Freedom, in the American sense, was never bestowed from above. The hands that build its cities, till its soil, and carry its banners have always been the true authors of liberty’s story.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The story of American liberty has never been written solely in the language of constitutions or declarations. It has also been written in calloused hands, in the labor of those who built, tilled, forged, and struck for their right to be counted as free participants in the body politic. Before the first English settlers could even claim permanence on American soil, work had already become a site of protest. In 1619, a group of Polish craftsmen employed by the Virginia Company at Jamestown withheld their labor after being denied the vote in the colony’s assembly. They were skilled workers, brought to produce glass and pitch, but their grievance was not about wages or hours. It was about political recognition. Their strike, the first recorded in North America, compelled the colonial government to extend suffrage to all free men, regardless of national origin.1 In that act, the connection between labor and liberty was born: to work was to have a stake in freedom.

Over the next two centuries, that fragile principle endured amid the contradictions of servitude and slavery. The language of liberty became inseparable from economic struggle. Indentured servants, poor farmers, and enslaved Africans inhabited a common world of exploitation, even if their fates diverged sharply in law and race.2 As colonies matured, artisans and mechanics, the working backbone of urban America, began to claim a republican dignity rooted not in birth but in skill. By the eve of revolution, their demands for political inclusion were inseparable from their defense of economic independence. When the Sons of Liberty organized boycotts and mobs, the mechanics followed — not as hired hands, but as citizens in motion.3

The persistence of that laboring conscience shaped every epoch of American history that followed. From the mills of Lowell to the railroads of the Gilded Age, from the sweatshops of immigrant workers to the picket lines of the Great Depression, class struggle tested the nation’s ideals more severely than any foreign war. Economic liberty, long invoked by elites to justify profit, was redefined by workers as the right to organize, to bargain, and to live with dignity. In each generation, labor movements became both mirror and measure of democracy itself, the true proving ground of what equality meant in practice.4

By 1963, when the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. joined A. Philip Randolph and thousands of others at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, that long genealogy of struggle had come full circle. The march did not merely call for civil rights; it demanded economic justice, binding the rights of Black Americans to the rights of workers everywhere. King’s refrain, that freedom must include “jobs and freedom,” echoed Jamestown’s forgotten strikers across three and a half centuries. The laborer’s demand for recognition had become the republic’s moral test.5

From Servitude to Solidarity: Labor in the Colonial and Revolutionary Eras (1619–1776)

In the seventeenth century, the New World was imagined as a tabula rasa for freedom but built on layers of coercion. The promise of opportunity that lured migrants to the colonies masked a grim reality of indentured servitude. Tens of thousands of men and women, bound by contract, traded years of labor for passage across the Atlantic. Their bondage was not hereditary, but its moral logic differed little from slavery’s: both reduced the human being to a commodity of work. The servant’s plight, though temporary, exposed the contradiction at the heart of the English colonial enterprise, a society that preached liberty yet survived on unfree labor.6

By the time Nathaniel Bacon led his rebellion in 1676, class resentments among smallholders, servants, and freedmen had reached a breaking point. What began as a frontier war against Indigenous peoples evolved into a violent challenge to colonial authority. Bacon’s followers, overwhelmingly poor or recently freed laborers, turned their fury toward the ruling elite of Virginia, burning Jamestown itself.7 Though the revolt failed, its legacy lingered. Terrified of unified rebellion, the planter class tightened racial divisions, hardening the distinction between black slavery and white servitude. In this way, racial hierarchy became the ruling class’s answer to class solidarity.8

In the northern colonies, where slavery was less entrenched and industry slowly took root, labor began to organize along more autonomous lines. Artisans, printers, and carpenters in cities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia forged a new political identity as “mechanics,” skilled tradesmen who claimed both social respect and civic agency.9 These urban workers played a central role in pre-revolutionary protest. When Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765, it was not wealthy merchants but the mechanics who led the riots, erected liberty poles, and enforced boycotts.10 Their defiance was not only patriotic; it was class-inflected. The cry of “no taxation without representation” carried an implicit demand for recognition from those who labored, produced, and sustained the colonies’ prosperity.

