The Royal Game of Ur 2600 BC

By Peter Attia

DiceyGoblin

Within the past few years board games have gone through an explosion of growth. In 2012 The Guardian went as far as dubbing it “A Golden Age for Board Games”, stating board games have seen a growth rate as high as 40% year over year. That’s higher than Google, which sees about 20% growth year over year.

The budding interest has also inspired Wil Wheaton and Felicia Day to start a popular Youtube series, called Table Top. This series pits internet celebrities against each other and garners several hundred thousand views per video.

So, how did something so archaic become so popular? Where did it all start?

The First Board Game

(5000 BC)

Most people don’t realize board games are actually pre-historic, meaning we had board games before we had written language. So, what was the very first game?.. Dice! A piece that’s essential in most board games today was the basis of humanity’s oldest games.

A series of 49 small carved painted stones were found at the 5,000-year-old Başur Höyük burial mound in southeast Turkey. These are the earliest gaming pieces ever found. Similar pieces have been found in Syria and Iraq and seem to point to board games originating in the Fertile Crescent. The Crescent is comprised of regions around the Nile, Tigris, and Euphrates River in the Middle East. The same region that invented booze, papyrus, breath mints, and calendars, which are also required when planning your game night!

Other early origin dice games were created by painting a single side of flat sticks. These sticks would be tossed in unison and the amounted of painted sides showing, would be your “roll”. Mesopotamian dice were made from a variation of materials, including carved knuckle bones, wood, painted stones, and turtle shells.

Mesopotamian Four Sided Dice and Stick Dice

Knuckle Bone Dice 5-3rd Century BC from Greece/Thrace

Dice were eventually made from a large variety of materials, including brass, copper, glass, ivory, and marble. Dice from the Roman Era look very similar to the six-sided dice we’re used to today. There were also dice with cut corners (as seen in the image above), giving additional possibilities. They’re similar to high number dice from D&D and other roleplaying games.

Board Games Become a Royal Pastime

(3100 BC)

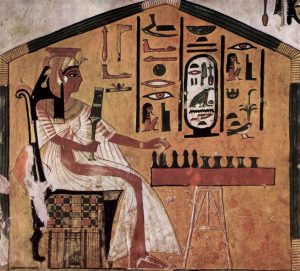

Board games became popular among pharaohs in Ancient Egypt. Primarily, the game of Senet. The game has been found in predynastic and First Dynasty burials. Senet is featured in several illustrations from Ancient Egyptian tombs. By the time of the New Kingdom in Egypt (1550–1077 BC), it had become a kind of talisman for the journey of the dead.

Ancient Egyptians were strong believers in the concept of “Fate”. It’s thought that the high element of luck in the game of Senet were strongly tied to this concept. It was believed a successful player was under the protection of the major gods of the national pantheon: Ra, Thoth, and sometimes Osiris. Consequently, Senet boards were often placed in the grave alongside other useful objects for the dangerous journey through the afterlife. The game is even referred to in Chapter XVII of the Book of the Dead.

As far as gameplay, there is some debate. The Senet board itself is a grid of 30 squares, arranged in three rows of ten. There are two sets of pawns (at least five of each and, in some sets, more, as well as shorter games with fewer). Historians have made educated guesses for the actual rules of gameplay for Senet, which have been adopted by different companies which make sets for sale today.

Board Games Get Tied into Religion

(3000 BC)

With the popular growth of board games amongst royalty, they quickly became adopted by the working class. Soon after, they became tied into religious beliefs. One such game being Mehen.

While a complete set of rules on how to play the game have never been found, we do know the game represents the deity Mehen. The Sun Cult envisioned the god Mehen as a huge serpent who wrapped the Sun God Re in its coils (the game board itself mimics this).

At some point, perhaps even before the Old Kingdom, the game and the god became intertwined. The game became more than just a simple pastime. It instead became synonymous with the serpent deity in texts and thought. Tim Kendall, an Ancient Egyptian Historian, believed it wasn’t possible to know (with the available evidence) whether this deity was inspired by the game itself or an already existing mythology.

