The persistence of racialized violence, economic exploitation, and social surveillance reveals that the crisis of policing is not episodic but constitutive.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In the mid-twentieth century, American law enforcement undertook a public relations experiment unprecedented in its scope and intent. Beginning in the 1960s, police departments across the United States launched the Officer Friendly program, a seemingly benign initiative in which uniformed officers visited elementary schools to present themselves as protectors, teachers, and neighborhood allies. They handed out coloring books and stickers, delivered lessons about safety, and invited children to see them not as agents of fear, but as approachable fixtures of civic virtue. The image was carefully designed: an unthreatening face of authority in an era when television screens were filled with images of police dogs, fire hoses, and riot gear turned against civil rights demonstrators. It was, in essence, a rebranding effort, a campaign to restore legitimacy to an institution increasingly viewed as an instrument of repression rather than justice.

Yet the Officer Friendly campaign, for all its genial optics, was not created in a vacuum. It emerged amid deep historical fault lines that had long defined the American policing project. Beneath the smiling faces and child-friendly curricula lay an unresolved contradiction: that policing itself had evolved not as a neutral guarantor of safety, but as a system entwined with social control, racial hierarchy, and economic discipline. From colonial slave patrols that hunted runaways and enforced white supremacy, to the industrial police forces that broke strikes and monitored immigrant neighborhoods, the authority of the badge was historically rooted in coercion. The public relations turn of the twentieth century, therefore, represented less a transformation than a crisis of legitimacy, a recognition that the old symbols of order no longer commanded the trust of the governed.

The decades between the 1960s and the 1980s saw an intensifying effort to soften that image through what departments called “community relations.” Officer Friendly was joined by a host of similar programs: open houses, neighborhood watch initiatives, and youth engagement campaigns. By the 1990s, these evolved into the broader framework of “community policing,” a reform philosophy advocating cooperation between citizens and officers to solve local problems. In policy rhetoric, it promised partnership, responsiveness, and human contact to replace distance and suspicion. But the optimism of this model concealed the limits of reform within the structure of policing itself. Bureaucratic incentives favored enforcement statistics over relationship-building, and police unions resisted accountability measures. The result was a partial transformation that never fully displaced the culture of command and control.

Today, a half-century after Officer Friendly first appeared in classrooms, the cycle has turned again. As public confidence in law enforcement has eroded following the repeated exposure of brutality, from Rodney King to George Floyd, departments have revived the logic of image management under new guises. Social media posts of officers dancing at block parties, rescuing kittens, or buying groceries for struggling families now circulate widely, a digital echo of those old coloring books. Critics have labeled this phenomenon “copaganda”: a strategy to humanize policing through spectacle rather than reform, diverting attention from systemic violence by emphasizing isolated acts of kindness. The imagery is more sophisticated, the platforms more immediate, but the underlying impulse remains the same—to repair legitimacy without altering power.

This essay examines that long historical arc: from the origins of American policing in the violence of slavery and industrial control, through the twentieth-century public relations projects that sought to cleanse its image, to the contemporary resurgence of branding as a substitute for structural reform. It argues that the persistence of distrust between police and communities of color cannot be understood apart from this lineage of representation and denial. Each phase of rebranding, from Officer Friendly to community policing to the viral posts of today, has sought to reconcile the irreconcilable, the coercive roots of an institution charged with maintaining a racialized social order and the democratic ideal of equal protection. The story is not merely about changing tactics, but about how a society remembers, forgets, and retells its relationship with authority.

Deep Roots: Slavery, Slave Patrols, and the Origins of Coercive Policing

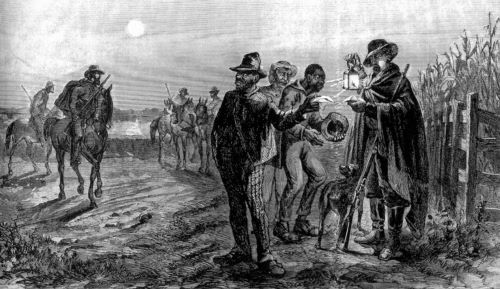

The mythology of policing in the United States often begins with the story of the “peace officer,” a figure charged with keeping order in a democratic society. But the historical record tells a different tale, one of coercion before community, and of control before law. In the American South, the earliest organized policing bodies were not civic guardians but slave patrols, established in the early eighteenth century to enforce racial hierarchy through violence and surveillance. The first formal patrols appeared in the Carolina colonies around 1704, operating under statutes that required white men to conduct nightly rides through plantations and roads, armed and authorized to stop, question, whip, or even kill enslaved Africans caught off-plantation without permission.1

These patrols were not marginal institutions. They were embedded in the legal and economic fabric of the South. Historian Sally E. Hadden’s comprehensive study Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas (2001) documents how patrol systems were codified by colonial assemblies and later state governments, giving them the force of law.2 They represented, in essence, the first tax-funded policing apparatus in what would become the United States. Their purpose was explicitly racial: to prevent rebellion, deter escape, and maintain the terror necessary to sustain slavery as a labor regime.3 As such, the patrol system institutionalized the surveillance of Black life as a matter of public policy, a precedent that would echo in postbellum “vagrancy” laws, Jim Crow policing, and twentieth-century stop-and-frisk practices.

