By denying official commemoration, civic ritual, and institutional validation, the state ensured that loss did not acquire retrospective dignity.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Memory, Defeat, and the Problem of Romanticization

The Jacobite Rebellions posed a persistent and serious challenge to the British state between the late seventeenth and mid-eighteenth centuries, culminating in a final and decisive defeat at Culloden in 1746. These uprisings were not marginal disturbances, cultural protests, or symbolic gestures of dissent. They were repeated, organized attempts to overturn the post-Glorious Revolution settlement and restore the Stuart dynasty through military force, foreign alliance, and domestic mobilization. For decades, Jacobitism represented a viable alternative claim to sovereignty, one capable of drawing aristocratic support, international backing, and armed followers. Its suppression resolved a constitutional struggle that had spanned generations, yet it also created a problem that extended beyond the battlefield. Defeat settled the question of power, but it left unresolved how that defeat would be remembered, narrated, and incorporated into Britain’s historical consciousness without reopening the legitimacy it had sought to extinguish.

Political memory is never neutral, and in the aftermath of rebellion it becomes especially volatile. The British state confronted the danger that failed insurgency might be reinterpreted as noble resistance, transforming military loss into moral capital. Such a reframing would have destabilized the authority secured through victory by allowing sympathy to substitute for legitimacy and cultural identification to blur constitutional judgment. The central issue was not whether Jacobitism would be remembered, since forgetting was neither feasible nor desirable, but how that remembrance would be structured and constrained. The state needed to ensure that memory did not slide into endorsement, that defeat did not acquire retrospective dignity, and that loss did not become a foundation for renewed moral claim. The distinction between memory and honor became a problem of governance rather than sentiment, demanding careful and sustained discipline.

Jacobitism did acquire a rich afterlife in song, poetry, and romantic literature. This cultural memory emphasized loyalty, sacrifice, and loss, particularly within Highland and diasporic traditions. Yet this process unfolded largely outside the institutions of the state. While folklore and private nostalgia were tolerated, they were never translated into official commemoration or civic recognition. There were no national monuments to Jacobite leaders, no state-sanctioned anniversaries of defeat, and no honored burial sites validated by public authority. The boundary between cultural remembrance and political legitimacy was carefully maintained.

The British response to Jacobite memory demonstrates a deliberate refusal to romanticize defeat through civic honor. The state allowed cultural memory to persist precisely because it posed no institutional threat, while consistently denying Jacobitism any form of official validation. By distinguishing between nostalgia and legitimacy, Britain preserved the finality of Jacobite defeat while permitting its transformation into a harmless cultural past. The Jacobite Rebellions reveal how enduring states manage the memory of failed challenges by allowing remembrance without reward and history without rehabilitation.

Jacobitism as Political Challenge, Not Cultural Identity

Jacobitism emerged in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries as a coherent political project centered on dynastic restoration, not as an expression of cultural grievance or romantic identity. Its adherents sought the return of the Stuart line to the British throne and the reversal of the constitutional settlement established after 1688. This objective placed Jacobitism squarely within the realm of state power, succession, and legitimacy. Contemporary supporters understood their cause as a concrete alternative government, one that could command allegiance, raise armies, and negotiate alliances with foreign powers.

The movement’s political character is evident in its organizational structure and strategic aims. Jacobite leaders cultivated extensive networks among nobles, clergy, military officers, and exiled courtiers, while maintaining active correspondence with foreign courts, particularly in France and Spain. Rebellions were planned with careful attention to timing, logistics, supply routes, and regional coordination rather than symbolic display or ritual protest. Proclamations issued during uprisings articulated claims of lawful sovereignty, invoking hereditary right and divine sanction, and framed resistance as obedience to a rightful monarch rather than insurrection against the state. These actions reflected a calculated pursuit of power grounded in established political norms, not an assertion of cultural identity detached from governance.

Jacobitism did not initially present itself as a vehicle for regional, ethnic, or folkloric expression. Later romantic associations with Highland culture obscure the movement’s original breadth and intent. Highland participation, though militarily significant, was understood by contemporaries as one element within a larger and more diverse coalition. English Jacobites, Irish supporters, and Scottish Lowland elites all played substantial roles in planning, financing, and executing the rebellions. Religious allegiance, dynastic loyalty, and opposition to the post-1688 settlement motivated supporters far more than shared cultural symbolism. The cause was constitutional and dynastic in scope, appealing to those who viewed the existing regime as illegitimate rather than to a community united by myth or identity.