A Lion Game Piece from Mehen

While no rules for Mehen have been discovered, a similar Arab game, known as the Hyena Game, shared several characteristics. Because of this, the game play utilized in the Hyena game has been adapted to fit the game of Mehen.

Players each begin with six marbles and one lion. Stick dice as depicted above determine movement. Players start at the tail, along the outer edge of the board, and move towards the center where the snake’s head rests. The players race to the center with their marble pieces. Once a marble reaches center, movement reverses and players move towards the start again. The lion piece is then put into play. This predatory piece is used to capture (eat) an opponent’s marble pieces.

The First Evidence of Humanity’s Longest Running Board Game

(2650 BC)

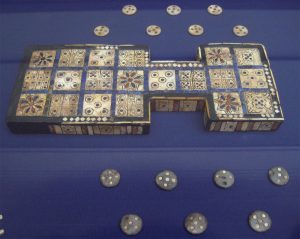

Many people think Backgammon has been played the longest out of all board games, however it’s actually The Royal Game of Ur.

The game had been thought long-dead, superseded by backgammon 2000 years ago. However, game enthusiast Irving Finkel discovered the game’s rules carved into an ancient stone tablet. He then spotted a surprising photograph of an identical game board from modern India. Soon after, Finkel met a retired schoolteacher who had played the same game as a kid. This makes The Royal Game of Ur the game that has been played longer than any other in world history.

The game gets its name from its founding within the Royal Tombs of Ur in Iraq. There was also a set found in Pharaoh Tutankhamen’s tomb. The Royal Game of Ur was played with two sets, one black and one white, of seven markers and three tetrahedral dice (4-sided dice).

The First Evidence of Backgammon

(2000 BC)

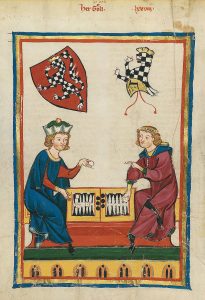

Ludus duodecim scriptorum was a board game popular during the time of the Roman Empire. The name translates as “game of twelve markings”, likely referring to the three rows of 12 markings found on surviving boards. The game tabula is thought to be a descendant of this game, and both are similar to modern backgammon.

XII scripta board in the museum at Ephesus

The oldest game with rules known to be nearly identical to backgammon described it as a board with the same 24 points, 12 on each side. As today each player had 15 checkers and used cubical six-sided dice. The object of the game, to be the first to bear off all of one’s checkers, was also the same. The only differences with modern backgammon were the use of an extra die (three rather than two) and the starting of all pieces off the board. Instead they entered in the same way that pieces on the bar enter in modern backgammon.

The popularity of backgammon surged in the mid-1960s, in part due to the charisma of Prince Alexis Obolensky who became known as “The Father of Modern Backgammon”. He co-founded the International Backgammon Association, which published a set of official rules. He also established the World Backgammon Club of Manhattan, which devised a backgammon tournament system in 1963. He later organized the first major international backgammon tournament in March, 1964, which attracted royalty, celebrities and the press.

The game became a huge fad and was played on college campuses, in discothèques and at country clubs. People young and old all across the country dusted off their boards and checkers. Cigarette, liquor, and car companies began to sponsor tournaments and Hugh Hefner held backgammon parties at the Playboy Mansion. Backgammon clubs were formed and tournaments were held, resulting in a World Championship, which was promoted in Las Vegas in 1967.

Most recently, the United States Backgammon Federation (USBGF) was organized in 2009 to repopularize the game in the United States. Board and committee members include many of the top players, tournament directors, and writers in the worldwide backgammon community.

