The history of nineteenth century pandemics reveals how deeply infectious disease shaped the development of modern public health.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Pandemics shaped the political and social landscape of the nineteenth century with a force that few other historical phenomena could match. Cholera alone swept the world in a series of pandemics beginning in 1817, spreading from Bengal into the Middle East, Russia, and finally Europe and North America between 1829 and 1837.¹ These outbreaks unfolded during an era when most governments still interpreted disease through miasma theory, the belief that illness spread through noxious atmospheric vapors rather than through identifiable pathogens.2 Because scientific understanding remained limited, state interventions relied heavily on quarantine regulations, sanitary policing, and the expansion of public health boards, each of which reflected local political pressures and cultural expectations rather than consistent epidemiological evidence.3

Communities faced these crises with a mixture of fear, improvisation, cooperation, and resistance. Smallpox vaccination campaigns spread across Europe after Edward Jenner’s findings became widely adopted, yet compulsory vaccination laws generated opposition in cities such as Leicester, where antivaccination demonstrations became a central feature of local politics beginning in the 1850s.4 Religious organizations, immigrant associations, and mutual aid societies played decisive roles during cholera and yellow fever outbreaks, particularly in cities such as New Orleans and Memphis where municipal services collapsed under the strain of repeated epidemics.5 These local responses often emerged from necessity rather than ideology, as communities filled gaps left by governments that struggled to respond effectively.

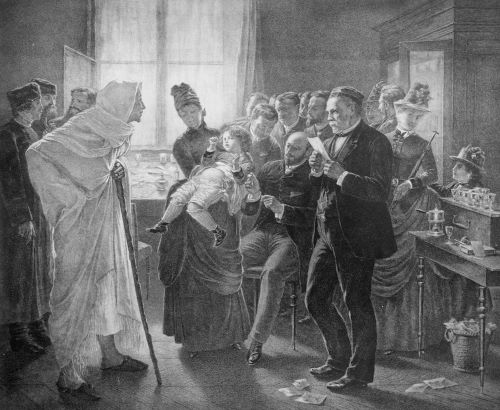

By the late nineteenth century, scientific breakthroughs began transforming the foundations of public health. John Snow’s investigation of the 1854 cholera outbreak in London used spatial analysis to challenge miasma theory and support a waterborne model of transmission.6 Louis Pasteur’s experiments in the 1860s and 1870s further demonstrated the microbial nature of infectious disease, while Robert Koch’s identification of the tubercle bacillus in 1882 provided laboratory confirmation that specific pathogens caused distinct illnesses.7 These developments allowed governments to experiment with new policies, although public health reform progressed unevenly across different regions and political systems.

The nineteenth century therefore stands as a period defined by both continuity and transformation in pandemic response. States clung to older theories even as new scientific evidence accumulated, and communities navigated crises through informal networks, protest, and cooperation. As a result, the century became an incubator for modern public health practice, shaping the institutions and scientific assumptions that governed epidemic response in the twentieth century.8

The First Cholera Pandemic (1817–1824): Globalization and Early State Responses

The first cholera pandemic began in Bengal in 1817, spreading outward from the Ganges Delta during a period of expanding commercial and military networks under British colonial rule.9 Contemporary observers noted the rapidity with which the disease moved along trade and pilgrimage routes, affecting Calcutta, Bombay, and other key port cities before reaching Southeast Asia and the Middle East.10 The East India Company attempted rudimentary containment through local quarantine stations and the regulation of troop movement, yet the colonial government lacked both scientific understanding and administrative coordination to impose consistent policy.11

As cholera extended westward, the Russian Empire faced growing pressure to respond to rising mortality in its southern provinces. The disease reached Astrakhan by 1823 and continued its march into the Volga basin, prompting the establishment of military cordons intended to restrict population movement between affected districts.12 Russian officials also issued public health advisories and sought to improve urban cleanliness, although these measures depended heavily on local enforcement and often conflicted with the practical realities of trade, agriculture, and regional mobility.13

Other regions confronted the pandemic through their own institutional frameworks. The Ottoman authorities implemented quarantine procedures in ports such as Basra and Trabzon, drawing on existing models for managing plague outbreaks.14 Maritime quarantines also appeared in the Persian Gulf and throughout parts of Southeast Asia. These responses reflected an older, pre-bacteriological system that emphasized control of movement and environmental regulation rather than identification of specific agents of disease.15

Communities across Asia reacted to cholera with a mix of apprehension and adaptation. In many areas, local healers and religious leaders offered explanatory frameworks rooted in spiritual or cosmological interpretations of illness.16 Pilgrimage centers such as Mecca faced recurrent threats because of dense seasonal population influxes, leading to the eventual introduction of quarantine regulations at the Red Sea ports by local authorities responding to both internal pressure and international diplomatic demands.17 Despite these interventions, the absence of coherent scientific understanding ensured that community-level coping strategies varied significantly across regions.

