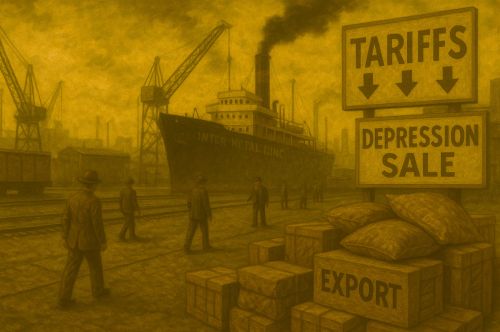

Trade barriers did not initiate collapse, but they hardened it, extending suffering and delaying recovery across continents.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Timing, Causation, and Economic Misattribution

Public memory often compresses complex economic events into single causes, and few episodes illustrate this tendency more clearly than the Great Depression. The Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 is frequently cited as the policy that “caused” the Depression, despite the fact that the American economy had already entered severe contraction months before the legislation became law. The stock market crash of October 1929, followed by rapid declines in industrial production, investment, and credit availability, marked the beginning of the downturn. Any serious historical analysis must therefore begin by separating chronological sequence from causal responsibility.1

This distinction matters because economic crises unfold through multiple phases. An initial shock may trigger contraction, while subsequent policy decisions can either mitigate or magnify the damage. Smoot–Hawley belongs firmly in the latter category. Signed into law in June 1930, the tariff could not have initiated the collapse that began the previous autumn, when output and employment were already falling sharply.2 Treating the tariff as the origin of the Depression obscures the more consequential question of how policy responses transformed a severe recession into a prolonged global catastrophe.

The structure of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act also clarifies its role. The legislation raised import duties on thousands of goods, pushing average tariff rates to their highest levels since the early nineteenth century.3 While intended to shield domestic producers from foreign competition, the policy operated within an international economy still recovering from the dislocations of the First World War. Trade flows, credit systems, and currency arrangements were fragile, and unilateral protectionist action carried risks that extended well beyond national borders.4

Economic misattribution has further consequences for historical interpretation. When Smoot–Hawley is treated as the primary cause of the Depression, it becomes difficult to explain why the downturn persisted for nearly a decade or why recovery required such extensive institutional and monetary change. The more accurate analytical framework recognizes that the tariff intensified existing weaknesses by provoking retaliation, constricting global trade, and undermining international cooperation at a moment when coordinated responses were most needed.5 These effects did not create the crisis, but they reshaped its trajectory.

What follows argues that Smoot–Hawley should be understood as a policy error that deepened and prolonged the Great Depression rather than one that caused it. By examining the timing of the downturn, the political origins of the tariff, and its international consequences, the analysis aims to clarify how trade policy transformed economic contraction into sustained depression. Distinguishing cause from aggravation is not an exercise in absolution, but a necessary step toward understanding how well-intentioned domestic measures can produce disastrous global outcomes.

The Economic Conditions Before Smoot–Hawley

By the late 1920s, the United States economy exhibited significant structural weaknesses that predated any tariff escalation. Industrial output had expanded rapidly earlier in the decade, but gains were unevenly distributed across sectors. Productivity rose faster than wages, limiting broad-based purchasing power and increasing reliance on credit to sustain consumption. This imbalance left the economy vulnerable to contraction once confidence faltered.6

