While Taylor’s contributions are nothing short of incredible, her story is often overlooked within Civil War history.

By Elizabeth Lindqwister

2019 Liljenquist Fellow

Library of Congress

By Karen Chittenden

Librarian

Library of Congress

By Micah Messenheimer

Curator of Photography

Library of Congress

Introduction

“There are many people who do not know what some of the colored women did during the war.”

Reminiscences, p. 67

Do you know who Susie King Taylor was?

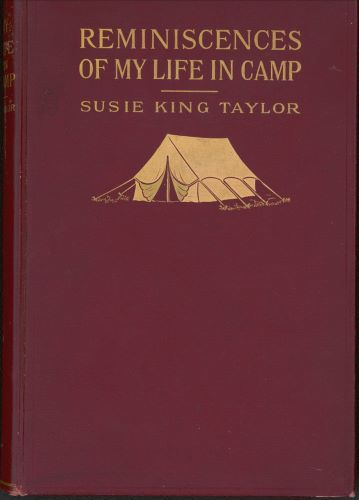

Born into slavery in the Deep South, she served the Union Army in various capacities: officially as a “laundress” but in reality a nurse, caretaker, educator, and friend to the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry (later the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops Infantry Regiment). In 1902, she published these experiences in Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, a Civil War memoir told from the singular perspective of an African American woman.

While Taylor’s contributions to the war are nothing short of incredible, her story is often overlooked within Civil War history.

The Narrative of War

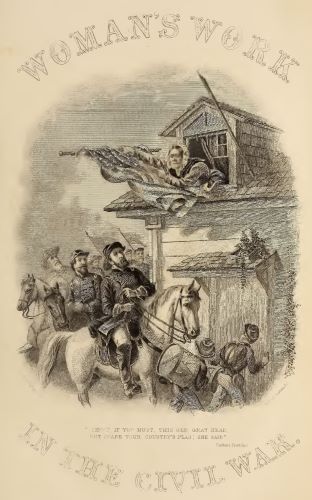

In the postwar 19th century, publications primarily commemorated the war by writing about white soldiers, generals, and presidents—heroic figures celebrated for their bravery in battle or brilliance in war strategy.

Concentrating on these topics recognized the Civil War as a battle of great heroism, loss, and military prowess. Yet, the military focus often ignored the work happening outside of the battles—namely, what women, families, and people of color gave to the war cause.

For African American nurses like Taylor, their contributions to the war were not given space in the American memory. Even when historians began writing about women and children, the achievements of most African American women surfaced slowly.

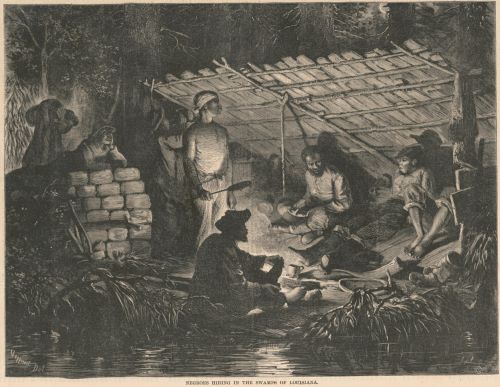

But memoirs, letters, and oral narratives by African Americans provide compelling insights and testimony. Often known as “slave narratives,” these works are rich primary sources that capture the lived experiences of African Americans in Antebellum and post Civil War America.

Taylor wrote one such narrative in 1902. Titled Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, the 83-page memoir depicts her life as a slave, a freed woman, an educator and nurse, and a Black woman living in the postwar South.

Early Years

Susie King Taylor (née Baker) was born into slavery on August 6, 1848, at the Grest Plantation in Liberty County in coastal Georgia. Her mother was a domestic servant.

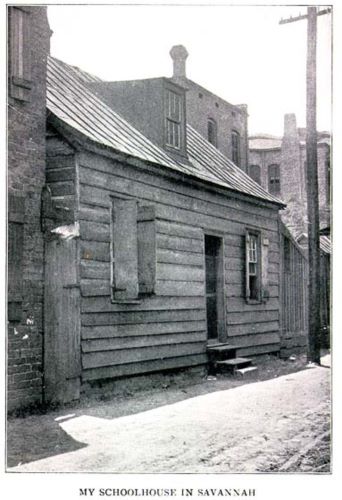

By age seven, Taylor was allowed to move to Savannah, Georgia, to live with her grandmother, Dolly. Most of her childhood was spent with two of her eight siblings and with Grandmother Dolly, who encouraged Taylor to learn to read and write.

At this time, Georgia had severe restrictions on education for freed and enslaved African Americans. Clandestine schooling was the only way an African American child could get an education in the Antebellum South. Taylor’s grandmother arranged for her to attend two secret schools taught by free African American women and family friends.

By the time the Civil War broke out in 1861, Taylor was an educated young woman so accomplished that she had surpassed the level of knowledge of her first teachers in Georgia.

Freedom

“I wanted to see these wonderful ‘Yankees’ so much, as I heard my parents say the Yankee was going to set all the slaves free.”

Reminiscences, p. 8

By April 1862, Taylor had moved back with her mother in Liberty County. Encroaching Union forces in the Eastern Theater of the Civil War made life in Savannah increasingly dangerous.

Skirmishes and battles were in full force now, and rumors about freedom and “the Yankees” reached African Americans in the Deep South.