The first cholera pandemic thus revealed the limits of early nineteenth-century state capacity to manage fast-moving infectious disease. Governments relied on traditional public health tools such as quarantines and cordons, while communities mobilized through religious, charitable, or informal networks to confront mortality on a scale without recent precedent. The experience exposed the need for more coordinated transregional policies and highlighted the growing interdependence of global populations in an age of expanding imperial and commercial contact.18

The Second Cholera Pandemic (1829–1837): Europe and North America Confront a New Threat

Cholera reentered the historical stage in 1829 when new outbreaks emerged in Central Asia and moved rapidly into the Russian Empire, reaching Orenburg, Moscow, and Saint Petersburg by 1831.19 Russian authorities implemented large scale quarantines, military patrols, and movement restrictions in an effort to contain the disease, but these measures provoked intense public resistance. Riots in Saint Petersburg and other cities reflected widespread suspicion that physicians and officials were poisoning the sick or using hospitals to conceal deaths.20 These events revealed deep fractures between state authority and popular trust during epidemic crisis.

By 1831 cholera had crossed into Poland, Prussia, Austria, and the rest of Central Europe, prompting governments to adopt a range of public health measures. Prussian officials revived sanitary regulations first formalized during plague outbreaks, while Austrian authorities deployed local health commissions to monitor travelers, enforce quarantines, and regulate burial practices.21 French administrators oscillated between strict quarantine enforcement and more moderate approaches shaped by mercantile pressures, since prolonged sanitary cordons threatened trade.22 These variations exposed significant differences in how European governments balanced economic interests with epidemic control.

Britain confronted cholera in 1831 and 1832, particularly in London, Sunderland, and Glasgow, where outbreaks produced widespread fear and political agitation. Local Boards of Health were established to oversee sanitation, inspect housing, and manage burial grounds.23 Nonetheless, the British public responded with skepticism, partly because many medical authorities continued to support miasma theory and rejected the possibility of person to person transmission.24 Anti-quarantine protests erupted in several cities, reflecting anxieties about state intrusion, economic disruption, and unequal treatment of the poor.25 These reactions demonstrated how epidemic measures often amplified existing political tensions, particularly in industrializing urban centers.

The pandemic reached North America in 1832 when infected passengers disembarked in Quebec, allowing the disease to travel along the St. Lawrence River into Montreal and cities in the United States. New York and Philadelphia responded by creating temporary Boards of Health that ordered street cleaning, fumigation, and the removal of refuse.26 Yet cholera also intensified xenophobia, especially against Irish immigrants who were blamed for importing the disease.27 Charitable organizations, particularly Catholic benevolent societies, provided care when municipal systems failed, demonstrating the central role of voluntary institutions in nineteenth century urban health.28

Despite regional variations, the second cholera pandemic exposed shared patterns across Europe and North America. State interventions remained shaped by miasma theory, commercial interests, and political pressures, while communities mobilized through charity, religious leadership, and protest. The pandemic underscored the fragility of early nineteenth century public health structures and highlighted the need for more coordinated and scientifically grounded responses, a lesson that would gain urgency as subsequent cholera waves struck later in the century.29

Cholera in the United States: Urban Sanitation, Immigration Panic, and Social Division

Cholera arrived in the United States during the 1832 wave when an infected vessel reached Quebec and the disease traveled southward into New York and Philadelphia.30 Municipal governments responded by forming emergency Boards of Health that imposed street cleaning mandates, refuse removal programs, and temporary quarantine procedures. These measures reflected the continued dominance of miasma theory, which led officials to prioritize environmental reforms over direct interventions in person to person transmission.31

Urban demographic changes deeply shaped the American experience of cholera. Irish immigrants bore much of the public blame during the 1832 and 1849 outbreaks, especially in New York, where nativist newspapers and political groups portrayed immigrant neighborhoods as sources of contagion.32 This fusion of disease rhetoric with anti-immigrant prejudice fed into wider nativist movements that crystallized in the 1850s and helped define the politics of the Know Nothings and related organizations.33 Cholera therefore became part of a broader struggle over belonging, citizenship, and urban space.34

Local community organizations often stepped in where municipal capacity failed. Catholic benevolent societies, mutual aid groups, and volunteer nurses provided care for the sick when hospitals were overwhelmed or inaccessible to the poor.35 In cities such as New York and Cincinnati, parish-based charities organized food, nursing, and burial support for immigrant families, creating informal safety nets that operated alongside or in place of official services.36 These efforts showed how working-class and immigrant communities relied on their own institutions to survive crises that municipal governments struggled to manage.37

Governmental strategies evolved across successive epidemics. During the 1849 outbreak, New York’s Board of Health expanded inspection districts, regulated privies and tenements, and began to collect more systematic mortality data. The 1866 cholera wave pushed the city toward more durable sanitary reform and contributed to the establishment of the Metropolitan Board of Health, often described as the first lasting public health authority in the United States.38 Although these developments did not resolve the structural inequalities that shaped exposure to disease, they marked a shift toward more bureaucratized, professional public health administration at the municipal level.39

The American response to cholera therefore exposed the entanglement of epidemic disease with immigration, class, and the politics of urban governance. Environmental measures rooted in miasma theory coexisted with patterns of scapegoating and exclusion, while communities constructed their own systems of care to fill gaps in official provision. Over time, the recurring shocks of cholera helped to push city governments toward more permanent sanitary institutions, even as deep social divisions persisted.40

The Yellow Fever Epidemics: New Orleans, Memphis, and the Limits of Nineteenth Century Public Health

Yellow fever remained one of the most feared diseases in the nineteenth century, especially in port cities along the Gulf Coast where the climate supported recurring outbreaks. New Orleans suffered one of the worst epidemics in its history in 1853 when more than eight thousand residents died in a period of only a few months.41 Medical authorities could not identify a mode of transmission, and municipal leaders turned to environmental explanations that fit prevailing miasma assumptions. Despite city efforts to improve drainage and remove refuse, the disease spread faster than public health services could respond.

