1797) , for example, realised that almost no one could envisage that small but continuous changes could produce vast changes in land forms, or that “obviously” stable objects such as rocks were themselves subject to constant change, albeit “too slow to be discernible”.45 The capacity for ever more precise measurement was of central importance to the sciences, but it also served to alarm laymen that almost nothing was known about anything, be it very large or very small, very fast or very slow. It also generated the criticism that both value and resources seemed to be allocated only to what could be measured. Furthermore, as early as 1728, Chambers lamented the fact that even people “of the same profession no longer understand one another”.46 Hume’s complaint that most men “confine too much their principles”,47 a commonplace for fifty years already, recorded intellectual gaps in enquiry and comprehension throughout society that were never to be closed.

Whilst the precise nature of “theory”, “principle”, or “system” was almost never clarified by writers of the time, the terms recur throughout the period 1690–1790. Many agreed with Claude Perrault48 that few practitioners thought of themselves as acting under the influence of, or being motivated by a theory, even though it was often useful to generalise particular cases after the event in the form of a theory. As Ephraim Chambers insisted:

[T]he rules of an art are posterior to the art itself, and were taken from it or adjusted to it, ex post facto… dogmatizing and method…are posterior things, and only come in play after the game is started.49

This depiction from the Encyclopédie is the first depiction of a laboratory organized according to scientific principles. The room is populated by a group of researchers which already appears modern. They perform different tasks at different positions: A chemist sitting at the table discusses the production of solutions with a physicist; on the left, a laboratory assistant brings coal from the cellar; and on the right, another laboratory assistant washes vessels. / Chemical laboratory, 1765, unknown artist; source: Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers, Planches, Neuchatel 1765, vol. 33, “Chimie”, Figure I.

The view also emerged that, if empirical enquiries were literally without end, any apparent termini, sometimes misleadingly heralded as axioms, were merely “resting places” before undertaking further research.50 Jean Le Rond d’Alembert’s (1717–1783) masterly summary of these methods in the 1750s underlined the view that only by observation and experiment could theories be justifiably formulated, upheld, revised, or abandoned. Nevertheless, d’Alembert claimed that the ever pressing challenges of new information and constantly changing contexts were such that many problems were simply abandoned as unresolved because they had been replaced by new ones.51

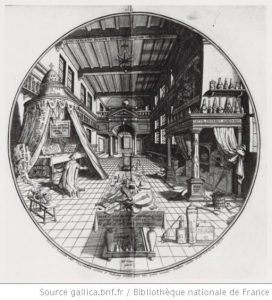

The image shows the alchemistic laboratory of Count Wolfgang II von Hohenlohe at Weickersheim Castle. Test tubes and other vessels are also depicted in this image, but they are placed in an orderly fashion on ledges, shelves and windowsills. Additionally, the alchemist is not handling anything in this depiction. Instead, he is facing the books in a respectful pose. / Paul van den Doort, The laboratory of the alchemist, copperplate engraving, 1609; source: www.gallica.bnf.fr

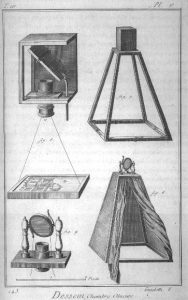

This illustration from the Encyclopédie of 1751 explains in great detail how a camera obscura works and how it can be constructed. It thus attempts to establish a closer connection between theoretical and practical knowledge which was by no means self-evident before the 18th century. / Camera obscura, Drawing, 1751, unknown artist, in: Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, Planches, Neuchatel 1751, vol. III, p. 143 [??], scan: Jean-Jacques MILAN; source: Wikimedia Commons

Increasingly, from the mid-17th century onwards, propagandists and popularisers alike tried to confront the ancient dichotomy between thought and action – or, more precisely, between their texts and the events these recorded in histories or advocated in manifestos. Practising scientists knew well that Thomas Sprat’s (1635–1713) tidy History of the Royal Society of London (1667)52 did not mirror the guesses, inaccuracies and uncertainties of any laboratory . Within a century, however, Diderot and d’Alembert claimed that the texts in the Encyclopédie would more effectively describe the myriad processes appropriate for bettering mankind if they were supplemented by multiple illustrations of techniques and available technologies.

Still, these, too, had to be read and were no more self-evident than any other text. D’Alembert insisted, nevertheless, that there were countless human activities for which “showing” is essential and never fully matched by “saying”53 – when, for example, we witness the skills of a surgeon, needlewoman, or ploughman, or those of a sculptor or harpsichordist. Craftsman skills, in this sense, can only be learned on the job, and the tacit knowledge of “know-how” among practitioners cannot be acquired from texts alone. This fact became a source of irritation and then resignation among artists and musicians towards the end of the 17th century, when the rapidly expanding class of leisured bourgeois consumers urgently sought advice on what to acquire as emblems of their wealth and taste.

