University educated physicians were only a small minority of all medical professionals and healers.

By Dr. Timo Joutsivuo

Author and Historian

Introduction

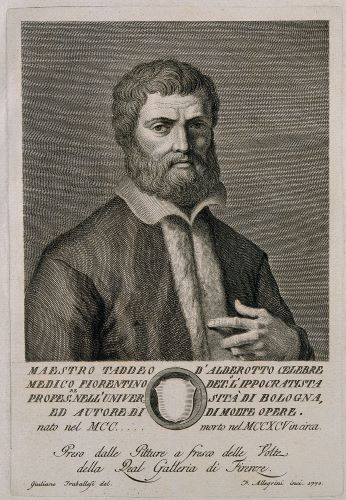

Marquess of Ferrara Obizzo II d’Este (about 1247–1293) was a well known nobleman and a leader of the Florentine political party, the Black Guelfs. He was also mentioned by Dante Alighieri in his Divine Comedy. Dante placed Obizzo in Hell among the tyrants, who “indulged in bloodshed and rapine.”1 In the late thirteenth century Obizzo II d’Este turned for help to the famous Florence-born Bolognese professor of medicine, Taddeo Alderotti (1205/1215–1295). The reason was that the Marquess was suffering from severe melancholy with one special symptom, insomnia, which was the reason why he had not been able to sleep properly in two years.2

Taddeo Alderotti did what was asked of him and wrote a special regimen for the Marquess, which was later used as a general guide for taking care of melancholic patients. This was because the regimen was included in Taddeo’s collection of case studies called consilia. This collection included a total of 185 case studies, and it became very popular as a medical handbook.

This article will investigate Taddeo Alderotti’s recommendation to Obizzo d’Este and the reasoning behind his choice of cure. This inevitably involves a brief overview of what was understood by melancholy in medicine at the turn of the fourteenth century. Therefore, Alderotti’s more theoretical writings will be examined alongside more practical case studies, which do not contain any systematic study of the causes and signs of a particular disease. Taddeo Alderotti’s theoretically oriented texts include his commentaries on university medical textbooks, Hippocratic Aphorisms, Galen’s Tegni and Isagoge, which was written by the Nestorian Christian physician and scholar Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873), known as Joannititus in the West. Galen’s Tegni was a very important textbook on the theory of medicine in medieval universities and Isagoge was an Arabic short introduction into Galenic medicine.

To get a deeper understanding of the matter the ideas of two other contemporary physicians are also investigated: Pietro Torrigiano (d. a. 1319), who was one of Alderotti’s students and the writer of a magnum opus of scholastic medicine, a much-praised commentary on Galen’s Tegni,3 and Bernard de Gordon (d. 1320), who taught medicine at the University of Montpellier. Bernard wrote more practically oriented treatises on medicine, and his most famous book, Lilium medicine, was intended as an aid in medical practice for his younger colleagues. With Bernard de Gordon it is possible to compare the contemporary ideas of melancholy in the two most important medical centres at the turn of the fourteenth century. Moreover, both Taddeo Alderotti and Bernard de Gordon were very influential during their lifetimes and all three had a powerful influence on fourteenth-century university medicine.

It is, however, worth remembering that university educated physicians were only a small minority of all professionals or part-time healers working on medicine at the turn of the fourteenth century. In most parts of Europe, especially in rural areas where the majority of the people lived, there were probably only a few physicians, if any. Beside university educated physicians, who were called “rational and learned doctors” by Roger French,4 a number of different kinds of practitioners offered their services: surgeons, barber-surgeons, barbers, apothecaries, empirics often specializing in treating one special surgical condition, and professional midwifes. Moreover, family members, neighbours and friends could serve as casual healers. Priests and mendicants also helped the sick, although the church had banned them from practicing some forms of medical care. In the fourth lateral council in 1215 surgical operations, for example, were forbidden from the clergy.5 Thus, the ideas about melancholy presented in this chapter reflect the scholastic approach and do not necessarily tell the whole story regarding the medieval concept of melancholy.

I propose to discuss specific aspects of theory related to melancholy: firstly, melancholy as an illness, secondly melancholy as a normal disposition of man, thirdly the ageing process and its relationship to melancholy, and finally the methods used to treat melancholy, before proceeding to my conclusions. First, however, it is necessary to specify how scholastic physicians defined health.

The Idea of Health at the Universities

At the turn of the fourteenth century a significant change in teaching in medicine at universities occurred. Since the twelfth century this medical instruction was based on only a few texts, the most important being Tegni, Isagoge and the Hippocratic treatises Aphorisms and Prognostics. In the later thirteenth century more books were introduced into the medical curriculum. One important text was Canon, written by the Persian physician and scientist ibn Sīnā or Avicenna (d. 1037) as he was known in the Latin West. Canon was a large book that covered both theoretical and the practical knowledge of medicine. Moreover, more of Galen’s works were included in the curriculum. Many of these were already translated into Latin in the twelfth century, but their use in the instruction of medicine was delayed because of their complexity and unsystematic structure. In the thirteenth century, after the permanent establishment of medical faculties, interest in Galen’s works grew, especially in the universities of Paris, Montpellier and Bologna, which were the centres of scholastic medicine.

