In Rome, words were never merely words. They were instruments of power, sharpened in the crucible of political competition and carried into every corner of civic life.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

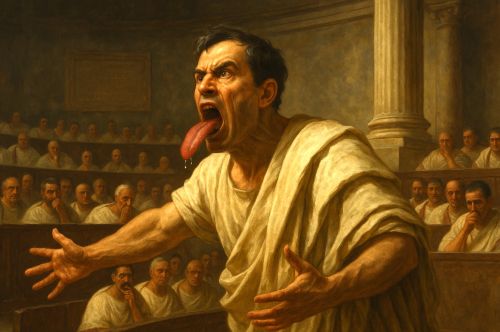

In the Roman world, politics was never simply about policy or persuasion; it was about power, and the tongue itself became a weapon sharpened for combat. To speak in the Forum was to fight in a theater where reputations could be destroyed as easily as lives on the battlefield. Roman orators believed that words could kill, if not directly, then by preparing the ground for violence, exclusion, and even death. Cicero, Sallust, and Tacitus each testify to a culture in which violent rhetoric was not rhetorical flourish alone but a form of political action that carried consequences far beyond the rostra.

The Roman Republic and Empire both reveal how words were used to vilify opponents, to stir crowds into frenzied mobs, and to justify extraordinary measures against political rivals. From Cicero’s blistering Philippics against Mark Antony to the Senate’s vilification of Tiberius Gracchus as a tyrant, verbal violence primed the soil for bloodshed. Rhetoric was not merely descriptive; it was performative, shaping reality by framing enemies as traitors, tyrants, or monsters who could be eliminated without remorse. As one scholar has observed, “the invective was not ancillary to Roman politics, it was its bloodstream.”1

What follows is an exploration of the use and consequences of violent rhetoric in ancient Rome, tracing its presence from the Republic to the Imperial era. It will begin with the cultural roots of invective, examine Cicero’s role in sharpening the politics of verbal abuse, and follow its evolution in civil wars, popular agitation, and imperial treason trials. By drawing on episodes from the Gracchi to Augustus, and from Catiline to Domitian, the essay will demonstrate how rhetoric blurred the boundary between speech and violence, between insult and execution, ultimately transforming Rome’s political landscape.

The Cultural Roots of Roman Invective

The practice of invective in Rome cannot be understood simply as personal insult. It was embedded within a culture that valued public competition, where political success required not only virtue (virtus) but also the ability to tarnish one’s rivals. From the earliest days of the Republic, the spoken word carried a force that bound communities together or fractured them apart. The art of speech was not ornamental but essential, for the Roman ideal of the citizen-politician demanded mastery of oratory. Within that context, abuse was not a deviation but a constitutive part of political life.

Roman rhetorical training formalized this culture. Students learned suasoriae and controversiae in the rhetorical schools, exercises that demanded sharp attacks on opponents, even to the point of caricature.2 The point was not only to persuade but to dominate. By mastering verbal assault, young elites rehearsed for the brutal exchanges of the Forum. Invective thus became a measure of masculine strength. An opponent cast as effeminate, corrupt, or tyrannical was not merely shamed but stripped of legitimacy in the eyes of his peers and the public.

The vocabulary of insult drew heavily on Rome’s moral code. Accusations of stuprum (sexual immorality), greed, luxury, and effeminacy were common, not because they were always true, but because they struck at the heart of Roman values.3 A man labeled effeminate was assumed to lack the self-control necessary for leadership; one accused of greed endangered the res publica by placing personal gain above civic duty. Such rhetorical strategies transformed political debate into a moral battlefield where reputations could be destroyed more efficiently than by legal prosecution.

This tradition had profound consequences. By normalizing verbal aggression, Romans blurred the line between rhetorical victory and social annihilation. Speech became not only a contest of wit but a form of political warfare in which reputations and lives hung in the balance. The invective was thus both an art and a weapon, shaping the contours of Roman political culture long before Cicero perfected its lethal form.

Cicero and the Politics of Verbal Violence

No figure illustrates the lethal potential of Roman rhetoric more clearly than Marcus Tullius Cicero. His career demonstrates how words, sharpened into weapons, could elevate a statesman to immense prominence while simultaneously sealing his fate. Cicero was a master of invective, adept at weaving accusations of treachery, effeminacy, and tyranny into speeches that inflamed political passions and redefined opponents as existential threats.

