Archaeological material can feed into discussions of sacrifice and pre-Christian myth and religion.

By Dr. Christina Fredengren

Associate Professor of History

Stockholm University

By Camilla Löfqvist

Historian

Introduction

Most often, and traditionally, sacrifice is seen as being used in communication with the divine.1 The practice of sacrifice may be a way of relating to the spirits of particular parts of the landscape and works to make selected places more holy. Sacrifice can also, for example, be understood as the process where some human and non-human others are selected, treated elsewise and rendered killable. Hence, this process deals with the management of relations between different bodies, but also with the exercise of power and control of the life/death boundary, where some bodies are given up in order for others to prosper. In this way, sacrifice is a technique that can be enrolled in what is called Necropolitics2 i.e. in the exercise of political, social and religious powers that decides who should be killed and die. Also, Agamben3 writes of how early Roman law regulated sacrifice and killability, and by othering some people, created states of exception.

As Brink has mentioned,4 sacrifice of different kinds is evidenced in written sources such as the Guta Law. Sacrificial practices, or blót, were seemingly discussed as the church in the Middle Ages saw it necessary to ban them. Of particular importance in the Old Norse cognitive landscapes were lakes and springs that from time to time received depositions of artefacts even in Viking times and possibly in the Medieval Period.5 However, the archaeological evidence for human and animal sacrifice has not always been forthcoming in a straightforward way and there is a need to discuss what types of deposition qualify as sacrifices. This paper publishes some of the results of the research project The Water of the Times that has mapped and radiocarbon dated human and animal remains depositions in wet contexts in Sweden. The aim of the project is to understand what effects these depositions had during the Late Bronze and Iron Ages and to investigate what entangled relationships between human, animals, environment and the divine that came into being at different times through these.

The project deals with the following questions:

- where and when the practice was common

- who was considered killable and deposited in different periods

- how they were treated in life and death• what effects these depositions may have had on the transformation of society

The current paper focuses on depositions of human and animal remains in waters and wetlands in the wider Uppland region, where this archaeological material can feed into discussions of sacrifice and pre-Christian myth and religion (and possibly even have a bearing on post-conversion matters as indicated by some late radiocarbon dates). An overview of this material can be found in Fredengren 2015,6 where the general occurrences of skeletal remains depositions and dates were published, thereby dealing mostly with the question of when and where the practice was common. Fredengren and Löfqvist7 provide a case-study of the finds from Torresta in Uppland, where human and animal remains were deposited in the watery environment at a rock-art site during the Bronze Age and Roman Iron Age. The current paper adds a handful of new dates that have come in during the research process and focuses more on presenting evidence necessary for dealing with the questions of who was deposited. It also looks at how these depositions can fine-tune and add to the discussion of sacrifice in Old Norse religion and politics. Particularly, it centres on how such depositions create, change, or maintain particular relations between humans, animals, the wetland environment and possibly also the divine.

Research History

At least since Glob,8 bog bodies have been understood through Tacitus’ writings. They have been interpreted either as slaves that were killed and sacrificed after having attended to the goddess Nerthus, or offenders executed and deposited in bogs after crimes of shame. Hence, the written sources are used both to provide information on their identity as well as reasons why these depositions took place. Furthermore, Tacitus portrays bogs as places away from the public and that this location would make them suitable for receiving the bodies of the disgraced. More recent bog body research often concentrates on the deposited individuals with interesting results.9 Classical bog bodies such as the Grauballe Man come to us as individual icons, both due to the quality of preservation and the way they are analysed and discussed. This current paper deals with skeletal remains from watery places such as lakes, rivers, streams and bogs. It provides a material that includes both human and animal remains from a number of different places in Uppland. Instead of focusing on one individual, the research deals with human and animal collections of bodily remains.

Bog bodies are mainly associated with countries such as Denmark, the Netherlands, Britain and Ireland. Ravn10 has established that 145 out of Denmark’s approximately 560 bog bodies date to the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, where most belong to the Pre-Roman Iron Age. Fabech’s11 reasoning about the use of human, animal and food sacrifices (named fertility sacrifices) in wetlands also underlines that depositions of human remains in wetlands were carried out mainly during the earliest Iron Age. In that paper it is argued that there would have been a shift in religious manifestation between the Pre-Roman Iron Age and the Migration/Merovingian Periods, and seemingly fertility and war-booty sacrifices in wetlands ceased and the cult moved into more formal settings in dryland environments. This in turn was associated with the fall of the more hierarchical, West-Roman society. In Fredengren 201512 and below it is shown that depositions of human and animal remains in wetlands continued well after these time periods in areas such as Uppland. Also, this material suggests that there are rather complex patterns of depo-sitional differences; in species composition, practices for handling the bodies as well as in temporal variation. It might even be so that there are differences between regions.

Overview of the Material

Bog bodies and depositions of skeletons in bogs are known in Denmark,13 Norway14 and Finland.15 However, Sweden has been associated with only a few cases such as Bocksten Man or Dannike Woman. However, well known depositional locations are also Skedemosse and the sites around the country accounted for in Hagberg.16 However, our project has, through surveys of archives and museum stores, been able to locate well over 100 places where human or animal remains have been found in wetlands, with concentrations in Skåne, Västergötland, Uppland, Öland and on Gotland. In Uppland, human and animal remains have been found in 17 water and wetland locations that together represent 117 human and animal individuals.

Not included in these numbers are finds from wells such as Apalle, Kyrsta or Gödåker, that together with the rather uncertain finds from Läby would bring the numbers up to 21 locations (as mentioned in Fredengren 2015). Of these, 55 human and animal individuals have been osteologically analysed by the current pro-ject. The other 62 have for various reasons been unavailable in the museum collections or remain in storage with the firms that excavated them. This group is accounted for in our analysis as paper bodies. There are 21 paper humans (PH) and 41 are paper animals (PA). Examples of these are the finds at River Örsundaån, that is noted in archaeological documentation, but where no corresponding collection can be found in the physical osteological archives in museums. These are bodily remains where there is only a paper record and within this category we have included bodies recorded by heritage institutions such as the Swedish National Heritage Board or the Swedish History Museum. However, some of these paper bodies have been analysed by other osteologists and have therefore added in greater detail to our database. Others have been mentioned in museum or heritage board documentation where on occasion only species is mentioned and where there may be no information on sex, age, pathology or trauma type. Hence, the database consists of records with a somewhat uneven depth of information. This also means that numbers and percentages of, for example, pathologies and trauma may be somewhat uncertain and even underestimated, as a number of paper bodies have no information on these and other traits. The category of paper bodies could also be expanded by records from folklore collections17 – however, that is not carried out in the current research compilation.