Critics and commentators who promoted themselves as guides soon found that their audience was not interested in the techniques and processes of painting or composition. Learning what to say and what property to buy was enough.54 More pretentious critics offered theoretical discussions about aesthetics from which practising artists themselves, with a few notable exceptions such as William Hogarth (1697–1764) and Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) in England, absented themselves. Such critics frequently diverted attention away from their supposed subject matter, the works themselves, in favour of a spectator’s self-conscious experiences, thereby contributing to what many already regarded as the tyranny of the text.55 Moreover, the more the works of scientists, architects or musicians were heralded by the ignorant public, even if they were neither understood nor upheld by the tests of time, the more the performers themselves withdrew into self-contained professions, often resenting the supposedly parasitic critics who claimed special insights. Precisely who the “public” were (and which rights, duties, or competencies could be associated with them) was increasingly debated throughout the 18th century.56

The Scottish clergyman, rector of the University of Edinburgh (1762–1792) and a key representative of the Scottish enlightenment, William Robertson (1721–1793) was one of the most widely-read historians of the 18th century (The history of Scotland, 1759; The history of the reign of the Emperor Charles V, 1769; History of America, 1777). Establishing the divide between profane and Church history, he replaced the insular perspective of English historiography with a Euro-centric approach. He his counted amongst the founders of modern academic history. / William Robertson (1721–1793), etching following a contemporary oil painting, 1777, artist unknown; source: Robertson, William: The history of America, Leipzig 1777.

From the outset of the century, prompted by the rapid expansion of experiments within the sciences and the irresistible popularity of traveller’s tales of exotic peoples, it was becoming commonplace for thinkers such as Hume to warn against inventing explanations in terms of “causes which never existed” or projecting onto the past (or even on other cultures in the present) anachronistic interpretations drawn from the context of the commentator alone: “[I]t seems unreasonable to judge of the measures, embraced during one period, by the maxims, which prevail in another.”57 Such views, propounded for example by Adam Ferguson (1723–1816) and William Robertson (1721–1793) in Scotland, drew attention to the problem that since a search for causes characterised much enquiry, there needed to be agreement on how to identify the events, processes, or actions to be explained. What were the boundaries of a given event, such that its causes and consequences can be separately identified? Moreover, if each event was ultimately held to be unique, at least with regard to its spatio-temporal context, how can events be legitimately classified together or even fruitfully discussed? Throughout the 17th century, it had increasingly been argued that identity and difference can be determined only by means of analogy and comparison – each of which was qualified by degree. Comparison requires a context and consideration of the various relations in which the elements are to be linked.

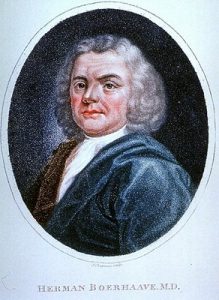

Herman Boerhaave was the most famous medical teacher of early 18th-century Europe. He is widely regarded as the founder of clinical teaching; however, when Boerhaave was in charge of clinical teaching at Leiden the beds in the collegium medico practicum were empty most of the time. In fact, in the period between 1711 and 1737, during Boerhaave’s most successful years, there was a serious decline in the number of patients admitted to the hospital. Boerhaave’s successful approach, the reason why he was eventually called the teacher of Europe (amongst his most famous pupils was Albrecht von Haller), was pedagogical. He did not discover anything new, but he was extremely good at keeping and transforming existing knowledge in a new and more easily consumable format. / J. Chapman, Portrait of Herman Boerhaave (1668–1738), 1798; source: U.S. National Library of Medicine

Just as the ancient search for a criterion of knowledge continued into the 18th century, so did debate about the universal or contingent validity of knowledge claims. Many of the rapidly developing physical sciences aimed to present their conclusions in a mathematized form, hoping thereby to convey a priori certainty and universality.58 Nevertheless, where such a formulation seemed to be unavailable and variable experiments undeniable, the provisional and revisable character of conclusions could not be disguised. From the early 1700s onwards, initially in Leiden and associated with the work of Herman Boerhaave (1668–1738) , it was found that many of the assumptions and theories about inert matter that held sway in physics and chemistry were inapplicable in the life and biological sciences.59 Generally, multiple causation and reciprocal inter-action seemed to be at work in living systems and in complex bodies: the chemical model of analysing matter into constituent elements before synthesising the findings did not capture the nature of the observable dynamic processes and relations.60 And whilst many thoughtful medical practitioners concentrated on the “how” of processes rather than the “why”, the unpredictability of most diseases and illnesses, coupled with continuous change both in living things and in the observer’s understanding of them, forced them to admit the provisionality of all knowledge claims.

Such views encouraged a number of experimenters and practitioners in the life sciences to challenge the inherited binary system of thought.61 Findings of apparent complexity, ambiguity and paradox suggested to them that attempts to reduce all statements to one of a binary pair overlooked matters which revealed an irreducible vagueness or indeterminacy. Many philosophers such as Descartes, Fontenelle, George Berkeley (1685–1753) , Hume and Diderot experimented with the dialogue form. They thus echoed ancient attempts to capture in texts the dynamics and improvisatory dimensions of conversation, in which participants can explore, modify, and play with ideas without goals of final conclusion – other than those of pragmatic need. Early scientific writing in the mid-17th century adopted a conversational style, partly to convey the processes of experiment and partly to defuse hostility from strident theologians – even though most European scientists associated themselves with current theological views.