The British state recognized Jacobitism as a legitimate threat precisely because it operated within familiar political frameworks. Rebellions were treated as acts of treason, not as expressions of cultural protest or regional dissent. Legal responses emphasized the preservation of state authority through prosecution, forfeiture of estates, transportation, and the dismantling of organizational capacity. This response underscored the prevailing understanding that Jacobitism contested sovereignty itself, seeking to replace the existing regime rather than merely criticize it from the margins.

Only after repeated failure did Jacobitism begin to shed its political immediacy. As military defeat accumulated, leadership fragmented, and foreign support diminished, the movement gradually lost its capacity to function as a credible alternative government. This erosion was not sudden nor uniform, but the cumulative effect of strategic failure and structural suppression. The transition from political challenge to cultural memory emerged slowly, shaped by the disappearance of practical possibility rather than by any intentional redefinition of purpose. Jacobitism became nostalgic only once it could no longer plausibly govern.

Recognizing Jacobitism as a political challenge rather than a cultural identity is essential for understanding how it was remembered. The British state’s later tolerance of Jacobite folklore did not represent retrospective acceptance of its aims, but recognition that the movement no longer possessed the capacity to threaten legitimacy. Memory softened only after authority was secure. Jacobitism could be permitted to survive as song and story precisely because it had first been decisively defeated as a political alternative.

Defeat and Finality after 1746

The defeat of Jacobite forces at Culloden in April 1746 marked a decisive break between rebellion as political possibility and Jacobitism as historical residue. Unlike earlier risings, which had ended ambiguously or left open the prospect of renewed challenge, Culloden functioned as a terminal event. The battle destroyed the military capacity of the Jacobite cause and demonstrated the British state’s ability to impose order decisively. In this sense, Culloden did not merely end a campaign; it closed a constitutional question that had lingered since the Revolution of 1688.

What distinguished Culloden from prior defeats was the speed and comprehensiveness with which finality followed. The battlefield loss was immediately reinforced by systematic suppression. Jacobite command structures collapsed, leading figures fled or were captured, and the movement’s remaining networks were exposed and dismantled. The Stuart claim, already weakened by distance and dependence on foreign support, ceased to function as a credible alternative to the Hanoverian regime. Defeat translated swiftly into political extinction rather than into a prolonged aftermath of uncertainty.

State policy after 1746 further ensured that Jacobitism would not survive as an organized force. Legal measures targeted not only those who had borne arms but also the broader social and institutional structures that had sustained rebellion. Confiscations deprived Jacobite elites of land and influence, prosecutions removed leadership from public life, and transportation dispersed supporters beyond the reach of coordinated action. Legislative reforms aimed at dismantling traditional power bases in the Highlands sought to prevent the reconstitution of armed resistance altogether. These measures were framed not as punitive excess but as necessary instruments of closure, designed to ensure that Jacobitism would not reappear under altered circumstances.

Equally important was the symbolic dimension of this settlement. The British state did not attempt to negotiate reconciliation between competing dynastic claims or to absorb Jacobitism as a dissenting tradition within the constitutional order. Instead, it treated defeat as final and non-negotiable, insisting on the moral and political asymmetry between victor and vanquished. The Stuart cause was not preserved as a lost alternative future for the nation, nor was it framed as a morally instructive failure worthy of sympathetic remembrance. Culloden became a boundary in historical narrative as well as in political practice, marking the moment at which Jacobitism ceased to be a legitimate contender for power and was fixed as a resolved error of the past. By refusing to dignify defeat with reconciliation or honor, the state ensured that closure was not merely administrative but interpretive.

The consequences of this finality decisively shaped how Jacobitism would later be remembered. Because the movement had been defeated comprehensively and stripped of any residual claim to legitimacy, its eventual transformation into cultural nostalgia posed little threat to the state. Songs, stories, and romantic representations could emerge only after the possibility of restoration had been extinguished beyond recovery. Memory followed defeat rather than competing with authority. Culloden established the conditions under which Jacobitism could survive in cultural form while remaining absent from civic life, ensuring that remembrance reinforced settlement rather than undermined it.

