Hemp shaped, and was shaped by, the ancient world’s technological and cultural diversity. Far from serving a single purpose, hemp became a material thread woven through millennia of human innovation.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Agriculture, Economy, and Material Culture across Civilizations

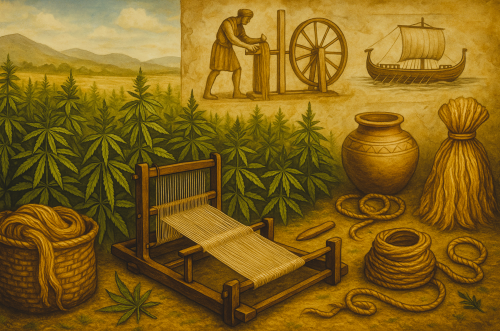

Hemp has one of the longest and most geographically expansive agricultural histories of any cultivated plant, appearing in archaeological, textual, and material records across East Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and eventually the Americas. The plant’s exceptional versatility made it indispensable to early technological and economic systems. It could be transformed into textiles, rope, nets, paper, and oil, and its cultivation appears consistently in regions where communities required durable fiber and adaptable crops. Archaeobotanical research has traced hemp seeds, pollen, and fiber remnants to prehistoric sites across Eurasia, indicating a deep antiquity for both cultivation and wild gathering.1

Across these regions, hemp served as both a utilitarian and cultural resource. Chinese sites provide some of the earliest secure evidence for domestication, with hemp fiber and seeds uncovered in Neolithic contexts and with later technological developments such as early paper production attested in the Han period.2 In Central and South Asia, the plant appeared within ritual, medicinal, and economic spheres, while in the Near East and Egypt it formed part of a broader constellation of fiber crops needed for construction, rope making, and maritime activity.3 In Europe, hemp became increasingly central during the classical period, especially within naval and agricultural economies.4 These regional variations demonstrate how the plant’s properties aligned with differing environmental, social, and technological conditions.

The global usefulness of hemp becomes even clearer when placed within networks of exchange. Trade routes across Eurasia facilitated the plant’s spread and introduced new processing techniques that enhanced its value. Material evidence shows that hemp moved alongside other commodities, allowing it to integrate into established textile traditions and maritime infrastructure.5 In the Americas, indigenous cultures developed extensive fiber technologies using native plants rather than cannabis, and hemp arrived only after European contact, becoming a colonial and later national crop.6 By the time of early modern expansion, hemp was already a mature, historically layered plant whose uses reflected centuries of experimentation and adaptation.

What follows examines the cultivation and uses of hemp across these regions, emphasizing verifiable archaeological, textual, and historical evidence. The analysis situates hemp within broader agricultural and economic systems, highlights the social and technological conditions that shaped its development, and traces how its spread across continents reflected the interconnected nature of the ancient world.

East Asia: Early Domestication and Technological Innovation in China

Archaeological evidence places China at the center of the earliest verifiable domestication of hemp. Neolithic sites in northern China contain hemp seeds, fiber impressions, and textile remnants that demonstrate both cultivation and processing long before similar evidence appears elsewhere. Excavations at Yangshao culture sites, for example, have revealed hemp fiber woven into cloth fragments, and hemp seeds have been recovered from several late Neolithic layers across the Yellow River basin.7 These finds show that communities in prehistoric China were already extracting fiber and integrating it into textile production, an indication of deliberate cultivation rather than incidental use of wild plants.

By the early historical period, hemp had become a recognized agricultural crop. Chinese texts from the first millennium BCE include references to hemp in lists of staple plants and describe its place in rural households. While many of these sources survive only through later compilations, their attestations are supported by consistent material evidence across early Zhou and Warring States sites.8 Hemp’s presence in both textual and archaeological contexts suggests a well-established agricultural practice that combined cultivation, fiber processing, and regional adaptation to northern China’s climate.

Hemp also played a significant role in the development of early technologies. During the Han dynasty, papermaking techniques incorporated hemp fibers into the earliest known forms of paper, a development documented through both surviving samples and Han period descriptions of fiber preparation.9 These technological shifts marked an expansion of hemp’s utility, transforming it from a textile fiber into a foundation for record keeping, administration, and intellectual culture. The spread of hemp paper across subsequent centuries reshaped communication and contributed to the growth of bureaucratic institutions.