The adversarial mode of legal argument and the rigorous Jesuit tradition of combative discussion sought victory by fair means or foul, rather than approximations to the truth or moderation of judgment. In spite of these drawbacks, and with varying degrees of reluctance, Scottish writers such as Hume, Adam Ferguson and William Robertson acknowledged that there was a deep social and psychological problem: few people were inspired by moderation, and almost no one was galvanised by it to tenacious action. Everyone seeking power readily grasped that the forceful presentation of simplified views, however misleading, secured more attention and could be used to motivate more people than any cautious warnings of complexity or ignorance. As many ancient commentators noted, skilful orators could easily arouse crowds by using slogans and other theatrical devices, but they could rarely do so by cautious analysis of ideas or possibilities.

Civil Society

The Dutch scholar of law Hugo Grotius is considered the founder of classical international law, which he developed in his works (in particular De jure belli ac pacis, 1625) from principles of natural law as a part of the positive and reason-bound legal order encompassing all states and all people. Grotius thus placed international law on the basis of equality between states and mutuality. Grotius’s theories were first applied in practice in the Peace of Westphalia (1648). / Willem Jabszoon Delff (1580–1638), portrait of Hugo Grotius (1583–1645), copper engraving after a painting by Michiel van Mierevelt (1567–1641), 1632; source: Grotius, Hugo: De Iure Belli ac Pacis, Libris Tres…, Amsterdam 1641 [title engraving].

From the 1680s onwards it was widely agreed, in both France and Britain, that man was a fundamentally social being, although what that was held to mean varied greatly. Interest in social structures and arrangements seemed to presuppose a study of man himself – “la science de l’homme” (the French phrase of the 1680s), which was boldly promoted by David Hume who based his account on traditional distinctions between sensory experience, the imagination, and the rational intellect. This required an analysis both of man’s mental and physical make-up, only nervously acknowledging any relevant ideas from medicine and the life sciences, and of man-made institutions such as the law and government. Aristotle’s insistence that studying a thing in isolation was inadequate for understanding but must be supplemented by examination of its manifold relations to others things and processes was increasingly heeded outside religious contexts. It has been observed that Scottish writers in particular adapted established vocabulary from theologians, jurists and philosophers to their perceived needs, drawing on earlier Continental theorists of law such as Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) and Pufendorf.62

If society was an aggregate of human animals, perhaps social institutions and practices, such as politics, the law, and religion, could be analogically explained in medical terms, rather than in a vocabulary appropriate for inert matter. Primarily a medical concept at the time, “sympathy” became a prominent concept for Hume and Adam Smith, and the multiple factors suggested as influencing an individual’s health63 were readily extended to society at large. This entailed that political and social explanations or agendas became ineradicably contextual and historically anchored to the evolution of practices and concepts that each had inherited. In the field of medicine, the views of Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709–1751) or Claude-Adrien Helvetius (1715–1771) on biological issues slowly gained professional support, although to most laymen they were as inaccessible as the earlier mathematically grounded theses of Newton. Leading citizens were primarily concerned with the effective application of scientific ideas to practical life.

The rapid growth of the British market economy from the 1690s and its attendant consumerism were accompanied by widespread interest in Locke’s arguments about personal and property rights. Central social and political questions concerned the relations between liberty and authority, egoism and social order. Law was held to be the stabilising factor and guarantor of limited toleration. “Sociability”, never unequivocally defined, was a goal of education and individual fulfilment for every writer from Anthony Ashley Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury (1671–1713) to Adam Smith, and emphasis on “politeness” readily appealed to the elite in France who had been heralding “politesse” as a social cement for a century.64 The French concept itself, however, traded on a strenuously protected concept of “trust” which, as European elites painfully discovered, was neither widely understood nor implemented in societies at large.65 And if those same elites shared Voltaire’s view that “The thinking Part of Mankind are confin’d to a very small number”,66 Allan Ramsay’s version had obvious political implications:

[T]he business of the bulk of mankind is not to think, but to act, each in his own little sphere, and for his own purposes; and, this he may do, very completely, without much reflection.67

Such reflections seemed to imply that if the practicalities of government are immeasurably hindered when more citizens are enabled to think, the moral burdens are immeasurably increased when they do not.

An additional factor, which had again been inherited from classical rhetoric, was prominently heralded by Hume and others: for many people, the final preference for an idea, argument, or doctrine did not rest on the intellectual content, rigour, implications, or scope of their presentation, but on aesthetic judgments about style – taste is often the ultimate arbiter.68 This partly explained that “the public” was willing to tolerate, however fleetingly, the simplistic slogans or banners of theatrical orators, the meaning of which was deceitfully held to be self-evident, even to the most limited minds.

Political Economy

Reflections on civil society from the 1680s onwards, particularly in Britain and France, generated interest in “political economy” which was understood as the interaction of, and arguably inextricable link between, economic and political issues in societies whose concepts were evolving as rapidly as the structures of societies themselves. The goal of political economy was the “improvement” of man’s lot, which was often misunderstood as only material betterment, but more properly as the “health and wealth of the nation”. By the mid-18th century, rival interpretations by David Hume, Adam Smith and Sir James Steuart (1712–1780) in Scotland, or by French writers such as François Quesnay (1694–1774) and Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot (1727–1781) , nevertheless anchored their views to epistemological tenets about probability and the absence of certainties, alongside analyses of man’s social nature, moral understanding, and political structures. This connection with views about the nature of knowledge and its acquisition was gradually abandoned by later writers on political and economic issues.