As the Revolution approached, the language of labor found its way into the rhetoric of independence. The notion of the “free laborer” became an ideological cornerstone of republican virtue, a man who worked for himself, not for a master.11 The ideal drew from the lived experience of artisans who saw self-sufficiency as moral independence. But it also excluded vast numbers of others: enslaved Africans, Native Americans, and women, whose labor remained invisible or coerced. Even as the Continental Congress pledged liberty, its world of work remained bounded by inequality. Yet within those contradictions lay a radical potential. The Revolution’s promise that all men were created equal, once spoken, could never again be wholly confined to property owners. The rhetoric of equality would become the seedbed for later struggles, when the laboring poor would demand that the Republic finally live up to its own words.

The Industrial Republic and the Birth of the Labor Movement (1820–1877)

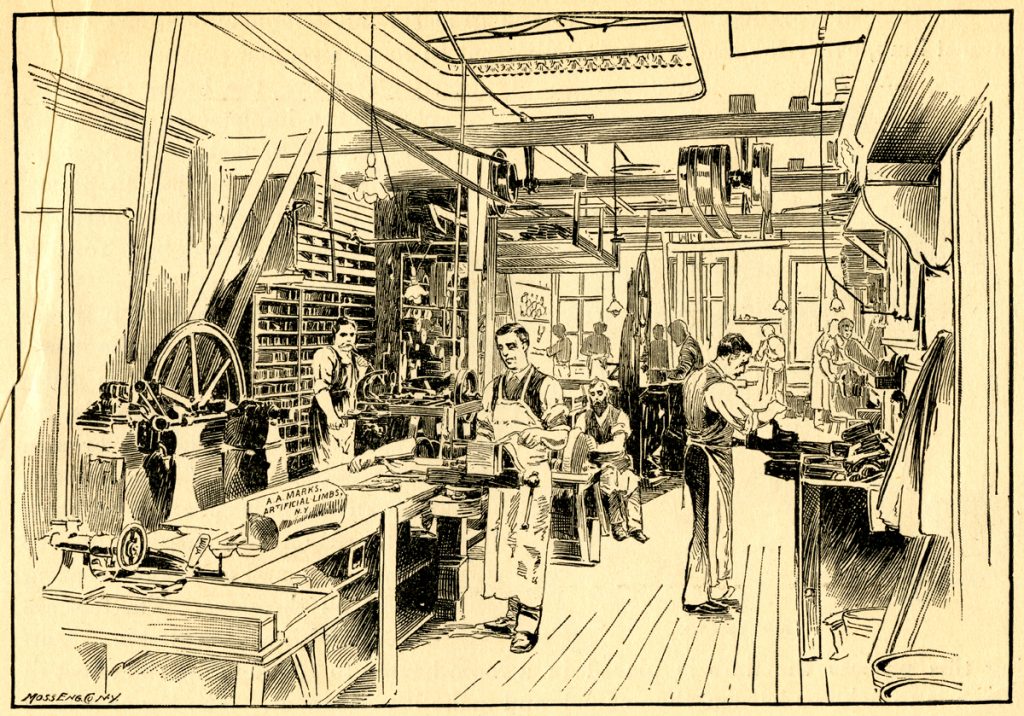

The early nineteenth century transformed the meaning of labor in America. As the Industrial Revolution reached U.S. shores, factories replaced workshops and mechanization redefined the relationship between skill and value. What had once been the artisan’s pride in craftsmanship became the operative’s dependence on the clock. The promise of the Republic, that work conferred dignity and autonomy, collided with a new industrial order where workers were measured by speed, not mastery.12

Among the earliest to challenge this transformation were the women of the Lowell textile mills in Massachusetts. Recruited as a moral labor force, “Lowell girls,” as they were called, they soon recognized the exploitative core of industrial paternalism. In 1834 and again in 1836, they organized strikes against wage cuts, invoking not merely economic grievance but republican principle: “Union is power,” declared one petition, insisting that liberty included the right to resist injustice.13 Though these early walkouts failed to achieve immediate reform, they signaled a decisive shift, the moral language of freedom now belonged to workers, not just property owners.

