The establishment had been sufficiently frightened to back a right-wing backlash.

By Donny Gluckstein

British Historian

Edinburgh College

Introduction

The co-existence of imperialist war and people’s war in Western Europe during the Second World War was closely linked to the outcome of the First, which saw a monumental struggle between the established powers of Britain, France and Russia, against an ambitious newcomer – Germany. That clash of the rich and powerful caused enormous suffering to ordinary people, so that when proletarians and peasants seized the property of Russia’s capitalists and landowners in 1917 it inspired a wave of international revolution. Although working class power was not secured in any other country than Russia, the establishment had been sufficiently frightened to back a right-wing backlash.

In Germany and Italy, where frustrated imperial ambitions and post-war class struggles were particularly concentrated, rabid counter-revolutionary movements came to power. Hitler and Mussolini had a dual goal: to build new empires at the expense of the old ones, and smash working class organisation. Thus in Western Europe the Axis offensive signified both a renewed bid for hegemony and a naked assault on labour. Twin threats inspired a twin response: inter-imperialist war and people’s anti-fascist war.

France: Imperial Glory versus Resistance Ideology

Germany’s stunning defeat of France in 1940 was one of the most dramatic events of the twentieth century. A mighty European power was humbled in just six weeks of Blitzkrieg. Much criticism has been made of the conservative mindset of French generals who thought in terms of the First World War trenches rather than the latest technology. Hitler’s forces relied on planes and armoured columns that overcame these obstacles with terrifying ease. However, the rout cannot be understood simply in military terms. After all, the opposing forces were evenly matched: Germany fielded 114 divisions and 2,800 tanks; France 104 divisions and 3,000 tanks.1

France’s fate was also influenced by a history of class war at home. On 6 February 1934 extreme right-wing groups attempted to storm the French Parliament but were blocked by police. In the melée 15 died and 1,400 were wounded.2 Although the riot failed to reach its target it brought down Prime Minister Daladier. A united left demonstration of protest followed. The movement became unstoppable and a general strike of 4.5 million showed the determination of the working class to resist fascism.3 This was but the prelude to still larger walkouts. In June 1936 alone there were 12,142 separate strikes. One participant described his feelings:

‘Going on strike is joy itself. A pure joy, without any qualification … The joy of standing before the boss with your head held high … of walking among the silent machines with the rhythm of human life re-established.’4

The same year a Popular Front government was elected.

The close linkage of anti-fascism, workers’ struggle and communism led significant elements of the establishment to conclude that the threat to French state sovereignty from Hitler was the lesser of two evils. De Gaulle, France’s future leader, described the phenomenon in this way:

‘some circles were more inclined to see Stalin as the enemy than Hitler. They were much more concerned with the means of striking at Russia … than with how to cope with the Reich.’5

This explains France’s hesitancy during the first days of the Second World War. Despite formal declarations of belligerency over Poland in September 1939, both Britain (which had reluctantly given up appeasement only just before) and France fought a ‘drôle de guerre’ (phoney war). This involved fairly nominal military action against Germany. There was no such timidity when it came to opposing Russia’s attack on faraway Finland. General Gamelin’s plan to send forces was only thwarted when the Finns sued for peace in early 1940.6

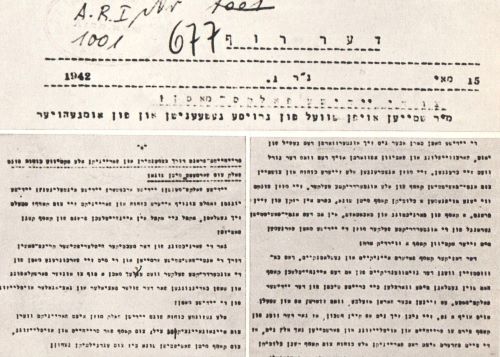

Meanwhile the French government witch-hunted the Communist Party (Parti Communiste Français – PCF). On the eve of the Nazi invasion 300 Communist municipal councils with 2,778 councillors were suspended. Following 11,000 police raids the mass circulation L’Humanité and Ce Soir newspapers were banned along with 159 other communist publications.7 For the first time, elected representatives of the Third Republic were expelled and jailed, and seven communist leaders were condemned to death.8 Employers used this climate of intimidation to victimise the activists and strikers of 1936.9

It was against this background that Germany attacked in the summer of 1940. Its tactics were frighteningly effective, but more importantly, the French government was in a predicament aptly summarised by a refugee from the fighting:

the ruling class in any democratic country … has to rely on the forces of the whole nation, it has to call upon all classes, it has to appeal above all to the working class. Or else it may try to come to terms with the threatening aggressor, appease him, strike a bargain with him – so as to avoid any shock to the social structure ….10

France’s leaders were conscious of the choice. General Weygand, Commander-in-Chief, told de Gaulle of his fear that the country’s military organisation ‘might collapse suddenly and give a free run to anarchy and revolution’.11 He was ready to capitulate, but one nagging doubt remained:

‘Ah! If only I were sure the Germans would leave me the forces necessary for maintaining order!’12

Finally putting this behind him, Weygand stampeded his colleagues into surrendering by claiming that Maurice Thorez, the PCF leader, had begun the revolution and seized the presidential palace – a pure invention!13

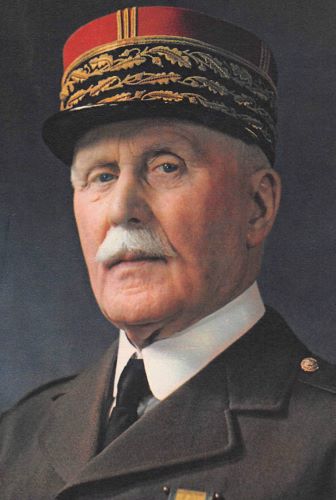

In the midst of this turmoil Marshal Pétain exhibited a sure sense of French history. Ever since the 1789 revolution governments had had to decide between mass mobilisation to repel foreign threats, or suppressing the population to maintain class rule. In 1871, when the radical Paris Commune refused to compromise with German invaders, Thiers had worked with the latter to drown the Parisian working class in blood. Seven decades later Pétain argued that faced with Hitler: ‘the only thing was to end, negotiate, and, if the case arose, crush the Commune [i.e. popular resistance], just as, in the same circumstances, Thiers had already done.’14

In an attempt to instil some backbone Churchill proposed a Franco-British Union with joint citizenship for all.15 The French Cabinet reacted with comments such as:

‘Better be a Nazi province. At least we know what that means.’16

This wish was fulfilled. On 22 June 1940 an armistice with Germany was signed giving the Nazis a northern zone (covering about 55 per cent of the country) under their direct control. Pétain’s collaborationist Vichy regime ran the South.

Among the working class a different view had been evident since the demonstrations of 1934 and strikes of 1936. When the British and French governments appeased Hitler over Czechoslovakia this drew a storm of cheers from the Centre and Right in France’s parliament. The PCF leader countered:

‘France had yielded to blackmail, betrayed an ally, opened the way to German domination, and perhaps irretrievably jeopardized her own interests.’17

Five hundred and thirty five deputies backed the government position, while 75 (of which 73 were communist) voted against.

However, the left was thrown into disarray by the Hitler-Stalin Pact. While Russia and Germany savaged Poland, the PCF leadership called for peace with Hitler. When this came and Nazi jackboots echoed through the streets of Paris, the PCF wrote:

French imperialism has undergone its greatest defeat in History. The enemy, which in any imperialist war is to be found at home, is overthrown. The working class in France and the rest of the world must see this event as a victory and understand that it now faces one enemy less. It is important that everything is done to ensure that the fall of French imperialism is definitive.