The second-century physician Galen had written an enormous number of medical texts that handled almost every aspect of medicine. To many in the late thirteenth century it seemed that Galen had known everything one needed to know about medicine, just as Aristotle was believed to have known everything about natural philosophy. Galen became regarded as the greatest author-ity in university medicine. Thus Taddeo Alderotti and his pupils in Bologna tried to get a perfect understanding of Galen’s ideas, wrote numerous commentaries on his works and compiled lists of them. They also compared different translations of his works.6 There was a similar level of enthusiasm in Montpellier. In Bernard de Gordon’s works Luke Demaitre has found over 600 references to Galen and his works, twenty-four being named.7 Both Bernard de Gordon and Pietro Torrigiano called Galen the “prince of medicine.”8

As a result, more and more of Galen’s texts were included in the curriculum of the universities. The statutes of the University of Montpellier in 1309 mentioned as many as seven of Galen’s treatises,9 and there can be no doubt that Galenic works in medical instruction were also introduced in other universities, although official lists of books included in the curriculum were often constructed much later, for example in 1405 in Bologna. Thus Galen’s works, although they were already known in the learned medical world of the Middle Ages, began to make an increasingly important impact from the 1270s and 1280s onwards. As a result, an intellectual movement emerged, referred to as “New Galen” by many historians of medicine.10

Michael McVaugh argues that this knowledge of New Galen brought dramatic change to the intellectual world of scholastic physicians.11 These “new” texts gave a fresh insight into the concepts of health and disease, and thus had an impact on the scholastic analysis of melancholy. The most important feature of the New Galen was the theory of complexion (complexio). Complexio was a Latin translation of Galen’s term krasis, literally a mixture.12 Later in the Middle Ages krasis was often translated as temperament, based on the Latin word tempero. By complexion scholastic physicians understood the relationship between the primary qualities hot, cold, wet and dry in the body. These medical primary qualities were derived from Aristotelian natural philosophy, in which they were divided into active (hot and cold) and passive (moist and dry). They were understood as forces affecting everything in the sublunar world. Men, animals and plants as well as inanimate nature were composed of the elements earth, water, air and fire, and each element had certain characteristics associated with a pair of primary qualities. Water, for example, was cold and wet. When elements were mixed together they were changed into a new substance, but their dynamic powers, the primary qualities, prevailed. This mixture of qualities, which was the result of the mixture of elements, was called complexion.13 As explained by Bernard de Gordon and others, complexion was therefore a result of the interaction of active and pas-sive primary qualities.14

In Galenic medicine the human being consisted of many complexions. So called homogeneous parts, such as bone, flesh, humour or sinew, had a typical complexion of their own. This was also true of heterogeneous parts such as the head, arm, heart or liver, which were all composed of homogeneous parts. The whole body also had its complexion. Based on Galen’s De complexionibus, scholastic physicians divided complexions into nine categories, one well balanced complexion and eight derivations from that. In the well balanced complexion all primary qualities were equally distributed and intensified. This was usually seen as an ideal case, impossible to find in nature. Eight other complexions were either simple or compound, which means that complexion was governed either by one primary quality or by a pair of primary qualities, one active and one passive.

It is important to note that each different part of the body was considered to have its own ideal complexion, this being dependent on the function of the part. Thus the coldness of the brain was appropriate for the mental functions and the heat of the liver was the best for digestion. An equality of primary qualities, that is, an equal intensity of each primary quality in complexion, was not always the best possible alternative. In principle, complexion was in balance when it produced appropriate and the best possible functions. Pietro Torrigiano, for instance, thought that the balance between primary qualities in the brain was excellent when it produced the best possible brain functions, not when primary qualities were absolutely equal.15

It is obvious that Pietro Torrigiano was not prepared to accept a straightforward association between health and good complexion. In his view, good health required equality between homogenous and heterogeneous parts, but also good composition and efficient functioning of different parts of the body in addition to good complexion.16 Effective functions depended on the body having a good composition.17 Thus, there was a certain formula for good health: good complexion followed by good composition and resulting in good effective functions. Taddeo Alderotti argued that the ultimate purpose of complex-ion was to function as “an instrument of operations.”18 So the New Galen made complexion the core of the concept of health. This is implied by Roger French, who stated, with a little exaggeration, that “Health was balanced complexion, illness an unbalanced complexion and therapy was a restoration of complexion.”19 However, Alderotti and Torrigiano, for instance, were not as enthusiastic about the matter.

Melancholy as a Mental Disorder

In Greek “melancholy” was a word for black bile, an association familiar to scholastic physicians and much used by them. Black bile was one of the bodily humours, the others being blood, yellow bile and phlegm. Humours were created in the liver from compacted food and they passed into the rest of the body via the veins. Their function was to nourish the body and maintain its complexional balance. Overabundance, lack of or corruption of any humour resulted in changes in health and possibly caused the body to deteriorate, causing illness. Too much black bile resulted in health problems and illnesses, but at the same time it is worth remembering that a certain quantity of black bile was a necessity. Its special function, together with yellow bile, was to purify and fortify the blood.20

The term melancholy was also used to refer to a mental condition, and this is what the term can be taken to mean hereafter in this chapter. It was a potential or actual psychic disorder caused by a humoral imbalance in the brain, which in turn resulted from an excess of black bile. Excesses of any of the other humours in the brain also resulted in mental disorders; frenzy, lethargy and mania being the consequences of excess blood, phlegm or yellow bile, respectively. Mental disorders were therefore explained by physiological means in Galenic medicine.

According to Galen, melancholy referred either to a complexion that predisposed a person to different forms of mental disturbances or to a non-febrile but chronic mental condition.21 In scholastic medicine the latter case was most often alluded to. For example, when Bernard de Gordon analysed the question of melancholy in his famous Lilium medicinae, he defined it as a corruption of the soul without the fever.22 It is important to note that the soul in medical tradition was not the same as the Christian immortal soul. In this matter scholastic physicians followed Galen, who had derived his theory from Plato. The soul was divided into three powers, associated with the three main organs of the body, the liver, the heart and the brain. Soul made the physiological systems connected with these three main organs work properly.23 When he referred to the soul Gordon undoubtedly meant the powers of the brain. What corrupted the mind was, of course, black bile. It “clouded the soul” and disturbed the work of animal spirits.24 Normally “bright and luminous” animal spirits were the mediators which activated the functions governed by the brain, that is, intellectual activity, sense perception and voluntary motion. Thus, if their work was disturbed, various problems with these functions would follow. In Bernard de Gordon’s view, imagination, ratio and memory were shaken.