Taylor’s hopes about freedom and the Yankees soon came true. Union forces attacked the Confederate-held Fort Pulaski on April 1, 1862.

“I remember what a roar and din the guns made. They jarred the earth for miles. The fort was at last taken by them.”

Reminiscences, pp. 8-9

At this time, it was not uncommon for slaves to escape in the chaos of a battle or invasion. Taylor and her uncle’s family fled to St. Catherines Island, later traveling south to St. Simons Island on the Union ship U.S.S. Potomska.

While aboard the Potomska, Taylor impressed the ship’s commander Lieutenant Pendleton G. Watmough with her reading, writing, and masterful sewing abilities—skills often not taught to women of color in the South.

“He was surprised by my accomplishments (for they were such in those days), for he said he did not know there were any negroes in the South able to read or write.”

Reminiscences, p. 9

Upon their arrival at St. Simons Island, Watmough immediately arranged for Taylor to take up a teaching position at a children’s school. During the day, she taught reading and writing to upwards of 40 children and even more adults who came to her schoolhouse at night.

“[They] came to me nights, all of them so eager to learn to read, to read above anything else.”

Reminiscences, p. 11

At just 14 years of age, Taylor had become the first African American known to teach at a freedmen’s school in Georgia.

At War

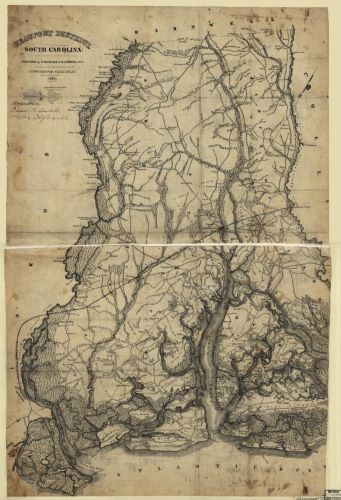

Overview

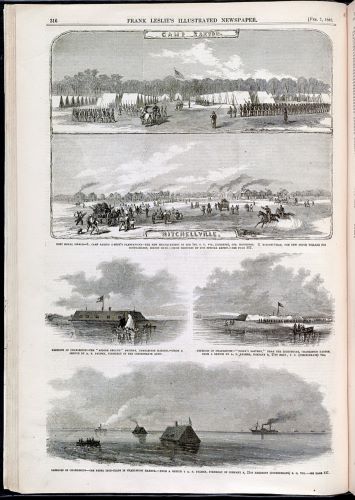

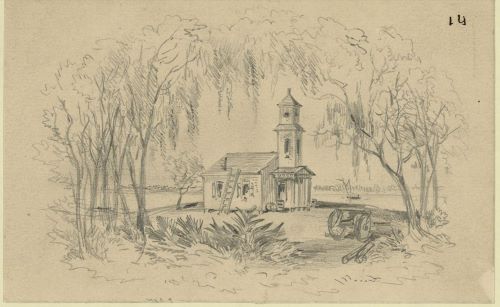

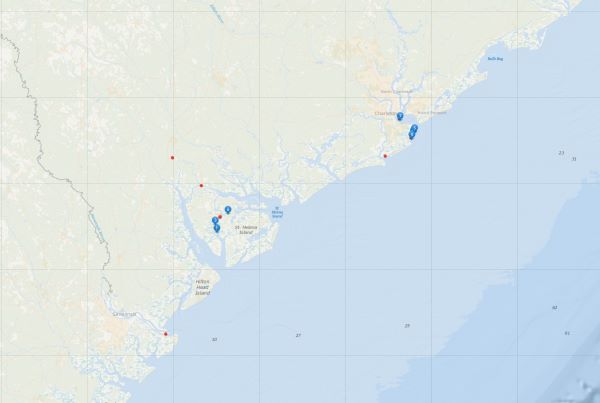

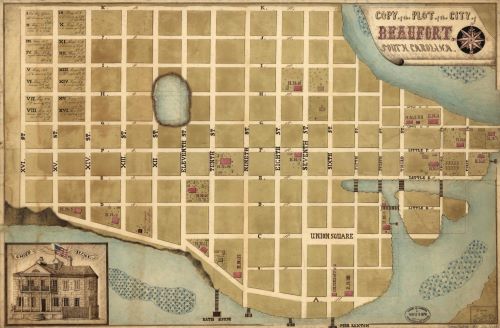

Taylor moved to Beaufort, South Carolina, in late fall 1862, where the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment had formed at Camp Saxton. One of the first African American regiments, the 1st South Carolina was later reorganized as the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops Infantry Regiment.

Among those who volunteered for the regiment was Edward King, whom Taylor would soon marry.

Forming a Colored Regiment

The 1st South Carolina Volunteers was formed in the fall of 1862 in Beaufort, South Carolina. The creation of this regiment was made not solely because of a need for increased troops; its existence reflected the Union Army’s slowly-changing mindset toward African American soldiers.

Early in the war, the Union usually sent escaped African Americans back to their slave owners.

