By Liza Picard

English Historian

How Long Could You Expect to Live?

Middle class men might live, on average, to 45. The average lives of workmen and labourers spanned just half that time. Children were lucky to survive their fifth birthdays. (The current life expectancy is around 80, and rising.)

The Miasma or ‘Bad Air’ Theory

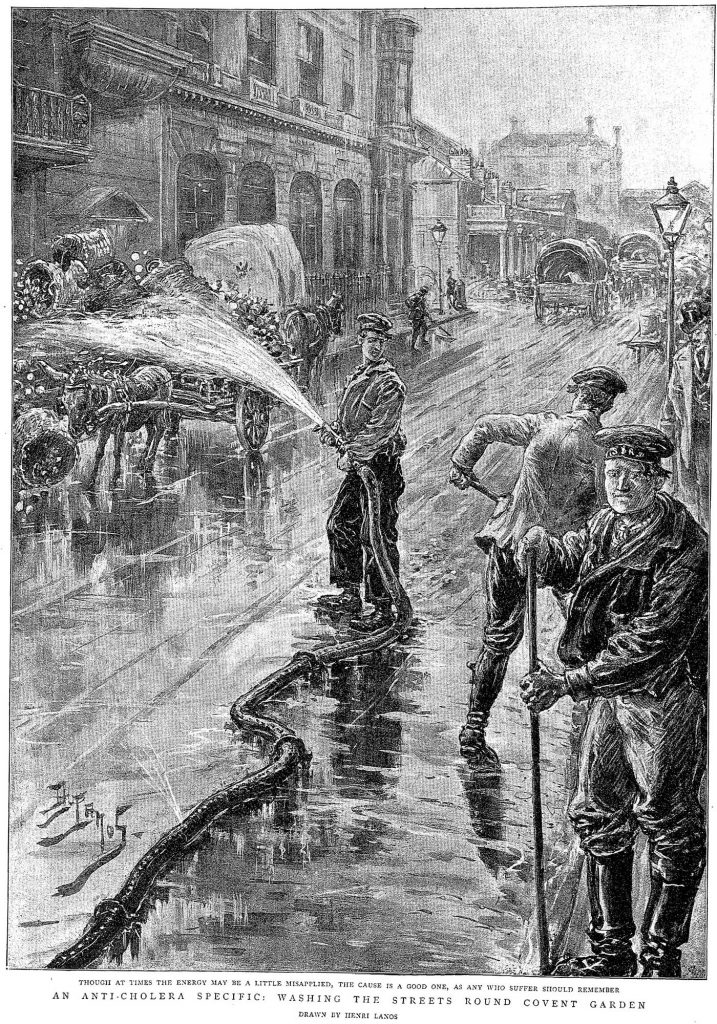

It was believed that bad smells caused disease. It was obvious; in poor districts, the air was foul and the death rate high. In the prosperous suburbs, no smells – therefore no disease.

Parliament was worried by the ‘Great Stink’ of 1858, when the Thames flowed with undiluted sewage, because the smell itself might kill the Members of Parliament in their debating chamber overlooking the river.

Florence Nightingale believed in the miasma theory. The miracles she achieved in the Crimean War hospitals resulted from her insistence that bad smells must be eradicated by thorough cleaning.

Killer Diseases

There were recurrent, terrible epidemics of cholera between 1832 and 1853. It took Dr John Snow years to persuade the establishment that cholera is a water-borne disease: nothing to do with bad smells.

Smallpox was endemic. From 1853 vaccination was compulsory. (Due to public opposition the law was repealed in 1909).

‘Consumption’ (tuberculosis) seemed to run in families. One after another, the girls would sicken, take to the sofa, and die. A light diet of jelly and port might comfort them, but their end was inescapable.

In the slums, prostitutes caught the sexually transmitted disease syphilis and infected their clients – who infected their wives. Again, there was no remedy, although mercury sometimes staved off the worst stages. From 1864 ‘known prostitutes’ working near ports and garrisons, who were found to have STDs, could be forcibly detained and treated. Due to public objections the law was repealed after 10 years.

Few upper-class ladies breast-fed their children. The babies’ immune systems would have benefited from their mother’s milk. Victorian nurseries were plagued by childhood diseases – measles, mumps, diphtheria, scarlet fever, rubella – that are mostly, now, a nightmare of the past.

Victorian employers had no duty to safeguard the health of their employees. The floral wallpapers in prosperous parlours, and the brilliant leaves on fashionable hats, could kill the workers who had close contact with the arsenic in the green dye. (The French long suspected the British of poisoning Napoleon in his prison on St Helena, by decorating his bedroom with green-patterned wallpaper). There was arsenic everywhere in the home – in the bathroom, to remove superfluous hair, in the garden to kill rats, in the kitchen to kill flies. A desperate wife had the means to murder her husband easily to hand.

Contraception and Childbirth

Victorian women might be almost continually pregnant, between marriage and menopause. Some contraceptive advice was available, and condoms could be bought, but only ‘under the counter’. Coitus interruptus remained the principal method of family limitation.

Childbirth was risky and painful. There was a wide belief that labour pains were imposed by God because Eve had sinned in the Garden of Eden. It took Dr Snow – the same man who discovered the source of cholera – to alleviate labour pains by administering chloroform. When Queen Victoria and the daughter of the Archbishop of Canterbury used it, anaesthesia had become respectable.

Mental Illness

Treatment for mental illness or nervous disorders had changed little since medieval times. Those sufferers lower down the social scale were locked up in County Asylums. Private ‘madhouses’ were often profitable institutions. Women might be locked away there by their husbands if he disapproved of her behaviour. Such dramatic stories were the subjects of popular fiction such as The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins.

