Through its representation of physical and psychological effects, Séjour’s story inaugurated the literary delineation of slavery’s submission-rebellion binary.

By Dr. Ed Piacentino

Professor Emeritus of English

High Point University

Overview

This essay examines Victor Séjour’s “The Mulatto” (1837), a short story acknowledged as the first fictional work by an African American. Through its representation of physical and psychological effects, Séjour’s story, a narrative of slavery in Saint-Domingue, also inaugurated the literary delineation of slavery’s submission-rebellion binary. The enslaved raconteur in “The Mulatto” voices protest and appeals to social consciousness and sympathy, anticipating the embedded narrators in works of later writers throughout the Plantation Americas.

Introduction

A little-known story first translated into English in 1995 by Philip Barnard for The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, “Le Mulâtre” (“The Mulatto”) by Victor Séjour (1817–1874), a New Orleans free man of color, was initially published in the March 1837 issue of Cyrille Bisette‘s Parisian abolitionist journal La Revue des Colonies. La Revue was a monthly periodical of “Colonial Politics, Administration, Justice, Education and Customs” owned and sponsored by a “society of men of color.” A recent immigrant to Paris, Séjour was in an amenable environment among kindred spirits who shared his sentiments about slavery.

La Revue‘s cover, according to Charles E. O’Neill, Séjour’s biographer, features a “black slave in chains, with palms and waterfall in the background; kneeling on one knee, hands clasped in petition [and] ask[ing] ‘Am I not a man and your brother?'” This illustration accentuates the journal’s anti-slavery intent: to expose the “dissatisfaction with the slow, evasive parliamentary handling of poverty and oppression in the colonies” (O’Neill 14). In this iconic image, the slave expresses his humanity although secured by chains and kneeling in supplication.[1] The slave proffers a plea for personhood and liberation that evokes the plight of the enslaved throughout the Plantation Americas, a zone, as George Handley notes, “of perplexing but compelling commonality among Caribbean nations, the Caribbean coasts of Central and South America and Brazil, and the US South….” (Handley 25).

As a native of New Orleans and resident of the French Quarter, Séjour spoke French, attended private school, and was free but not white. When Séjour resided in New Orleans, free persons of color (gens de couleur) were numerous and did not enjoy political rights equal to those of whites (O’Neill 1). At nineteen, Séjour became an expatriate by choice, moving to Paris to continue his education and find work, and eventually joining forces with Cyrille Bisette, publisher of La Revue, and other members of the Parisian literary elite who helped him to start a formal writing career. In Paris, Séjour, a colonial mulatto, found a more open-minded milieu with less racial prejudice where he could exercise liberties not allowed in antebellum New Orleans. In 1837, a black man living in the United States could not have published as stark and haunting an antislavery revenge narrative as “The Mulatto.” With this publication, the first African-American fictional narrative and the first of Séjour’s works to appear in print, he launched a popular and successful literary career, with twenty of his plays produced on the Paris stage between the 1840s and 1860s.

“The Mulatto” is not set in the continental United States, but its location, Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) in the West Indies, is an important site of slavery and revolution in the African diaspora where plantation slaves experienced barbarous conditions eliciting comparison to Louisiana sugar plantations.[2] Designating Louisiana as an “appendage of the French and Spanish West Indies,” Thomas Marc Fiehrer perceives significant links between the two, including “shar[ing] the socio-economic expreience of the larger circum-Caribbean culture, (3–4), and Louisiana’s becoming a major sugar producer as Saint-Domingue had formerly been. Louisiana, like Cuba, also experienced the “same cycle of expansion and intensification of slavery after 1800 which had occurred in Saint-Domingue between 1750 and 1794,” and many planters, refugees, and free persons of color (many of who had migrated to Cuba first) found Louisiana a “politically desirable point of relocation . . . , afford[ing] . . . an ecosystem comparable to that of the [Caribbean] islands” (4). With the expansion of sugar-plantation slavery came familiar atrocities (10).

