Early efforts laid important groundwork for the evolution of the American educational system.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Education in early America was a complex and evolving institution shaped by religious, cultural, economic, and geographic factors. From the earliest English colonies to the post-Revolutionary era, the education of children reflected the priorities and challenges of a developing society. This essay explores the varied nature of childhood education in early America, focusing on the colonial period through the early 19th century, highlighting regional differences, religious influences, gender roles, and the gradual movement toward public schooling.

Laying Foundations

The foundations of American education in the colonial period were deeply shaped by religious motivations and regional variations, particularly between New England and the Southern colonies. In New England, the Puritans were especially concerned with ensuring that children could read the Bible and understand religious doctrine, leading to a widespread belief in the necessity of literacy for all. This religious imperative culminated in the Massachusetts School Law of 1647, commonly referred to as the “Old Deluder Satan Act,” which required towns of a certain size to establish and maintain schools.¹ This act was predicated on the belief that Satan sought to keep people from Scripture, and that literacy was a defense against spiritual ignorance. Thus, early American education was less about secular knowledge and more about religious salvation, though the structure laid down by these laws would form the backbone of public education systems in later centuries.

Educational practices and structures varied significantly in other colonies, especially in the South where large plantations and dispersed populations made the establishment of common schools more difficult. Instead, education was often managed privately among the wealthier classes, with tutors brought to estates or children sent to England for schooling.² This stratified system created a clear divide between the elite and the poor, with the latter frequently receiving no formal education at all. Anglican influence was prevalent in the Southern colonies, but it did not inspire the same communal educational efforts seen among the Puritans. As such, the colonial South lacked a widespread educational infrastructure, and literacy rates lagged behind those of New England well into the eighteenth century.³

The middle colonies presented a more diverse educational landscape, influenced by their ethnic and religious pluralism. Colonists in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey included Dutch, German, Quaker, and other European communities, each establishing schools according to their own cultural and religious customs. The Quakers, for instance, were proponents of universal education and founded some of the earliest coeducational institutions in the colonies.⁴ German-speaking communities often established parochial schools that instructed children in both German and English, maintaining their linguistic heritage while integrating into the colonial framework. These varied efforts created a mosaic of educational experiences, but they also introduced challenges regarding standardization and cohesion, which would become more pressing in the post-Revolutionary period.

One of the most lasting legacies of colonial education was the founding of institutions of higher learning, many of which were established to train clergy and civic leaders. Harvard College, founded in 1636, was the first institution of higher education in the colonies and was intended primarily to prepare ministers for the Puritan community.⁵ Yale, Princeton, and the College of William & Mary followed suit, each tied closely to specific denominations and ideological goals. While initially focused on theology and classical languages, these institutions gradually expanded their curricula to include philosophy, science, and law, laying the intellectual groundwork for the Enlightenment-influenced leaders of the American Revolution. These colleges played a crucial role not only in formal education but in shaping the ideological contours of emerging American identity.

The colonial foundations of education in America were deeply rooted in religious convictions, regional differences, and pragmatic responses to local conditions. The Puritan emphasis on literacy for spiritual well-being contributed to a communal ethos that encouraged public schooling, while the Southern reliance on private tutors and imported education reflected broader socio-economic inequalities. The middle colonies’ diversity fostered innovation and inclusivity but also made systematization difficult. Meanwhile, colonial colleges began the long trajectory toward a more secular and civic-oriented educational mission. Together, these elements created a patchwork educational heritage that would influence American education long after the colonial era ended.

Regional Variations

Colonial America was far from uniform in its educational practices; distinct regional patterns emerged that reflected differences in religion, economy, demography, and geography. Nowhere were these differences more pronounced than between New England and the Southern colonies. In New England, the Puritan emphasis on scriptural literacy and communal responsibility led to a unique educational culture centered around universal schooling. Towns were legally required to provide schools under laws such as the Massachusetts School Laws of 1642 and 1647, which mandated basic education in reading and religious instruction.⁶ The Puritans believed that a literate populace was essential not only for individual salvation but also for maintaining an orderly and godly society. As a result, literacy rates in New England were remarkably high compared to other colonial regions, and education was seen as a public concern requiring collective investment.⁷

By contrast, the Southern colonies developed an education system that was far more private, elitist, and inconsistent. Large plantations and sparse settlements made the establishment of centralized schools difficult, and education was often confined to the children of the wealthy planter class, who hired private tutors or sent their sons to England for schooling.⁸ The Anglican Church, though dominant in the region, did not sponsor widespread educational institutions as the Puritan Congregationalists did in the North. As a result, education in the South remained a privilege rather than a right, and literacy rates—especially among the lower classes, women, and enslaved people—remained low.⁹ The reliance on a plantation-based economy further entrenched educational disparities, making formal learning subordinate to agricultural labor in the lives of many.