The principal source of problems was that when there was too much black bile, which was cold and dry in complexion, the normal complexion of the brain, which was cold and moist, was altered.25 The impact of complexion theory is clear in this assumed process. The brain functioned best when it was cold and moist, as it properly should be. It was this balance that was disturbed by too much black bile.

Melancholy was identifiable through many signs. In the Hippocratic Aphorisms it was stated that melancholy humour was likely to be followed by apoplexy of the whole body, convulsions, madness or blindness. Other signs mentioned were prolonged fear and depression.26 The complexity of the concept of melancholy is thus already apparent in Hippocratic theory. Galen enumerated fear, anxiety, sadness and misanthropy and he also insisted that fear and despondency were exhibited in all melancholic patients. Moreover, melancholic persons often feared death.27

Scholastic physicians specified various signs of melancholy, such as laughing excessively, weeping, inclination to commit suicide, fearing the fall of heaven or fear of being swallowed by the earth. Melancholy could also bring on visual hallucinations, delusions of being somebody else, perhaps a king, an animal (often a cockerel), or a demon. A melancholic might also believe that he was able to predict the coming of the Antichrist. However, in Bernard de Gordon’s view the common feature was hatred of life itself and continuous sorrow.28 In addition, melancholy was often exhibited in various compulsive movements.29

The variety of melancholic subspecies thus covered a wide range of illnesses from severe psychoses to mild depression. Moreover, in the Aristotelian Problemata XXX melancholy was associated with “divine frenzy,” thus creating a long tradition in western culture, which linked melancholy with philosophical and artistic minds. This work, possibly written by Aristotle’s student Theophrastus, was translated into Latin by Bartolomeo da Messina only in the mid-thirteenth century.30 Perhaps because of this, the Aristotelian perspective appears not to have been an issue for the scholastic physicians discussed here.

There were plenty of reasons why black bile might increase or become corrupted. In Bernard de Gordon’s view, the emotions fear, sorrow and worry were particularly liable to increase the quantity of black bile. Some foodstuffs might also have the same effect, for example beans, old cheeses and meat of rare for-est animals.31 On the other hand, black bile could be corrupted as a consequence of digestion problems, bad hygiene or trying to restrain one’s evacuation movements.32

Bernard de Gordon also paid attention to a special form of melancholy, love-sickness.33 This illness had already been mentioned in the Hippocratic corpus, but only in medieval Arab culture had it been synthesised into a theoretical framework. An especially important text was Viaticum peregrinantis, written by the Arab physician Al-Jazzar in the tenth century and translated, or paraphrased, into Latin by Constantine the African in the late eleventh century. One chapter of this book, which was intended for travellers, analysed passionate love. It was described as an extreme form of pleasure or “a disease touching the brain.”34 Gordon’s analysis of this special form of melancholy was based on Viaticum, related to Galen’s ideas, and he also used Ovidius’ poems to make his points clearer. Bernard de Gordon thought that the cause of lovesickness was basically a corruption of the estimative power of the soul. As a consequence of this a woman would appear to a patient to be more pleasant, beautiful, venerable, moral and of better nature than any other woman. In Bernard de Gordon’s view, lovesickness was more common in men than in women because the former were hotter in complexion. However, it was possible for women to suffer from it as well.35 As the disease developed the patient’s ability to make rational judgements was corrupted and he could not think of anything else but his love. Because this would be continuous, it was called sorrowful melancholy.36 A man suffering this disease did not sleep, eat or drink well, and consequently suffered a progressive loss of strength. If a patient heard songs about lovers separated from one another, he began to sing and laugh himself. Moreover, if the name of the loved one was mentioned, the pulse of the patient became irregular and quickened.37

Melancholy affected the body physiologically as well as mentally. The basis of this belief was that melancholy was strongly connected with the emotions, as noted above, and the emotions had an influence on the innate heat (calor innatus) and vital spirit (spiritus vitalis). In Galen’s medicine, innate heat originated in the heart and was distributed around the body via the arteries. It kept the body warm and thus made the other bodily processes possible. For this reason it was often associated with life itself. It also had an effect on digestion, distribution of the food and the birth of the humours, besides controlling motion and sensation indirectly.38 Vital spirits activated the organs and functions governed by the heart.

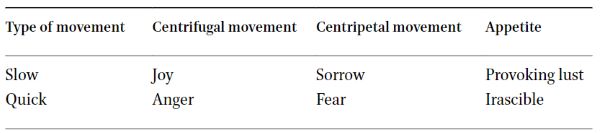

Scholastic physicians usually considered four emotions, joy, anger, fear, and sorrow, which they thought were the basic ones. However, they often alluded also to anxiety and shame, which were kinds of composites of basic emotions.39 Physicians referred to emotions as accidents of the soul (accidentia animae), because emotions could move innate heat and spirits, either from the heart to the extreme parts of the body (centrifugal) or vice versa (centripetal). These movements had physiological consequences in the body, and they could be either slow or quick. Slow motions were associated with the provoking lust and quick motions with the irascible parts of the appetitive soul.40 The four basic emotions can be classified as shown in table 1.

