Authoritarian regimes feared the disruptive potential of independent thought, perceiving scholars as rivals to political monopoly.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The twentieth century was marked by both astonishing scientific advances and brutal political regimes. Authoritarian governments often feared the disruptive potential of independent inquiry, perceiving scholars not as contributors to national progress but as potential threats to ideological uniformity. From the Soviet Union’s embrace of Lysenkoism, to Nazi Germany’s purges of its universities, to the Chinese Cultural Revolution’s vilification of intellectuals, scholars found themselves at the intersection of politics and truth. Each case demonstrates how authoritarian regimes, insecure in their power, resorted to repression, manipulation, and humiliation to control knowledge itself.

The Soviet Union and Lysenkoism

The Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin provided perhaps the most tragic case of political ideology triumphing over empirical science. Agronomist Trofim Lysenko rejected Mendelian genetics, advancing instead theories of environmentally acquired inheritance that aligned more closely with Marxist principles of human malleability. Lysenko’s appeal to Stalin lay not in scientific validity but in ideological resonance: genetics, he claimed, was “bourgeois pseudoscience,” while his own doctrines promised revolutionary transformations of agriculture.1

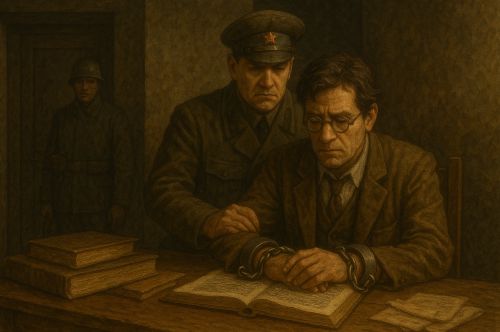

The consequences were catastrophic. Thousands of geneticists were dismissed, imprisoned, or executed for resisting Lysenko’s dogma. Laboratories were closed, curricula rewritten, and entire branches of biology devastated. Nikolai Vavilov, a pioneering geneticist and vocal critic of Lysenko, was arrested in 1940 and died in prison three years later.2 The silencing of dissent did not merely destroy individual careers; it crippled Soviet biology for decades, delaying agricultural innovations and weakening global competitiveness. Here, the authoritarian regime subordinated truth to political orthodoxy, treating dissent as treason against the state.

Nazi Germany and the Purging of Universities

The rise of the Nazi Party in 1933 transformed German universities into engines of ideological conformity. The regime targeted scholars on racial, political, and cultural grounds, purging Jewish academics, socialists, and others deemed “un-German.” Between 1933 and 1934 alone, more than one in five German professors lost their positions.3 The aim was not only to eliminate enemies but to reconstruct knowledge itself around Nazi principles of race and nationalism.

The regime’s attack on intellectual freedom extended beyond personnel. Public book burnings, orchestrated by Nazi student groups, symbolized the violent rejection of intellectual pluralism. Works by Jewish authors, Marxists, pacifists, and others were cast into flames, demonstrating in theatrical form the erasure of intellectual traditions incompatible with the regime’s ideology.4

For those who remained, complicity often became the price of survival. Scholars adapted their work to Nazi frameworks, producing racial “science” that justified exterminationist policies. Those who refused fled into exile, contributing to the “brain drain” that enriched Allied nations while impoverishing German academia. In Nazi Germany, knowledge became propaganda, and universities became instruments of totalitarian power.

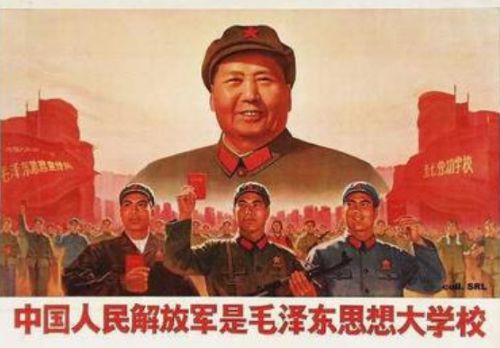

Mao and the Chinese Cultural Revolution

In Maoist China, the decade of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) represented one of the most sweeping assaults on intellectual life in modern history. Mao Zedong, seeking to reassert ideological control, unleashed Red Guards, student militants, the universities. Intellectuals, branded as the “stinking ninth caste,” were accused of elitism and counterrevolutionary tendencies.5

The campaign was not confined to purges. Professors and teachers were subjected to public humiliation, forced to wear dunce caps, confess fabricated sins, and endure beatings. Many were sent to labor camps in rural areas for “re-education,” stripping them of academic status and binding them to physical toil. University classes were suspended, effectively dismantling higher education for a generation.6

The consequences were profound. Intellectual life in China stagnated, with entire cohorts of students losing access to formal education. Science and scholarship were subordinated to political loyalty, and even after Mao’s death, rebuilding academic institutions proved a long and arduous process. The Cultural Revolution revealed the extent to which authoritarian regimes could transform universities from centers of knowledge into battlegrounds for ideological purification.

Comparative Reflections

While the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, and Maoist China differed in ideology (Marxism, fascism, and Maoism) their approaches to intellectual life reveal striking similarities. Each regime sought to control knowledge by silencing dissent, replacing empirical truth with ideological orthodoxy, and transforming universities into instruments of power. The methods varied: in the Soviet Union, scientific theories were reshaped to conform to Marxist dogma; in Nazi Germany, racial ideology dictated both who could teach and what could be taught; in China, the very category of the intellectual was denounced as corrupt and parasitic.

In all three cases, repression carried devastating consequences. Fields of knowledge were set back by decades, entire generations of scholars were lost, and the societies themselves suffered from stunted intellectual growth. The silencing of scholars was not incidental but central to authoritarian power: truth itself had to be domesticated, subordinated to political authority, and purged of independent integrity.

Conclusion

The twentieth century provides sobering evidence of the vulnerability of intellectual life under authoritarian rule. Lysenkoism destroyed Soviet genetics, Nazi Germany’s purges corrupted German universities, and the Chinese Cultural Revolution dismantled an entire academic generation. In each case, authoritarian regimes feared the disruptive potential of independent thought, perceiving scholars as rivals to political monopoly.

To silence a scholar was to silence not only an individual but the very principle of inquiry upon which civilizations depend. The lesson of these tragedies lies not merely in their historical specificity but in their enduring reminder: authoritarian regimes can kill ideas, cripple institutions, and destroy lives, but they cannot fully extinguish the human impulse to seek truth. That impulse, repressed but never erased, reemerged after the collapse of these regimes, proving that intellectual freedom, though fragile, remains irrepressible.

Appendix

Footnotes

- David Joravsky, The Lysenko Affair (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970), 49–53.

- Peter Pringle, The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008), 221–225.

- Alan E. Steinweis, Studying the Jew: Scholarly Antisemitism in Nazi Germany (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006), 12–15.

- Guy Stern, Nazi Book Burning and the American Response (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2003), 201–204.

- Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals, Mao’s Last Revolution (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2006), 118–123.

- Jonathan Unger, Education Under Mao: Class and Competition in Canton Schools, 1960–1980 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 141–146.

Bibliography

- Joravsky, David. The Lysenko Affair. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970.

- MacFarquhar, Roderick, and Michael Schoenhals. Mao’s Last Revolution. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2006.

- Pringle, Peter. The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008.

- Stern, Guy. Nazi Book Burning and the American Response. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2003.

- Steinweis, Alan E. Studying the Jew: Scholarly Antisemitism in Nazi Germany. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Unger, Jonathan. Education Under Mao: Class and Competition in Canton Schools, 1960–1980. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.28.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.