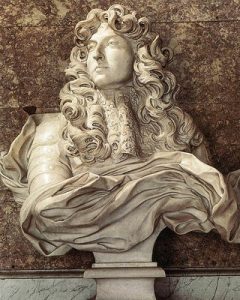

Louis XIV, who occupied the French throne from 1643 to 1715, went down in history as the “Sun King”. During his reign he made his court at Versailles into a model which many European rulers sought to emulate. However, his efforts to achieve a European hegemony also contributed to the fact that European politics in the late 17th and early 18th century were dominated by warfare. The so-called “Grand Alliance” formed in 1686 at Augsburg by the Emperor, Spain, Sweden, Saxony, Bavaria, the Palatinate and a number of smaller powers was designed to prevent further French expansion, either through diplomacy or by force. / Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), bust of Louis XIV (1638–1715), white marble, 1665, location of the original: Diana Salon, Versailles, photographer: Louis le Grand, 2006; source: Wikimedia Commons

Power has always been dependent on wealth, which rested in turn on whatever resources could be enhanced or exploited to secure it – including taxes, confiscation, exploration, trade, land and people. Louis XIV’s (1638–1715) ministers had been analysing in the 1660s how and why Florentine city states had flourished in the 15th and 16th centuries, which led to significant government support for what was essentially the defence budget – the physical needs of armies and institutions committed to the imperial ambitions of their leaders, such as instruments of measurement, engineering projects, or transport.69 It was suggested that if France could intellectually outbalance its main rival Britain, its own wealth and health – and European, if not also global domination – might be secured. Whilst both technological developments and trading secrets were protected everywhere, the spread of competitive commercial activity throughout the 18th century accelerated awareness that ideas, as such, could not be owned and were always susceptible to change and improvement.

Conclusion

Throughout history, conceptual repertoires and boundaries, professional traditions, goals and agendas, and normative allegiances have been jealously guarded. Practising scientists typically pay little attention to the histories of their disciplines, methods and concepts, but most are aware of the underdetermined character of their written reports. After all, these can neither be understood nor replicated, even by fellow experts, without additional information about the context which covers, for example, the constraints, technologies, and resources in operation. By contrast, historians of science, medicine, engineering or agriculture are alert to the importance and affordability of laboratory, experimental or field equipment, such as microscopes or measuring instruments, but there has been limited study of the economic and artistic consequences of technological features in the theatre, such as scenery, acoustics, lighting, and instrument design.70

Those who have limited their focus to “theory”, “ideas”, “concepts” or “arguments” – whether philosophical, political, legal or theological – typically dismiss as irrelevant how such ideas have been (or, indeed, provably could be) implemented in the messy, complex contexts of the real world. Thereby they prolong the established hostility between practitioners and commentators. It is as important to examine the manner in which scientific practices and claims have been used to bolster or discredit particular cultures as it has been to analyse the impact of religious and political views. The “cognitive content” of philosophical or scientific claims (however it is identified) is not the same as their social or cultural sources or implications. Moreover, there is no field of enquiry that does not use ideas and methods which originated in other, unrelated areas: the implications of such legacies, if undetected, can seriously impede understanding. Concepts are tools, humanly devised for contextually anchored tasks. If the contexts change, the tools must be re-shaped or abandoned, but obsolescent concepts always embody useless and often obstructive elements.

Concepts of law, liberty, interest, property, or revolution oscillate as much over time in their scope and use as do those of knowledge, truth, or reality. Awareness of conceptual variation and change, under different conditions, calls for sustained multi-disciplinary study, alongside the analysis of technologies and prevailing scientific views on behaviour and mind-sets. An individual’s views about medicine in general or health in particular, for example, may influence his or her behaviour towards family, property, societal responsibilities or the future. Besides, the concepts used may change during the course of a life, generating obstacles to both self-knowledge and understanding by others. Historical research, hermeneutics and reception studies have merely confirmed that individuals cannot reliably identify and separate themselves from their interests, knowledge, agendas and cultural contexts, in order to make judgments of universal validity or scope.

The use of “Enlightenment” as a description of either a period of time or sets of ideas and practices may well diminish in value as detailed enquiry delves into the thought and action of earlier times. The categories and taxonomies chosen by historians neither record abstract eternal essences, nor do they celebrate immunity from revision or abandonment. Naturally, in the 18th century, no one could foresee the scale or implications of the industrial revolution , scientific understanding, or technological opportunities, of national or global trends in population, of social or political changes, of the consequences of educational reforms and global communication, or of the manic ambitions of those seeking power.

Appendix

Sources

Académie Française (ed.): Dictionnaire de l’Academie Franҫoise, 5th ed., Paris 1813 [1694], vol. 1–2, 1st ed. online: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k503971 (vol. 1) and http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k50398c (vol. 2) [27/05/2013].

Adorno, Theodor W. / Max Horkheimer: Dialektik der Aufklärung: Philosophische Fragmente, Amsterdam 1944 [English translation: Dialectic of Enlightenment, transl. by John Cumming, London 1973].