In the melancholic disposition the most significant emotion was undoubtedly sorrow, although signs described above also alluded to fear. Sorrow moved innate heat and vital spirits slowly from the extremes of the body toward the heart. It is important that melancholy did not have immediate effects but was a developing process. The centripetal movement was manifested in symptoms such as paleness of the skin and coldness of the extremities. Arnau de Villanova, Bernard de Gordon’s colleague at the University of Montpellier in the 1290s, argued that sorrow cooled and dried all parts of the body, which led to “internal decay and exhaustion.”41 Consequently rationality, memory, judgement and the functions of the senses were disturbed.42 Pietro Torrigiano concurred on the cooling and drying effects of sorrow, emphasising the effect this had on the brain. He also noted that immense sorrow might even suffocate the innate heat.43

Born Melancholic

As noted earlier, Galen maintained that melancholy could be understood as a complexion predisposing a person to different forms of mental disturbances. His thought was thus founded on the complexion theory, especially where it concerned the complexion of the whole body. It was thought that every person had one of the eight unbalanced complexions at birth, excluding the well balanced complexion which was regarded as an impossibility. However, often only four compound complexions, governed by two primary qualities, were analysed, because it was believed that a complexion governed by only one primary quality would quickly lose its balance, thus ensuring that the simple complexion would become a compound complexion sooner or later. These four principal types of complexion were governed by hot and moist, hot and dry, cold and dry, and cold and moist respectively. According to the complexion theory, a person could be born as cold and dry, which meant he or she was a melancholic. A hot and moist person was sanguine, a hot and dry person choleric, and a cold and moist person phlegmatic. In the earlier medieval tradition melancholic, sanguine, choleric and phlegmatic were combined with the bodily humours black bile, blood, bile and phlegm respec-tively, but in the light of New Galen humours were also subordinated to primary qualities.

Using Avicenna’s vocabulary, the complexion of birth was called innate complexion (complexio innata) and it was believed to prevail throughout the person’s life. It was introduced to the body through the “principles of birth,” that is, semen and menstrual blood. In addition, the position of the stars during the conception was thought to have an influence on the future complexion of a child. If Saturn was the governing planet during the conception the probability that the child would become a melancholic was greater. Saturn had a cold and dry complexion and was, moreover, contrary to life and malevolent.44

The Florentine Pietro Torrigiano located complexion theory within the larger theoretical framework of bodily dispositions and states. He created his model by examining the bodily system introduced in Galen’s Tegni, where Galen argued that medicine concerned healthy, morbid and neutral bodies, their signs and causes. Bodies were also distinguished according to whether simpliciter (simply, plainly) or vt nunc (now, at present, in these circumstances) was appropriate to their behaviour. Furthermore, Galen introduced the idea of the latitude of health, using the same vocabulary as in defining medicine. These apparent contradictions were explained, sometimes painstakingly, by scholars, but Pietro Torrigiano’s interpretation was perhaps the most coherent and most frequently discussed after his death.45

On the basis of Aristotle’s Categories, he argued that simpliciter was akin to “absolutely,” and referred to something that existed beyond the limits of any specified time period,46 and independently of circumstances at any given time.47 It was hard to change or remove, because it was an inherent natural characteristic of a human being.48 By contrast, vt nunc was subject to the state of affairs at a given time and changed easily.49 According to Pietro Torrigiano, every human being naturally had some healthy characteristics, inclinations, which were totally or largely unmovable. These permanent characteristics should be distinguished from the unstable bodily conditions a man experienced during his lifetime.

This distinction was very important, both theoretically and practically. It was necessary for a physician to know his patient’s permanent state, because only then would his actions be rational. It was very important to know, for example, whether a man had had a tendency to get a cough more or less regularly since his birth, or an inclination to feel bad in winter and well in summer. This knowledge was to be found in the innate complexion of a man, referring to the natural state of each man. In Pietro Torrigiano’s view, a natural state was always a healthy one.50 A melancholy person had a health specific to him- or herself. All these complexional states belonged to the latitude of health, which encompassed a wide variation in possibilities.

It should, however, be kept in mind that the innate complexion and the natural healthy constitution that resulted from it did not mean that a person was always healthy. Accidentally, or because of his or her inclination, he/she might sooner or later become ill.

Pietro Torrigiano thus formulated theoretically what was already a common view in thirteenth-century medical practice, the characterisation of various complexions by their mental and physical symptoms. The innate complexion determined a person’s character and outlook, and accordingly what kinds of diseases he or she would probably have during his or her lifetime. Innate complexion thus defined the type that a person was.

Already in the Salernitan regimen, probably not composed until the latter part of the thirteenth century, the melancholic person was regularly described in both physical and mental terms. The verse goes as follows:

There remains the sad substance of the black melancholic temperament, Which makes men wicked, gloomy, and taciturn. These men are given to studies, and little sleep. They work persistently toward a goal; they are insecure. They are envious, sad, avaricious, tight-fisted, Capable of deceit, timid, and of muddy complexion.51

Bernard de Gordon argued that a melancholic had a tendency to succumb to cold and dry diseases. These kinds of diseases lasted a long time and were often chronic.52 This did not mean that a melancholic could not have other kinds of diseases, only that he was disposed to have certain kinds.

To be melancholic by nature also meant a tendency to feel emotions like sadness and fear. Moreover, even if two people felt the same emotion, this could have a totally different impact if they had different innate complexions. Taddeo Alderotti argued that if a melancholic had great sorrow, he might die, but if the same kind of sorrow occurred in a choleric he would become furious.53

Growing Up Melancholic

In another consilia Taddeo Alderotti gave advice to a choleric person who was turning melancholic as he aged.54 This example illustrates that although the state of melancholy might exist from birth and last a lifetime, it might also simply be a temporary disposition. Ageing was one of the many things that might bring on melancholy.