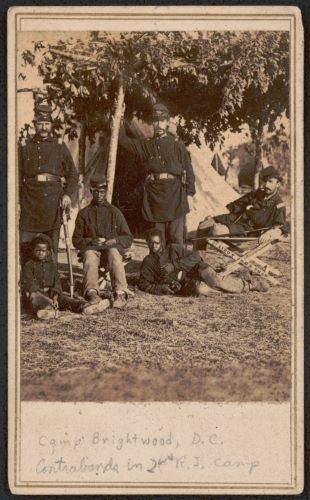

That changed when the Union Army decided to classify escaped slaves as “contrabands of war.” They supported the Union Army mainly by working as laborers. As the war progressed, the Union needed more soldiers. Because the escaped men were labeled as “contraband,” they were considered “property” taken from Confederate lines. This distinction allowed the Army to conscript former slaves as military laborers, without being legally obliged to return them to the Confederates.

By the fall of 1862, African Americans were no longer considered property by the Union. They were allowed to enlist—albeit under segregated units—without fear of being forced into servitude.

“The first colored troops did not receive any pay for eighteen months, and the men had to depend wholly on what they received from the commissary.”

Reminiscences, pp. 15-16

The 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment was formed in November 1862, just two months shy of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Most of the men enlisted were Gullah men from Georgia and South Carolina.

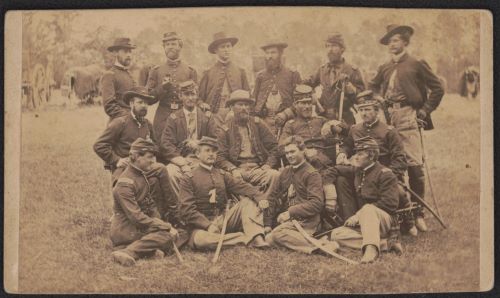

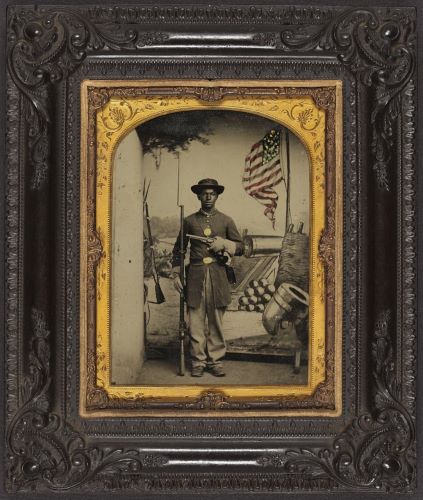

The image above shows African American soldiers with Major Samuel K. Smith Thompson, who served as Lieutenant in the 54th U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War. It is possible that these soldiers also served in a segregated regiment during the war.

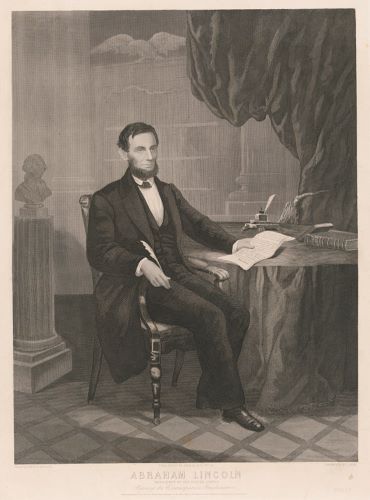

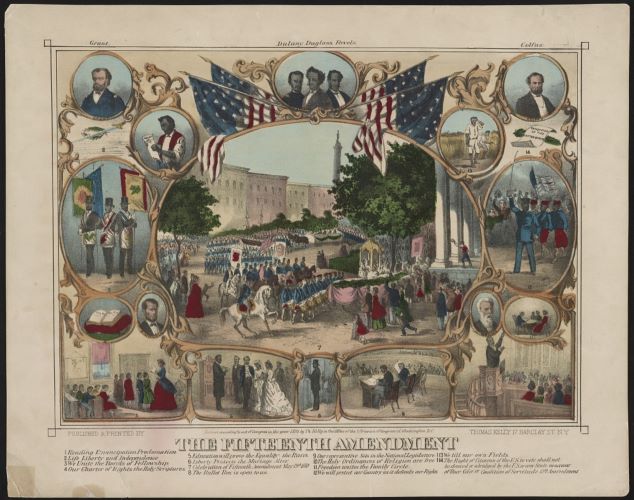

Emancipation Proclamation

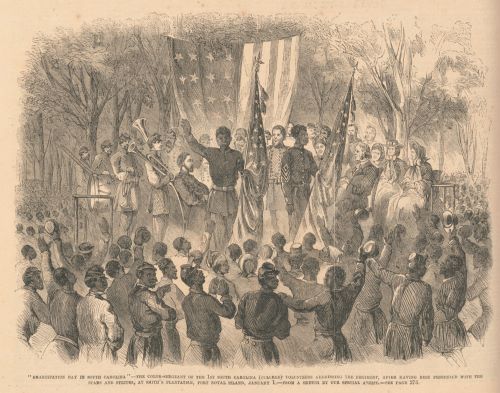

With the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, African American infantries were given the stars and stripes and full colors to formally recognize their position within the Union Army.

“On the first of January, 1863, we held services for the purpose of listening to the reading of President Lincoln’s proclamation…and the presentation of two beautiful stands of colors…

It was a glorious day for us all, and we enjoyed every minute of it…many, no doubt, dreamt of this memorable day.”