The Middle Colonies presented a different case altogether due to their ethnic and religious diversity. Home to Dutch, German, Swedish, Scots-Irish, and English settlers, the region developed a patchwork of educational systems, often tied to religious communities. Quakers in Pennsylvania and New Jersey emphasized practical and moral instruction and were notable for encouraging education for both boys and girls.¹⁰ German settlers often established parochial schools that taught in their native language, preserving cultural identity while also incorporating English instruction.¹¹ The decentralized nature of these efforts meant that while educational opportunities were often available, they varied greatly in quality, language of instruction, and curricular focus. Unlike New England, where town schools were common, and the South, where they were rare, the Middle Colonies were characterized by pluralism and private initiative, offering a wide range of educational experiences.

Urban centers across all regions, such as Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston, provided unique educational opportunities not available in rural settings. These cities supported a variety of institutions, including charity schools, academies, and apprenticeships. Benjamin Franklin’s Academy in Philadelphia, founded in 1751, was especially innovative, offering a curriculum that went beyond classical languages to include mathematics, science, and practical subjects relevant to commercial and civic life.¹² Urban education thus reflected the rise of Enlightenment ideals and a growing interest in utilitarian knowledge. While still limited in access, these institutions began to lay the groundwork for the diversification of American education in the post-colonial period.

The regional variations in colonial American education created a fragmented but evolving system shaped by local priorities and constraints. New England’s communal literacy model contrasted with the elite privatism of the South, while the Middle Colonies balanced cultural pluralism with voluntary educational efforts. These differences were not merely geographic but ideological, reflecting divergent views on religion, class, gender, and the role of education in society.¹³ This diversity would later complicate efforts to establish a national system of public education, but it also reflected the dynamic and localized nature of colonial American life. The legacy of these regional disparities continues to inform debates about educational equity and local control in the United States to this day.

Gender and Education

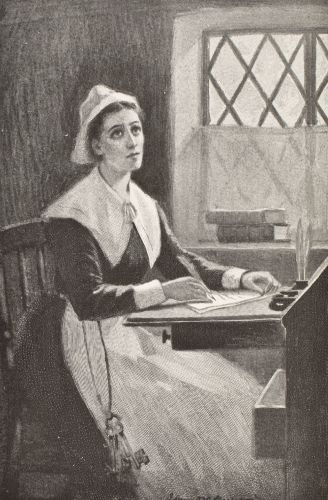

Education in colonial America was deeply shaped by prevailing gender norms that relegated women and girls to a subordinate social and intellectual status. Formal schooling for girls was rare in the 17th and early 18th centuries, especially beyond the primary level. Most educational opportunities available to females were informal and took place within the home, focusing on domestic skills rather than intellectual pursuits. In New England, where literacy was highly valued for religious reasons, some girls were taught to read the Bible, but writing, Latin, and higher education were considered inappropriate or unnecessary for women.¹⁴ The assumption that women had no need for formal schooling outside their roles as wives, mothers, and moral guardians reflected broader patriarchal structures that permeated colonial life. Educational inequality was not merely a reflection of access, but of ideology—women were considered intellectually inferior and thus unworthy of the same educational investment as men.¹⁵

Nevertheless, regional and religious differences created some variation in the educational experiences of women. Quakers in the Middle Colonies, particularly in Pennsylvania, were notable for promoting education for girls as well as boys. Their belief in spiritual equality before God translated into broader educational access, and some Quaker schools were coeducational.¹⁶ In New England, a few girls attended “dame schools,” informal neighborhood schools run by women that taught reading, basic arithmetic, and moral instruction. Yet these schools seldom prepared girls for anything beyond their expected domestic and religious roles.¹⁷ In the Southern colonies, opportunities for girls were even more limited, confined largely to the wealthier planter class, and often delivered by private tutors within the home. Female education, when it existed, was not aimed at intellectual development but at producing refined, obedient wives who could manage households and raise Christian children.¹⁸