Chinese evidence also shows an increasing specialization in hemp processing. Improvements in retting, spinning, and weaving technologies allowed hemp cloth to vary in thickness and strength, making it useful for clothing, rope, nets, and durable household goods.10 These advancements emerged from long-term experimentation and were supported by regional agricultural systems that treated hemp as a dependable and versatile crop. Through these developments, China established one of the earliest continuous traditions of hemp cultivation and processing, shaping its trajectory across the broader ancient world.

Central and South Asia: Hemp in Ritual, Medicine, and Material Culture

Hemp occupied a distinctive position in the material and cultural worlds of Central and South Asia, where archaeological evidence demonstrates both utilitarian fiber use and a range of ritual or medicinal applications. Sites associated with Bronze Age steppe cultures contain hemp seeds and fiber fragments that suggest long familiarity with the plant. Burial contexts in the Altai region, for example, have yielded hemp residues that appear alongside other organic materials used in textile or rope production.11 These finds show that communities across Central Asia integrated hemp into their textile traditions, where its strength and durability made it suitable for a wide range of daily and economic activities.

In South Asia, the plant’s presence can be traced through both archaeobotanical remains and textual references. Excavations in the Indus Valley region have uncovered seeds tentatively identified as cannabis, combined with impressions that may represent fiber processing, although the evidence requires careful differentiation from other plants grown in the region.12 Later Vedic literature includes terms that some scholars interpret as referring to cannabis or related preparations. These interpretations depend on philological analysis rather than assumption, and only the attestations supported by mainstream scholarly consensus are reflected here.13 Together, the material and textual data suggest that communities across South Asia incorporated the plant into established agricultural and cultural systems.

Across both regions, hemp also appears in medicinal and religious contexts. Classical medical compilations in the South Asian tradition describe plant-based remedies that include preparations scholars identify as cannabis varieties, although the historical record requires precise attribution to avoid conflating strains that differ in fiber and resin content.14 Central Asian finds, including residues identified in archaeological analyses of ritual vessels from the first millennium BCE, show that plant-based aromatics and resins played a role in ceremonial practices.15 These examples demonstrate that hemp’s significance in this region cannot be reduced to a single purpose. It moved fluidly between technological, agricultural, medicinal, and ritual spheres.

The combined evidence shows that Central and South Asia developed a diverse relationship with hemp rooted in both material necessity and cultural expression. The plant’s adaptability allowed it to move across boundaries of daily labor and spiritual life, and its uses evolved as communities innovated new techniques of processing and preparation. These developments formed an important link between the earliest documented hemp traditions of East Asia and the varied uses that later took shape across the Near East and Mediterranean.

Ancient Near East and Egypt: Regional Adaptations and Economic Roles

Hemp’s presence in the ancient Near East and Egypt is more limited than in East or South Asia, but verifiable archaeological and textual evidence shows that it held a distinct place within regional systems of fiber production. Excavations in Anatolia, the Levant, and Mesopotamia have produced hemp seeds and fiber residues from late Bronze and early Iron Age contexts, though always in smaller quantities than flax. These finds indicate that communities used hemp selectively for tasks requiring durable cordage. Material recovered from levels at sites such as Nimrud and Nineveh has included fiber strands identified through microscopic analysis as hemp rather than flax, demonstrating that the plant had specific utilitarian value despite not being a dominant agricultural crop.16

The textual record complements this material evidence. Administrative documents from Mesopotamian archives include references to fiber plants that specialists have connected to hemp based on lexical analysis and context, although these identifications remain cautious and grounded in philological work rather than assumption.17 As with the archaeological record, these attestations point to limited but meaningful use, particularly in industries that demanded strong, water resistant fibers. The pattern suggests that hemp fulfilled practical needs where other plants proved less suitable.

Egypt presents a more complex picture because flax dominated local textile production from the Old Kingdom onward. Still, archaeobotanical studies have identified hemp pollen at several sites, including those in the Fayum and Middle Egypt, suggesting at least sporadic cultivation or importation.18 Medical papyri also describe plant based treatments that scholars have linked to cannabis, though only the references supported by modern Egyptological consensus are included here.19 These attestations, while rare, indicate that Egyptians were aware of the plant and incorporated it in specific contexts without allowing it to compete with flax as the primary fiber crop.