His Philippics, modeled on Demosthenes’ speeches against Philip of Macedon, targeted Mark Antony with vitriol that blurred the distinction between political critique and a call for violence. Cicero depicted Antony not as a rival statesman but as a monstrous figure bent on tyranny, a “glutton and drunkard” who “brought the republic to ruin with his lusts.”4 The strategy was clear: by portraying Antony as a corrupt and illegitimate actor, Cicero invited his audience to imagine the elimination of Antony as a patriotic duty.

The consequences were swift and devastating. In the unstable aftermath of Caesar’s assassination, Cicero’s words made reconciliation impossible. When Antony and Octavian reconciled in the Second Triumvirate, Cicero’s relentless invective left him politically isolated and marked for death. In 43 BCE, Antony ensured Cicero’s name appeared on the proscription lists. His brutal end (beheaded, with his hands and tongue nailed to the Rostra) was a grim reminder that violent words often invited violent ends.5 In this macabre spectacle, Antony staged Cicero’s body as a warning: the orator who wielded his tongue as a sword had been silenced by the blade.

Cicero’s career also reveals how Roman rhetoric served not only as verbal combat but as an accelerant for civil conflict. His In Catilinam orations framed Catiline and his followers as a domestic menace so severe that extraordinary measures were justified. By calling Catiline a “disease” within the body politic, Cicero transformed political opposition into pathology, encouraging responses that bypassed normal legal protections.6 Here again, speech prepared the ground for bloodshed by creating categories of enemies who could be destroyed without scruple.

The paradox of Cicero lies in his double role: he was at once the Republic’s greatest defender of lawful order and one of its most dangerous practitioners of violent rhetoric. His example illustrates how deeply words and violence were entangled in Roman politics. To speak was to act, and to speak violently was to court violence in return.

The Rhetoric of Popular Violence

If Cicero and Caesar’s opponents used rhetoric to shape elite politics, other figures turned it outward, aiming their words at the Roman crowd. In the late Republic, oratory spilled into the streets, where language could stir mobs into action and reshape the cityscape itself. Here rhetoric was less a polished art and more a catalyst for collective fury.

The Gracchi brothers illustrate this shift. Tiberius Gracchus, arguing for land redistribution in 133 BCE, framed his opponents as enemies of the people, “beasts of prey” who hoarded Italy’s soil.7 His rhetoric transformed economic grievance into moral outrage, casting reform as a battle between a virtuous citizenry and a corrupt elite. The Senate responded in kind. Led by Scipio Nasica, senators branded Tiberius a tyrant, a word that in Rome amounted to a death sentence.8 When violence erupted, Tiberius was clubbed to death with benches and his body hurled into the Tiber. In this episode, political vocabulary proved fatal: the charge of tyranny erased all possibility of compromise.

His brother Gaius fared no better. A gifted orator, he invoked language of betrayal and oppression to mobilize the plebs against senatorial arrogance. Yet his adversaries met rhetoric with rhetoric, framing him as another tyrant in the making. In 121 BCE, when violence broke out, the Senate issued its first senatus consultum ultimum, the so-called “final decree,” which authorized the killing of citizens without trial. Gaius fled but was hunted down, and thousands of his supporters were executed.9 The cycle of invective and violence, begun in the Forum, ended in blood on the Aventine.

Later populists inherited these strategies. Clodius Pulcher relied on incendiary rhetoric to rally gangs that clashed with those of his rival Milo. The polarization of Roman politics reached a crescendo when Clodius was killed on the Appian Way in 52 BCE. His funeral turned into a riot, and the mob, whipped up by speeches denouncing his murder, carried his body to the Senate house, setting the building ablaze.10 In this moment, rhetoric did not simply incite violence; it directed the crowd’s fury into an act of symbolic destruction, erasing the Senate’s chamber as though to punish the state itself.

These episodes demonstrate how verbal violence, once confined to senatorial debate, saturated Roman civic life. By casting opponents as tyrants, traitors, or enemies of the people, leaders legitimized mob action and stripped adversaries of protection. The crowd became the executor of rhetorical verdicts, and the line between political speech and political murder all but disappeared.