Local communities developed their own informal systems of relief. Religious orders, benevolent societies, and neighborhood associations provided care for the sick and burial support for grieving families when official institutions collapsed under the scale of mortality.42 These organizations operated outside the capacity of municipal government, revealing how much epidemic survival rested on community infrastructure rather than state intervention.

Memphis experienced repeated yellow fever epidemics during the nineteenth century, culminating in the catastrophic outbreak of 1878. The disease killed thousands and drove much of the population to flee, leaving the city effectively without functioning government. The Howard Association, a volunteer relief group, organized nurses, distributed supplies, and coordinated care when official structures ceased to operate.43 The severity of the crisis prompted national debate about federal responsibility for epidemic management.

Yellow fever also exposed entrenched racial and class inequalities. Wealthy residents often escaped outbreaks by leaving the city, while poor communities and Black residents faced greater exposure and fewer medical resources. Claims about racial immunity circulated widely, even though they lacked scientific validity and reflected the broader social hierarchies of the American South. These disparities shaped both the burden of disease and the public discourse surrounding yellow fever.44

Although the cause of yellow fever remained unknown until the turn of the twentieth century, recurring epidemics encouraged new thinking about urban sanitation and public health organization. Municipal leaders debated drainage, water supply, garbage removal, and the creation of more permanent health authorities. These initiatives did not prevent yellow fever but contributed to the broader evolution of urban health policy in the United States. The cumulative experience of these epidemics demonstrated the limits of nineteenth century public health while also laying the groundwork for more systematic approaches in the decades that followed.45

Smallpox Resurgence and the Rise of Vaccination Controversies

Smallpox persisted throughout the nineteenth century as one of the most lethal infectious diseases, erupting in periodic outbreaks across Europe and North America despite widespread acceptance of vaccination. Britain experienced a notable resurgence in the 1830s and 1840s, prompting Parliament to pass the Vaccination Act of 1853, which required infant vaccination.46 These laws reflected growing administrative confidence in state managed preventive health, even as scientific understanding of viral disease remained limited. Enforcement, however, varied dramatically among local authorities, and widespread dissatisfaction emerged as families resisted compulsory measures.

The expansion of vaccination mandates triggered the emergence of organized antivaccination activism. Leicester became the center of this movement in Britain, where thousands protested compulsory vaccination in 1885, arguing that the laws infringed on personal liberty and disproportionately targeted the poor.47 Critics also invoked concerns about contaminated lymph, unsafe techniques, and state coercion. Their activism influenced legislative reform, including the Vaccination Act of 1898, which introduced a “conscience clause” permitting exemptions for objecting parents. These developments showed how public health policy could be reshaped through sustained civic resistance.48

In the United States, vaccination campaigns followed a more decentralized pattern. Cities such as Boston and Philadelphia enforced periodic mandatory vaccination during outbreaks, while other regions relied on voluntary participation or school based requirements. Local Boards of Health conducted door to door vaccination during epidemics, and compliance often depended on neighborhood networks and community leaders rather than uniform state authority. The courts eventually upheld compulsory vaccination in Jacobson v. Massachusetts (1905), a case that emerged from nineteenth century debates about state power and individual liberty.49

Scientific and administrative disputes shaped the broader conversation surrounding smallpox. Officials disagreed about revaccination schedules, the purity of vaccine lymph, and the role of arm-to-arm techniques, which sometimes transmitted unrelated infections. Medical journals published conflicting claims about effectiveness, often influenced by local outbreak conditions, reporting accuracy, and changing standards of evidence. These debates revealed the complexity of implementing population wide vaccination at a time when virology did not yet exist as a discipline. The resulting uncertainty contributed to fluctuating public confidence in preventive medicine.50

Despite controversy, vaccination remained the primary defense against smallpox, and its impact became increasingly visible by the end of the nineteenth century. Mortality declined in regions with sustained vaccination programs, and civil registration systems provided more reliable data for assessing effectiveness. The political battles surrounding compulsory vaccination ultimately shaped modern public health law, strengthening state authority while acknowledging limits imposed by civic resistance and public sentiment. The experience of smallpox highlighted the tension between scientific claims, governmental power, and community autonomy during a transformative period in global health.51

The Third Pandemic of Bubonic Plague (1894–1900s): Germ Theory and Colonial Power