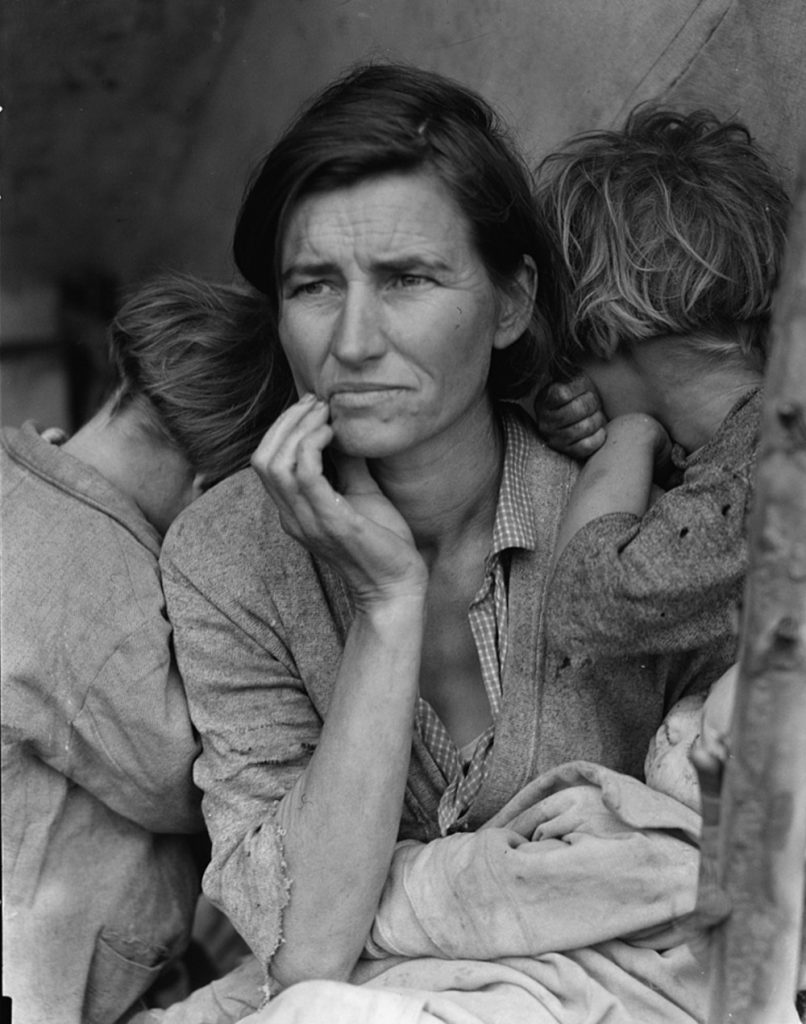

The agricultural sector was already in long-term distress well before the 1929 crash. American farmers faced chronic overproduction, declining prices, and mounting debt throughout the 1920s as wartime demand collapsed and European agriculture recovered. Export markets shrank, domestic prices fell, and rural incomes stagnated.7 These conditions contributed to widespread loan defaults and weakened regional banks, embedding financial fragility into the economy years before national recession began.