Rhetoric and Civil War: Words Preceding Blades

The late Republic was an age in which language did not merely reflect conflict but actively fueled it. Political disputes were increasingly framed in terms of existential struggle, where compromise was cast as betrayal and opponents were demonized as tyrants or traitors. Words prepared the battlefield long before armies marched, shaping the moral landscape in which violence became not only permissible but necessary.

The assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE offers perhaps the clearest example. Though Caesar’s accumulation of honors and offices provoked anxiety, it was rhetoric that transformed unease into a justification for murder. The charge of “king” was central. In a society that defined itself by the expulsion of its early monarchs, the label “rex” carried with it a mortal stigma.11 By branding Caesar as a tyrant, his opponents framed his assassination not as political violence but as an act of restoration, a tyrannicide sanctified by Roman tradition. The conspirators’ daggers were guided as much by words as by steel.

Earlier, Cicero had demonstrated how this dynamic functioned in his confrontation with Catiline. The In Catilinam speeches did more than denounce an alleged conspiracy; they redefined Catiline as an internal enemy. Cicero’s repeated assertion that Catiline plotted to burn the city and massacre citizens effectively turned suspicion into certainty.12 By speaking the conspiracy into existence, Cicero legitimized the Senate’s extraordinary decree that allowed executions without trial. Here again, rhetoric collapsed the barrier between speech and violence, turning words into warrants for bloodshed.

The civil wars also claimed Cicero himself, whose mastery of verbal violence made him both influential and vulnerable. His Philippics against Mark Antony, filled with charges of tyranny and debauchery, left no room for reconciliation. When Antony secured power through the Second Triumvirate, Cicero’s invective sealed his fate. Proscribed at Antony’s insistence, he was captured and executed in 43 BCE. His head and hands were nailed to the Rostra, a gruesome reversal in which the very instruments of his rhetoric became trophies.13 Cicero’s death demonstrated the ultimate consequence of violent speech in a culture where words and politics could not be separated from blood.

Street politics reinforced this cycle. Figures like Clodius Pulcher used fiery oratory to rally gangs of supporters, transforming rhetoric into mob action. The death of Clodius in 52 BCE was itself the product of this volatile blend of words and violence. His fiery speeches had cultivated loyal crowds that clashed with rivals, and his killing sparked riots so intense that the Senate house itself was burned to the ground.14 Oratory, once a tool for persuasion, had become a means of weaponizing the urban masses.

The civil wars that consumed the Republic were thus not only contests of arms but also wars of words. Propaganda preceded battle, and invective turned political competition into existential combat. By defining rivals as illegitimate, immoral, or tyrannical, Roman statesmen created a climate in which reconciliation was unthinkable and violence inevitable. The blade followed the tongue.

Imperial Rhetoric and the Criminalization of Opposition

With the collapse of the Republic and the rise of Augustus, the role of rhetoric shifted but did not diminish. Where once violent words marked the rough-and-tumble of civic debate, in the imperial era they became a tool of consolidation, aimed at suppressing dissent and redefining loyalty. Rhetoric no longer merely inflamed mobs or justified assassinations; it structured the very boundaries of permissible thought and speech.

Augustus perfected this art through careful restraint. His public rhetoric emphasized moderation, mercy, and restoration, yet it also delegitimized resistance by casting his enemies as disturbers of the peace and betrayers of the Roman people. Suetonius notes that Augustus “spared words in public but used silence as a weapon,” a calculated strategy that marked out opposition without descending into the open invective of Cicero.15 Even so, the message was clear: dissent equaled disloyalty, and disloyalty was a crime.

Under Tiberius, this logic hardened into law. The revival and expansion of maiestas charges, which criminalized offenses against the dignity of the emperor, turned rhetoric into a judicial sword. Tacitus records how even slight words could be twisted into treason, with senators prosecuted for ambiguous remarks or gestures.16 What had once been a rhetorical contest in the Forum was now a matter for the courts, where speech itself could condemn a man to exile or death.

