The transformation of “snake oil” into a term of ridicule belongs not to the medieval period but to the modern redefinition of medical legitimacy.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Serpents Between Medicine, Myth, and Authority

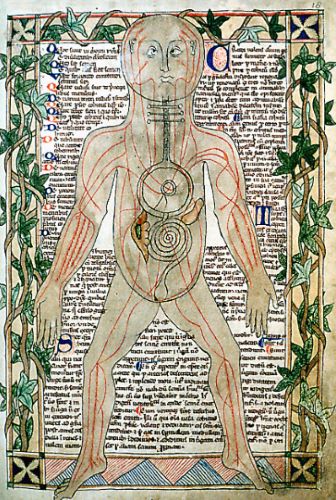

In medieval medical thought, serpents occupied a space that was neither purely symbolic nor merely folkloric. They were feared as agents of corruption and venom yet valued as sources of potent remedies whose efficacy was grounded in inherited medical authority. Snake-based substances such as viper flesh, oils, and compound preparations appeared not at the margins of learned medicine but within its core textual traditions, transmitted through classical writings, commented upon by medieval physicians, and regulated in civic and professional contexts. To modern readers, the coexistence of dread and therapeutic reliance can appear contradictory. Within medieval natural philosophy, however, this duality reflected a coherent understanding of nature as morally neutral, materially active, and medically exploitable when properly understood.1

The intellectual foundations for serpent remedies lay largely in Greco-Roman pharmacology, particularly the works of Galen and Dioscorides, whose writings remained central to medical education throughout the Middle Ages. These authors treated animal substances, including those derived from snakes, as legitimate components of materia medica, capable of producing specific physiological effects when prepared and administered correctly. Medieval physicians did not approach serpents as magical objects but as complex natural bodies whose properties could be analyzed through humoral theory, sensory analogy, and accumulated empirical observation. The persistence of such remedies across centuries owed less to blind tradition than to the extraordinary authority of classical medicine and the absence of a competing explanatory framework that could decisively displace it.2

At the same time, serpents carried a heavy symbolic burden inherited from biblical exegesis, classical mythology, and popular lore. They were associated with deception, poison, and bodily danger, associations that intensified during moments of crisis such as epidemic disease. During plague outbreaks, snakes were sometimes implicated in environmental corruption, yet their bodies were also incorporated into treatments intended to draw out or neutralize illness. This apparent contradiction reveals an important feature of medieval medical reasoning: substances believed to embody danger could, under controlled conditions, be redirected toward healing. The boundary between harm and cure was not fixed but contingent on preparation, dosage, and authoritative knowledge.3

The remedies examined in this essay therefore should not be dismissed as irrational precursors to modern “snake oil” metaphors. They belonged to structured medical systems that distinguished between licensed practice and quackery, between regulated compounds and improvised cures. Preparations such as theriac were produced under civic oversight and debated within learned circles, while simpler snake-based oils circulated through both academic and vernacular channels. By situating serpent remedies within their textual, institutional, and philosophical contexts, this study seeks to recover the internal logic that sustained them and to show how medieval medicine negotiated the boundaries between inherited authority, natural danger, and therapeutic hope.4

Classical Foundations: Galen, Serpents, and Therapeutic Logic

Galen of Pergamon provided the most durable theoretical framework through which serpent-based remedies entered medieval medicine. In his pharmacological treatises, animal substances were treated as legitimate therapeutic agents whose effects could be analyzed according to qualities, degrees, and their interaction with the humors. Vipers, in particular, were understood as naturally potent organisms characterized by heat and dryness, properties that could be redirected toward medical use when properly moderated.5 Because Galen’s works formed the backbone of medical education throughout late antiquity and the Middle Ages, later physicians encountered snake-derived remedies not as marginal folk survivals but as substances already embedded within an authoritative medical system.6

