Photography has never been a neutral witness to history. It has functioned as a persuasive medium shaped by human intention, social expectation, and institutional power.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Photography and the Illusion of Mechanical Truth

From its earliest public reception in the nineteenth century, photography was greeted as a technological marvel capable of transcending human subjectivity. Unlike painting or drawing, the photograph appeared to be produced by light itself, captured mechanically and fixed onto a surface without the interpretive hand of the artist. This perceived neutrality granted photography an authority unmatched by previous visual media. Courts, newspapers, scientists, and governments alike embraced photographs as evidence, assuming that what the camera recorded must correspond directly to reality.

Yet this faith in mechanical truth was always more cultural than technical. Cameras did not operate independently of human intention. Choices about framing, exposure, staging, and selection were present from the beginning, even before deliberate alteration entered the process. The belief that photography was inherently truthful rested on a misunderstanding of how images are made and how meaning is assigned to them. The apparatus might be mechanical, but its use was decisively human.

Crucially, manipulation did not emerge as a corruption of an otherwise pure medium. It arose alongside photography itself. From retouching negatives to combining multiple images, early photographers quickly discovered that photographs could be adjusted, improved, or reshaped to meet aesthetic, social, or ideological expectations. These practices were often justified as technical corrections or artistic refinements rather than deceptions. The boundary between acceptable enhancement and misleading alteration was neither fixed nor universally agreed upon.

What follows argues that photographic manipulation is not an anomaly introduced by modern technology, but a structural feature of photography’s history. Long before digital tools made alteration accessible and visible, images were being modified to persuade, reassure, memorialize, or control. By tracing the evolution of photo manipulation from the mid-nineteenth century through the early twentieth century, this study challenges the enduring myth of photographic objectivity and situates image alteration within broader struggles over truth, authority, and power.

Early Photographic Intervention: Retouching and Removal, 1840s–1860s

The earliest decades of photography were marked by significant technical constraints that shaped both how images were produced and how they were altered. Long exposure times, unstable chemicals, and the sensitivity of early negatives made imperfections common. Dust, scratches, uneven lighting, and unintended figures routinely appeared in images. As a result, intervention was not initially framed as deception but as necessary correction, a way to bring the photograph closer to what the photographer believed the scene should have represented.

One of the earliest documented examples of deliberate photographic alteration occurred in 1846, when Calvert Richard Jones used India ink to blot out the image of a friar from a paper negative. The removal was not motivated by political intent but by compositional dissatisfaction. Yet the act is significant precisely because it demonstrates how quickly photographers realized that negatives were not sacrosanct objects. From the medium’s infancy, images were subject to revision, subtraction, and improvement at the hands of their makers.

Retouching soon became an accepted studio practice. Photographers routinely painted directly onto negatives to soften facial features, correct blemishes, or enhance contrast. Manuals and guides from the mid-nineteenth century openly discussed such techniques, treating them as part of professional skill rather than ethical compromise. Clients expected flattering likenesses, and photographers obliged, reinforcing the idea that photographs were not raw records but crafted representations.

These early interventions complicate later claims that photographic manipulation represents a fall from an original state of purity. In practice, photography never functioned as a passive recording device. The removal of unwanted elements, whether friars, shadows, or facial imperfections, reflected social expectations about order, clarity, and visual authority. Retouching and removal were foundational practices that established a precedent for treating photographs as mutable objects rather than immutable truths.

Combination Printing and the Construction of Authority

As photographic technology matured in the mid-to-late nineteenth century, photographers developed techniques that moved beyond simple retouching toward more ambitious forms of manipulation. One of the most influential of these was combination printing, a process in which multiple negatives were joined to produce a single composite image. This method allowed photographers to overcome technical limitations such as narrow depth of field and uneven exposure, but it also opened new possibilities for shaping meaning and authority within an image.

Combination printing was often justified as a practical solution to problems inherent in early photography. Landscapes could be rendered with properly exposed skies and foregrounds, and group portraits could be assembled from individually successful sittings. Yet these composites did more than correct deficiencies. They constructed scenes that had never existed as unified moments, presenting them as seamless visual realities. The resulting images carried the persuasive force of photography while quietly departing from photographic witness.