Although little known in its era, “The Mulatto” presents the binary of submission and rebellion that became a motif in US based slave narratives and novelized autobiographies treating racialized sexual harassment and/or exploitation of mulattas such as Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of Slave Girl, antislavery novels such as William Wells Brown’s Clotel or; The President’s Daughter and Hannah Crafts’s The Bondwoman’s Narrative, and even late nineteenth-century southern local color stories with embedded former slave storytellers, such as Charles Waddell Chesnutt’s Uncle Julius. In exposing the brutality of the slave system, such as the impact of miscegenation on persons of mixed race; the sexual violation of enslaved persons; and the physical and psychological brutalities of slavery — particularly the devastating effects on family life of whites as well as on blacks — “The Mulatto” deploys strategies for antislavery protest writing that will appear in antebellum slave narratives and anti-slavery novels and in postbellum fiction about slavery.

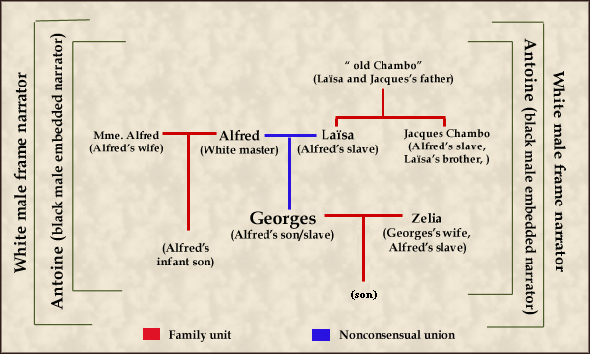

Liberated Narrative Voice

“The Mulatto” features a frame narrator, a white man who functions as a sympathetic and tolerant sounding board to whom Antoine, an old man still presumably a slave and the story’s embedded narrator, freely recounts a harrowing narrative of his friend Georges, a mulatto slave whose master is also his biological father.[3] It is Georges’s master-father, Alfred, against whom Georges directs retributive justice, killing him for allowing Georges’s wife to be put to death for spurning Alfred’s sexual advances. After poisoning Alfred’s wife, Georges beheads his master with an ax and then takes his own life upon discovering that he has murdered his own father. Séjour’s tragic narrative reveals that the slave, like his master, has succumbed to evil as his depravity stems from the corrupting effects of slavery.

Séjour’s character, Antoine, a proud, imposing, elderly slave raconteur, creates a narrative that exposes the psychological tensions and physical violence brought about by the violation of the humanity of black slaves and which affects slave owners as well as their bondpersons. Antoine comfortably and confidently addresses a nameless white listener, an individual about whom he feels no rigid class or race barriers. Moreover, this man, who serves as the frame narrator, gives us Antoine’s story of Georges apparently as it was told to him, an uncensored, melodramatic tale of the tragedy spawned by slavery, with his primary focus being on the victims of its inhumanities. Antoine’s story of Georges, which evokes sympathy for the innocent black slave characters suffering under white oppression, exemplifies racial melodrama, anticipating the form that Linda Williams examines in Playing the Race Card: Melodramas in Black and White, From Uncle Tom to O. J. Simpson. Williams, who views melodrama as typifying “popular American narrative . . . when it seeks to engage with moral questions,” notes that the “moral legibility” of actions within racial melodramas depends upon the representation of victimized innocents who acquire virtue through suffering, a script intended to evoke the social consciences and emotions of readers (12, 17).

In Antoine’s embedded narrative, the master Alfred is depicted as a vain, hideous and merciless villain and the slaves whom he exploits physically and emotionally—Laïsa, Georges’s mother; Georges, his unacknowledged son; and Zelia, Georges’s wife—all become lost innocents, unnecessary victims of the white man. As Antoine begins to talk, prefacing the story, it becomes clear that he can vent his discontent/ and outrage blatantly and speak honestly to the authorial narrator, even to the extent of adopting a cynically editorializing voice and using ideological discourse. In his encounter with this white man, Antoine’s effectiveness as a functional mouthpiece and as a credible and reliable character is not diminished by such annoyances as dialect and and humiliatingly submissive behavior in his encounter with this white man, especially for today’s readers who are knowledgeable of black portraiture in nineteenth-century American white-authored texts such as John Pendleton Kennedy’s Swallow Barn (1832), William Gilmore Simms’s The Yemassee (1835), and Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus tales. Antoine preserves his dignity, consequently escaping reduction to a stereotype. After shaking hands with the white man, who treats him with dignity, Antoine receives a reaffirmation, an invitation to voice his stark, bitter recollections of the dehumanizing effects of slavery. Antoine’s monologue begins with an undiluted tirade precipitated by his thoughts of the story he is about to tell of the ill-fated Georges and his master-father:

“But you know, do you not, that a negro’s as vile as a dog; society rejects him; men detest him; the laws curse him. . . . Yes, he’s a most unhappy being, who hasn’t even the consolation of always being virtuous. . . . He may be born good, noble, and generous; God may grant him a great and loyal soul; but despite all that, he often goes to his grave with bloodstained hands, and a heart hungering after yet more vengeance. For how many times has seen the dreams of his youth destroyed? How many times has experience taught him that his good deeds count for nothing, and that he should love neither his wife nor his son; for one day the former will be seduced by the master, and his own flesh and blood will be sold and transported away despite his despair. What, then, can you expect him to become? Shall he smash his skull against the paving stones? Shall he kill his torturer? Or do you believe the human heart can find a way to bear such misfortune?”

“You’d have to be mad to believe that,” he continued, heatedly. “If he continues to live it can only be for vengeance; for soon he shall rise. . . and, from the day he shakes off his servility, the master would do better to have a starving tiger raging beside him than to meet that man face to face.” (354)

Antoine’s sobering revelation foreshadows the story of Georges, his mother, his wife, his master Alfred, and his master’s wife, establishing a credible basis for the traumas both of slaves who have experienced the victimization and abuses of bondage, and of white masters depraved by unchecked power.

Restricted Space

Through Antoine, Séjour interjects commentary that accentuates that his narrative’s hortatory intent. In this way, Séjour controls how he wants his dour tale to affect his readers. Georges is the product of a rape. His father is his white master Alfred, and his mother Laïsa is a young Senegalese woman whom Alfred purchases at a slave auction for his personal sexual gratification. Antoine emphasizes Laïsa’s humanity, a humanity often violated or repressed because of her own helplessness in the institution of slavery. As his property, Alfred exploits Laïsa sexually. She retains no control over her body or her life’s course. For example, just after she has been purchased, a tearful and frightened Laïsa unexpectedly encounters her brother Jacques Chambo from whom she had been separated and excitedly embraces him. The reunion of brother and sister, both orphans, and the sentiments connected with it are short lived when a cruel overseer lashes Jacques, forcefully separating him from Laïsa. Slaves evinced their humanity when they exhibited genuine emotions before their white oppressors, but white slaveholders who regarded their slaves as commodities, viewed such displays of feeling as subversive—a form of rebellion. These emotional outbursts had to be suppressed in order to force slaves to recognize their white-imposed, non-human status. Dysfunctional family relationships are representative of the place of fathers and mothers in slave societies. Both black slave women and men such as Séjour’s Laïsa and Jacques become constructs of the white slave-holding patriarchy, which, in enslaving them, Hortense J. Spillers notes, “sever[s] . . . the captive body from its motive will, its active desire” (67). In further addressing the effects on the slave’s identity, Spiller points out:

1) the captive body becomes the source of an irresistible, destructive sensuality; 2) at the same time—; in stunning contradiction —the captive body reduces to a thing, becoming being for the captor; 3) in this absence from a subject position, the captured sexualities provide a physical and biological expression of “otherness” ; 4) as a category of “otherness,” the captive body translates into a potential for pornotroping and embodies sheer physical powerlessness that slides into a more general “powerlessness,” resonating through various centers of human and social meaning. (67)

This lack of human acknowledgement is also seen in Georges, Laïsa’s son, a mulatto who does not know who his father is and who consequently feels a sense of emptiness. While Georges likes his master “as much as one can like a man,” and his master “esteem[s] him, but with that esteem that the horseman bears for the most handsome and vigorous of his chargers” (357), their dynamic is a consequence of the black-white binary dictated by the systemic structure of slavery. As a result, Georges experiences intense remorse, the result of being denied the identity of his own father, an identity his dying mother Laïsa refuses to disclose to him. After Laïsa’s death, Georges, like his mother and her brother Jacques, is, in a figurative sense, an orphan.

