It was the attributed symbolic, rather than the physical, characteristics that gave the building its power.

By Dr. William St Clair

Late Senior Research Fellow

Institute of English Studies

School of Advanced Study

University of London

Introduction

Since, in encounters between the present and the past, the present always wins, how might we in the present recover the strangeness of a society that flourished two-and-a-half millennia ago? Can we find ways of throwing off our mind-forged manacles, and instead make an attempt, without preconceptions or agendas, to re-enfranchise those who commissioned, designed, received and used the Parthenon in the classical era by removing the weight of modern practices and traditions? In the chapters that follow, I explore such apparently simple questions as: Why was the classical Parthenon built? What was its purpose or purposes? Why did it take the form that it did? Why, as the eighteenth-century travellers noticed, was it over-engineered?1 Can we do more to release ourselves from traditions, whether admiring and co-opting (‘the highest point of civilization ever reached by humanity’; ‘men-like-ourselves’; ‘our debt to Greece and Rome’) or indignant (‘not all dead white men’)?2 Can we set to one side the influence of modern master narratives, whether they take the form of the arrival of evidence-based Enlightenment ideas or, more recently, of post-colonial theories that present local peoples as being deprived of ‘indigeneous’ ways of interacting with the monuments? Can we clear our minds of the suggestion that the Parthenon is ‘the very symbol of democracy itself’?3

These enquiries grew from the research and writing of a book to which the present volume is a companion: Who Saved the Parthenon? A New History of the Acropolis Before, During and After the Greek Revolution (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2022). That volume considered the meanings conferred on the Parthenon by opinion-formers in modern centuries, beginning at the moment when the bringing to bear of a knowledge of the ancient classical texts began.4 Only in the late seventeenth century, with at most a handful of exceptions, do we see attempts to understand the building within its ancient contexts. We see too that for centuries later, both locally and among foreigners, the older ways of seeing, mainly hostility and indifference, were not displaced, but overlaid, with older traditions remaining active even amongst some of the most highly privileged and well-educated men and women of the nineteenth century.5 We can appreciate more fully the extent to which changes in the meanings attributed to the building were driven by ideas, of which some were recent at the time they were first applied, others very ancient, but all framed within imagined pasts and aspired-to futures. We realise, too, how dependent we are on a number of would-be opinion-formers from elites for recovering even a scanty and patchy understanding of those from non-elite groups who saw the building, with the ever-present risk of assuming that the real reader or viewer can be derived from the implied reader/viewer of the works of opinion-formers. This is the case even for those readers or viewers of modern centuries, let alone those from earlier epochs. The responses of most actual viewers or reader can usually only be found from scattered mentions.6

And although, during the Greek Revolution, as an exceptionally well-constructed and over-engineered building, the Parthenon sheltered those besieged in the Acropolis from artillery bombardment, and some of its marble was turned into cannon balls, it was the attributed symbolic, rather than the physical, characteristics that gave the building its power. During the Revolution, the Parthenon and the other ancient monuments had come to be regarded as ambassadors of a fourth party in the conflict, the famous ancient Greeks of the classical period, and it was that symbolic power which, when converted into the real resources of armaments, military volunteers, money, loans, guarantees, and eventually direct foreign military intervention, ultimately brought success to the Greek Revolutionary cause and enabled an agreement to be made that framed the post-Revolutionary settlement.7

All three of the active participants in the Revolution mobilized the symbolic power of the building, with threats to destroy it by both the Ottomans and the Greeks, as well as negotiations and bargains to save it from further destruction. And the representatives of at least two of the European ‘great powers’ offered, in the event that the building was deliberately destroyed, to harvest selected broken pieces and export them to their own countries in return for immediate direct benefits.8 Indeed, it was at that moment in 1826 and 1827 when both sides, the Greek revolutionaries and the Ottoman high command, were themselves confronting a choice between destroying or not destroying the building, in a trade-off between its military and its contested symbolic power, that what remained of the building was put at the greatest risk it had faced since Elgin’s day.9

And it was the visible presence of the Parthenon and the other monuments of Athens in the landscape at a time when there were few other ancient buildings to be seen in Greece, as well as the many pictures that circulated abroad, that enabled the ancient Hellenes to influence policy-makers and decision-takers during the Revolution. After Independence, they continued to influence the many authors, image makers, street planners and street re-namers, as well as conservationists, restorers, and monument cleansers, who together present the Greek Revolution as a rebirth, regeneration, and resumption of the glories of ancient ‘ancestors’. The moderns had appropriated (‘colonized’) the ancients, but the ancients had also colonized the moderns.

But were those who claimed, during recent centuries, that they had the authority and knowledge, as well as the opportunities, to make the mute stones speak, as aware of the difficulties as our generation has learned to be? With over three hundred years of experience of the new science, including an increasingly reliable understanding of cognition, of speech acts, of visual invitations to perceive the outside world in certain ways, of the techniques of rhetoric, and of many other insights, now available, the chances of being seduced into a simplistic fantasy land, (‘the glory that was Greece’) are themselves better understood.

The risks of imputing modern ideas to the ancients and of judging them against modern criteria (‘presentism’) are, of course, now well understood, and a rapidly growing literature unpicks the characteristics, ‘slippery, amorphous and polyvalent’, as Robin Osborne has warned.10 Indeed, the story of the modern quest to understand classical Athens can be told as a series of warnings against accepting the assumptions and practices of previous epochs. I need not emphasize that there is no good reason why a modern investigator should not turn to modern categories as well as to those used in various pasts, provided he or she consciously and explicitly differentiates between them, and accepts that present day categories are likely in their turn to become an episode that will need to be situated within wider contexts, just as the monument cleansing and romanticism of the nineteenth century, that appeared modern, forward-looking, and normal at the time, can now be seen as interludes.

Studying a Strange World

So how can we, in our own time, attempt to be fair to the ancient Athenians who built the Parthenon? Such an extraordinary and influential episode in the world’s past as classical Athens, I suggest, deserves to have its history told within its own cultural discourses, practices, and norms as well as within others invented later. Although the task of composing such a history is necessarily confined within what is knowable and thinkable in our age, a sincere attempt to prepare such an account is not only a re-enfranchisement of the past from the condescension of the present, but a contribution to an understanding of what used to be called ‘our debt to Greece and Rome’.

The difficulties are numerous and formidable. One difference between ancient Athens and the modern world that is seldom explicitly mentioned in modern writings on the Parthenon, let alone integrated into explanations, is what occurs during the act of cognition itself. Although we can be sure that cognitive processes have remained much the same for most of human existence, they have been overlaid with theories and cultural practices that may reinforce misunderstandings and therefore affect the decisions taken. It follows that, if we wish to understand the aims of those who designed, built, and used the classical Parthenon, we are obliged to take account of the assumptions that were present in the minds of both the producers and the consumers of the building, that is, of the shared civic discourse.

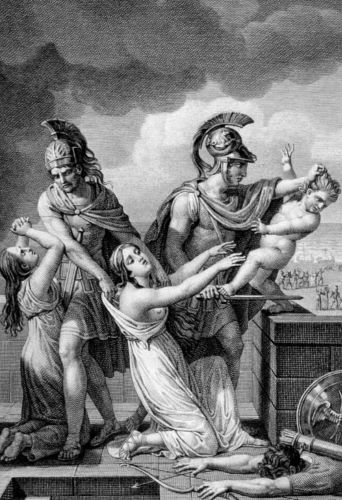

How, for example, can we restore the notions of ‘extramission’ that are seldom mentioned in modern works, but were almost universally accepted, and therefore likely to have been applied, in the ancient?11 The attention paid to the sightlines of vision of characters pictured on vase painting becomes more understandable if we historicize the ancient viewer as imagining a cognitive transaction in which something, often a story of a mythic event with a moral, is transferred into the body and may lodge there, especially if the experience is regularly repeated in a context of high communal excitement, such as at a festival. And underpinning extramission was the then generally accepted theory of four elements, earth, air, fire, and water, that postulated that the beams of light emitted from the eyes derived from a preponderance of heat in the makeup of the body, a component of the cognitive transaction that could be influenced by education, as is explained in, for example, the works of Theophrastus and Hippocrates.12 An alternative theory favoured by Epicurus and repeated in ancient writings over a similarly long period, which postulated that objects emitted atomic particles that caused changes in the viewer’s own atomic make-up, carries many of the same implications.13

And we have examples of how these ancient theories, in whose validity many of the ancients were heavily invested, led to consequences not only for abstract philosophical debate but for the lives of real people. For it was misunderstandings about cognition that led not only to the destruction and mutilation of images, including many of those presented on the Parthenon, but to the targeted oppression of those whom Paul of Tarsus and his emerging imagined community condemned, often with demands for severe punishments, for having accepted and acted upon the invitations to respond to texts and images in ways that were already built into their minds.14