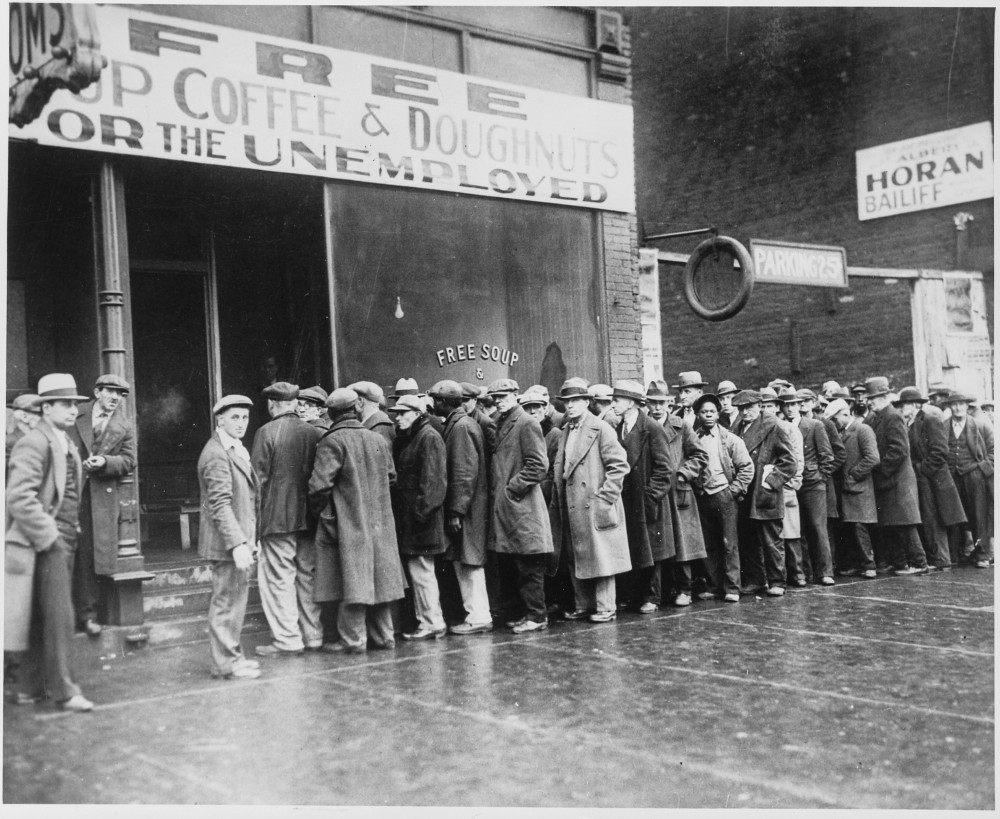

Financial markets amplified these vulnerabilities. Speculative investment expanded dramatically in the late 1920s, fueled by margin buying and easy credit. When equity prices began to fall in October 1929, the collapse quickly spilled into the broader financial system. Bank failures increased, credit availability contracted, and investment declined sharply.8 The resulting contraction in spending accelerated industrial layoffs and reduced consumer demand, reinforcing the downward spiral.

International economic conditions further constrained recovery prospects. The postwar global economy remained distorted by unresolved war debts, reparations, and unstable currency arrangements. European nations depended heavily on American capital flows to service obligations and maintain trade balances. When U.S. lending declined after 1929, these fragile arrangements unraveled, transmitting economic stress across borders even before new trade barriers were enacted.9

By early 1930, the United States was already experiencing a severe recession. Industrial production had fallen substantially, unemployment was rising, and deflationary pressures were intensifying. These developments occurred months before the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act became law, demonstrating that the downturn was well underway prior to any tariff-induced trade disruption.10 The economy entered 1930 weakened by contraction rather than poised for recovery.

Understanding these preexisting conditions is essential for accurate historical analysis. The Depression did not emerge from a single policy decision but from the interaction of structural imbalances, financial collapse, and international fragility. Smoot–Hawley entered an already contracting economy, where its effects would operate not as an initiating force but as an accelerant applied to an unstable system.11

The Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act: Intent and Political Context

The Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act emerged from domestic political pressures that long predated the economic collapse of 1929. Protectionist sentiment had deep roots in American politics, particularly among agricultural interests that had struggled throughout the 1920s. Falling farm prices and declining export demand led many legislators to view higher tariffs as a means of shielding domestic producers from foreign competition. This perspective gained traction well before the stock market crash, framing tariff expansion as a corrective to perceived structural disadvantage rather than a response to economic emergency.12

Congressional dynamics further shaped the legislation’s trajectory. The tariff bill began as a narrow proposal focused on agricultural relief but expanded dramatically as industrial interests sought inclusion. As debate progressed, lawmakers added thousands of tariff increases, transforming the bill into one of the most sweeping protectionist measures in American history.13 This expansion reflected the fragmented nature of congressional policymaking, where coalition-building often produced cumulative escalation rather than coherent strategy.

The executive branch expressed significant reservations about the bill’s scope. Numerous economists, business leaders, and international observers warned that broad tariff increases risked retaliation and trade disruption. Despite these concerns, political momentum proved difficult to restrain. President Herbert Hoover, while publicly ambivalent, ultimately signed the legislation in June 1930, influenced by party pressures and the belief that limited modifications could temper its effects.14 The resulting law reflected compromise and political calculation rather than unified economic vision.

The structure of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act further underscores its political origins. Rather than targeting specific sectors or temporary relief, the legislation raised duties across a wide range of imported goods. Average tariff rates reached levels not seen since the early nineteenth century, signaling a decisive shift toward economic nationalism.15 These increases applied uniformly, without regard to international conditions or reciprocal arrangements, amplifying their disruptive potential within an interconnected global economy.

Understanding the intent and context of Smoot–Hawley is essential for assessing its consequences. The act was not designed as a macroeconomic stabilization tool, nor was it crafted to address financial collapse or unemployment directly. Instead, it represented the culmination of longstanding protectionist impulses operating within a political system ill-suited to anticipate global repercussions.16 Its passage illustrates how domestic policy priorities, when insulated from international realities, can produce outcomes far removed from their original aims.

Why Smoot–Hawley Could Not Have Caused the Depression

The argument that Smoot–Hawley caused the Great Depression collapses under basic chronological scrutiny. The American economy entered sharp contraction in the final quarter of 1929, months before the tariff was enacted. Industrial production fell rapidly following the October stock market crash, while unemployment began rising well before mid-1930. These developments establish that the initial downturn was already in motion prior to any tariff-related trade disruption.17 A policy adopted after the onset of collapse cannot logically serve as its primary cause.