The Influence of War Inspires Military Strategy Games

(1300 BC)

Ludus latrunculorum was a two-player strategy board game played throughout the Roman Empire. It has references as early as Homer’s time and is said to resemble chess. Because of the limited sources, reconstruction of the game’s rules is difficult, but is generally accepted to be a game of military tactics. Because of the large number of wars during 13th century BC, it’s believed this was the influence on the games theme of military strategy.

The game has many pieces and is played on a checkerboard type pattern. The board is called the “city” and each piece is called a “dog”. The pieces are of two colors, and the art of the game consists in taking a piece of one color by enclosing it between two of the other color.

It’s theorized Ludus latrunculorum may have had an influence on the historical development of early Chess, particularly the movement of the pawns. When chess came to Germany, the terms for “chess” and “check” (which had originated in Persian) entered the German language as Schach. But Schach was already a native German word for robbery. As a result, ludus latrunculorum was often used as a medieval Latin name for chess.

Board Games Become Part of Childhood

(500 BC)

Board games were primarily played by adults in ancient cultures and with their deep roots in society, were quickly adopted by children. Although not technically a board game, one of the first games centered towards kids was Hop-Scotch. That’s right, it’s much older than you thought!

The first references of Hop-Scotch date back to Roman Children around 500 BC. There are many variations of the game all over the world, but the general rules stay consistent. The first player tosses the marker (typically a stone, coin, or bean bag) into the first square. The marker must land completely within the designated square and without touching a line or bouncing out. The player then hops through the course, skipping the square with the marker in it.

The game’s first recorded references in English-speaking world date back to the late 17th century, usually under the name “scotch-hop” or “scotch-hopper”. According to the Oxford English Dictionary the etymology of hopscotch is a formation from the words “hop” and “scotch”, the latter in the sense of “an incised line or scratch”

Board Games Influence Over Eastern Culture

(400 BC)

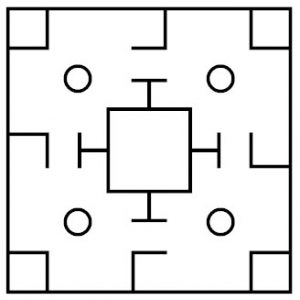

While board games were in Asian society long before 400 BC, they were largely interpretations of Middle Eastern games. Liubo was the first board game to break this habit (followed shortly after by “Go”) to become the first game developed by the Eastern world.

The game was played by two players. It is believed each player had six game pieces that were moved around the points of a square game board that had a distinctive, symmetrical pattern. Moves were determined by the throw of six dice sticks.

Liubo was immensely popular during the Han Dynasty and rapidly declined afterwards. It’s speculated this may have been caused by the rise in popularity of the game of Go. Liubo almost became totally forgotten. Knowledge of the game increased in recent years with archeological discoveries of Liubo game boards and pieces in ancient tombs.

Liubo boards and game pieces are often found as grave goods in tombs from the Han Dynasty. The game boards were made from a variety of materials: slabs of stone, carved wood, or long legged tables with boards built into them and accompanied by bronze pieces. The common feature of all Liubo boards is the distinctive pattern carved or painted on their surface.

In many of the excavated Liubo game boards, only certain pieces survived. Since some pieces are made of organic material, like wood, they’d rot away. However, they found a whole friggin set in 1973 that was well preserved!

The set contained the following pieces:

- 1 lacquered wooden game box (45.0 × 45.0 × 17.0 cm.)

- 1 lacquered wooden game board (45.0 × 45.0 × 1.2 cm.)

- 12 cuboid ivory game pieces (4,2 × 2.2 × 2.3 cm.), six black and six white

- 20 ivory game pieces (2.9 × 1.7 × 1.0 cm.)

- 30 rod-shaped ivory counting chips (16.4 cm. long)

- 12 ivory throwing rods (22.7 cm. long)

- 1 ivory knife (22.0 cm. long)

- 1 ivory scraper (17.2 cm. long)

- 1 eighteen-sided die with the numbers “1” through “16” and characters meaning “win” and “lose”.