There was a qualification added to this amazing statement:

A question to consider is whether it follows that the struggle of the French people has the same objective as the struggle of German imperialism against French imperialism. That is true only in the sense that German imperialism is a temporary ally.18

Not all communists accepted this nonsense. One third of the PCF’s MPs rejected the idea that France was now occupied by ‘a temporary ally’.19

In one respect the PCF was correct. French imperialism had been defeated by German imperialism, though its demise was not ‘definitive’. On 18 June, Charles de Gaulle, a young French brigadier-general who had escaped to London, announced the existence of ‘Free France’ on the BBC:

‘Whatever happens, the fire of the French resistance shines and flames.’20

De Gaulle’s idea of what this resistance would consist of was rather strange. He appealed to the French Commander in Chief of North Africa, the High Commissioner of Syria/Lebanon, and the Governor General of French Indochina to form a ‘Council for the Defence of the Empire’.21 A week later he said ‘powerful forces of resistance can be felt in the French Empire’. On 3 August de Gaulle reported:

‘at numerous points in the Empire courageous men are standing up and are resolved to preserve France’s colonies.’22

It is no surprise that Commanders in Chief, High Commissioners and Governor Generals did not rush to respond, and de Gaulle was forced to re-think how he might save French imperialism. He added two new components to his strategy. Firstly, the Nazis must be expelled and there was no alternative to mobilising the masses, but they must be kept from going too far. He did not abandon his initial defence of empire. Here is de Gaulle’s own formulation:

There would be the power of the enemy, which could be broken only by a long process … There would be, on the part of those whose aim was subversion, the determination to side-track the national resistance in the direction of revolutionary chaos … There would be, finally, the tendency of the great powers to take advantage of our weakness in order to push their interests at the expense of France.23

De Gaulle elaborated on the last point when he called on France’s colonial administrators to ‘defend her possessions directly against the enemy [and] deflect England – and perhaps one day America – from the temptation to make sure of them on their own account’.24

Though the brigadier-general would become its figurehead, in France the resistance developed independently. It began as a ‘chain of solidarity’ – escape routes for prisoners fleeing the occupier. Then ‘networks’ appeared to pass on information to the Allies. Movements organised around clandestine newspapers soon followed.25

In 1941, after Hitler’s attack on Russia, the PCF joined the struggle and the level of direct action and sabotage rose dramatically. In one three month period, for example, the communists alone claimed to have mounted 1,500 actions – 158 de-railings; 180 locomotives and 1,200 wagonloads of materials or troops destroyed; 110 train engines and 3 bridges sabotaged; 800 German soldiers killed or wounded.26 In 1942 an attempt to draft French labour for Germany drove many young men into joining the maquis guerrilla bands. Finally, in 1944 the resistance mounted important diversionary actions to assist the D-Day Normandy landing. This level of action required courage. Resisters were hunted by the Gestapo in the North, and Vichy’s vicious Milice in the South. Torture, the concentration camp, or execution, were real possibilities: 60,000 PCF members were killed.27

The resistance functioned both ‘as a movement’ and ‘as an organisation’.28 As a movement it had a huge following. The daily circulation of its press was 600,000 in 1944, even though possession of a clandestine newspaper could mean arrest by the Gestapo.29 Organised resisters were fewer, amounting to no more than 2 percent of the adult population.30

Who were these individuals who, as an influential northern paper put it, were ‘totally uncompromised, people who have proved their worth under the German occupation’?31 Although the French resistance has been thoroughly studied, the question is difficult to answer because no-one carried membership cards. The evidence there is appears to be contradictory. Regarding social composition, Georges Bidault, president of the National Resistance Council (CNR), wrote:

The Resistance included all types, all classes, all parties. There were workers side by side with peasants, teachers, journalists, civil servants, aristocrats, priests, and many more. For the most part they joined after making an individual choice born from their conscience in revolt.32

This diversity seems to challenge the assertion that there was an imperialist war pursued by the ruling class, and a people’s war backed by the masses. That conclusion is incorrect, however.

The composition of the resistance was heterogeneous because the fight for national independence, and the betrayal of it by the ruling class, enraged many sections of the population. The national struggle and the class struggle overlapped. But, the social composition and the social outlook of the resistance were not identical.

However wide its membership, it was markedly left-wing in outlook, because the French establishment was thoroughly ‘compromised by their solid public adherence to Vichy, and consequently German domination.’33 Isolated resisters bore right-wing, even extreme right-wing ideas, but fighting fascism came more naturally to left-wing circles:34

because it was a matter of pursuing a battle in which they were already engaged … Those who had voted for the Popular Front in France and wished for a Republican victory in Spain were immediately hostile not only to Hitler’s Europe, but also Pétain’s France.35

The PCF component would be expected to use radical language, but it was not alone. The rest of the resistance produced documents that, as one historian puts it, ‘are virtually unanimous in predicting and declaring revolution’.36 Time and again the radicalising effect of occupation and capitulation was illustrated by resistance publications. One article entitled ‘This War is Revolutionary’ explained that it was ‘a fight between two conceptions of the world … authority and liberty’.37 It went on: ‘the masses will not act unless they know what the aim is, and it needs to be an ideal that will justify their efforts and great enough to encourage supreme sacrifice … THE LIBERATION OF HUMANITY’.38 This involved much further than expelling the Nazis:

- Liberation from material servitude: hunger, squalor, the machine

- Liberation from economic servitude: the unfair distribution of wealth, crisis and unemployment

- Liberation from social servitude: money, prejudice, religious intolerance

- And the selfishness of the possessors …39

Libération, the paper of d’Astier, an ex-army aristocrat linked to trade union and socialist circles, took a similar position:

We will fight and struggle, with weapons in our hands for liberation from both internal and external enemies war and national imperialism, the power of money and economic imperialism dictatorship of any sort, whether state, social or religious.40

Such sentiments could not have been more distant from de Gaulle whose instincts were authoritarian through and through. His self-proclaimed motto was:

‘Deliberation is the work of many men. Action, of one alone.’41

However, he understood the need to blend radical language into his defence of French imperialism if he was to have any hope of controlling the movement. So he peppered speeches with phrases like this:

‘In uniting for victory [the French people] unite for a revolution … For us the ending of the war will mean not only the complete restoration of our national territory and its Empire, but the complete sovereignty of the people.’42

But his words lacked conviction and a power struggle developed between de Gaulle in exile and the resistance in France.

Until his death at the hands of the Gestapo in 1943, de Gaulle’s emissary was Jean Moulin. He commanded respect because, when Prefect of the Department of Eure-et-Loire at the outbreak of war, the Nazis locked him in a room with the mutilated torso of a woman and tortured him to sign a document blaming black French soldiers. Fearing he might succumb to pressure he attempted suicide.43 De Gaulle wanted Moulin to ensure the resistance would work for the interests of imperial France rather than the people. His instructions were to:

‘To reinstate France as a belligerent, to prevent her subversion ….’44

The first step was to gain control. Moulin’s orders were to bring the numerous groups of resisters under ‘a single central authority’,45 without which they might ‘slip into the anarchy of the “great companies” or … Communist ascendancy’.46 He first amalgamated southern non-communist groups into the United Resistance Movement (MUR). In May 1943 he formed the National Resistance Council (CNR), which included the communists.

Moulin’s second task was to secure de Gaulle’s political authority in the military sphere, by excluding ideological debate and discussion: ‘the separation of the movement’s political and military activities must result in an autonomous military organisation linked to London from whence it would receive and execute orders.’47 This would be the hierarchical ‘Secret Army’ with which de Gaulle hoped to neutralise the effectiveness of radical elements.

The resistance accepted a more unified structure in the interests of co-ordinated action, but bitterly opposed the separation of military and political functions. Frenay of the MUR insisted that: ‘The Secret Army is an integral part of the United Movement because the latter created all its parts, determined its structure, its orientation, shaped its cadres and recruited its troops.’48 Frenay’s vision of warfare was sharply different to de Gaulle’s:

With us, discipline is achieved through trust and friendship. There is no sense of subordination in the military sense of the term. It is not possible – and we have ample experience of this – to impose officers at any level of our hierarchy. What can be done in a regiment or government office cannot be achieved here.49

Different armies use different techniques, as another resistance leader explained:

On the one hand there were those, usually former officers, who saw it as a point of honour to turn out ‘their boys’ … in a classic conventional army … Others were conscious of participating in a revolutionary war, and for some of them, a veritable international civil war … and in the area of tactics employed exclusively guerrilla methods.50

Neither side won the debate outright and separate militias persisted, ranging from the de Gaulle’s Secret Army, to the PCF-led ‘Franc-Tireurs et Partisans’ (FTP). Others like the MUR sat in between. Each adopted a different strategy. The Secret Army was to serve as de Gaulle’s tool and adopted a classic attentist approach. It waited for the brigadier-general to cross the Channel on D-Day (‘Jour J’ in French).51 This ran so counter to the spirit of the resistance that Moulin was forced to deny rumours ‘that the intention was to forbid any action by Secret Army militants while they waited for Jour J … which is something that is practically impossible anyway’.52

The communist-led movements ignored this wait-and-see attitude and launched high profile actions, often at extremely high cost to themselves.53 They might well have achieved the ‘ascendancy’ that de Gaulle feared (and which was obtained in places like Yugoslavia and Greece) had not the US-led invasion of North Africa (Operation Torch) supervened in November 1943.