The 1830s and 1840s saw the birth of a wider labor consciousness. In cities like Philadelphia and New York, artisans and journeymen united under the banner of the Ten-Hour Movement, demanding a limit to the relentless workday.14 Labor newspapers such as the Mechanics’ Free Press and the Workingman’s Advocate became platforms for a new civic ideal: that democracy required leisure as well as labor, education as well as toil.15 In 1835, Philadelphia workers launched the first general strike in American history, coordinating across trades to secure the ten-hour day, a direct assertion that liberty could not coexist with exhaustion.16

The Civil War, often remembered as a moral crusade against slavery, also redefined labor in economic terms. The Union’s victory affirmed the “free labor” ideology championed by Abraham Lincoln, the belief that every man should rise by his own effort rather than depend on masters.17 Yet the postwar decades shattered that vision. Industrial capitalism expanded with ferocity, railroads crisscrossed the continent, and factory towns swelled with immigrant labor. The gulf between wealth and work grew to levels the founders had never imagined. By 1877, after years of wage cuts and economic depression, railway workers across the country erupted in what became the first national labor uprising. The Great Railroad Strike paralyzed transportation, drew violent federal suppression, and left more than one hundred dead.18 For the first time, the American state turned its guns not on foreign enemies but on its own working class.

Out of the ashes of 1877 arose the conviction that liberty without economic justice was hollow. The idea of the “industrial republic,” a nation where democratic ideals must govern the workplace as well as the ballot box, began to take hold.19 Labor had entered the political stage not merely as a social force but as a moral one. The same spirit that animated the Jamestown artisans and revolutionary mechanics now found new expression in the clamor of factory bells and the whistle of trains, the sound of a nation learning that freedom, to endure, must also be fair.

Class Consciousness and Radicalization in the Gilded Age (1877–1914)

After 1877, the industrial landscape of the United States was transformed by an explosion of corporate power and a new scale of urban labor. Factories multiplied, immigrant labor poured into cities, and a handful of industrialists (Carnegie, Rockefeller, Morgan) became the emblems of modern capitalism. While the nation celebrated its technological might, millions of workers endured poverty, disease, and ten-hour days without security or representation. The industrial order that had promised progress now revealed its contradiction: economic freedom for the few meant servitude for the many.20

Out of this crisis emerged the Knights of Labor, founded in 1869 but rising to national prominence after the Railroad Strike of 1877. Led by Terence V. Powderly, the organization preached cooperation over competition, seeking to unite all “producers” (skilled and unskilled, male and female, Black and white) into one common front. By 1886, it claimed nearly three-quarters of a million members.21 That same year, in Chicago, a labor rally for the eight-hour day erupted into the Haymarket bombing, killing police and civilians alike. The press condemned labor as anarchic; eight radical leaders were arrested and four hanged. The incident fractured the movement and burned into the public memory as proof that class conflict had become a battle over the soul of the Republic.22

In the strike-torn decades that followed, the American Federation of Labor (AFL), under Samuel Gompers, adopted a more pragmatic course. Rejecting the utopianism of the Knights, it organized skilled workers by craft and pursued “pure and simple unionism” – higher wages, shorter hours, and better conditions through collective bargaining rather than political revolution.23 This strategy secured limited gains but also reinforced the racial and gender barriers of the era. Women and Black workers were often excluded, and immigrants were treated with suspicion. The dream of solidarity shrank to a bargain within capitalism rather than a challenge to it.