Reminiscences, p. 18

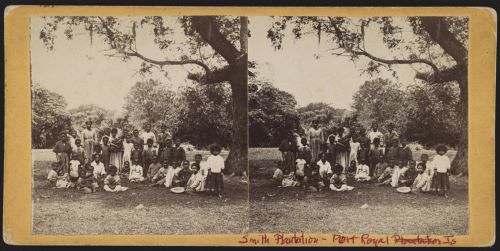

The image above depicts a Black sergeant of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers addressing the regiment on Smith Plantation.

He is holding the stars and stripes given to the regiment after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Who’s Who in the 1st South Carolina Infantry

Taylor recorded every step of the journey for the 1st South Carolina Volunteers from its days in training camp to its skirmishes in Florida. Her memoir reveals that she worked with men and women of many ranks throughout this time period.

The 1st South Carolina was comprised of Black soldiers, yet commanded by white Union officers—a common practice for segregated infantries during the war.

Taylor was extremely fond of her regiment commanders and wrote frequently of her interactions with them.

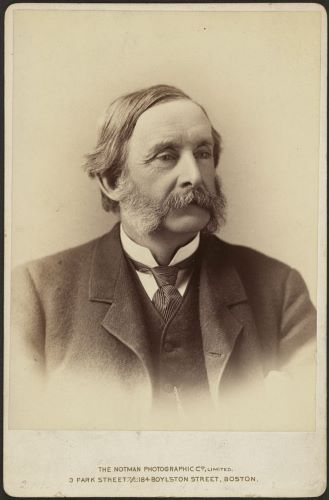

Included in her writings is Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a noted abolitionist and commander of the regiment in its early days. Higginson was largely responsible for training the soldiers at the beginning of the war, when the regiment was based at Camp Saxton, located on the Smith Plantation in Port Royal, South Carolina. He kept a journal of the regiment’s trials and travels, publishing it in the Atlantic after the war.

Colonel Higginson wrote these notes in the fall of 1862:

“… the aptitude of the freed slaves for military drill and discipline, their ardent loyalty, their courage under fire, and their self-control in success, contributed somewhat towards solving the problem of the war, and towards remoulding the destinies of two races on this continent.”

“Leaves from an Officer’s Journal”

Higginson was eventually replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Charles T. Trowbridge, who had worked with the regiment previously as a captain and a recruiting officer. He was respected within the regiment; Taylor wrote, “No officer in the army was more beloved than our late lieutenant-colonel.”

Reminiscences, p. 46

“We thought there was no one like [Trowbridge], for he was a ‘man’ among his soldiers…I shall never forget his friendship and kindness toward me, from the first time I met him to the end of the war.”

Reminiscences, p. 45

He commanded the South Carolina Volunteers until they were mustered out in 1866.

When the 1st South Carolina Volunteers Regiment was mustered in, women naturally joined the cause. Medical aid, cleaning duties, and general domestic help were needed in battle and many family members and freed women filled these positions for the regiment.

One of many women working with the regiment was Harriet Tubman, who was a major voice in the abolition and later the women’s suffrage movements. She served as a nurse, scout, and spy for the 1st South Carolina Volunteers. It is unclear whether she and Taylor knew each other.

Susie King Taylor in the Regiment

When Taylor joined the regiment, she was called a “laundress”.

In the Civil War, this meant little more than a woman who followed a regiment, cleaning clothes and sometimes filling canteens.

The typical laundress presided over soapy tubs stained red and black with blood and grit, their hands perpetually pruned and backs inevitably sore. They were not often literate and were stereotyped as “loose women.”

“Laundress” was thus a title almost wholly unfit for Susie King Taylor. Her work during the Civil War certainly included washing clothes, but also extended into the realm of gun maintenance, nursing, and education—positions befitting her experience as a schoolteacher.

Taylor likely dressed hundreds of wounds and encountered numerous diseases. Cholera, diarrhea, malaria, measles, pneumonia, and typhoid were common in camps. But she never contracted these diseases, nor did she ever stop working for fear of getting sick.

Taylor describes her scenes from camp life as follows:

“I was enrolled as company laundress, but I did very little of it, because I was always busy doing other things through camp, and was employed all the time doing something for the officers and comrades.”

Reminiscences, p. 35

“I learned to handle a musket very well while in the regiment, and could shoot straight and often hit the target. I assisted in cleaning the guns and used to fire them off, to see if the cartridges were dry, before cleaning and reloading, each day.

I thought this great fun. I was also able to take a gun all apart, and put it together again.”

Reminiscences, p. 26

“I was not in the least afraid of the small-pox. I had been vaccinated, and I drank sassafras tea constantly, which kept my blood purged and prevented me from contracting this dread scourge…”

Reminiscences, p. 17

“Our boys would say to me sometimes ‘Mrs. King, why is it you are so kind to us? you treat us just as you do the boys in your own company…

…you took an interest in us boys ever since we have been here, and we are very grateful for all you do for us.'”

Reminiscences, pp. 29-30

Not Just a “Laundress”

Perhaps Taylor’s most important service to the 1st South Carolina Volunteers was her role as an educator. In between dressing wounds and cleaning uniforms, Taylor taught reading and writing to the men of the regiment.

“I taught a great many of the comrades in Company E to read and write, when they were off duty. Nearly all were anxious to learn… I was very happy to know my efforts were successful in camp, and also felt grateful for the appreciation of my services.”