Torch went smoothly because in Algiers pro-Gaullist officers, in combination with a resistance movement led by the Jewish Aboulker brothers, arrested the top Vichy officials as well as seizing barracks and command posts.54 No sooner had the Americans landed than they began talks with one of the prisoners, Admiral Darlan. This was an extraordinarily insensitive decision. Even Funk, a semi-apologist for the US’s action, has to admit:

As the chief architect of Pétain’s policy, Darlan [had] exerted his utmost skill to convince the Axis of France’s willingness to cooperate with the Nazi New Order… he pursued exactly the same policies for which Laval, Pétain and other Vichyites were later indicted and for which Laval was hanged. To the French resister Darlan became the epitome of collaboration and surrender.55

Furthermore, Darlan was the anointed heir of Pétain, yet the US freed him and returned the government of North Africa to his hands! Privately Morgenthau, US Secretary of the Treasury, grumbled, if ‘we are going to sit back and favor these Fascists … what’s the use of fighting just to put that kind of people back in power?’56

The resistance movement was stunned, though this outcome could have been predicted. Roosevelt had maintained close relations with Vichy from the start by signing a trade agreement in 1941.57 The US enthronement of Darlan infuriated the French resistance:

‘In no case will we agree to consider the about-face of those responsible for our political and military betrayal an excuse for their past crimes … .’58

Revenge came when the Admiral was assassinated by a resistance fighter.59 The US now turned to General Giraud, who at least had not courted Nazis and was respected for a spectacular escape from their prison. However, according to Funk, ‘Giraud’s attitude – toward Pétain, toward Vichy, toward democracy, toward anti-Semitism – did not differ distinguishably from Darlan’s’.60 A charitable interpretation of Roosevelt’s actions would be that he hoped to prise Vichy away from Germany. More likely, the US wanted its own clients in place as an alternative to the British protégé de Gaulle. Certainly, Roosevelt refused any dealings with ‘dissident groups which set themselves up as Governments’,61 which was code for de Gaulle. Clearly, the US would take anyone who would do their bidding, rather than see a restored a rival imperialism in France.

Operation Torch did not bring about the Atlantic Charter’s promise of ‘the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live’. Under Giraud seven million Algerians continued under the yoke of US-backed French colonialism and its 600,000 French settlers.62 Vichy’s anti-Semitic laws remained intact, as did concentration camps containing elected communist deputies. They were now joined by Gaullists, and the very resistance fighters who had assisted the Allied landing.63

In mainland France the Nazis responded to Operation Torch by brushing aside the Vichy fig leaf and took control of the entire country.64 As the same time the shock of the Darlan incident rallied all the resistance groups to de Gaulle. This gave him a powerful enough base to marginalise Giraud and establish a provisional French government in North Africa. The legitimacy conferred by the newly-formed CNR proved crucial in making de Gaulle the national figurehead. But once his hegemony was secure he completely ignored his followers. Moulin was killed by the Gestapo and his replacement, Bidault, recounts that he wrote ‘hundreds of coded telegrams to the French government in exile … I did get one answer and only one: the only reply that ever reached me was “Reduce traffic”.’65

De Gaulle eventually deigned to communicate with ‘his’ resistance movement at the time of the Normandy landings in summer 1944. General Eisenhower wanted maximum disruption of the Wehrmacht from within France. At great personal cost all the resistance movements threw themselves into battle. In unequal combat thousands died at places like Vercors. Yet still more joined the fray so that the ‘interior forces’ rose from 140,000 to 400,000 between June and September.66 The insurrection was heavily reliant on Allied arms deliveries, but weapons were distributed on a highly selective basis. Even Frenay, a man much closer to Gaullism than communism, complained that until shortly before D-Day only de Gaulle’s direct representatives, who were committed to attentism rather than action, received vital radios, money and arms.67 Furthermore, although parachute drops accelerated68 supplies were still inadequate, something ascribed to the ‘visceral distrust’ the US had of the resistance.69

Corsica offered a glimpse of liberation by people’s war (as opposed to Operation Torch). The island was jointly occupied by German and Italian troops. When Mussolini fell, and the Italian government switched sides, the broad communist-initiated resistance movement moved into action. Partisan bands, in alliance with Italian troops, confronted the Wehrmacht and between 9 September and 4 October 1943, killed a thousand Germans (for a loss of 170 maquis).70 An uprising in the capital, Ajaccio, saw the election by mass meeting of leaders who refused to deal with any Corsican equivalent of Darlan:

‘We can’t mount an effective defence of the island unless proven patriots take command of the levers of power. We can’t trust a local government that did nothing to resist in 1940 … Let’s kick out the Vichyists!’71

De Gaulle was dismayed, not because of the rejection of Vichy, but because he was not in control. He announced that he did not wish to ‘see this precedent followed tomorrow in metropolitan France’.72 This difference between his war and that of the Corsicans, was played out on a grander scale during the liberation of Paris.

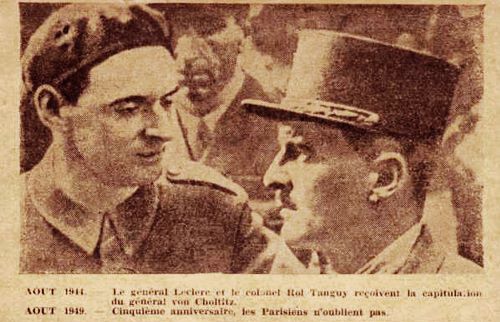

By August 1944 Nazi authority was disintegrating in the French capital in the face of a restless population.73 De Gaulle feared the resistance would free Paris before imperialist forces could reach it. When mass strikes of police, postal and metro workers erupted in mid-August74 de Gaulle ordered them to: ‘Return to work immediately and maintain order until the Allies arrive.’75 This command was ignored, and on 19 August a general insurrection began. Headed by Rol-Tanguy, a communist veteran of the Spanish civil war, 20,000 fighters (of whom only one tenth were armed76) freed the capital over an eight-day period.

The German commander, von Choltitz, was under orders to demolish Paris rather than lose it. Despite being a veteran of Stalingrad, and a man who had wreaked horrific carnage upon Warsaw,77 he realised this policy could not be implemented and that a more likely outcome would be that his forces would be trapped by the resistance and destroyed. At the critical moment Gaullist representatives threw von Choltitz a lifeline. Despite the Allied policy of unconditional surrender, they offered him a truce. He could evacuate in good order if he promised not to sack the town. Accordingly, the resistance was ordered to ‘cease fire against the occupier’. Its leaders were outraged, one writing that:

‘It was impossible to imagine a greater divorce between the action sustained by the masses and the coterie which had positioned itself between them and the enemy.’78

In the confusion, the Germans regained the upper hand for the first time. On the night of 20/21 August, 99 resistance fighters lost their lives as against five Germans.79 So the next day the uprising resumed and completed the job that had been so dangerously interrupted. It was only on the evening of 24 August that regular French troops (General Leclerc’s Second Armoured Division) reached the heart of the city. The final tally for the liberation of Paris was 1,483 French lives compared to 2,788 Germans.80

Now that the hated enemy had been disposed of, would former differences disappear in the glow of national unity? Not at all! While the triumphant resistance waited for de Gaulle at the Hotel de Ville, the symbol of Parisian revolt for three centuries, the brigadier-general was elsewhere. First he met von Choltitz’s aide-de-camp, then leading financiers, and then the Director of the Bank of Indochina, before heading to the War Ministry.81 Only after greeting the Parisian police, who had helped the Nazis maintain order, did he deign to visit the Hotel de Ville.82 De Gaulle did not use the occasion to congratulate the fighters, but to complain that Rol-Tanguy had had the temerity to receive the German surrender as an equal alongside the ‘legitimate’,‘regular’ soldier, Leclerc.83

This was a foretaste of things to come. Three days later, de Gaulle met the resistance again. According to his own account he told the meeting:

‘The militias had no further object. The existing ones would be dissolved [and] after having made note of the accordant or protesting observations of the members of the [CNR] I put an end to the audience.’84

It was not long before the resistance was disarmed. Although this was less violent than in Greece, the process was essentially the same. With the PCF, the main party of the resistance, accepting Stalin’s view that France lay in the Western capitalist camp, its fighters simply accepted de Gaulle’s demands.85

The different conceptions of the Second World War found further expression on the very last day of the war in the West. Amidst the celebrations on 8 May 1945 French troops opened fire on jubilant crowds in Sétif, Algeria, killing thousands.

