The war endured not simply because armies marched, but because stories held. Where belief fractured, authority faltered.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: War as a Narrative Crisis

The Hundred Years’ War was not merely a military contest between England and France. It was a prolonged crisis of meaning. Spanning more than a century, punctuated by truces, dynastic shifts, plagues, and economic strain, the conflict repeatedly forced rulers to answer a question more dangerous than any battlefield defeat: why must this war continue?

Unlike short campaigns justified by immediate threats, the Hundred Years’ War demanded explanation across generations. Kings died, heirs inherited claims they did not originate, and populations were asked to endure taxation, conscription, and devastation for causes that often appeared remote or abstract. War, in this context, was not self-justifying. It had to be narrated into legitimacy.

This necessity transformed political communication into a central instrument of rule. English and French monarchs alike confronted a persistent legitimacy problem. Military outcomes were inconsistent. Victories could not be guaranteed, defeats could not be ignored, and prolonged stalemate risked eroding loyalty. The solution was not silence, but story. Rulers framed the war as lawful inheritance, sacred duty, defensive necessity, or providential trial, depending on circumstance and audience. Narrative became governance by other means.

Crucially, this narrative labor did not operate in a modern media environment. There were no centralized presses, no uniform messages, and no expectation of factual precision as understood today. Instead, information circulated through proclamation, performance, ritual, and selectively crafted written accounts. Meaning traveled orally, socially, and unevenly. In such a world, exaggeration was not exceptional but functional, while moral framing mattered more than empirical accuracy.

The endurance of the conflict heightened the stakes of narrative control. Each renewal of hostilities reopened questions that rulers preferred to keep settled. Why does the king possess the right to rule here? Why is the enemy unjust, impious, or illegitimate? Why does suffering continue even when victory appears elusive? These were not abstract concerns. They shaped taxation compliance, military participation, and popular tolerance for hardship.

Understanding propaganda in the Hundred Years’ War therefore requires treating war itself as a narrative crisis. Political authority depended not only on arms, but on the continuous management of belief. Rulers did not merely fight battles. They fought interpretive struggles over legitimacy, morality, and memory, using the cultural tools available to them.

The war endured because it was continually explained. Its violence was sustained because it was repeatedly made meaningful. In that sense, propaganda was not an accessory to medieval warfare. It was one of its conditions of possibility.

References

- Allmand, Christopher. The Hundred Years War. Cambridge University Press.

- Rogers, Clifford J., editor. The Wars of Edward III: Sources and Interpretations. Boydell Press.

- Sumption, Jonathan. The Hundred Years War, Volume I: Trial by Battle. Faber & Faber.

Defining Propaganda in a Medieval Political Culture

Applying the concept of propaganda to the medieval world requires careful restraint. The word itself belongs to a later age of bureaucratic states, mass literacy, and centralized information systems. To use it uncritically risks imposing modern expectations of coordination, saturation, and ideological uniformity onto a political culture that operated very differently. Yet to avoid the concept altogether would obscure the deliberate and strategic ways medieval rulers shaped political meaning. The challenge, therefore, is not whether propaganda existed, but how it functioned under medieval conditions.

In what follows, propaganda is understood not as a totalizing system of information control, but as a set of intentional narrative practices deployed by political authority to legitimize power, justify violence, and stabilize loyalty. Medieval propaganda did not seek to convince everyone of everything. Rather, it worked to frame events within morally intelligible stories that aligned kingship with law, custom, and divine favor. Its success depended less on factual persuasion than on symbolic resonance. What mattered was not whether claims could be verified, but whether they fit within accepted frameworks of belief.

This distinction is crucial because medieval political culture did not prioritize empirical accuracy in the modern sense. Truth was relational and moral, not statistical. A king who lost a battle could still be righteous if defeat was interpreted as divine testing rather than failure. An enemy could be condemned as illegitimate without exhaustive legal proof if their actions violated perceived social or sacred norms. Propaganda operated within these expectations, shaping interpretation rather than inventing reality wholesale.

Equally important is recognizing that medieval propaganda was constrained. Rulers could not endlessly contradict lived experience without consequence. Excessive distortion risked disbelief, ridicule, or erosion of trust, especially among elites whose cooperation was essential to governance. Narrative authority therefore depended on plausibility within shared cultural assumptions. Medieval propaganda was persuasive not because it overwhelmed audiences, but because it worked within familiar moral vocabularies, reinforcing what people were prepared to believe about kingship, justice, and war.