Economic indicators from late 1929 and early 1930 further reinforce this conclusion. Investment spending declined steeply as credit markets tightened and business confidence deteriorated. Bank failures accelerated, reducing money supply and amplifying deflationary pressures. These forces operated largely through domestic financial channels rather than international trade, which still constituted a relatively small share of gross domestic product at the time.18 The mechanisms driving early contraction were therefore financial and monetary, not tariff-induced.

Misattribution often stems from conflating severity with origin. Smoot–Hawley coincided with worsening conditions in 1930 and 1931, leading some observers to assume causation based on proximity rather than evidence. Yet recessionary dynamics were already entrenched by the time the tariff took effect. Production, employment, and prices continued to fall because underlying weaknesses remained unresolved, not because trade barriers suddenly removed a stabilizing force that had previously existed.19 This distinction is essential for avoiding analytical shortcuts.

Recognizing that Smoot–Hawley did not initiate the Depression does not diminish its historical importance. Rather, it clarifies its role within a larger sequence of events. The tariff interacted with an already fragile economy, shaping the depth and duration of the crisis rather than its origin. Proper causal analysis therefore requires separating the sources of collapse from the policies that intensified its consequences, a distinction too often blurred in popular narratives.20

Retaliation and the Collapse of Global Trade

The most immediate international consequence of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act was retaliatory action by America’s major trading partners. Rather than absorbing higher U.S. tariffs passively, foreign governments responded by raising their own barriers against American goods. Canada, the United States’ largest trading partner, acted first, imposing new duties on a wide range of American agricultural and manufactured exports within weeks of the law’s enactment.21 Other nations followed, transforming a unilateral tariff increase into a cascading trade conflict.

European responses reflected both economic necessity and political calculation. Many countries were already struggling with trade deficits, currency instability, and declining reserves under the gold standard. Retaliatory tariffs offered a means of protecting domestic producers while preserving scarce foreign exchange.22 As these measures accumulated, the structure of international trade shifted away from multilateral exchange toward defensive bilateralism, narrowing markets for exporters on all sides.

The contraction of global trade was rapid and severe. International trade volumes declined sharply between 1929 and 1934, with reductions far exceeding the pace of domestic output decline in many countries.23 While falling demand contributed to this collapse, the escalation of tariff barriers magnified the downturn by raising transaction costs and discouraging cross-border exchange even where demand existed. Trade contraction thus reflected policy interaction as much as cyclical weakness.

American exporters experienced immediate losses as foreign markets closed. Agricultural producers were particularly vulnerable, as farm incomes already depressed by overproduction now faced reduced access to overseas buyers. Export-oriented industries in manufacturing similarly encountered shrinking demand, compounding layoffs and investment decline at home.24 These effects were unevenly distributed but collectively significant, reinforcing domestic contraction through external channels.

Retaliation also disrupted financial and shipping networks tied to international commerce. Reduced trade volumes weakened port cities, shipping firms, and trade finance institutions that depended on steady cross-border flows. Declining customs revenues further constrained government budgets abroad, increasing fiscal stress and encouraging additional protectionist measures.25 The feedback loop between trade contraction and fiscal pressure deepened the global downturn.

By transforming tariff policy into an international trade war, Smoot–Hawley helped dismantle the already fragile framework of global economic cooperation. Retaliatory escalation did not merely reduce trade volumes but altered expectations about the reliability of international markets.26 Once confidence in open exchange eroded, recovery became more difficult, as nations prioritized self-protection over coordination. The collapse of trade thus represented not only an economic outcome but a structural rupture in the interwar global economy.

Trade Contraction and Sectoral Damage

The collapse of international trade following tariff escalation affected American economic sectors unevenly, with export-dependent industries bearing the greatest burden. Agriculture was particularly exposed. Farmers who had relied on foreign markets to absorb surplus production found demand sharply reduced as retaliatory tariffs closed off access. This contraction intensified price declines for crops such as wheat, cotton, and corn, worsening rural debt and accelerating farm foreclosures already underway before 1930.27 The tariff shock therefore intersected with long-standing agricultural distress, deepening hardship rather than creating it anew.

Manufacturing sectors tied to foreign demand experienced parallel difficulties. Industries producing machinery, automobiles, and industrial equipment faced shrinking overseas orders at a time when domestic consumption was also falling. Reduced export revenue constrained investment and employment, reinforcing layoffs driven by collapsing domestic demand.28 The loss of foreign markets mattered less for firms serving primarily local consumers, highlighting the differentiated impact of trade contraction across the industrial economy.