Portraiture proved especially fertile ground for this practice. In an era when photographic likeness increasingly shaped public perception, the demand for dignified, authoritative images was intense. One of the most famous examples is the composite image of Abraham Lincoln in which his head was placed onto the body of John C. Calhoun to create a more imposing and statesmanlike pose. Though widely circulated, the image reinforced Lincoln’s authority at a critical historical moment, demonstrating how photographic manipulation could serve political and symbolic ends without widespread public objection.

The acceptance of such composites reveals an important cultural logic. Manipulation was tolerated, even welcomed, when it aligned with existing expectations of leadership, virtue, and respectability. The photograph’s credibility was not undermined so long as it communicated a truth that viewers believed ought to be true. In this sense, authority was not simply recorded by photography but actively constructed through it.

Combination printing thus marked a pivotal shift in photographic practice. Images were no longer merely adjusted for clarity or beauty but engineered to convey power, stability, and legitimacy. The technique foreshadowed later political uses of photography by demonstrating that visual authority could be assembled as deliberately as it could be observed. The photograph’s claim to truth increasingly rested not on fidelity to a moment, but on its ability to persuade.

Spirit Photography, Double Exposure, and the Crisis of Belief

By the mid-nineteenth century, photography had acquired cultural authority that extended far beyond art or documentation. This authority made the medium especially potent when it intersected with spiritual belief. The rise of spirit photography in the 1860s occurred within a broader context of popular spiritualism, a movement that promised communication with the dead at a time marked by high mortality rates, religious uncertainty, and the social dislocation of industrial modernity. Photography, perceived as mechanically truthful, offered what séances alone could not: visual proof.

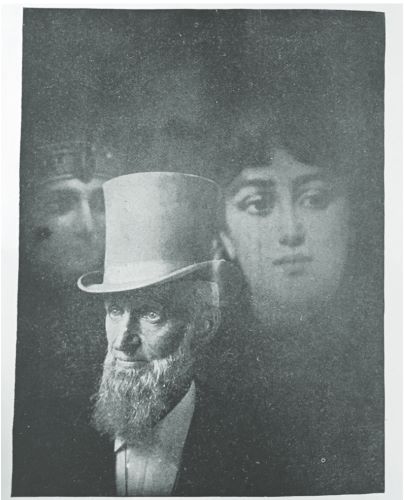

Spirit photographers exploited the technical possibilities of double exposure, a process by which two images were layered onto a single photographic plate. The resulting photographs depicted living subjects accompanied by faint, translucent figures identified as deceased relatives or spirits. To believers, these images confirmed the existence of an afterlife and validated deeply held emotional needs. To skeptics, they represented a misuse of photographic authority, leveraging the medium’s credibility to advance unverifiable claims.

William Mumler emerged as the most famous practitioner of spirit photography. His portraits, often featuring grieving clients with ghostly companions hovering nearby, gained wide circulation and considerable profit. Mumler insisted that he did not fabricate the images intentionally, attributing the apparitions to forces beyond his control. His claims, however, increasingly attracted scrutiny as similar “spirits” appeared across unrelated photographs, raising suspicions of deliberate manipulation.

The controversy culminated in Mumler’s 1869 fraud trial in New York. Prosecutors argued that the images were the product of photographic trickery rather than supernatural intervention, while defenders pointed to the limits of scientific understanding and the sincerity of believers. Although Mumler was acquitted due to insufficient evidence, the trial marked one of the earliest public confrontations between photography’s truth claims and its susceptibility to deception.

What made spirit photography uniquely destabilizing was not merely the presence of manipulation, but the role of belief in determining truth. The images functioned differently depending on the viewer’s expectations. For those inclined toward spiritualism, the photographs confirmed what they already believed. For skeptics, they illustrated how easily photography could be used to mislead. The medium itself did not resolve the dispute; interpretation did.