The strangeness of ancient theories of what occurs in cognition cannot be easily grafted on to current understandings, or treated as a matter of aesthetic response. The Greek word for seeing, ‘opsis’, for example, seems normally to have connoted more than the physiological act of looking with the eyes. The authority given to the sense of sight compared with the others made it more like ‘knowing’, a perception that gave rise to an extensive ancient literature on the extent to which things seen, ‘appearances’, could be trusted to be truthful. The primacy given to sight can also help to explain the frequent resort to the rhetorical device of ‘enargeia’, in which a speaker or writer tries to conjure up images in the mind of the listener or reader by presenting events as occurring in real time before their very eyes, when they are actually reports in words of events that occurred in the past.15 Even Isocrates who, during the late classical era, composed model rhetorical speeches that were admired and applied, and who argued that listening to stories, whether, in modern terms, ‘historical’ or ‘mythic’, was a more reliable way of obtaining truthful knowledge about the past than looking at visual presentations, admitted that, in his privileging the sense of hearing, he was departing from a norm.16 Until the discoveries made by Isaac Newton about the nature of light were first given wide currency in early eighteenth-century Europe, all theories of what occurs in cognition were incorrect. How can we find ways of actively distrusting our modern ways of seeing and the modern viewing genres that depend on them?17 Can we historicize the other human senses, touch, smell, and taste, and the role that, in ancient times, they were believed to play in the making of meaning?

Another modern category that, partly as a result, may be more of a hindrance than a help in understanding ancient ways of seeing is the non-ancient notion of ‘art.’ Some champions of the object-centred traditions of western romanticism profess to value the Parthenon and its detached pieces for their ‘aesthetic’ qualities and for their ‘beauty’, often offered as universal and timeless categories rather than as historically contingent imputations.18 To some, operating within the same tradition, it may be enough that ancient objects have survived through to our times so they can be contemplated through modern eyes in new contexts. And some unashamedly accept, if not in these words, that ‘art’, conceptually and institutionally separated from ‘non-art’ as well as from ‘propaganda’, is a colonization, and often also a commodification and commercialization, of the culture of the past and the role that ancient objects, including the Parthenon, played in the customs and performances of that civilization. Such ideas continue to encourage the looting of archaeological sites, feeding the vast illicit international antiquities trade with rich customers far from Greece stoking the demand, and the destruction of knowledge about the societies that produced the objects. Many who support such ideologies might prefer to align themselves with the late Bernard Ashmole, who wrote of ‘that unhappy term “work of art” with all its gruesome implications’.19

Some modern authors have criticised Plato, Aristotle, and indeed all the philosophers of ancient Hellas whose writings survive, even if only in fragments, for not accepting ‘art’ as ‘an autonomous aesthetic domain’.20 According to Jeremy Tanner, the ancients ‘had not developed (or bothered to appropriate from contemporary artists) a vocabulary for visual analysis of comparable richness to that for literary analysis’.21 However, it is not obvious why a modern person seeking to understand classical Athens in its own terms should regard western aesthetics, an academic ‘discipline’ invented in eighteenth-century western Europe, as a relevant conceptual framework for understanding classical Athens.22

In 2019, Daniel O’Quinn used the term ‘pre-disciplinary’ to describe the ways of seeing practised by western visitors to Ottoman lands during the long eighteenth century.23 But this phrase too, besides its implied suggestion that ‘disciplines’ are the preferred way of studying a strange world in which such categories were unknown, excludes many forms of experience, and the categories into which these experiences were organised, that were actually used by classical Athenians. Their practice of including the natural environment, landscape, seascape, skyscape, and non-human living creatures and plants, within their cognitive frame, for example, was far closer to their actual ancient experiences, cognitive practices, and explanations than the modern practice of erecting barriers, both physical and conceptual, round the material art object.24

Plato was not the only classical-era Athenian who regarded what, in modern terms, is called ‘art’, as a deception. Nor was Thucydides unique in regarding poets, by which he meant writers of imaginative literature including dramatists and Homer, as well as composers of pictorial images, as obstacles that stand in the way of recovering truthful knowledge about the past. It was part of the explicitly-stated aim of Thucydides that his written work about the Peloponnesian War would be ‘useful’, a word that, with its cognates and synonyms, he frequently turned to in his aim of helping his own and future generations to distinguish between appearance and truth. And, as it happened, one of the cases where Thucydides foresaw that future generations were at risk of being deceived by visual rhetoric into a false view of the past was when they looked at the buildings of classical Athens, such as the Parthenon, that were still new or under construction in his time, and we can see looking back that events have proved his foresight to be well founded, and that he was destined to be a Cassandra, loved but unheeded.

Recovering Ancient Attitudes to Religion

If the modern notion of ‘art’ risks encouraging a decontextualizing and limiting attitude to ancient objects, the non-ancient category of ‘religion’, that was also absent from classical Greece, carries similar risks. The public discourse of classical Athens included a boast that the city paid more honours to more gods than did any other Hellenic city, a factual claim that contemporaries accepted which is amply confirmed by the literary and archaeological record.25 This ‘omnipresence’ of the gods, this ‘taken-for-grantedness,’ to use Robert Parker’s phrases, was visible in the town, on the Acropolis summit, and in the caves and sanctuaries on the slopes where an almost continuous cycle of ceremonies, private as well as public, were observed and observable.26 There could be no prayers without sacrifices, but also no sacrifices without processions.27

But the word ‘religion’ comes loaded with later associations. To be a ‘priest’ or a ‘priestess’, for example, was to be the holder of an office, some menial, most time-limited, whose duty it was to perform a range of functions relating to the ceremonial practices and the upkeep of the sacred sites, not a permanent status. Nor was there any equivalent of claims to universalism whereby, in the early centuries after the Christian takeover of the eastern Roman empire, ‘priests’ were constituted into imperial ecclesiastical career services that attempted to impose uniformity of practice and of outward displays of belief. As with art, so with religion, the terms are so heavily weighed down with later accretions that it is hard to use them without appending an essay of explanation.28

Some modern authors, impatient with what they perceive as a tendency to impute too much rationality to ancient Hellenic civilization, which they attribute to the ideas of European Enlightenment, have drawn a picture of the men and women of classical Athens cowering in fear of chthonic forces in ‘a spirit-saturated, anxious world, dominated by an egocentric sense of themselves and an overwhelming urgency to keep things right with the gods’.29 And certainly much of what is recorded as occurring in festivals, with charms, amulets, a desperate search for comfort and hope, and a constant looking out for signs of supernatural interventions, resembles modern Lourdes. In ancient authors we are given word portraits of ‘the superstitious man’, not all comic exaggerations. And archaeology has brought to light ‘curse tablets’ that show that the officially recommended gods were not the only ones present in the imagination or in the practice of classical Athenians. We cannot, I suggest, therefore avoid addressing the question whether a belief in ‘the gods’ was embedded in the minds of the people who took part in the ceremonial displays and performances, or whether it would it be more fair to the real men and women of classical Athens, or at least to the mainly socially and economically privileged men and women of whose lives we have most records, to suggest that to many of them ‘the gods’ had become a set of customs, practices, visual presentations, and speech acts that, by repetition and performance, helped to meet other objectives, such as maintaining social cohesiveness within the polity.30 A collection of sayings attributed to Demetrius of Phaleron, who ruled Athens from 317 to 307 BCE, and a prolific author of whose writings little survives, notes as advice on rhetoric: ‘About gods, say there are gods’ and ‘whatever good you do, give the gods the credit for it, not yourself’.31

Furthermore, in classical Athens, as has seldom been noticed, ‘the gods’ are absent from many occasions where we might have expected to find them. They are, for example, scarcely mentioned in the famous funeral oration of Pericles as presented by Thucydides.32 Such references to the gods as occur in funerary orations not only appear perfunctory but are often used as metaphors for the reputation of the dead soldiers. Plutarch, for example, writing much later but quoting from Stesimbrotos of Thasos, a classical-era author, reported of one of Pericles’s other funeral orations: ‘Again, Stesimbrotos says that, in his funeral oration over those who had fallen in the Samian War, he declared that they had become immortal, like the gods, “The gods themselves,” he said, “we cannot see, but from the honours which they receive, and the blessings which they bestow, we conclude that they are immortal.” So it was, he said, with those who had given their lives for their country’.33 The only mention of the gods in the funeral oration of Demosthenes acknowledges their arbitrariness in deciding who should die and who should live. And they are only mentioned in the funeral speech of Hyperides in two brief asides that repeat the advice to continue to honour the old Athenian gods with sacrifices and images. That speech, which follows the standard model, also implies that most of the audience believes that death is non-existence, and that the only ‘immortality’ is in maintaining memory by displaying and performing it.