Transportation and trade-related services suffered secondary but significant effects. Ports, railroads, and shipping firms depended on steady export and import flows to sustain revenue. As cargo volumes declined, employment in these sectors contracted sharply, particularly in coastal cities and river ports tied to international commerce.29 These losses amplified regional disparities, concentrating economic distress in areas most integrated into global trade networks.

The financial consequences of sectoral damage further prolonged the downturn. Export declines reduced foreign exchange earnings and strained firms reliant on trade finance. Banks exposed to agricultural and export-oriented industries faced rising defaults, adding pressure to an already fragile financial system.30 Trade contraction thus transmitted economic stress across sectors, reinforcing the broader depression through interconnected channels rather than isolated shocks.

Smoot–Hawley and the Prolongation of the Depression

While Smoot–Hawley did not initiate the Great Depression, it played a significant role in obstructing recovery once contraction was underway. By raising barriers to international trade at a moment when domestic demand was collapsing, the tariff limited one of the few remaining channels through which economic activity might have stabilized. Export markets that could have supported industrial output and employment were curtailed just as firms sought alternative sources of demand.31 This restriction did not deepen the initial shock but lengthened the period during which recovery remained elusive.

Trade barriers also interfered with international monetary adjustment. Under the gold standard, countries depended on trade flows to balance payments and stabilize currencies. Retaliatory tariffs reduced exports, drained gold reserves, and intensified deflationary pressures abroad, particularly in Europe.32 As foreign economies contracted further, their capacity to import American goods diminished, creating a feedback loop that reinforced stagnation on both sides of the Atlantic. Recovery became increasingly difficult in the absence of coordinated trade and monetary responses.

The tariff further undermined prospects for international cooperation at a critical juncture. Efforts to stabilize currencies, renegotiate war debts, or coordinate recovery policies required a minimum level of trust among trading partners. Smoot–Hawley signaled a retreat from multilateral engagement, encouraging other nations to prioritize domestic protection over collective solutions.33 This erosion of cooperation delayed policy coordination that might otherwise have shortened the downturn.

By constraining trade, fragmenting markets, and weakening cooperation, Smoot–Hawley extended the duration of economic distress beyond what structural weakness alone would have produced. The tariff did not prevent recovery outright, but it raised the threshold that recovery had to overcome.34 In doing so, it transformed recessionary forces into a prolonged depression, illustrating how policy decisions made under domestic pressure can reshape the trajectory of global economic crises.

International Consequences and Economic Fragmentation

The escalation of protectionism following Smoot–Hawley accelerated the fragmentation of the global economy during the early 1930s. As retaliatory tariffs multiplied, international trade increasingly shifted away from multilateral exchange toward restrictive bilateral arrangements. Nations sought to preserve domestic employment and reserves by prioritizing trade within controlled networks, reducing exposure to unpredictable foreign markets.35 This reorientation weakened the integrative economic structures that had supported global commerce in the interwar period.

Currency instability reinforced these divisions. Countries facing persistent trade deficits and declining reserves under the gold standard were forced to choose between deflationary adjustment and abandonment of fixed exchange rates. As trade barriers limited export recovery, several nations resorted to currency controls or devaluation to regain competitiveness.36 These actions, while stabilizing domestic conditions in some cases, further disrupted international exchange by introducing exchange risk and regulatory barriers alongside tariffs.

The fragmentation of trade and currency regimes had pronounced effects on economically vulnerable regions. Export-oriented economies in Latin America, Eastern Europe, and parts of Asia suffered sharp declines in income as access to major markets contracted.37 Lacking the fiscal capacity to cushion shocks, these regions experienced severe social and political strain. Protectionism among industrial powers thus transmitted instability outward, deepening the global character of the Depression.

International institutions proved ill-equipped to reverse these trends. The League of Nations lacked enforcement mechanisms and depended on voluntary cooperation, which eroded rapidly as national priorities took precedence. Conferences aimed at restoring trade and monetary stability produced limited results, as governments remained reluctant to dismantle protective measures amid domestic pressure.38 Economic nationalism increasingly defined policy choices, narrowing the space for coordinated recovery.

By the mid-1930s, the world economy had fractured into competing blocs rather than a unified trading system. The erosion of multilateral exchange delayed recovery and reshaped global economic relations well beyond the Depression years.39 Smoot–Hawley did not create this fragmentation alone, but it accelerated a process that transformed short-term crisis into long-term structural change, leaving a legacy that would influence economic policy for decades.