When slavery ended, the patrols did not disappear. They evolved. In the Reconstruction South, former slave patrolmen often joined newly formed municipal police departments, carrying with them both tactics and ideology.4 The Black Codes, laws passed across the South beginning in 1865, criminalized minor infractions such as “loitering” or “vagrancy,” funneling freedmen into convict-leasing systems that restored forced labor under another name.5 Police were the enforcers of this new racial order, arresting Black citizens en masse to sustain the economic engine of the postwar South. The historian Douglas A. Blackmon describes this continuity in Slavery by Another Name (2008), showing how policing became the handmaiden of neo-slavery and racial capitalism.6 The lineage from patrol to police was thus not merely institutional but moral: both defined freedom as conditional, surveillance as normal, and punishment as natural.

In the North, policing followed a different trajectory but shared a common logic of control. The first organized municipal police department, established in Boston in 1838, was modeled after London’s Metropolitan Police.7 Yet the adaptation quickly took on distinctly American purposes. Industrialization and immigration produced dense working-class neighborhoods where elites saw disorder and danger. Urban police were tasked with regulating labor, suppressing strikes, and enforcing moral order in immigrant and Black communities.8 As historian Kristian Williams argues in Our Enemies in Blue (2004), “The police were created to manage the poor and working class, not to protect them.”9 This structural purpose, preserving property and authority, united Northern and Southern policing traditions despite their different origins.

By the turn of the twentieth century, reformers such as August Vollmer in Berkeley and Richard Sylvester in Washington, D.C., sought to professionalize policing by emphasizing discipline, education, and bureaucratic efficiency.10 They invoked scientific management and criminological expertise to distance modern policing from its brutal past. Yet professionalization did not mean neutrality. Vollmer’s “modern” model still reflected the assumptions of social hierarchy and racial order that had underpinned earlier systems.11 The emphasis on centralized command and patrol technology created distance between officers and communities, while the new criminological language pathologized poverty and racialized “deviance.”12

The emergence of so-called professional policing therefore represented not a clean break from coercion, but its rationalization. As Michelle Alexander later observed in The New Jim Crow (2010), “What has changed since the collapse of Jim Crow has less to do with the basic structure of racial control than with the language used to justify it.”13 The same might be said of early twentieth-century police reform: brutality was renamed efficiency, surveillance rebranded as science. The essential function, enforcing social order through selective application of law, remained intact.

The throughline from slave patrols to modern departments, then, is not a metaphor but a genealogy. The techniques of domination (curfews, checkpoints, patrols, and punitive labor) did not vanish; they were absorbed into the logic of statecraft. The cultural memory of this lineage persists in the collective distrust of police among Black Americans, a distrust born not of misunderstanding but of historical continuity. The “Officer Friendly” of the twentieth century would thus emerge to confront not an image problem alone, but a moral inheritance centuries in the making.

The Postwar Era and the Rise of Policing Public Relations (1950s–1960s)

By the middle of the twentieth century, American policing faced a crisis of legitimacy unprecedented in its modern history. The supposed “professionalization” of the early century had produced efficiency but not trust. Police remained overwhelmingly white, male, and insulated from the communities they patrolled. As cities swelled with African American migrants fleeing the Jim Crow South, the resulting demographic shifts were met with suspicion rather than inclusion. Policing became the visible edge of racial tension, an institution deployed to maintain “order” amid demands for justice. When television cameras captured Birmingham officers turning fire hoses and dogs on peaceful demonstrators in 1963, the nation’s moral conscience recoiled. What had been a local practice of brutality became an international embarrassment.14

In response, both federal and local agencies began to explore ways of humanizing law enforcement through what they called “community relations.” The strategy reflected the emerging discipline of public relations itself, an effort to manage perception through image, message, and controlled visibility. The Officer Friendly program was the most emblematic expression of this shift. Developed by the Chicago Police Department in 1966 in collaboration with the Sears-Roebuck Foundation, the program sought to reshape the police’s reputation by cultivating trust among the youngest members of society.15 Uniformed officers visited elementary schools, distributed coloring books and safety pamphlets, and emphasized cooperation rather than punishment. In its early press materials, the program promised to “replace fear with friendship,” presenting police as benevolent neighbors rather than enforcers.16

The sociological logic was straightforward: if children learned to view police as protectors, that perception would ripple outward to families and future generations. But the initiative also reflected a calculated response to the upheavals of the 1960s. Civil rights protests, anti-war demonstrations, and urban uprisings had exposed a widening gulf between the police and the policed. In 1967, the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice released its report The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society, which warned that “police–community relations are in serious disrepair” and recommended education-based trust-building measures.17 Many departments across the country took this as a cue to launch school outreach programs, safety fairs, and neighborhood meetings, all designed to produce a more palatable public image.