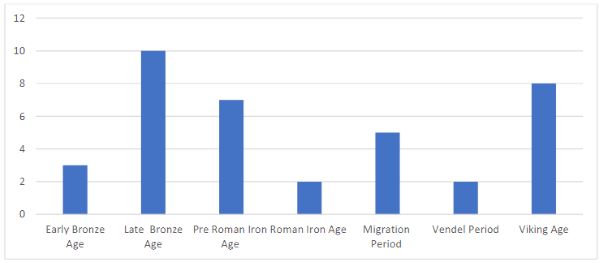

The radiocarbon dates from Uppland stretch from the Bronze to the Viking Age (see Fig. 1). The diagram shows a rise in the numbers during the Late Bronze Age and Pre-Roman Iron Age. Hence, there are similarities with the peak in dates of the Danish material. Also, the number of dates in the Viking Age is rather high. However, this diagram gives a somewhat skewed picture with regards to numbers, as excavated sites such as Riala with more dates get a heavier weight compared to other sites and affect the number of individuals from the Late Bronze Age. There are also a few dates in the Medieval Period as well as modern dates from two sites, Rickebasta and Riala. Also, many of the sites have more skeletal remains than those that were radiocarbon dated; hence, these results may give a biased picture and can change when further dating takes place.

Who

The question of who was selected for deposition in watery places is here approached through osteology and rests on the osteological analysis carried out by Camilla Löfqvist.18 The theoretical background for this discussion is dealt with in Fredengren 2013. The term figuration is used instead of identity in order to pay respect to the fact that the persons discussed consisted of, changed and came about through a variety of relations that cross-cut conceptualized identity borders. Here, the question of who was deposited is qualified by an investigation into what relations were woven together through sacrificial practices. However, such relations are narrowed down and abbreviated when they are captured in archaeological discourse and through the osteological nomenclature.

Having said that, the following section makes use of standard osteological categories while bearing in mind the caveats of fixating the material in this way. It explores selection practices and what life-stories are evidenced in the human and animal remains in order to see whether there are any patterns in their bodily figurations that could explain their killability and deposition in waters away from burial grounds on land. This means to look at the composition of species in the material, at age and sex factors, but also health and life-style indicators. This is followed by a section on their death histories. When possible, the selection and treatment of animals is compared and contrasted to that of humans. In some cases, there is published information on selection processes in other material that is used as contrast material to the remains from Uppland.

Life – Species, Sex and Age

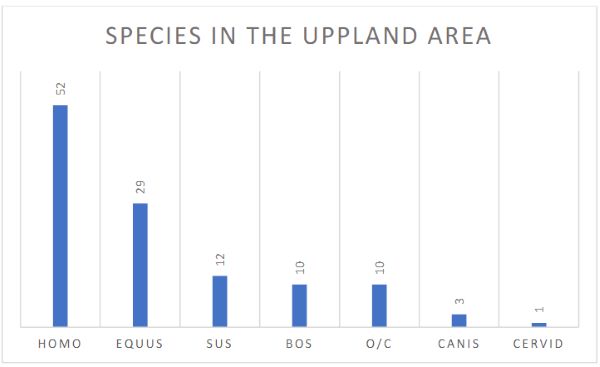

What is remarkable about the Uppland material, in comparison to collections from other parts of Sweden, is that it contains a high degree of human remains depositions from watery contexts. Of the 117 individuals, there are 52 (44%) human and 65 (56%) animals (MNI).

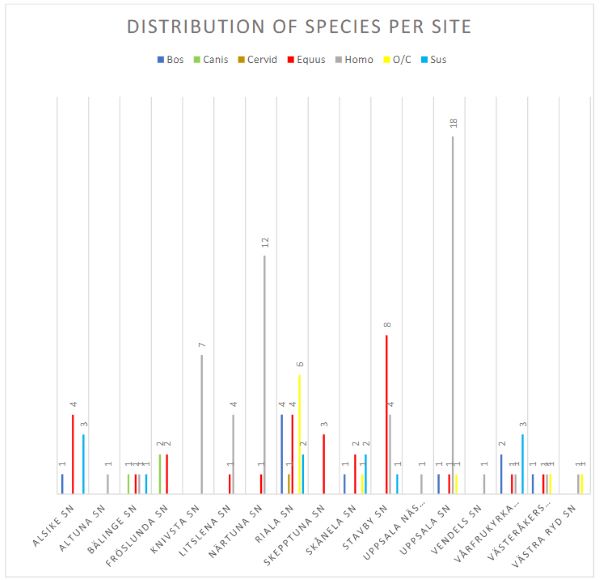

Some locations have more depositions than others. The location by and in the River Fyrisån in Uppsala Parish has yielded 21 human and animal individuals. This is followed by Hederviken in Närtuna Parish with 13 individuals and Lake Bokaren in Stavby Parish with 13 individuals each. The high numbers are due to the fact that they are in well-frequented areas or that they have been formally excavated. Many have both human and animal remains.

The animal remains consist of horses (24%), pigs (10%), cattle and sheep/goat (approx. 8.5% each). Dog and deer have a minor presence in the material.

Horses have often been associated with sacrifice.19 This is further emphasized by the wetland material from Uppland pre-sented here. However, there could be regional patterns in the species composition at sacrificial sites. The species in the Uppland depositions can, for example, be compared with the accumulation of bones at a selection of sites on and around Uppåkra in Skåne as accounted for by Magnell.20 Here, the depositions around ceremonial house and weapon deposition at Uppåkra show an abundance of cattle (with percentages of 64 and 72%, calculated on NISP instead of MNI). In Magnell and Iregren’s study around the island of Frösön,21 located in the northern half of Sweden, other species patterns occurred. A deposition of animal bones beneath the church, considered to be a blót site, contained not only the bear bones that the site is best known for, but where pigs were the most common sacrificial animal, followed by sheep/goat and cattle. As mentioned by Magnell,22 the ordinary relationship between species at a Mid-Swedish Iron Age farm would be a majority presence of cattle, followed by sheep/goat and pig.