Meanwhile, the industrial elite marshaled state power to crush dissent. When Pullman Company workers struck in 1894 to protest wage cuts and rent gouging in their company town, President Grover Cleveland sent federal troops to break the strike under the pretext of protecting the mails.24 Thirteen people died, and labor leader Eugene V. Debs was imprisoned for defying a court injunction. In jail, Debs read Marx and emerged as America’s most eloquent socialist, founding the Social Democratic Party and later the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).25 The IWW’s radical slogan, “An injury to one is an injury to all,” reasserted a universal ideal of labor that the AFL had abandoned.

By the eve of World War I, American labor stood divided but irrevocably transformed. The rhetoric of class had entered mainstream politics; the language of freedom now meant economic justice as well as political rights. What began with craftsmen demanding the vote in Jamestown had become a national reckoning with capital and democracy themselves. The “Gilded Age,” for all its glitter, revealed the iron truth beneath: that without labor’s power to resist, liberty would corrode into privilege.26

Depression, War, and the Rise of Organized Labor (1914–1945)

The First World War marked a turning point in the relationship between labor and the state. For the first time, the federal government recognized organized labor as essential to national stability. The Wilson administration’s creation of the National War Labor Board in 1918 secured wage increases, shorter hours, and the right of collective bargaining in return for labor’s no-strike pledge.27 Yet the fragile truce collapsed after the armistice. Employers launched an aggressive “open-shop” campaign, and the postwar Red Scare cast unionism as subversion. In 1919 alone, more than four million workers struck, from Boston police to the steel industry, only to face brutal repression, deportations, and propaganda equating class protest with Bolshevism.28 The promise of wartime partnership dissolved into suspicion.

The Great Depression revived the urgency of labor’s moral claim. As unemployment soared past 25 percent, breadlines replaced assembly lines, and the myth of boundless prosperity shattered. The New Deal sought not merely to rescue the economy but to re-found democracy on economic security. The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 and, more decisively, the Wagner Act of 1935 affirmed workers’ right to organize and bargain collectively, creating the National Labor Relations Board to enforce it.29 For the first time, the federal government stood as arbiter between labor and capital. Union membership exploded from fewer than three million in 1933 to more than eight million by 1940.30

A new generation of organizers recognized that industrial America required industrial unionism. The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), formed in 1935 under John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers, sought to unite all workers within an industry (steel, auto, rubber) regardless of craft, race, or skill.31 The sit-down strikes in Flint, Michigan (1936–37), where General Motors workers occupied plants until management yielded, became an emblem of labor’s rebirth.32 Union banners now spoke the language of citizenship: the right to security, voice, and dignity in the workplace.

World War II completed labor’s transformation from social outsider to national pillar. The War Labor Board stabilized wages, curtailed strikes, and institutionalized grievance procedures. Workers were celebrated as the “arsenal of democracy,” their productivity equated with patriotism.33 Women entered factories in unprecedented numbers, and African American migration to industrial centers reshaped the urban workforce. Yet even in wartime unity, tensions remained. Segregation persisted in defense industries until A. Philip Randolph’s threatened march on Washington in 1941 forced President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802 banning discrimination in defense employment.34 The struggle for economic and racial equality had fused.

By 1945, organized labor stood at the zenith of its power, a force millions strong, woven into the nation’s political fabric. But beneath triumph lay unease: postwar inflation, corporate resistance, and the coming Cold War would soon test labor’s newfound legitimacy. Still, the legacy of the New Deal and wartime mobilization endured. For a generation, the American worker believed, with reason, that democracy and economic justice could finally coexist.