Yet the friendly facade could not conceal the contradiction at the heart of policing. While officers handed out coloring books in classrooms, others were enforcing stop-and-frisk ordinances and dispersing antiwar marches with batons and tear gas. Black newspapers such as The Chicago Defender and The Amsterdam News viewed these programs skeptically, often describing them as attempts to pacify criticism rather than confront structural injustice.18 Sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois had long warned that the police served as “the visible government of the poor,” and the Officer Friendly campaign did little to change that reality.19 It functioned less as reform than as reputation management, what historian Stuart Schrader later called “policing the crisis of policing.”20

The campaign’s spread was rapid. By the early 1970s, Officer Friendly programs existed in more than two dozen major metropolitan areas.21 Police departments partnered with school districts, civic clubs, and private sponsors to distribute millions of pieces of branded material including comic strips, safety videos, and even dolls. The figure of the smiling, approachable officer became an icon of midcentury optimism, a kind of moral marketing intended to sanitize the uniform. But evidence of impact was elusive. Surveys conducted by the U.S. Department of Justice in the late 1970s found no measurable change in adult perceptions of police legitimacy in cities with active programs.22 The goodwill campaign simply did not reach those most affected by police violence, adults in Black and poor neighborhoods who encountered law enforcement not in classrooms but in alleyways and traffic stops.

Still, the cultural impact of Officer Friendly endured. For a generation of suburban white children, the program reinforced a vision of the police as benevolent authority. Popular media, from children’s books to television dramas, amplified this image. The friendly patrolman became a trope in shows such as Dragnet and Adam-12, both produced with technical assistance from the Los Angeles Police Department.23 As historian Christopher Wilson observes, these portrayals “worked to naturalize police authority by linking it to moral instruction and civic education.”24 By the time the riots of the late 1960s and early 1970s broke out in Newark, Detroit, and Los Angeles, television audiences were already primed to interpret them through a moral lens: the good cop under siege by chaos.

Beneath the surface of this PR revolution, however, lay an institutional unease. Policing had become a contested symbol of state legitimacy during an age of civil disobedience and social reform. The Officer Friendly model was never intended to change policing practices; it was designed to change perception. In this sense, it marked the birth of “copaganda,” the strategic production of friendly images to preserve the authority of a violent institution. It was not the end of coercion, but its camouflage. The following decades would see this approach evolve into the more sophisticated language of “community policing,” a reform movement that promised cooperation but often delivered only a softer vocabulary for the same structural control.

From Reactive Policing to Community Policing: Reform in the 1970s–1990s

The 1970s opened with a paradox. After nearly a decade of public relations efforts, surveys still showed deep public mistrust of police, especially among African Americans, Latinos, and young people. The Officer Friendly era had softened the rhetoric but not the reality. The same decade that produced coloring books also produced images of police officers in riot helmets at Kent State and Attica. The dissonance between public messaging and street-level enforcement made clear that goodwill campaigns could not substitute for institutional reform. What emerged instead was the language of “community policing,” a philosophy that promised to transform both the tactics and spirit of law enforcement.

The intellectual roots of community policing lay partly in disillusionment with the technocratic model that had dominated mid-century policing. That model, built on centralization, rapid response, and motorized patrols, was premised on deterrence through omnipresence. Yet the Kansas City Preventive Patrol Experiment (1972–73) shattered that assumption, showing that random patrols had virtually no effect on crime rates or public fear.25 The report concluded that “police presence, in and of itself, does not constitute police effectiveness.”26 For reform-minded administrators, this finding was seismic. It suggested that the police could no longer justify their legitimacy through visibility alone, they had to engage directly with the communities they served.

At the same time, the social upheavals of the late 1960s had left a residue of suspicion and hostility. The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (the Kerner Commission) had warned in 1968 that “the abrasive relationship between the police and the minority community is a major source of tension.”27 The Commission urged departments to hire more minority officers, emphasize community consultation, and create grievance mechanisms for misconduct. In practice, however, most agencies resisted substantive change. Only under the twin pressures of federal funding and political crisis did reform begin to move from rhetoric to policy.