Like most ancient board games, there isn’t a full set of rules. However, here is a summary of the theorized rules:

“Two people sit facing each other over a board, and the board is divided into twelve paths, with two ends, and an area called the “water” in the middle. Twelve game pieces are used, which according to the ancient rules are six white and six black. There are also two “fish” pieces, which are placed in the water.

Throwing of the dice is done with a jade. The two players take turns to throw the dice and move their pieces. When a piece has been moved to a certain place it is stood up on end, and called an “owl”. Thereupon it can enter the water and eat a fish, which is also called “pulling a fish”.

Every time a player pulls a fish, he gets two tokens. If he pulls two fish in a row, he gets three tokens (for the second fish). If a player has already pulled two fish but does not win, it’s called double-pulling a pair of fish.

When one player wins six tokens the game is won.”

Tafl Games and the Birth of Chess

(400 AD)

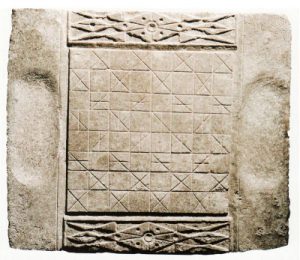

Tafl games are a family of ancient Germanic and Celtic strategy board games played on a checkered board with two armies of uneven numbers.

Although the size of the board and the number of pieces varied, all games involved a distinctive 2:1 ratio of pieces, with the lesser side having a king-piece that started in the centre. The king’s objective was to escape to the board’s periphery or corners, while the greater force’s objective was to capture him. The attacking force has the natural advantage at the start of each game. It’s presumed this indicated the cultural aspect by mimicking the success of Viking raids.

Tafl spread everywhere Vikings traveled, including Iceland, Britain, Ireland, and Lapland. Several iterations of the game, were played across much of Northern Europe.

It’s presumed Tafl branched off into an iteration called Chaturanga. Chaturanga is an ancient Indian strategy game developed in the Gupta Empire, India around the 6th century AD. In the 7th century, it was adopted as shatranj in Sassanid Persia, which in turn was the form of chess brought to late-medieval Europe.

Chaturanga set

Chaturanga was played on an 8×8 uncheckered board, called Ashtāpada. The board sometimes had special markings, the meaning of which is unknown today.

Soon after, the game was turned into its European variant, Chess, which is played on the same 8×8 tile board. The earliest evidence of chess is found in Sassanid Persia around 600 AD. It’s theorized Muslim traders came to European seaports with ornamental chess kings as curios before they brought the game of chess.

The game reached Western Europe and Russia by at least three routes, the earliest being in the 9th century. By the year 1000 it had spread throughout Europe. Introduced into the Iberian Peninsula by the Moors in the 10th century, it was described in a famous 13th-century manuscript covering shatranj, backgammon, and dice named the Libro de los juegos.

Around 1200, the rules of Shatranj (the Persian form of Chess) started to be modified in southern Europe, and around 1475, several major changes made the game essentially as it is known today. These modern rules for the basic moves had been adopted in Italy and Spain. Pawns gained the option of advancing two squares on their first move, while bishops, and queens acquired their modern abilities. The queen replaced the earlier vizier chess piece towards the end of the 10th century and by the 15th century had become the most powerful piece. Consequently, modern chess was referred to as “Queen’s Chess” or “Mad Queen Chess”. These new rules quickly spread throughout western Europe. The rules concerning stalemate were finalized in the early 19th century. The results of these rule changes is what standardized the game of Chess we play today.

During the Age of Enlightenment, chess was viewed as a means of self-improvement. Benjamin Franklin even wrote an article titled “The Morals of Chess” in 1750. He stated:

“The Game of Chess is not merely an idle amusement; several very valuable qualities of the mind, useful in the course of human life, are to be acquired and strengthened by it, so as to become habits ready on all occasions; for life is a kind of Chess, in which we have often points to gain, and competitors or adversaries to contend with, and in which there is a vast variety of good and ill events, that are, in some degree, the effect of prudence, or the want of it. By playing at Chess then, we may learn”

Chess was soon after implemented into schools, where the first chess clubs began. While chess isn’t officially in the Olympics, it’s recognized as a sport by the International Olympic Committee (IOC). It even has its own Olympiad, held every two years as a team event. Most countries have a national chess organization as well.