In funeral orations, the most formal and solemn of public civic occasions, the citizen soldiers are praised for what they did out of their sense of duty to the imagined community of the city and to the continuity of its officially approved past and aspired-to future. ‘Dionysius of Halicarnassus’, the pseudonymous author of a brief advice manual on ‘how to compose funeral speeches’ written some centuries later, besides drawing on the most famous examples and on the Platonic Menexenus, lists other speeches, including some from the classical period now lost. In setting out the strict and long-lasting conventions of the genre, he only mentions the gods in one sentence in which he suggests that the speaker can round off his speech by saying that the dead are better off in the presence of the gods.34 By silently withholding the opportunity to give a share of the credit or the glory to the gods, the words deployed keep the achievement of the dead undiluted.35

And there were other occasions when the gods were either absent or given only a passing mention. In the elegies and epitaphs composed by Simonides and others to commemorate those killed in war, including that for the Spartans at Thermopylae that was frequently relayed in the Second World War, the gods are not mentioned. Indeed, in this genre too, the absence of ‘the gods’ seems to have been a constant feature.36 In Athenian funerary monuments also, whether public such as war memorials or private such as those erected by families, the gods are noticeably absent both from the iconography and from the accompanying words. Although architecturally the ‘little temples’ (‘naiskoi’) of many of the carved memorials follow the conventions of large public sacred buildings such as the Parthenon, we seldom find any mention of the gods. They are not present in the examples selected from databases by Marta González González in a study that attempts to set funerary epigrams in their societal, performative, rhetorical, and not just their modern art-historical contexts.37 Indeed, those mentions we do find can be regarded as exceptions that prove the rule.38 It is as if, by the classical period, some matters, such as death, were too important to be left to the conventions of the official theism of the city. Instead of offering comfort, a traditional function of religion in many cultures, the gods were presented in the stories told about them as arbitrary, unfair, unreliable, selfish, scheming, vindictive, morally worse than humans, and, in some cases, making no attempt to disguise their lack of scruple.39 Nor, in classical Athens, was the absence of the gods a recent phenomenon that some might consider attributing to the influence of the philosophical schools that encouraged their pupils to treat all received and officially authorized ideas with scepticism. Even in the seventh and sixth centuries, of the dozens of inscribed archaic grave monuments erected in Attica, not one in a comprehensive list published in 1961 even mentions the gods.40 A longer list published in 1962 is also almost completely silent about the gods.41 Indeed one of the few exceptions, the inscription on the grave memorial to Phrasikeia, a statue in the round (‘kore’) that has survived in excellent condition seems almost to scold the gods for letting her die unmarried.42 Although at funerals and on such occasions it is likely that processions, prayers, and sacrifices may have been performed, the gods, by being excluded from the permanent record of writing and reading, are given at best a secondary role.

When we put the pieces of evidence together, classical Athens emerges as having many of the characteristics of what is now called a post-religious society, that is, one that attaches a value to adhering to the old forms but for the purposes of conserving identity and promoting social cohesion, not from intellectual conviction. By the time of the Panathenaic oration of Aelius Aristides, the most formal of all expressions of the official self-fashioning of the Athenian polis, delivered in 155 CE, the speaker leads with the theory, in modern terms the narrative (‘logos’) of the city, demoting the gods to second place. And another professional orator, Dio of Prusa, whose professional role and duty was also to uphold the public narratives of cities, felt obliged to tell audiences that they had to really believe in the gods and not just go through the motions.43

In Menander’s comedy, the Tyche, in English ‘Chance’ or ‘Fortune’, the character of Tyche is presented as the only explanation for the unfairness of life. And when Tyche appears as the goddess from the machine who tidies everything up at the end of this and other plays, there is no need to dismiss her as a comic subversion.44 In the world of the tragic drama, which was controlled, financed, and its content patrolled by the institutions of the city, and perhaps also by formal guilds, Tyche could be invoked in the same terms as a god.45 And she was also to be seen on the stories in stone on the Acropolis. In 1839, among the first finds as the Acropolis was cleared after the Ottoman army left was a statue base dateable to c. 360 to 350 BCE that named ‘Tyche’ alongside Zeus.46

Tyche may have been imagined by some as a force that intervenes, a non-Olympian god, a personification of randomness or contingency, a disturbance to a normally ordered universe. But she appears mainly to have been perceived as an alternative to formal theism.47 In a society that, since the time of Homer, had given little weight to ideas of divine providentialism, Tyche offered a way of excusing the moral failings and the indifference of the gods.48 ‘Tyche’ also performs a useful role in exonerating ‘the gods’ and theism generally from having to accept any blame for failing to protect a city, for example when a battle is lost or an earthquake strikes.49 Tyche enabled ‘the gods’ to perform their societal role in classical Athens, without any need for them to exist, or even for them to be generally believed or deemed to exist. This understanding of the frailty and contingence of human experience is markedly different from the theistic providentialism, often presented as benevolent, and other forms of determinism that are built into the self-construction of all the imagined communities mentioned in the book so far, as well as into the self-fashioning of the many ‘great men’, including Stratford Canning and Adolf Hitler, who saw themselves as instruments of destiny. The concept of Tyche is among the components of the public discourse of classical Athens that many in recent times prefer to those still practised in their own societies.50

Myths, Origin Stories and the ‘Emergence from Brutishness’ Narrative

In attempting to recover an understanding of the ancient classical experiences of seeing, sightlines, conventions, and genres, we ought also, I suggest, give weight to what the eighteenth-century philosophers called ‘Nature’, not as a tiresome and unwanted ‘pre-disciplinary’ intrusion to be elided in the same way as eighteenth-century artists and engravers excluded the storks from their pictures of the Parthenon. On the contrary, they and other birds, animals, and insects, ought to be re-inserted. In ancient times, for example, an area of the Acropolis slopes was called ‘the pelasgikon’, a place that, according to a local myth, the Pelasgians, a pre-Hellenic people, had cultivated in pre-historic times.51 The Pelasgians were credited with having been the first to level the Acropolis summit and surround it with a defensive wall before the arrival of the Hellenes, although that story was to come up against another piece of Athenian myth-making, namely that they were autochthonous.52 But the area was also called by a verbal slippage the ‘pelargikon’, ‘the place of the storks’, the birds being a common sight in and around the Acropolis until the Greek Revolution.53 An Athenian inscription of the classical period records an official decree that forbids the setting up of altars in the Pelargikon, so called.54 As a terrace high above ground level where olive trees and other crops could be grown and animals grazed, the Pelargikon/Pelasgikon was part of the Acropolis military defences. It was, as one clever translator has called it, ‘a storkade’.55

During the recent centuries for which we have records, domestic animals, including dogs, goats, donkeys, mules, horses, and chickens were kept on the summit, all of which helped to fertilize and deepen the soil and to encourage the insects on which wild birds fed. In ancient times too, the Acropolis summit was evidently a green space, almost a garden town. In the Ion of Euripides, for example, the rocky slopes of the Acropolis by Pan’s cave where the character of Kreousa claimed to have been raped by Apollo, are contrasted with the ‘green acres’ in front of the temples of Athena on the summit.56 On and around the Acropolis, many species of birds, including storks, owls, pigeons, finches, and sparrows, shared with humans the natural environment for their food and the built environment for their nesting sites. In ancient times, dogs, as agents of both actual and of symbolic pollution, were not normally allowed.57 However, in the numerous festivals, cows, sheep, and domestic fowls were ritually slaughtered, eaten, and their bones burned and thrown away. Grain, fruit, honey-cake, and other food were ritually scattered, and wined poured. So frequent were the rituals, and so inflexible the conventions of no prayers without sacrifice, no sacrifice without a ceremonial procession to the altar where the creature was to be killed, and no eating or drinking without scattering a share for the gods, that the ancient Acropolis, like Delphi and Delos, had developed its own micro-ecosystem of food chains, the hunted and the hunters, the eaten and the eaters, the natural world interacting with the human, the real with the symbolic.58 Fresh water, whether it was drunk, poured, accidentally spilled, excreted, or used in washing rituals, benefited the insects, possibly causing buried eggs of the ‘autochthonous’ cicadas suddenly to hatch.59 The insects benefitted the birds and other creatures that inhabited a local eco-niche higher up the food chain. And we can take it that similar results were encouraged by other scatterings and spillages, whether of dry foods, wine, oil, or the blood and innards of slaughtered animals. All were part of the festival experience.60 Since, in order to be effective, outward conformity is required at least on formal occasions, we should not expect a single answer to the question of how ancient Athenians understood religion. We do, however, have plentiful evidence that the issue was constantly debated in classical Athens, as well as earlier and later, with some writers insisting that, measured against the justifications offered, the whole nexus of temples, shrines, processions, prayers, sacrifices, and feasts was ineffective and, to some, both absurd and dangerous. Indeed, many writers made little secret of the fact that ‘the gods’ were a useful fiction, a ‘nomisma’, something ‘deemed’ to have value, an institution conventionally established and customarily practised because it serves a useful social purpose, without having either to exist or even to be believed to exist.