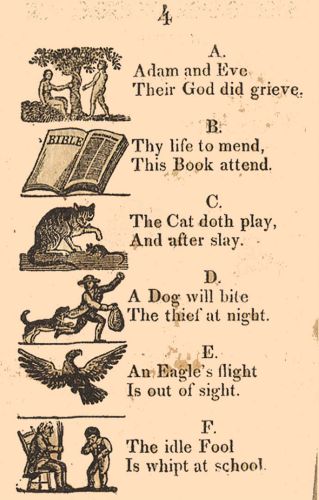

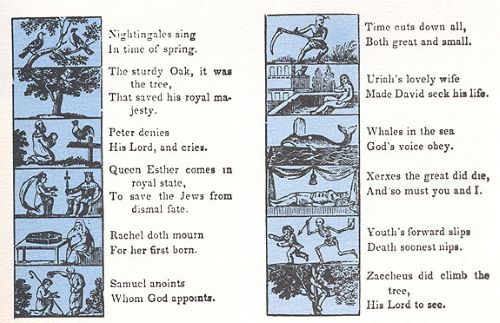

One of the key mechanisms through which gendered education was reinforced was curriculum. Boys were taught Latin, classical literature, logic, and rhetoric—subjects that prepared them for public life, leadership, or the ministry. In contrast, girls, when educated at all, were trained in sewing, etiquette, and religious piety.¹⁹ Educational materials such as primers and conduct books also reinforced strict gender roles. For instance, The New England Primer included verses and catechisms that emphasized obedience and virtue, especially for girls.²⁰ Even when girls became literate, the types of texts they were encouraged to read were limited to religious or moralistic literature, reinforcing their subordinate place within the intellectual hierarchy of the colonial world.

Despite these constraints, some women managed to achieve a degree of intellectual influence through informal or autodidactic means. Anne Bradstreet, for example, was educated in England before migrating to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and her poetry reflected a deep engagement with classical and religious themes.²¹ Similarly, women like Sarah Osborn and Esther Edwards Burr kept journals and correspondence that demonstrated thoughtful engagement with theology, philosophy, and public life, even if they were excluded from formal institutions.²² These women were exceptional, and their literacy and intellectual output were often tolerated only because they did not directly challenge the patriarchal status quo. Still, their writings suggest that education, even in limited forms, could empower women to participate in intellectual discourse, albeit within tightly regulated boundaries.

Gendered access to education in colonial America reinforced broader social hierarchies and preserved the patriarchal order. While male education was public, institutionalized, and designed for leadership and civic participation, female education—when it occurred—was private, domestic, and designed to uphold religious and moral norms.²³ These educational disparities laid the groundwork for persistent gender inequality in American schooling systems well into the 19th century. The seeds of change, however, were sown during the colonial period in the quiet resistance of literate women who found ways to educate themselves and pass on knowledge to others. These early instances of female intellectual engagement would later provide a foundation for the women’s education reform movements in the early Republic.

Education and Religion

Religion was the primary driver of education in colonial America, especially in the New England colonies, where the Puritan legacy left a profound imprint on educational values and institutions. The Puritans believed that literacy was essential for reading the Bible and ensuring both personal salvation and communal moral order. Their view of education was inseparable from their religious convictions, and this is reflected in early legislation like the Massachusetts School Laws of 1642 and 1647, which required towns to establish schools to ensure children could read the Scriptures.²⁴ These laws were not secular in motivation but were explicitly tied to the maintenance of a godly community. Ministers often served as schoolmasters, and religious catechisms formed the core of instructional materials.²⁵ As a result, literacy rates in Puritan New England were significantly higher than in other regions, largely due to the religious imperative for every individual to engage with the Bible.