Economic Consensus and Historical Assessment

Over time, scholarly analysis of the Great Depression has converged on a broad consensus regarding the role of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act. While interpretations vary in emphasis, most economic historians agree that the tariff did not initiate the Depression but significantly worsened its severity and duration. This assessment rests on comparative analysis of timing, trade flows, and recovery trajectories rather than ideological preference. The weight of evidence places Smoot–Hawley among the most damaging policy responses to the crisis, even as it is distinguished from the underlying causes of collapse.40

One area of agreement concerns the tariff’s international repercussions. Researchers consistently identify retaliatory escalation and trade contraction as central mechanisms through which Smoot–Hawley amplified economic distress. Cross-national studies show that countries more exposed to trade shocks experienced deeper and longer downturns, particularly when protectionist responses were layered onto existing deflationary pressures.41 These findings reinforce the conclusion that trade policy played a critical role in transmitting and intensifying the Depression globally.

Debate persists over the magnitude of Smoot–Hawley’s domestic impact, particularly given the relatively modest share of foreign trade in U.S. gross domestic product at the time. Some scholars argue that this limits the tariff’s explanatory power, while others emphasize indirect effects on expectations, investment behavior, and international coordination.42 These perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Even limited trade disruption can produce outsized consequences when economies are already contracting and confidence is fragile.

The evolution of historical interpretation has also benefited from improved data and methodology. Advances in quantitative analysis, archival research, and international comparison have clarified the sequence and interaction of policy decisions during the early 1930s. As a result, simplistic narratives that elevate Smoot–Hawley to primary cause status have largely receded from serious scholarship, replaced by more nuanced accounts that situate the tariff within a constellation of policy failures.43 This shift reflects greater analytical precision rather than revisionist impulse.

The prevailing scholarly assessment therefore recognizes Smoot–Hawley as a cautionary example of how domestic political pressures can produce policies with far-reaching international consequences. Its legacy lies not in triggering collapse, but in demonstrating how protectionism can exacerbate crisis when economies require openness, coordination, and flexibility.44 The consensus does not absolve other policy errors, but it underscores the tariff’s enduring significance as a case study in economic miscalculation.

Conclusion: Policy Error, Not Prime Mover

The historical record makes clear that the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act cannot be credibly identified as the cause of the Great Depression. The collapse of output, employment, and financial stability began before the legislation was enacted, driven by structural imbalances, monetary contraction, and the breakdown of credit. Yet acknowledging this chronology does not diminish the tariff’s significance. Smoot–Hawley entered an already weakened economy and reshaped the trajectory of the crisis by amplifying contractionary forces at both national and international levels.45 The distinction between cause and consequence is therefore essential to accurate historical interpretation.

What Smoot–Hawley demonstrates most forcefully is the danger of policy responses that prioritize domestic political pressures over systemic economic realities. By triggering retaliatory tariffs and accelerating the collapse of global trade, the legislation undermined mechanisms that might otherwise have facilitated adjustment and recovery. The contraction of international exchange, coupled with the erosion of cooperation, narrowed the pathways through which stabilization could occur.46 In this sense, the tariff transformed a severe recession into a prolonged and globally entrenched depression.

The enduring lesson of Smoot–Hawley lies not in its uniqueness, but in its illustration of how economic crises can be deepened by misaligned policy choices. Trade barriers did not initiate collapse, but they hardened it, extending suffering and delaying recovery across continents. Understanding this episode requires resisting simplistic narratives and instead recognizing how timing, interaction, and institutional fragility shape economic outcomes.47 Smoot–Hawley stands as a reminder that policies adopted in moments of fear can leave legacies far beyond their original intent.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Christina D. Romer, “The Great Crash and the Onset of the Great Depression,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 105, no. 3 (1990).

- Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963).

- Douglas A. Irwin, Peddling Protectionism: Smoot–Hawley and the Great Depression (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011).

- Barry Eichengreen, Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919–1939 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

- League of Nations, World Economic Survey, 1931–1932 (Geneva: League of Nations, 1932).

- Romer, “The Great Crash and the Onset of the Great Depression.”

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Statistics, 1929 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1930).

- Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States.

- Eichengreen, Golden Fetters.

- National Bureau of Economic Research, “U.S. Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions.”

- Irwin, Peddling Protectionism.

- Irwin, Peddling Protectionism.