In medieval medicine old age was systematically defined as cold and dry, an identification that had already been made in Aristotelian and Galenic texts. Life was a process during which a hot and moist child progressively became a cold and dry old man or woman. This process was determined by the interaction of life-giving innate heat and its original fuel, which was most often called radical moisture, but also known as substantial, natural, seminal or innate moisture. The idea of radical moisture originated with Ionian natural philosophers, was developed by Aristotle and put into a medical context by Galen.55 According to Galen, life and health depended on the balance between innate heat and radical moisture.56

Ageing was explained with the concepts of innate heat and radical moisture. Taddeo Alderotti analysed the question in his commentary on Joannitius’ Isagoge. In his view, successive stages of life occurred according to the relation between innate heat and radical moisture in the body. In youth there was so much radical moisture in the body that it was able to provide both innate heat and the growth of the body parts. For this reason the complexion of youth was hot and moist. In adulthood moisture maintained innate heat and was able to keep the constitution intact. This period of life was hot and dry. But in old age the balance between innate heat and radical moisture changed and the latter was no longer sufficient to conserve innate heat at the same level as it had earlier. As a consequence innate heat diminished.57 Ageing meant that both innate heat and radical moisture were steadily decreasing. According to Taddeo Alderotti, when innate heat consumed radical moisture the latter naturally diminished and because it could not provide so much fuel to the innate heat, which therefore grew weaker as well. The body was “in a continual state of deterioration.”58 It followed that the body became ever more cold and dry.

The changes in balance between innate heat and radical moisture also pro-duced complexional changes in the body. Taddeo Alderotti, like most scholastic physicians, believed that there were four ages in the life of man: hot and moist youth, followed by hot and dry adulthood, leading to cold and dry old age and ending in cold and moist senility.59 The last age was, however, only accidentally moist; the moisture was a waste product, of no use to the body. According to Taddeo Alderotti, the transition from one age to another had taken place when powers and faculties were manifestly changed.60 Pietro Torrigiano agreed with his master, insisting that complexional changes in the body made it reasonable to presume that a person had moved on to the next age.61 Physiological processes determined the age, not the calendar.62 However, in Arab medical literature ages were defined more precisely: youth ended when a person was 25–30 years old, adulthood when 35–40, and old age when 55–60; for senility there was no defined end.63

There was, of course, an obvious problem with the above theory. How was it possible that complexion changed when a man grew older, if he had been born with some particular innate complexion? This question was taken up by Pietro Torrigiano. In his view, the innate complexion should be understood by the proportions of its components relative to age: the ratio of any two relative to each other remained constant, even when the absolute levels of each fell as old age began. When a hot and dry choleric turned cooler and drier because of ageing, he/she remained as choleric as before by comparison with other inner complexions in people during the same age. In absolute terms his or her hotness and dryness were not maintained at the same level, but when compared to sanguine, melancholic and phlegmatic men of the same age he or she was still hot and dry.64

Generally, when someone aged he or she became ever more cold and dry, and as a consequence ever more susceptible to melancholic diseases. A person also became more prone to sadness and other emotions typical of a melancholic as he or she grew older.

Taking Care of a Melancholic

Scholastic physicians were keen to classify the various tasks of the physician. There were four main tasks: to conserve health, to preserve health, to restore health, and to cure illness. Taking care of one’s current health was the object of conserving health. However, there was always a danger that the balance of health would be lost, so it had to be defended and thus preserved. Nevertheless, changes in health were inevitable, and then the balance was to be restored.65 Lastly, if a person became ill, the body had to be cured. In all that he did, a physician had to take into account the innate complexion of his patient, the environment in which his patient lived, the season, the stage of life (“age”) he was in, and the actual condition of health he had. Taddeo Alderotti argued that these features might make it impossible to order what should theoretically have been the best regimen for that illness, because of complications caused by the interplay of the above factors.66

A scholastic physician had three methods of healing: dietetics, medicinal potions and surgery. Avicenna called them the instruments of medicine.67 Dietetics was used in maintaining health, including conserving, preserving, and restoring health, and in curing illness. Dietetics usually consisted of six elements, the called non-naturals: air, food and drink, sleeping and waking, motion and quiet, evacuation and repletion, and the accidents of mind. These were environmental, physiological and psychological factors that necessarily affected the body, either bringing health or causing illness. By contrast with dietetics, potion and surgery were more or less reserved for healing.

What of the regimen for melancholic patients? To answer this question, an examination of Bernard de Gordon’s regimen in Lilium medicinae and Taddeo Alderotti’s two consilia (referred to above) is necessary.

As a general regimen against melancholy Bernard de Gordon recommended joy and laughter, which counteracted grief and the sorrow of melancholy. Bernard de Gordon also indicated that the house of a melancholic should be clean (clarus), luminous and full of pleasant odours. Everything at home should be pleasant and delightful, and everything that might cause fear should be avoided. Music and discussions with friends were both beneficial.68 Bernard de Gordon, therefore, placed a heavy emphasis on the regimen of the mind, which if carried through would also help with physiological problems regarding innate heat and radical moisture. Another important aspect of Bernard de Gordon’s regimen was based on the principle that opposites are cured by opposites (contraria contrariis curantur). Hence cold and dry melancholy could be healed by a moisturizing regimen. In Gordon’s view a convenient regimen was therefore sleep, rest, leisure, a bath before a meal and proper nutriment. Good diet included chicken, lamb and clear wine, for example.69

In the case of lovesickness Bernard de Gordon also gave attention to the regimen of the soul. If the patient could still accept rational advice, he should be persuaded by talking. But if this was not the case, then a better method of healing was the lash. Otherwise a regimen of being with friends, strolling around springs and groves, looking at beautiful views and listening to songs and music was effective.70 The mind could also be shocked back to normality. In Bernard de Gordon’s view, the last hope was to collect the menstrual blood of the loved woman, make the youngster smell it or stare at it and say to the patient: “this is what your love is like.” If this did not work, then the physician’s efforts were in vain; lovesickness was a devil’s plot.71

Taddeo Alderotti was very systematic in his advice to Marquise Obizzo d’Este, referring to all six non-natural things, potion and surgery as components of the cure for his melancholy. Regarding non-naturals Taddeo Alderotti believed that contraria contrariis curantur. A melancholic suffering insomnia should stay in moist air.72 His food should be well salted and his wine clear, aromatic and usually white. Impurities had to be filtered off from the wine. Taddeo Alderotti recommended venison, but not beef or the meat of bear, wolf or deer. The eating of cheese and milk was also forbidden, but both sea and freshwater fish could be eaten. Taddeo Alderotti similarly divided leguminous plants, fruits and spices, into permitted and forbidden for the Marquess’ table. Overeating was strictly forbidden, the Marquess being advised to eat according to his own natural appetite. The meal should begin with the food that was digested most easily. In wintertime hot nutriment was recommended and in summer cold.73 These recommendations for consumption of food and drink were quite common and could be used as general advice. The condemnation of overeating and use of seasonal diet variations were already common in medical literature by the late thirteenth century, when Taddeo Alderotti was writing his consilia.