In the tragic theatre, a public medium that was financed and its content vetted by the institutions of the classical city, gods appear and speak, and characters cast doubt on the existence of the gods. In a fragment of the Bellerophon, a play by Euripides, the character of Bellerophon declares: ‘Does anyone say there are truly gods in heaven? There are not, there are not, unless a fool is willing to make use of the old story’.61 The character of Bellerophon goes on to note the injustice of tyrants who break oaths, sack cities, and get off scot-free, and of small cities that fall victim to the armies of larger cities however much honour they pay to the gods.

The ‘autochthony’ claim, as was discussed in Chapter 16 of Who Saved the Parthenon?, an example of a backward-looking myth of origin or foundation as an event occurring at a specific moment in the past, is an ‘aetiology’ with many parallels in other ancient Greek cities, and still a staple rhetoric of modern nationalisms that thrive on othering. As an element in the discursive environment, it was given prominence in, for example, the west pediment of the Parthenon and other visual objects on the Acropolis, as a characteristic of ‘Athena’.62 We would be anachronistic, however, if we regarded such inventions or elaborations as mere antiquarian lore. They are, I suggest, better understood as a rhetorical reaffirmation of an ‘aristocratic’ ideology that, in classical Athens, had consequences both in dividing Athenians from non-Athenians and in privileging one group of Athenians over others. The autochthony claim, in literal terms nonsensical as Aristotle and others pointed out, was mocked by Antisthenes, a philosopher and contemporary of Plato, one of those who was disenfranchised by the Periclean translation of the myth into political action.63 By promoting difference, whether silently or avowedly, it made claims to superiority, and therefore ultimately the legitimacy and necessity of threats, violence, and war, another omnipresent component of the discursive environment of classical Greece.

Then there is the Athenian conception of time. Besides the climate, the landscape, and the built environment, which the Athenians of the classical period and earlier had turned into a theatre of mythic stories about their past, they had also set their city’s uniqueness within a chronological narrative that began at a remote time and ran to their present day. Together the ‘storyscape’ and the ‘timescape’ as we might call them, provided the coordinates for an explanation, within whose conceptual boundaries the Athenians of the classical era looked backward to a time when their world had first come into existence and forward to successive futures that, to an extent, lay within their own power to shape. This world view sometimes included looking upward to the clear sky, whether during the night or in daytime, where some heavenly objects appeared to be fixed and others to move, which ancient Greek writers had also recorded, turned into stories, and included in their explanations as a skyscape.64 Those phenomena that did not follow obvious patterns, such as strikes of lightning, storms at sea and on land—often damaging and sometimes fatal to human societies and individuals—as well as earthquakes, floods, droughts, plagues, and other disasters that could not be reconciled with notions of benevolent, just, or even interested deities, also attracted a range of stories and explanations, mainly mythical and theistic, that enabled them to be fitted into an overarching, unified, world view. In the opening Preamble to the horrors enacted in Trojan Women, Euripides presents a verbatim conversation between Poseidon and Athena. The two principal deities of Athens come across as selfish, scheming, indifferent to human concerns, vengeful, and petty-minded.65 Not only did Trojan Women obtain the approvals and financing needed to be accepted for production, but it won the prize in 415 BCE.

As for the origin of the universe, it was commonly claimed, not only in Athens but elsewhere in Greece, that there had been a time when only gods existed and they had engaged in a long struggle to bring about some order against the forces of chaos, personified as giants. The ‘gigantomachy’ seems to have become a shorthand for the arrival of a more stable, but always precarious, cosmos, and it was frequently given fixed visual form on Hellenic temples, including the Parthenon, and in the design of fabrics used in ceremonies, such as the peplos (a formal garment worn by both males and females and associated with the mythic age) that featured in the Great Panathenaic, a festival that had been instituted in Athens in the sixth century but that was presented, as with many other institutions, as having existed much earlier.

To explain the earliest stages of human existence, the classical Athenians had access to ancient ‘theogonies’ mainly in the form of lists of names that gave some shape to the past, of which one composed by Hesiod, which has survived, commanded almost as much respect as the epics of the Homeric cycles, of which the Iliad and the Odyssey were accorded primacy over others of which we only have fragments. The classical Athenians knew that these texts had been translated from oral live performance to written, and therefore more fixed, forms in their fairly recent past, and to judge from the numerous quotations, in the classical era it was the fixed forms that were performed at festivals and in competitions. As it happens, the fullest, albeit fictional, account of how classical-era viewers engaged dynamically and collectively with the stories presented in fixed form on ancient temples refers to looking at a gigantomachy.66 The main stages were summarized by the character of Protagoras in Plato’s dialogue of that name, which purports to give the actual words of Protagoras of Abdera, who was born in the early fifth century and was therefore of an earlier generation than Plato. According to this version, no mortal creatures had existed until the gods instructed their servants Prometheus and Epimetheus to make humans, as well as animals and birds, by moulding them from earth and fire, regarded as the primary elements along with water and air.

Of the texts from the classical period that have survived through to our own time, the last and longest of the dialogues of Plato, the Laws, is set in Crete, a location where some of the struggles from which the gods had emerged victorious had allegedly taken place, in and around the terrifying volcanic Mount Ida. The Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus was set on a mountain in Scythia, the remote area north of the Black Sea, where the unrepentant Prometheus is being eternally punished by Zeus, regarded as the ‘father’, that is, the first god to have existed, for stealing from the domain of the gods a knowledge of fire and of how it could be tamed by humans.

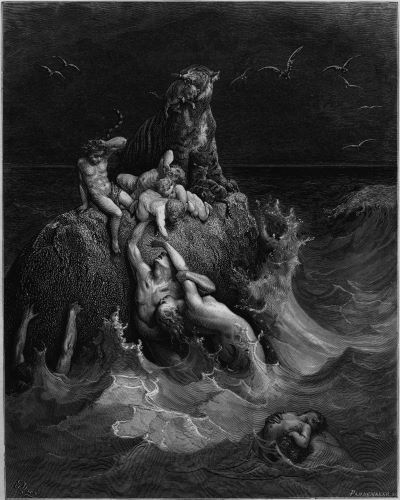

As for the emergence of human beings, a variety of explanations were offered, some of which, such as that of a great flood overwhelming the Aegean basin, may also have been rooted in memories of actual occurrences carried, mainly orally, across generations.67 According to the character of ‘the Athenian’, with whom the other characters in the dialogue seldom disagree, and who may record the views of Socrates or Plato himself, a great flood had overwhelmed the world, from which the only survivors were a few herders of goats and sheep living simple lives on the tops of mountains, who were now cut off from one another. All that they knew of the past before the flood were a few names.68

When time reached the more recent past, the story took on a form that was supported by evidence, partly historiographical and anthropological, but also derived from observation of other living things, animals, birds, and insects, and more rarely of the fish and plants with which humans shared the physical environment. What is common to all is that humans moved from a solitary brutish state, as a first step to living together in extended families in an ‘oikos’, seen as a political as much as an economic institution, before, in some cases such as Athens, coming together as a ‘polis’ that enabled them to do more as a unit than they could do separately, including, in many cases, the building of defensive walls.

The emergence-from-brutishness narrative, though seldom pieced together or integrated into explanations, is to be found both as a description of what occurred in the past and as a framework within which choices about the future should be made, in some of the most formal occasions on which the official ideology of the state of Athens was performed. An account of the brute-to-oikos stage can be found in the brief Homeric Hymn to Hephaistos. To judge from other hymns in the collection, of which the attribution to Homer appears to have been accepted in the classical period, this hymn was probably ceremonially sung at festivals.69 This brute-to-oikos narrative is employed or alluded to at least three times in the formal works of Isocrates.70 As he declared on one occasion, he could add further proofs that ‘no one would think of disbelieving’ based on the creditworthiness of ancient traditions and on actions that were deemed to have occurred.71 The Funeral Oration of Lysias that, unlike the one put into the mouth of Pericles by Thucydides, may have been delivered, declares: ‘For they [our ancestors] deemed that it was the way of wild beasts to be held subject to one another by force, but the duty of men to delimit justice by law, to convince by reason, and to submit to the rule of law and the instruction of reason’.72 The narrative occurs in the tragic drama, put, for example, into the mouth of the character of Theseus in the Suppliants by Euripides, speaking as the spirit of Athens at its best, in a passage that brings together acquired ability to think and to communicate with economic developments in agriculture and trade.73

The narrative is mocked in the comic drama. Aristophanes, for example, in reversing the roles of humans and birds in the Birds, has one bird sneer at another as ‘a most cowardly brute’, the joke being that his fellow bird, in flying away from the bird-catchers who frequented the slopes of the Acropolis and choosing to save himself by quitting the field, was not yet advanced enough to be a citizen-soldier of the polis.74 In the Cyclops by Euripides, a burlesque satyr play, the unheroic character of Odysseus, in an ancient equivalent of the pot calling the kettle black, addresses his noisy, cowardly, and untrustworthy followers as ‘brutes’.75 The narrative is also set out, within a strong teleological assumption about fulfilling the purposes of ‘nature’, in the opening chapters of Aristotle’s Politics.

