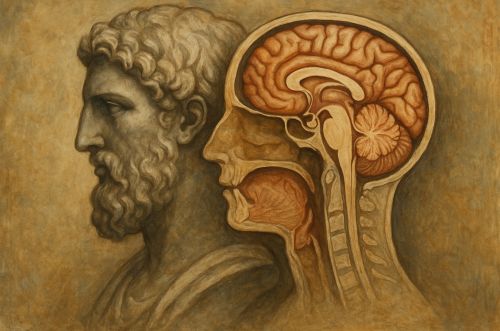

The ancient study of the brain was never purely scientific nor purely mystical. It arose from the effort to reconcile bodily observation with cultural beliefs about soul and self.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A Body of Questions

Human curiosity about the brain long predates the tools of modern neuroscience. Ancient peoples dissected skulls, observed head injuries, and theorized about sensation and thought. Their conclusions varied, shaped by cultural assumptions and philosophical systems, yet their observations often revealed striking insight.

What emerges across the civilizations of Egypt, Greece, Rome, India, and China is a complex history of competing ideas. The brain was at times dismissed as unimportant, at other times treated as the very seat of mind. These ancient debates did not merely anticipate modern neuroscience. They reflected how societies sought to understand the relationship between body, spirit, and cosmos. In their questions we glimpse the earliest efforts to map the frontier between physical substance and immaterial thought.

Egypt: The Forgotten Organ and the Papyrus of Knowledge

The Egyptians left us the oldest known medical reference to the brain in the Edwin Smith Papyrus. Dated to around 1600 BCE, it catalogues head wounds, noting symptoms such as speech loss and limb paralysis that correspond to modern neurological effects.1 It even describes cerebrospinal fluid, showing a close observational eye. The author, likely a physician-surgeon, recorded these cases with remarkable clinical precision.

Yet in ritual practice the Egyptians dismissed the brain as dispensable. During mummification, embalmers routinely discarded it, preserving the heart instead. For them the heart was the center of thought, memory, and soul. This contradiction illustrates the gap between practical observation and cultural worldview. Even when evidence suggested the brain’s importance, religious cosmology directed attention elsewhere. Such tension is characteristic of many ancient systems of knowledge.

Greece: Competing Philosophies of Mind

Greek thinkers placed the brain at the center of intellectual debate. Alcmaeon of Croton in the fifth century BCE argued that the brain governed sensation, reasoning that sensory channels connected directly to it.2 His views offered a physiological explanation of perception, linking anatomy to experience.

Hippocrates advanced the claim further. In On the Sacred Disease he attributed epilepsy to natural causes in the brain, rejecting the notion of divine punishment.3 This marked a radical step: mental illness was no longer framed purely as spiritual affliction but as a medical condition rooted in physical processes. His insights foreshadowed later scientific understandings of neurology.

Yet Aristotle steered Greek thought in another direction. He insisted the heart, not the brain, was the locus of intelligence. The brain, he argued, functioned as a cooling system for the blood.4 This theory, despite its inaccuracy, held sway for centuries because it aligned with cultural and philosophical traditions that privileged the heart as the seat of emotion and vitality. Greek thought on the brain thus vacillated between empiricism and metaphysics, producing a tension that shaped subsequent medical history.

Rome: Galen and the Anatomy of Authority

Roman inquiry reached a new level of sophistication with Galen, whose anatomical studies of animal brains became the foundation of Western medical thought for more than a millennium. Through dissection of apes, pigs, and oxen, Galen described the brain’s ventricles and identified it as the organ of sensation and movement.5 He theorized that “animal spirits” originated in the brain and traveled through the nerves, animating the body.

Galen’s authority rested not only on his empirical work but on his rhetorical skill. He positioned himself as both a careful observer and an interpreter of nature’s design. His writings were extensive, systematically linking anatomy with physiology. Though he made errors, particularly in extrapolating from animals to humans, his insistence on dissection and experimentation marked a decisive shift toward empirical study.

Roman attitudes, however, were not entirely uniform. While Galen’s framework dominated, skepticism persisted in philosophical circles. Some Romans remained attached to older notions of the heart’s primacy. The coexistence of competing views demonstrates that ancient science was not a straight path toward truth but a contested field where authority, culture, and observation intersected.

India: Consciousness and the Brain in Ayurveda

In India, Ayurvedic medicine recognized the brain (mastishka) but did not assign it sole authority over thought. Mental processes were understood through the balance of the three doshas, bodily energies that governed health and temperament.6 The heart and brain were linked as centers of consciousness, with emphasis on their interconnectedness rather than strict separation.

Texts such as the Charaka Samhita noted symptoms of brain injury and mental illness, yet these were interpreted through holistic frameworks. The brain was one site among many where bodily imbalance manifested. Ancient Indian medical theory thus approached the brain within a broader cosmological system, resisting the compartmentalization that characterized Greek and Roman traditions.

China: The “Sea of Marrow” and the Channels of Vitality

Chinese medicine similarly integrated the brain into a holistic vision of the body. The Huangdi Neijing described the brain as the “sea of marrow,” a reservoir that influenced sensory and motor functions.7 Yet the heart retained primacy as the center of mind and spirit (shen). The brain was important, but it functioned within a network of organs linked by channels of vital energy (qi).

This conception emphasized flow and balance rather than anatomical isolation. The brain was not studied in dissection but understood through its relationships with other organs and energies. As in India, neurological symptoms were interpreted as disruptions of harmony rather than localized damage. The conceptual framework diverged sharply from Greek anatomical models, yet it produced its own enduring medical system.

Conclusion: Between Flesh and Spirit

The ancient study of the brain was never purely scientific nor purely mystical. It arose from the effort to reconcile bodily observation with cultural beliefs about the soul, the self, and the cosmos. Egyptians noted neurological symptoms yet revered the heart. Greeks debated between observation and philosophy. Romans, under Galen, made anatomy central but did not silence older traditions. Indian and Chinese medicine wove the brain into holistic systems that emphasized balance rather than organ primacy.

What unites these traditions is the recognition that damage to the head could alter speech, sensation, or consciousness. That basic insight, that the material brain affects the immaterial mind, marked the beginning of a profound intellectual journey. Ancient peoples may not have mapped neurons or synapses, but they were already asking questions that remain with us: Where does thought reside? How does flesh produce consciousness? In their answers we find not superstition alone but the first steps toward the science of the mind.

Appendix

Footnotes

- James H. Breasted, trans., The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1930), 9–15.

- Heinrich von Staden, Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 58–62.

- Hippocrates, On the Sacred Disease, in Hippocratic Writings, trans. J. Chadwick and W. N. Mann (London: Penguin, 1978), 244–250.

- Aristotle, Parts of Animals, trans. William Ogle (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1912), 651–660.

- Galen, On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body, trans. M. T. May (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1968), 342–356.

- P. Kutumbiah, Ancient Indian Medicine (Bombay: Orient Longmans, 1962), 117–124.

- Paul U. Unschuld, Medicine in China: A History of Ideas (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 64–71.

Bibliography

- Aristotle. Parts of Animals. Translated by William Ogle. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1912.

- Breasted, James H., trans. The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1930.

- Galen. On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body. Translated by M. T. May. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1968.

- Hippocrates. On the Sacred Disease. In Hippocratic Writings. Translated by J. Chadwick and W. N. Mann. London: Penguin, 1978.

- Kutumbiah, P. Ancient Indian Medicine. Bombay: Orient Longmans, 1962.

- Unschuld, Paul U. Medicine in China: A History of Ideas. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

- von Staden, Heinrich. Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.19.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.