It might seem that French imperialism had vanquished the people’s war completely, yet the impact of the latter was long-lasting. In the words of a resister, Stéphane Hessel, the CNR programme of 1944 ‘set the principles and values that formed the basis of our modern democracy’ with its wide-ranging reforms in the economy, welfare and education. In 2010 Hessel suggested that despite the passage of 65 years it required the current economic crisis to threaten the final vestiges of that heritage.86 This statement is true for most of Western Europe, where a post-war ‘social democratic consensus’ prevailed after 1945, and is today being fought over once more.

Britain: They Myth of Unity

Unlike France, Britain was not occupied by the Nazis. Therefore no radical resistance movement developed independently of an official government-in-exile. Hints of class tension were smoothed over. Thus, on the eve of war, when Labour’s Arthur Greenwood rose to denounce the arch-appeaser and Tory PM, Neville Chamberlain, dissident Tory MPs shouted ‘Speak for England’, while Labour MPs shouted ‘Speak for the workers’.1 In 1940 both combined to back a coalition with Churchill, as new Prime Minister. He affirmed:

‘This is not a war of chieftains or of princes, of dynasties or national ambition; it is a war of peoples and of causes,’2 and from Labour’s ranks the former union leader Bevin promised that ‘British Labour would not fight an imperialist war’.3

National harmony was also the theme of Britain Under Fire, a pictorial record of the blitz. It was fronted by a photo captioned ‘their Majesties outside Buckingham Palace … subject to identical trials and chances’.4

This heart-warming picture seemed to be confirmed when their Majesties visited the wreckage of Southampton. Journalists reported: ‘excited multitudes [who] lined the wintry streets which re-echoed to volley after volley of cheers and repeated cries of “God save the King”.’5 However, Southampton’s indefatigable Mass Observation volunteers, who looked past the media hype to gauge the popular mood, considered this comment more typical: ‘If they gave new furniture, good food and no fuss, we’d be truly grateful.’6

The nature of modern warfare meant that even without occupation British people experienced the disjuncture between imperialism and their own needs in a way not entirely dissimilar to France. As one writer put it:

‘The Front is not a distant battle field [but] part of our daily lives; its dug-outs and First Aid posts are in every street; its trenches and encampments occupy sections of every city park and every village green ….’7

In London the Blitz threatened to dispel the mirage of unity. A senior diplomat noted privately that in government circles:

‘Everybody is worried about the feeling in the East End, where there is much bitterness. It is said that even the King and Queen were booed the other day when they visited the destroyed areas.’

He was therefore mightily relieved when the Luftwaffe targeted the much wealthier West End: ‘if only the Germans had had the sense not to bomb west of London Bridge there might have been a revolution in this country. As it is, they have smashed about Bond St and Park Lane and readjusted the balance.’8

To make the myth that everyone, ‘however rich or privileged, was in it together’9 plausible required the cultivation of amnesia. On becoming PM Churchill warned his colleagues:

‘If we open a quarrel between the past and the present, we shall find that we have lost the future’.10

He was right to be cautious. He had selected a Cabinet that included notorious appeasers, such as Chamberlain and Halifax, while 21 of the 36 ministerial posts went to people who had served under the previous PM.

Churchill’s cupboard had its own skeletons, too. After visiting Mussolini in 1927 he wrote he ‘could not help being charmed, like so many other people have been, by his gentle and simple bearing and by his calm, detached poise’. He told the inventor of fascism that, ‘[i]f I had been an Italian, I am sure that I should have been whole-heartedly with you from start to finish in your triumphant struggle against…Leninism’.11 Nine years later, during the Italian aggression against Abyssinia, Churchill opposed sanctions against Italy and described the Hoare-Laval pact (an attempt to appease the fascists by handing much of the country over), as ‘a very shrewd, far-seeing agreement …’.12 Nothing Mussolini did could dissuade Churchill from his admiration. Despite the bitter fighting in North Africa that culminated in the Battle of El Alamein, when the Duce fell in 1943 the British PM swore that:

‘Even when the issue of the war became certain, Mussolini would have been welcomed by the Allies’.13

Evidently, determined action against fascism was not his primary motivation during the Second World War.

Neither were the rights of small nations a factor. We shall consider his contemptuous dismissal of Indian nationalism later, but what he had said about the demand for Irish independence in 1921 was also revealing:

‘What an idiotic and what a hideous prospect is unfolded to our eyes. What a crime we should commit if, for the sake of a brief interval of relief from worry and strife, we condemned ourselves and our children after us to such misfortunes. We should be ripping up the British Empire.’14

Therefore, Eire ‘must be closely laced with cordons of blockhouses and barbed wire; a systematic rummaging and question of every individual must be put in force’.15

Yet Churchill was strongly against appeasing Hitler and his ‘rule of terrorism and concentration camps’.16 His opposition to the Führer was unwavering, but only because Germany directly threatened Britain’s power.17 Churchill’s wartime speeches are justifiably famous, yet the familiar ringing phrases are lifted out of context and key sentences left incomplete. After every stirring appeal there was a reference to Empire. Here are a few examples:

I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat … for without victory there can be no survival – let that be realized – no survival for the British Empire, no survival for all that the British Empire has stood for.18

The Battle of Britain is about to begin. Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilisation. Upon it depends our own British life and the long continuity of our institutions and our Empire.19

Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duty and so bear ourselves that if the British Commonwealth and Empire lasts for a thousand years, men will say, ‘This was their finest hour’.20

Churchill was not as openly blunt as Amery who declared, once the defensive Battle of Britain had been won, that ‘The Battle of Empire comes next’.21 He did insist, however:

‘We mean to hold our own. I have not become the King’s First Minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire.’22

The imperialist character of the British government’s war was not simply a matter of personal predilection but was structured by grand strategy past and present. For centuries overseas colonies had required a strong Royal Navy, and the military budget was apportioned accordingly.23 Next in line came the RAF; while the army, the key element in any war with a continental power like Germany, came a poor third. Thus in the decade 1923–1933 the fleet took 58 percent of spending, the air force 33 percent and the army just 8 percent.24 When the Second World War began only 107,000 of Britain’s 387,000 troops were stationed at home.25 So the Expeditionary Force sent to the Continent could provide no more than auxiliary support to sit out the phoney war with the French. When this ‘Sitzkrieg’ ended in 1940, it had to scramble from the beaches of Dunkirk.

After this there was little choice but to try and wear down the German war machine from afar. One historian suggests it was essential ‘to avoid the risk of any confrontation with the German Army anywhere’.26 Skirmishes with the Wehrmacht were therefore by accident rather than design. One example was Norway, which Britain had intended to seize before the Nazis, but found on arrival to be already occupied. London’s chief land operation was far away from Europe, in the Libyan desert defending the route to India from Italians. And only when the latter called in Rommel’s Panzer divisions did engagement with the German army occur there.

A new opportunity to confront Germany on more advantageous terms arose after 1941 when Hitler attacked Russia and the USA joined the war. With 240 Nazi divisions fighting in the East (as compared to just 50 guarding the West), Stalin begged for soldiers to be sent across the Channel to open a second front. When Britain prevaricated some said it was happy ‘to fight to the last drop of Russian blood’. Churchill’s petulant, though technically accurate, reply was that the Russians ‘certainly have no right to reproach us. They brought their own fate upon themselves when by their pact with Ribbentrop they let Hitler loose on Poland and so started the war… .’27

Further, he accused the Soviets of following ‘lines of ruthless self-interest in disregard of the rights of small States for which Great Britain and France were fighting as well as for themselves …’.28 This was rich coming from a government which postponed the second front on the ground that British troops were ‘spread across a distance of some 6,300 miles from Gibraltar to Calcutta’,29 and:

We have to maintain our armies in the Middle East and hold a line from the Caspian to the Western Desert … Great efforts will be needed to maintain the existing strength at home while supplying the drafts for the Middle East, India, and other garrisons abroad, e.g. Iceland, Gibraltar, Malta, Aden, Singapore, Hong Kong ….30

No-one was convinced when Churchill tried to pass off Operation Torch, the landing in French North Africa, as a ‘full discharge of our obligations as Allies to Russia.’31