The brutishness narrative continued to be deployed long after the classical period, and is found for example in the work of first-century-BCE historian Diodorus Siculus.76 His description of the difference between the ‘mused’, who had already developed a civilized life, and the ‘unmused’ who needed more ‘paideia’, repeats features found in the authors of the classical era.77 Later still, more than half a millennium after the building of the Parthenon, it is found in the Forty-Sixth Oration of Aelius Aristides, delivered in 156 CE, in which the earliest humans are presented as living like brutes, from day to day, in holes and clefts in the ground and in trees.78 Thucydides, who was distrustful of the truth value of mythic stories and of imaginative literature, offered a version that related the start of material and social improvement that he observed in Attica, and to a lesser extent in other regions, to the political economy of Hellas as a whole. The situation that he observed in his own time, and which he put into the mouth of Pericles in the Funeral Oration, was one where all the good things of the earth flowed into Athens, and where Athens was also able to gather the fruits of its own soil with as much security as other lands, two apparently separate points that are linked in the speech.79 Thucydides wrote in his summary of the early history of Greece that elsewhere in the Hellenic world, the seas were cleared of pirates by the Corinthians and by the overseas Ionians, making it safe for others as well as for themselves to trade by sea. Thucydides did not need to tell his readership that, apart from live animals, prisoners, and slaves who could be compelled to walk, the landscape of mountains and gulfs made it prohibitively uneconomic to take other goods, including most agricultural products, from one city to another, even with the help of donkeys.80

The ability to trade by sea, Thucydides says, enabled Athens to move from a precarious oikos economy of self-sufficiency, household by household, to one that produced tradable crops for the growing of which the soil and climate of Attica was most suited, including olives and olive oil, which could then be exchanged, with the use of sea transport, for different products grown elsewhere. That move away from an inefficient use of the fixed capital, the land, enabled the Athenian economy to generate ‘surpluses’, a word familiar to modern students of economic development that Thucydides uses twice in his explanation.81 Empirical data from a variety of studies recently collected tend to confirm the account.82 Among the benefits Thucydides mentions are the reduction in the need for every oikos to employ guards, and for men to be normally armed, while the manufacturing and service industries needed to support them could be dispensed with altogether when replaced by social trust. The resulting net reduction in the human resources employed in exploiting the land, whether free or slave, then became available to be redeployed to other productive purposes. From the fragmentary records of Solon, a historic figure, it appears that the transition was managed, with, for example, restrictions on olive oil exports to preserve or slow the reduction of jobs. The change may have been aided by an increasing use of metal coinage, although Athens did not produce its own coinage in Solon’s time, despite having deposits of silver in its territory. Nor is it clear whether Thucydides thought that the move to a polis with walls and political institutions preceded the economic change or was a result. But, in many Hellenic cities, including Athens, these developments ushered in the ‘age of the tyrants’, it being easier for a would-be usurper to extract resources from an economy when they took the form of amphorae of oil, durable and exchangeable as a form of money, than to send his thugs round numerous semi-defended households to seize a goat here, a lump of cheese from somewhere else, and small quantities of grains. So successful was the change that the oil itself was credited by Aristotle, and others, not only with increasing the numbers of men that Athens could field as soldiers or ships of war that could be manned, but with making the men themselves militarily more effective.83

The importance of the olive tree to classical Athens was noted by the character of the Chorus, speaking as the voice of the imagined community, in the Oedipus at Colonos of Sophocles, which, at first sight, is puzzling: ‘It is a tree, self-born, self grown, unaided by men’s hands, a tree of terror to our enemies and their spears, a tree that grows best upon this very land. It is the grey-leaved olive tree, a tree that nurtures our youth, a tree that no youth nor aged citizen can damage or destroy because it is cared for and protected by ever-watching eyes of Zeus Morios and Athena of the grey eyes’.84

As another example, in their puzzling description of olive trees as a ’terror to our enemies and their spears’, the Chorus may be alluding to the increase in useful manpower, such as those who built the ships and manned the fleet, that the shift to tradable crops made possible. And when, writing centuries later but within the same discursive conventions, Aelius Aristides imagines from afar his walks round the Acropolis of Athens, he mentions that ‘when I considered that both trade and naval warfare were gifts of Athena’, he may be confirming the story offered on the west pediment of the Parthenon that connects the naval success of Athens to the economic changes brought about by the cultivation of olives and tradable olive oil.85 The Chorus may also be alluding to the opinion of Aristotle that rubbing the body with oil mixed with water ‘stops fatigue’.86 Aristotle presents his comment as an observation for which he had no explanation, and he may have had in mind the exercising of the body in games that were preparations for war, which became a feature of classical Athens and are alluded to in the funeral oration put into the mouth of Pericles by Thucydides. From our own perspective, we can suggest that neither Aristotle nor his contemporaries appreciated the extent to which consuming olives or olive oil, even in small quantities, can improve the general heath of people whose main diet is grain. Although they were evidently not seen as the nutritious foodstuffs that they are, there are enough references to their being consumed in the classical period for them to have improved the diet, the health, and therefore, the effectiveness in war, of those who consumed them in any amount.87 And it seems likely that, whatever the price that olives and olive oil may have fetched in final markets abroad, in Attica they may have been plentiful, cheap, and perhaps, for many, free for the picking or the gathering.88 As was noted by Duris of Samos, a fourth-century author who knew Demetrius of Phaleron, but of whose works only a fragments have survived, before Demetrius rose to power and indulged himself with grand banquets, he had lived entirely on ‘olives and island cheese’.89

None of the ancient authors whose works we know presented the progress-from-brutishness narrative as inevitable or even as systemically self-generating, as some authors of the European Enlightenment had claimed for their own theories. On the contrary, in the ancient Greek versions, all societies, including those such as Athens who thought of themselves as the most advanced along the trajectory, were always at risk of slipping back. As Plato wrote: ‘Man is a tame animal, as we put it, and if he receives a good education and has the right disposition, he can be the most god-like and gentle living animal, but if his education in the civic values [‘paideia’ in ‘arete’] is inadequate or misguided, he will become the wildest of all animals’.90

Viewing Light and Time

While every generation cannot avoid being influenced by its own time, can we actively hold in check the urge to ask whether the Parthenon ‘resonates’ with our modern experience? And can we put aside the alleged right of individuals to interpret, invent, and impute meanings to the cultural productions of the past as they choose – what the late Wolfgang Iser, the theorist of response to literary works, sardonically called ‘the great adventure of the soul among masterpieces’?91

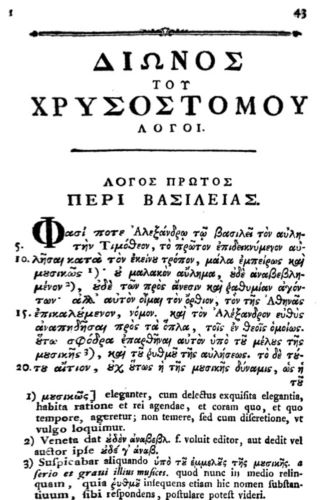

In many respects, our present can rightly claim to be better equipped than the intermediate pasts of the modern centuries for the task of unravelling and trying to understand the intertwined threads that make up ancient cultures. However, there are some respects in which the men and women of classical Athens had at their disposal a range of intellectual means to arrive at a surer understanding of the world in which they found themselves than many modern commentators. One is that, for the classical period and later, almost everyone who was educated at all was educated in rhetoric, meaning the arts of persuasion, which the tradition has tended to associate with the arts of speaking or ‘oratory’ but was evidently also applied to the arts of picturing with visual images. We have a body of excellent, and largely self-consistent, literature that sets out the do’s and the don’t’s, as well as specialist tricks of the trade, including advice on how to make visual images speak as if they were alive. Those who had been trained in rhetoric were, as a result, able to understand, point out, respond to, and if necessary to discount, rhetorical devices when they heard them. Dio of Prusa, who was both a theorist and a practitioner, spent much of the introductions to his public speeches claiming not to be using rhetoric, itself a form of rhetoric, and Dio earned the name ‘Chrysostomos’, the golden-mouthed, or, as a modern person might say, ‘silver-tongued’, which brings out the ambiguity with which the skill was regarded.