Hospitals

The Victorian medical scene was not bad at all. In London, St Thomas’s, a medieval foundation, had to move to make way for a railway line; its new site was beside the Thames, where the air was now pure, due to Bazalgette’s magnificent new drainage system. Nevertheless Florence Nightingale insisted on open balconies and airy wards, to counteract any hospital-generated miasma, and her designs influenced hospital architecture for decades, in Britain and the Empire.

Many hospitals were founded to research into, and care for sufferers from, specific diseases such as tuberculosis. Their titles were grand – the Royal National Hospital for Chest Diseases, for example – but since they were privately funded they frequently ran out of money.

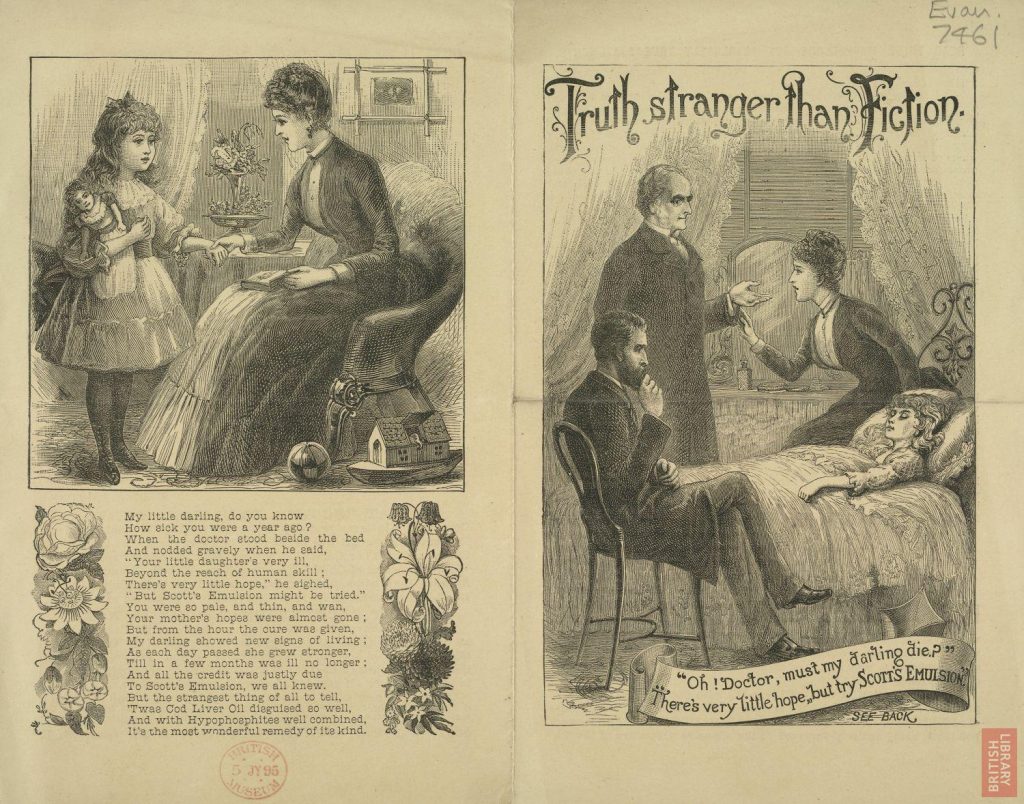

The middle classes deplored the reliance on quacks and quack medicines by the poor: the middle classes could afford proper medical care; the poor could not. Street vendors, ready to run if necessary, sold patent medicines on a ‘no cure, no pay’ basis. Fashionable charlatans could make a good living from their wares. John St. John Long claimed to cure consumption by liniment and medicated vapours. Even an appearance in the Old Bailey on a charge of manslaughter did not put him off for long. He could easily afford the fine, out of an income of £13,000. He died aged 36 – of consumption. A German charlatan, Dr Bossey, entertained vast crowds in Covent Garden but decamped when heckled by someone he believed to be a dissatisfied patient. In fact the heckler was a parrot.

The popular press was full of advertisements for dubious remedies. Kaye’s Worsdell’s Pills were ‘the best medicine which can be taken under all circumstances, as they require no restraint of diet or confinement during their use, and their timely assistance cures all complaints’: family size box 4s 6d. James Morison’s Universal Pill was compounded of aloes and cream of tartar; he died worth half a million pounds.

For a more specific approach, try Dr James’s Fever Powder, which contained antimony and ammonia in toxic amounts. Anderson’s Scots Pills for indigestion caused piles and chronic constipation. Steel’s Aromatic Lozenges promised to ‘repair the evils brought on by debauchery’ (a veiled reference to syphilis) but resulted only in a painful and dangerous inflammation.

Dr Collis Browne’s Chlorodine was marketed as a remedy for indigestion, but came in useful for almost anything, unsurprisingly since it contained a hefty dose of morphia, as well as kaolin for stomach pains. Morrison’s Pills resulted in numerous deaths – and a fortune for the maker. Several ‘remedies’ for babies’ wind, such as Godfrey’s Cordial, contained opium, which certainly quietened querulous infants, but overdoses could be fatal, especially when combined with gin.

Self-Medication

Chloroform was useful in an attack of toothache. Or the sufferer could try morphia, or laudanum, another derivative of opium. They could all be bought from chemists, no questions asked.

Advances in Medicine

Florence Nightingale changed nurses into highly trained professionals. The other branches of the medical profession, too, established examining and disciplinary bodies providing recognized qualifications. There were huge advances in medical knowledge. The death rate from post-operative shock and ‘hospital gangrene’ fell dramatically, now that operations were performed on an anaesthetized patient, in an operating theatre disinfected with carbolic, by a surgeon who had washed his hands in carbolic.

Originally published by the British Library, 10.14.2009, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.