Although Georges is seriously wounded saving his master’s life from would-be murderers, Alfred tries to seduce Georges’s wife, Zelia, during his convalescence. She resists Alfred’s overtures, refusing to compromise her virtue for her master. As Antoine explains, Alfred, “instead of being moved by this display of a virtue that is so rare among women, above all among those who, like Zelia, are slaves, and who, every day, see their shameless companions prostitute themselves to the colonists, thereby only feeding more licentiousness” (359), allows his lustful desires to govern his actions. Zelia repeatedly resists him—a testament of the strength of Zelia’s humanity and of her love for her husband— and causes Alfred, in his last desperate effort to seduce her, to lose his balance, striking his head as he falls. Tragically for Zelia, colonial laws dictated that the slave must be blamed and executed for her master’s injury.[4]

Zelia’s action, deemed rebellious within the dictates of the system of slavery, proves for the slave doubly devastating, resulting in her death as well as the destruction of her family. Georges pleads persistently and passionately to Alfred to spare his wife. When that fails, Georges angrily condemns his master as a “scoundrel,” even threatening his life if Zelia is executed. Alfred, however, remains adamant. He shows no mercy. Alfred’s recalcitrance precipitates his own murder and the murder of his wife at the hand of the vengeful Georges three years later. Only in the interval, after securing his two-year-old son and running away from his master, to a free space, “those thick forests that seem to hold the new world in their arms” and living among the Maroons, slaves, who, like Georges, “have fled the tyranny of their masters” (361), does Georges savor a semblance of what freedom means.

In Séjour’s bleak story, there are no winners, for Georges also kills himself, since he apparently cannot live with the guilt and remorse. In avenging Zelia’s death, Georges has also killed his own father, completing the destruction of his family. The story’s concluding scene is strikingly symbolic. Georges severs his father’s head with an ax just as Alfred tries to tell him that he is his father (364). The word “father” is severed, broken in two, a reminder that in a slave society normal paternal connections could not exist with slave children. Georges’s action results in two children, one mulatto (his son) and the other white (Alfred and his wife’s son), being orphaned. For both the slave boy and the free white boy of “The Mulatto,” family is destroyed. Yet Alfred’s child, by token of his race and class, will likely reap the benefits from his dissolved family. As Hortense Spillers comments, “the vertical transfer of bloodline, of a patronymic, of titles and entitlements, of real estate and the prerogatives of ‘cold cash,’ from fathers to sons and in the supposedly free exchange of affectional ties between a male and female of his choice—becomes the mythically revered privilege of a free and freed community” (74), of which the white child is beneficiary. Yet for the slave this takes on a different, constricted meaning: Georges and Zelia’s orphan son will, as long as he remains in bondage, enjoy no privileges. Séjour conflates magistricide and patricide, so that in killing his master and father, Georges has killed part of himself. In terms of the rebellion-submission binary, Georges’s act of ultimate rebellion is equated to his ultimate self-submission as an enslaved man. In other words, Georges’s submission is the result of the oppressive and destructive effect of his enslavement on his mind and his spirit. For Georges, submission and rebellion as possibilities for manhood are inextricably linked, if irreconcilable.

While this situation, perpetuated by the systemic structure of slavery, is dismal for Georges, there exists a third alternative in Antoine, the narrator. Having lived for seventy-plus years, Antoine has succumbed to neither magistricide nor suicide as a response to slavery; instead, he tells stories about slavery. These stories provide an outlet for voicing commentary as a counterpoint to the tragic outcome of Georges’s master-slave story. The narrator’s stories also alert his white listener, and Séjour’s readers, to the destructive consequences of slavery.