[Arnauld, Antoine / Nicole, Pierre]: La Logique ou l’art de penser, Paris 1763 [Amsterdam 1697], online: http://archive.org/details/lalogiqueoulart00arnagoog [27/05/2013].

Bailey, Nathan: Dictionarium Britannicum: Or a More Compleat Universal Etymological English Dictionary than any Extant, London 1730.

Bayle, Pierre: Dictionnaire Historique et Critique, 3rd ed., Rotterdam 1720 [1697], vol. 1–4, 1st ed. online: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k50432q [27/05/2013].

idem: Œuvres Diverses, The Hague 1727–1731.

Berkeley, George: The Works of George Berkeley, Bishop of Cloyne, ed. by Thomas Edmund Jessop et al., London 1948–1957, vol. 1–9.

Boyer, Abel: Le Dictionnaire Royal François-Anglois et Anglois-François, London 1756 [1699], vol. 1–2.

Buffon, George Louis Leclerc de: Œuvres Philosophiques de Buffon, ed. by Jean Piveteau, Paris 1954.

Burke, Edmund: Reflections on the Revolution in France, ed. by J.C.D. Clarke, Stanford 2001.

Burney, Charles: A General History of Music: From the Earliest Ages to the Present Period (1789), ed. by Frank Mercer, London 1957, vol. 1–2.

Carré, J.-R: La Philosophie de Fontenelle, Paris 1932.

Cassirer, Ernst: Die Philosophie der Aufklärung, Tübingen 1932 [English translation: The Philosophy of the Enlightenment, transl. by Fritz C.A. Koelln, Princeton 1951].

Chambers, Ephraim: Cyclopaedia or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 2nd ed., London 1738 [1728], vol. 1–2, 1st ed. online: http://archive.org/details/Cyclopediachambers-Volume1 and http://archive.org/details/Cyclopediachambers-Volume2 [27/05/2013].

Charron, Pierre: Of Wisdome three bookes, transl. by Samson Lennard, London 1640 (1608).

Condillac, Etienne Bonnot de: Œuvres Philosophiques de Condillac, ed. by Georges Le Roy, Paris 1947, vol. 1–3.

Diderot, Denis et al. (eds.): Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, Paris 1751–1780, vol. 1–35, online: http://portail.atilf.fr/encyclopedie/ [29/07/2013].

Dubos, Jean-Baptiste: Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et la peinture, Paris 1719, vol. 1–2, vol. 2 online: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k62795731 [27/05/2013].

Ferguson, Adam: An Essay on the History of Civil Society, ed. by Duncan Forbes, Edinburgh 1966.

Fontenelle, Bernard le Bovier de: Œuvres diverses, The Hague 1728, vol. 1–3.

Girard, Gabriel: Synonymes françois, leurs différentes significations: Le choix qu’il en faut faire pour parler avec justesse, ed. by Nicolas Beauzée, Paris 1780 [1769], vol. 1–2, 1st ed. online: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k506281 (vol. 1) and http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k730600 (vol. 2) [27/05/2013].

Gregory, John: A Comparative View of the State and Faculties of Man with those of the Animal World, Dublin 1774 [1768], online: http://archive.org/details/acomparativevie02greggoog [18/06/2013].

Hobbes, Thomas: The Elements of Law Natural and Politic, ed. by J.C.A. Gaskin, Oxford 1994, online: http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/Hob2Ele.html [18/06/2013].

Howell, James: A French and English Dictionary, composed by Mr Randle Cotgrave, London 1661.

Hume, David: An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding, ed. by Tom L. Beauchamp, Oxford 2000.

idem: Essays Moral Political and Literary, ed. by Eugene F. Miller, Indianapolis 1985.

idem: The History of Great Britain, London 1770, online: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015073721493 [18/06/2013].

idem: The Letters of David Hume, ed. by J.Y.T. Greig, Oxford 1932.

idem: A Treatise of Human Nature, ed. by David Fate Norton et al., Oxford 2007.

Hutton, James: An Investigation of the Principle of Knowledge, London 1794.

Johnson, Samuel: A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words are Deduced from Their Originals, Explained in their Different Meanings, 9th ed., London 1805.

King, William: An Essay on the Origin of Evil, transl. and ed. by Edmund Law, 3rd ed., Cambridge 1739.

La Mettrie, Julien Offray de: Œuvres Philosophiques, Berlin 1775.

[Le Rond d’Alembert, Jean]: Mélanges de littérature, d’histoire, et de philosophie, Amsterdam 1770, vol. 1–5.

Lord Kames [Henry Home]: Elements of Criticism, ed. by Peter Jones, Indianapolis 2005, vol. 1–2.

Mandeville, Bernard: The Fable of the Bees, or, Private Vices, Publick Benefits, ed. by F.B. Kaye, Oxford 1924.

Morin, Benoît (ed.): Dictionnaire universel des synonymes de la langue française: Contenant les synonymes de Girard, indiques par le Grand-Maître de l’Université de France pour l’usage des collèges et ceux de Beauzée, Roubaud, Dalembert, Diderot et autres écrivains célèbres, Paris 1818, vol. 1–2.