While the focus on humans and horses in Uppland may indeed signal regional selection patterns, there might also be temporal differences within the material itself (hence it is a little problematical to group together and compare materials that could have accumulated at particular sites over time). Judging by the radiocarbon dates in Uppland, broadly speaking, it is more common to find animal bone depositions during the Bronze Age and human bone depositions from the Pre-Roman Iron Age and onwards. With more detail on species, it seems that the Bronze Age material mainly consists of cattle, but also pig, sheep/goat and horse are present. Hence, the focus is on domesticate animals that would have been present on farms and that people would have had more day-to-day relationships with. It is worth noting that cattle do not occur after Period 1 of the Pre-Roman Iron Age in these depositions. Instead, there is a marked shift through the periods from the Pre-Roman Iron Age, into the Roman Iron Age and the Migration Period where the variation of species lessens. There seems to be a particular focus on humans and horses, with a rare occurrence of dogs from one site at Fröslunda. Horses can be noted particularly in the Migration to Merovingian Periods. Whilst human remains in depositions increase during the Pre-Roman Iron Age, they more often date to the Merovingian and Viking Periods.

Age Distribution

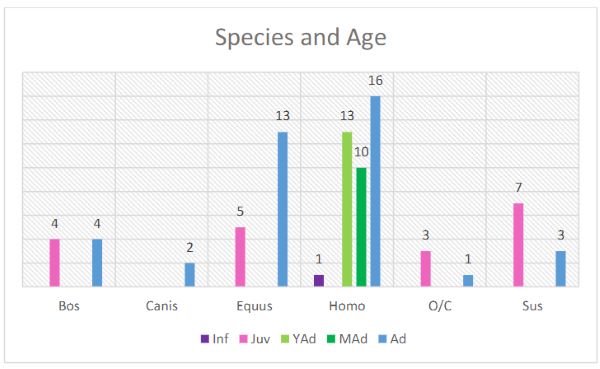

Individual animals are generally determined as either juvenile or adult. Of the 65 animals, 23 were adults and 19 juvenile individuals. Horses were mainly adults, but young animals were also deposited. Both pigs and sheep/goat depositions mainly made use of juvenile individuals. Cattle, on the other hand, show the same percentage of juvenile and adult animals, suggesting equal importance between meat (young animals) and dairy (older animals) producing animals.

The deposited humans are with one exception adults. Out of the 40 aged human individuals, 32.5 % were young adults followed by mature adults (25%). In the human group 40% could be determined as adults only. This is due to the preservation and fragmentation of the bones. One vertebra fragment of an infant was found at Lake Bokaren, Stavby Parish.

The age profile for bodies of humans and animals in the depositions differs somewhat, where juvenile humans seem to have been avoided, but both juvenile and adult animals were eligible for deposition in watery places.

Sex and Age of Humans

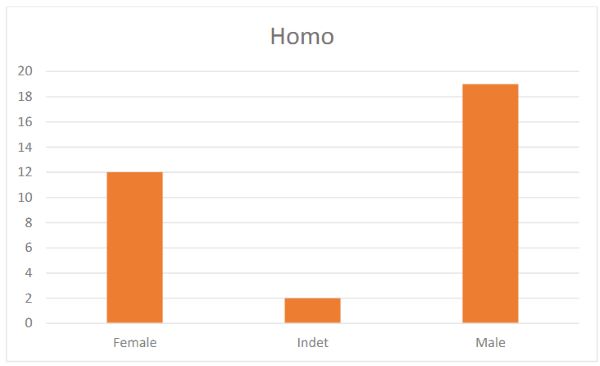

Out of the 33 humans with osteological sex determinations, there were 19 males (57.5%), 12 females (36.5%) and two individuals (6%) of indeterminate sex (Fig. 5).

Some animal remains have skeletal sexual markers; teeth show that two pigs are females and one male, while the pelvis from a sheep/goat indicates a female.

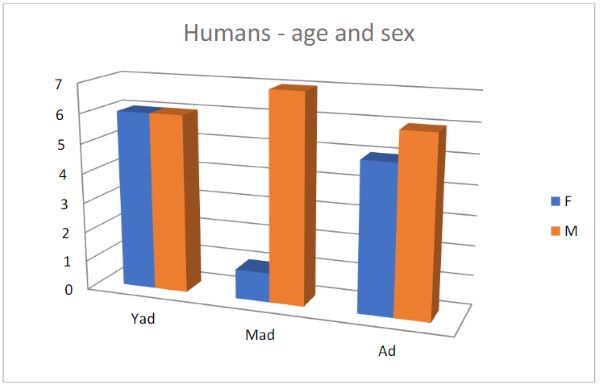

When bringing in the variables of sex and different age groups, a divergence between the males and females becomes obvious. Of the 31 human individuals that could be determined as to both age and sex (Fig. 6), the pattern shows that males are distributed rather evenly between age groups. However, there are mainly young adult females (MNI 6) and only one individual in the mature adult age group. The pattern suggests that its particularly young adult females that were being deposited in these watery places.

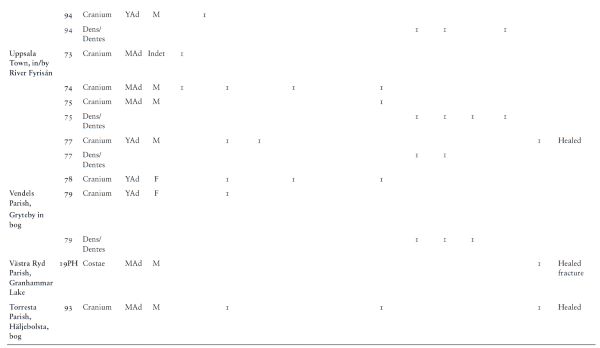

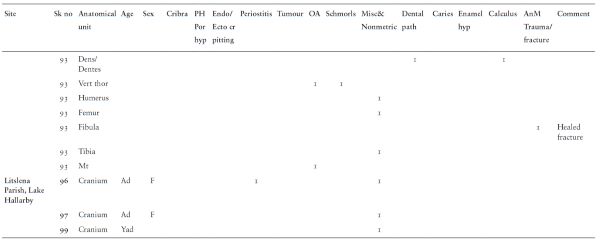

Disease, Malnutrition, and Ante Mortem Trauma

Parts of these persons’ life-styles and relations to others can be detected in the skeleton. For example, bone can carry the imprint of a variety of diseases such as tumours, arthritis, caries, of a deteriorated health condition and/or malnutrition, as can be evidenced in pitting of the skull (cribra, porotic hyperiotis or other cranial pitting) and alterations in the teeth enamel (enamel hypoplasia).