Central to Galen’s therapeutic logic was the insistence that efficacy depended on transformation rather than raw potency. Substances dangerous in their natural state could be rendered beneficial through cooking, dilution, or careful compounding, a principle he applied explicitly to powerful animal products.7 This emphasis shaped later medical practice, encouraging physicians to treat viper flesh and oils as materials requiring technical control rather than avoidance. Risk, within this framework, was not a reason to reject a substance outright but a variable to be managed through preparation, proportion, and timing.8

Galenic medicine also employed analogy grounded in natural observation as a legitimate heuristic tool. Ancient zoological traditions transmitted through Greek medical literature held that adders were deaf, an assumption that influenced the therapeutic use of viper-derived substances for ear disorders.9 While such premises rested on inaccurate natural history, within Galen’s epistemology analogy functioned as a rational guide based on perceived correspondences in nature rather than symbolic magic.10 Treatments derived from this reasoning were presented as plausible interventions within a medical system that acknowledged uncertainty and variation in outcomes.

The controlled role of serpents in therapy becomes especially clear in Galen’s discussions of compound medicines. Snake substances were rarely administered alone but were incorporated into complex antidotes in which multiple ingredients balanced and modified one another.11 In these formulations, viper flesh contributed specific warming or dispersive properties without dominating the preparation, reinforcing the principle that therapeutic value lay in calibrated interaction rather than in any single ingredient.12 This logic would later underpin medieval formulations of theriac, where serpents remained present but carefully subordinated.

Through late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, Galen’s pharmacological writings were translated, preserved, and critically engaged within both Byzantine and Islamic medical traditions.13 Arabic physicians adopted his classifications while expanding pharmacological knowledge and refining preparation techniques, developments that later entered Latin Europe through retranslation.14 As a result, serpent-based remedies circulated within a shared intellectual tradition that prized rational explanation, textual authority, and accumulated experience. Their persistence reflected not blind adherence to tradition but the continuing plausibility of Galen’s therapeutic logic in the absence of a more compelling explanatory alternative.15

Viper Oil and the Medieval Pharmacopoeia

Within medieval pharmacological texts, viper oil occupied a defined and limited role rather than functioning as a universal remedy. Derived from rendered snake flesh and fat, it appeared in learned medical compilations as a topical substance associated primarily with disorders of the skin, joints, and sensory organs.16 Its inclusion reflects the broader medieval reliance on animal-derived substances whose effects were understood through Galenic qualities rather than through symbolic association. Physicians treated viper oil as a warming and softening agent, appropriate for conditions characterized by coldness, hardness, or obstruction, and its use was framed within the same classificatory logic applied to oils derived from plants or other animals.17

Preparation was central to the legitimacy of viper oil as medicine. Medieval medical writers emphasized that improper rendering could preserve dangerous properties associated with venom or decay, while correct preparation neutralized those risks and made the substance therapeutically viable.18 Instructions for producing medicinal oils typically appeared alongside guidance for olive, lily, or rose oils, indicating that snake-derived oils were not isolated curiosities but part of a broader technical repertoire. This attention to process reinforced the distinction between learned pharmacology and unsupervised vernacular use, even though such boundaries were porous in practice.

Medical applications of viper oil frequently intersected with inherited zoological assumptions. The belief that adders were deaf, transmitted through classical authorities, shaped the use of viper oil in treatments for ear pain and impaired hearing.19 These applications rested on analogical reasoning rather than symbolic magic, reflecting a medical culture that sought correspondence between natural properties and bodily conditions. Although such premises were flawed, they operated within a system that valued plausibility and precedent rather than experimental verification in the modern sense.