In the Middle Colonies, religious diversity fostered a more pluralistic educational landscape. Quakers, Lutherans, Reformed Protestants, Catholics, and Jews all established their own schools, each reflecting distinct theological traditions and pedagogical approaches.²⁶ The Quakers were particularly notable for their emphasis on equality, including the education of girls and marginalized populations. Their schools combined spiritual instruction with practical knowledge, reflecting the Quaker ideal of inner light and moral conscience.²⁷ German-speaking communities often maintained bilingual schools where religious instruction was conducted in German, preserving both language and faith. Unlike New England’s relatively homogenous educational framework, the Middle Colonies saw competition and cooperation among different denominations, producing a varied and decentralized educational system tied to specific religious communities.

In the Southern Colonies, the Anglican Church was established by law, but its influence on education was less pronounced and more fragmented. The Church of England did not aggressively promote mass literacy or school-building in the colonies, partly due to the vast distances between settlements and the emphasis on plantation agriculture over civic infrastructure.²⁸ However, some religious initiatives did take root, such as the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG), which sought to provide religious instruction and basic education to both white settlers and enslaved Africans.²⁹ These efforts, though noble in intent, often failed to reach the broader population and were limited in scale. In contrast to the Puritan emphasis on universal literacy, the Southern colonies lacked a religiously motivated educational mandate, and formal schooling remained largely a private affair for the elite.

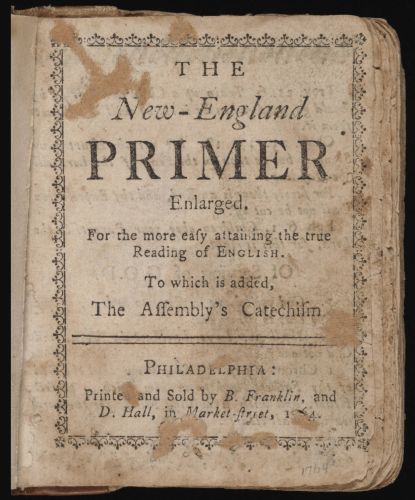

Religious content was embedded in almost all educational materials used in the colonies, regardless of region. The New England Primer, first published in the late seventeenth century, was the most widely used textbook and combined basic literacy instruction with heavy doses of Calvinist theology.³⁰ Children memorized Bible verses, catechisms, and moral aphorisms, shaping both their intellect and their spiritual development. Even when secular subjects like arithmetic or geography were taught, they were framed within a providential worldview.³¹ Schooling was thus a form of religious formation, reinforcing the broader goals of colonial churches in creating obedient, pious citizens. The intertwining of church and school in colonial life reflected a theocratic impulse that blurred the line between civic and sacred instruction.

Though education in colonial America was deeply influenced by religion, it also laid the groundwork for the eventual diversification and secularization of American schooling. As Enlightenment ideas began to take root in the late colonial period, some educational reformers—such as Benjamin Franklin—began to advocate for curricula that incorporated science, philosophy, and civic responsibility alongside or even in place of theological instruction.³² Nevertheless, the colonial period established a precedent for religious institutions shaping educational policy and content, a legacy that would persist well into the nineteenth century. The foundational role of religion in education during this era reveals not only the priorities of colonial societies but also the roots of enduring debates about the role of faith in American public education.

The Rise of Academies and Higher Education

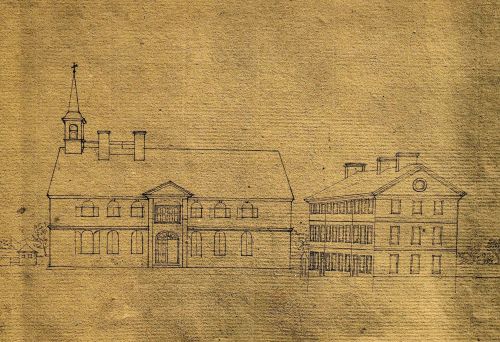

The development of higher education in colonial America was both a response to religious imperatives and a reflection of broader social and intellectual transformations. Initially, colleges were established primarily to train ministers and preserve the theological orthodoxy of particular denominations. Harvard College, founded in 1636 by the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay Colony, was the first institution of higher learning in British North America and served as a model for other colonial colleges.³³ Its curriculum was steeped in classical languages, logic, and divinity, and its primary purpose was the preparation of a learned clergy. Yale College followed in 1701, created by conservative Congregationalists who believed Harvard had become too liberal in its theological leanings.³⁴ These early colleges were small, elite institutions with limited student populations, but they played a foundational role in shaping intellectual and moral leadership in the colonies.

