To ask whether immigrants were sent to concentration camps is to recognize how far the machinery of exclusion extended. Immigrants were never safe. The very system of belonging was designed to erase them.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A Society Without Refuge

A regime that defined itself through exclusion could not tolerate ambiguity. Nazi Germany promised its citizens renewal through racial purity, yet within its borders lived immigrants, refugees, and foreign workers whose very presence contradicted the claim of a homogeneous people. Their existence forced the regime to decide: how should the foreigner be treated?

The answer was brutal but uneven. Some were enslaved in forced labor, others deported to camps, and still others lived under surveillance as tolerated outsiders. The question of whether immigrants were also sent to concentration camps exposes the fragility of Nazi ideology, for the camp system became a reservoir into which all categories of unwanted people could be poured.

The Precarious Position of Immigrants Before the War

Germany in the interwar years was no stranger to immigration. Polish seasonal workers had long crossed into Prussia to harvest crops, while Russian émigrés sought refuge from Bolshevik upheaval. Eastern European Jews, meanwhile, were present in Berlin and other cities, adding to the cultural diversity of the Weimar Republic.

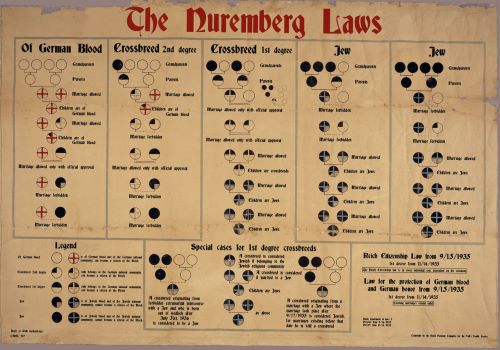

The Nazi seizure of power in 1933 converted this diversity into danger. Jews, regardless of national origin, were targeted first, stripped of citizenship and cast out of civic life.1 Slavic workers became subjects of suspicion, portrayed in propaganda as threats to German racial health. Even immigrants who might once have seemed assimilated found themselves reclassified by the racial state, their lives placed under a cloud of surveillance and precarity.

War, Occupation, and the Expansion of Forced Labor

The outbreak of war in 1939 created an unprecedented demand for labor. As German men were mobilized for military service, the Reich imported millions of foreign workers. By 1944, roughly 7.6 million foreigners lived within Germany, constituting nearly one quarter of the workforce.2

Treatment followed racial logic. Western Europeans from France or the Netherlands were exploited but granted relative leniency. Eastern Europeans were subjected to harsh restrictions, branded with badges, confined to guarded barracks, and fed starvation rations. Soviet prisoners of war were treated with particular brutality, with millions left to die from exposure and hunger.

The immigrant was thus both indispensable and despised. They sustained the German economy but were denied the dignity of recognition. Their presence highlighted the contradictions of a regime that claimed purity but survived on imported labor.

Case Studies: Polish Laborers and Soviet Prisoners

Polish Laborers

A young Polish farmhand wakes before dawn in a German village. On his jacket is a purple “P” badge stitched crudely to the fabric, branding him as foreign. At the edge of the field, a guard leans on his rifle. For the worker, every furrow of earth turned is both labor and survival, for defiance or exhaustion can end in punishment or deportation.

No group illustrates the contradictions of Nazi immigration policy more starkly than Polish workers. After the invasion of Poland in 1939, millions were transported into the Reich, some as “voluntary” recruits, most as forced deportees. Their numbers swelled to over 2.5 million by 1944, making them the largest foreign labor force.3

Poles were racially classified as “subhuman Slavs” and treated accordingly. They were required to wear identifying badges marked with a purple “P.” Regulations forbade them from using public transport freely, entering German cultural spaces, or even attending church with Germans. Contact with Germans, particularly sexual relations, was criminalized under the “racial defilement” laws, punishable by execution.4

Conditions for Polish laborers were appalling. They lived in overcrowded barracks, often behind barbed wire, subject to beatings and starvation diets. Those accused of infractions, whether shirking work or minor disobedience, could be publicly humiliated, imprisoned, or sent to concentration camps such as Buchenwald or Ravensbrück. Archival evidence shows that thousands of Polish workers perished within these camps, caught between the demands of labor exploitation and the logic of extermination.

The fate of Polish laborers reveals how Nazi Germany transformed immigration into a system of enslavement. They were neither citizens nor guests but a captive population whose humanity was deliberately erased, their lives treated as expendable fuel for the war economy.