References

- Reynolds, Susan. Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, 900–1300. Oxford University Press.

- Kantorowicz, Ernst H. The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology. Princeton University Press.

The Media Ecology of Late Medieval Europe

Political communication during the Hundred Years’ War operated within a media environment radically different from that of the modern state. Information moved slowly, unevenly, and through overlapping oral and written channels. Literacy, while expanding among clerics, officials, and urban elites, remained limited for much of the population. As a result, political meaning was rarely encountered through silent reading. It was heard, watched, and collectively experienced. Authority spoke most powerfully when it was performed.

Oral transmission dominated this environment. Royal proclamations were read aloud in town squares, market halls, and churches, transforming written texts into public speech acts. Sermons linked contemporary events to scripture, framing war within a providential narrative that ordinary listeners could recognize and absorb. News of battles and treaties spread through travelers, merchants, and soldiers, often reshaped with each retelling. Accuracy mattered less than coherence and emotional force. Information survived when it was memorable.

Written culture nevertheless played a vital role, particularly among political elites. Chronicles, letters, and administrative records provided durable narratives that could be consulted, copied, and cited. These texts did not merely record events. They interpreted them. Chroniclers selected what to include, what to omit, and how to explain outcomes, often aligning their accounts with the interests of patrons or prevailing political orthodoxies. Written narratives gave propaganda longevity, even as oral performance gave it reach.

Performance occupied a critical space between speech and text. Minstrels, jongleurs, and poetic performers transformed political narratives into song and story, embedding royal victories, heroic kingship, and enemy villainy within entertainment. Pageantry, ceremonial entries, and symbolic rituals reinforced these messages visually. Heraldry, banners, and clothing communicated allegiance and legitimacy without words. In such contexts, propaganda was not simply told. It was enacted.

This media ecology shaped the nature of medieval propaganda itself. Messages had to be simple, repetitive, and morally legible. Complexity dissolved in transmission. Nuance yielded to emblematic figures and clear oppositions. Kings were righteous or tested, enemies were treacherous or barbarous, victories were signs of favor, defeats moments of trial. The medium did not merely carry the message. It structured what kinds of messages could survive at all.

References

- Clanchy, M. T. From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Contamine, Philippe. War in the Middle Ages. Blackwell.

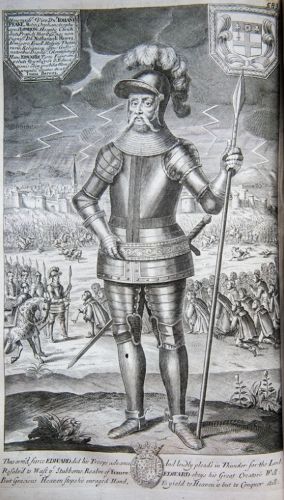

English Propaganda: Claim, Conquest, and Chivalric Destiny

English propaganda during the Hundred Years’ War was shaped by a fundamental political problem: the English crown advanced an extraordinary claim to rule France. This was not a defensive war fought on English soil, but an assertion of dynastic entitlement across the Channel. Such a claim could not rely solely on force. It required continuous narrative reinforcement to appear lawful rather than predatory, inherited rather than invented. English propaganda therefore centered on transforming conquest into legitimacy.

Genealogy played a central role in this effort. English rulers framed their claim to the French throne as a matter of rightful succession rather than ambition. Legal arguments concerning inheritance were simplified and moralized for public consumption. The war was presented not as an invasion, but as the recovery of a stolen crown. This framing allowed violence to be recast as restoration, aligning military aggression with justice rather than disruption. The legitimacy of the claim mattered less than the plausibility of the story sustaining it.

Military success was then woven into this narrative as confirmation of divine favor. Victories were amplified, defeats minimized or reinterpreted, and chance outcomes recast as providential signs. Battles became moral verdicts. When English armies triumphed against larger forces, the result was framed as evidence that God favored the rightful king. When campaigns faltered, silence or selective explanation preserved the overarching narrative. The war’s meaning, not its exact course, was what propaganda sought to control.