Domitian carried this process further by demanding overt displays of reverence. His self-styling as dominus et deus (lord and god) recast political language into a form of sacral rhetoric that blurred the line between loyalty and worship. Those who refused the formula were marked as traitors.17 In this climate, violent rhetoric no longer prepared the way for physical violence; it became indistinguishable from violence itself, enforcing obedience through fear.

The imperial transformation reveals the dual legacy of Roman invective. The Republic had normalized verbal aggression as a form of political warfare, but the Empire redirected this energy into state control, where rhetoric became law and language itself was policed. In both cases, words shaped the political order with consequences as tangible as the sword.

Rhetoric and Social Consequences Beyond Politics

The consequences of violent rhetoric in Rome were not confined to elite struggles for power. Language shaped the social imagination, defining categories of identity and reinforcing hierarchies that penetrated every aspect of civic life. In this sense, the politics of invective extended far beyond the Forum or Senate house, embedding itself in attitudes toward foreigners, women, and the very boundaries of Roman identity.

One of the most enduring targets of rhetorical aggression was the “barbarian.” Roman generals and statesmen framed external enemies with a language of dehumanization that portrayed them as savage, irrational, and unworthy of mercy. Julius Caesar’s Commentarii de Bello Gallico, though written with an eye to self-promotion, repeatedly describes Gauls and Germans in terms that mark them as violent and unstable, enemies whose defeat was both necessary and just.18 Such portrayals legitimized conquest by casting foreign peoples as existential threats to Roman order, effectively erasing the moral distinction between war and extermination.

Rhetoric also worked to reinforce gender hierarchies. To be labeled effeminate was to be politically disqualified, for Roman masculinity was bound to the capacity for self-control, courage, and authority. Political invective drew on these assumptions, framing opponents as weak or passive by associating them with women or slaves.19 This discourse did not only damage reputations; it perpetuated structures of inequality, normalizing the idea that political legitimacy depended on adherence to rigid gender norms.

Even in private or literary contexts, rhetorical violence shaped Roman culture. Satirists like Juvenal employed hyperbolic attacks on moral corruption, often targeting women, foreigners, and entire social classes. While framed as humor or exaggeration, such rhetoric reinforced stereotypes and hardened prejudices.20 The social body, much like the political body, was disciplined by words that excluded, degraded, and stigmatized.

By extending the logic of invective into the realms of ethnicity, gender, and class, Roman rhetoric embedded violence into the fabric of daily life. Speech was not only a tool for politics but a mechanism of cultural control, teaching Romans whom to trust, whom to fear, and whom to despise. This broader diffusion of rhetorical violence ensured that its effects outlived the Republic, persisting in the moral imagination of the Empire.

Historiographical Reflections

The violent rhetoric of Rome is known to us largely through the pens of historians, whose own choices of language both preserved and amplified the culture they described. Sallust, Tacitus, and Suetonius did not merely record political invective; they participated in it, weaving hostile portrayals into narratives that shaped how posterity understood the Republic and Empire. Their histories remind us that rhetoric is never a neutral window but a crafted frame.

Sallust’s account of Catiline, for instance, cannot be separated from Cicero’s own rhetorical campaign. In The Conspiracy of Catiline, Sallust depicts Catiline as a monstrous figure driven by lust, greed, and madness, embodying every vice that threatened the Republic.21 Such descriptions echoed Cicero’s speeches, reinforcing the idea that Catiline was not a politician but a disease of the body politic. Sallust thus perpetuated Cicero’s rhetorical victory, embedding invective into historical memory.

Tacitus provides another layer. Writing under the Empire, he emphasized how rhetoric became criminalized, noting the climate of fear under Tiberius when even ambiguous words could be construed as treason.22 His prose itself is colored by biting irony and subtle invective, qualities that allowed him to criticize emperors obliquely while demonstrating how rhetorical aggression survived even under authoritarian control. Tacitus’ history is not merely a record of rhetoric but an extension of it, condemning emperors by implication and tone.

Suetonius, though less overtly political, likewise leaned on rhetorical strategies of vilification. In The Twelve Caesars, he assembled anecdotes of moral corruption, sexual deviance, and cruelty to craft enduring images of imperial vice.23 These portraits, though entertaining, rest on the same techniques of invective used in the Forum. By immortalizing emperors in language saturated with scandal, Suetonius extended Rome’s rhetorical violence into biography and cultural memory.