The First Evidence of Mancala

(700 AD)

Mancala is usually referred to as a specific game, however it’s actually a genre of game. This family of board games is played around the world and referred to as “sowing” games, or “count-and-capture” games, which describes the gameplay. The word mancala comes from the Arabic word naqala meaning “to move”. More than 800 names of traditional mancala games are known, and almost 200 invented games have been described. However, some names denote the same game, while some names are used for more than one game.

Most mancala games share a common general game play. Players begin by placing a certain number of seeds, prescribed for the particular game, in each of the pits on the game board. A player may count their stones to plot the game. A turn consists of removing all seeds from a pit, “sowing” the seeds (placing one in each of the following pits in sequence) and capturing based on the state of board. This leads to the English phrase “count and capture” sometimes used to describe the gameplay.

A Mancala board is typically constructed of various materials, with a series of holes arranged in rows, usually two or four. The materials include clay and other shape-able materials. Some games are more often played with holes dug in the earth, or carved in stone. The holes may be referred to as “depressions”, “pits”, or “houses”. Sometimes, large holes on the ends of the board, called stores, are used for holding the pieces.

Playing pieces are seeds, beans, stones, cowry shells, half-marbles or other small undifferentiated counters that are placed in and transferred about the holes during play.

The objective of most two and three-row mancala games is to capture more stones than the opponent. In four-row games, one usually seeks to leave the opponent with no legal move or sometimes to capture all counters in their front row.

At the beginning of a player’s turn, they select a hole with seeds that will be sown around the board. This selection is often limited to holes on the current player’s side of the board, as well as holes with a certain minimum number of seeds.

In a process known as sowing, all the seeds from a hole are dropped one-by-one into subsequent holes in a motion wrapping around the board. Sowing is an apt name for this activity, since not only are many games traditionally played with seeds. Placing seeds one at a time in different holes reflects the physical act of sowing. If the sowing action stops after dropping the last seed, the game is considered a single lap game.

The earliest evidence of the game are fragments of a pottery board and several rock cuts found in Aksumite areas in Matara (in Eritrea) and Yeha (in Ethiopia). They’re dated by archaeologists to between the 6th and 7th century AD. The game may have been mentioned by Giyorgis of Segla in his 14th century Ge’ez text Mysteries of Heaven and Earth, where he refers to a game called qarqis, a term used in Ge’ez to refer to both Gebet’a (mancala) and Sant’araz (modern sent’erazh, Ethiopian chess).

Pit marks presumed to be ancient mancala boards

The similarity of some aspects of the game to agricultural activity and the absence of a need for specialized equipment present the intriguing possibility that it could date to the beginnings of civilization itself; however, there is little verifiable evidence the game is older than about 1300 years.

The Landlord’s Game

(1903)

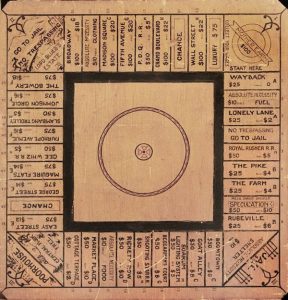

What? You’ve never heard of The Landlord’s Game? It was invented by Lizzie Magie, one of America’s very first board game designers. The game board consisted of a square track, with a row of properties around the outside that players could buy. The game board had four railroads, two utilities, a jail, and a corner named “Labor Upon Mother Earth Produces Wages,” which earned players $100 each time they passed it… Sound familiar?