There could also be evidence for bone trauma during life (described as occurring ante-mortem) accrued through accidents or violent relations with others. However, it should be noted that there are a range of diseases and trauma that will not leave any traces on the bone.

Pathologies

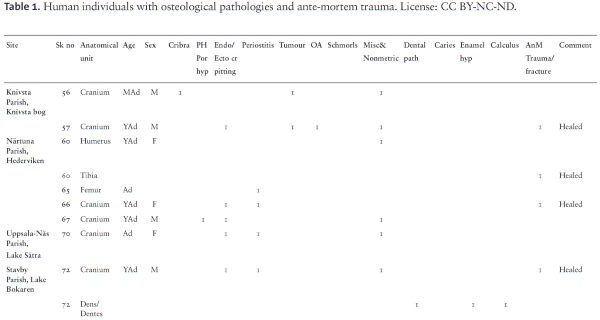

Evidence of pathologies were detected on a total of 20 human individuals out of the total number of 52 (i.e. 38.5%) and one animal (1.5%). In the group of humans with pathologies there were 10 males, 7 females and 3 indeterminate. One animal, an adult horse from Knyllinge, Fröslunda Parish, had pathologies on the shoulder blade resulting from repeated stress or a single traumatic event.

The most common pathology on humans was endo- and ectocranial pitting and periostitis. In the majority of cases these were associated with ante-mortem trauma to the head. This suggest that the ante-mortem trauma to the head might have caused infections, but that the trauma and infection has healed, indicating that the people had some means of treating wounds and injuries. The individuals with such pathologies are, for example, skeleton (Sk) 93, a male from Torresta that dates to the Roman Iron Age. This person displayed multiple pathologies and trauma during their life. The cranial and postcranial remains of this male, aged 35–45 years, for example reveal mild degenerative changes to the spine and joints of the long bones as well as ectocranial pitting on the skull, possibly indicating iron or nutritional deficiencies, but also healed ante-mortem injuries such as a possible fractured fibula. Apart from the mild joint condition in several bone elements, this was also found to be more severe on some of the metatarsals expressed through pitting and deformation of parts of the skull.23

Cranial pitting can be found on both male and female skeletons. However, cranial pitting in combination with trauma were found on Sk 57 from Knivsta, Sk 66 from Hederviken, Sk 72 from Bokaren. These are all males that date to the end of the Viking Period. The last one, Sk 77, a male from the River Fyrisån remains undated.

Six individuals might have suffered malnutrition or disease in early childhood. There are three individuals with enamel hypoplasia. One of these, a female from Gryteby, Sk 79, dates to the Early Bronze Age, while the others belong to the Early and Later Iron Age (Sk 72 Bokaren (as above), Sk 75 a male from the River Fyrisån Rudan). A further three individuals (5,8%) showed traces of cribra orbitalia (Sk 56 a male from Knivsta, Sk 73 of indeterminate sex and Sk 74, a male, both from the River Fyrisån).

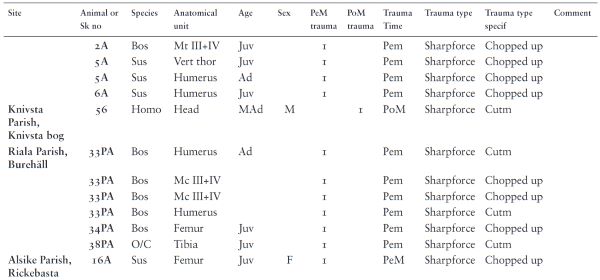

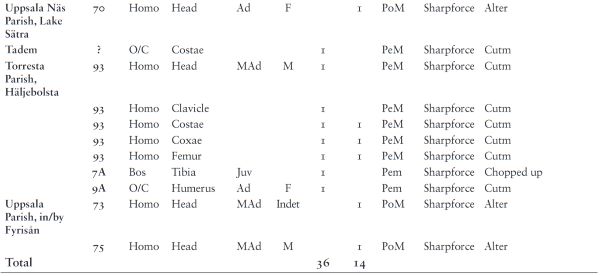

As can be seen in Table 1 all sites with human remains depositions also have individuals with some sort of pathology and/or ante-mortem trauma.

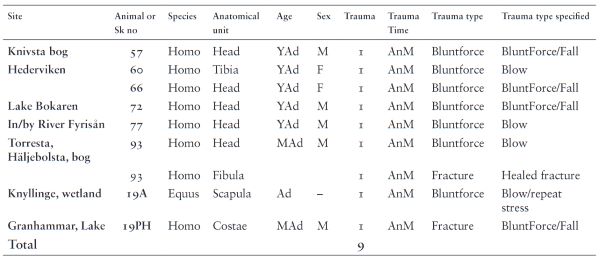

Ante-mortem Trauma Pattern on the Animal and Human Bone

Trauma, such as for example fractures, is together with dental and joint disease regarded as one of the most common pathologies in the archaeological material.24

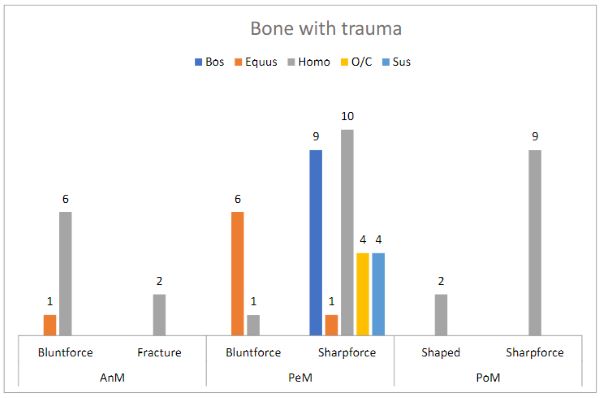

Taken together, evidence for trauma could be found on a total of 55 bone elements divided between 36 individuals, whereof 17 were humans and 19 were animals, and had occurred ante-, peri- and postmortem (Fig. 7). Some individuals displayed several trauma types, for example two human individuals (Sk 72 & 93) who displayed both AnM and PoM trauma while a further one human individual (Sk19PH from Granhammar) had records both of AnM and PeM trauma. Sk 60 and Sk 93 had been exposed to AnM, PeM and PoM trauma. Seven humans (13.5%) and one animal (1.5%) display ante-mortem trauma on a total of 9 bone elements. These are dealt with in the section below, while PeM and PoM are discussed under the following heading.