Chivalric ideology provided another powerful tool. English kings portrayed themselves as ideal warrior-monarchs, embodying courage, honor, and restraint. Warfare was aestheticized through the language of knighthood, tournament culture, and heroic masculinity. Violence was framed as noble rather than brutal, disciplined rather than destructive. This presentation appealed particularly to the aristocracy, whose participation was essential to sustained campaigning and whose values shaped elite opinion.

Popular transmission reinforced these themes through performance. Songs and stories celebrating English valor circulated widely, carried by minstrels and soldiers alike. Heroic episodes were simplified, repeated, and embellished as they spread. Individual kings became central characters in a moral drama, their courage standing in for national righteousness. The enemy, by contrast, was depicted as cowardly, decadent, or treacherous, reinforcing the moral clarity of English action.

Yet English propaganda remained vulnerable to contradiction. Prolonged occupation, fiscal strain, and periodic reversals exposed the limits of narrative control. Maintaining belief required constant renewal. Claims had to be restated, victories remembered, and failures reframed. English propaganda thus reveals both the ambition and fragility of medieval political storytelling. It could sustain belief for decades, but never without effort, adjustment, and risk.

References

- Sumption, Jonathan. The Hundred Years War, Volumes I–III. Faber & Faber.

- Vale, Malcolm. War and Chivalry: Warfare and Aristocratic Culture in England, France, and Burgundy at the End of the Middle Ages. University of Georgia Press.

French Propaganda: Defense, Restoration, and Sacred Kingship

French propaganda during the Hundred Years’ War emerged from a position of crisis rather than ambition. Unlike England, France did not need to justify invasion or dynastic expansion. It needed to explain survival. Repeated military defeats, internal factionalism, and foreign occupation threatened not only territorial control but the very legitimacy of the French crown. Propaganda therefore focused on preserving the moral authority of kingship in the face of humiliation and disorder.

Central to this effort was the concept of sacred monarchy. The French king was presented not merely as a political ruler but as the divinely anointed guardian of the realm. His authority derived from consecration, tradition, and continuity rather than battlefield success. Even when armies failed, the king’s legitimacy remained intact because it rested on divine selection rather than military fortune. This distinction allowed defeat to be framed as trial rather than judgment.

Defensive rhetoric dominated French narrative strategy. English advances were depicted not as lawful claims but as acts of usurpation and sacrilege. The war was cast as a struggle to restore violated order rather than to acquire new power. English occupation became evidence of injustice, reinforcing the moral necessity of resistance. This framing transformed endurance into virtue and delay into patience rather than weakness.

Propaganda also worked to reassemble fractured loyalty within France itself. Civil war, competing factions, and regional autonomy threatened royal authority as much as English arms. Narrative emphasis on unity, obedience, and the king’s role as guarantor of peace sought to suppress internal dissent. Loyalty to the crown was presented as loyalty to France itself, collapsing political allegiance into moral obligation.

As fortunes shifted, French propaganda adapted. Military recovery and territorial reconquest were portrayed not as sudden reversals but as the rightful restoration of divine order. Victory narratives emphasized purification and renewal rather than conquest. The return of lands and authority was framed as inevitable once moral alignment had been restored. Success confirmed what propaganda had long asserted: that the king’s cause was just, even when temporarily obscured.

French propaganda thus reveals a distinct political logic. Where English narratives sought to normalize conquest, French narratives worked to sanctify endurance. Kingship was defended not by denying failure, but by absorbing it into a providential framework. In doing so, French rulers preserved legitimacy through catastrophe and positioned recovery as fulfillment rather than transformation.

References

- Beaune, Colette. The Birth of an Ideology: Myths and Symbols of Nation in Late-Medieval France. University of California Press.

- Contamine. War in the Middle Ages.

Moral Geography and the Construction of the Enemy

Propaganda during the Hundred Years’ War relied heavily on the creation of moral geography. Political conflict was translated into ethical contrast, dividing the world into spaces of legitimacy and corruption, order and transgression. The enemy was not merely opposed in interest but condemned in character. Such moral mapping simplified a complex and protracted conflict into intelligible categories that justified violence and sustained loyalty.

English and French narratives alike portrayed the opposing side as fundamentally disordered. The enemy was described as treacherous, faithless, or morally degenerate, lacking the virtues necessary for rightful rule. These depictions drew on existing cultural stereotypes and moral vocabularies rather than empirical observation. The purpose was not accuracy, but explanation. By presenting the enemy as inherently flawed, defeat could be framed as temporary misfortune and victory as moral correction.