Much can be deduced about the classical world from the geographical environment and the sightlines it permitted. Those who commissioned, designed, and caused the Parthenon to be constructed were, for example, evidently concerned with how it appeared from the long and from the middle distances, including from particular viewing stations, some readily identifiable, as I discussed in the companion volume to this book.92 However, apart from the full-frontal view from the west where the entrance was and is situated, the Parthenon could not be seen by those going about their daily business in the town. Nor could it be seen even by those who approached the entrance along the ‘Sacred Way’ along the Areopagus, or by those who approached or left by the peripatos, the road that encircled the Acropolis within the enclosure.

The Parthenon was within the sightlines of those who gathered to take part in the processions that began at a distance from the Acropolis, disappearing below the horizon of their sight as they came nearer. It was still out of sight as they reached the Areopagus, where some processions appear to have halted and where it is possible that at least some of the facilities of the modern frontier zone could be found. But, as now, the Parthenon did not open up to their view until they had passed through the entrance gates of the Acropolis summit, the Propylaia.93

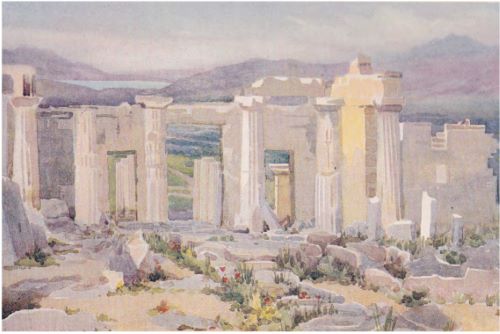

The classical Athenians had lived mostly outdoors in a microclimate with highly unusual characteristics, as they themselves knew, a fact that was noted with surprise and delight as something to be experienced by the visitors from the west from the time of the encounter.94 The light, which had evidently remained remarkably stable over the ancient centuries, was different, not only day by day, week by week, or season by season, but in the course of every day. This ever-changing light, an intrinsic feature of the exceptionalism and the geodeterminism claimed by classical Athens, could still be experienced in the long eighteenth century and for many years afterwards.95 However, for two centuries after the encounter with the classically educated westerners and their books, most images of Athens that were taken abroad were in monochrome, black ink on white paper, a translation of a moving phenomenon onto a fixed flat surface of the lines and dots carved into a metal plate. Even in ancient times, with the exception of designs on fabric, and a few ceramics specially prepared, the Athens that was presented outside Athens was also mainly a duochrome world, known elsewhere, if at all, from the painted images in red and black ceramic that were mostly allusive and allegorical, as befitted the uses they were designed for, such as grave goods containing the ashes of the dead, or as prizes in formal contests such as games and dramatic competitions.

The pre-industrial microclimate of Athens, and the extraordinarily long sightlines it makes possible, can still occasionally be experienced. However after air pollution caused by carbon emissions became a regional, indeed a global, phenomenon, it was only during a window between the late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth that there was a conjuncture between the non-polluted climate and the arrival of the technology of printing in colour. Our attempts to imagine of the ancient lightscape and the way that it impinged on real ancient Athenians as they used the Parthenon and other features of the cityscape therefore relies on the few coloured images made during that window.

It was also only with the advent of printing in colour in a few industrially developed countries in the later nineteenth century that sizable numbers of people were able visually to experience something of the phenomenon at a distance. Although many visitors experienced the microclimate, it could usually be described to others only by the use of words, as many tried to do. Many of the books that carried an allusion to the light in their titles either remained unillustrated or used only black and white.96

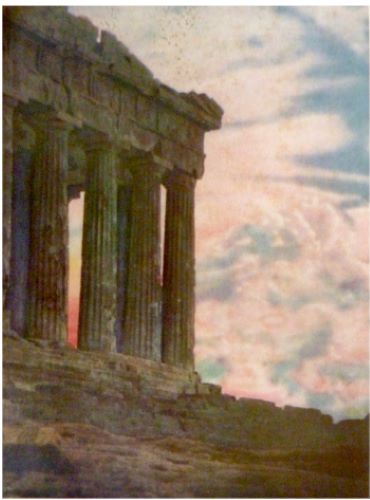

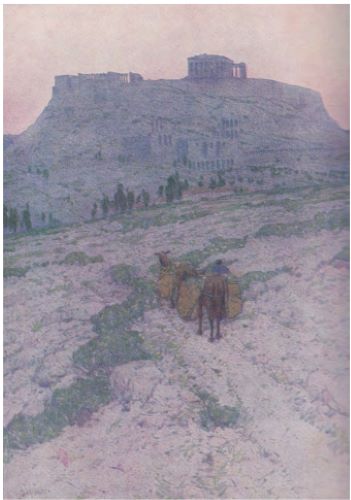

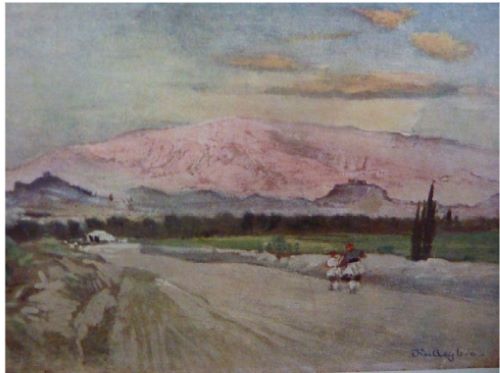

And as the twentieth century advanced, and the air pollution gradually increased, what had once been normal gradually became ever more rare. Paradoxically, the ancient buildings that innumerable viewers of earlier times had described as made of white marble, assuming wrongly that this was their colour in ancient times, are now, as a result of the loss to air pollution of the thin topmost layer (‘epidermis’) of the stone, whiter than they have ever been. For centuries the buildings had presented themselves in a variety of browns, except where the marble had been chipped or struck by gunfire, where it was bright white.97 And the colour experienced by the viewer changed with the changing light, morning and evening, sunlight or moonlight, summer or winter. Sometimes when the sun was strong the Parthenon appeared cream-coloured, at other times violet, almost black.98 It was this effect of the changing light on the marble that the first colour photographers attempted to convey, as shown in the examples that follow. We can also recover something of what had been normal before, including in antiquity, by looking at images made by artists in the window from the 1890s to the 1920s, including the brightness of the light, the purpling mountains, the wild flowers, and the long clear sightlines, as in Figures 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3. Others attempted to carry to others something of the enveloping light as in Figure 1.3.

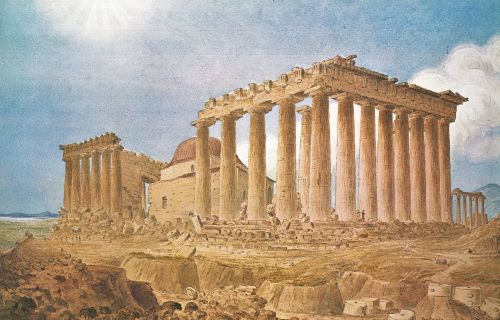

In Figure 1.4, we have an image of how the Parthenon appeared to those approaching in festival procession along the road from Eleusis. They first saw it from a distance as crowning the Acropolis with Hymettus behind, only to disappear from view as they came nearer, and reappear in part when they arrived in front of the entrance on the west side and saw the west pediment.102

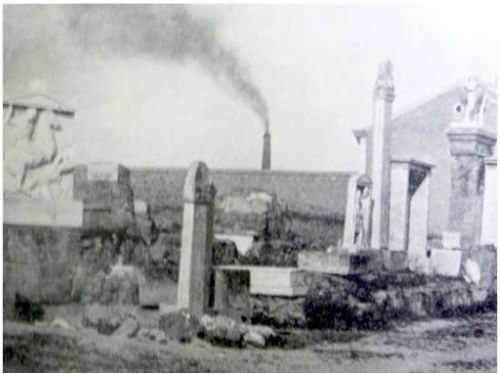

By the end of the nineteenth century, however, there was already a sense that the era when it was possible to experience the same micro-climate as had existed in classical Athens was coming to an end. Athens was now a city of ever encroaching modernity, with industries that polluted the air. A glimpse of the change can be seen in the small photograph shown as Figure 1.5.