Taddeo Alderotti argued that exercise should not be practised before a meal, but after it, so a light walk was allowed until the food had settled at the bottom of the stomach. After that rest was the only correct course.74 These ideas underlined the significance of proper digestion, which occurred in three phrases according to scholastic physicians, the first in the stomach, the second in the liver and third in the veins and in the limbs, where the food was assimilated to the body. Taddeo Alderotti undoubtedly thought that the walking should be over and the rest begun before the first phase of digestion had been completed. As well as digestive remedies the use of purgatives was recommended. It was believed that not all waste products after digestion (excreta) were expelled from the body via normal channels. Among other modes of exercise Taddeo Alderotti advocated massage, after which the Marquess should take a bath, both useful for removing waste. As regards mental health, Taddeo Alderotti agreed with Bernard de Gordon in thinking that laughter, looking at beautiful and pleasant things, and listening to calming songs and music made the mind joyful in the best possible manner.75

The most interesting non-natural in the case of the Marquess was obviously the problem of sleep and wakefulness. Taddeo Alderotti suggested various things that could cause drowsiness, for example, aromatic red wine, pork, peanuts or milky poppy. The striking point is that non-natural thing sleep and wakefulness had no special place in Taddeo Alderotti’s advice. However, this is accordance with the general idea of dietetics, which was fundamentally based on general regulation of life. The Marquess had to change his whole lifestyle, or most of it, to get rid of his melancholy. Healing with the help of non-naturals was a comprehensive process.

Taddeo Alderotti referred to medicines in addition to non-naturals. He mentioned many, beginning with the all-purpose medieval miracle medicine tyriaca, which was prepared from many ingredients, but almost always included the flesh of a poisonous snake. Every physician had a recipe of his own for tyriaca. This potion was commonly used to counter an overabundance of the melancholic humour, black bile.76

Surgical regimens included cauterization and trepanation. The branding iron had to be put on the skin over the spleen, where black bile was believed to be stored. Alderotti probably based his advice on the surgical manual of Arab Muslim physician Albucasis (about 936–1013), which included a detailed description of cauterization.77 Trepanation was known already in ancient Egypt and was alluded to in many antique texts. Alderotti’s argument for its use against melancholy was taken from Italian surgeon Ruggero di Salerno’s early thirteenth-century suggestion.78 According to Taddeo Alderotti, the surgeon should first bore a hole in the anterior lobe of the skull, and then moisten the dry material of the brain with olive oil.79

It is interesting that Taddeo Alderotti’s recommendations for the Marquess did not include venesection, which was frequently recommended by him for other cases and often used in cases of melancholy. The blood was drawn from the frontal of the head.80 Taddeo Alderotti may have thought that bloodletting would weaken the Marquess too much and thus be dangerous to him, which was the reason why old people, infants and pregnant women were not usually bled. More probable, however, is that Taddeo Alderotti followed Galen’s lead. Galen had insisted that bloodletting should be done only in those cases in which melancholy had arisen from the excess of black bile in the blood. In these cases the overabundance concerned the whole body, not only the brain. If the condition had arisen in the brain itself, a patient was not to be bled. One symptom of the melancholy created only in the brain was in Galen’s view sleeplessness, which demonstrates that Taddeo Alderotti’s decision had a Galenic basis.81

Taddeo Alderotti’s regimen for the melancholic Marquess was, in fact, very unspecific. Even less specific, if anything, was his advice to the patient turning melancholic because of ageing. Regarding the element of air, Taddeo Alderotti discussed the right place for the windows of the house the patient lived in. As usual, he recommended the positioning of the windows to face east and north, so that the rays of the morning sun would cleanse the rooms. The rooms were supposed to be filled with fine scents by making use of flowers, herbs, aloes, and myrrh. In wintertime the fires should be kept burning in the fire-places. In the section on food and drink Taddeo Alderotti again introduced plenty of foodstuffs and warned not to eat too much. Moreover, the sufferer should not eat until he was hungry. Again the foods that were easily digestible had to be eaten first. After eating the patient must not exercise, but was permitted a light walk. Otherwise Taddeo Alderotti recommended both massage and baths.

Regarding sleep and waking, Taddeo Alderotti was very specific, indicating the right time to go to bed, the duration of sleep and the position in which to sleep. One should not go to bed straight after dinner, nor much later, because second and third digestion functioned better while sleeping. Sleeping should take place at night, not in daylight. In the winter the patient had to sleep longer than in the summer. The best position to adopt was first on the right side, then on the left side and lastly on the right side again.82 All this advice was often repeated in late thirteenth- and fourteenth-century health advice books and other regimens.