Looking at the seven human individuals displaying AnM traumas, it can be noticed that blunt force trauma to the head was most frequent. One mature adult male exhibited both a well-healed trauma to the lower fibula as well as a blunt force, now healed, trauma to the head (Sk 93, Torresta). The changes to the fibula are most likely due to a fracture or possibly a sprain. A second mature adult male, from Granhammar, 19PH, had fractured a rib, which was well healed by time of death.

Individuals Sk 57, 66, 72 and 77 had all been exposed to a blunt force trauma to the head which were all healed. The injuries were caused by blows to the head or possibly a fall. Besides Sk 66, a female from Hederviken, these were all males. Also, Sk 60, a female from Hederviken, seems to have received at blow to the lower leg (tibia) which was well healed at the time of her death. The majority were young adults, possibly indicating that they had fought and survived the injuries they received.

As mentioned above, the shoulder blade of a horse showed traces of a well-healed trauma, possibly caused by one single traumatic event or by a repeat stress to the bone. The injury may have caused the horse to go lame. The fact that the injury seems healed suggests that the horse had been cared for and would have been given time to recuperate, indicating that the individual was valued as working animal and/or as a pet.

Death – Killing, Selection of Body parts, Handling, and Deposition

This section follows the death histories evidenced in the material and of particular interest is investigating trauma that could help in the discussion of sacrifice but also throw light on the handling of bodies and the selection of body parts for deposition.

Death can occur due to disease, accidents or drowning that does not necessarily leave traces on the skeleton. The skeletal remains presented here show the injuries that have resulted in imprints on the skeleton. As will be shown, there are both traumas to the bodies that occurred perimortem (PeM) – i.e. associated with the time of death and postmortem (PoM) some time after death and when the bones had lost most of their plasticity. There seems to have been a particular selection of body parts for deposition and some bones were also handled and altered/shaped before their deposition in wetlands.

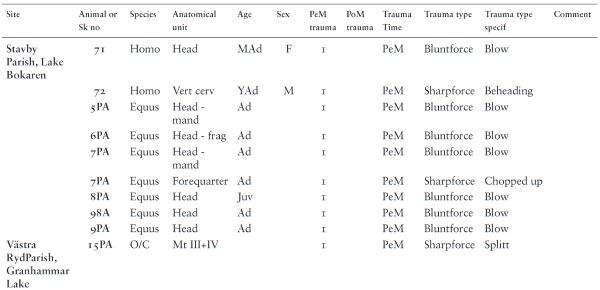

Perimortem Trauma

Out of the 117 individuals in this study, there were a total of 23 human and animal individuals that displayed perimortem trauma, 18 animals (27.7%) and five humans (9.6%).

The material suggests that these have been exposed to a slightly higher degree of trauma when compared to, for example, Medieval Sigtuna where 5.5% (or 2.6% if the mass grave is excluded) of the adult population displayed sharp force trauma. Other sites to compare with are Medieval Lund (0.6%), St. Stefan (7.3%) and Westerhus (2.9%).25

The bone assemblage can crudely be divided into two groups, one where the perimortem trauma indicates killing practices such as a blow to the head or beheading, and another group where the trauma suggests that the bodies were dismembered (mainly animal bone material).

The first group contains both human and animal material. Parts of this group consist of horses from a wetland site at Bokaren in Stavby Parish.26 Six of these were mentioned by Lundholm27 and a further two horses (one juvenile) were discovered during excavations in 2015. Out of these eight individuals, five had been exposed to a blunt force trauma, most likely a killing blow, to the head. One of these individuals also had their front legs cut off at the knees. Furthermore, a vertebra from the tail of this individual suggests the skull, feet and tail, so the inedible parts, had been deposited. It seems likely that these individuals had been killed by a forceful blow to the head whereby the head and possible lower extremities has been deposited at the site.

From Bokaren, there are also remains of four humans, of whom two had most likely received perimortem blows to the head before they were placed in the watery deposit. A mature adult female (Sk 71) from this site had received a PeM blunt force trauma to the head. The location at the forehead, above the left eye, suggest that this blow was dealt by someone facing her. The shape and outline of the depression in the skull suggest that she was hit by something large and heavy, possibly an oblong oval-shaped stone club or something similar. Though the blow was hard, it did not completely penetrate the skull as with the above-mentioned horses. However, it would most likely have stunned and immobilized the individual and, considering the heavy blow, it might have resulted in death. The bone showed no traces of healing.

A second individual from Bokaren, the young adult male (Sk 72) with ante-mortem traumas to the head also had perimortem trauma. A cervical vertebra displayed two parallel cuts which suggest a possible case of cutting of the throat or a beheading (Fig. 9). The third human individual from Bokaren, Sk 94 has no skeletal evidence of trauma.

However, Sk 19PH, a mature adult male from Granhammar, displayed cuts to more than one bone element. Several cuts were detected on the skull but also on the humerus, radius and ulna of the left arm. Perhaps they indicate defensive injuries.

Sk93 from Torresta displayed several perimortem cranial and postcranial injuries caused by sharp force trauma. As there is no sign of healing, it is likely that these injuries were received at around the time of death. Injuries to the skull included several cuts to the back of the head, likely caused by a sharp, probably metal implement, and possibly indicating the intention of decapitating this individual. Further sharp trauma has been recorded on the right clavicle, the ribs, left coxae and both femurs, where cuts were into still soft bone and were likely received around the time of death.28

The second group consist of animals considered to produce, for example, meat, milk etc. such as cattle, sheep/goat and pigs. The bones as well as traumas mainly indicate a deliberate, selective process which, together with the location of the cut marks and the helical fractures to high marrow-bearing elements, suggest these animal individuals were butchered i.e. their bodies were dismembered to become meals. This would fit with the number of piglets and lambs in the depositions. Hence, it is likely that these ani-mals were used for food before their bones were left in the water environment. These animals were from sites such as Granhammar, Hjältängarna, Riala, Rickebasta, Tadem and Torresta. Here, the osteological material provides no particular information on how the animals were killed. Strikingly, there is also evidence that human bodies were divided up at the time of death. The left distal radius of Sk60, a young adult female from Hederviken, showed clear evidence of the bone being cut up. This is suggested first by a possible “false” start followed by a cut through the bone. The edge is very straight and is parallel to the “false” start cut. It is also possible that the proximal diaphysis has been cut. This type of appearance on an animal bone would likely be interpreted as a butchery mark.