The concept of community policing gained traction in the late 1970s through both academic theory and federal initiatives. Herman Goldstein’s landmark essay “Problem-Oriented Policing” (1979) challenged departments to focus on underlying causes of recurring problems rather than reacting to incidents.28 Goldstein’s model proposed that police identify specific community concerns (abandoned buildings, domestic disputes, noise complaints) and work collaboratively to address them before they escalated into crimes. The approach was preventive rather than reactive, relational rather than procedural. Simultaneously, James Q. Wilson and George Kelling’s “Broken Windows” theory (1982) posited that minor disorder, if left unchecked, created an environment that encouraged more serious crime.29 Though the two ideas differed in tone (Goldstein’s was cooperative, Kelling’s punitive) they both reframed police legitimacy as contingent on neighborhood perception.

In practice, the movement toward community policing coincided with the political realignment of the Reagan era. The federal government’s Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA), established under Lyndon Johnson’s 1968 Safe Streets Act, had laid the groundwork for federal support of policing innovation.30 But by the early 1980s, federal funding for social programs declined while funds for law enforcement grew. This created a paradoxical climate: community policing was promoted as a progressive reform even as mass incarceration accelerated.31 Cities adopted the rhetoric of partnership while simultaneously embracing aggressive tactics against drugs and “urban blight.” The duality was perhaps most evident in New York City, where community policing units coexisted uneasily with “stop, question, and frisk” policies.32

Despite this tension, community policing continued to gain bureaucratic legitimacy. In 1994, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act created the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS), distributing over $14 billion in federal grants to support hiring and training initiatives.33 This represented the institutionalization of what had begun as an experimental philosophy. Cities such as Chicago, Seattle, and Houston launched high-profile community policing projects. The Chicago Alternative Policing Strategy (CAPS), initiated in 1993, became one of the most studied examples.34 It divided the city into 279 “beats,” each with its own regular community meetings between residents and officers. Early evaluations suggested modest improvements in satisfaction and perception of responsiveness, though not in measurable reductions in crime.35

Yet even as community policing became the dominant paradigm in law enforcement policy, it remained conceptually ambiguous. Critics pointed out that “community” itself was a contested term, who defined it, and whose interests it served, varied from one neighborhood to another.36 The reform depended heavily on officer discretion and departmental culture, both of which often reproduced the very hierarchies it sought to dismantle.37 Furthermore, the performance metrics used to assess policing still privileged quantifiable outcomes (arrests, citations, response times) over the qualitative dimensions of trust and engagement.38 The underlying institutional logic of enforcement thus persisted beneath the vocabulary of partnership.

By the late 1990s, many of the same cities that had championed community policing began to pivot toward data-driven strategies such as COMPSTAT, first introduced in New York City under Police Commissioner William Bratton.39 COMPSTAT’s emphasis on statistical accountability re-centralized decision-making, reasserting the managerial model that community policing had sought to decentralize.40 The reform cycle had come full circle: the police had once again become data managers rather than neighbors, technocrats rather than partners. The rhetoric of community remained, but the relational substance evaporated into spreadsheets and performance charts.

Community policing, then, represents both an aspiration and a cautionary tale. It demonstrated that the desire for legitimacy could produce genuine innovation (officers walking beats, residents co-designing safety initiatives) but also that without structural change, even the most progressive rhetoric risks becoming another layer of branding. The spirit of Officer Friendly persisted, reframed in bureaucratic language, promising reform while leaving untouched the deeper architecture of power that policing continued to serve.

The Waning of the “Friendly” Era and the Rise of Copaganda (2000s–Present)

By the early 2000s, the language of “community policing” had become institutional orthodoxy, appearing in nearly every major department’s mission statement. Yet even as the term persisted, its practice diminished. The post-9/11 turn toward national security reoriented policing around counterterrorism, surveillance, and militarization. Homeland Security grants flooded local agencies with armored vehicles, assault weapons, and tactical gear.41 The police officer who had once been reimagined as a neighborhood partner was now cast as a domestic soldier. Patrol cars bore American flag decals; recruitment videos showcased special-operations units rappelling from helicopters.42 The community had become a potential threat, and visibility, once the mark of transparency, now signaled tactical dominance.

The logic of “approachability” did not disappear, however. It simply adapted to a new media ecology. Departments increasingly turned to public relations as a form of digital counterinsurgency using social media to project warmth, humor, and benevolence while maintaining coercive power offline.43 The Los Angeles Police Department’s “Tweet-Along” events invited users to ride virtually with patrol officers via live updates, blending spectacle with simulation. The New York Police Department’s “Good Deed of the Day” posts featured smiling officers buying lunch for the homeless or rescuing animals. Even small-town agencies began producing viral videos of officers dancing, lip-syncing, or performing TikTok skits.44 The rhetoric of Officer Friendly had found its twenty-first-century platform, short-form content calibrated for algorithmic reach.