The English novelist George Gissing invented a conversation between two friends that picked up their sense of superiority to the Greeks, appropriated from the Roman satirist Juvenal, concerning the changes to the microclimate and the lightscape. Paradoxically, it was at the very time when the pieces of the Parthenon in the British Museum were being scraped white at the behest of Lord Duveen that the then director Sir Frederick Kenyon, who had evidently not looked at them for some time, was praising one of the books that brought out the ‘light and colour and wonderful atmosphere of Athens’, and commending how ‘the clear atmosphere blended and subdued the colours on the marble which in a picture looks exaggerated yet is after all within the truth’.105

It was William Ewart Gladstone, whose periods as British Prime Minister made him one of the most famous men of the nineteenth century, who had first pointed out how variable were the Homeric words for colour. The sky might, he noticed, be described in English translation as ‘violet’ as could the sea, and the hills as ‘purple’ and the sea as ‘wine-coloured’. And what, the question arose, did Homer mean by describing sheep as violet? Were the animals being presented prophetically as carrying wool that would be turned into garments dyed in that colour? Gladstone, who visited Athens in December 1858, had from his knowledge of the Homeric epics already noticed that in these words, as in others, Homer was not concerned with colour as fixed ‘descriptions of prismatic colours or their compounds’, but with the impact of the light on the human who experienced it.106 In northern countries, he wrote, colours in the external world, ‘nature’, mostly changed only slowly. But, in a phrase that showed that he understood that perception is also conditioned by prior consumption of images—in modern terms, by horizons of expectations—he attributed this anachronistic way of seeing to two British national stereotypes of his day, a literalist tendency to force complexity into countable categories, like ‘an auditor in the accounts of some delinquent Joint-Stock Company’.107 He noted that a similar oversimplification was applied to the colours of the Newtonian spectrum. His contemporaries regarded them as qualities fixed, not as events experienced.108 Gladstone’s key observation has since been carried forward, with further evidence, as a persuasive emerging theory, and examples are displayed in colour plates by Adeline Grand-Clément.109 In the world of Homer, colour was, as Gladstone appreciated, an embodied experience, with no sharp boundary expected or experienced between the mind of human viewer and things viewed. And perception and cognition appear to have been regarded and encouraged in the same way during the classical period too. This is to be found, for example, in the images of seeing to be found on vase paintings, which cannot easily be made to fit into the categories of modern representational or allegorical art where a live viewer is assumed to encounter an inert—objectified—object.110 The museum practice of using fixed, sometimes tinted, spotlights is therefore not only a relic of western romanticism and a usurpation of the visitor’s choice, but an obstacle to attempts to look at, or even imagine, objects such as the ‘marbles’ from the Parthenon in the ways that the classical Athenians and their successors encountered them for many centuries.111

Besides the ancient lightscape, much of the visible timescape encountered in classical Athens had also survived into modern times. The Athenians of the classical era, we can be certain, did not regard themselves as living ‘in the youth of the world’, a thought common in the modern centuries.112 Nor did they regard themselves as living in the ‘morning lands of history’.113 At the time that the classical Propylaia, with its astonishing lintel, was built in the classical age, there had been a gateway on the site for around eight hundred years.114 In a long era of almost constant war and internal dissension, they are unlikely to have thought that they had achieved a perfect balance between the body and the soul, the useful and the beautiful, the citizen and the state, and liberty with patriotism, as the archaeologist Ernest Beulé wrote in 1869.115 Nor could they have thought of themselves as living in the ‘dawn of every thing which adorned and ennobled Greece’, as the Select Committee that recommended the purchase of Lord Elgin’s collection of antiquities had declared.116

On the contrary, to judge from the writings of the classical era that have come down to us, they were well aware that they were inhabiting a time that was the outcome of a deep past of which they knew little. Within a day’s march from Athens were the deserted acropolises of Mycenae and Tiryns, which had been built of large irregular blocks of masonry with astonishing skill in pre-historic times by people about whom they knew little. Remnants of the ‘Cyclopean’ structures, as the classical Greeks named them, after the Cyclops, the one-eyed, gentle, vegetarian though not lacto-vegetarian, giant in the Odyssey, were to be found over much of the world that they knew as far as Italy. Huge, well-built monuments, some ruinous, but others with their walls still standing, not only reminded the ancient Athenians of a civilization of which they knew little, but scolded them. How could mere Athenian mortals living in the modernity of the fifth and fourth centuries BCE hope to match the achievements of the predecessors who had performed such feats of building? And why had the men who had built these huge structures disappeared, leaving only the stones and stories of uncertain historicity? The Athenians of the classical era seem also to have had an explicit understanding of the loss even of remembrance, disasters that had struck whole peoples, not only as long-run slow trends of depopulation and abandonment, although they saw these too, but as catastrophes that had occurred at sudden moments in deep time.

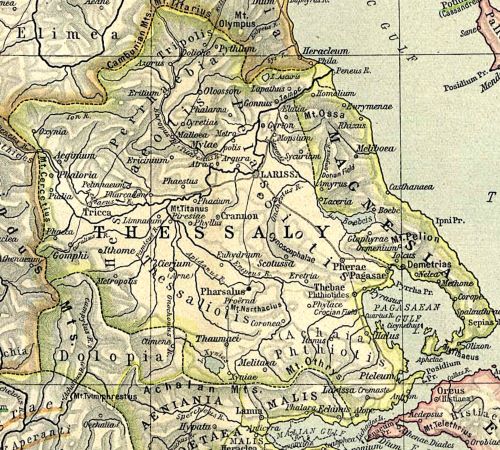

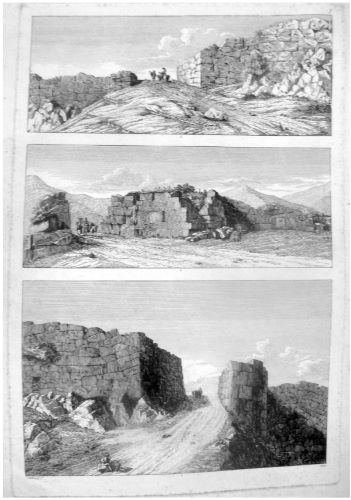

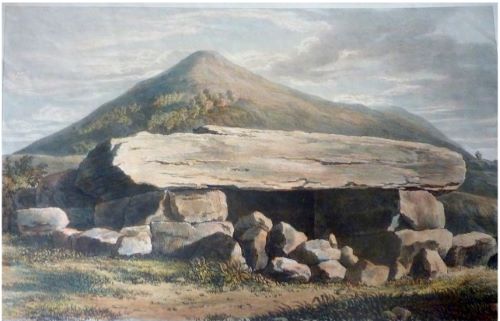

Images of Cyclopean remains as they still existed in the long eighteenth century largely undisturbed since they had apparently been abandoned in some remote past, are given as Figures 1.6 and 1.7.

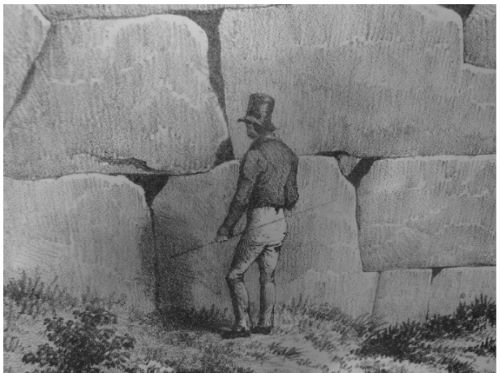

On the scale shown in the caption to the image, the portal was around fifteen English feet long. A glimpse of Edward Dodwell using a rod to measure Cyclopean ruins in Italy is shown in Figure 1.8.

The image incidentally preserves information not only about the skill of the construction but about the measuring rods that were commonly used, with little change until recent times. Although no ancient example has been found, the image enables us to reimagine what was amongst the commonest sights during the building of the classical Parthenon, and was commonly used as a simile not only for exactitude and reliability but for anchoring the imagined to the familiar, and as an image of what was believed and presented as occurring in the act of seeing itself.120

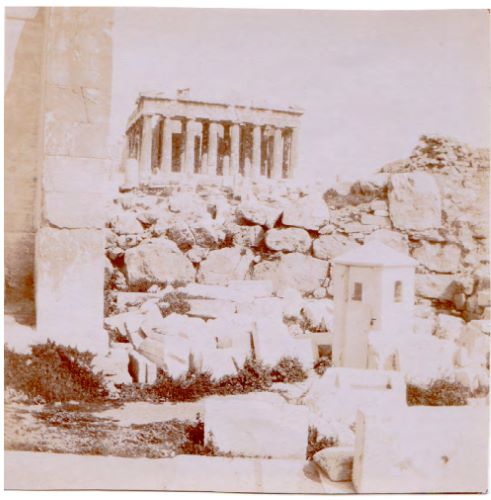

In Athens itself, a fragment of a Cyclopean wall remained to be seen despite the classical-era refashioning of the Acropolis, as was discovered in the nineteenth century. An amateur photograph of unknown date, but taken before the Acropolis summit was cleared, is shown as Figure 1.9.

This Cyclopean wall is, in modern terms, ‘polygonal’ and ‘hammer-dressed’, in construction, although with smaller stones than is normal.122 Whether it was an accidental survival of the Mycenaean-era acropolis from before the Persian destruction of 480, or was purposely preserved as a commemoration or a demonstration of continuity, it anchored the stories to the site, giving credence, at least in the moment of encounter when the imagination was already engaged, to this claim: that the characters who populated the stories displayed on the buildings and re-performed in newly imagined variants in the tragic drama were not entirely fictional, but had actually walked the land.