By the mid-eighteenth century, however, a growing demand for more practical and inclusive education led to the rise of academies, institutions that stood between the elementary schools and the traditional colleges. Benjamin Franklin was a leading proponent of this movement, famously founding the Academy of Philadelphia in 1751, which later became the University of Pennsylvania.³⁵ Franklin’s vision for the academy differed sharply from the narrow theological focus of Harvard and Yale. He advocated for a curriculum that included modern languages, science, history, and practical subjects like accounting and navigation—training that would be useful for commerce, civil service, and broader intellectual inquiry.³⁶ These academies were often nonsectarian or pluralistic in their religious affiliations and drew students from a wider social range, reflecting Enlightenment ideals and the increasing complexity of colonial society.

Other colonies followed suit, and by the eve of the American Revolution, nine colleges had been founded: Harvard, Yale, William and Mary, Princeton, Columbia (King’s College), Brown, Rutgers (Queen’s College), Dartmouth, and the College of Philadelphia. Each institution had distinct denominational roots—Anglican, Congregationalist, Presbyterian, Baptist, or Dutch Reformed—but all shared a commitment to producing educated men who could serve the church, the state, and the emerging professions.³⁷ The College of William and Mary, founded in Virginia in 1693, was the first institution in the South and trained Anglican ministers and colonial administrators.³⁸ Princeton (founded in 1746 as the College of New Jersey) became a center for Presbyterian theology and later played a crucial role in the intellectual ferment of the Revolution. These colleges gradually broadened their curricula to include rhetoric, mathematics, moral philosophy, and natural science, integrating religious instruction with humanist and Enlightenment thought.

The rise of academies and colleges also reflected and reinforced emerging class distinctions in colonial society. Access to higher education remained largely limited to white males from wealthy or prominent families. Admission often required proficiency in Latin and Greek, typically acquired through private tutors or elite preparatory schools.³⁹ Although a few institutions began experimenting with scholarships or opening enrollment to students from less affluent backgrounds, higher education still functioned as a gatekeeping mechanism that shaped the colonial elite. Moreover, these institutions excluded women entirely and often either marginalized or ignored the education of enslaved or Indigenous peoples.⁴⁰ Nevertheless, the formation of colleges and academies represented a significant evolution in the colonial intellectual landscape, offering new models of education that moved beyond mere catechetical instruction toward civic and professional preparation.

By the close of the colonial period, the groundwork for an American system of higher education had been laid, combining European classical traditions with local religious and civic needs. These institutions would evolve dramatically in the nineteenth century, expanding access and secularizing their missions, but their colonial origins reveal deep connections between education, religion, and power.⁴¹ The emergence of academies and colleges not only met immediate colonial needs for ministers and civic leaders but also established enduring institutions that would shape American intellectual and political life for generations. In the tensions between classical and practical education, between religious orthodoxy and Enlightenment innovation, colonial higher education reflected the broader cultural crossroads of a society on the brink of revolution.

Education after the American Revolution

The American Revolution had a profound impact on the educational landscape of the newly independent United States. The ideals of republicanism and civic virtue placed renewed emphasis on education as a means of cultivating informed and virtuous citizens. Leaders such as Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Rush believed that the survival of the republic depended on the education of its citizenry.⁴² Jefferson, in particular, was a staunch advocate of public education, proposing systems of tax-supported schools and arguing that a literate electorate was essential to democratic governance.⁴³ While many of his proposals were not fully implemented in his lifetime, they laid the intellectual foundation for future educational reforms. In this era, education began to be viewed less as a privilege reserved for the elite and more as a public good essential for the functioning of a republican society.

The post-Revolutionary period also saw an increase in the number and diversity of schools across the states. While earlier colonial education had been dominated by church-affiliated institutions, post-revolutionary America saw the gradual growth of secular and state-sponsored schools.⁴⁴ Academies proliferated, many of them founded by private benefactors or community groups. These academies, which offered secondary education, became popular alternatives to traditional Latin grammar schools. They included a broader curriculum that emphasized not only classical studies but also mathematics, science, and modern languages.⁴⁵ The expansion of academies was part of a broader democratization of education, though disparities in access remained significant, especially along lines of class, race, and gender.