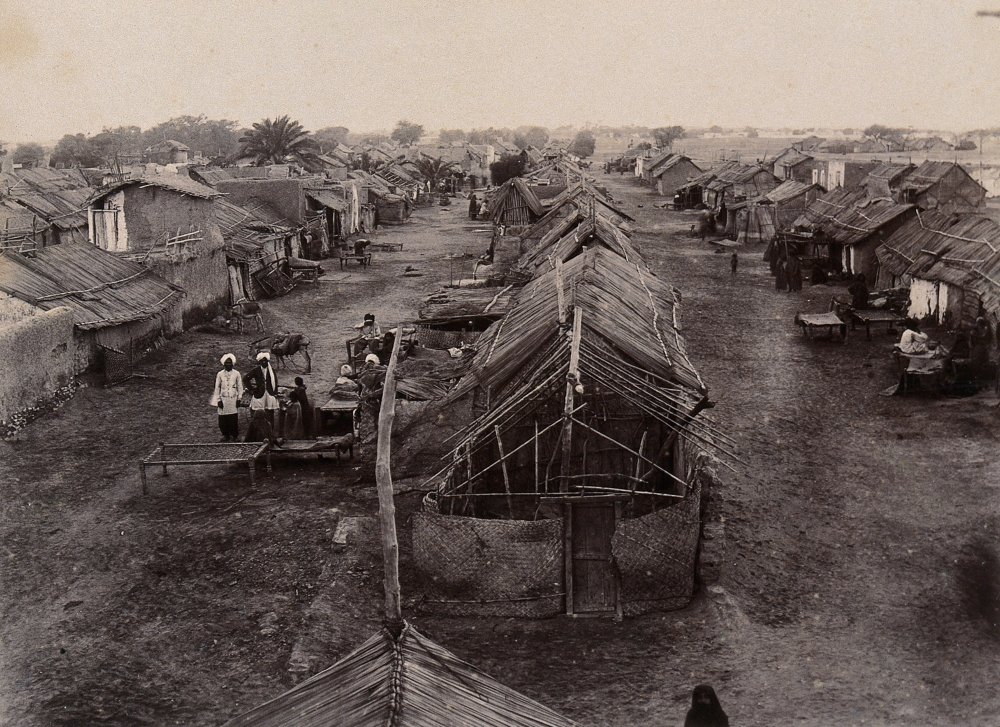

The third pandemic of bubonic plague began in the 1890s and quickly revealed how global trade, imperial governance, and scientific uncertainty intersected at the end of the nineteenth century. Outbreaks in Yunnan reached Hong Kong in 1894, where mortality was severe and the disease spread rapidly through overcrowded districts connected to maritime commerce.52 Public health officials faced an illness whose etiology remained in question, even though laboratory methods had advanced significantly during the preceding decades.

The Hong Kong outbreak became a turning point because it allowed scientists to apply new bacteriological techniques directly to an epidemic setting. Alexandre Yersin successfully identified the plague bacillus in 1894, using methods informed by Pasteurian laboratory practice, while Shibasaburo Kitasato conducted parallel investigations under the influence of Koch’s bacteriological tradition.53 Their findings provided one of the earliest clear demonstrations that a specific microorganism caused a major epidemic disease, and they contributed to the broader acceptance of germ theory among international medical authorities.

The pandemic spread rapidly along shipping routes, reaching India, where Bombay experienced major outbreaks beginning in 1896. British colonial officials implemented aggressive sanitary interventions, including forced inspections, house searches, and the isolation of suspected cases.54 These policies provoked intense resistance, particularly when they violated religious practice, disrupted family life, or threatened economic stability. Riots in Bombay and Poona highlighted how colonial public health actions could magnify political tensions and undermine cooperation during crisis.

Commercial centers across Asia, Africa, and the Pacific also experienced plague outbreaks during these years. Port cities such as Honolulu, Cape Town, and Sydney implemented quarantine measures, fumigation, and rat control, yet the success of these efforts varied widely depending on administrative capacity and public trust. Some measures relied heavily on race based segregation or assumptions about “native” susceptibility, reinforcing hierarchies already embedded in colonial governance. These dynamics shaped how communities experienced epidemic policy and influenced long term relationships between local populations and imperial authorities.55

The scientific advances generated during this pandemic transformed how governments and international organizations understood infectious disease. Evidence from Yersin’s work and subsequent research on vector transmission helped establish bacteriology as the dominant framework for epidemic response. These developments informed new international sanitary conventions and encouraged cooperation among states concerned about maritime spread. By the early twentieth century, plague had helped consolidate a global model of public health rooted in laboratory science, surveillance, and cross border coordination.56

Shifting Scientific Paradigms: From Miasma to Contagion to Germ Theory

The nineteenth century witnessed an extraordinary transformation in how disease was understood, debated, and investigated. Early in the century, most medical authorities accepted miasma theory, which held that diseases such as cholera and plague arose from atmospheric corruption or decaying organic matter. The dominance of this framework shaped sanitation reforms, quarantine policies, and even the architecture of cities. Yet recurring epidemics revealed gaps in the explanatory power of miasma doctrine, especially in crowded industrial regions where disease did not always follow predicted environmental patterns.

A crucial shift began with new empirical approaches to epidemic investigation. During the 1854 cholera outbreak in London, John Snow mapped cases around the Broad Street pump and argued that cholera was waterborne rather than airborne. His analysis challenged prevailing assumptions by linking disease transmission to a specific environmental source.57 William Farr, working within the General Register Office, collected extensive mortality data that further destabilized older theories, even though he initially interpreted these patterns within a miasmatic framework. Their combined work helped establish epidemiology as a distinct field grounded in systematic data collection and spatial analysis.58

Laboratory science expanded these insights in the second half of the century. Louis Pasteur’s experiments on fermentation and microorganisms in the 1860s offered compelling evidence that living agents, not spontaneous generation, caused many forms of disease.59 Robert Koch built upon this work by developing methods for isolating and identifying specific bacteria, culminating in his demonstration of the tubercle bacillus in 1882. These discoveries provided undeniable proof that microorganisms could produce distinct illnesses, and they reoriented medical research toward laboratory verification rather than theoretical debate.