Clotel’s Rebellion

The submission-rebellion binary that Séjour employed in “The Mulatto” illuminates one consequence of the racial double standard as exercised in the sexual violation of enslaved persons and its corrosive effect on family life. This binary also appears, with some modifications, in subsequent African-American slave narratives and anti-slavery novels of the antebellum period. Examples abound in literature of mixed-race women as victims of racialized sexual exploitation, typically stemming from the systemic structure of slavery. One example is found in William Wells Brown‘s novel Clotel; or, the President’s Daughter (1853).

In Clotel, the authorial narrator bitterly protests the separation of members of a slave family. Clotel, who is a quadroon and can pass for white, is separated from her family, her mother Currer and her sister Althesa, and is sold at auction to a white man desiring her for his mistress. The notion of family unity and cohesiveness is violated as each of these three female slaves is sent to different places under different sets of circumstances. As in Laïsa’s case, the auctioneer promotes Clotel as a highly desirable object, emphasizing her beauty, purity, and nobility of character as her principal selling points, traits making her marketable as a sexual commodity.

As a slave, Clotel, like Laïsa and Georges’s wife, Zelia, has no rights, no choice regarding how she is treated, where she will live, or what will happen to her. Although her white master Horatio Green seems fond of Clotel, making her his mistress, and moving her to an apparently idyllic space in Virginia, and although the couple has a daughter during their relationship, Green, who marries a wealthy white woman from a prominent family, succumbs to his wife’s jealousy and his father-in-law’s demands that he sell Clotel. In placing his social and political aspirations above the love he may feel for Clotel, Green acts expediently, allowing his father-in-law to sell his slave mistress. Her sale forces her from her former refuge and separates her from her beloved daughter. Clotel’s tenuous security continues to be threatened, as she is sold two additional times. Her second new master attempts to seduce her with “glittering presents” and the likelihood of ensuing rape should she resist. Like Zelia in “The Mulatto,” Clotel rebels against the space in which her humanity remains in jeopardy. Facing sexual exploitation, Clotel flees. In Chapter XIX, Clotel’s rebellion becomes a successful, albeit momentary, escape in which, although ably impersonating a white invalid gentleman, she gives in to her maternal instincts. She forgoes her autonomy by returning to Virginia, intending to reunite with her daughter. Clotel has returned to a space where she is regarded as property, without control over how she will be used. While Clotel’s escape—her rebellion against her master— has been skillfully executed, she feels that she cannot live a life of freedom in a place removed from her dear daughter. Her rebellion, if she continued to pursue her freedom, then, would become the equivalent of her family’s destruction.

Zelia succumbs to the systemic structure of slavery that makes rebellion against the master the equivalent of self-immolation. In contrast, Clotel temporarily escapes this fate by rejecting her freedom and returning to Virginia in hopes of a mother and child reunion. Clotel risks re-enslavement, a return to oppressive conditions in place where, if recaptured, she will be forced back into bondage. Yet Clotel’s actions do not bring about reunion. Recaptured and incarcerated in the District of Columbia — the seat of national government symbolizing the liberties that slaves are denied — Clotel confronts her imminent sale in the New Orleans market. There, she will likely be sexually exploited and never see her daughter again. Her rebellion suppressed, Clotel escapes once more, but when faced with recapture, chooses to jump to her death off a Potomac bridge.

Local Color

Another variation in fictional depictions of the effects of oppression on slaves emerged during the postbellum period, the heyday of the local color story. Often, local color set in the Mid and Deep South employed a frame and an embedded narrative, the latter recounted by an elderly African-American male and former slave. In this raconteur, we find a more restrictive binary pattern than Séjour used in “The Mulatto.” Local color stories generally follow two patterns. Derived from stories slaves told, they can be allegorical beast fables, treating power struggles and survival under an oppressive system comparable to slavery. These stories are predicated on an inequitable double standard, with the power structure under the control of predacious animals. Examples are the Uncle Remus stories of Joel Chandler Harris. A second type presents a more direct rendering of slavery’s brutalities and exploitation, such as Charles Chesnutt‘s conjure stories as told by the loquacious Uncle Julius.