Spirit photography thus exposed a critical fault line in photographic culture. The camera’s authority depended less on its mechanical operation than on the trust invested in it by viewers. Once that trust was questioned, photography’s status as objective witness began to erode. The crisis provoked by spirit photography did not end belief in photographic truth, but it introduced enduring skepticism, demonstrating that photographs could persuade powerfully even when they misrepresented reality.

Photomontage as Art, Protest, and Political Weapon

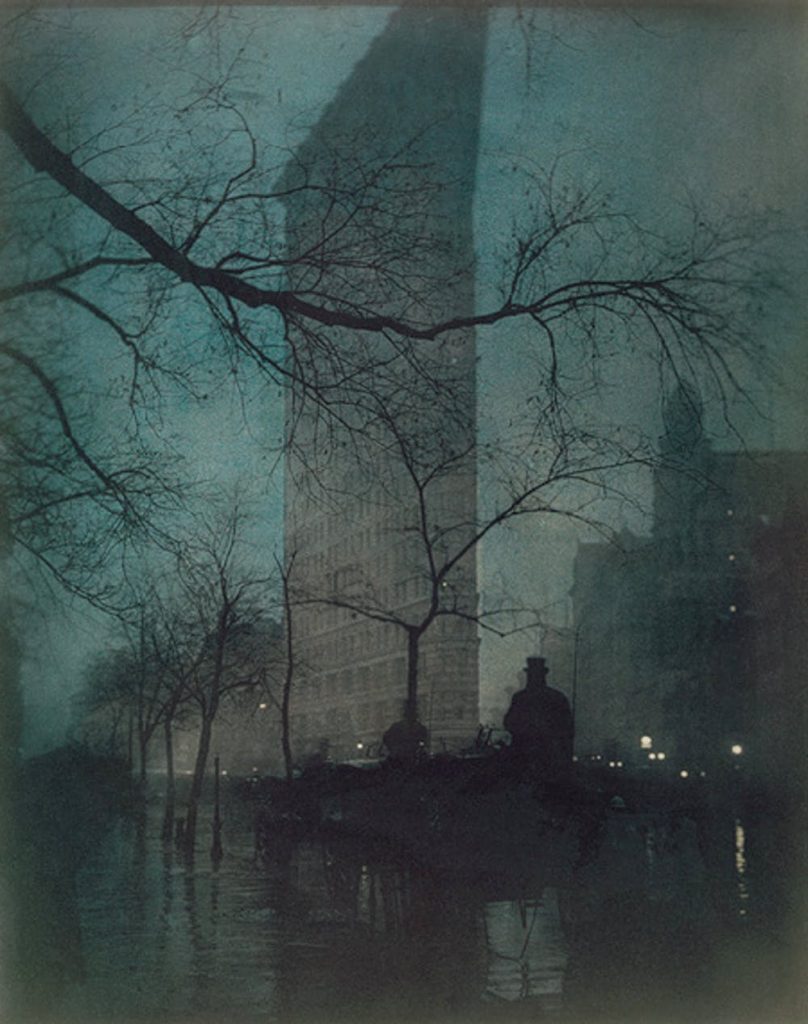

By the early twentieth century, photographic manipulation moved from concealment to declaration. Unlike retouching or combination printing, which sought to hide their interventions, photomontage foregrounded alteration as both method and message. Emerging most forcefully in the aftermath of the First World War, photomontage rejected photography’s claim to neutrality and instead treated images as materials to be cut, rearranged, and repurposed. In doing so, it exposed the constructed nature of visual meaning itself.

Artists associated with the Dada movement, particularly in Germany, were among the earliest and most influential practitioners of photomontage. Figures such as Hannah Höch, Raoul Hausmann, and John Heartfield used fragments of photographs drawn from newspapers, advertisements, and official imagery to create jarring compositions that mocked authority, nationalism, and bourgeois values. Their work did not attempt to deceive the viewer. On the contrary, its power lay in its obvious artificiality, forcing audiences to confront how images were already shaping political reality.