Reminiscences, p. 21

In a 1902 letter republished in Reminiscences (p. xiii), Colonel Trowbridge apologized for the “technicality” of Taylor’s identification as only a laundress, rather than a nurse. Such a “technicality” led to her never receiving pay or a pension.

“It seems strange how our aversion to seeing suffering is overcome in war,—how we are able to see the most sickening sights, such as men with their limbs blown off and mangled by the deadly shells, without a shudder; and instead of turning away, how we hurry to assist in alleviating their pain, bind up their wounds, and press the cool water to their parched lips, with feelings only of sympathy and pity.”

Reminiscences, pp. 31-32

Yet, Taylor’s significant contributions to the war are undeniable. It is for these reasons that Taylor is now more commonly recognized as the first African American Army nurse, and not as a laundress.

Words from the Battlefront

Setting Up Camp

The 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry was formed in 1862 under Col. T.W. Higginsworth and Col. C.T. Trowbridge.

They left from St. Simons Island to start training at Camp Saxton, located on the Smith planation, or “Old Fort,” in Port Royal, South Carolina.

“… [Captain Trowbridge] was very much pleased at the bravery shown by these men. He found me at Gaston Bluff teaching my little school, and was much interested in it. When I knew him better I found him to be a thorough gentleman and a staunch friend to my race.”

“I had a number of relatives in this regiment—several uncles, some cousins, and a husband in Company E, and a number of cousins in other companies.”

Reminiscences, pp. 15-16

Ordered to Jacksonville

By March 1863, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers received orders to march south to Florida. There, they encountered Confederates in blackface, attempting to dupe and then ambush the all-Black regiment.

“They were hiding behind a house about a mile or so away, their faces blackened to disguise themselves as negroes, and our boys, as they advanced toward them, halted a second, saying,

‘They are black men! Let them come to us, or we will make them know who we are.’

With this, the firing was opened and several of our men were wounded and killed. The rebels had a number wounded and killed. It was through this way the discovery was made that they were white men.”

Reminiscences, pp. 22-23

A Visit to Beaufort Hospital

Taylor’s nursing duties extended beyond the work she did in the regiment camps. She often visited nearby hospitals to provide aid in any way she could.

It is unclear which of the Beaufort hospitals Taylor visited, as there were more than a dozen of them operating in the height of the Civil War.

But because Taylor was an African American woman working for the 33rd U.S.C.T., it is likely that she spent significant time in the hospital designated for fugitive slaves or wounded African American soldiers.

While visiting Beaufort, Taylor met Clara Barton, founder of the Red Cross.

“When at Camp Shaw, I visited the hospital in Beaufort, where I met Clara Barton. There were a number of sick and wounded soldiers there, and I went often to see the comrades.

Miss Barton was always very cordial toward me, and I honored her for her devotion and care of those men.”

Reminiscences, p. 30

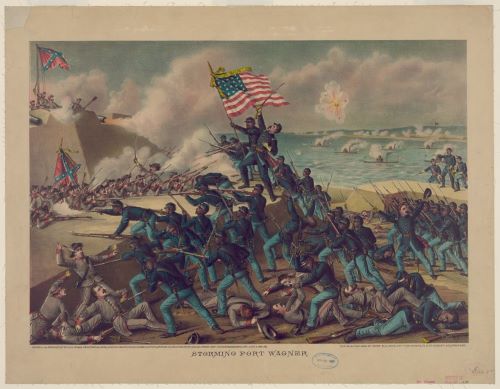

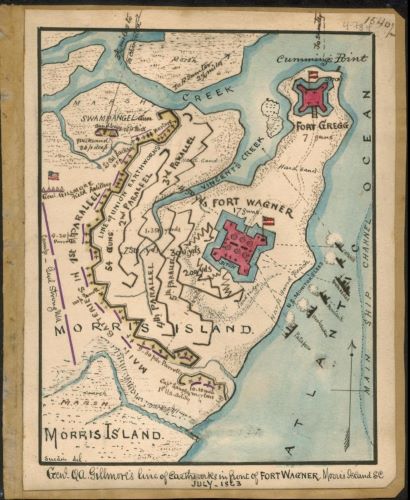

A Siege on Fort Wagner

By 1864, Fort Wagner had already been the grounds for a major clash between Confederate and Union forces. Notably, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, an African American regiment, was at the head of the 1863 charge.

Taylor’s regiment was stationed near Fort Wagner. In her memoir, she described the horrors she witnessed while on Morris Island.

“Outside of the fort were many skulls lying about; I have often moved them one side out of the path. The comrades and I would have quite a debate as to which side the men fought on.

Some thought they were the skulls of our boys; others thought they were the enemy’s; but as there was no definite way to know, it was never decided which could lay claim to them.

They were a gruesome sight, those fleshless heads and grinning jaws, but by this time I had become accustomed to worse things and did not feel as I might have earlier in my camp life.”

Reminiscences, p. 31

Taking on Fort Gregg

In mid-1864, the 33rd U.S.C.T. prepared to take on Fort Gregg, located near Fort Wagner on Morris Island.

“About four o’clock, July 2, the charge was made. The firing could be plainly heard in camp… Then others of our boys [arrived], some with their legs off, arm gone, foot off, and wounds of all kinds imaginable.