As germ theory gained traction, public health officials revised their understanding of prevention, though policy change lagged behind scientific discovery. Many cities continued to implement sanitation programs rooted in older environmental assumptions, while gradually incorporating bacteriological insights into inspection regimes, isolation practices, and disinfection protocols. The coexistence of these models illustrated how scientific revolutions unfolded unevenly across regions, professions, and institutions. The transition from miasma to germ theory therefore marked not only a conceptual shift but also a gradual reorganization of public health authority.60

These developments also reshaped the relationship between science and the state. Governments increasingly relied on laboratory evidence to justify public health interventions, while medical professionals gained new influence as experts in bacteriology and epidemiology. International sanitary conferences convened during the late nineteenth century incorporated bacteriological findings into maritime quarantine rules and disease notification systems. By the century’s end, the foundations of modern infectious disease control had been laid, integrating statistical analysis, laboratory science, and administrative regulation.61

Community-Level Responses: Faith-Based Groups, Mutual Aid, and Informal Health Networks

Throughout the nineteenth century, communities developed their own strategies for managing epidemic disease, often functioning as the first line of response when governments faltered. In cities struck by cholera, yellow fever, or smallpox, religious institutions organized relief networks that provided nursing care, burial services, and food distribution. Catholic and Protestant congregations in New Orleans, Memphis, London, and Liverpool established visiting committees during outbreaks, reflecting deeply rooted traditions of charitable care. These initiatives operated independently of state authority and responded quickly to local needs, making them indispensable during periods of crisis.

Mutual aid societies also played an essential role in epidemic environments. Many of these organizations emerged from immigrant communities, fraternal orders, and ethnic associations that sought to support members during illness, unemployment, or bereavement. In the United States, Irish and German benevolent societies provided financial assistance and burial funds during cholera outbreaks, while African American organizations created informal nursing networks in cities where public hospitals excluded Black patients.62 Their work demonstrated how communities mobilized internal resources when structural inequalities limited access to formal medical systems.

Women’s voluntary efforts expanded in scope as epidemics intensified. Middle class women often staffed charity hospitals, organized home nursing, and coordinated relief drives, while working class women cared for neighbors in overcrowded housing districts. Volunteer nursing became especially visible during yellow fever epidemics in the American South and during cholera outbreaks in European industrial cities. These contributions were seldom recognized in official reports, yet they were crucial for communities that relied on care networks constructed outside the boundaries of professional medicine.

Community responses also operated through informal channels shaped by neighborhood networks, kinship ties, and local leadership. In many working class districts, residents relied on midwives, herbal practitioners, or experienced neighbors rather than physicians whose services were unaffordable or unavailable. These informal caregivers provided advice on isolation, sanitation, and home treatment, and their authority often proved more influential than official guidance. The durability of these networks revealed how local knowledge filled gaps left by contested or inconsistent government directives.63

In some areas, community resistance became a defining feature of epidemic response. Residents of European and Russian cities protested sanitation campaigns they viewed as intrusive or discriminatory, while communities in India and the Middle East challenged colonial health regulations that disrupted family life, religious practice, or economic survival. These acts of resistance were grounded not only in mistrust but also in coherent communal values that prioritized autonomy, cultural practices, and local forms of care.64 As a result, public health initiatives frequently depended on cooperation between officials and local leaders, whose authority shaped the success or failure of epidemic interventions.65

Government-Level Responses: Bureaucratization, Quarantine Systems, and International Agreements

Governments in the nineteenth century experimented with a wide range of public health strategies as epidemics accumulated across borders. Many states relied on traditional tools such as maritime quarantine, sanitary cordons, and traveler inspection, drawing on older models developed for plague management. These measures aimed to restrict movement across borders or between districts, yet their effectiveness varied widely depending on administrative capacity, political pressures, and economic stakes. In mercantile cities, strict quarantines risked disrupting trade, which led officials to alternate between rigorous enforcement and more flexible policies shaped by commercial priorities.66

The century also saw the rise of permanent public health bureaucracies. Britain established local Boards of Health during cholera outbreaks in the 1830s, and later reforms created more stable municipal sanitary authorities that oversaw drainage, waste removal, and street cleaning. In France, the Conseil Supérieur de Santé played a central role in coordinating epidemic response. Cities such as Hamburg, Vienna, and Paris expanded their inspection regimes and developed municipal laboratories to test water quality and investigate disease. These institutions contributed to a growing belief that public health should be a regular function of the modern state rather than an improvised response triggered only by crisis.