This moral othering served several political functions. It insulated rulers from blame by locating responsibility for suffering outside the community. Hardship became the result of enemy wickedness rather than royal failure. It also reinforced internal cohesion. Loyalty was strengthened not only by praise of the self but by condemnation of the other. Shared hostility created shared identity, even in the absence of consistent success.

Importantly, these constructions were flexible rather than fixed. The enemy’s vices shifted according to circumstance, emphasizing cowardice after retreat, cruelty after raids, or illegitimacy when claims were pressed. Moral geography was therefore a dynamic tool, continuously reshaped to meet political needs. Through it, medieval propaganda transformed war into an ethical landscape where violence appeared not only necessary but righteous.

References

- Spiegel, Gabrielle M. Romancing the Past: The Rise of Vernacular Prose Historiography in Thirteenth-Century France. University of California Press.

- Partner, Nancy. Serious Entertainments: The Writing of History in Twelfth-Century England. University of Chicago Press.

Exaggeration, Suppression, and Medieval “Fake News”

Exaggeration was not an aberration in medieval political communication. It was a structural feature. In a world where information traveled orally, selectively, and slowly, precision was neither expected nor required. Numbers swelled, victories expanded, and defeats contracted as narratives moved from court to town to countryside. Such distortions were not necessarily understood as deceit. They were accepted conventions through which events were made legible and meaningful.

Victory narratives illustrate this clearly. Successful engagements were routinely amplified, enemy losses inflated, and the significance of the outcome magnified beyond its immediate military impact. A skirmish could become a turning point. A tactical success could be framed as a moral reckoning. These narratives served to sustain morale, justify continued taxation, and reassure populations that sacrifice had purpose. What mattered was not proportionality, but reassurance.

Suppression functioned alongside exaggeration. Defeats were often omitted entirely from public discourse or reframed in ways that neutralized their political danger. Silence itself became a communicative act. When losses could not be ignored, they were interpreted as temporary trials, betrayals by subordinates, or moments of divine testing. Responsibility was displaced upward toward providence or downward toward flawed agents, preserving the moral authority of the crown.

The term “fake news” must therefore be used with caution. Medieval audiences did not operate within a culture of journalistic verification or statistical accountability. Falsehood was judged less by correspondence to fact than by alignment with moral expectation. A narrative that contradicted lived experience too sharply risked disbelief, but one that bent reality within accepted bounds could reinforce trust rather than undermine it. Deception was constrained not by truth norms, but by plausibility within shared belief systems.

Nevertheless, rulers did at times circulate claims they knew to be false. These instances reveal deliberate manipulation rather than customary exaggeration. Inflated casualty figures, invented enemy atrocities, or fabricated victories crossed the line from convention into calculation. Such practices were risky, but often effective in the short term. They demonstrate that medieval political actors understood the power of misinformation, even without modern terminology, and were willing to exploit it when authority appeared threatened.

References

- Given-Wilson, Chris. Chronicles: The Writing of History in Medieval England. Hambledon Press.

- Geary, Patrick J. Phantoms of Remembrance: Memory and Oblivion at the End of the First Millennium. Princeton University Press.

Chroniclers as Political Actors, Not Neutral Observers

Medieval chroniclers occupied a position of perceived authority that made their work particularly powerful as a vehicle for political narrative. They were often clerics, court affiliates, or individuals dependent on noble patronage, embedded within the very power structures they described. Their writings were not detached records of events but interpretive constructions shaped by loyalty, obligation, and audience expectation. To read medieval chronicles as neutral reportage is to misunderstand both their purpose and their function.

Chroniclers selected events with intention. What they chose to record, emphasize, or omit reflected political priorities rather than comprehensive documentation. Victories received detailed treatment, defeats were abbreviated or reframed, and controversial episodes were softened or displaced. Chronology itself could be manipulated, with causation reordered to support moral conclusions. The chronicle was less a mirror of events than a framework through which events were made intelligible and acceptable.

Patronage exerted a subtle but decisive influence. Chroniclers writing under royal or noble protection understood the boundaries of acceptable interpretation. Open criticism of a patron’s legitimacy or competence was rare, not necessarily because chroniclers lacked awareness, but because their survival depended on discretion. Praise could be effusive, blame strategically redirected. Enemy leaders were caricatured, while allied figures were ennobled. The resulting narratives reinforced existing power rather than interrogated it.