Civil Rights and Economic Justice: Labor in the Age of Equality (1945–1963)

The postwar era opened with both promise and peril for organized labor. Having emerged from World War II as a central institution of American democracy, unions soon found themselves besieged by suspicion in the Cold War climate. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 curtailed many of the gains won under the New Deal: outlawing secondary boycotts, restricting strikes, and compelling union leaders to sign anti-communist affidavits.35 For many within the labor movement, this was more than legislative rollback; it was ideological betrayal. The same state that had once invoked workers as defenders of democracy now demanded conformity as proof of patriotism.36

Even so, the postwar boom gave labor new leverage. Union contracts raised wages, established health insurance and pensions, and brought millions of families into the middle class.37 Yet these gains were unequally shared. African American and Latino workers were often excluded from skilled trades and high-paying industrial jobs. Women, who had sustained the war economy, were pushed back into domestic roles or low-wage clerical work. The suburban prosperity of the 1950s rested on the continued marginalization of those whose labor remained invisible.38 Economic democracy, once imagined as universal, had narrowed into a racialized and gendered ideal of comfort.

A. Philip Randolph, whose wartime activism had forced Roosevelt’s hand, now became the elder statesman of a new movement linking labor rights and civil rights. His Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first major Black labor union, continued to press both employers and the federal government for equality.39 Randolph’s vision of freedom fused the demands of labor with those of racial justice. Jobs, housing, and dignity were not separable causes but one indivisible struggle. When he joined forces with Bayard Rustin in the early 1960s to organize a mass march on Washington, they revived a long-dormant alliance: the partnership of the laboring poor, the working class, and the moral conscience of the civil rights movement.40

On August 28, 1963, that alliance reached its crescendo. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom gathered more than 250,000 people on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, not only to demand voting rights, but to insist that civil liberty meant nothing without economic opportunity.41 Martin Luther King Jr.’s immortal “I Have a Dream” address was the culmination of a tradition stretching back to Jamestown: the belief that political recognition and labor dignity are two halves of the same freedom. King’s speech was preceded by labor leaders like Randolph and Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers, who framed the struggle in explicitly economic terms, for a living wage, full employment, and fair housing.42

In the closing decades of the long American labor story, King’s words gave that history its moral synthesis. “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere” was not only a plea against racial segregation; it was an indictment of economic inequality as the root of all oppression.43 The march signified the final convergence of two American revolutions, the labor movement and the civil rights movement, each born of the same faith that liberty without justice is hollow, and that democracy demands equality in both the ballot and the workplace.

Conclusion: The Work of Freedom

Across nearly three and a half centuries, the history of American labor has been the history of the nation’s conscience. From the Polish craftsmen at Jamestown demanding a vote in 1619 to the multiracial crowds gathered before the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, every generation has rediscovered the same truth: that freedom without dignity in work is an illusion. Political liberty may be declared, but it must also be enacted: in the workshop, the field, and the factory floor. The laborer’s demand for recognition, repeated through rebellion, strike, and march, became the nation’s recurring act of self-definition.44

The thread that binds these moments is not merely economic grievance but moral conviction. When the artisans of the eighteenth century refused taxation without representation, they spoke in the idiom of labor as citizenship. When the mill women of Lowell or the miners of Appalachia rose against exploitation, they did so in defense of a broader republican ideal: that equality must live where people labor, not only where they vote.45 And when King stood beside Randolph in 1963, he spoke not as a preacher apart from history but as its inheritor, giving voice to a centuries-old chorus, the belief that liberty is measured not by the power of the state, but by the empowerment of its workers.46

To trace that lineage is to see that labor was never the antagonist of freedom but its guarantor. Each expansion of rights in American history (political, racial, social) has rested on struggles born of work: the right to organize, to bargain, to live without hunger or humiliation. Yet the work of freedom remains unfinished. The same tensions that animated Bacon’s Rebellion, the Lowell strikes, and the March on Washington persist wherever inequality cloaks itself in rhetoric of opportunity. To remember these struggles is to recognize that democracy depends not on the silence of the governed but on the continual insistence of the working people who make it real.47

Freedom, in the American sense, was never bestowed from above. It has always been hammered out; in protest, in solidarity, and in labor itself. The nation’s enduring promise lies not in the wealth it creates, but in the fairness with which it honors those who create it. The hands that build its cities, till its soil, and carry its banners have always been the true authors of liberty’s story.48

Appendix

Footnotes

- Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: W.W. Norton, 1975), 75–76.