The British State and the Refusal of Official Commemoration

Following the final defeat of Jacobitism, the British state adopted a consistent and deliberate policy of refusing official commemoration of the rebellion and its leaders. This refusal was not a temporary reaction to recent violence but a sustained position maintained even as the immediate threat receded. While other defeated causes in British history were eventually folded into narratives of national development or reconciled through symbolic gestures, Jacobitism remained excluded from civic recognition. The state made no effort to memorialize Jacobite sacrifice or loss, signaling that defeat had extinguished not only political viability but also the claim to public honor.

This absence was most visible in the landscape of national memory and remained conspicuous precisely because it was so complete. There were no state-sponsored monuments to Jacobite leaders, no official burial sites accorded honor by the crown, and no public rituals marking the anniversaries of defeat. Culloden itself was not transformed into a site of national mourning, pilgrimage, or tragic reflection sanctioned by the state. The silence was intentional rather than neglectful. Official commemoration would have implied that the Jacobite cause represented a legitimate, if unsuccessful, alternative path for the nation’s political development. By withholding such recognition, the British government preserved a clear narrative hierarchy in which constitutional authority and dynastic settlement stood above failed rebellion, leaving no ambiguity about where legitimacy resided.

The refusal of commemoration extended beyond monuments to the realm of ceremony and calendar. National observances, royal anniversaries, and public rituals emphasized Hanoverian legitimacy, Protestant succession, and political continuity. Jacobite events were absent from the civic calendar, denied the repetitive reinforcement that ritual provides. This omission mattered. Without periodic public recognition, memory remained fragmented, confined to private spaces rather than institutionalized through state practice. The rebellion was remembered as history, not reenacted as tradition.

This policy did not require the suppression of cultural expression and in fact depended upon its separation from civic authority. Songs, poems, and stories celebrating Jacobite loyalty circulated widely, particularly in Scotland and among diasporic communities, where they functioned as expressions of identity, loss, and nostalgia. The state did not attempt to eradicate these forms of memory, recognizing that folklore, literature, and oral tradition lacked the institutional power to confer legitimacy. What it consistently denied was the translation of cultural remembrance into civic honor. No song became a state anthem, no ballad entered official ceremony, and no literary rehabilitation was accompanied by public recognition. The boundary between tolerated nostalgia and authorized memory remained firm, ensuring that emotional attachment did not evolve into political endorsement.

By refusing official commemoration, the British state demonstrated an acute understanding of how memory operates within political systems. Civic honor functions as validation, not mere recollection. To commemorate is to authorize, to signal that loss may still carry dignity within the national story. The denial of such honor to Jacobitism reinforced the finality of defeat and preserved the legitimacy secured by victory. Memory was allowed to persist, but legitimacy was not shared. In this distinction lay the durability of the post-1746 settlement.

Romantic Jacobitism and the Rise of Cultural Memory

By the early nineteenth century, Jacobitism had undergone a profound transformation from defeated political movement to romantic cultural memory. This shift did not occur immediately after 1746, nor was it an inevitable response to defeat. For decades, Jacobitism lingered in a state of political disqualification rather than sentimental rehabilitation. Only after the practical possibility of Stuart restoration had fully disappeared did space open for reinterpretation. Once Jacobitism no longer posed a constitutional threat, it could be reimagined as a subject of nostalgia, sentiment, and aesthetic fascination rather than political danger. Cultural memory emerged not as a continuation of political struggle but as its replacement, filling the vacuum left by irrevocable failure.

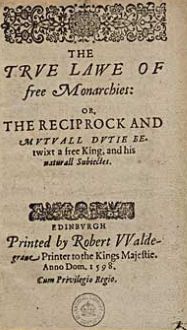

Literature played a decisive role in this transformation. Writers and poets recast Jacobite defeat as a story of loyalty, loss, and vanished worlds, abstracted from its original political aims. The work of Walter Scott was especially influential in shaping this romantic vision. Scott’s portrayals emphasized chivalry, honor, and personal devotion while minimizing the constitutional stakes of rebellion. Jacobitism became a backdrop for melancholy reflection rather than a program for governance, its historical sharpness softened into literary pathos.