Magie had invented and patented The Landlord’s Game in 1904 and designed the game to be a practical demonstration of land grabbing with all its usual outcomes and consequences. She based the game on the economic principles of Georgism, a system proposed by Henry George, with the object of demonstrating how rents enrich property owners and impoverish tenants.

She knew some people could find it hard to understand why this happened and what might be done about it, and thought if Georgist ideas were put into the concrete form of a game, they might be easier to demonstrate. Magie also hoped that when played by children the game would provoke their natural suspicion of unfairness, and that they might carry this awareness into adulthood.

In 1935 Magie sold her patent for The Landlords Game to Parker Brothers, which is now what we know as Monopoly. This game, which launched Parker Brothers into a massive success, was originally rejected by them.

After their success with Monopoly, They went on to produce Risk, Sorry, Trivial Pursuit, and more.

Lizzie Magie sold her original patent of the original game for $500.

The Oscars of Board Games

(1978)

The Spiel des Jahres is a German title that simply translates to “Game of the Year”. It’s considered the most prestigious award for board and card games and is awarded annually by a jury of German game critics.

The Spiel des Jahres has the stated purpose of rewarding excellence in game design, and promoting top-quality games in the German market. It is thought the existence and popularity of the award is one of the major drivers of the quality of games coming out of Germany.

A Spiel des Jahres nomination can increase the typical sales of a game from 500-3,000 copies to around 10,000; and the winner can usually expect to sell 300,000 to 500,000 copies.

The criteria on which games are evaluated are:

Game concept: originality, playability, game value

Rule structure: composition, clearness, comprehensibility

Layout: box, board, rules

Design: functionality, workmanship

List of Spiel des Jahres winners (Click for larger image)

The Spield Des Jahres has been responsible for the popularity and growth of games like Settlers of Catan, Dominion, Hanabi, and Dixit. It’s also considered one of the main drivers for the popularity of the Euro Games genre.

Euro Games are a class of tabletop game that generally downplay luck, have indirect player interaction, and focus on economics and strategy.

Catan’s Influence in The States

(1995)

The Settlers of Catan was one of the first Eurogames to achieve popularity outside of Europe. Over 24 million games in the Catan series have been sold and the game has been translated in over 30 languages.

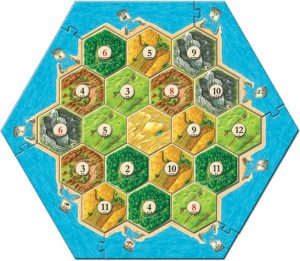

In Catan, players compete to establish the most successful colony on a fictional island called Catan (clever, eh?). The game board, representing the island, is composed of hexagonal tiles of different land types.

On each player’s turn, they roll dice (amongst other means) to see if the land they occupy produces resources, which they use to build roads, cities, and settlements.

By building settlements and gaining cards, players earn points leading to victory. Unlike most board games, Catan entices players to go outside the confines of strict rules – allowing them to come to their own agreements when trading resources and money with one another.

Catan’s popularity in the United States has gotten it dubbed “The board game of our time” by The Washington Post. It’s also featured in the 2012 American documentary film titled Going Cardboard, which details the game’s impact on American gaming communities.

The game was created by Klaus Teuber who was working as a dental technician outside the industrial city of Darmstadt, Germany in the 80s. Teuber was designing elaborate board games in his basement on his free time. He stated that he used this as an escape from work.

Now 62, Teuber is still somewhat baffled by the popularity of his creation. He never expected it would be so successful.

Almost all board-game designers, even the most successful ones, work full time in other professions; Teuber is one of a tiny handful who make a living from games.

When he appears at major gaming conventions, Teuber is greeted like a rock star.

For a lot of gamers, myself included, Catan was a gateway into the world of Eurogames. Before Catan, talking about board games usually meant you were referring to titles like Sorry, Monopoly, Trivial Pursuit, and Battleship – games that never excited anyone.

