Pharaohs, emperors, kings, and dynasts ruled not only by force but by embedding their power in cosmic, divine, or ancestral frameworks.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

To speak of liberty in the ancient world is to confront a silence more profound than any articulated opposition. Societies stretching from the Nile Valley to the Yellow River ordered their political and social lives around figures of authority whose legitimacy was rarely contested in terms recognizable to later ages. The notion of “individual freedom” as a political value was alien. What people sought was not autonomy but order, continuity, and the assurance that the cosmic and social spheres remained in harmony. In this context, absolute rule was not merely tolerated. It was sanctified.

Kingship and Cosmic Balance in Egypt

The Egyptians, whose civilization endured for millennia, epitomized the fusion of kingship and cosmic order. Pharaoh was not only a political leader but the living Horus, embodiment of divine kingship on earth. His authority derived from ma’at, the principle of truth, justice, and balance that underpinned the universe.1 To obey Pharaoh was not submission to an arbitrary ruler but participation in the maintenance of cosmic balance.

The monumental scale of Egyptian architecture underscored this political theology. Pyramids, temples, and colossal statues communicated permanence, stability, and power. They reinforced the idea that authority was eternal, that Pharaoh’s command was inseparable from the rising of the sun and the flooding of the Nile.2 Political legitimacy was thus carved in stone and aligned with the natural cycles that sustained life.

Pharaonic authority extended into the afterlife. Funerary texts and tomb inscriptions envisioned Pharaoh’s continued reign beyond death, traveling with the sun god through the underworld and ensuring the renewal of cosmic order. Kingship was never temporary or fragile. It was eternal, with human succession only a reflection of divine continuity. The Egyptian imagination therefore made resistance not only politically futile but cosmologically absurd.

Mesopotamian Mandates and the Burden of Justice

In Mesopotamia, kingship rested on divine mandate, with rulers portrayed as shepherds responsible for their people’s well-being. Hammurabi’s famous code, engraved beneath the image of the king receiving authority from Shamash, the sun god of justice, demonstrates the intimate linkage between divine sanction and human law.3 The king’s word was binding not because it emanated from his person alone but because it carried the imprimatur of the gods.

Yet this legitimacy carried weighty obligations. If justice faltered or crops failed, it was interpreted as divine disfavor, sometimes justifying dynastic overthrow. Kingship could be lost, dynasties replaced, but the principle of centralized authority never disappeared.4 To imagine a world without a king was to imagine a cosmos without order.

Greece and the Uneasy Question of Rule

The Greek world complicates the picture but does not overturn it. Early Greek kings and tyrants embodied the same expectation of absolute power familiar across the ancient Near East. In Homeric epics, kings command armies and dispense justice without reference to popular consent. Odysseus’ authority, even when challenged, rested not on negotiation with equals but on charisma and divine favor.5

By the archaic period, Greek poleis had developed traditions of collective decision-making. Tyrannies arose as well, often justified by promises of restoring balance after oligarchic corruption. The tyrant’s authority, though sometimes resented, was still conceived as legitimate in its absoluteness, rooted in strength and divine approval.

Classical Athens, often celebrated for its democracy, provides an instructive exception. Yet even here, freedom (eleutheria) referred less to individual autonomy than to the collective privilege of the polis to govern itself. Women, slaves, and foreigners remained excluded. The freedom of the Athenian male citizen was not the negation of rule but a share in it.6

Outside Athens, most Greek states retained oligarchic or monarchical structures, suggesting that the democratic experiment was notable precisely for its rarity. What Athens offered was not liberty in the modern sense but an unusual form of political participation, framed by the suspicion that unchecked individuality threatened the stability of the community.

Rome and the Cult of Authority

The Roman Republic, like Athens, articulated concepts of liberty (libertas) that seem to anticipate later ideals. Yet Roman liberty was defined within the obligations of citizenship and service to the res publica. It did not imply release from the authority of magistrates or the Senate. Authority remained a collective good rather than a personal right.

When Augustus emerged as princeps after the civil wars, the Roman world accepted his authority as the necessary price for stability. Absolute rule, cloaked in republican forms, was sanctified as pax Romana.7 Augustus’ careful balancing act, presenting himself as first among equals while wielding near-total control, set a template for imperial legitimacy.

The imperial cult reinforced this acceptance. Emperors were worshiped as divine or semi-divine figures, their legitimacy tied to both military success and cosmic favor. Even when tyrants like Caligula or Nero fell, the institution of the principate remained unquestioned. Authority itself was sacrosanct, even if individual rulers were not. Rome, like Egypt before it, proved that political legitimacy lay less in personal morality than in the enduring necessity of centralized power.