They had to wade through creeks and marshes, as they were discovered by the enemy and shelled very badly. A number of the men were lost, some got fastened in the mud and had to cut off the legs of their pants, to free themselves.

My work now began. I gave my assistance to try to alleviate their sufferings.”

Reminiscences, p. 34

“Cast Away”

In 1864, Taylor almost lost her life while aboard a capsizing transport ship. She was on her way from Hilton Head Island to Beaufort. She was rescued on Christmas Day.

“It was nearly dark before we had gone any distance, and about eight o’clock we were cast away and were only saved through the mercy of God. I remember going down twice. As I rose the second time, I caught hold of the sail and managed to hold fast…

…we drifted and shouted as loud as we could… But it was in vain, we could not make ourselves heard, and just when we gave up all hope, and in the last moment (as we thought) gave one more despairing cry, we were heard at Ladies’ Island…

They found us at last, nearly dead from exposure.”

Reminiscences, pp. 37-39

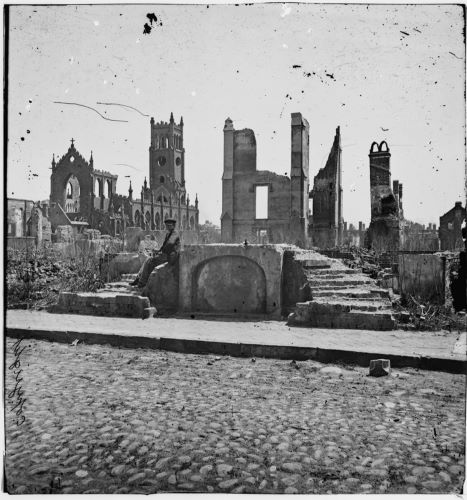

The Capture of Charleston

Hot on the heels of fleeing Confederates, Company E engaged in various skirmishes throughout the region. There, they encountered fewer Confederates, but met many embittered white Southerners.

“… the ‘rebs’ had set fire to the city and fled, leaving women and children behind to suffer and perish in the flames. The fire had been burning fiercely for a day and night.

It was a terrible scene. For three or four days the men fought the fire, saving the property and effects of the people, yet these white men and women could not tolerate our black Union soldiers, for many of them had formerly been their slaves…

… and although these brave men risked life and limb to assist them in their distress, men and even women would sneer and molest them whenever they met them.”

Reminiscences, p. 42

Ambush in Augusta

The 33rd U.S.C.T. finished off its service in various skirmishes throughout South Carolina and Georgia:

“The regiment remained in Augusta for thirty days, when it was ordered to Hamburg, S.C., and then on to Charleston.

It was while on their march through the country, to the latter city, that they came in contact with the bushwhackers (as the rebels were called), who hid in the bushes and would shoot the Union boys every chance they got.”

Reminiscences, p. 43

Confederate Run-Ins

“Other times they would conceal themselves in the cars used to transfer our soldiers, and when our boys, worn out and tired, would fall asleep, these men would come out from their hiding places and cut their throats.

Several of our men were killed in this way, but it could not be found out who was committing these murders until one night one of the rebels was caught in the act.”

Reminiscences, pp. 43-44

Mustered out on Morris Island

Returning to Morris Island in January of 1866, the 33rd U.S.C.T. Volunteer Infantry was mustered out that same month. Col. Charles T. Trowbridge delivered this mustering out message to the soldiers:

“On the 9th day of May, 1862, at which time there were nearly four millions of your race in bondage, sanctioned by the laws of the land and protected by our flag,—on that day, in the face of the floods of prejudice that well-nigh deluged every avenue to manhood and true liberty, you came forth to do battle for your country and kindred.”

Reminiscences, p. 47

Trowbridge continued:

“And from that little band of hopeful, trusting, and brave men who gathered at Camp Saxton, on Port Royal Island, in the fall of ’62, amidst the terrible prejudices that surrounded us, has grown an army of a hundred and forty thousand black soldiers, whose valor and heroism has won for your race a name which will live as long as the undying pages of history shall endure…

The prejudices which formerly existed against you are well-nigh rooted out.

The nation guarantees to you full protection and justice… To the officers of the regiment I would say, your toils are ended, your mission is fulfilled, and we separate forever.”

Reminiscences, pp. 47-49

Postwar Inequality

Taylor and her husband left the war behind once the 33rd Volunteer Infantry was mustered out in early 1866. Unlike white veterans and nurses, the Kings never received a pension for their services.

Though the war had ended, the Kings would soon find that life in the postwar South was extremely challenging and dangerous for African Americans. Edward King was unable to secure a job as a carpenter—a position he was highly skilled at—because of his race. King then took work as a longshoreman, but tragically passed away from a docking accident in September 1866. He died just a few months before the birth of his son.

Taylor hoped to continue teaching after the war. She opened three separate schools, two in Savannah and one in Liberty County, Georgia, between 1866 and 1868. She was not able to support herself and her son while operating schools because she could not compete with free schools that were opening for African Americans.

Finally, Taylor left her son with her mother and turned to working as a domestic servant, which led her to positions in the South and the North.

Writing that her “interest in the boys in blue had not abated,” (Reminiscences, p. 59) Taylor also dedicated much of her postwar life to helping veterans and their families. She joined the Women’s Relief Corps, Auxiliary to the Grand Army of the Republic, and organized Corps 67.