Postmortem Trauma

There is evidence that some of the bodies were not deposited in the wet contexts directly upon death, but that they were curated and modified before deposition. Seemingly some of the bodies were exposed to violence after death.

In all 11 human individuals had been exposed to mainly sharp force postmortem trauma. Of these, the majority, a total of nine, had cuts to the skulls. In six of the cases it seems as if the intention has been to shape the skull. This can be seen as straight and clear cuts through part of the skull bone that is very hard and thus would not easily break naturally. A crude bowl-shaped appearance, as well as polished surfaces possibly from being handled might suggest occasional postmortem alterations and shaping of bone. Examples of this are Sk 58, 64 (Fig. 11) and possibly 67 from Hederviken, Sk 56 from Knivsta bog and Sk 70 from Lake Sätra. Such traces were possibly also Sk 99 from Lake Hallarby.

Two individuals (Sk 60 & 61, Hederviken) had cuts to long bones such as the femur and humerus indication the bodies had been dismembered before deposition. One femur (Sk 61, Hederviken) also had traces of possible gnawing, showing that scavengers had access to the bone at some stage. The last individual had perimortem cuts to several bone elements, but also a few cuts to rib, pelvis and femur which possibly might be postmortem.

What these examples show is both that the bodies, in order to have been available for being dismembered or shaped, most likely were killed and decomposed elsewhere than in their wetland depositional locations.

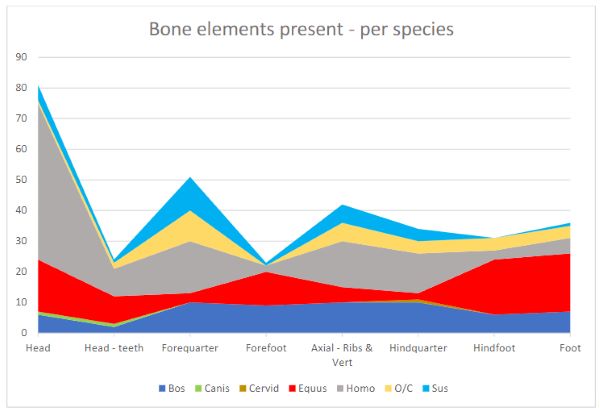

Bone Elements

It is quite rare to find full body depositions in the Uppland material. Instead, it seems that there is further evidence for that there was a selection of body parts that were suitable for deposition. It is worth noting that bones can also become detached from each other due to taphonomic processes and that skulls are easier to identify and retrieve.

Bone elements from all anatomical units were present in the material. On meat-producing animals these can be divided into regions where the meaty parts are considered to be: the spine and ribs, the front quarter (shoulder and front legs) and the hindquarter (pelvis and hind leg). The less meaty regions are the head including the lower jaw, the fore- and hindfoot (metapodials, carpals and tarsals) and the foot (the phalanges). The least meaty region includes teeth, horn core and antler. It has been argued elsewhere that it is mainly the less rich body parts that were deposited in wetlands.29

The material presented here suggests a modification to this view, which seems to be species-dependent. It is clear that sheep/goat and pig follow have a majority of the bone elements from the meat rich areas such as fore- and hindquarter as well as from the spine and ribs. The horse, on the other hand, shows a reverse pattern, with a higher percentage of skull fragments, fore- and hind foot together with feet present and hence confirms this pattern. Cattle showed the most even distribution, but with an inclination toward the less meat-rich elements being present. The low number of bone elements from dog were all from the skull while the few deer bones were all from the hindquarters.

Humans stood out through the high frequency of skulls and skull fragments present adding up to 44% of the human bones analysed (52% including the teeth). Rarer were those individu-als that were represented by their full bodies in the depositions. Here Sk 19PH from Granhammar, Sk 93 Torresta and Bokaren Sk 94 indicate depositions of the corpse directly after death in wet ground.

Depositions in the Bronze Age and Pre-Roman Iron Age

The general traits of this material are that the sites established during the Bronze Age and Pre-Roman Iron Age can be found around the rock-art rich areas of Enköping, but some are also found fur-ther afield. At Hjältängarna the survey inventory describes that this is a wetland area located on both sides of parish boundaries of Härnevi and Vårfrukyrka. While this area is situated to the south of the larger waterways that today form River Örsundaån, the area drains into present-day River Enköpingsån. Here, the inven-tory text mentions how both human and animal remains have been retrieved in the locality from time to time. The site seems to be spread out across a 100 m area, where human, horse, cattle and pig bones have been found. Of these bones, only a small number of cattle and pig bones have been retrieved in museum storage that could be dated by the project. These have overlapping radiocarbon dates in Periods III and IV of the Bronze Age. However, this seems to have been a more extensive depositional site and the presence of human and horse bones may suggest that it was also used in other periods. The depositional area is surrounded by rock-art sites. There are numerous cup-marked boulders, but also some cross-formed pieces.

This site resembles that of Torresta, situated to the north of River Örsundaån.30 Here, animal bones from cattle, horse and sheep/goat were found. These can be dated to the Bronze Age and Periods II, IV and V. There was also a male human skeleton that belongs to the Roman Iron Age. These were retrieved from a wad-ing place across what now is a drain – but what would have been much wetter ground in the past. This wading place is flanked by cup-marked boulders, one on each side of the water. On higher ground there is also rock-art with ship-carvings. Similarly, the con-tract excavations at wetlands in Riala have produced cattle, pig and horse bones that can be dated to the end of the Late Bronze Age and the beginning of the Pre-Roman Iron Age. Rock-art is also present here. Near the depositional spot is a vertical cliff. Here a composition of a cross, surrounded by nine concentric circles faces out over the depositional area. Several cup-markedrocks and a rockslide are located in the vicinity of the site. There are structural similarities between this rock art and the depositions in water. The cutting into the stone can also be understood as a material practice that penetrates beyond the surface, into the inner parts of the rock. The deposition of items in watery places also penetrates the surface and reach into the elements of wet-lands and waters. Both practices can be said to work to perforate two different membranes of the world and stretch into and make physical contact with the underworld.