[Panckoucke, André Joseph]: Dictionnaire des proverbes François, Et Des Façons De Parler Comiques, Burlesques Et Familières, etc.: Avec L’Explication, Et Les Etymologies Les Plus Avérées, Paris 1749, online: http://archive.org/details/dictionnairedes02pancgoog [27/05/2013].

Perrault, Claude: Les Dix Livres D’Architecture De Vitruve: Corrigez Et Tradvits nouvellement en François, avec des Notes & des Figures, 2nd ed., Paris 1684 [1673], 1st ed. online: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k85660b [18/06/2013].

idem: Ordonnance for the Five Columns After the Method of the Ancients, transl. by Indra Kagis McEwen, ed. by Alberto Pèrez-Gómez, Santa Monica 1993.

Perronet, Jean-Rodolphe: Description Des Projets Et De La Construction Des Ponts De Neuilli, De Mantes, D’Orléans, De Louis XVI, etc. …, 2nd ed., Paris 1788 [1782].

Quesnay, Franҫois: Franҫois Quesnay et la Physiocratie, Paris 1958.

Ramsay, Allan: Dialogue on Taste, in: The Investigator 322 (1755), 2nd ed., London 1762, pp. 1-77.

Robertson, William: The History of America, Dublin 1777, online http://hdl.handle.net/2027/ucm.5319463420 [18/06/2013].

idem: The Works of William Robertson, To Which is Prefixed, an Account of the Life and Writings of the Author, ed. by Dugald Stewart, London 1840, vol. 1–8.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques: Œuvres Complètes, ed. by Bernard Gagnebin et al., Paris 1959–1995, vol. 1–5.

Smith, Adam: Essays on Philosophical Subjects: Account of the Life and Writings of Adam Smith, LL.D., ed. by William P.D. Wightman et al., Glasgow 1980.

idem: The Theory of Moral Sentiments, ed. by David D. Raphael et al., Oxford 1976.

Sprat, Thomas: History of the Royal-Society of London for the Improving of Natural Knowledge, London 1667, online: http://archive.org/details/historyroyalsoc00martgoog [19/06/2013].

Steuart, Sir James: An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Oeconomy, ed. by Andrew S. Skinner, Edinburgh 1966.

Turgot, Anne-Robert-Jacques: Réflexions sur la formation et la distribution des richesses, Paris 1766, online: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8625609f [19/06/2013].

Voltaire: Philosophical Letters, transl. by Ernest Dilworth, New York 1961.

Bibliography

Alder, Ken: Engineering the Revolution: Arms and Enlightenment in France, 1763–1815, Princeton 1999.

Arthur, W. Brian: The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves, London et al. 2009.

Bayly, Christopher A.: The Birth of the Modern World 1780–1914, London et al. 2004.

Berman, David: A History of Atheism in Britain: From Hobbes to Russell, London 1990.

Berry, Christopher J.: The Idea of Luxury: A Conceptual and Historical Investigation, Cambridge 1994.

Bianconi, Lorenzo et al. (eds.): Opera Production and Its Resources, Chicago 1998.

Blunt, Wilfrid: The Compleat Naturalist: A Life of Linnaeus, London 1971.

Bongie, Laurence L.: David Hume: Prophet of the Counter-Revolution, Oxford 1965.

Bremner, David: The Industries of Scotland: Their Rise, Progress, and Present Condition, Edinburgh 1869.

Brett, Annabel et al. (eds.): Rethinking the Foundations of Modern Political Thought, Cambridge 2006.

Brooke, John Hedley: Science and Religion: Some Historical Perspectives, Cambridge et al. 1991.

Bud, Robert et al. (eds.): Instruments of Science: An Historical Encyclopedia, London et al. 1998.

Christensen, Thomas: Rameau and Musical Thought in the Enlightenment, Cambridge 1993.

Clark, Peter: British Clubs and Societies 1580–1800: The Origins of an Associational World, Oxford et al. 2000.

Cranston, Maurice: Philosophers and Pamphleteers: Political Theorists of the Enlightenment, Oxford et al. 1986.

Craveri, Benedetta: La civiltà della conversazione, Milan 2001.

Crow, Thomas E.: Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Paris, New Haven et al. 1985.

Daiches, David et al. (eds.): A Hotbed of Genius: The Scottish Enlightenment, 1730–1790, Edinburgh 1986.

Darnton, Robert: The Forbidden Best-Sellers of Pre-Revolutionary France, London 1996.

idem: The Devil in the Holy Water or the Art of Slander from Louis XIV to Napoleon, Philadelphia 2010.

Daumas, Maurice: Scientific Instruments of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries and Their Makers, London 1972.

Doig, Andrew et al.: William Cullen and the Eighteenth Century Medical World: A Bicentenary Exhibition and Symposium Arranged by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh in 1990, Edinburgh 1993.

Donovan, Arthur L.: Philosophical Chemistry in the Scottish Enlightenment: The Doctrines and Discoveries of William Cullen and Joseph Black, Edinburgh 1975.

Ehrard, Jean: L’idée de nature en France dans la première moitié du XVIIIe siècle, Paris 1963, vol. 1–2.

Emerson, Roger L.: Essays on David Hume, Medical Men and the Scottish Enlightenment: Industry, Knowledge and Humanity, Farnham et al. 2009.