This phenomenon, often termed copaganda, operates as both propaganda and cultural inoculation. The term entered academic and journalistic discourse in the 2010s to describe the systematic circulation of pro-police imagery across entertainment and social media.45 Cultural theorists trace its roots to the “cop show” boom of the late twentieth century, when programs such as Law & Order, COPS, and Blue Bloods constructed narratives of moral certainty in which the police embodied civilization itself.46 But in the digital age, departments became their own production studios. Public information offices employed content strategists, videographers, and social-media managers. Departments like Houston, Dallas, and Boston maintained multi-platform campaigns featuring mascots, holiday PSAs, and “feel-good” footage of officers interacting with children.47 The message was consistent: the police were not an occupying force but a family member in uniform.

The political context, however, revealed a more ambivalent reality. Even as copaganda flooded screens, public scrutiny of policing intensified after a series of high-profile killings: Amadou Diallo (1999), Sean Bell (2006), Oscar Grant (2009), Michael Brown (2014), Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd (2020). Each case sparked waves of protest and reform rhetoric, yet the institutional response often centered on narrative control rather than structural change.48 Body-worn cameras, initially heralded as tools of transparency, quickly became instruments of selective visibility: departments released footage strategically to reinforce official accounts while withholding recordings that contradicted them.49 The camera, like the coloring book before it, became a tool not of accountability but of image management.

Scholars such as Mathieu Deflem and Victor Kappeler argue that this period marks the full convergence of policing and marketing.50 Departments adopted “brand management” frameworks derived from corporate communication, emphasizing public engagement metrics over civil-rights benchmarks. Public trust became a quantifiable outcome measured through online sentiment rather than lived experience. The logic was circular: good publicity signified legitimacy, and legitimacy justified continued funding. As journalist Alicia Garza observed, “police learned to tell better stories about themselves faster than we learned to stop believing them.”51

Yet despite its ubiquity, copaganda has not erased skepticism, it has polarized it. Studies by the Pew Research Center show that while trust in police remains relatively high among white Americans, it has declined sharply among Black and Latino respondents since 2014.52 The divergence suggests that public relations strategies cannot overcome histories of violence and inequality. In communities where the police presence is felt primarily through surveillance, searches, and stops, online friendliness reads as dissonance, even mockery. The gap between representation and reality, once papered over by the charm of Officer Friendly, now unfolds in real time across viral feeds.

At the same time, some reform efforts have continued to invoke the principles of community policing, albeit in fragmented form. Departments in New Haven, Camden, and Denver experimented with hybrid models emphasizing non-enforcement engagement, mental-health response units, and civilian partnership boards.53 Evaluations indicate that even brief positive interactions can modestly improve public attitudes toward officers, but only when reinforced by consistent institutional behavior.54 In most jurisdictions, budget priorities and political incentives continue to favor enforcement over engagement. The performative remains cheaper than the structural.

Thus, the twenty-first century has seen not the death of Officer Friendly, but his reincarnation in pixels. Copaganda offers the same promise, humanity without accountability, trust without transformation. It functions as a cultural balm for the discomfort of inequality, reassuring audiences that the system can smile. The friendly officer still waves, but now through a screen, algorithmically optimized for affirmation. The historical cycle continues: each generation rebuilds the myth of benevolence atop the ruins of its predecessors, forgetting that what needs reform is not the image of policing, but its foundation.

Analytical Themes and Tensions

To trace the history of American policing from slave patrols to Officer Friendly to copaganda is to chart the evolution of an institution perpetually remaking its image to preserve its authority. Across three centuries, reform has largely been rhetorical, a language of renewal that rarely penetrates the deeper architecture of power. Beneath the changing lexicon, from “patrol” to “professionalism” and “community relations” to “problem-oriented policing,” the essential function has persisted: to manage social order through control, surveillance, and selective enforcement. The crisis has never been one of communication but of structure.

The first recurring theme is the disjunction between image and institution. Policing’s self-presentation has long outpaced its willingness to change. The Officer Friendly program, for example, sought to humanize law enforcement during a decade of civil unrest without altering its disciplinary practices. Likewise, twenty-first-century social media campaigns present acts of kindness as evidence of reform, though these moments occur within systems that remain resistant to transparency and accountability. Sociologist Alex S. Vitale argues that such gestures amount to “legitimacy work,” an ongoing effort to secure consent for practices of coercion.55 The smile, in this sense, functions as strategy, a symbolic balm for wounds never treated.