Britain’s chief strategy bore a feature typical of imperialist war – contempt for human life, and civilians in particular. It involved ‘area bombing’ – the use of the RAF to flatten German cities rather than hit specific military targets. This tactic was predicted in 1932 by the then PM, Baldwin. He declared laconically that because ‘the bomber always gets through’:

‘The only defence is in offence, which means that you have to kill more women and children more quickly than the enemy if you want to save yourselves. I just mention that … so that people may realize what is waiting for them when the next war comes.’32

Despite initial doubts, Churchill turned to this method in 1940 because:

‘We have no Continental Army which can defeat the German military power [but] there is one thing that will bring him back and bring him down, and that is an absolutely devastating, exterminating attack by very heavy bombers.’33

Bomber Command translated this into practice:

‘the aiming-points are to be the built-up areas, not, for instance, the dockyards or aircraft factories … This must be made quite clear … .’34

Three-quarters of bombs fell on civilian targets,35 the ultimate intention being to render 25 million homeless, kill 900,000, and injure one million more.36

It has been alleged, in mitigation, that practical factors made area bombing unavoidable. German anti-aircraft defences made daylight raids on military installations too costly, but night-time attacks could not hit precise military targets. Big cities were therefore a more realistic goal.37 Nonetheless, the technical capabilities of the British military were shaped by Empire and were inseparable from it.

Even if area bombing had been tenable as the only viable tactic, it lost all credence after the Normandy landings in the summer of 1944. Yet it carried on relentlessly under Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris of Bomber Command. He boasted that his boys had ‘virtually destroyed 45 out of the leading 60 German cities. In spite of invasion diversions we have so far managed to keep up and even exceed our average of two and a half cities devastated a month… .’38 On 13 February 1945 British and US bombers generated a firestorm that destroyed Dresden’s cultural centre, the Altstadt, along with 19 hospitals, 39 schools and residential areas. Key military and transport installations remained intact. Between 35,000 and 70,000 people died, of whom just 100 were soldiers.39

The bombing campaign only ceased when Churchill realised nothing would be left to plunder after victory:40

‘… we shall come into control of an utterly ruined land. We shall not, for instance, be able to get housing materials out of Germany for our own needs because some temporary provision would have to be made for the Germans themselves.’41

Belatedly he argued for ‘more precise concentration upon military objectives, such as oil and communications behind the immediate battle-zone, rather than on mere acts of terror and wanton destruction, however impressive’.42

Could it at least be argued that all this suffering speeded the end of Nazism? It was claimed that area bombing would break morale and slow armaments production. But Germany’s output actually rose under the hail of bombs: from an index of 100 in January 1942, to 153 in July 1943, and 332 in July 1944.43 Far from morale being broken, Germany’s population was steeled. Hitler’s Armaments Minister wrote that, ‘the estimated loss of 9 percent of our production capacity was amply balanced out by increased effort.’44 Max Hastings concludes that:

‘Bomber Command’s principal task and principal achievement had been to impress the British people and their Allies, rather than to damage the enemy’.45

When it came, German defeat was largely due to the Red Army, which fought the most crucial battles, at Stalingrad and Kursk (1942–43). Soviet military deaths amounted to 13.6 million out of 20 million under arms (an attrition rate of 68 percent). British military strength was 4.7 million and its forces endured 271,000 deaths (an attrition rate of 6 percent).46 Refusing to open a second front until Russia was winning on its own (and marching towards Western Europe), plus the deliberate slaughter of civilians to minimal military effect, were chilling evidence of the nature of the war being fought by Churchill. His government was driven, above all, by the need to impress friend and foe of Britain’s great power status.

The motives of most British people were not the same as their government’s. A variety of writers expressed the notion that:

‘The world is confronted by a clash between two irreconcilable ideals: humanism and anti-humanism.’47

The war was about ‘accepting a way of life determined by love rather than power’.48 Mass Observers found people largely free of the jingoism of the First World War:

‘There is no gushing, sweeping-away dynamo of “patriotism”, no satisfied gush of the primitive, the hidden violent, the anti-hun and “destroy the swines”.’49

This should not be taken as cool detachment – quite the contrary. In 1938, 75 percent of those asked about foreign affairs were either bewildered or could make no comment. In 1944 85 percent had definite views and ‘an overwhelming majority are in favour of international cooperation …’.50

Ordinary people remembered that during the 1930s appeasement abroad walked hand in hand with attacks on living standards at home. Therefore, when appeasement was discredited they wanted to confront the home-grown ‘little Hitlers’ who had conducted a blitzkrieg against labour.51 In Glasgow a Mass Observation study of 1941 reported:

The workers do not believe that the employers care a fig for the men, or for anything else than saving their skins now by at last producing the vessels, metals, cargo discharges; and … a surprising number of men do not even believe that the employers really care about saving their skins, because ‘they would be just as happy under Hitler’ – here left wing propaganda has certainly had an effect in equating the employer with the friend of Fascism.52

Based on experience after the 1914–18 war many feared what the Second World War might bring. Ritzkrieg, a satirical book of 1940, warned that if the establishment had its way once more:

‘The People’s War was to have become the Best People’s War, and the peace to follow it… a return to Olde England and the aristocratic regime, without the alteration of one jot or title.’53

Mass Observation found it was not that ‘workers are against the war or for peace. They want it as much as anyone… [but they] are also having a war of their own … .’54 And this was the crux of the matter. Most were not fighting to defend the Britain of the 1930s or colonial rule. In 1944, a Mass Observer noted, ‘[t]he things that people want put right first are the things that went wrong last time … Chief among these is certainty of a job, and then certainty of a decent house to live in.’55

So in place of area bombing and Empire, ordinary people focused on a fight for justice and decency. Remarkably, the inhabitants of cities most damaged by the Blitz were least favourable to reprisals. In London where 1.4 million (one in six) were rendered homeless, only a minority wanted to fight back in kind.56 Individual comments recorded by Mass Observers showed how ordinary people’s views clashed with the government’s approach:

PEACE AIMS: an armed League of Nations to precede Socialism.

RECONSTRUCTION AT HOME: every man who has been a worker should be allowed enough to live in comfort for the rest of his life.

THE END OF THE WAR: financiers… are running the war, and when they have made as much money as they want, the war will stop.57

The Labour Party sought to bridge the widening gap between imperial war and the people’s war, as this rather confusing contribution by Bevin shows:

‘England’s experience in the realm of giving liberty is probably the greatest. We have built up a great empire over the last three or four hundred years … .’58

However nonsensical, such statements do show an awareness of the two wars.

British communism’s position was even more complicated. At the outbreak of war Harry Pollitt was its leader and an enthusiastic advocate of people’s war:

Whatever the motive of the present rulers of Britain and France… [T]o stand aside from this conflict, to contribute only revolutionary sounding phrases while the fascist beast rides roughshod over Europe, would be the betrayal of everything our forbears have fought to achieve in the course of long years of struggle against capitalism.59

Since this contradicted the Hitler-Stalin Pact, Pollitt was replaced. The October 1939 CP manifesto called for:

‘a united movement of the people to compel the immediate ending of the war … to bring down the Chamberlain government, to compel new elections and to prepare the establishment of a new government which shall make immediate peace’.60

In June 1941 Moscow’s line changed again and the Party reverted to supporting anti-fascist struggle, but with all references to ‘struggle against capitalism’ deleted. Pollitt returned to promote unity with ‘all who are for Hitler’s defeat. Our fight is not against the Churchill Government…Now it is a people’s war.’61 His definition does not accord with the one used in this book, but these alternating CP interpretations shows how difficult it was to reconcile people’s war and imperialist war.

The bosses were divided too. This emerged in a debate over Joint Production Committees, bodies set up to encourage worker-employer collaboration. The director of the Engineering Employers’ Federation insisted he ‘was not going to be a party to handing over the production of the factory and the problems concerning production to shop stewards or anyone else’.62 Another managing director took the contrary view:

‘If industry doesn’t plan for revolution, there’ll be revolution … And we can only avoid it by anticipating it, by meeting the needs of the people and the times, by taking the great changes that are going to be forced on us anyway if we don’t do it ourselves.’63

On the workers’ side the Manchester District Committee of the Amalgamated Engineering Union (AEU) warned perceptively that:

we are working under a capitalist system, more highly organised for exploitation, even than in peace time. Every advantage that the employers can secure from collaboration and relaxation [of trade union vigilance] will be, and is being, ruthlessly acquired, throughout the industry … For the workers it is truly a war on two fronts, or, if you like, back and front.