Fitzpatrick, Martin et al. (eds.): The Enlightenment World, London 2004.

Fontana, Biancamaria (ed.): The Invention of the Modern Republic, Cambridge 1994.

Force, James E. et al. (eds.): Essays on the Context, Nature and Influence of Isaac Newton’s Theology, Dordrecht 1990.

Forsyth, Michael: Buildings for Music: The Architect, the Musician, and the Listener from the Seventeenth Century to the Present Day, Cambridge 1985.

Fox, Celina: The Arts of Industry in the Age of Enlightenment, New Haven et al. 2009.

Fox, Robert et al. (eds.): Luxury Trades and Consumerism in Ancien Régime Paris: Studies in the History of the Skilled Workforce, Aldershot 1998.

France, Peter: Rhetoric and Truth in France: Descartes to Diderot, Oxford 1972.

Fubini, Enrico: Music and Culture in Eighteenth-Century Europe: A Source Book, Chicago 1994.

Gay, Peter: The Enlightenment: An Interpretation, London 1966–1969, vol. 1–2[MC95] .

Gillispie, Charles Coulston: The Edge of Objectivity: An Essay in the History of Scientific Ideas, Princeton 1960.

Glass, Bentley et al. (eds.): Forerunners of Darwin 1745–1859, Baltimore 1959.

Glaziou, Yves: Hobbes en France au XVIIIe siècle, Paris 1993.

Gleeson, Janet: The Moneymaker, London 1999.

Goldgar, Anne: Impolite Learning: Conduct and Community in the Republic of Letters 1680–1750, New Haven et al. 1995.

Golinski, Jan: Science as Public Culture: Chemistry and Enlightenment in Britain, 1760–1820, Cambridge 1992.

Goodman, Dena: The Republic of Letters: A Cultural History of the French Enlightenment, Ithaca 1994.

Gordon, Daniel (ed.): Postmodernism and the Enlightenment: New Perspectives in Eighteenth-Century French Intellectual History, London 2001.

Grell, Ole Peter et al. (eds.): Toleration in Enlightenment Europe, Cambridge 2000.

Gusdorf, Georges: Les sciences humaines et la pensée occidentale, Paris 1966–1973, vol. 6: L’avènement des sciences humaines au siècle des lumières.

Haakonssen, Knud (ed.): The Cambridge History of Eighteenth-Century Philosophy, Cambridge 2006.

idem (ed.): Enlightenment and Religion: Rational Dissent in Eighteenth-Century Britain, Cambridge 1996.

Hahn, Roger: The Anatomy of a Scientific Institution: The Paris Academy of Sciences, 1666–1803, Berkeley 1971.

Hankins, Thomas L.: Science and the Enlightenment, Cambridge 1985.

Harman, Peter M.: The Culture of Nature in Britain 1680–1860, New Haven et al. 2009.

Harrington, Kevin: Changing Ideas on Architecture in the Encyclopédie, 1750–1776, Ann Arbor 1981.

Heartz, Daniel: Music in European Capitals: The Galant Style 1720–1780, London 2003.

Herries Davies, Gordon L.: The Earth in Decay: A History of British Geomorphology 1578–1878, New York 1969.

Hill, Peter P.: French Perceptions of the Early American Republic 1783–1793, Philadelphia 1988.

Holub, Robert C.: Reception Theory: A Critical Introduction, London et al. 1984.

Hont, Istvan: The Jealousy of Trade: International Competition and the Nation-State in Historical Perspective, Cambridge, MA 2010.

Howell, Wilbur Samuel: Eighteenth Century British Logic and Rhetoric, Princeton 1971.

Hundert, E.J.: The Enlightenment’s Fable: Bernard Mandeville and the Discovery of Society, Cambridge 1994.

Hunter, Michael et al. (eds.): Atheism from the Reformation to the Enlightenment, Oxford 1992.

Israel, Jonathan: Enlightenment Contested: Philosophy, Modernity, and the Emancipation of Man 1670–1752, Oxford 2006.

idem: Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity, 1650–1750, Oxford 2001.

Jacob, Margaret C.: Living the Enlightenment: Freemasonry and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Europe, New York 1991.

idem: The Radical Enlightenment: Pantheists, Freemasons and Republicans, London 1981.

Jardine, Nicholas: The Scenes of Inquiry: On the Reality of Questions in the Sciences, Oxford 1991.

Johnson, James H.: Listening in Paris: A Cultural History, Berkeley 1995.

Johnson, Victoria et al. (eds.): Opera and Society in Italy and France from Monteverdi to Bourdieu, Cambridge 2007.

Jones, Peter: Hume’s Sentiments: Their Ciceronian and French Context, Edinburgh 1982.

idem: The Reception of David Hume in Europe, London et al. 2005.

Kaviraj, Sudipta et al. (eds.): Civil Society: History and Possibilities, Cambridge 2001.

Kelley, Donald R.: Faces of History: Historical Inquiry from Herodotus to Herder, New Haven et al. 1998.

idem: Fortunes of History: Historical Inquiry from Herder to Huizinga, New Haven et al. 2003.

Keohane, Nannerl O.: Philosophy and the State in France: The Renaissance to the Enlightenment, Princeton 1980.