Together the landscape, the built cityscape, and the lightscape made a storyscape that the western visitors from the seventeenth century onwards immediately recognised from their knowledge of the ancient authors. They also discovered that it had, for local people, been so completely covered over and repurposed by a millennium and a half of imperial Christianization that it had been almost entirely lost from memory. However, since the storyscape was a human construct it could easily be recovered and substituted, as happened apace locally as well as amongst visitors after the Greek Revolution.123 The surviving works of ancient authors, especially the writers of dramatic and dialogic texts, are replete with examples of interactions with the storyscape, including descriptions of how it was used on ceremonial occasions, such as festival processions, as a component of attempts to persuade and to internalize. Visual presentations of the Athenian storyscape are rarer, perhaps because, for the local people who already knew and lived among them, there was no need for the stories to be mediated. An example, which, because it contains explanatory words, may have been intended for export to a place geographically distant from Athens, is shown on an unprovenanced item of ceramic ware (‘skyphos’) as Figure 1.10, flattened in the reproduction so that the whole image is visible to the modern viewer in two dimensions.

In this example, the mute stones are made to speak not only in words set beside the visual image but also by translation into performance, as the stories were listened to, retold, and repeated and the pictures were seen and re-seen as part of an iterative process of making, authenticating, and consolidating a storyscape. By showing mythical figures using measuring rods and lines, the image humanizes them, making it easier for its viewers both to see what were to them familiar objects, and to connect the imagined and invisible world of the gods to the real material world that they experienced.

The educated classes of classical Athens, we can be confident from the remarks made by authors of the time, were both conscious of their deep past and aware of how little they knew about it. Many had some knowledge of what had actually happened (‘anteriority’), although only for the short period that can be held in human family memory without becoming unreliable. Most too had a fairly complete, if patchy, reliable knowledge of a longer anteriority that had been gathered by researches that were undertaken, written up, and preserved by those scholars and historians who placed high value on evidence, observation, and critical reading of primary sources, including ancient inscriptions. However, in the classical period of the fifth and fourth centuries, despite much effort, they found that there was little that could be regularized into calendar time before 776 BCE, the date of the first Olympic games. But the Athenians were also aware of more remote anteriorities about which they knew little other than what might be discerned from a corpus of stories that they preserved, critiqued and queried, added to and subtracted from, and that they presented, performed, and re-performed, of which the story of the birth of Athena was one that they chose to preserve and curate both on the Parthenon, on images inscribed on pottery, in written stories, and perhaps in dramatic performance.

There were overlaps between the categories, especially when attempts were made to reconcile the variations among the stories about deep time and to regularize them into a single narrative within calendar time. Taken together, however, they may still be able to provide us with the conceptual framework that the ancient Athenians themselves, as well as modern evidence-based disciplines, have found most useful in understanding their situation in general and, more particularly, the aims of their own cultural production and consumption, including the Parthenon.

What the eighteenth-century travellers did not recognize, and even today is seldom explicitly noticed, is that alongside the stories of mythic gods and heroes was a modern progressive narrative of how human beings had emerged from brutishness through a series of economic and social step changes to the Athenian city-based democracy in which they lived, as described earlier. And that spoke too of a projected future that, from their fifth-century baseline, had the potential to progress even further in specific identified ways.125

Endnotes

- The question that bothered the eighteenth-century western architects, such as Cockerell, was discussed in St Clair, WStP, Chapter 6, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.06.

- An example of ‘highest point’ was offered by de Moüy, Cte Charles de, Ambassadeur de France à Rome, Lettres Athéniennes (Paris: Plon, 1887), ii, and innumerable others, especially in the late nineteenth century. Like others, de Moüy regarded the changing light and colours as intrinsic to his experience of six years sitting at the foot of the Acropolis and to his opinion on the falsity inflicted on the experience when objects were placed in museums. The phrase, ‘men like ourselves’ had been popularized by J. P. Mahaffy, whose intervention in the debate on removing the Frankish Tower was noted in St Clair, WStP, Chapter 21, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.21, whose numerous popular and scholarly books dominated perceptions of ancient Hellas in the anglophone world for around half a century: ‘The Greek classics are writings of men of like culture with ourselves, who argue with the same logic, who reflect with kindred feelings […] In a word they are thoroughly modern, more modern than the epochs quite proximate to our own’. Mahaffy, Rev. J. P., Social Life in Greece from Homer to Menander (London: Macmillan, 1874), unnumbered page at beginning of Chapter 1. Perhaps under the influence of his pupil Oscar Wilde, Mahaffy confronted many of the differences, including what he called ‘that strange and to us revolting perversion’ pederasty, as well as homoerotic practices, enslavement and routine killing of prisoners. In later editions, perhaps responding to public opinion or pressure from publishers, he rowed back on these passages while maintaining his ’men like ourselves’ claim, in effect crossing the line between applying his knowledge as a scholar and historian, and telling a bland story, which, by selective omission and reassurance, allowed him to continue his career as public intellectual, offering, for example, many comments on Irish politics. Wilde found an opportunity to retaliate at what he regarded as a betrayal when, in reviewing one of Mahaffy’s later works in the Pall Mall Gazette of 9 November 1887, he described his former teacher’s vision of ancient Greece as ‘Tipperary writ large’. The tradition of ‘our debt to Greece and Rome‘ is discussed by Hanink, Johanna, The Classical Debt: Greek Antiquity in an Era of Austerity (Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, Harvard University Press, 2017), https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674978249, and in Zuckerberg, Donna, Not All Dead White Men: Classics and Misogyny in the Digital Age (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018).

- Connelly, Parthenon Enigma, x.

- Discussed in St Clair, WStP, Chapter 5, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.05 and following, including the still unanswered question of why it had not begun centuries earlier during the Frankish period when the Acropolis was frequently visited by eminent classical scholars from Italy.

- Discussed in St Clair, WStP, Chapter 7, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.07 and Chapter 22, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.22.

- Discussed, for example, in St Clair, WStP, Chapter 14, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.14 that pieces together information about those who were enslaved. Chapter 22, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.22, which offers responses from a much wider, though still unrepresentative sample, shows what is normally missing.

- As discussed in St Clair, WStP, Chapters 16, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.16, 17, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.17, 18, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.18, and 19, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.19.

- The 1801 firman, more properly the vizieral letter that provided Elgin’s agents with some cover for their depredations, and the 1806 firman that ordered a cessation, are discussed in Appendix A, WStP.

- As discussed in St Clair, WStP, Chapter 12, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.12, and 13 https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.13. Another incidental effect of the saving of the monument during the Revolution was to destabilize the narrative of ‘saving’ that had been applied to the damage done to the building by Lord Elgin and his agents a generation before, and that led to the attempts to patch up the narrative as discussed in WStP, Chapter 20, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.20.

- Osborne, Robin, ‘Classical Presentism’ in Past and Present, Vol. 234 (1) (2017), 217–226, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtw055.

- As summarized in St Clair, WStP, Chapter 22, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.22. The notion of the eyes as carriers of light, as postulated by the mainstream theory of extramission, is referred to explicitly in Plat. Tim. 45b; and as φωσφόρουςκόραςin Eur. Cycl. 611, a play in which the putting out of the light-bearing cognition of the one-eyed Cyclops by a fire-bearing torch is central to the story, and of which the usual translation, ‘shining’, that is, a quality conferred by an external observer, loses part of the context that an ancient viewer/listener/reader would recognize. Indeed, the numerous references in ancient Greek literature to actual torches as light-bearing, and their frequent use in ritual and in visual presentations of ritual processions (as on the Parthenon frieze) may have carried an implication that, metaphorically, they were like eyes, rather than that, as may also have been true, extramission was derived from the experience of torches.

- The modern science-based understanding, with its vocabulary of ‘saccades’ and ‘salience’ was discussed in St Clair, WStP, Chapter 1, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.01.

- Smith, Martin Ferguson, ‘New Fragments of Diogenes of Oenoanda’ in American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 75 (4) (Oct. 1971), 360, where he quotes ‘an exposition of the Epicurean theory that visions, thoughts, and dreams are caused by effluences from objects […] fine atomic films, similar in shape to the objects from which they emanate, which are emitted in consequence of the vibration of each object’s component atoms.’ I am grateful to Voula Tsouna at whose seminar ’The Method of Multiple Explanations in Epicureanism’ at the Institute of Classical Studies London, 9 November 2020, the topic was discussed.

- As discussed in St Clair, WStP, Chapter 22, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0136.22. An example of how we can identify the presence of such misunderstandings, and use that knowledge to offset their effects, is in Chapter 4 and its discussion of the Parthenon frieze.

- An example is given in Chapter 3.