By the later Middle Ages, viper oil circulated through both academic medicine and household remedy collections, a dual presence that complicates modern distinctions between professional and popular practice.20 Learned physicians continued to reference classical authorities when prescribing it, while practical manuals adapted its use for domestic contexts. This diffusion did not necessarily signal declining rigor but rather the durability of a pharmacological tradition that remained intelligible and useful across social boundaries. Viper oil’s persistence within the medieval pharmacopoeia thus illustrates how snake-based remedies survived not as irrational relics but as carefully delimited tools within an inherited medical framework.21

Snakes and the Black Death: Blame, Fear, and Therapeutic Contradiction

During the fourteenth-century plague outbreaks, serpents entered medical discourse in a markedly intensified and ambivalent way. Plague treatises and natural philosophical writings sought causes that could explain the sudden corruption of air, bodies, and environments, and animals associated with venom and decay were sometimes implicated in these explanations.22 Snakes appeared in discussions of poisonous exhalations, contaminated soils, and noxious vapors, not because physicians believed serpents alone caused the disease, but because they embodied a broader logic of environmental toxicity within humoral medicine.23

At the same time, plague medicine remained fundamentally therapeutic rather than purely accusatory. Physicians operated within a framework that assumed disease resulted from corrupted matter entering or stagnating within the body, especially around lymphatic swellings later termed buboes. Within this logic, substances believed to possess strong drawing or dispersive properties could be applied externally to attract and expel pestilential matter.24 Snake flesh or preparations derived from serpents occasionally appeared in such contexts, applied topically rather than ingested, reflecting a medical logic that sought to redirect danger rather than eliminate it entirely.

This practice exposes a striking contradiction only when viewed through modern assumptions. In medieval medicine, the same qualities that made serpents dangerous also made them potentially useful when carefully controlled. Heat, penetration, and potency were properties capable of both harm and cure depending on context, preparation, and application.25 Physicians did not see this as inconsistency but as a predictable feature of nature, which contained forces that could be moderated and repurposed through medical knowledge. The boundary between poison and medicine was therefore fluid rather than categorical.

Plague treatises themselves reveal significant diversity rather than uniform belief. Some authors warned against excessive reliance on powerful animal substances, emphasizing moderation and the dangers of aggravating an already overheated body.26 Others recommended compound remedies in which snake-derived elements played a subordinate role among botanical and mineral ingredients. This range of opinion demonstrates that serpent remedies were debated rather than universally endorsed, and that medical skepticism existed well within medieval learned culture.

The symbolic weight of serpents nevertheless intensified public fear during epidemic crises, contributing to later retrospective associations between snakes and plague causation. Yet the medical use of snake substances during the Black Death did not arise from superstition or panic alone. It emerged from an established therapeutic logic that sought to confront invisible corruption with materials believed capable of counteracting it.27 Understanding this logic is essential for avoiding anachronistic judgments and for recognizing how medieval physicians navigated uncertainty, fear, and limited explanatory tools while remaining committed to rational medical practice.

Theriac: Serpents as Universal Medicine

Among all medieval snake-based remedies, theriac occupied a uniquely authoritative position. Originating in Hellenistic pharmacology and refined through Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic medical traditions, theriac was conceived as a complex antidote capable of counteracting poisons, resisting epidemic disease, and restoring bodily strength.28 Viper flesh formed a central but carefully regulated component, valued not for symbolic reasons but for its perceived capacity to stimulate internal heat and counteract corruption when balanced with cooling and aromatic substances. The prominence of theriac reflects the medieval conviction that certain remedies derived their power not from singular ingredients but from the orchestration of many forces within nature.

The medical legitimacy of theriac rested heavily on its method of preparation. Classical and medieval authorities insisted on precise ingredient lists, extended aging processes, and skilled oversight, often under civic or courtly supervision.29 These requirements distinguished theriac sharply from improvised snake remedies and reinforced its status as learned medicine. The inclusion of viper flesh was tightly controlled, neutralized through cooking and combination, and justified through Galenic principles rather than anecdotal success. Errors in preparation were believed to render the compound ineffective or even harmful, underscoring the importance of professional expertise.