Approximately 12 km to the east of Hjältängarna is another depositional place with associated rock-art that has human remains that can be dated to the Pre-Roman Iron Age and the Migration Period. Here, at Lake Hallarbysjön other items have also been deposited. An amber bead has been retrieved from the area where the skeletal remains were retrieved. Furthermore, what may be parts of a Late Bronze Age twisted torque was found in this general area during farming. There is a need for further field-work in this location to investigate whether it was a part of a larger hoard of similar items and the connection to the bone-findsby the lake. During the Pre-Roman Iron Age there is evidence for more depositions in mid-Uppland at sites as Lake Sätrasjön, Tadem and possibly also Stora Ullentuna.

Depositions During Roman Iron Age and Later Periods

There are sites with dates that overlap the Bronze and Iron Ages, such as Torresta. Other sites such as Bokaren have the earliest dates in the Roman Iron Age (a period of few depositions). During the Migration Period, sites that were used for depositions in ear-lier periods seem to have been re-activated by the deposition of the remains particularly of horses. This is exemplified by the finds from Lake Hallarbysjön, Tadem, Bokaren and Rickebasta.

It is worth noting that Rickebasta is situated next to Tuna in Alsike, which would be considered as a centre at least on the borders between the Migration and Merovingian Periods. Other site such as Hederviken and Knivsta seem to have been used mainly during the Viking Age, where the depositions in the River Fyrisån uphold a middle position. The role of these sites in the politics of Iron Age Uppland has been dealt with elsewhere.31

Discussion

Sacrifice is a particular way of dealing with the end of life. It can, for example, be understood as a management of human and animal finitude, sometimes used for communication with the divine, but also as a way of transforming inter-species relationships as well as the relationships between humans. Furthermore, sacrifice can be used to alter the relationship with the divine and the landscape.

This paper publishes some of the results of the research project The Water of the Times and traces what bodies were used for depositions and sacrifices and how they, with all their network connections, can be understood as sacrificial figurations. The content of the depositions indicates shifting species relations with regard to which bodies were rendered as killable in order to be sacrificed and possible to deposit in wetland places in Uppland. As mentioned earlier, during the Bronze and earliest Iron Ages the depositions mainly contained domesticated animals such as cattle, sheep/goat, pig and horses. Most likely, people would have had quite close relationships with and tended these domesticated animals on a next day-to-day basis. There is not much indication of the welfare of these animals in these skeletal remains. Besides the trauma to the shoulder of the horse from Knyllinge, there is no clear evidence in this material that violence was inflicted on these animals when they were still alive or if they were treated with care during their life. However, more studies are needed that pay attention to issues of animal welfare in the past.

The content of the depositions shifted considerably over the Iron Age when humans and horses dominate the material. This suggests that the relationship to these animals as well as that towards humans seems to have altered considerably over time. The human bone material presented here has supplied a number of cases where both the life and death histories of the individuals have been rather troubled. One example is the person from Torresta who was exposed to violence both during life and death. There seems to be evidence for a path-dependency in this, but also in other cases for that a violent and neglected life also ended in a traumatized way, as if the sacrifice played a role in other politics of exclusion. What is particularly striking is the number of individuals with challenged health status that were deposited in the Viking Age and the fact that many males also were exposed to violence during their lives. Hence, these depositions can be read as examples of changing relationships in the practice of Necropolitics, where those in focus for these altered over time in the Uppland area, where some deaths were managed and possibly became a part of public display and later deposition in wetlands.

Throughout this paper the term depositions in wetlands has been favoured over the term sacrifice and as flagged for at the beginning there is a need to discuss what is actually counted as sacrifice. At a broad level, all depositions in wetlands can be understood as sacrifices, but the issue is more complex than this. As shown above, there are indeed cases in this material that qualify for a narrower archaeological definition of sacrifice, where there is evidence of lethal perimortal violence, with no evidence for defensive injuries on the skeleton and where the deposition was carried out in a particular selected part of the archaeological landscape. One example of this is Torresta, where human remains were deposited in a wetland location at a fording place that had been marked by rock-art. What is more, earlier animal remains depositions were retrieved from this place, which attests to a placing of the bones at a traditional depositional location. At the same time, the skeletal evidence points to a life history of neglect. Another example is the site of Bokaren with a depositional tradition that stretch over a span of some 1,000 years and where there are both human and animal remains with evidence of perimortal, lethal violence.

When it comes to how the dead bodies were handled, there are only a few examples of full bodies having been retrieved from the wetlands. On many occasions, however, only certain body parts were deposited (sites like Bokaren have received both full bodies and body parts). Seemingly, in these cases when only body parts are present, both the actual killing as well as the decomposition and handling of the bodies must have taken place away from the wet areas. There are examples of when the more meat-rich parts of bodies were deposited – hence, such depositions can possibly be interpreted as providing food for the divine. There are other examples of depositions of less meat-rich parts being used in the depositions and where possibly the meat-rich parts were used as food for the living, who possibly shared the meals with the divine or the spirits. Adding to the variation in practice is the evidence that points to the fact that certain bodies, after their death and decomposition, must have been curated, handled and carved into before being deposited at a particular wetland location. However, these may also under certain circumstances be understood as sacrifices as they could have been a part of a practice centred on the giving up of some bodies or body parts in exchange for something else to prosper.

Traditionally, sacrifice is understood as a way of communicating and carrying out an exchange with the divine or with spirits of various locations in the environment. Besides that, sacrifice may be connected to a wish for good crops, for status or for a society to prosper, and these practices may also indicate particular types of relationships with the landscape. As focused on in this paper, the depositions have been retrieved in watery environments and may, as shown in the material above, have worked to weave together the faith of humans, animals and these parts of the landscape, albeit in constellations that changed over time. These depositions form a part of a multi-species history, that may have worked to alter the relationship with the environment. As discussed elsewhere,32 depositions in water may have been understood to work not only to fulfil wishes – but also to draw out sacred power and holiness onto particular places in the landscape. In this way the landscape may have been understood as if it were perforated where the deposition of sacrifices of different kinds would work to channel holy water from the underworld and attract it into the world of the living, thereby making the sacred immanent in the world.

Depositions in wetlands, understood as sacrifices or not, may have worked to indicate, activate and set up a variety of inter-species, age-related and landscape relationships that changed over time. What has been accounted for here is a rather complex material that indicates a variety of inter-species relations, value scales and practices that need to be kept in mind when discussing issues around sacrifice.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Hubert & Mauss 1964 (1891).