Regarding the accidents of the soul, all excess of worry, hate, sorrow or fear had to be avoided and joy and laughter sought instead. Joy must not be sought for by having coitus too often, but when that did take place it should be at night just before going to sleep. If coitus made a man weak, he should take a strengthening medicine afterwards. Moreover, the body should be purified by purging its waste products twice a year, in spring and autumn; if these purges were not enough, and only then, bloodletting should be resorted to.83

What was most important in the regimen described above? The most striking point is the emphasis on emotions as a very important factor in taking care of a melancholic, whatever the reason for the melancholy. Another important aspect is the effort to change the patient’s lifestyle, which was a tendency in scholastic medicine in general. The holistic view of the human being is also obvious: soul and body formed a coherent whole. Regarding the types of regimen, the dictum “opposite cures the opposite” (contraria contrariis curantur) is common to many of them: cold and dry melancholy needs a hot and moist regimen. In principle the case of a choleric declining into melancholy as a result of ageing made a difference. In his commentary on Tegni, Taddeo Alderotti posited that the inner change of the body should be fought with the principle “opposite cures the opposite,”84 but at the same time it was necessary to maintain the innate complexion using the like is cured by like – principle. He explained this necessity by giving close attention to the digestion. Because the food was assimilated into the body, the best food was that which had the same primary qualities as the body itself.85 In his practical consilia, however, Taddeo Alderotti does not seem to make use of this refinement, but follows more standard lines.

The lack of religious and magical means of healing is quite striking in scholastic physicians’ advice for melancholic patients. In general it was very com-mon to pray to God or the saints to obtain a cure, or carry amulets or draw magical figures to prevent illnesses or to get rid of them. University educated physicians, however, did not usually pay any attention to these kinds of healing methods – or at least they did not write of them.

There were at least two reasons for this neglect. First, university-trained physicians based their demand for control on medicine on their rational analysis of health and illness. Allowing a place for those healing methods that could not be explained rationally might be dangerous for their business. For example, if the nature of the illness was cold and wet, as in a cough, the rational treatment was based on warm and dry medicine. However, they did not directly deny the possibility of divine intervention and the efficacy of religious healing, which, in the medieval context, was undoubtedly wise enough. Sometimes, in difficult or impossible cases, physicians argued that only God could help the patient. Bernard de Gordon advised a patient suffering from insomnia, after trying every possible medical medium, to repeat the words “horas dominicas.” According to Bernard de Gordon the method worked and the patient slept.86

Secondly, physicians based their science especially on Hippocratic and Galenic texts which explicitly excluded religious and supernatural elements from medicine. Magical healing, like the use of magic stones or figures, was not often mentioned in their writings, since magical healing could not be explained by the theoretical apparatus of rational medicine. Nevertheless, some physicians speculated, for example, about the possibility of transforming the healing power of the stars to the patients with the use of various magical methods.

Conclusion

The signs, causes, and physiological consequences of melancholy implied it was seen as some sort of illness. This was not, however, always the case. In the scholastic medical context, melancholy cannot simply be defined as an illness. It could also be a natural condition of man, derived from birth, or occur because of ageing. In both cases it was linked to health and it always had both mental and physical aspects. This is in accordance with the holistic concept of health derived from antiquity.

The difficulty of defining a person’s condition is clear in scholastic analyses of melancholy. When a person was ill and when healthy was often difficult to determine. Scholars were sensitive to this and noticed the differences between severe cases of melancholy and those that could not be diagnosed as illness at all. Healthy and unhealthy conditions of melancholy were conceptualized within the system of bodily states and dispositions presented by Galen in his Tegni.

The point of view of the scholastic physicians was psychosomatic, and it is striking that they take so little note of theological or moral considerations. For them melancholy was not linked with possession by demons, as laymen sometimes believed,87 but to the physiological processes of the body and to the emotions. This underlines the tendency in scholastic medicine to define all bodily conditions principally in materialistic terms.

Melancholy was often alluded to in scholastic medicine, but this does not imply that it was a common problem. Scholastic, university educated physicians were a marginal group, even within the field of health care, and so were their patients. Physicians normally worked in bigger cities or as personal physicians of popes, bishops, kings and other members of the nobility. Melancholy was often associated with literary work. Besides, Galen and other authorities had written a lot about it, so it had to be taken seriously by scholastic physicians.

Finally, it is worth asking whether Obizzo d’Este followed the advice given by Taddeo Alderotti. Unfortunately, we can only speculate on that. It is certain that there was a demand for rationally founded explanations of disease and regimen among the elite at the end of the thirteenth century. It is therefore possible that Obizzo read Taddeo Alderotti’s regimen, and perhaps he also followed some of the advice given, for example on diet, but he certainly did not undergo trepanation or other forms of medical acre involving surgery. Nor did he die of melancholy, as it is said that he was murdered by his son and successor Azzo d’Este.

Endnotes

- Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, trans. Henry Francis Cary (London, Paris, Melbourne: Cassell & Company, 1892), Canto XII.

- Taddeo Alderotti, Consilia, ed. Piero P. Giorgi and Gian Franco Pasini (Bologna: Università di Bologna, 1997), Consilia XXII, 176: “Egritudo domini marchioris est melancholia cum tanta vigiliarum instantia, quod iam sunt duo anni quod non dormivit aliquid.”

- It was known as Plusquam commentum in artem parvam Galeni.

- Roger French, Medicine before Science. The Rational and Learned Doctor from the Middle Ages to the Enlightenment (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), passim.

- Nancy G. Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine. An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1990), 178.

- Nancy G. Siraisi, Taddeo Alderotti and His Pupils. Two Generations of Italian Medical Learning (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1981), 100–103.

- Luke Demaitre, Doctor Bernard de Gordon – Professor and Practitioner (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1980), 114, table 4.

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae (Frankfurt: Apud Lucam Iennis, 1607), fol. 64r, passim; Pietro Torrigiano, Plusquam commentum in artem parvam Galeni (Venice: Apud Iuntas, 1557), passim.

- They were Tegni, De complexionibus, De malitia complexionis diverse, De simplici medicina, De morbo et accidenti, De crisis et creticis diebus and De ingenio sanitatis. Probably the curriculum also included Galen’s commentaries on the three Hippocratic treatises (Aphorisms, Prognostics and The Acute Diseases). Cornelius O’Boyle, The Art of Medicine. Medical Teaching at the University of Paris (Leiden: Brill, 1998), 148–149.