Theriac’s reputation extended beyond the medical classroom into political and social life. Rulers, nobles, and military leaders sought it as a protective substance, particularly during outbreaks of plague or in regions associated with poisoning risks.30 Figures such as Henry of Grosmont were noted for their reliance on theriac, not as expressions of credulity but as reflections of elite medical consensus at the time. Its widespread use illustrates how serpent-based remedies could operate simultaneously as therapeutic tools and as symbols of access to authoritative medical knowledge.

Despite its reputation as a panacea, theriac was not immune to critique. Medical writers debated its indications, questioned excessive reliance on compound remedies, and cautioned against indiscriminate use, particularly in patients whose humoral balance made strong warming agents inappropriate.31 These debates reveal that theriac’s endurance was sustained by ongoing evaluation rather than blind reverence. The presence of serpents within theriac thus exemplifies the medieval effort to harness dangerous natural substances through regulation, theory, and experience, transforming venom into medicine without denying its inherent risks.

Arabic and Islamic Medical Traditions: Adaptation and Innovation

The transmission of Greco-Roman medicine into the Islamic world between the eighth and tenth centuries provided the conditions for both preservation and innovation in snake-based remedies. Medical writers working in Arabic, such as Ibn Khaldun, inherited Galenic pharmacology through translation movements centered in Abbasid Baghdad, where texts attributed to Galen and Dioscorides were rendered into Arabic and subjected to critical commentary.32 Serpent substances entered Islamic medical literature not as exotic curiosities but as established elements of materia medica, evaluated according to humoral qualities, dosage, and preparation. This continuity ensured that snake-derived remedies remained embedded within a rational therapeutic system rather than drifting into purely symbolic or magical domains.

Islamic physicians expanded upon Galenic classifications by incorporating substances drawn from new ecological and commercial environments. Snake oils and flesh appeared alongside botanical and mineral ingredients unavailable to earlier Mediterranean authors, reflecting the broader geographic scope of Islamic pharmacology.33 Medical encyclopedias such as Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine treated animal substances with analytical caution, situating them within discussions of compound remedies, topical applications, and physiological effects. Serpent-derived materials were thus contextualized within a wider pharmacological landscape that emphasized balance, moderation, and clinical judgment rather than universal efficacy.

In addition to strictly medical uses, Arabic medical and cosmetic literature sometimes recorded snake-based substances in treatments concerned with bodily maintenance, sexual health, and appearance. Oils derived from animals, including serpents, were occasionally combined with plant oils or insects in recipes aimed at stimulating warmth or enhancing the skin.34 These applications did not represent a departure from medical reasoning but rather reflected a continuum between therapeutic and cosmetic concerns common in premodern medicine. The same principles governing disease treatment applied to bodily vigor and external appearance, blurring distinctions that later medical traditions would harden.

The influence of Islamic medicine on Latin Europe ensured that these adaptations did not remain regionally confined. From the twelfth century onward, Arabic medical texts were translated into Latin, reintroducing Galenic medicine enriched by centuries of commentary and practical refinement.35 Snake-based remedies reentered European medical discourse through this channel, often bearing traces of Islamic methodological caution and expanded pharmacological knowledge. Far from preserving ancient medicine unchanged, Islamic physicians acted as critical intermediaries whose engagement with serpent remedies reinforced their legitimacy while constraining their use within carefully articulated therapeutic limits.

Sympathetic Logic without Modern Labels

Medieval physicians did not possess a single, named doctrine equivalent to what later writers would call “sympathetic magic,” yet their medical reasoning consistently employed analogical logic grounded in natural philosophy. Remedies were selected based on perceived correspondences between substances and bodily conditions, an approach inherited from classical medicine and refined through medieval commentary.36 In this framework, serpents were not treated as symbols but as natural bodies whose observable qualities could be aligned with specific therapeutic goals. The logic was pragmatic rather than mystical, operating within a medical culture that sought coherence between nature’s patterns and human physiology.