In the United States, the creation of the Metropolitan Board of Health in New York in 1866 marked an early step toward durable public health administration. The Board introduced systematic inspection procedures, managed urban sanitation, and advanced data collection on mortality patterns. Other cities followed, but the structure of American federalism complicated the development of national oversight. The devastating yellow fever epidemic of 1878 ultimately pushed Congress to create the National Board of Health, which represented an early attempt to coordinate epidemic control across state lines, although its authority remained limited.67

International cooperation also expanded during the nineteenth century as states confronted the global circulation of disease. The first International Sanitary Conference met in Paris in 1851 to harmonize quarantine procedures for cholera and plague. Delegates debated the proper balance between trade protection and epidemic control, and although immediate results were limited, these meetings established a framework for ongoing diplomatic engagement on public health matters. Subsequent conferences incorporated bacteriological discoveries and produced more detailed regulations for maritime inspection and disease notification.68

Despite growing bureaucratization, governmental responses remained uneven and deeply influenced by political conflict, economic pressure, and varying levels of scientific acceptance. Some governments prioritized centralized control, while others delegated authority to local officials or relied on voluntary compliance. The diversity of these approaches reflected the absence of a unified scientific consensus and the complexity of governing in rapidly changing urban and imperial environments. By the century’s end, however, a recognizable international public health system had begun to take shape, rooted in surveillance, quarantine, and cooperation across borders.69

Public Distrust, Protest, and the Politics of Pandemic Response

Epidemics in the nineteenth century routinely produced public distrust of government action, especially when authorities imposed measures that disrupted daily life or threatened economic stability. In several European cities, quarantine regulations triggered resistance because they restricted movement, interfered with trade, or forced residents into hospitals widely believed to be places of near-certain death. Crowded industrial neighborhoods often interpreted sanitary inspections as invasive or punitive, and officials responded unevenly to public concerns. These tensions revealed how fragile trust remained at a time when governments struggled to explain the causes of epidemic disease in ways that communities found credible.⁷⁰

Violent protest became particularly visible during cholera outbreaks. In Russia, rumors that doctors were poisoning patients or deliberately mishandling corpses sparked riots in St. Petersburg, Sevastopol, and Kharkov during the 1830s.71 Similar unrest occurred in Italian cities, where residents rejected the forced hospitalization of suspected cases and resisted burial regulations that separated families from their dead. These uprisings were not simply expressions of fear but reflected deeper frustrations with autocratic rule, poverty, and perceived abuses of authority. Cholera thus intensified broader social and political conflicts already embedded in nineteenth century urban life.

In Britain and parts of Germany, conflict centered not on riot but on organized political resistance. Working class communities often rejected medical officers’ authority, particularly when officials blamed disease on the habits, homes, or moral character of the poor. Residents challenged the assumption that sanitary reforms should be enforced unevenly, and many objected to compulsory hospitalization or disinfection orders. These debates were amplified in print culture, especially as newspapers and pamphleteers criticized the state’s expanding role in health regulation. The result was a highly public negotiation over the boundaries of state intervention during epidemic crisis.72

Public distrust also emerged around new technologies of surveillance and recordkeeping. As governments expanded mortality registration and introduced systematic inspection regimes, many residents viewed these practices with suspicion. Some feared that detailed reporting could lead to property condemnation or the forced relocation of families living in overcrowded districts. Others worried that medical officers wielded excessive power under sanitary laws. Communities negotiated these pressures through petitions, public meetings, and alliances with sympathetic local officials who helped mediate between state authority and neighborhood autonomy.73

Despite these conflicts, protests and resistance often forced governments to reconsider the design and implementation of epidemic measures. Officials modified quarantine procedures, scaled back intrusive inspections, or introduced appeals processes for mandated isolation. These adjustments reflected the reality that public health policy could not succeed without at least some degree of cooperation from affected communities. The politics of pandemic response therefore revealed a fundamental tension between administrative ambition and the lived experience of ordinary people navigating the hardships of epidemic disease.74

Long-Term Consequences: Modern Public Health Born from Nineteenth Century Crisis

The nineteenth century’s repeated epidemics reshaped the foundations of public health in lasting ways. As cholera, yellow fever, smallpox, and plague exposed the limits of local improvisation, governments across Europe, Asia, and the Americas began to recognize the need for more permanent administrative structures. The accumulation of crisis taught policymakers that epidemic management could not rely solely on temporary Boards of Health or ad hoc quarantine committees. Instead, sustained bureaucratic institutions became necessary to organize sanitation, coordinate medical care, and maintain surveillance systems that could respond more effectively to recurring outbreaks.

Epidemiology emerged as a distinct scientific discipline during this period. The work of John Snow, William Farr, and other early investigators established new methods of disease mapping, mortality analysis, and statistical interpretation. Snow’s cholera mapping and Farr’s extensive vital statistics program provided tools that allowed public health officials to visualize and quantify the movement of epidemic disease.75 Their approaches created the methodological backbone for modern epidemiological practice and demonstrated how data collection could guide policy in ways that older medical theories could not.

The rise of bacteriology further altered public health’s intellectual foundations. Discoveries made by Pasteur, Koch, Yersin, and their students created a new explanatory framework in which specific microorganisms could be linked to particular diseases. This shift encouraged governments to introduce targeted interventions such as isolation wards, laboratory testing, and disinfection protocols directed at identifiable pathogens. The success of these measures in controlling smallpox, plague, and diphtheria increased political support for scientific approaches to epidemic control and strengthened the authority of medical professionals within state institutions.76

International coordination became one of the century’s most significant developments. Repeated global outbreaks convinced governments that national measures alone were insufficient and that transnational cooperation was essential to prevent the spread of disease through shipping and migration. The International Sanitary Conferences gradually produced standardized maritime regulations, surveillance agreements, and shared definitions of epidemic disease. These agreements laid the groundwork for early twentieth century organizations such as the Office International d’Hygiène Publique and, ultimately, the World Health Organization.77