Women’s education also experienced a notable shift after the Revolution. The rise of the ideology of “Republican Motherhood” posited that women, as mothers of future citizens, needed to be educated in order to instill civic virtue in their children.⁴⁶ This justification opened new avenues for female education, leading to the establishment of female academies and seminaries throughout the early republic. While these institutions generally did not offer the same level of instruction as those for men, they did provide more rigorous academic training than had been available to women previously. Prominent educators like Emma Willard and Catharine Beecher championed female education, advocating not just for women’s domestic roles but for their intellectual development.⁴⁷ These changes marked a crucial step in the long evolution toward educational equity in the United States.

Another development in the post-Revolutionary period was the slow emergence of state education systems. While educational policy remained largely decentralized, several states began to formalize their school systems through legislation. Massachusetts led the way with reforms in the 1780s and 1790s that sought to standardize school funding and teacher qualifications.⁴⁸ These reforms were inspired in part by Enlightenment ideals and a desire to institutionalize the values of the Revolution. However, progress was uneven, and many rural areas continued to rely on informal schooling or local subscription schools. Nonetheless, the concept of education as a state responsibility had begun to take hold, setting the stage for the common school movement of the nineteenth century.

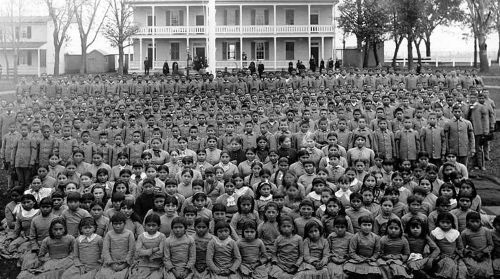

Despite these advances, significant limitations persisted. African Americans, both free and enslaved, were largely excluded from formal education, particularly in the South, where laws often prohibited teaching enslaved people to read.⁴⁹ Native American education remained focused on assimilation through missionary efforts and boarding schools, continuing patterns established in the colonial period. Furthermore, the absence of a national educational policy meant that regional and local disparities continued to shape educational opportunities. Even so, the period following the Revolution witnessed a broadening of educational ideals and institutions. The Revolution had altered not just the political order, but also the educational vision of the new nation, sowing the seeds for the democratization of learning in the decades to come.

Conclusion

The education of children in early America was a reflection of its social, religious, and economic contexts. From Puritan New England’s focus on literacy and moral instruction to the aristocratic private tutoring of Southern elites, education was far from uniform. Gender roles and regional differences further complicated the educational landscape. Nonetheless, these early efforts laid important groundwork for the evolution of the American educational system, influencing the development of public schooling and the eventual expansion of educational opportunities to broader segments of the population.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Lawrence A. Cremin, American Education: The Colonial Experience, 1607–1783 (New York: Harper & Row, 1970), 129.

- Bernard Bailyn, Education in the Forming of American Society (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1960), 78–79.

- Carl F. Kaestle, Pillars of the Republic: Common Schools and American Society, 1780–1860 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983), 12–14.

- Gary B. Nash, Quakers and Politics: Pennsylvania, 1681–1726 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968), 93–94.

- Frederick Rudolph, The American College and University: A History (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990), 19–21.

- Cremin, 121–23.

- Kaestle, 9–11.

- Bailyn, 63–66.

- Richard Hofstadter, America at 1750: A Social Portrait (New York: Knopf, 1971), 164–65.

- Gary B. Nash, 107–08.

- Jon Butler, Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990), 134.

- Rudolph, 24–26.

- Colin G. Calloway, The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 203.

- Ruth Wallis Herndon and John E. Murray, Children Bound to Labor: The Pauper Apprentice System in Early America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009), 45.

- Nancy F. Cott, The Bonds of Womanhood: “Woman’s Sphere” in New England, 1780–1835 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977), 19–21.

- Gary B. Nash, 111.

- E. Jennifer Monaghan, Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005), 93–94.

- Hofstadter, 169–70.

- Bailyn, 82–84.

- Monaghan, 121.