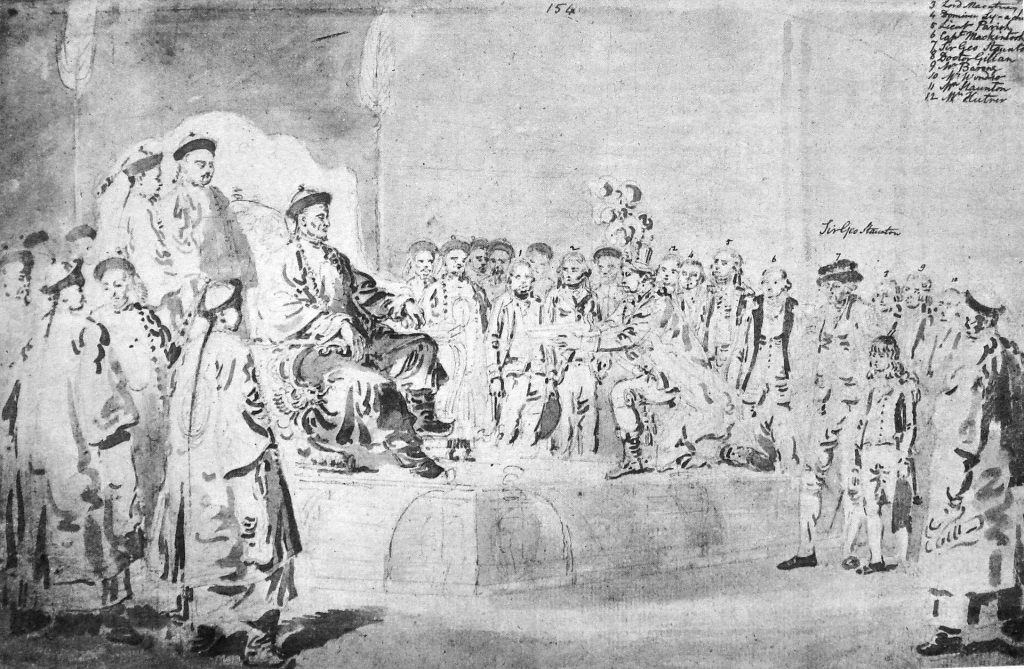

China and the Mandate of Heaven

In China, the idea of absolute rule was refined into a sophisticated doctrine through the Mandate of Heaven. Dynasties ruled by divine sanction, their legitimacy demonstrated through prosperity and stability. Natural disasters or popular unrest were interpreted as signs that the mandate had been withdrawn.8 This principle did not undermine absolute authority but reinforced it. For as long as a dynasty held the mandate, its rule was beyond dispute.

Confucian philosophy further embedded obedience within the moral fabric of society. Hierarchy was not merely political but familial, with the emperor as father of the realm. To resist the ruler was to disrupt the natural order of filial piety and cosmic harmony. Freedom, in this framework, was meaningless outside the network of duties owed to ruler, family, and ancestors. Dynastic succession, whether violent or peaceful, did not question the necessity of kingship itself. Authority was permanent, even when rulers were not.

The Absence of the Individual

Across these civilizations, the common thread is the absence of the individual as a political category. Identity was relational, embedded in kinship, community, and cosmic order. Authority was understood as the glue that held the universe together. Exceptions like Athens or the Roman Republic never centered on personal freedom in the modern sense. They offered participation in governance, but always circumscribed by obligations and exclusions.

The absence of individuality in political thought also shaped law, literature, and memory. Ancient codes were written not to protect personal autonomy but to regulate communal order and delineate hierarchy. Epic traditions celebrated heroes, but even their deeds served collective ends: the restoration of justice, the defense of the polis, the preservation of dynastic continuity. The self appeared in these texts not as a bearer of rights but as an instrument of duty, measured by service to gods, kings, and communities rather than by independence.

Conclusion

The ancient world’s devotion to absolute authority was not merely pragmatic but profoundly metaphysical. Pharaohs, emperors, kings, and dynasts ruled not only by force but by embedding their power in cosmic, divine, or ancestral frameworks. The idea of individual freedom as an inherent good was absent, for human life was understood in collective, hierarchical, and cosmological terms.

To look backward is to see that the question of liberty scarcely arose. What mattered was not the independence of the individual but the endurance of order. Authority, sanctified and centralized, was the answer to the perennial question of survival. In this lies the historical weight of absolute rule: it was not a deviation from freedom but the very ground of political life in the ancient world.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Jan Assmann, The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002), 44–49.

- Toby Wilkinson, The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt (New York: Random House, 2010), 63–68.

- A. Leo Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964), 154–157.

- Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003), 88–92.

- Homer, The Odyssey, trans. Robert Fagles (New York: Penguin, 1996), Book 2.

- Paul Cartledge, Democracy: A Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 45–52.

- Mary Beard, SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome (New York: Liveright, 2015), 312–318.

- Mark Edward Lewis, The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2007), 23–29.

Bibliography

- Assmann, Jan. The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Beard, Mary. SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. New York: Liveright, 2015.

- Cartledge, Paul. Democracy: A Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Homer. The Odyssey. Translated by Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin, 1996.

- Lewis, Mark Edward. The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2007.

- Oppenheim, A. Leo. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC. Oxford: Blackwell, 2003.

- Wilkinson, Toby. The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. New York: Random House, 2010.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.28.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.