Soviet Prisoners of War

Behind barbed wire in an open field near Minsk, thousands of men stand shivering in thin uniforms. The guards throw bread crusts over the wire, laughing as starving prisoners scramble for them. Winter has not yet arrived, but already bodies lie uncollected in the mud.

If Polish laborers reveal the logic of exploitation, Soviet POWs embody the logic of annihilation. Captured in staggering numbers after the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, an estimated 5.7 million Red Army soldiers fell into German hands. Of these, at least 3.3 million died in captivity through starvation, disease, or execution.5

Nazi racial ideology framed the Soviet prisoner not merely as an enemy combatant but as a racial inferior, a “Bolshevik subhuman” undeserving of protection under international law. Deprived of rations, left without shelter, and often penned behind barbed wire in open fields, they were deliberately exposed to the elements. Entire camps, such as those at Stalag 352 near Minsk, became sites of slow-motion extermination.

Many Soviet POWs who survived the initial catastrophe were later transported into the Reich as forced laborers. There, their treatment was scarcely better than in the camps. They were denied adequate food, subjected to beatings, and placed under constant threat of execution. Thousands were transferred to concentration camps such as Sachsenhausen and Mauthausen, where mortality rates were catastrophic.

The fate of Soviet POWs underscores the deadly intersection of immigrant presence and Nazi racial policy. They were foreigners within the Reich, but unlike Western Europeans, they were never meant to survive. Their presence in the camp system blurs the line between military captivity and racial extermination, revealing the radicalization of Nazi policy toward the East.

Immigrants in the Concentration Camp System

Foreigners entered concentration camps through multiple pathways. Jews of foreign nationality, whether long-term residents or refugees, were deported once the Final Solution began. Roma and Sinti, many of whom were itinerant or transnational, were rounded up for extermination.6 Polish and Soviet civilians could be sent to camps as punishment for infractions, while political refugees from Spain or elsewhere faced imprisonment as “undesirables.”

Not every immigrant or foreign worker ended up in Auschwitz, but the possibility loomed. Camps became the regime’s solution to difference, places where the boundaries of belonging could be brutally enforced. In this sense, the immigrant was always a potential prisoner, suspended between exploitation and annihilation.

Hierarchies of Foreignness

Nazi racial ideology built a hierarchy that determined treatment. Scandinavians and other “Aryan” foreigners were tolerated. Western Europeans were exploited but not targeted for mass murder. Eastern Europeans were enslaved, their survival uncertain. Jews and Roma, whether immigrants or not, were targeted for annihilation.

These gradations remind us that Nazi persecution was not a monolith but a layered system calibrated by race, politics, and utility. To be an immigrant in Nazi Germany was not to occupy one category but to exist within a hierarchy of suspicion, exploitation, and risk.

Conclusion: Exclusion as Political Identity

The treatment of immigrants in Nazi Germany reveals exclusion as the regime’s core principle. Immigrants were not merely outsiders but instruments in a system that sought to prove its racial logic through suffering. Polish laborers were enslaved, Soviet POWs starved, Jews deported, Roma exterminated. Even those granted relative leniency lived under suspicion.

To ask whether immigrants were sent to concentration camps is to recognize how far the machinery of exclusion extended. Camps became the ultimate answer to difference, absorbing those who could not be assimilated or whose labor was no longer useful. In the Reich, the immigrant was never safe, because the very system of belonging was designed to erase them.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Claudia Koonz, The Nazi Conscience (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2003), 112–116.

- Ulrich Herbert, Hitler’s Foreign Workers: Enforced Foreign Labor in Germany Under the Third Reich (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 41–45.

- Mark Spoerer, “Forced Labor in the Third Reich,” Norbert Wollheim Memorial, Fritz Bauer Institut, J.W. Goethe-Universität (Frankfurt am Main, 2010).

- Christopher R. Browning, Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (New York: HarperCollins, 1998), 58–63.

- Christian Streit, Keine Kameraden: Die Wehrmacht und die sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen 1941–1945 (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1978), 55–61.

- Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961), 325–330.

Bibliography

- Browning, Christopher R. Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. New York: HarperCollins, 1998.

- Herbert, Ulrich. Hitler’s Foreign Workers: Enforced Foreign Labor in Germany Under the Third Reich. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Hilberg, Raul. The Destruction of the European Jews. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961.

- Koonz, Claudia. The Nazi Conscience. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2003.

- Spoerer, Mark. “Forced Labor in the Third Reich.” Norbert Wollheim Memorial, Fritz Bauer Institut, J.W. Goethe-Universität (Frankfurt am Main, 2010): 453–482.

- Streit, Christian. Keine Kameraden: Die Wehrmacht und die sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen 1941–1945. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1978.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.25.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.