- Kathleen M. Brown, Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 183–190.

- Alfred F. Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution (Boston: Beacon Press, 1999), 25–30.

- Melvyn Dubofsky, Industrialism and the American Worker, 1865–1920 (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 1975), 41–45.

- William P. Jones, The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights (New York: W.W. Norton, 2013), 9–15.

- David W. Galenson, White Servitude in Colonial America: An Economic Analysis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 22–29.

- Stephen Saunders Webb, 1676: The End of American Independence (New York: Knopf, 1984), 104–112.

- Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia, 296–302.

- Gary B. Nash, The Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979), 88–95.

- Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765–1776 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1972), 54–60.

- Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788–1850 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 9–15.

- Jonathan Prude, The Coming of Industrial Order: Town and Factory Life in Rural Massachusetts, 1810–1860 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 47–52.

- Thomas Dublin, Women at Work: The Transformation of Work and Community in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1826–1860 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979), 98–105.

- Bruce Laurie, Artisans into Workers: Labor in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Hill and Wang, 1989), 72–75.

- Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788–1850, 121–130.

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 1: From Colonial Times to the Founding of the American Federation of Labor (New York: International Publishers, 1947), 115–118.

- Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 59–63.

- David O. Stowell, Streets, Railroads, and the Great Strike of 1877 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 11–18.

- Melvyn Dubofsky, Industrialism and the American Worker, 1865–1920, 3–7.

- Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011), 155–162.

- Leon Fink, Workingmen’s Democracy: The Knights of Labor and American Politics (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983), 18–25.

- James Green, Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement, and the Bombing that Divided Gilded Age America (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006), 176–183.

- Irving Bernstein, The Lean Years: A History of the American Worker, 1920–1933 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1960), 12–16.

- David Ray Papke, The Pullman Case: The Clash of Labor and Capital in Industrial America (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1999), 77–82.

- Nick Salvatore, Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982), 115–121.

- Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, 1492–Present (New York: Harper Perennial, 1980), 251–257.

- Robert H. Zieger, America’s Great War: World War I and the American Experience (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000), 189–192.

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 6: The Postwar Struggles, 1918–1920 (New York: International Publishers, 1987), 41–46.

- Nelson Lichtenstein, State of the Union: A Century of American Labor (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 27–31.

- Melvyn Dubofsky and Foster Rhea Dulles, Labor in America: A History (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2004), 196–198.

- John L. Lewis, The CIO: Its Story (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949), 14–19.

- Sidney Fine, Sit-Down: The General Motors Strike of 1936–1937 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969), 102–109.

- Susan M. Hartmann, The Home Front and Beyond: American Women in the 1940s (Boston: Twayne, 1982), 73–77.

- Paula F. Pfeffer, A. Philip Randolph, Pioneer of the Civil Rights Movement (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990), 112–118.

- James A. Gross, The Reshaping of the National Labor Relations Board: National Labor Policy in Transition, 1937–1947 (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1981), 198–203.

- Nelson Lichtenstein, Labor’s War at Home: The CIO in World War II (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 219–225.

- Irving Bernstein, The Turbulent Years: A History of the American Worker, 1933–1941 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970), 345–348.

- Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (New York: Basic Books, 1988), 92–99.

- Paula F. Pfeffer, A. Philip Randolph, Pioneer of the Civil Rights Movement, 178–185.

- John D’Emilio, Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin (New York: Free Press, 2003), 356–362.

- William P. Jones, The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights, 135–142.

- Robert H. Zieger, For Jobs and Freedom: Race and Labor in America Since 1865 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007), 183–189.