Despite these misgivings the conclusion drawn was that Joint Production Committees should be supported to increase production and prevent a Nazi victory.64 The conundrum is perhaps explained by this opinion picked up by a Mass Observation volunteer in 1944:

‘Away from selfishness. In the factories of Britain men and women worked long hours, not for a boss, not for any one person’s private advantage, but for everyone … .’65

The strong belief that the people’s will could be impressed upon the Second World War did not depend on ideas alone. With 30 percent of the male workforce called up,66 and an unquenchable demand for industrial output, ordinary people had a new-found economic clout and confidence. The signs of this were everywhere. When homeless Londoners invaded the underground stations to use them as shelters the government objected, but eventually gave in.67 Calder recounts how:

Father John Groser, one of the historic figures of the ‘blitz’ took the law into his own hands. He smashed open a local depot. He lit a bonfire outside his church and fed the hungry. There wasn’t a cabinet minister or an official who would have dared to stand in his war or to challenge this ‘illicit’ act. Similarly, in another London borough a local official of the Ministry of Food found a crowd of homeless uncared for. He broke open a block of flats. He put them in. He got hold of furniture by hook or by crook, he got the electricity, gas and water supply turned on, and he brought them food.68

It was in industry that the clash between the two wars was most strongly expressed. The CP’s drive for maximum production led it to strive ‘might and main to avoid stoppages’69 and industrialists gratefully rewarded it with positive testimonials.70 There was an alternative analysis expressed. At one shop stewards’ meeting a speaker referred to the appeasement of Hitler at Munich in 1938:

‘There were Municheers still in the Government and there were Municheers still running business … .’71

This distrust was clearly a common view, and the public often took the side of the workers during industrial disputes.72

While the CP’s links with Russia gave it a rising prestige that more than compensated for losses sustained by opposing strikes, its stance opened the way for other political forces to channel workers’ discontent. The Trotskyist movement was miniscule but its position on the war enabled it to lead a series of strikes far beyond its numbers.73 According to the movement’s historians, British Trotskyists ‘differentiated between the defencism of the capitalists and that of the workers, which “stems largely from entirely progressive motives of preserving their own class organisations and democratic rights from destruction at the hands of fascism”.’74

There were 900 strikes in the first months of war. By 1944 the figure had risen to 2,000 (with 3.7 million days of lost production). This was in spite of the combined efforts of Labour, the CP, and Regulation 1AA which, by virtually outlawing stoppages has been described as ‘… the most powerful anti-strike weapon possessed by any government since the 1799 Combination Acts’.75 One historian writes that: ‘the tempo of activity and discussion increased dramatically, sometimes giving a toehold to some extreme left political agitators [though] it was at this point too early to speak, as some of these agitators did, of a “second front at home”.’76

Radicalism never matched that seen in the First World War because of the ‘contradictory duality’ of the Second World War.77 Nevertheless, the very idea of a ‘second front at home’ spoke volumes.

Britain’s Middle East Army also experienced war in parallel. The mission was to protect Egypt and the sea route to India, the ‘jewel in the Crown’ of the Empire. Its commanders have been described in these terms:

Almost to a man the officers were tall, upper-class Englishmen who came to a formal dinner wearing the same skin-tight crimson trews that had seen service in the Crimea. They had almost all attended the same top six English public schools … The Nottingham-based Sherwood Rangers under the Earl of Yarborough had even tried to take with them to Palestine a pack of foxhounds belonging to the Brocklesby Hunt.78

The playing fields of Eton proved a poor preparation for total war. The fall of Tobruk was, after Singapore, the largest British capitulation in the Second World War,79 and German panzers came within 10km of Cairo. The morale of Britain’s ‘desert rats’ had to be rapidly reconstituted, so Field Marshal Montgomery motivated his troops by giving them a purpose for risking their lives. This was explained to them by the newly founded Army Bureau of Current Affairs (ABCA), a body largely run by radically-minded tutors committed to making the Second World War a people’s war.80 The King’s Regulations forbad political activity by soldiers, but in the highly charged atmosphere of the time the borderline between current affairs and politics was easily blurred.

A rank and file soldier’s movement developed and found its voice in a profusion of information sheets and wall newspapers. They were for a people’s war as opposed to an imperialist one. For example, the founding statement of the Soldiers’ Anti-Fascist Movement said:

We shall campaign for a maximum war effort, expose slackness and reactionary influences in the fighting services. Our news on international affairs will be from the anti-fascist viewpoint… We shall do all we can to speed victory over fascism, victory that must be followed by a People’s Peace.81

The very fact of soldiers openly discussing military policy was insubordination, as was the widespread demand for a second front in opposition to Churchill’s foot-dragging.82

However, it did not stop there. Allied rhetoric asserted this was a fight for democracy. If so, some soldiers concluded, democracy could and should be practiced by those doing the fighting. A mock soldiers’ parliament was set up in Cairo in late 1943. Although others appeared elsewhere, what made the Egyptian experiment unique was the lack of officer influence. It was a ‘parliament of Other Ranks in the tradition of the English Revolution’.83

The tenor of the proceedings can be gauged from the Bills it ‘passed’. The first called for public ownership of businesses. On 1 December the distributive trades were nationalised. An Inheritance Restriction Bill followed.84 There were also plans to grant independence to India, abolish private schools and nationalise coal, steel, transport and the banks.85 An ‘election’ by mass meeting was held. The joint Labour/CP ticket won 119 seats, Commonwealth (a new party opposing the Churchill-led coalition from the left) 55, Liberals 38 and Conservatives just 17.86 Simultaneously, in the ‘real’ parliament at Westminster, a move to permit off-duty soldiers to engage in politics was proposed by no less than a Tory MP. He argued it ‘could do no harm and might do a great deal of good, and which ought to be his by right – that is to say if we are indeed fighting for democracy’.87

Unsurprisingly this ‘real’ proposal was defeated. An imperial war requires a tame army that unquestioningly follows ruling class orders. The advocates of people’s war had to be silenced. In February 1944 the Commander in Chief of Middle East Forces ordered:

‘that the name of parliament must not be used; that there must be no publicity of any kind, even war correspondents being excluded, and that the proceedings must be supervised and directed by an Army education officer.’88

When this was read out to the Cairo Parliament the soldiers protested 600 to one. That one vote was the brigadier who had presented the order. Members of the organising committee were immediately transferred, as was the new ‘Prime Minister’. The man who moved bank nationalisation, Leo Abse, was spirited away under ‘open arrest’, and deported back to Britain.89

This Forces Parliament was broken up and the old order restored. However, discontent bubbled up again. When news of Labour’s election victory in Britain reached Egypt in 1945, soldiers stopped saluting officers for about ten days.90 Real fury erupted after Victory over Japan Day, August 1945, when soldiers realised that defeating the Axis had not ended the war. If the government had considered the Second World War an anti-fascist war, demobilisation should have begun the day the enemy capitulated. However, Labour refused to bring its weary troops home. Bevin told the Commons in November 1945 that:

‘It is the intention of his Majesty’s Government to safeguard British interests in whatever part of the world they may be found.’91

British troops must continue to fight for the British Empire, and for the empires of those yet unable to fight for themselves – France and Holland. Their Vietnamese and Indonesian colonies would have to be violently restored to the ‘rightful’ owners.92

Some servicemen had other ideas. They struck rather than sail Dutch soldiers to Indonesia.93 700 RAF briefly mutinied at Jodhpur, India.94 By the end of 1945 protests had occurred in Malta95 followed by Ceylon, Egypt and again India96 where a new Forces Parliament had been reconstituted.97 In March 1946 a radar operator was sentenced to ten years in connection with RAF strikes in Singapore, and in May there was a full-scale mutiny in Malaya which resulted in a string of court martials.98

Britain’s industrial strikes and military mutinies, while revealing the existence of parallel wars, were limited affairs. More often the conflict between those giving orders and those carrying them out was masked, existing as divergent ideas held in people’s heads. Indeed, many ordinary citizens just wanted to muddle through without choosing between either of the two wars. Rather than politics or strategy, the driving force for the ‘poor bloody infantry’ has been described as frequently a combination of ‘coercion, inducement and narcosis’.99 And the sentiment of this Yorkshirewoman was doubtless commonplace among civilians:

We used to watch our bombers going out, hundreds at a time at regular intervals … I would say, ‘They’ve gone over the edge of England and many won’t ever come back. They are just going out there to die.’ And then we thought of all the innocent people over there who were going to be destroyed by us. When was it going to end? It was all so hopeless – and for what? You felt the futility of it all and the sorrow for all the human beings involved in this hellish war, and wished with all your heart it was over.100

Nonetheless, there were clear proofs that large numbers, probably the majority, saw the war very differently to the establishment. One example was the reception accorded to the 1942 Beveridge Report that laid the basis for the post-war welfare state and National Health Service. Calder is correct to argue that ‘the scheme was nothing like so revolutionary as Beveridge, and some of his admirers, liked to present’.101 For example, contributions to the scheme were flat rated so the poor paid as much as the rich, and it provided no more than a safety net. Nonetheless, ‘after the first glare of limelight, the Government went to extraordinary lengths to stifle all official publicity for the report’.102 A summary written by Beveridge for servicemen was withdrawn two days after being issued103 on the grounds that the Report had become ‘controversial and therefore contrary to King’s Regulations’,104 while Churchill regarded the report as a distraction from the fighting.