This analogical reasoning did not imply naïveté or credulity. Medieval medicine accepted uncertainty as an intrinsic feature of healing and therefore relied on plausibility, authority, and accumulated experience rather than controlled experimentation.37 The belief that certain animal traits could illuminate therapeutic uses rested on long-standing assumptions about the intelligibility of nature, not on blind imitation. Snake remedies exemplified this approach: their perceived potency justified cautious use, while their danger demanded restraint and technical mediation. Analogy functioned as a guide, not a guarantee.

Importantly, such reasoning was constrained by professional norms. Physicians distinguished between acceptable analogical inference and illicit practices that relied on incantation, astrology, or occult manipulation.38 Snake-based remedies survived scrutiny precisely because they could be explained within humoral theory and pharmacological classification. When analogical claims could not be reconciled with accepted medical principles, they were more likely to be criticized or excluded. This selective filtering challenges modern assumptions that medieval medicine lacked internal standards of rationality.

Only in the early modern period did these analogical practices begin to be retrospectively grouped under dismissive labels that collapsed diverse medical logics into caricatures. The later metaphor of “snake oil” emerged not from medieval therapeutic practice itself but from shifting epistemological standards that privileged experimental verification over inherited authority.39 Recognizing this distinction allows medieval snake remedies to be understood on their own terms, as products of a coherent, if historically bounded, effort to reason about the body through the natural world rather than as precursors of fraud or superstition.

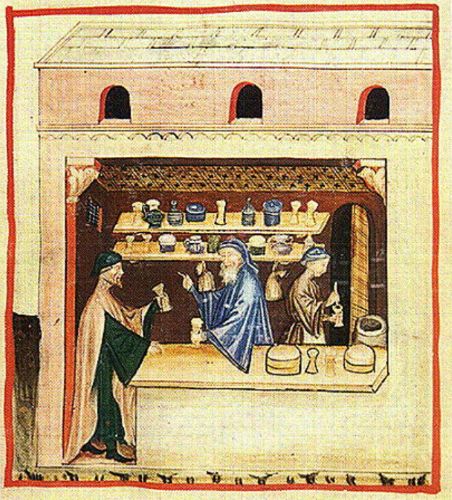

Authority, Regulation, and Skepticism

Snake-based remedies did not circulate in medieval society without oversight or contestation. Learned medicine operated within institutional settings that sought to regulate substances considered powerful or dangerous, particularly those derived from animals. Medical faculties, civic authorities, and court physicians all played roles in defining which remedies were acceptable and under what conditions they could be prepared and dispensed.40 Serpent-based substances were therefore subject to scrutiny not because they were unusual, but because their acknowledged potency demanded professional control.

Regulation was most visible in the production of compound medicines. Remedies that incorporated viper flesh or oils were often restricted to licensed practitioners or approved apothecaries, especially in urban centers where civic authorities monitored drug preparation.41 These controls aimed to prevent adulteration, improper dosage, or substitution, all of which were recognized risks in premodern pharmaceutical practice. The regulation of theriac provides the clearest example, but similar concerns extended to simpler snake-based preparations, which were expected to conform to established pharmacological standards.

At the same time, medieval medical literature reflects sustained skepticism toward excessive reliance on animal-derived substances. Physicians cautioned that remedies involving serpents could aggravate patients whose humoral balance already tended toward heat or dryness.42 Such warnings reveal that medical authority did not equate to unconditional endorsement. Instead, physicians emphasized individualized judgment, adapting treatments to constitution, season, and circumstance. Snake remedies were tools to be used selectively, not universally.

This skepticism also extended to claims made outside learned medicine. Medical writers distinguished between remedies grounded in authoritative texts and those promoted through anecdote, secrecy, or commercial exaggeration.43 Snake-based cures advertised without reference to recognized authorities or proper preparation methods were vulnerable to criticism, particularly as concerns about charlatanism increased in the later Middle Ages. These distinctions complicate modern narratives that portray medieval medicine as uniformly credulous or uncritical.