The second tension lies in the commodification of trust. As departments adopted managerial and marketing frameworks, legitimacy became a measurable asset. Surveys, sentiment analytics, and brand monitoring replaced substantive engagement as indicators of success.56 Community policing was once conceived as a relational practice; it has since become a bureaucratic performance. The “community” invoked in police reports and funding proposals often bears little resemblance to the fractured neighborhoods subjected to policing itself. As David Garland observed in his work on the culture of control, institutions adapt to crisis by redefining success, not by transforming purpose.57

A third theme concerns the continuity of racialized governance. Despite the rhetoric of neutrality, the geography of policing still mirrors the geography of inequality. Data from the Department of Justice’s Ferguson Report (2015) revealed that municipal policing and fine structures in many American cities disproportionately target Black residents, reproducing the logics of extraction first institutionalized in slave patrols and later in convict leasing.58 Reform discourse often abstracts from this reality, treating mistrust as a matter of perception rather than historical memory. Yet the continuity is empirical as well as symbolic: the mechanisms of control (curfew, patrol, discretionary stop) have persisted under successive euphemisms. As historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad notes, “the criminalization of Blackness was not an accident of policy but its central premise.”59

Finally, there is the problem of historical amnesia. Each generation of reformers tends to present its innovations as unprecedented, forgetting prior attempts and their failures. This absence of institutional memory allows the same ideas to be repackaged under new names: Officer Friendly becomes “neighborhood policing”; “public relations” becomes “transparency.” In forgetting, policing preserves its power to reinvent itself without reckoning with its past.60 The result is an endless cycle of reform and relapse, a process of rebranding that sustains legitimacy without delivering justice.

Conclusion

The evolution of American policing is not a story of linear progress, but of recursive adaptation. The Officer Friendly of the 1960s was not born from innocence but from crisis, a response to the visible brutality of an institution that could no longer sustain its legitimacy through force alone. Community policing in the 1980s and 1990s sought to professionalize friendliness, embedding it in policy while leaving enforcement hierarchies intact. Copaganda in the 2000s and beyond digitized that same impulse, transforming goodwill into content and trust into a metric. Across these eras, the central challenge has remained constant: how to reconcile an institution designed for control with a society that demands justice.

History suggests that surface reform cannot cure structural contradiction. A police force rooted in inequality cannot rebrand itself into legitimacy; it must reckon with its foundation. The persistence of racialized violence, economic exploitation, and social surveillance reveals that the crisis of policing is not episodic but constitutive. What the Officer Friendly campaign attempted to obscure, the moral dissonance between service and domination, remains the defining tension of modern law enforcement.

To remember this history is not to reject the ideal of public safety, but to redefine it. True community safety cannot be built through charm or image management, nor through algorithmic friendliness. It requires dismantling the conditions that make coercion appear necessary: poverty, segregation, and fear. Until those structures change, the police will continue to oscillate between force and friendliness, apology and performance, forever chasing legitimacy through aesthetics. The lesson of this history is clear: policing’s crisis of trust cannot be solved by changing how it looks, but only by changing what it is.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Sally E. Hadden, Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 34–38.

- Ibid., 57–62.

- Kristian Williams, Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America (Cambridge: South End Press, 2004), 15–21.

- Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Anchor Books, 2008), 42–49.

- Ibid., 61–67.

- Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name, 102–105.

- Gary T. Marx, “Police and the Myth of Professionalism,” in The Police and Society: Touchstone Readings, ed. Victor Kappeler (Long Grove: Waveland Press, 2006), 10–12.

- Robert M. Fogelson, Big-City Police (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1977), 22–28.

- Williams, Our Enemies in Blue, 19.

- Samuel Walker, A Critical History of Police Reform: The Emergence of Professionalism (Lexington: Lexington Books, 1977), 73–80.

- Alex S. Vitale, The End of Policing (London: Verso, 2017), 23–29.

- Fogelson, Big-City Police, 37–41.

- Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2010), 2.

- Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016), 42–48.

- Stacy Ann Lewis, “A History of Programs Implemented by the Chicago Police Department within Chicago Public Schools,” Dissertations, Loyola eCommons 50 (2011).

- Ebony Staff, “Whatever Happened to ‘Officer Friendy?’” Ebony (August 12, 2016).

- President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1967), 91–92.

- James Wilson.

- W.E.B. Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1899), 382.

- Stuart Schrader, Badges Without Borders: How Global Counterinsurgency Transformed American Policing (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019), 101–106.

- James Wilson.

- U.S. Department of Justice, Police-Community Relations Programs: A Review of Practices (Washington, D.C.: LEAA, 1978), 23–26.

- James Wilson.

- Christopher Wilson, Cop Knowledge: Police Power and Cultural Narrative in Twentieth-Century America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 147–152.