Music and oral tradition reinforced this process. Jacobite songs circulated widely, preserving themes of exile, fidelity, and sorrow rather than calls to renewed action. These ballads rarely articulated concrete political demands. Instead, they framed defeat as emotionally resonant but politically closed. The persistence of song allowed memory to survive without threatening authority, since it operated within the realm of feeling rather than institution. Cultural transmission ensured continuity of remembrance while simultaneously confirming its harmlessness.

Material culture also contributed significantly to the romanticization of Jacobitism. Tartan, Highland dress, and symbolic artifacts associated with the rebellions were detached from their original political context and reintroduced as markers of heritage and aesthetic identity. What had once been treated as suspect or subversive became objects of curiosity, nostalgia, and consumption. This transformation depended on the prior destruction of their political function. Symbols could be revived only after they no longer signified allegiance to a rival sovereign. Their reinvention signaled not resistance but reconciliation with defeat, allowing identity to persist without authority.

Romantic Jacobitism was not a state-sponsored project, nor did it require official encouragement to flourish. Its growth occurred through private publication, regional tradition, and commercial culture rather than through public institutions or civic ritual. The British state neither promoted nor formally endorsed this reinterpretation of the past. Tolerance did not imply approval. By allowing romantic memory to circulate outside official channels, the state preserved a clear and deliberate distinction between cultural expression and civic authority. Jacobitism could be mourned, imagined, and aestheticized, but it could not be legitimated or publicly honored.

The rise of romantic Jacobitism illustrates how cultural memory can flourish in the absence of political consequence. Nostalgia replaced ambition, and sentiment substituted for sovereignty. This transformation did not rehabilitate the Jacobite cause; it neutralized it. By the time Jacobitism entered the cultural imagination as a noble lost cause, it had already been conclusively defeated as a political one. Romantic memory survived precisely because civic honor remained withheld.

Cultural Nostalgia versus Civic Legitimacy

The emergence of romantic Jacobitism clarified a boundary that the British state had drawn deliberately and maintained consistently: cultural memory was permissible, but civic legitimacy was not transferable. Nostalgia could flourish precisely because it lacked institutional force. Songs, novels, and symbols allowed individuals and communities to process loss without challenging the constitutional order that had rendered that loss final. In this distinction lay the durability of the post-Jacobite settlement. Memory became a private and cultural phenomenon, while legitimacy remained the exclusive domain of the state.

Civic legitimacy differs fundamentally from cultural remembrance because it carries institutional endorsement and public consequence. To honor publicly is not merely to remember but to validate, to signal that a cause or actor deserves incorporation into the authoritative national story. The British state consistently refused to grant Jacobitism this status. No matter how sympathetically the cause was portrayed in literature or folklore, it never crossed into official recognition. There were no state rituals that elevated Jacobite sacrifice, no monuments that framed defeat as noble service, and no civic spaces that invited public identification with the lost cause. This refusal was not accidental or passive. It reflected an understanding that public honor confers moral weight and that such weight, once granted, is difficult to retract. By withholding civic legitimacy, the state ensured that sympathy never hardened into endorsement.

This separation allowed cultural nostalgia to exist without political consequence by channeling attachment into non-institutional forms. Romantic memory functioned as a mechanism of containment, redirecting loyalty and sentiment away from the structures of power and into aesthetic and emotional registers. Jacobitism could be remembered as poignant, even admirable in its expressions of personal loyalty or suffering, without being treated as legitimate in political terms. Crucially, the state did not attempt to suppress these cultural expressions, recognizing that suppression would risk granting them oppositional energy. Instead, it allowed nostalgia to circulate precisely because it remained detached from authority. Memory softened defeat without redeeming it, preserving the finality of loss while permitting its emotional afterlife.

The Jacobite case illustrates a broader principle of political memory. States that endure do not suppress all remembrance of defeated challenges, nor do they permit remembrance to evolve into validation. By maintaining a strict boundary between cultural nostalgia and civic legitimacy, the British state allowed memory to soften without surrendering authority. Jacobitism survived in story and song, but it did not reenter the civic realm as an honored tradition. In this restraint lay the clarity and stability of the post-1746 order.