By situating serpent remedies within frameworks of authority, regulation, and debate, medieval medicine maintained boundaries between legitimate practice and abuse. Snake-based substances persisted not because they escaped scrutiny but because they survived it, repeatedly justified through theory, experience, and institutional control.44 Their history demonstrates that medieval medical culture possessed mechanisms for skepticism and self-regulation, even as it operated within epistemological limits very different from those of modern biomedicine.

Conclusion: From Medieval Remedies to Modern “Snake Oil”

The long history of serpent-based remedies reveals a medical tradition far more structured and self-aware than the modern metaphor of “snake oil” allows. In medieval Europe and the Islamic world, substances derived from snakes were incorporated into therapeutic systems governed by classical authority, humoral theory, and professional oversight. Their use was neither casual nor universally endorsed, but carefully delimited by preparation methods, dosage, and patient constitution. When viewed within this context, snake remedies appear not as aberrations but as rational responses to the medical knowledge and explanatory tools available at the time.45

The apparent contradictions surrounding serpents, feared as sources of venom yet valued as medicine, were not signs of confusion but expressions of a broader natural philosophy that treated danger and efficacy as closely related properties. Medieval physicians understood nature as morally neutral and materially complex, capable of producing substances that could heal or harm depending on how they were handled. Snake-based remedies thus exemplified a wider therapeutic logic in which potency demanded expertise rather than avoidance. This logic persisted because it remained internally coherent even as empirical verification remained limited.46

The transformation of “snake oil” into a term of ridicule belongs not to the medieval period but to the modern redefinition of medical legitimacy. As experimental methods, chemical analysis, and regulatory science reshaped standards of proof, older remedies grounded in authority and analogy lost credibility. The metaphor collapsed centuries of regulated medical practice into a shorthand for fraud, obscuring the historical distinction between learned medicine and commercial deception.47 This shift reflects changing epistemologies rather than the sudden discovery that earlier physicians were irrational or naïve.

Recovering the medieval history of serpent remedies therefore serves a broader historiographical purpose. It challenges narratives that measure past medicine solely by modern outcomes and invites a more nuanced understanding of how knowledge systems operate under constraint. Snake-based remedies endured because they made sense within a world structured by inherited texts, observable qualities, and cautious experimentation. Their story reminds us that medical history is not a linear march from error to truth, but a succession of reasoned attempts to understand the body through the materials nature appeared to provide.48

Appendix

Footnotes

- Vivian Nutton, Ancient Medicine, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2004).

- Nancy G. Siraisi, Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990).

- Monica H. Green, “The Four Black Deaths,” The American Historical Review 125, no. 5 (2020).

- Laurence Totelin, Hippocratic Recipes: Oral and Written Transmission of Pharmacological Knowledge in Fifth- and Fourth-Century Greece (Leiden: Brill, 2009).

- Galen, De simplicium medicamentorum temperamentis ac facultatibus, in Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia, ed. Karl Gottlob Kühn (Leipzig, 1821–1833).

- Siraisi, Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine.

- Galen, De simplicium medicamentorum temperamentis ac facultatibus, Kühn edition.

- Nutton, Ancient Medicine.

- Aristotle, Historia animalium, medieval Latin transmission.

- Totelin, Hippocratic Recipes.

- Galen, De antidotis, in Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia, ed. Karl Gottlob Kühn (Leipzig, 1821–1833).

- Paula De Vos, Compound Remedies: Galenic Pharmacy from the Ancient Mediterranean to New Spain. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press (2020).

- Peter E. Pormann and Emilie Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007).

- Pormann and Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine.

- Nutton, Ancient Medicine

- Siraisi, Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine.

- Nutton, Ancient Medicine.

- Galen, De simplicium medicamentorum temperamentis ac facultatibus, in Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia, ed. Karl Gottlob Kühn (Leipzig, 1821–1833).

- Aristotle, Historia animalium, medieval Latin transmission.