By the end of the nineteenth century, a recognizable modern public health system had taken shape. Municipal governments developed permanent sanitary departments, national states invested in laboratories and disease reporting systems, and international conventions harmonized epidemic regulations across borders. Although responses remained uneven and shaped by inequality, the century’s crises created a new framework for understanding and managing disease. The legacies of these transformations continued into the twentieth century, influencing how nations confronted influenza, polio, and other modern epidemics.78

Conclusion

The history of nineteenth century pandemics reveals how deeply infectious disease shaped the development of modern public health. Epidemics placed extraordinary pressure on governments that were still building administrative capacity, prompting states to experiment with quarantine rules, sanitary reforms, and eventually more permanent institutions. These efforts emerged unevenly, but they collectively marked a transition from improvised crisis management to structured systems of surveillance, inspection, and civic regulation.

Communities played an equally central role in navigating epidemic disease. Religious organizations, mutual aid societies, informal caregivers, and neighborhood networks provided essential care long before state systems became reliable. Their work demonstrated that epidemic response depended not only on administrative authority but also on the resilience of local institutions with deep roots in social life. In many cities, it was these community based networks rather than municipal agencies that sustained families through periods of mass mortality and civic disruption.79

Scientific transformations altered the landscape even more dramatically. Snow’s cholera mapping, Farr’s statistical work, and the discoveries of Pasteur, Koch, and other bacteriologists created a new conceptual framework for understanding disease. This shift allowed public health officials to link specific pathogens to particular illnesses and to design interventions with greater precision. The impact of laboratory research could be seen in improved outbreak management, new approaches to isolation and sanitation, and the growing authority of medical professionals within state institutions.80

International cooperation expanded as disease spread along global trade networks. Governments increasingly recognized that national policies were insufficient in a world where maritime travel and migration connected distant populations. The International Sanitary Conferences provided a diplomatic arena for negotiating shared standards for quarantine, maritime inspection, and disease reporting. These conferences marked the earliest stages of the global health system that would become more fully institutionalized in the twentieth century.81

Taken together, these developments reveal a century defined by both crisis and innovation. Governments learned to administer public health more systematically, communities improvised new forms of care and resistance, and scientific discoveries transformed the epistemology of disease. By 1900, these combined forces had reshaped the relationship between the state, science, and society, laying the foundation for modern approaches to epidemic control. The nineteenth century thus stands as a pivotal moment in the long history of how human beings confront the threats posed by infectious disease.82

Appendix

Footnotes

- Mark Harrison, Disease and the Modern World: 1500 to the Present (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004), 68–70; World Health Organization, “Cholera Fact Sheet,” updated 2024.

- Christopher Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 42–48.

- Richard J. Evans, Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years 1830–1910 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 19–36.

- Nadja Durbach, Bodily Matters: The Anti-Vaccination Movement in England, 1853–1907 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005), 23–27.

- John Duffy, Sword of Pestilence: The New Orleans Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1853 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1966), 112–132.

- Steven Johnson, The Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic (New York: Riverhead, 2006), 78–89.

- William Coleman, Yellow Fever in the North: The Methods of Early Epidemiology (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987), 145–150.

- Mark Harrison, Disease and the Modern World: 1500 to the Present (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004), 95–101.

- Mark Harrison, Disease and the Modern World: 1500 to the Present (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004), 69–71.

- David Arnold, Colonizing the Body: State Medicine and Epidemic Disease in Nineteenth-Century India (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 199–202.

- Harrison, Disease and the Modern World, 70–72.

- John P. Davis, “Cholera and the Russian Army, 1817–1825,” Slavic Review 25, no. 3 (1966): 433–448.

- Richard J. Evans, Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years 1830–1910 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 21–24.

- Nükhet Varlık, Plague and Empire in the Early Modern Mediterranean World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 301–305.

- Harrison, Disease and the Modern World, 72–74.

- Arnold, Colonizing the Body, 210–214.

- Michael Christopher Low, Imperial Mecca: Ottoman Arabia and the Indian Ocean Hajj (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020), 85–90.

- Harrison, Disease and the Modern World, 75–78.

- Christopher Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 51–54.

- Evans, Death in Hamburg, 24–28.

- Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice, 55–58.

- Alain Corbin, The Foul and the Fragrant: Odor and the French Social Imagination (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986), 128–134.

- Anne Hardy, The Epidemic Streets: Infectious Disease and the Rise of Preventive Medicine 1856–1900 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 13–17.

- Evans, Death in Hamburg, 32–36.

- Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice, 59–63.

- Charles E. Rosenberg, The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 12–18.

- Rosenberg, The Cholera Years, 20–25.

- John Duffy, A History of Public Health in New York City, 1625–1866 (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1968), 408–415.

- Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice, 63–66.

- Rosenberg, The Cholera Years, 12–18.

- Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice, 59–63.

- Rosenberg, The Cholera Years, 20–25.

- Tyler Anbinder, Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 45–49.

- Rosenberg, The Cholera Years, 26–30.

- Duffy, A History of Public Health in New York City, 1625–1866, 408–415.

- Duffy, A History of Public Health in New York City, 1625–1866, 410–411.