Chesnutt’s “The Goophered Grapevine” (1887) features a multi-dimensional and affable storyteller in Uncle Julius, who still resides in the same place where he had been a slave. Uncle Julius speaks in quaint and comical dialect, creating an impression quite different from Séjour’s straightforward, serious, and outspoken Antoine. In the conciliatory, non-controversial conventions of local color, Chesnutt portrays Uncle Julius as polyvocal, assuming competing poses and agendas. Julius is an entertainingly imaginative raconteur whose story involves the supernatural, folkloric, amusing, and outlandish descriptions. He is a cunning con artist and economic opportunist, a simple primitive, and a subdued social critic—contradictory postures reflecting amiability and rebelliousness. Like Séjour’s Antoine, Julius, in telling his story of imagined spaces, works within the binaries of rebellion and submission, white and black, domination and abjection. Through him, Chesnutt dilutes and mellows the underlying serious social implications of Julius’s embedded tale, establishing a comfort zone distancing the story’s enslaved characters from implied readers. While Julius’s story of Henry, the victimized slave, does focus on a dehumanizing aspect of slavery (Henry is economically exploited by his greedy master who commodifies him in his restricted space as a slave), the manner in which Julius tells the story is divertingly entertaining. Julius’s narrative focuses principally on Henry’s predicament rather than on the slave’s interior self. It neither engages the sensibility nor arouses the moral consciousness of the frame narrator, a man from Ohio seeking to purchase the former plantation to whom Julius relates his story, or that of the implied reader.

Chesnutt used the rebellion-submission binary in several other conjure tales. In “Po’ Sandy,” Julius’s story gains him temporary use of the old schoolhouse, a space for religious services. In “The Conjurer’s Revenge,” Julius gains power within his present space, shrewdly employing a tale to circumvent his white employer’s buying a mule, and to set up a scam where he purchases a defective horse instead. In “Mars Jeems’s Nightmare,” Julius again makes a small gain, winning his white female listener’s sympathy so that she gives his unreliable grandson a second chance to continue to work for her family. The outcomes of these tales exemplify Chesnutt’s manipulation of frame plots, creating opportunities within imagined spaces. Julius, although gaining some material advantage, remains oppressed. Moreover, the subtexts of his embedded narratives prove ineffectual in inciting understanding and empathy.

Conclusion

With its early publication date and its tragic portrait of slavery’s atrocities and effects in the plantation space of the French West Indies, Victor Séjour’s “The Mulatto,” is an important literary text. Séjour depicts African bondage in Saint-Domingue, a subject that would become a major concern in nineteenth- and twentieth-century writing. At nineteen, Séjour’s parents sent him to Paris to further his education, pursue broader opportunities, and cultivate his talents. Assimilated into French society and the Parisian literary culture and living without the race-based constraints of his native New Orleans, Séjour passed the rest of his life in France, distinguishing himself as a dramatist. In “The Mulatto,” his only short story, Séjour tapped into the subject of African bondage, possibly inspired by his father, Juan Francois Louis Séjour Marcou’s Haitian experience and that of other free men of color and former slaves from the French West Indies.

In “The Mulatto,” Séjour wrote of submission and rebellion in Saint-Domingue. He wrote in the language of his newly-adopted country, employed an embedded black slave narrator to recount the grim story-within-the-story, and published his fictional account in a Parisian anti-slavery journal sponsored by free men of color like himself.

“The Mulatto” anticipated renditions of grisly and melodramatic scripts featured in abolitionist narratives (autobiographical, fictional, or some combination of the two), but Séjour’s story was all but unknown in the US before Philip Barnard’s English translation appeared in 1995 in the Norton Anthology of American Literature. The new publication of “The Mulatto” places it amid African Diasporic, post-colonial, US southern, and New World Studies. These fields of scholarship have encouraged the discovery and reappraisal of writers with origins in various locales, but who, like Séjour, adopted new nationalities and loyalties even as they were forgotten in their native countries. This analysis of “The Mulatto” suggests the connections among African bondage texts that cross cultures and societies, texts that expose the effects of slavery, of submission and rebellion, as they narrate this history.

Appendix

Notes

- Yellin, who treats this icon of the kneeling supplicant slave in chains in chapter 1 of her Women & Sisters: The Antislavery Feminists in American Culture and who notes that such figures helped to serve the purposes of the abolitionist movement (5).