Conclusion: When Memory Is Allowed but Honor Is Withheld

The Jacobite Rebellions reveal how a state can defeat a political challenge without attempting to erase it from memory. Britain did not impose silence on Jacobitism, nor did it require collective forgetting of the uprisings that had once posed a serious threat to its constitutional order. Instead, it permitted remembrance to persist while carefully disciplining the meanings that remembrance could assume. Defeat closed the question of legitimacy decisively, but memory remained available as history, culture, and private reflection rather than as a claim upon public authority. By allowing the past to be known without allowing it to be redeemed, the British state integrated Jacobitism into historical consciousness without reopening the political struggle it had resolved.

The British refusal to honor Jacobitism publicly was not an act of repression but of restraint. By denying official commemoration, civic ritual, and institutional validation, the state ensured that loss did not acquire retrospective dignity. Jacobitism could be studied, narrated, and even mourned, but it could not be incorporated into the national story as an honorable alternative. This distinction prevented sympathy from becoming a substitute for authority and ensured that defeat remained final rather than morally reversible.

The coexistence of cultural nostalgia and civic silence was not a contradiction but a deliberate strategy of containment. Allowing folklore, literature, and song to flourish redirected attachment away from political structures and into emotional and aesthetic registers. Romantic memory softened the human experience of defeat without rehabilitating the cause itself or reviving its claims to legitimacy. By tolerating cultural expression while refusing public honor, the state ensured that memory functioned as reflection rather than mobilization. Jacobitism was permitted to survive as sentiment precisely because it had been stripped of any capacity to reenter civic life as a legitimized tradition.

The Jacobite case offers a clear lesson in the management of political memory. States that endure distinguish between remembering and honoring, between cultural expression and civic validation. When memory is allowed but honor is withheld, defeat can be absorbed into history without destabilizing authority. Jacobitism survived as nostalgia because it was denied legitimacy, demonstrating that the most durable settlements are those that permit remembrance while refusing redemption.

Bibliography

- Assmann, Jan. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Black, Jeremy. Culloden and the ’45. London: St. Martin’s Press, 1990.

- Colley, Linda. Britons: Forging the Nation 1707–1837. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

- Devine, T. M. The Scottish Nation: A History 1700–2000. London: Penguin, 1999.

- Harris, Bob. “England’s Provincial Newspapers and the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745–1746.” History 80:258 (1995), 5-21.

- Hobsbawm, Eric. Nations and Nationalism since 1780. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Malithong, Rachatapong. “Jacobites’ Anti-Unionism in the Eighteenth Century: A Threat to the Union between England and Scotland.” ARTS: Journal of Arts and Thai Studies 45:2 (2023), 1-18.

- Marshall, Peter. Beliefs and the Dead in Reformation England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Martin, Nicola. “Inculcating Loyalty in the Highlands and Beyond, c.1745-1784.” Atlantic Studies 21:2 (2024), 265-286.

- Perkins, Pam. “The “candour, which can feel for a foe”: Romanticizing the Jacobites in the Mid-Eighteenth Century.” Lumen 31 (2012), 131-143.

- Pittock, Murray. Jacobitism. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 1998.

- —-. The Myth of the Jacobite Clans. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1995.

- Sankey, Margaret. “Good Manners and Bad Treasons: Scottish Jacobite Women and the British Authorities in the Rebellion of 1715.” Journal x: A Journal in Culture and Criticism 7:1,6 (2002).

- Scott, Walter. Waverley; or, ’Tis Sixty Years Since. Edinburgh: Archibald Constable, 1814.

- Szechi, Daniel. The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688–1788. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994.

- —-. “The Long Shadow of 1715. The Great Jacobite Rebellion in Jacobite Politics and Memory — a Preliminary Analysis.” Royal Stuart Journal 7 (2016), 20-47.

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh. “The Invention of Tradition: The Highland Tradition of Scotland.” In The Invention of Tradition, edited by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, 15–41. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Young, James E. The Texture of Memory. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.11.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.