Susie King Taylor passed away in October 1912.

“Thoughts on Present Conditions”

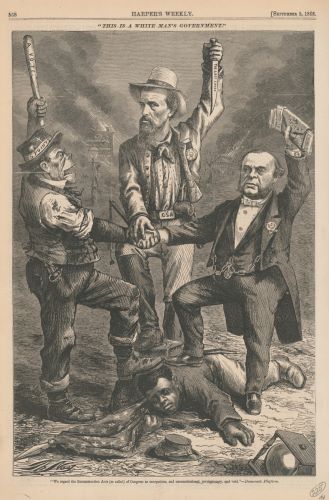

Taylor’s life story cannot be told without recognizing the racial context that shaped her life before, during, and especially after the Civil War.

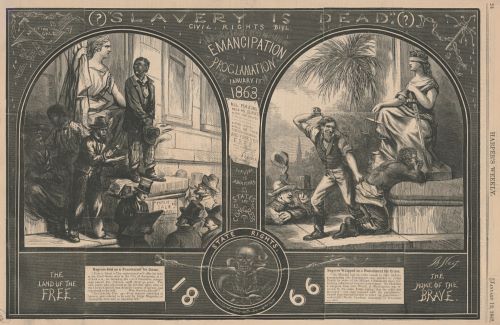

Although Taylor faced unimaginable difficulties throughout the war, she encountered just as many challenges after the war’s close. The signing of the Emancipation Proclamation and the Union’s victory in the Civil War meant progress for racial equality in the United States, but could not alleviate the racial divide still haunting the wounded nation.

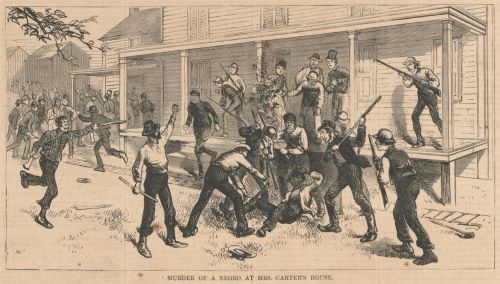

The end of slavery was the prelude to new racist laws and a justice system that refused to protect the interests and bodies of Black Americans. Taylor writes about this postwar discrimination throughout her memoir. She pauses at the end to reflect on the state of race relations in 20th century Jim Crow America.

“I wonder if our white fellow men realize the true sense or meaning of brotherhood? For two hundred years we had toiled for them; the war of 1861 came and was ended, and we thought our race was forever freed from bondage, and that the two races could live in unity with each other, but when we read almost every day of what is being done to my race by some whites in the South, I sometimes ask, ‘Was the war in vain? Has it brought freedom, in the full sense of the word, or has it not made our condition more hopeless?'”

Reminiscences, p. 61

The passing of the thirteenth, fourteen, and fifteenth amendments throughout the 1870s abolished slavery and granted some legal rights to African Americans.

Some of these protections were honored by white people in the North, and Taylor writes about how her experiences in Boston differed dramatically from that of the South.

“I have looked for liberty and justice, equal for the black as for the white; but it was not until I was within the borders of New England, and reached old Massachusetts, that I found it.

Here is found liberty in the full sense of the word, liberty for the stranger within her gates, irrespective of race or creed, liberty and justice for all.”

Reminiscences, pp. 62-63

Reconstruction was unpopular in the post-Confederate, post-slavery South. Many white Southerners saw it as an embarrassment to the former Confederacy and took it upon themselves to carry out the legacy of slavery in every way possible.

This included the creation of “black codes” in the South. These rules all but forced African Americans into servile and laboring positions—as it was during the time of legal slavery—and severely restricted their rights as citizens.

“[Edward King] was a boss carpenter, but being just mustered out of the army, and the prejudice against his race being still too strong to insure him much work at his trade, he took contracts for unloading vessels.”

Reminiscences, p. 54

The passage of the 1896 Jim Crow laws solidified the South’s ongoing racism.

“Separate but equal” became the mantra and Southern Blacks received virtually no protections in the face of civil suits.

In Taylor’s eyes, during an 1898 trip to Louisiana:

“I asked a white man standing near (before I got my train) what car I should take.

‘Take that one,’ he said, pointing to one.

‘But that is a smoking car!’

‘Well,’ he replied, ‘that is the car for colored people.’

I went to this car, and on entering it all my courage failed me. I have ridden in many coaches, but I was never in such as these.”

Reminiscences, p. 69

The things Taylor saw in the Jim Crow South were horrifying. She wrote frequently of the discrimination she faced, and how such treatment rubbed against her wartime patriotism for America.

The Ku Klux Klan came into power in the 1870s and 1880s, and became a deadly, racist group that protested Reconstruction and terrorized African Americans.

“‘Each morning you can hear of some negro being lynched;’ and on seeing my surprise, he said,

‘Oh, that is nothing; it is done all the time. We have no rights here. I have been on this road for fifteen years and have seen some terrible things.'”

Reminiscences, p. 71

“They say, ‘One flag, one nation, one country indivisible.’ Is this true? Can we say this truthfully, when one race is allowed to burn, hang, and inflict the most horrible torture weekly, monthly, on another?

No, we cannot sing ‘My country, ’tis of thee, Sweet land of Liberty!’ It is hollow mockery.