Photomontage quickly proved adaptable beyond avant-garde art circles. Political movements and governments recognized its potential as a tool of persuasion and agitation. By recombining familiar images in unfamiliar ways, photomontage could simplify complex ideas, exaggerate threats, and mobilize emotion. Unlike traditional propaganda painting, its photographic components retained the aura of reality, even as their recombination challenged conventional truth claims.

This shift marked an important conceptual break. Manipulation was no longer justified as technical correction or aesthetic improvement. It became an overt strategy for critique and control. Photomontage acknowledged that images were arguments, not records. Whether deployed by radical artists or state actors, it treated photography as a battlefield where meaning was contested rather than passively received.

The rise of photomontage underscored a growing awareness that visual authority could be manufactured as effectively through fragmentation as through seamless realism. By embracing manipulation openly, photomontage revealed the vulnerability of photographic truth to ideological use. It demonstrated that the power of images lay not in their fidelity to reality, but in their capacity to shape perception, align belief, and provoke response.

State Power and the Erasure of Persons: The Stalin Era

Nowhere was photographic manipulation more systematically harnessed to political power than in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. By the 1930s, photography had become an essential instrument of state authority, used to document achievements, glorify leadership, and construct an official narrative of revolutionary progress. At the same time, it served a more insidious function: the visual rewriting of history through the deliberate removal of individuals deemed politically dangerous or ideologically inconvenient.

Unlike earlier forms of photographic alteration motivated by aesthetics or belief, Soviet manipulation was explicitly bureaucratic and coercive. As officials fell from favor during purges, show trials, and internal power struggles, their images were physically excised from photographs that had once celebrated collective leadership. Group portraits were retouched, cropped, or entirely reissued, erasing former comrades as though they had never existed. These altered images were then redistributed as authoritative records, replacing earlier versions in archives, publications, and public displays.

The practice extended beyond mere image correction. It represented a coordinated effort to align visual memory with political orthodoxy. Photography, which had once promised permanence, was rendered provisional. Existence itself became contingent on continued ideological compliance. To disappear from photographs was to be symbolically unmade, reinforcing the regime’s claim to absolute control not only over bodies, but over history itself.

Airbrushing became the preferred technical method for these erasures, allowing photographers to smooth away figures while maintaining visual continuity. The resulting images often appeared unnaturally sparse or awkwardly composed, but their authority remained intact due to the centralized control of media. Alternative versions were suppressed, and public access to unaltered photographs was virtually nonexistent. The image archive thus functioned as a closed system, insulated from contradiction.

The consequences of this visual regime were profound. Photography no longer served even a pretense of documentation. It became an ideological instrument designed to normalize absence, to train viewers to accept disappearance as unremarkable. Over time, the repeated presentation of altered images reshaped collective memory, making it difficult to recall who had once stood beside whom, or even to imagine that the past might have looked different.

The Stalinist manipulation of photographs marks a critical moment in the history of visual truth. It demonstrated how easily the authority of photography could be subordinated to political power when control over archives, reproduction, and circulation was absolute. More broadly, it revealed the vulnerability of visual records in authoritarian systems, where images cease to preserve history and instead participate actively in its destruction.

Trust, Technology, and the Pre-Digital Precedent

By the early twentieth century, photographic manipulation was no longer novel, controversial, or hidden. It was an established practice operating across artistic, commercial, domestic, and political domains. What changed over time was not the existence of manipulation, but the cultural conditions under which photographs were trusted. Faith in images depended less on technological capability than on the social systems that governed their production, circulation, and interpretation.

Technological limitations are often cited as safeguards against deception in early photography, yet history demonstrates the opposite. Even with cumbersome equipment and chemical processes, photographers found ways to alter images when incentives existed. Manipulation thrived not because technology made it easy, but because audiences wanted photographs to confirm beliefs, reinforce authority, or preserve emotional narratives. Trust was conferred selectively, shaped by expectation rather than evidence.

The recurring pattern across the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is clear. When institutions controlled photographic circulation, as in authoritarian states, manipulation functioned as enforcement. When belief systems dominated interpretation, as with spirit photography, manipulation functioned as affirmation. When social conventions guided acceptance, as in portrait studios and composites, manipulation functioned as reassurance. In each case, the photograph’s authority derived from context, not accuracy.