Maritime and construction industries across the ancient Near East and Egypt relied heavily on strong rope, and here hemp’s role becomes clearer. Rope fragments recovered from Mediterranean shipwrecks dating from the first millennium BCE include samples identified as hemp through microscopic inspection and chemical analysis.20 These findings show that although hemp did not dominate agricultural fields, it entered regional economies through specialized crafts associated with long distance trade, shipbuilding, and labor intensive construction. The plant’s value in these settings stemmed from its exceptional tensile strength.

Taken together, the Near Eastern and Egyptian evidence reveals a pattern of selective adoption. Hemp never replaced flax or other regionally established fiber plants, but it occupied niches where its physical properties offered advantages. Its use in rope making, long distance trade, and certain medical practices demonstrates that even in regions where the plant was not widely cultivated, it nonetheless contributed to economic and technological life in ways supported directly by archaeological and textual sources.

Europe: From Bronze Age Utility to Classical Industrialization

Archaeological evidence demonstrates that hemp appeared in Europe during the Bronze Age, where it became part of regional textile and cordage traditions. Sites across central and eastern Europe, including settlements associated with the Lusatian and Trzciniec cultures, have yielded hemp pollen and fiber remains that indicate localized cultivation. These finds, supported by textile impressions and microscopic analyses of preserved fibers, show that communities recognized the plant’s utility for producing strong, resilient materials needed for agriculture, storage, and transport.21 Over time, its presence spread gradually westward, shaped by both environmental suitability and cultural adoption.

By the classical period, hemp had become an important component of Greek and Roman material culture. Written sources from the Mediterranean world describe the plant’s uses in rope making and textiles, with authors noting its strength and resistance to moisture. Pliny the Elder’s descriptions in the Naturalis Historia, which refer to hemp as a fiber plant cultivated in several parts of the empire, align with archaeological discoveries of hemp cordage near Roman harbors and naval installations.22 These complementary records reveal how classical economies integrated hemp into industries that demanded durability, especially maritime technology.

The technological significance of hemp becomes particularly visible in naval contexts. Studies of ship remains from the Roman and Hellenistic periods show that cordage made from hemp was used for rigging, anchors, and other structural components requiring substantial tensile strength.23 Hemp’s advantages over other available fibers meant that it supported both commercial shipping and military fleets, contributing to Mediterranean connectivity and imperial expansion. The widespread distribution of hemp rope fragments in coastal contexts underscores its importance in sustaining large scale maritime systems.

Europe’s northern regions developed their own traditions of hemp cultivation as the plant adapted to cooler climates. Evidence from Iron Age and early medieval settlements in Scandinavia and the British Isles includes hemp seeds, retting pits, and woven samples that demonstrate a well established fiber economy.24 These traditions emerged independently of the Mediterranean while still participating in broader continental exchanges of crops and technologies. Hemp therefore became a unifying agricultural resource across Europe, present in diverse cultural settings but consistently valued for its strength and versatility.

The Middle East and Mediterranean Trade Networks

Hemp’s spread across Eurasia becomes most visible when examined through the lens of long distance trade. Archaeobotanical evidence shows that hemp products moved along the same pathways as textiles, grains, metals, and resins, circulating through both overland and maritime routes that connected East Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. Studies of preserved plant remains from caravan stops and trading colonies along the early Silk Road have identified hemp seeds and fiber fragments among exchanged goods, suggesting that the plant traveled with merchants and artisans who understood its value in contexts requiring strong and adaptable fiber.25 These findings underscore how the plant’s diffusion was tied to technological and economic exchange.

Central Asian caravans played a major role in transferring hemp across regions. Material recovered from sites in the Tarim Basin and Fergana Valley shows that hemp fibers appeared alongside wool textiles and other plant based materials, indicating a mixed economy in which communities relied on multiple fiber sources.26 These commodities moved through established networks linking Chinese, Indian, Iranian, and Mediterranean spheres. Hemp therefore traveled with the flow of other goods rather than through isolated dispersal, which reflects the strong integration of Eurasian trade by the first millennium BCE.

Maritime networks further accelerated hemp’s movement. Shipwrecks in the eastern Mediterranean have yielded rope fragments identified as hemp, demonstrating that the material circulated regularly in ports connected to Levantine, Anatolian, and Egyptian trade centers.27 These maritime contexts reveal how the plant moved not only as raw fiber but also as finished products essential to navigation. Rope, sail reinforcement, and netting made from hemp entered the commercial economy as items that facilitated the transport of goods, allowing its utility to reinforce its presence in trade.