King, Lester S.: The Philosophy of Medicine: The Early Eighteenth Century, Cambridge, MA 1978.

Kors, Alan Charles: Atheism in France, 1650–1729, Princeton 1990.

Koselleck, Reinhart: The Practice of Conceptual History: Timing History, Spacing Concepts, transl. by Todd Samuel Presner et al., Stanford 2002.

Kühn, Manfred: Kant: A Biography, Cambridge 2001.

Lindberg, David C. et al. (eds.): Reappraisals of the Scientific Revolution, Cambridge 1990.

Link, Dorothea: The National Court Theatre in Mozart’s Vienna: Sources and Documents, 1783–1792, Oxford 1998.

Macmillan, Duncan: Painting in Scotland: The Golden Age, Oxford et al. 1986.

Mainstone, Rowland J.: Developments in Structural Form, 2nd ed., London 1998.

Mayr, Ernst: Systematics and the Origin of Species: From the Viewpoint of a Zoologist, New York 1942.

McClellan III, James E.: Science Reorganized: Scientific Societies in the Eighteenth Century, New York 1985.

Melton, James van Horn: The Rise of the Public in the Enlightenment, Cambridge 2001.

Montandon, Alain: Dictionnaire Raisonné de la Politesse et du Savoir-Vivre: Du moyen âge à nos jours, Paris 1995.

Morrison-Low, A.D: Making Scientific Instruments in the Industrial Revolution. Surrey 2007.

Morton, Alan Gilbert: History of Botanical Science: An Account of the Development of Botany from Ancient Times to the Present Day, London 1981.

Mumford, Lewis: Technics and Civilization, London 1934.

Norton, David et al. (eds.): The Cambridge Companion to Hume, 2nd ed., Cambridge 2009.

Olson, Richard: Science Deified & Science Defied: The Historical Significance of Science in Western Culture, Berkeley 1982–1990, vol. 1–2.

Oz-Salzberger, Fania: Translating the Enlightenment: Scottish Civic Discourse in Eighteenth-century Germany, Oxford 1995.

Panofsky, Erwin: Renaissance and Renascenes in Western Art, Copenhagen 1960.

Picon, Antoine: French Architects and Engineers in the Age of Enlightenment, Cambridge 1992.

Pocock, John G. A.: Virtue, Commerce, and History: Essays on Political Thought and History, Chiefly in the Eighteenth Century, Cambridge 1985.

Poovey, Mary: A History of the Modern Fact: Problems of Knowledge in the Sciences of Wealth and Society, Chicago 1998.

Porter, Roy (ed.): The Cambridge History of Science, vol. 4: Eighteenth-Century Science, Cambridge 2003.

idem et al. (ed.): The Enlightenment in National Context, Cambridge 1981.

Porter, Roy: English Society in the Eighteenth Century, London 1982.

Radice, Mark A. (ed.): Opera in Context: Essays on Historical Staging from the Late Renaissance to the Time of Puccini, Portland 1998.

Reesink, Hendrika Johanna: L’Angleterre et la littérature anglaise dans les trois plus anciens périodiques français de Hollande de 1684 à 1709, Paris 1931.

Rex, Walter: Essays on Pierre Bayle and Religious Controversy, The Hague 1965.

Richter, Melvin: The History of Political and Social Concepts: A Critical Introduction, Oxford 1995.

Riskin, Jessica: Science in the Age of Sensibility: The Sentimental Empiricists of the French Enlightenment, Chicago 2002.

Rivers, Isabel (ed.): Books and their Readers in Eighteenth-Century England: New Essays, London et al. 2001.

idem: Reason, Grace, and Sentiment: A Study of the Language of Religion and Ethics in England, 1660–1780, Cambridge 1991–2000, vol. 2: Shaftesbury to Hume.

Robertson, John: The Case for the Enlightenment: Scotland and Naples 1680–1760, Cambridge 2005.

Roche, Daniel: Le siècle des lumières en province: Académies et académiciens provinciaux, 1680–1789, Paris 1978, vol. 1–2.

idem: France in the Enlightenment, Cambridge, MA 1998.

Roger, Jacques: Les Sciences de la Vie dans la pensée franҫaise du XVIIIe siecle: La génération des animaux de Descartes à l’Encyclopédie, Paris 1963.

Rothschild, Emma: Economic Sentiments: Adam Smith, Condorcet, and the Enlightenment, Cambridge, MA 2001.

Rowland, Keith T.: Eighteenth Century Inventions, New York 1974.

Rudwick, Martin J.S.: Bursting the Limits of Time: the Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Revolution: Based on the Tarner Lectures Delivered at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1996, Chicago 2005.

Rykwert, Joseph: The First Moderns: The Architects of the Eighteenth Century, Cambridge, MA 1983.

Sadie, Julie Anne (ed.): Companion to Baroque Music, Oxford 1998.

Saint, Andrew: Architect and Engineer: A Study in Sibling Rivalry, New Haven et al. 2007.

Sale, Kirkpatrick: Human Scale, New York 1980.

Sargentson, Carolyn: Merchants and Luxury Markets: The Marchands Merciers of Eighteenth-Century Paris, London 1996.