- George L. Kelling et al., The Kansas City Preventive Patrol Experiment: A Summary Report (Washington, D.C.: Police Foundation, 1974), 7–12.

- Ibid., 18.

- National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968), 299.

- Herman Goldstein, “Improving Policing: A Problem-Oriented Approach,” Crime & Delinquency 25, no. 2 (1979): 236–258.

- James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling, “Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety,” The Atlantic Monthly, March 1982, 29–38.

- Lyndon B. Johnson, “Message to Congress on Crime and Law Enforcement,” March 9, 1966, Public Papers of the Presidents.

- Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime, 182–187.

- Jeffrey Fagan, Franklin E. Zimring, and June Kim, “Declining Homicide in New York City: A Tale of Two Trends,” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 88, no. 4 (1998): 1277–1323.

- U.S. Department of Justice, Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) Fact Sheet (Washington, D.C.: DOJ, 1994).

- Wesley G. Skogan and Susan M. Hartnett, Community Policing, Chicago Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 3–7.

- Wesley G. Skogan, Evaluation of Chicago’s Alternative Policing Strategy (Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Justice, 2000), 11–15.

- Dennis P. Rosenbaum, “The Challenge of Community Policing: Testing the Promises,” in The Challenge of Community Policing, ed. Dennis P. Rosenbaum (Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1994), 4–5.

- Michael D. Reisig, “Community and Problem-Oriented Policing,” Crime & Justice 39, no. 1 (2010): 1–53.

- Peter K. Manning, Police Work: The Social Organization of Policing (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1977), 112–116.

- Eli B. Silverman, NYPD Battles Crime: Innovative Strategies in Policing (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1999), 43–47.

- John E. Eck and Edward R. Maguire, “Have Changes in Policing Reduced Violent Crime? An Assessment of the Evidence,” in The Crime Drop in America, ed. Alfred Blumstein and Joel Wallman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 229–233.

- Radley Balko, Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces (New York: PublicAffairs, 2013), 204–210.

- Peter B. Kraska and Victor E. Kappeler, “Militarizing American Police: The Rise and Normalization of Paramilitary Units,” Social Problems 44, no. 1 (1997): 1–18.

- Ben Bradford and Jonathan Jackson, “Cooperating with the Police: Social Control and the Reproduction of Police Legitimacy,” SSRN Electronic Journal (July 2010).

- Holson, Laura M., “Police Officers Lip-Sync as Part of Public Relations Dance,” New York Times, July 23, 2018, Arts section.

- David Correia and Tyler Wall, Police: A Field Guide (London: Verso, 2018), 69–74.

- Megan Garber, “#TheDress and the Rise of Attention-Policing,” The Atlantic, February 27, 2015.

- NYCLU. “What is Copaganda, and How do We Fight It?” ACLU of New York, July 3, 2025.

- Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016), 47–56.

- Bryce Clayton Newell, Police on Camera: Surveillance, Privacy, and Accountability, London: Routledge, 2021.

- Deflem, Mathieu. The Politics of Policing: Between Force and Legitimacy. New York: Emerald Publishing Limited, 2016.

- Alicia Garza, The Purpose of Power: How We Come Together When We Fall Apart. New York: One World, 2020.

- Pew Research Center, “Deep Racial and Partisan Divisions in Views of the Police,” August 2020.

- David A. Harris, “Reimagining Public Safety: The Camden and Denver Experiments,” American Journal of Criminal Law 48, no. 3 (2021): 275–305.

- Kyle Peyton, Michael Sierra-Arévalo, and David G. Rand, “A Field Experiment on Community Policing and Police Legitimacy,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, no. 40 (2019): 19894–19898.

- Alex S. Vitale, The End of Policing (London: Verso, 2017), 17–23.

- Deflem, 104.

- David Garland, The Culture of Control: Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 42–45.

- U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department (Washington, D.C.: DOJ, 2015), 3–5.

- Khalil Gibran Muhammad, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 8–9.

- Stuart Hall et al., Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order (London: Macmillan, 1978), 215–220.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press, 2010.

- Balko, Radley. Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces. New York: PublicAffairs, 2013.

- Blackmon, Douglas A. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York: Anchor Books, 2008.

- Bradford, Ben and Jonathan Jackson. “Cooperating with the Police: Social Control and the Reproduction of Police Legitimacy.” SSRN Electronic Journal (July 2010).

- Correia, David, and Tyler Wall. Police: A Field Guide. London: Verso, 2018.

- Deflem, Mathieu. The Politics of Policing: Between Force and Legitimacy. New York: Emerald Publishing Limited, 2016.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1899.