Placed alongside Greek precedents, Roman rhetoric appears particularly extreme. Demosthenes railed against Philip of Macedon, but Athenian invective rarely carried the same immediacy of physical consequence.24 Roman political culture, with its combination of personal honor, urban mobs, and fragile institutions, ensured that rhetorical violence could not remain symbolic. The historians who wrote it down confirmed this entanglement, both as witnesses and as practitioners.

Thus the very sources through which we study Roman rhetoric perpetuate its legacy. The invective that once thundered in the Forum echoes in the pages of Sallust, Tacitus, and Suetonius, shaping how subsequent generations imagine Rome. Historiography is not a detached archive of facts but another stage where violent words have continued their work.

Conclusion

In Rome, words were never merely words. They were instruments of power, sharpened in the crucible of political competition and carried into every corner of civic life. Violent rhetoric did more than win arguments; it reshaped realities, turning opponents into tyrants, conspirators, or monsters who could be destroyed without remorse. From the Gracchi to Cicero, from Caesar to Domitian, the tongue proved as deadly as the sword, preparing the ground for assassinations, civil wars, and imperial terror.

What emerges from this history is a pattern of escalation. The Republic normalized invective as a form of contest, but in doing so it eroded the possibility of compromise. Once rivals were cast as existential threats, violence became inevitable. Under the Empire, this logic was absorbed into law and ritual, where language itself was policed and dissent punished as treason. Even the historians who chronicled these events, from Sallust to Tacitus, extended the tradition, embedding rhetorical violence into the very memory of Rome.

What follows, then, is a cautionary tale. Rome shows us that the boundary between speech and action is fragile, and that violent words can create a climate in which violence seems not only acceptable but necessary. Rhetoric did not merely describe the fall of the Republic and the rise of autocracy; it hastened both. To study the rhetoric of Rome is to confront the enduring danger of language untethered from restraint, a danger as relevant in modern republics as it was in the ancient one.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Catharine Edwards, The Politics of Immorality in Ancient Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 12.

- Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria 2.10.2–5.

- Craig A. Gibson, Interpreting a Classic: Demosthenes and His Ancient Commentators (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 87–88.

- Cicero, Philippics 2.67.

- Plutarch, Life of Cicero 48.

- Cicero, In Catilinam 1.2.

- Plutarch, Life of Tiberius Gracchus 9.

- Appian, Civil Wars 1.14.

- Plutarch, Life of Gaius Gracchus 17.

- Appian, Civil Wars 2.21.

- Suetonius, Julius Caesar 79.

- Sallust, The Conspiracy of Catiline 31.

- Plutarch, Life of Cicero 48.

- Appian, Civil Wars 2.21.

- Suetonius, Augustus 53.

- Tacitus, Annals 1.72.

- Suetonius, Domitian 13.

- Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 6.21.

- Catharine Edwards, The Politics of Immorality in Ancient Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 65.

- Juvenal, Satires 6.

- Sallust, The Conspiracy of Catiline 5.

- Tacitus, Annals 1.72.

- Suetonius, Life of Nero 29.

- Craig A. Gibson, Interpreting a Classic: Demosthenes and His Ancient Commentators (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 112.

Bibliography

- Appian. The Civil Wars. Translated by Horace White. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1913.

- Caesar, Julius. Commentarii de Bello Gallico. Translated by Carolyn Hammond. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. In Catilinam. In Cicero: In Catilinam I–IV. Translated by C. Macdonald. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- ———. Philippics. Translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Edwards, Catharine. The Politics of Immorality in Ancient Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Gibson, Craig A. Interpreting a Classic: Demosthenes and His Ancient Commentators. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

- Juvenal. Satires. Translated by Susanna Morton Braund. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Plutarch. Lives, Volume VII: Demosthenes and Cicero. Alexander and Caesar. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1919.

- Quintilian. Institutio Oratoria. Translated by H. E. Butler. 4 vols. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1920–22.

- Sallust. The Conspiracy of Catiline and The Jugurthine War. Translated by William W. Batstone. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars. Translated by Robert Graves, revised by James B. Rives. London: Penguin Classics, 2007.

- Tacitus. The Annals. Translated by A. J. Woodman. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2004.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.23.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.