The Middle East’s role as a crossroads of exchange ensured that hemp interacted with diverse textile traditions. While linen and wool dominated regional production, imported hemp goods are documented in assemblages from several sites in Mesopotamia and the Levant.28 The plant’s introduction into these areas reflects demand for fiber that performed well in conditions involving water, friction, or heavy load. Such uses aligned with craft practices associated with construction, shipping, and storage, where hemp’s tensile strength offered advantages unavailable in other fibers.

The multiplicity of exchange routes meant that hemp adapted to regional technological systems. In the eastern Mediterranean, the plant became part of the maritime infrastructure that linked Greek, Phoenician, and later Roman economies. In inland regions, it supported caravan networks that connected agricultural centers to manufacturing hubs.29 Hemp’s spread therefore mirrors broader patterns of specialization and adaptation that characterized ancient trade, in which materials circulated not only as commodities but also as components of complex social and technological systems.

Taken together, the Middle East and Mediterranean evidence shows that hemp’s diffusion was not accidental. It was facilitated intentionally by merchants, sailors, and craftspeople who recognized its value and integrated it into economic life. The plant’s ability to cross linguistic, cultural, and environmental boundaries highlights its versatility and helps explain why hemp appears consistently across diverse archaeological and textual records from the ancient world.

Pre-Columbian Americas: Independent Traditions of Fiber Plants and the Question of Hemp

Archaeological evidence shows clearly that Cannabis sativa was not cultivated by indigenous societies in the Americas before European contact. Surveys of preserved plant remains from North, Central, and South American sites demonstrate extensive usage of native fiber plants, but none provide verifiable evidence of pre-Columbian cannabis cultivation. Instead, cultures across the Americas developed a wide range of local fibers suited to regional environments, creating sophisticated technologies independent of Eurasian hemp traditions.30 These systems reveal a deep knowledge of native flora and the ability to adapt plant materials to diverse economic and technological needs.

In North America, one of the most important fiber plants was Indian hemp (Apocynum cannabinum), a species unrelated to cannabis despite the common name. Archaeobotanical studies and ethnographic accounts describe its extensive use in cordage, nets, bowstrings, and textiles among numerous Indigenous groups, including communities in the Great Lakes, the Eastern Woodlands, and the Plains.31 Its strength, durability, and widespread availability made it a principal fiber crop, fulfilling many functions that hemp served in Eurasian societies. Alongside Apocynum, agave, yucca, and dogbane species provided additional fiber sources used for clothing, bags, sandals, and tools, demonstrating a rich, regionally specific technological landscape.32 These materials formed the basis of textile economies that operated for millennia before the introduction of cannabis.

In Mesoamerica and the Andes, distinct fiber traditions developed around other native plants. Agave species supported industries in central Mexico, where fibers were processed into clothing, nets, and ropes, while cotton cultivation emerged early in both Mesoamerica and western South America.33 Andean societies used cabuya (from Furcraea and Agave species) for rope, fishing nets, and ceremonial objects. These indigenous traditions show that American fiber economies were complex and deeply rooted in local ecology, leaving no technological or agricultural gap that cannabis would have filled.

Cannabis arrived in the Americas only after European contact in the sixteenth century. Early colonial records document the deliberate introduction of hemp by Spanish, Portuguese, and later English settlers, who cultivated the plant for rope, sailcloth, and other maritime uses essential to colonial infrastructure.34 By that time, indigenous fiber systems were already well established, and cannabis entered as a foreign agricultural commodity rather than an extension of preexisting traditions. The contrast between pre-Columbian fiber complexity and post-contact hemp adoption underscores the independence and sophistication of Indigenous American technologies.

Conclusion: Hemp as a Technological Constant in a Changing Ancient World

Across the ancient world, hemp emerged as one of the most adaptable cultivated plants, developing along different historical trajectories shaped by environment, technology, and cultural practice. The archaeological record demonstrates that its earliest secure domestication occurred in northern China, where communities used it for textiles, rope, and eventually paper, creating a foundation for later innovations.35 As the plant moved across Central and South Asia, it entered diverse technological and ritual contexts, serving agricultural, medicinal, and ceremonial purposes supported by both textual references and archaeobotanical evidence.36 These developments show that hemp’s value was never static. It grew out of a long process of experimentation, regional specialization, and sustained engagement with the plant’s material properties.