- Eck, John E., and Edward R. Maguire. “Have Changes in Policing Reduced Violent Crime? An Assessment of the Evidence.” In The Crime Drop in America, edited by Alfred Blumstein and Joel Wallman, 207–265. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Ebony Staff. “Whatever Happened to ‘Officer Friendy?’” Ebony (August 12, 2016).

- Fagan, Jeffrey, Franklin E. Zimring, and June Kim. “Declining Homicide in New York City: A Tale of Two Trends.” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 88, no. 4 (1998): 1277–1323.

- Fogelson, Robert M. Big-City Police. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1977.

- Garber, Megan. “#TheDress and the Rise of Attention-Policing.” The Atlantic, February 27. 2015.

- Garland, David. The Culture of Control: Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

- Garza, Alicia. The Purpose of Power: How We Come Together When We Fall Apart. New York: One World, 2020.

- Goldstein, Herman. “Improving Policing: A Problem-Oriented Approach.” Crime & Delinquency 25, no. 2 (1979): 236–258.

- Hall, Stuart, Chas Critcher, Tony Jefferson, John Clarke, and Brian Roberts. Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order. London: Macmillan, 1978.

- Hadden, Sally E. Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Hasbrouck, Brandon. “Reimagining Public Safety,” Northwestern University Law Review 117, no. 3 (2022): 685-730.

- Hinton, Elizabeth. From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Holson, Laura M. “Police Officers Lip-Sync as Part of Public Relations Dance.” New York Times, July 23, 2018, Arts section.

- Johnson, Lyndon B. “Message to Congress on Crime and Law Enforcement.” March 9, 1966. Public Papers of the Presidents.

- Kelling, George L., Anthony Pate, Duane Dieckman, and Charles E. Brown. The Kansas City Preventive Patrol Experiment: A Summary Report. Washington, D.C.: Police Foundation, 1974.

- Kelling, George L., and James Q. Wilson. “Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety.” The Atlantic Monthly, March 1982, 29–38.

- Kraska, Peter B., and Victor E. Kappeler. “Militarizing American Police: The Rise and Normalization of Paramilitary Units.” Social Problems 44, no. 1 (1997): 1–18.

- Lewis, Stacy Ann. “A History of Programs Implemented by the Chicago Police Department within Chicago Public Schools.” Dissertations, Loyola eCommons 50 (2011).

- Manning, Peter K. Police Work: The Social Organization of Policing. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1977.

- Marx, Gary T. “Police and the Myth of Professionalism.” In The Police and Society: Touchstone Readings, edited by Victor Kappeler, 1–24. Long Grove: Waveland Press, 2006.

- Muhammad, Khalil Gibran. The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968.

- Newell, Bryce Clayton. Police on Camera: Surveillance, Privacy, and Accountability. London: Routledge, 2021.

- NYCLU. “What is Copaganda, and How do We Fight It?” ACLU of New York, July 3, 2025.

- Pew Research Center. “Deep Racial and Partisan Divisions in Views of the Police.” August 2020.

- Peyton, Kyle, Michael Sierra-Arévalo, and David G. Rand. “A Field Experiment on Community Policing and Police Legitimacy.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, no. 40 (2019): 19894–19898.

- President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice. The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1967.

- Reisig, Michael D. “Community and Problem-Oriented Policing.” Crime & Justice 39, no. 1 (2010): 1–53.

- Rosenbaum, Dennis P. “The Challenge of Community Policing: Testing the Promises.” In The Challenge of Community Policing, edited by Dennis P. Rosenbaum, 3–10. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1994.

- Schrader, Stuart. Badges Without Borders: How Global Counterinsurgency Transformed American Policing. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019.

- Silverman, Eli B. NYPD Battles Crime: Innovative Strategies in Policing. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1999.

- Skogan, Wesley G. Evaluation of Chicago’s Alternative Policing Strategy. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Justice, 2000.

- Skogan, Wesley G., and Susan M. Hartnett. Community Policing, Chicago Style. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016.

- U.S. Department of Justice. Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) Fact Sheet. Washington, D.C.: DOJ, 1994.

- ———. Police-Community Relations Programs: A Review of Practices. Washington, D.C.: LEAA, 1978.

- U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division. Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department. Washington, D.C.: DOJ, 2015.

- Vitale, Alex S. The End of Policing. London: Verso, 2017.

- Walker, Samuel. A Critical History of Police Reform: The Emergence of Professionalism. Lexington: Lexington Books, 1977.

- Williams, Kristian. Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America. Cambridge: South End Press, 2004.

- Wilson, Christopher. Cop Knowledge: Police Power and Cultural Narrative in Twentieth-Century America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

- Wilson, James Q., and George L. Kelling. “Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety.” The Atlantic Monthly, March 1982.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.08.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.