The fascinating thing is that in spite of all this, as Mass Observation discovered, ordinary people took it to be ‘a symbol of Britain’s war aims’.105 No other official government publication has sold 635,000 copies or had the approval of 90 percent of those polled.106 Even The Times pointed out that the public ‘refuses to accept the false distinction between these aims and the aim of victory’.107

The ultimate purpose of the war – a better, more equal, fairer world as embodied in a welfare state, or a return to pre-war structures – was the main issue of the 1945 general election. Churchill plainly hoped for a ‘khaki election’ such as the one that returned the First World War’s Prime Minister, Lloyd George. Churchill called on the public to ‘Vote National’. The brunt of his keynote speech was directed in veiled terms against welfare:

‘Here in old England … in this glorious island, the cradle and citadel of free democracy throughout the world, we do not like to be regimented and ordered about and have every action of our lives prescribed for us.’ Labour’s welfare state, he predicted, ‘would have to fall back on some form of Gestapo’.108

In his reply Attlee appealed to the concept of a ‘people’s war’.

I state again the fundamental question which you have to decide. Is this country in peace as in war to be governed on the principle that public welfare comes before private interest?… Or is the nation to go back to the old conditions…? I ask you, the electors of Britain, the men and women who have shown the world such a shining example of how a great people in the face of mortal danger saved itself, to give Labour power to lead the way to a peaceful world and a just social order.109

Even if Labour failed to deliver on many of its promises, the significant point is that it claimed the mantle of a people’s war. And the results were eloquent. Churchill’s Conservatives dropped to 213 MPs, while the Labour Party romped home with 393 MPs, to form its first majority administration. The coalition government (including Labour) had fought an imperialist war, but in the minds of millions of voters the goal of the conflict had been quite different.

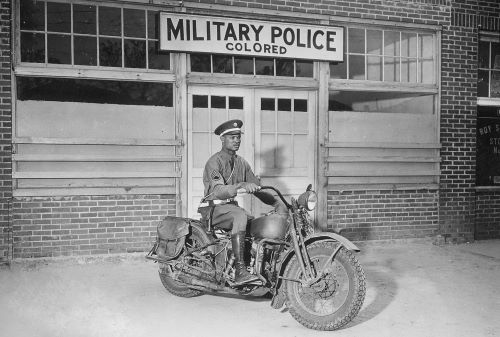

U.S.A.: Racism in the Arsenal of Democracy

Overview

The USA made a major contribution to the outcome of the Second World War. 405,000 Americans lost their lives and a staggering $330 billion was spent.1 If the death toll pales in comparison with that of the Soviet Union, the USA’s role as a source of arms was outstanding. Through lend-lease it supplied mountains of military equipment and food. The Soviet Union gained about one tenth of its hardware from the US,2 and Britain twice as much.3

In some respects the position of the USA did appear different to its Allies. It lacked extensive colonies4 and more readily spoke the language of people’s war. In 1940 President Roosevelt made a famous speech claiming the USA was the ‘great arsenal of democracy’. He castigated the Nazis for having ‘proclaimed, time and again, that all other races are their inferiors and therefore subject to their orders’.5 A week later he declared ‘national policy’ was ‘without regard to partisanship’ and involved ‘the preservation of civil liberties for all’.6

However, the differences between the USA and its Allies should not be exaggerated. Washington’s involvement in the Second World War was part of what Ambrose has called its ‘rise to globalism’:

In 1939 … the United States had an Army of 185,000 men with an annual budget of less than $500 million. America had no military alliances and no American troops were stationed in any foreign country … Thirty years later the United States had [a defence budget of] over $100 billion. The United States had military alliances with forty-eight nations, 1.5 million soldiers, airmen, and sailors stationed in 119 countries.7

If, prior to the Second World War, America had followed a different path to the European powers, it was one of internal rather than external colonisation, not just through the drive West and obliteration of Native Americans, but through the exploitation of enslaved Africans shipped to its soil. Therefore, on the question of whether the US war effort took on an imperialist or people’s character, a crucial test was the domestic issue of race, which has been called ‘the American obssession’.8

The Japanese

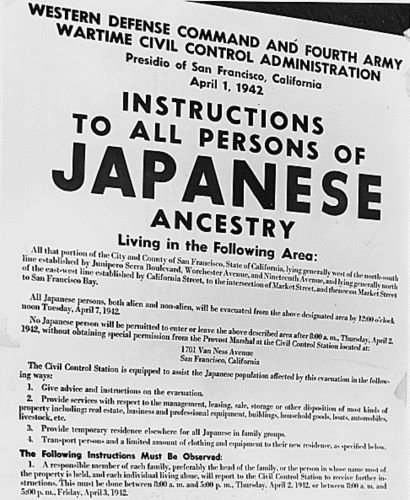

This first arose in relation to the Japanese. Although the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor was the brainchild of Tokyo, Federal authorities turned on the Japanese in America. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 (March 1942) interned ‘all persons of Japanese ancestry’ in the Western Defense Command area (California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona).9 This affected 120,000 people of whom 70,000 were American citizens.10

Asians had been exploited on America’s western seaboard since the mid-nineteenth century, and racism was encouraged to both keep their wages down and divide all workers, white and non-white, amongst themselves. The Japanese were a common target. When running for President in 1912 Woodrow Wilson declared that the Japanese could ‘not blend with the Caucasian race,’ and a few years later the Californian governor insisted on ‘the principle of race self-preservation’. In a notorious court case one man was refused naturalisation simply because he was ‘clearly of a race which is not Caucasian’,11 and by 1924 that precedent had solidified into national law. To maintain ‘racial preponderance’ only ‘free white persons’ were now eligible.12

The architect of Order 9066, Western Defense Commander DeWitt, was clear his motivation was genetic:

The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born in the United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship, have become ‘Americanized’, the racial strains are undiluted. To conclude otherwise is to expect that children born of white parents on Japanese soil to sever all racial affinity and become loyal Japanese subjects.13

Administrators of Order 9066 thought it an over-reaction, but they accepted the view that: ‘the normal Caucasian countenances of such persons enable the average American to recognize particular individuals by distinguishing minor facial characteristics [but] the Occidental eye cannot readily distinguish one Japanese resident from another.’ This made the ‘effective surveillance of the movements of particular Japanese residents suspected of disloyalty’ virtually impossible.14

The public justification for Order 9066 was military necessity. DeWitt loudly claimed that the US Japanese were broadcasting sensitive US intelligence, though he knew it to be untrue,15 and the notoriously reactionary FBI boss, Hoover was aware the claim was pure fiction.16 To get round the lack of evidence an amazing proof, worthy of Donald Rumsfeld, was advanced:

‘The very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken.’17

Although the authorities suggested internment was popular, secret polling in the areas affected showed only 14 percent favoured the strategy.18 People could see through the scare-mongering of politicians and press.