This pre-digital precedent challenges the common assumption that visual deception is a uniquely modern problem. Long before pixels and algorithms, photographs were already persuasive instruments capable of misleading, comforting, or coercing. What mattered was not the sophistication of the tools, but the absence or presence of competing narratives, critical literacy, and archival transparency. Where skepticism was weak and alternatives inaccessible, manipulated images flourished.

Understanding this history reframes contemporary anxiety about image manipulation. The crisis of trust did not begin with digital technology. It is a recurring condition that emerges whenever images are granted authority without scrutiny. The lesson of the pre-digital era is not that manipulation was rare or crude, but that belief has always been the most powerful technology shaping how photographs are received and remembered.

Conclusion: When Images Become Arguments

Photography has never been a neutral witness to history. From its earliest decades, it functioned as a persuasive medium shaped by human intention, social expectation, and institutional power. Retouching, combination printing, spirit photography, photomontage, and state-directed erasure did not represent deviations from an otherwise objective practice. They revealed what photography had always been capable of doing: translating belief, authority, and ideology into visual form.

What unites these varied practices is not technical similarity but conceptual continuity. Each instance demonstrates how images operate as arguments about reality rather than transparent reflections of it. Whether smoothing imperfections, assembling authority, comforting the bereaved, mocking political power, or erasing inconvenient figures, manipulated photographs asked viewers to accept a particular version of the world. Their success depended less on concealment than on alignment with prevailing expectations and power structures.

This historical record challenges modern narratives that frame image manipulation as a crisis born of digital innovation. The anxiety surrounding contemporary visual technologies echoes earlier moments when photography’s authority was questioned and renegotiated. In every era, trust in images has been contingent, shaped by who controls production, how circulation is regulated, and whether audiences possess the tools to interpret images critically.

Understanding photography as a medium of argument rather than mere documentation restores historical clarity. Images do not simply record events. They participate in them. By recognizing the long history of photographic manipulation, viewers are better equipped to interrogate visual claims, resist passive consumption, and understand that the struggle over truth has always included the struggle over how reality is pictured.

Bibliography

- Ades, Dawn. Photomontage. London: Thames and Hudson, 1976.

- Batchen, Geoffrey. Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997.

- Boswell, Peter, Maria Makela, and Caryloyn Lanchner. The Photomontages of Hannah Höch. London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2014.

- —-. Each Wild Idea: Writing, Photography, History. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000.

- Braude, Ann. Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989.

- Bürger, Peter. Theory of the Avant-Garde. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

- Gernsheim, Helmut. Creative Photography: Aesthetic Trends, 1839–1960. New York: Dover Publications, 1962.

- —-. The Rise of Photography, 1850–1880: The Age of Collodion. London: Thames and Hudson, 1988.

- Gernsheim, Helmut, and Alison Gernsheim. The History of Photography from the Camera Obscura to the Beginning of the Modern Era. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1955.

- Gombrich, E. H. Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1960.

- Hannavy, John, ed. Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. New York: Routledge, 2007.

- Jones, Calvert Richard. “Talbotypes of the Holy Land.” 1846. In The Pencil of Nature, by William Henry Fox Talbot (Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans: 1844), related correspondence and early photographic experiments.

- King, David. The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia. New York: Metropolitan Books, 1997.

- Kotkin, Stephen. Stalin: Volume I: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928. New York: Penguin Press, 2014.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992.

- Nickell, Joe. Camera Clues: A Handbook for Photographic Investigation. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1994.

- Rosenblum, Naomi. A World History of Photography. 4th ed. New York: Abbeville Press, 2007.

- Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977.

- —-. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003.

- Tagg, John. The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

- Trachtenberg, Alan. Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Mathew Brady to Walker Evans. New York: Hill and Wang, 1989.

- Verdery, Katherine. The Political Lives of Dead Bodies: Reburial and Postsocialist Change. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

- Wollen, Peter. “Photography and Aesthetics.” Screen 19:4 (1978): 9-28.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.07.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.