Genre conventions further shaped chronicling as propaganda. Medieval historiography privileged moral instruction over empirical reconstruction. Events were valuable insofar as they illustrated virtue, vice, divine justice, or providential order. This moral orientation aligned naturally with political messaging. Kings were judged not by administrative success but by perceived righteousness. Outcomes were interpreted as confirmations or warnings, embedding political authority within a broader ethical universe.

Recognizing chroniclers as political actors does not render their accounts useless. On the contrary, it clarifies their value. Chronicles reveal not only what rulers wanted remembered, but how legitimacy was imagined, defended, and contested. They are records of belief as much as of action. In the context of the Hundred Years’ War, chroniclers functioned as narrative engineers, shaping memory in service of authority and ensuring that war, however chaotic in reality, appeared ordered in retrospect.

References

- Froissart, Jean. Chroniques. Various critical editions.

- Spiegel, Gabrielle M. The Past as Text: The Theory and Practice of Medieval Historiography. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Conclusion: Propaganda, Power, and the Limits of Belief

Propaganda in the Hundred Years’ War was neither crude fabrication nor total narrative domination. It was a sustained, adaptive effort to manage meaning in a political world where authority depended on shared belief rather than coercion alone. English and French rulers alike understood that war could not be fought indefinitely on force. It had to be explained, justified, and morally framed. Narrative became an essential companion to arms.

At the same time, medieval propaganda operated within clear constraints. Rulers could shape interpretation, but they could not fully control experience. Excessive distortion risked disbelief, especially among elites whose cooperation was indispensable. Propaganda succeeded when it aligned with existing moral expectations, ritual practices, and social hierarchies. It failed when it strayed too far from what audiences were prepared to accept. Power, in this sense, was persuasive rather than absolute.

The Hundred Years’ War thus reveals a political culture acutely aware of narrative vulnerability. Legitimacy was never settled once and for all. It had to be continuously renewed through performance, memory, and interpretation. Kingship survived defeat not by denying reality, but by reinterpreting it within frameworks of providence, justice, and endurance. Propaganda functioned less as deception than as mediation between authority and uncertainty.

Medieval propaganda anticipates modern struggles over information without replicating them. It lacked the scale and uniformity of later state systems, but it demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of how belief sustains power. The war endured not simply because armies marched, but because stories held. Where belief fractured, authority faltered. Where narrative coherence remained, even failure could be endured.

References

- Boucheron, Patrick. Power and Narrative in Medieval Europe. Polity.

- Lake, Peter, and Steven Pincus, editors. The Politics of the Public Sphere in Early Modern England. Manchester University Press.

Bibliography

- Allmand, Christopher. The Hundred Years War: England and France at War c.1300–c.1450. Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Beaune, Colette. The Birth of an Ideology: Myths and Symbols of Nation in Late-Medieval France. University of California Press, 1991.

- Clanchy, M. T. From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307. Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

- Contamine, Philippe. War in the Middle Ages. Blackwell, 1980.

- Froissart, Jean. Chronicles. Penguin Classics, 1978.

- Geary, Patrick J. Phantoms of Remembrance: Memory and Oblivion at the End of the First Millennium. Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Given-Wilson, Chris. Chronicles: The Writing of History in Medieval England. Hambledon Press, 2004.

- Kantorowicz, Ernst H. The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology. Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Partner, Nancy F. Serious Entertainments: The Writing of History in Twelfth-Century England. University of Chicago Press, 1977.

- Reynolds, Susan. Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, 900–1300. Clarendon Press, 1997.

- Rogers, Clifford J., editor. The Wars of Edward III: Sources and Interpretations. Boydell Press, 1999.

- Spiegel, Gabrielle M. Romancing the Past: The Rise of Vernacular Prose Historiography in Thirteenth-Century France. University of California Press, 1993.

- —-. The Past as Text: The Theory and Practice of Medieval Historiography. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

- Sumption, Jonathan. The Hundred Years War, Volume I: Trial by Battle. Faber & Faber, 1990.

- —-. The Hundred Years War, Volume II: Trial by Fire. Faber & Faber, 2001.

- Vale, Malcolm. War and Chivalry: Warfare and Aristocratic Culture in England, France, and Burgundy at the End of the Middle Ages. University of Georgia Press, 1981.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.25.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.