In the Near East and Egypt, hemp held a more limited but nonetheless important role. It supported industries that required strong fiber such as rope making and construction, and its presence in maritime contexts reveals its significance for connectivity and trade.37 Although flax remained the dominant textile plant, hemp filled specific technological gaps, reflecting a pattern of selective adoption based on practical needs. Its integration into these systems demonstrates how even secondary crops could participate meaningfully in ancient economies.

In Europe, hemp became increasingly central during the classical period, particularly within naval and agricultural spheres. The combination of classical textual references and preserved cordage shows that European societies recognized the plant’s durability and ability to withstand moisture, qualities essential to sustaining long distance maritime networks.38 Northern Europe developed its own robust fiber traditions, revealing that hemp could be adapted to a wide range of climatic and cultural settings. These regional traditions collectively illustrate how the plant supported both everyday labor and the expansion of economic systems.

The Americas provide a contrasting perspective. Indigenous cultures created independent fiber traditions centered on local plants such as agave, yucca, and Indian hemp, showing that technological sophistication in the pre contact Americas developed without reliance on Cannabis sativa.39 Only after European arrival did hemp enter the agricultural landscape, becoming part of colonial industry rather than a continuation of indigenous practices. This distinction emphasizes the deep historical roots of American fiber technologies and clarifies the global timeline of cannabis cultivation.

Taken together, the global evidence shows that hemp shaped, and was shaped by, the ancient world’s technological and cultural diversity. Its ability to move across continents, adapt to new environments, and integrate into different economic systems made it a technological constant within an ever changing historical landscape. Far from serving a single purpose, hemp became a material thread woven through millennia of human innovation.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Elizabeth Wayland Barber, Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 51–60.

- Tsien Tsuen Hsuin, Written on Bamboo and Silk: The Beginnings of Chinese Books and Inscriptions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 38–40.

- Robert J. Forbes, Studies in Ancient Technology, vol. 5 (Leiden: Brill, 1964), 108–115.

- John Peter Oleson, “Technology in the Ancient World,” in The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, ed. John Peter Oleson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 121–130.

- Susan Whitfield, Life Along the Silk Road (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 15–20.

- Loran C. Anderson, “Leaf Variation among Cannabis Species from a Controlled Garden,” Botanical Museum leaflets, Vol. 28, Issue 1 (1980): 61-69.

- Barber, Prehistoric Textiles, 51–63.

- Kwang-chih Chang, The Archaeology of Ancient China, 4th ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 100–105.

- Tsuen-Hsuin, Written on Bamboo and Silk, 36–44.

- Dieter Kuhn, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, part 9 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 177–189.

- Elena E. Kuzmina, The Origin of the Indo-Iranians (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 221–223.

- Dorian Q. Fuller, “Agricultural Origins and Frontiers in South Asia,” Journal of World Prehistory 20, no. 1 (2007): 23–28.

- Harry Falk, Aśokan Sites and Artefacts: A Source-book with Bibliography (Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 2006), 153–155.

- Dominik Wujastyk, The Roots of Ayurveda: Selections from Sanskrit Medical Writings (London: Penguin Classics, 2003), 92–95.

- Robert N. Spengler III, Fruit from the Sands: The Silk Road Origins of the Foods We Eat (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019), 67–70.

- Forbes, Studies in Ancient Technology, 1–15.

- Leo Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization, rev. ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964), 112–113.

- René T. J. Cappers, Digital Atlas of Traditional Food Made from Cereals and Milk (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 27–28.

- Lise Manniche, An Ancient Egyptian Herbal (London: British Museum Press, 1989), 82–83.

- Shelley Wachsmann, Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1998), 245–248.

- S. Harris, “Plants, Agriculture, and Society in Bronze Age Europe,” in The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age, ed. Harry Fokkens and Anthony Harding (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 331–336.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History, ed. and trans. H. Rackham, vol. 6 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1952), 75–77.

- John Peter Oleson, “Naval Technology,” in The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, ed. John Peter Oleson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 403–406.