- U.S. Congress, Congressional Record, 71st Cong., 2nd sess.

- Eichengreen, Golden Fetters.

- Douglas A. Irwin, “From Smoot–Hawley to Reciprocal Trade Agreements,” in The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century, edited by Michael B. Bordo, Claudia Goldin, and Eugene N. White. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1997).

- Alfred E. Eckes Jr., Opening America’s Market: U.S. Foreign Trade Policy since 1776 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995).

- National Bureau of Economic Research, “U.S. Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions.”

- Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States.

- Romer, “The Great Crash and the Onset of the Great Depression.”

- Irwin, Peddling Protectionism.

- Irwin, Peddling Protectionism.

- Eichengreen, Golden Fetters.

- League of Nations, World Economic Survey, 1932–1933 (Geneva: League of Nations, 1933).

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1935 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935).

- Charles Kindleberger, The World in Depression, 1929–1939 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973).

- Douglas A. Irwin, “The Smoot–Hawley Tariff: A Quantitative Assessment,” Review of Economics and Statistics 80, no. 2 (1998).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Statistics, 1932 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1933).

- Irwin, Peddling Protectionism.

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1934 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1934).

- Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States.

- Irwin, Peddling Protectionism.

- Eichengreen, Golden Fetters.

- Kindleberger, The World in Depression.

- Christina D. Romer, “What Ended the Great Depression?” Journal of Economic History 52, no. 4 (1992).

- Kindleberger, The World in Depression.

- Eichengreen, Golden Fetters.

- League of Nations, World Economic Survey, 1933–1934 (Geneva: League of Nations, 1934).

- Patricia Clavin, The Failure of Economic Diplomacy: Britain, Germany, France and the United States, 1931–1936 (London: Macmillan, 1995).

- Douglas A. Irwin, Free Trade under Fire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002).

- Irwin, Peddling Protectionism.

- Barry Eichengreen and Douglas A. Irwin, “The Slide to Protectionism in the Great Depression,” Journal of Economic History 70, no. 4 (2010).

- Christina D. Romer, “The Nation in Depression,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 7, no. 2 (1993).

- Peter Temin, Lessons from the Great Depression (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989).

- Kindleberger, The World in Depression.

- Romer, “The Great Crash and the Onset of the Great Depression.”

- Eichengreen, Golden Fetters.

- Irwin, Peddling Protectionism.

Bibliography

- Clavin, Patricia. The Failure of Economic Diplomacy: Britain, Germany, France and the United States, 1931–1936. London: Macmillan, 1995.

- Eckes, Alfred E., Jr. Opening America’s Market: U.S. Foreign Trade Policy since 1776. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

- Eichengreen, Barry. Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919–1939. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Eichengreen, Barry, and Douglas A. Irwin. “The Slide to Protectionism in the Great Depression.” Journal of Economic History 70, no. 4 (2010): 871–897.

- Friedman, Milton, and Anna J. Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963.

- Irwin, Douglas A. Free Trade under Fire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- —-. Peddling Protectionism: Smoot–Hawley and the Great Depression. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

- —-. “From Smoot–Hawley to Reciprocal Trade Agreements.” In The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century. Edited by Michael B. Bordo, Claudia Goldin, and Eugene N. White. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1997).

- —-. “The Smoot–Hawley Tariff: A Quantitative Assessment.” Review of Economics and Statistics 80, no. 2 (1998): 326–334.

- Kindleberger, Charles P. The World in Depression, 1929–1939. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973.

- League of Nations. World Economic Survey, 1931–1932. Geneva: League of Nations, 1932.

- —-. World Economic Survey, 1932–1933. Geneva: League of Nations, 1933.

- —-. World Economic Survey, 1933–1934. Geneva: League of Nations, 1934.

- National Bureau of Economic Research. “U.S. Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions.” NBER Historical Data.

- Romer, Christina D. “The Great Crash and the Onset of the Great Depression.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 105, no. 3 (1990): 597–624.

- —-. “The Nation in Depression.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 7, no. 2 (1993): 19–39.

- —-. “What Ended the Great Depression?” Journal of Economic History 52, no. 4 (1992): 757–784.

- Temin, Peter. Lessons from the Great Depression. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989.

- United States Congress. Congressional Record. 71st Congress, 2nd session.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Statistics, 1929. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1930.

- —-. Agricultural Statistics, 1932. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1933.

- United States Department of Commerce. Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1934. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1934.

- —-. Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1935. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.16.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.