Settlers of Catan was a primary catalysts for the sudden popularity of board games in the United States. It made people hunger for more games that, at the time, had a very different set of rules and mechanics.

Kickstarter Gives People the Ability to Fund New Games

(2009)

With the disruption to the table top market from games like Carcassonne, Catan, Alhambra, and Ticket to Ride, people were eager for more. However, creating and getting a board game to market is no easy task.

Most game designers have full time jobs and creating games is merely their hobby (yes, even for popular games!). They typically only make enough profit to break even or at best squeeze out a couple expansions.

… That is, until Kickstarter.

In case you’ve been living under a rock, laying on a deserted island, which resides in a hidden cave on another planet, Kickstarter is a global crowdfunding platform that helps bring creative projects to life.

Originally intended for music and film, it has backed over 200,000 projects such as music, shows, comics, digital products, and of course, board games. Kickstarter has raised more than $1.5 billion towards their projects and backers are offered tangible rewards in exchange for their pledge.

Kickstarter has been revolutionary to the board game market, as it gives avid gamers a chance to put their idea out in front of other like minded people. It gave the table top community a way to bring silent ideas to life. You wouldn’t believe how much some of these games have actually raised.

The Conan Board game Kickstarter campaign launched on January 12th 2015 with a hefty goal of $80,000. It received full funding within 5 minutes and 37 seconds. Not only that, it went on to raise a total of $3,327,757.

And it’s not just board games. Dwarven forge raised a total of $2,140,851 and only makes physical terrain tile pieces for role playing games.

As I’m writing this, there are currently 213 table top related projects you can fund on Kickstarter. That’s a great display of how far the board game community has come.

Board Gaming Becomes a Yearly World Wide Event

(2013)

We finally circle back around to one of the biggest catalysts for the recent explosion in board gaming popularity, TableTop. TableTop is a web series about board games and was created by Wil Wheaton and Felicia Day. In each episode Wil Wheaton plays board games with popular TV and web personalities.

TableTop started out as a show on the Geek & Sundry Youtube Channel and quickly became its most popular series. The original concept for Tabletop was that Wil Wheaton (who’s an avid board gamer) would review board games. However, Wil Wheaton proposed that the best way to show how great games are, is to play them. And, based off their success, they nailed it.

Tabletop had grown to such a point that by the third season, they put up a crowd funding campaign in an effort to become independent. Their target was $500,000 and they raised nearly triple that. They recently announced they would use the extra proceeds to launch a similar web series titled “Titan’s Grave: The Ashes of Valcana”.

Titan’s Grave will be a multi-episode show focused on a single role playing board game. Geek & Sundry has teamed up with Green Ronin Publishing (creators of several RPG titles, including Dragon Age) to create a new game engine that they will be using to power their RPG game.

TableTop has become a resonating force in the gaming community. They focus on introducing gaming to new people that still have a misguided view of board gaming. A lot of people still think of Monopoly and Risk when they think of board games. TableTop’s popularity has started to shift this. The show has gotten so popular that board games featured on the show see skyrocketing sales. When Tsuro was featured on the show, demand was so high, the publisher exhausted all stock reserves. For a time, the game was unavailable in Europe, as production tried to cope with US demand. Game manufacturers have dubbed this “The Wheaton Effect”.

So what does a popular Youtube channel have to do with a yearly worldwide event? In 2013 Wil and Felicia held International Tabletop Day, where they played several games live with folks from previous episodes. The next year, the event had spiraled into a world wide celebration with events in over 80 countries. The next Tabletop Day will be held on April 11th 2015 and game stores from all over the world are announcing various events and promotions for their participation. Board gaming has officially become a world wide holiday.

What’s in Store for the Future?

Everyone’s built a friendly community both online and off where people share reviews, strategies, thoughts, and even painting techniques for board gaming. Though the community continues to grow at a radical pace, it’s still in its infancy. Keep holding your board game nights and events to introduce new people to the fun of tabletop. There’s still so much more to come!