- See also Mbembe 2003.

- Agamben 1998.

- Brink 2013:40–41.

- See Lund 2010; Zachrisson 1998; Fredengren 2015.

- Fredengren 2015.

- Fredengren & Löfqvist 2015.

- Glob 2004 (1969):153, 159–163.

- Cf. Asingh 2009.

- Ravn 2010:113.

- Fabech 1991:284.

- Fredengren 2015.

- See Ravn 2010.

- Henriksen & Sylvester 2005.

- Wessman 2009.

- Hagberg 1967.

- See Kama 2015.

- See appendix for catalogue and method.

- Nilsson 2009; Monikander 2010.

- Magnell 2011.

- Magnell & Iregren 2010.

- Magnell & Iregren 2010:233.

- Fredengren & Löfqvist 2015.

- Roberts & Manchester 1999:65.

- Kjellström 2005:82, tab. 5.4.

- See Fredengren 2015; Eklund & Hennius (forthcoming).

- Lundholm 1947.

- Fredengren & Löfquist 2015.

- Hagberg 1967.

- See Fredengren 2015.

- Fredengren 2015.

- Fredengren 2016.

Bibliography

- Asingh, P. 2009. Grauballe Man. Portrait of a Bog Body. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

- Brink, S. 2013. Myth and Ritual in Pre-Christian Scandinavian Landscape. In S. Walaker, & S. Brink (eds.). Sacred Sites and Holy Places. Brepols: Turnhout, 33–52.

- Eklund, S. & Hennius, A. Våtmarksoffer i Bokaren. Avrapportering av gamla undersökningar. Rasbo 137:1, Rasbo socken, Uppsala kommun, Uppland, Uppsala län. SAU rapport 2014:20. Uppsala: SAU.

- Fabech, C. 1991. Samfundsorganisation, religiøse ceremonier og regional variation. In C. Fabech & J. Ringtved (eds.). Samfundsor-ganisation og regional variation. Norden i romersk jernalder og folkevandringstid. Aarhus: Aarhus universitetsforlag.

- Fredengren, C. 2013. Posthumanism, the Transcorporeal and Biomolecular Archaeology. In Current Swedish Archaeology 21, 53–71.

- Fredengren, C. 2015. Water Politics. Wetland Deposition of Human and Animal Remains in Uppland, Sweden. In Fornvännen, Journal of Swedish Antiquarian Research 11, 161–183.

- Fredengren, C. & Löfqvist, C. 2015. Food for Thor. The Deposition of Human and Animal Remains in a Swedish Wetland Area. In Journal of Wetland Archaeology 15.

- Fredengren, C. 2016. Unexpected Encounters with Deep Time Enchantment. Bog Bodies, Crannogs and ‘Otherwordly’ Sites. The Materializing Powers of Disjunctures in Time. In World Archaeology 48:4.

- Glob, P. V. 2004 (1969). The Bog People. London: Faber and Faber.

- Green, M. 1998. Humans as Ritual Victims in the Later Prehistory of Western Europe. In Oxford Journal of Archaeology 17(2), 169–189.

- Hagberg, U. E. 1967. The Archaeology of Skedemosse II. Stockholm: Vitterhetsakademin.

- Henriksen, M. M. & Sylvester, M. 2005. Boat and Human Remains from Bogs in Central Norway. In Archaeology from the Wetlands. Recent Perspectives Proceedings of the 11th Annual WARP conference, 343–347.

- Hubert, H. & Mauss, M. 1964 (1891). Sacrifice. Its Nature and Function. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Midway reprint 1981.

- Kjellström, A. 2005. The Urban Farmer. Osteoarchaeological Analysis of Skeletons from Medieval Sigtuna Interpreted in a Socioeconomic Perspective. Theses and Papers in Osteoarchaeology No 2. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Liebe-Harkort, C. 2010. Oral Disease and Health Patterns. Dental and Cranial Paleopathology of the Early Iron Age Population at Smörkullen in Alvastra, Sweden. Theses and Papers in Osteoarchaeology No 6. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Lindström. J. 2009. Bronsåldersmordet. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Lund, J. 2010. At the Water’s Edge. In M. Carver et al. (eds.). Signals of Belief in Early England. Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Lundholm, B. 1947. Abstammung und Domestikation des Hauspferdes. Zoologiska Bidrag från Uppsala 27. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Magnell, O. & Iregren, E. 2010. Veistu hvé blóta skal? The Old Norse Blót in the Light of Osteological Remains from Frösö Church, Jämtland, Sweden. In Current Swedish Archaeology 18, 223–250.

- Magnell, O. 2011. Sacred Cows or Old Beasts? A Taphonomic Approach to Studying Ritual Killing with an Example from Iron Age Uppåkra, Sweden. In: The Ritual Killing and Burial of Animals. European Perspectives. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 192–204.

- Mbembe, A. 2003. Necropolitics. In Public Culture 15(1), 11–40.

- Monikander, A. 2010. Våld och vatten. Våtmarkskult vid Skedemosse under järnåldern. Stockholm Studies in Archaeology 52. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Nilsson, L. 2009. Häst och hund i fruktbarhetskult och blot. In A. Carlie (ed.). Järnålderns rituella platser. Halmstad: Kulturmiljö Halland, 81–99.

- Ravn, M. 2010. Burials in Bogs. Bronze and Early Iron Age Bog Bodies from Denmark. In Acta Archaeologica 81, 112–123.

- Roberts, C. & Manchester, K. 1999. The Archaeology of Disease. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Wessman, A. 2009. Levänluhta – A Place of Punishment, Sacrifice or Just a Common Cemetery? In Fennoscandia Archaeologica 26.

- Sundqvist, O. 2004. Uppsala och Asgård. Makt, offer och kosmos i forntida Skandinavien. In A. Andrén et al. (eds.). Ordning mot kaos – studier av nordisk förkristen kosmologi. Vägar till Midgård 4. Lund: Nordic Academic Press.

- Zachrisson, T. 1998. Gård, gräns, gravfält. Stockholm Studies in Archaeology 16. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

Contribution (225-262) from Myth, Materiality, and Lived Religion: In Merovingian and Viking Scandinavia, edited by Klas Wikström af Edholm, Peter Jackson Rova, Andreas Nordberg, Olof Sundqvist, and Torun Zachrisson (2019, Stockholm University Press), published by OAPEN under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.