- Wendy Martin, An American Triptych: Anne Bradstreet, Emily Dickinson, Adrienne Rich (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 25–28.

- Laurie Crumpacker, “Women and Literacy in Colonial New England,” Early American Studies 5, no. 1 (2007): 103–05.

- Mary Kelley, Learning to Stand and Speak: Women, Education, and Public Life in America’s Republic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 12.

- Cremin, 130–32.

- Bailyn, 36–38.

- Butler, 115.

- Gary B. Nash, 107–09.

- Hofstadter, 167–69.

- Rhys Isaac, The Transformation of Virginia, 1740–1790 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982), 114–15.

- Monaghan, 87–89.

- Margaret A. Nash, Women’s Education in the United States, 1780–1840 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 17.

- Rudolph, 24.

- Samuel Eliot Morison, The Founding of Harvard College (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1935), 3–5.

- George M. Marsden, The Soul of the American University: From Protestant Establishment to Established Nonbelief (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 23.

- Benjamin Franklin, Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania (Philadelphia, 1749), 1–4.

- Thomas Woody, A History of Women’s Education in the United States, vol. 1 (Lancaster: Science Press, 1929), 91.

- Rudolph, 13–15.

- Herbert B. Adams, Thomas Jefferson and the University of Virginia (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1888), 18–20.

- Cremin, 239.

- Craig Steven Wilder, Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2013), 54–57.

- Jurgen Herbst, From Religion to Politics: Debates and Conflicts in American Higher Education (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996), 27–30.

- Kaestle, 5–7.

- Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, ed. William Peden (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955), 147–48.

- Cremin, 25–27.

- Nancy Beadie, Education and the Creation of Capital in the Early American Republic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 49–52.

- Linda K. Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980), 283–85.

- Margaret A. Nash, 58–62.

- Edward J. Power, A Legacy of Learning: A History of Western Education (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991), 239.

- James D. Anderson, The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 6–9.

Bibliography

- Adams, Herbert B. Thomas Jefferson and the University of Virginia. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1888.

- Anderson, James D. The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988.

- Bailyn, Bernard. Education in the Forming of American Society. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1960.

- Beadie, Nancy. Education and the Creation of Capital in the Early American Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Butler, Jon. Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990.

- Calloway, Colin G. The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Cott, Nancy F. The Bonds of Womanhood: “Woman’s Sphere” in New England, 1780–1835. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977.

- Cremin, Lawrence A. American Education: The Colonial Experience, 1607–1783. New York: Harper & Row, 1970.

- Crumpacker, Laurie. “Women and Literacy in Colonial New England.” Early American Studies 5, no. 1 (2007): 99–122.

- Franklin, Benjamin. Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania. Philadelphia, 1749.

- Herbst, Jurgen. From Religion to Politics: Debates and Conflicts in American Higher Education. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996.

- Herndon, Ruth Wallis, and John E. Murray. Children Bound to Labor: The Pauper Apprentice System in Early America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009.

- Hofstadter, Richard. America at 1750: A Social Portrait. New York: Knopf, 1971.

- Isaac, Rhys. The Transformation of Virginia, 1740–1790. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982.

- Jefferson, Thomas. Notes on the State of Virginia. Edited by William Peden. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955.

- Kaestle, Carl F. Pillars of the Republic: Common Schools and American Society, 1780–1860. New York: Hill and Wang, 1983.

- Kelley, Mary. Learning to Stand and Speak: Women, Education, and Public Life in America’s Republic. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- Kerber, Linda K. Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980.

- Marsden, George M. The Soul of the American University: From Protestant Establishment to Established Nonbelief. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Martin, Wendy. An American Triptych: Anne Bradstreet, Emily Dickinson, Adrienne Rich. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984.

- Monaghan, E. Jennifer. Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Founding of Harvard College. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1935.

- Nash, Gary B. Quakers and Politics: Pennsylvania, 1681–1726. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

- Nash, Margaret A. Women’s Education in the United States, 1780–1840. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

- Power, Edward J. A Legacy of Learning: A History of Western Education. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991.

- Rudolph, Frederick. The American College and University: A History. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990.

- Wilder, Craig Steven. Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2013. Woody, Thomas. A History of Women’s Education in the United States. Vol. 1. Lancaster: Science Press, 1929.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.23.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.