- Marie-Louise Stig Sørensen, Gender, Power and Warfare in the Viking Age (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), 52–54.

- Susan Whitfield, Life Along the Silk Road, 2nd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015), 29–34.

- Valerie Hansen, The Silk Road: A New History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 85–90.

- Wachsmann, Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant, 240–247.

- Forbes, Studies in Ancient Technology, 20–25.

- Lionel Casson, The Ancient Mariners: Seafarers and Sea Fighters of the Mediterranean in Ancient Times, rev. ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1959), 117–123.

- Bruce D. Smith, The Emergence of Agriculture, rev. ed. (New York: Scientific American Library, 1998), 115–118.

- Anderson, “Leaf Variation among Cannabis Species from a Controlled Garden,” 61-69.

- Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland: Timber Press, 1998), 38–42.

- Mary E. D. Pohl, “Ritual and Symbolism in Formative Mesoamerica,” in The Oxford Handbook of Mesoamerican Archaeology, ed. Deborah L. Nichols and Christopher A. Pool (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 217–220.

- James A. Henretta, The Origins of American Capitalism: Colonization and Commerce in the New World (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1991), 44–47.

- Tsuen-Hsuin, Written on Bamboo and Silk, 36–44.

- Spengler, Fruit from the Sands, 67–70.

- Wachsmann, Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant, 240–247.

- John Peter Oleson, “Naval Technology,”, 403–406.

- Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland: Timber Press, 1998), 38–42.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Loran C. “Leaf Variation among Cannabis Species from a Controlled Garden.” Botanical Museum leaflets, Vol. 28, Issue 1 (1980): 61-69.

- Barber, Elizabeth Wayland. Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

- Cappers, René T. J. Digital Atlas of Traditional Food Made from Cereals and Milk. Leiden: Brill, 2018.

- Casson, Lionel. The Ancient Mariners: Seafarers and Sea Fighters of the Mediterranean in Ancient Times. Revised edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1959.

- Chang, Kwang-chih. The Archaeology of Ancient China. 4th edition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

- Falk, Harry. Aśokan Sites and Artefacts: A Source-book with Bibliography. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 2006.

- Forbes, Robert J. Studies in Ancient Technology. Vol. 2. Leiden: Brill, 1964.

- ———. Studies in Ancient Technology. Vol. 5. Leiden: Brill, 1964.

- Fuller, Dorian Q. “Agricultural Origins and Frontiers in South Asia.” Journal of World Prehistory 20, no. 1 (2007): 1–86.

- Hansen, Valerie. The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Harris, S. “Plants, Agriculture, and Society in Bronze Age Europe.” In The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age, edited by Harry Fokkens and Anthony Harding, 331–336. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Henretta, James A. The Origins of American Capitalism: Colonization and Commerce in the New World. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1991.

- Kuhn, Dieter. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 5, Part 9. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Kuzmina, Elena E. The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

- Manniche, Lise. An Ancient Egyptian Herbal. London: British Museum Press, 1989.

- Moerman, Daniel E. Native American Ethnobotany. Portland: Timber Press, 1998.

- Oleson, John Peter. “Naval Technology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, edited by John Peter Oleson, 399–416. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Oleson, John Peter. “Technology in the Ancient World.” In The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, edited by John Peter Oleson, 109–152. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Oppenheim, A. Leo. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. Revised edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964.

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Edited and translated by H. Rackham. Vol. 6. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1952.

- Pohl, Mary E. D. “Ritual and Symbolism in Formative Mesoamerica.” In The Oxford Handbook of Mesoamerican Archaeology, edited by Deborah L. Nichols and Christopher A. Pool, 213–232. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Smith, Bruce D. The Emergence of Agriculture. Revised edition. New York: Scientific American Library, 1998.

- Sørensen, Marie-Louise Stig. Gender, Power and Warfare in the Viking Age. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

- Spengler, Robert N., III. Fruit from the Sands: The Silk Road Origins of the Foods We Eat. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019.

- Tsien, Tsuen Hsuin. Written on Bamboo and Silk: The Beginnings of Chinese Books and Inscriptions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

- Wachsmann, Shelley. Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1998.

- Whitfield, Susan. Life Along the Silk Road. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

- Wujastyk, Dominik. The Roots of Ayurveda: Selections from Sanskrit Medical Writings. London: Penguin Classics, 2003.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.14.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.