- John Duffy, The Sanitarians: A History of American Public Health (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990), 83–88.

- Duffy, The Sanitarians, 92–98.

- Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice, 66–70.

- Rosenberg, The Cholera Years, 72–80.

- Duffy, Sword of Pestilence, 23–25.

- Margaret Humphreys, Yellow Fever and the South (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 58–62.

- John H. Ellis, Yellow Fever and Public Health in the New South (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1992), 48–52.

- Humphreys, Yellow Fever and the South, 103–110.

- Ellis, Yellow Fever and Public Health in the New South, 115–122.

- Nadja Durbach, Bodily Matters: The Anti-Vaccination Movement in England, 1853–1907 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005), 18–22.

- Durbach, Bodily Matters, 39–46.

- Michael Worboys, Spreading Germs: Disease Theories and Medical Practice in Britain, 1865–1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 226–231.

- James Colgrove, State of Immunity: The Politics of Vaccination in Twentieth-Century America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 23–30.

- Worboys, Spreading Germs, 210–216.

- Duffy, The Sanitarians, 121–126.

- Carol Benedict, Bubonic Plague in Nineteenth-Century China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996), 84–89.

- Myron Echenberg, Plague Ports: The Global Urban Impact of Bubonic Plague, 1894–1901 (New York: New York University Press, 2007), 34–39.

- Benedict, Bubonic Plague in Nineteenth-Century China, 141–147.

- Echenberg, Plague Ports, 78–84.

- Echenberg, Plague Ports, 201–207.

- Steven Johnson, The Ghost Map, 78–89.

- Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice, 102–108.

- Gerald L. Geison, The Private Science of Louis Pasteur (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995), 56–63.

- Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice, 119–123.

- Hardy, The Epidemic Streets, 203–210.

- Duffy, A History of Public Health in New York City, 1625–1866, 410–415.

- Hardy, The Epidemic Streets, 142–147.

- Arnold, Colonizing the Body, 210–214.

- Arnold, Colonizing the Body, 215–219.

- Evans, Death in Hamburg, 22–28.

- Duffy, The Sanitarians, 92–98.

- Valeska Huber, The Unification of the Globe by Disease? The International Sanitary Conferences, 1851–1938 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 25–32.

- Huber, The Unification of the Globe by Disease?, 45–53.

- Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice, 51–54.

- Evans, Death in Hamburg, 24–28.

- Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice, 59–63.

- Hardy, The Epidemic Streets, 142–147.

- Evans, Death in Hamburg, 32–36.

- Johnson, The Ghost Map, 78–89.

- Geison, The Private Science of Louis Pasteur, 56–63.

- Huber, The Unification of the Globe by Disease?, 45–53.

- Hardy, The Epidemic Streets, 203–210.

- Duffy, A History of Public Health in New York City, 1625–1866, 410–415.

- Geison, The Private Science of Louis Pasteur, 56–63.

- Huber, The Unification of the Globe by Disease?, 45–53.

- Hardy, The Epidemic Streets, 203–210.

Bibliography

- Anbinder, Tyler. Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Arnold, David. Colonizing the Body: State Medicine and Epidemic Disease in Nineteenth-Century India. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

- Benedict, Carol. Bubonic Plague in Nineteenth-Century China. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996.

- Coleman, William. Yellow Fever in the North: The Methods of Early Epidemiology. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987.

- Colgrove, James. State of Immunity: The Politics of Vaccination in Twentieth-Century America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

- Corbin, Alain. The Foul and the Fragrant: Odor and the French Social Imagination. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986.

- Davis, John P. “Cholera and the Russian Army, 1817–1825.” Slavic Review 25, no. 3 (1966): 433–448.

- Duffy, John. A History of Public Health in New York City, 1625–1866. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1968.

- Duffy, John. Sword of Pestilence: The New Orleans Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1853. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1966.

- Duffy, John. The Sanitarians: A History of American Public Health. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

- Durbach, Nadja. Bodily Matters: The Anti-Vaccination Movement in England, 1853–1907. Durham: Duke University Press, 2005.

- Echenberg, Myron. Plague Ports: The Global Urban Impact of Bubonic Plague, 1894–1901. New York: New York University Press, 2007.

- Ellis, John H. Yellow Fever and Public Health in the New South. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1992.

- Evans, Richard J. Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years 1830–1910. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Geison, Gerald L. The Private Science of Louis Pasteur. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

- Hamlin, Christopher. Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Hardy, Anne. The Epidemic Streets: Infectious Disease and the Rise of Preventive Medicine 1856–1900. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Harrison, Mark. Disease and the Modern World: 1500 to the Present. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004.

- Huber, Valeska. The Unification of the Globe by Disease? The International Sanitary Conferences, 1851–1938. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- Humphreys, Margaret. Yellow Fever and the South. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

- Johnson, Steven. The Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic. New York: Riverhead, 2006.

- Low, Michael Christopher. Imperial Mecca: Ottoman Arabia and the Indian Ocean Hajj. New York: Columbia University Press, 2020.

- Rosenberg, Charles E. The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

- Varlık, Nükhet. Plague and Empire in the Early Modern Mediterranean World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Worboys, Michael. Spreading Germs: Disease Theories and Medical Practice in Britain, 1865–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- World Health Organization. “Cholera Fact Sheet.” Updated 2024.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.17.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.