- Monica H. Green, “The Possibilities of Literacy and the Limits of Reading,” in Practical Medicine from Salerno to the Black Death (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

- Siraisi, Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine.

- Green, “The Four Black Deaths.”

- Samuel K. Cohn Jr., Cultures of Plague: Medical Thinking at the End of the Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

- Nutton, Ancient Medicine.

- Siraisi, Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine.

- Luis García-Ballester, Medicine in a Multicultural Society: Christian, Jewish, and Muslim Practitioners in the Spanish Kingdoms, 1220–1610 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001).

- Monica H. Green, Pandemic Disease in the Medieval World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- Galen, De antidotis, in Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia, ed. Karl Gottlob Kühn (Leipzig, 1821–1833).

- Totelin, Hippocratic Recipes.

- Nutton, Ancient Medicine.

- Siraisi, Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine.

- Pormann and Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine.

- Emilie Savage-Smith, “Drug Therapy,” in The Cambridge History of Science, Volume 2: Medieval Science, ed. David C. Lindberg and Michael H. Shank (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- Leigh Chipman, The World of Pharmacy and Pharmacists in Mamluk Cairo (Leiden: Brill, 2010).

- Nancy G. Siraisi, Avicenna in Renaissance Italy: The Canon and Medical Teaching in Italian Universities after 1500 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987).

- Siraisi, Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine.

- Nutton, Ancient Medicine.

- Michael D. Bailey, Magic and Superstition in Europe: A Concise History from Antiquity to the Present (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007).

- James Harvey Young, The Toadstool Millionaires: A Social History of Patent Medicines in America before Federal Regulation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961).

- Siraisi, Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine.

- Chipman, The World of Pharmacy and Pharmacists in Mamluk Cairo.

- Nutton, Ancient Medicine.

- Bailey, Magic and Superstition in Europe.

- Totelin, Hippocratic Recipes.

- Siraisi, Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine.

- Nutton, Ancient Medicine.

- Young, The Toadstool Millionaires.

- Green, Pandemic Disease in the Medieval World.

Bibliography

- Aristotle. Historia animalium. Medieval Latin transmission; modern critical editions consulted where applicable.

- Bailey, Michael D. Magic and Superstition in Europe: A Concise History from Antiquity to the Present. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007.

- Chipman, Leigh. The World of Pharmacy and Pharmacists in Mamluk Cairo. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

- Cohn, Samuel K., Jr. Cultures of Plague: Medical Thinking at the End of the Renaissance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- De Vos, Paula. Compound Remedies: Galenic Pharmacy from the Ancient Mediterranean to New Spain. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press (2020).

- Galen. De antidotis. In Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia, edited by Karl Gottlob Kühn. Leipzig, 1821–1833.

- ———. De simplicium medicamentorum temperamentis ac facultatibus. In Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia, edited by Karl Gottlob Kühn. Leipzig, 1821–1833.

- Green, Monica H. “The Four Black Deaths.” The American Historical Review 125, no. 5 (2020): 1601–1631.

- ———. Pandemic Disease in the Medieval World: Rethinking the Black Death. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- ———, ed. Practical Medicine from Salerno to the Black Death. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Nutton, Vivian. Ancient Medicine. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Pormann, Peter E., and Emilie Savage-Smith. Medieval Islamic Medicine. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007.

- Savage-Smith, Emilie. “Drug Therapy.” In The Cambridge History of Science, Volume 2: Medieval Science, edited by David C. Lindberg and Michael H. Shank, 347–366. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Siraisi, Nancy G. Avicenna in Renaissance Italy: The Canon and Medical Teaching in Italian Universities after 1500. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

- ———. Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

- Totelin, Laurence. Hippocratic Recipes: Oral and Written Transmission of Pharmacological Knowledge in Fifth- and Fourth-Century Greece. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

- Young, James Harvey. The Toadstool Millionaires: A Social History of Patent Medicines in America before Federal Regulation. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.17.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.