Order 9066 was implemented using methods reminiscent of Nazi ‘aryanisation’. Japanese were herded into former stables, cattle stalls and pigpens before transfer to longer term ‘relocation centers’ like the bleak camp at Minidoka, Idaho.19 The term ‘concentration camp’ had been quietly dropped. Taking little more than they could carry, they lost homes and property worth $400 million.20 A riot in one camp was quelled by soldiers who killed two and wounded many more. When a doctor revealed protesters had been shot in the back he was sacked.21

Internment found critics in unexpected quarters. The director of the War Relocation Authority was dismayed by the policy he had to implement. He believed that it ‘added weight to the contention of the enemy that we are fighting a race war; that this nation preaches democracy and practices racial discrimination’.22 The victims of Order 9066 also pointed out the hypocrisy of the government’s stance:

‘Although we have yellow skins, we too are Americans. [So] how can we say to the white American buddies in the armed forces that we are fighting for the perpetuation of democracy, especially when our fathers, mothers and families are in concentration camps, even though they are not charged with any crime?’23

The difference between the way the USA fought its war in Europe and Asia also showed the influence of race. One veteran remembered how his drill instructor declared:

‘You’re not going to Europe, you’re going to the Pacific. Don’t hesitate to fight the Japs dirty’.24

A war correspondent recalled:

‘We shot prisoners in cold blood, wiped out hospitals, strafed lifeboats … finished off the enemy wounded.’25

Sometimes the purpose was merely to extract their gold teeth.26 When the same veteran asked about a shooting he heard, he was told:

‘It was just an old gook woman. She wanted to be put out of her misery and join her ancestors, I guess. So I obliged her.’27

When Britain’s Bomber Command asked the Eighth US Air Force to participate in ‘Operation Thunderclap’ which aimed to kill some 275,000 Berliners, America’s General Cabell protested that such: ‘baby killing schemes [would] be a blot on the history of the Air Forces and of the US’.28 This did not prevent the USA from participating in the bombing of Dresden but the reasons were strategic. Like the British, Senior US commanders were aware that their air forces ‘are the blue chips with which we will approach the post-war treaty table’ and that it was important to ensure ‘Russian knowledge of their strength’.29

In war with Japan the racial overtones were more prominent. ‘Baby killing schemes’ were routine US policy in the Asian theatre, and those who said these were ‘un-American’ were denounced because, as the Weekly Intelligence Review suggested in tones reminiscent of Stanley Baldwin:

‘We intend to seek out and destroy the enemy wherever he or she is, in the greatest possible numbers, in the shortest possible time. For us, THERE ARE NO CIVILIANS IN JAPAN.’30

An example of what this meant in practice was the raid on Tokyo, 10 March 1945. It killed 100,000. Air Chief Curtis LeMay called it ‘the greatest single disaster incurred by any enemy in military history … There were more casualties than in any other military action in the history of the world’.31 US Atomic energy Commission chair, David Lilienthal summed up how the war developed against Japan:

Then we burned Tokyo, not just military targets, but set out to wipe out the place, indiscriminately. The atomic bomb is the last word in this direction. All ethical limitations of warfare are gone, not because the means of destruction are more cruel or painful or otherwise hideous in their effect upon combatants, but because there are no individual combatants. The fences are gone. And it was we, the civilized, who have pushed standardless conduct to its ultimate.32

This is a valid judgement on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Although the US was fully aware that Japan was suing for peace,33 the Secretary of State – Stimson – wanted the atom bomb deployed and ‘the most desirable target would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers’ houses’. One historian adds: ‘Stripped of polite euphemisms, that meant massively killing workers and their families, the residents of those houses.’34

Harry Truman, Roosevelt’s successor, realised the atomic bomb was ‘far worse than gas or biological warfare because it affects the civilian population and murders them by the wholesale’.35 Nuclear bombs killed around 200,000 in the short term, and wiped out the very medical services which might have helped civilian casualties. In Hiroshima:

Of a hundred and fifty doctors in the city, sixty-five were already dead and most of the rest were wounded. Of 1,780 nurses, 1,654 were dead or too badly hurt to work. In the biggest hospital, that of the Red Cross, only six doctors out of thirty were able to function, and only ten nurses out of more than two hundred.36

And the effect of the bomb on people virtually defies description:

The sight of them was almost unbearable. Their faces and hands were burnt and swollen; and great sheets of skin had peeled away from their tissues to hang down like rags on a scarecrow … And they had no faces! Their eyes, noses and mouths had been burned away, and it looked like their ears had melted off.37

The Jews

The ending of the Holocaust is perhaps the most potent argument for the Second World War being a ‘good war’. So what was Allied attitude to the plight of the Jews? When Hitler annexed Austria in 1938 London slapped on visa restrictions to make it difficult for Jews to escape.38 By the outbreak of war only 70,000 of the 600,000 Jews who sought asylum had been accepted.39 After 1939 the door snapped shut, because anyone coming from Axis territory was now branded an enemy alien. Britain’s Foreign Secretary vetoed the rescue of 70,000 Romanian Jews (fully funded by the American Jewish community) because:

‘If we do that, then the Jews of the world will be wanting us to make similar offers in Poland and Germany. Hitler might well take us up … .’40

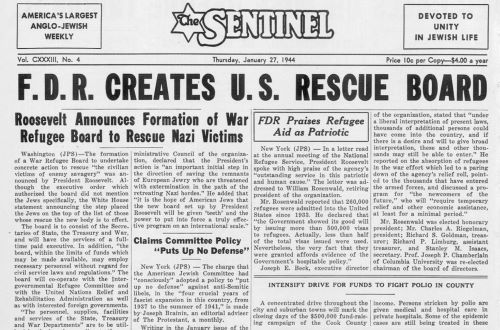

‘Amazing, most amazing position’, exclaimed one American official,41 and this shows that the USA had a better approach. In January 1944 it set up a War Refugee Board which saved up to 250,000 Jewish lives.42 However, before getting carried away it is important to note that the Government provided a mere 9 percent of its funding. The rest came from private sources.43 Moreover, as Wyman makes clear in his excellent book The Abandonment of the Jews, 1944 was very late, and the road to the establishment of the Board had been a rocky one. As early as 1941 the US authorities knew about the extermination taking place in Europe. Indeed, in July 1942 a 20,000 strong assembly in New York protesting at the Holocaust received messages of sympathy from both Roosevelt and Churchill.44

Yet Roosevelt appointed Breckinridge Long, who Eleanor Roosevelt described as ‘a fascist’,45 to oversee immigration rules. His policy was to ‘postpone and postpone and postpone the granting of visas’ and thus ‘delay and effectively stop [immigration] for a temporary period of indefinite length …’46 To assist in this process the USA visa application form was four feet long and:

had to be filled out on both sides by one of the refugee’s sponsors (or a refugee-aid agency), sworn under penalty of perjury, and submitted in six copies. It required detailed information not only about the refugee but also about the two American sponsors who were needed to testify that he would present no danger to the United States. Each sponsor had to list his own residences and employers for the preceding two years and submit character references from two reputable American citizens whose own past activities could be readily checked.47

Then a cruel Catch-22 was introduced. There were no consuls to issue visas in Axis-controlled Europe, but those who escaped from there to places such as Spain and Portugal were deemed to be ‘not in acute danger’ and therefore refused visas.

Such actions led a prominent Jewish Socialist member of the Polish National Council to commit suicide. He explained his decision thus:

The responsibility for this crime of murdering the entire Jewish population of Poland falls in the first instance on the perpetrators, but … by the passive observation of the murder of defenseless millions and of the maltreatment of children, women and old men, [the Allied states] have become the criminals’ accomplices … As I was unable to do anything during my life, perhaps by my death I shall contribute to breaking down that indifference.48

The welcome establishment of the War Refugee Board close to the end of the war pales in significance when set against the USA’s refusal to stop Auschwitz operating. Detailed information about this death camp came from two escapees, Vrba and Wetzler, in early 1944. Wyman shows that up to 437,000 lives could have been saved if Auschwitz’s railways lines and crematoria had been bombed,49 but the War Department declared this ‘impracticable.’50 In fact, between July and October 1944, ‘a total of 2,700 bombers travelled along or within easy reach of both rail lines on the way to targets in the Blechammer-Auschwitz region’,51 and on several occasions the camp actually shook from attacks at nearby installations.

Wyman’s verdict has been hotly debated.52 The counter-argument, that the Western Allies did not wish to be distracted from an exclusive focus on defeating Germany, falls when set against their costly efforts to evacuate Spanish children during the civil war or supply the Warsaw Rising. ‘Humanitarian acts’ seem to have been carried out only when politically expedient. One convinced ‘Rooseveltian’ defends his hero by emphasising the President’s ‘sincere belief that it was essential to put all of America’s resources and his own influence into winning the war’.53 The question is: which war was he trying to win?