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” April 16, 1963, in Why We Can’t Wait (New York: Signet, 1964), 86.

- David Montgomery, The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865–1925 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 1–4.

- Thomas Dublin, Women at Work: The Transformation of Work and Community in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1826–1860, 142–145.

- Robert H. Zieger, For Jobs and Freedom: Race and Labor in America Since 1865, 189–191.

- Nelson Lichtenstein, State of the Union: A Century of American Labor, 268–271.

- Eric Foner, The Story of American Freedom (New York: W.W. Norton, 1994), 345–348.

Bibliography

- Bernstein, Irving. The Lean Years: A History of the American Worker, 1920–1933. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1960.

- Bernstein, Irving. The Turbulent Years: A History of the American Worker, 1933–1941. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970.

- Brown, Kathleen M. Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- D’Emilio, John. Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin. New York: Free Press, 2003.

- Dubofsky, Melvyn. Industrialism and the American Worker, 1865–1920. Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 1975.

- Dubofsky, Melvyn, and Foster Rhea Dulles. Labor in America: A History. Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2004.

- Dublin, Thomas. Women at Work: The Transformation of Work and Community in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1826–1860. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

- Fine, Sidney. Sit-Down: The General Motors Strike of 1936–1937. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969.

- Fink, Leon. Workingmen’s Democracy: The Knights of Labor and American Politics. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983.

- Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- Foner, Eric. The Story of American Freedom. New York: W.W. Norton, 1994.

- Foner, Philip S. History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 1: From Colonial Times to the Founding of the American Federation of Labor. New York: International Publishers, 1947.

- Foner, Philip S. History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 6: The Postwar Struggles, 1918–1920. New York: International Publishers, 1987.

- Galenson, David W. White Servitude in Colonial America: An Economic Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- Green, James. Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement, and the Bombing that Divided Gilded Age America. New York: Pantheon Books, 2006.

- Gross, James A. The Reshaping of the National Labor Relations Board: National Labor Policy in Transition, 1937–1947. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1981.

- Hartmann, Susan M. The Home Front and Beyond: American Women in the 1940s. Boston: Twayne, 1982.

- King, Martin Luther, Jr. “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” In Why We Can’t Wait. New York: Signet, 1964.

- Laurie, Bruce. Artisans into Workers: Labor in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Hill and Wang, 1989.

- Lewis, John L. The CIO: Its Story. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949.

- Lichtenstein, Nelson. Labor’s War at Home: The CIO in World War II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Lichtenstein, Nelson. State of the Union: A Century of American Labor. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Maier, Pauline. From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765–1776. New York: W.W. Norton, 1972.

- May, Elaine Tyler. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. New York: Basic Books, 1988.

- Montgomery, David. The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865–1925. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia. New York: W.W. Norton, 1975.

- Nash, Gary B. The Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979.

- Papke, David Ray. The Pullman Case: The Clash of Labor and Capital in Industrial America. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1999.

- Pfeffer, Paula F. A. Philip Randolph, Pioneer of the Civil Rights Movement. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990.

- Prude, Jonathan. The Coming of Industrial Order: Town and Factory Life in Rural Massachusetts, 1810–1860. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Salvatore, Nick. Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982.

- Stowell, David O. Streets, Railroads, and the Great Strike of 1877. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Webb, Stephen Saunders. 1676: The End of American Independence. New York: Knopf, 1984.

- White, Richard. Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America. New York: W.W. Norton, 2011.

- Wilentz, Sean. Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788–1850. New York: Oxford University Press, 1984.

- Young, Alfred F. The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution. Boston: Beacon Press, 1999.

- Zieger, Robert H. America’s Great War: World War I and the American Experience. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000.

- Zieger, Robert H. For Jobs and Freedom: Race and Labor in America Since 1865. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007.

- Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States, 1492–Present. New York: Harper Perennial, 1980.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.21.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.