- Smith and Cohn reaffirm this claim, positing that the “New World, US, and southern cultures cannot be accurately delineated without reference to the similar influences of African American cultures across the borders of the southern United States” (4).

- Though the precise time period of Séjour’s story is not clearly designated and while the setting is Saint-Domingue (Haiti), it is impossible to determine with certainty, even from the context, if Antoine, the embedded narrator in “The Mulatto,” is still enslaved. According to Dayan in 1791 about three-fourths of the 50,000 people in Cap Français were slaves and that throughout Saint-Domingue the population was overwhelmingly slaves (146).

- Commenting on the Black Code and the kinds of punishment inflicted on slaves for acts against free persons in Saint-Domingue, Dayan notes: “Death for the slave who strikes his master, mistress, or the husband or his mistress. . . . Assault and battery against free persons are severely punished even by death if the person struck falls to the ground” (210).

Further Reading

- Bonner, Thomas. “Victor Séjour (Juan Victor Séjour Marcou et Ferrand).” In Afro-American Writers Before the Harlem Renaissance, edited by Trudier Harris and Thadious M. Davis, 237–241. Detroit: Gale, 1986. (Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 50)

- Brickhouse, Anna. Transamerican Literary Relations and the Nineteenth-Century Public Sphere. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Brown, William Wells. Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter. New York: Penguin, 2003. (Originally published in 1853.)

- Chesnutt, Charles W. “The Goophered Grapevine.” Charles W. Chesnutt: Selected Writing. Ed. SallyAnn H. Ferguson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001: 118–28.

- Daut, Marlene. “‘Sons of White Fathers’: Mulatto Vengeance and the Haitian Revolution in Victor Sejour’s ‘The Mulatto.'” Nineteenth-Century Literature 65, no. 1 (2010): 1–37.

- Dayan, Joan. Haiti, History and the Gods. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

- Dessens, Nathalie. From Saint-Domingue to New Orleans: Migration and Influences. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2007.

- Fiehrer, Thomas Marc. “The African Presence in Colonial Louisiana: An Essay on the Continuity of Caribbean Culture.” In Louisiana’s Black Heritage, edited by Robert R. MacDonald, John R. Kemp, and Edward F. Haas. New Orleans: Louisiana State Museum, 1979: 3–31.

- Geggus, David Patrick. The Impact of the Haitian Revolution in the Atlantic World. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2001.

- Handley, George B. “A New World of Oblivion.” In Look Away! The U. S. South in New World Studies, edited by Jon Smith and Deborah Cohn. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004: 25–51.

- Lowe, John Wharton. Calypso Magnolia: The Crosscurrents of Caribbean and Southern Literature. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

- O’Neill, Charles E. Séjour: Parisian Playwright from Louisiana. Lafayette, LA: Center for Louisiana Studies, 1995.

- Piacentino, Edward J. “Slavery through the White-Tinted Lens of an Embedded Black Narrator: Sejour’s ‘The Mulatto’ and Chesnutt’s ‘Dave’s Neckliss’ as Intertexts.” Southern Literary Journal 44, no. 1 (2011): 121–143.

- Séjour, Victor. “The Mulatto.” Translated by Philip Barnard. In The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, 2nd Edition, edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Nellie Y. McKay. New York: Norton, 2004: 353–65. (Originally published as: “Le Mulâtre.” La Revue des Colonies 3 (1837): 376–392.)

- Smith, Jon and Deborah Cohn. “Introduction: Uncanny Hybridities.” In Look Away! The U.S. South in New World Studies, edited by John Smith and Deborah Cohn. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

- Spillers, Hortense J. “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” Diacritics 17 no. 2 (1987): 64–81.

- Williams, Linda. Playing the Race Card: Melodramas in Black and White, From Uncle Tom to O. J. Simpson. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Yellin, Jean Fagan. Women & Sisters: The Antislavery Feminists in American Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989

Originally published by Southern Spaces, 08.28.2007, republished with permission in accordance with the Budapest Open Access Initiative.