The Southland laws are all on the side of the white, and they do just as they like to the negro, whether in the right or not.”

Reminiscences, pp. 61-62

“In this ‘land of the free’ we are burned, tortured, and denied a fair trial, murdered for any imaginary wrong conceived in the brain of the negro-hating white man.”

Reminiscences, p. 61

Having lived in both the North and the South, Taylor understood what it meant to be a Black woman in two completely different worlds, all within one country. Alongside her fond memories of white Union Army generals are written testimonies to the racism she witnessed throughout the South.

“That is the way they do here,” a Southerner told Taylor.

For even as the North presented a marginally better life for African Americans, the South perpetuated the violence of enslavement in every way short of pre-proclamation bondage.

The frustrating contradictions of America’s founding and emancipation are woven throughout Taylor’s reflections, emphasizing the hopeful yet somber outlook she had for the life in front of her.

“Can we forget those cruelties? No, though we try to forgive and say, ‘No North, no South,’ and hope to see it in reality before the last comrade passes away.”

Reminiscences, p. 68

Memorializing Forgotten Heroes

Taylor forged a path for African American nursing and education – both during and after the war. And yet, many Americans don’t know about her achievements or her memoir.

Unlike other Civil War nurses, who received sizable pensions and character sketches in commemorative history books, Susie King Taylor’s life went largely unnoticed in Reconstruction America.

Historians note that Reconstruction-era writers—particularly those hailing from the North—did little to ease race-based inequalities through their choice of subject matter. By writing only about upper- and middle-class white nurses, many war biographers “reproduced the sectional divide and obliterated the memory of people of color.” Women at the Front, pp. 12-13.

It wasn’t until Taylor published her diary and memoir in 1902 that the public could learn the extent to which she and other African Americans served the Union Army.

Taylor’s initial reluctance to publish a memoir about her time as a nurse reflects the state of historical remembrance after the war’s end. By placing the experiences of African Americans at the forefront of the Civil War, Taylor urged history to remember the thousands of Black soldiers and Black nurses who sacrificed their lives for the war cause.

At a time when history was written in joyful commemoration, her work described America’s ongoing racial divide and demanded equal treatment and historical remembrance of African Americans.

“Justice we ask,—to be citizens of these United States, where so many of our people have shed their blood with their white comrades, that the stars and stripes should never be polluted.”

Reminiscences, pp. 75-76

Sources

- American Battlefield Trust. “Bushwhackers and Jayhawks.” Accessed August 19, 2019. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/bushwhackers-and-jayhawks

- Bartoletti, Susan Campbell. They Called Themselves the K.K.K.: The Birth of an American Terrorist Group. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010.

- Bradley, Anders. “The First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment (1862-1866).” BlackPast, September 9, 2018. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/first-south-carolina-volunteer-infantry-regiment-1862-1866/

- Brockett, L. P. (Linus Pierpont). Woman’s Work in the Civil War: a Record of Heroism, Patriotism and Patience. Philadelphia: Zeigler, McCurdy, & Co., 1867.

- Coates, Ta-Nehisi. “Susie King Taylor.” The Atlantic, August 10, 2010. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2010/08/susie-king-taylor/61113/

- Davis, Jingle. Island Time: An Illustrated History of St. Simons Island, Georgia. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2013.

- Foner, Eric. “Selective Memory.” Review of Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory by David W. Blight. New York Times, March 4, 2001. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/03/04/books/selective-memory.html

- Forbes, Ella. African American Women During the Civil War. New York: Garland Publishing, 1998.

- Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. “Leaves From an Officer’s Journal.” The Atlantic, November 1864. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1864/11/leaves-from-an-officers-journal/308755/

- History.com editors. “Ku Klux Klan.” History. October 29, 2009. https://www.history.com/topics/reconstruction/ku-klux-klan#section_1

- Pilgrim, David. “What Was Jim Crow?” Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Ferris State University, September 2000. https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/who/index.htm

- National Archives. “Black Soldiers in the U.S. Military During the Civil War.” https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/blacks-civil-war

- National Park Service. Fort Scott National Historic Site. “Laundress-Historic Background.” July 25, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/fosc/learn/education/laundress5.htm

- National Park Service. “Living Contraband – Former Slaves in the Nation’s Capital During the Civil War.” August 15, 2017. https://www.nps.gov/articles/living-contraband-former-slaves-in-the-nation-s-capital-during-the-civil-war.htm

- National Park Service. Fort Pulaski National Monument. “Susie King Taylor,” March 30, 2019. Accessed August 5, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/people/susie-king-taylor.htm

- Schultz, Jane E. Women at the Front. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2004. https://lccn.loc.gov/2003024944

- Tambo, D. and E. Fields. Guide to the 1st South Carolina / 33 Rd U.S. Colored Troops Records. Department of Special Collections, Davidson Library, University of California. Santa Barbara, 2002. https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0d5n99qh/entire_text/

- Taylor, Susie King. Reminiscences of My Life in Camp. Boston: Susie King Taylor, 1902. https://lccn.loc.gov/02030128 Available online at: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/gdc/scd0001/2008/20081001004re/20081001004re.pdf

- Ware, Susan, editor. Forgotten Heroes : Inspiring American Portraits from Our Leading Historians. New York: Free Press, 1998.

Originally published by the United States Library of Congress to the public domain.