- See, for example, Luis García-Ballester, “The New Galen: A Challenge to Latin Galenism in Thirteenth Century” in Text and Tradition: Studies in Ancient Medicine and its Transmission Presented to Jutta Kollesch, ed. Klaus-Dietrich Fischer, Diethard Nickel and Paul Potter (Leiden: Brill, 1998), 55–83; Siraisi, Taddeo Alderotti and His Pupils, 101.

- Michael McVaugh, “The Nature and Limits of Medical Certitude at Early Fourteenth-Century Montpellier,” Osiris 2nd series 6 (1990): 62–84, esp. 66.

- Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine, 100. Pietro Torrigiano knew the Greek term. Pietro Torrigiano, Plusquam commentum, I, fol. 13rd: “Crasis vero idem valet, quod complexio.”

- Scholastic physicians were very careful to separate the mixture of elements from the mixture of primary qualities for precisely this reason. See Pietro Torrigiano, Plusqua commentum, I, fol. 13ve: “Nam, sicut mistio est corporum, sic complexio est qualitatum…”

- Bernard de Gordon, De prognosticis (Frankfurt: Apud Lucam Iennis, 1607), 933: “Qualitas igitur, quae resultat ex proportione actiuarum et passiuarum, nominatur complexio.”

- Pietro Torrigiano, Plusquam commentum, II, fol. 47rd: “Cum autem dicitur cerebrum tem-peratum, intelligendum est temperamento a iustitia, scilicet quod caliditas, frigiditas, humiditas, et siccitas sunt in ipso non pariter, sed secundum mensuram proportionis ipsorum ad opus cerebri, ad quod impariter ordinantur.”

- Pietro Torrigiano, Plusquam commentum, I, fol. 15rb: “Est igitur simpliciter sanum corpus id quod est ex generatione coaequale in simplicibus membris et coaequale in compositis; haec enim duplex coequalitas est vna sanitas eius; nec complexio est sanitas, sed coae-qualitas in ea, non quidem absolute, sed ad opus.”

- Pietro Torrigiano, Plusquam commentum, I, fol. 15a–b: “Post haec autem dicemus, quod aequalitas compositionis organorum non intelligitur absolute, sicut ne coaequalitas in complexione simplicium, sed ad aliud dicitur, sicut illa, scilicet ad complementum operis ipsorum. Est autem coaequalitas in compositione organorum penes quatuor naturas, quibus indigent ad perfectionem sui operis (sicut Galenus monstrat prima particula de morbis et accidentibus) que sunt forma, quantitas, numerus, positio. Et forma est vna quinque rerum, scilicet figura, concauitas, porus, lenitas, et asperitas: per positionem autem ingelligitur locus et societas: per numerum autem numerus consimilium in com-posito, aut numerus compositorum in compositio ipso, sicut digitorum in manu.”

- Taddeo Alderotti, In Isagogas Joannitianas Expositio (Venice: Apud Iuntas, 1527), 346r: “Nam complexio est instrumentum operationis.”

- French, Medicine Before Science, 101.

- Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine, 106.

- Galen, De locis affectis, trans. R. Siegel (Basel, New York: Karger, 1976), III, 10.

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.19.246: “Mania et melancholia sunt corruptiones anima sine febre.”

- Michael W. Dols, “Galen and Islamic Psychiatry,” in Le opere psicologiche di Galen, ed. Paola Manuli & Mario Vegetti (Naples: Bibliopolis, 1988), 243–280, esp. 247.

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.19.246: “Humor enim melancholicus inficiens cerebrum, perturbans spiritus et obnubilans, animamque obfuscans est causa corruptio-nis mentis.”

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.19. 246: “Cum enim complexio cerebri, quae natu-raliter est frigida et humida, est sicut oportet, et spiritus sunt clari et luminosi, accipit bona imaginatio, cogitatio et memoria, et tempore somni et tempore vigiliarum: sic quando praeter naturam ista sunt, accidunt corruptiones diuersae et in diuersis partibus.”

- Hippocratic Writings, ed. with an introduction G.E.R. Lloyd, trans. J. Chadwick and W.N. Mann (London: Penguin Books, 1978), Aphorisms XXIII, LXVI.

- Galen, De locis affectis, III, 10.

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.19.249: “Signa generalia sunt ista; de proprietate omnium melancholicorum est habere odio istam vitam, fugere focietatem hominum, esse in continua tristitia…”

- Siraisi, Taddeo Alderotti and His Pupils, 232–233.

- On this tradition, see Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy. Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art (London: Nelson, 1964).

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.19.247: “Causae autem antecedentes, sunt omnia illa, quae multiplicat melancholiam, siue per se, siue per accidens, siue per viam adustio-nis et corruptionis. Ista autem sunt multa, scilicet timor, tristitia, solicitudo, et similia. Secunda causa potest esse, omnis ille cibus, qui multiplicat melancholicam, sicut sunt lentes, fabae, et alia legumina, omnia grana minuta, panis oprius, vinum grossum turbi-dum, caseus antiquus, caules, extremitates et palmites arborum stypticarum, carens bouinae, et potissimum antiquae et induratae in sale, carnes leporum, cuniculorum, apris, et carnes omnium animalium syluestrium inusitatorum, et illicitorum, quae come-duntur in quibusdam regionibus. Aut ratione malae consuetudinis, aut ratione famis, sicut sunt vulpes, erici, asini, muli, et similia, de quibus facit mentionem Gal.3.de interiobus.”

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.19. 247: “Tertia causae esse potest humor corruptus, malus, adustus, et ita aduritur…potest esse corruptio digestionis in membris, malitia mundificatinos, et retentio superfluitatum.”

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.20.255: “De amore quid ‘eros’ dicitur…siue amor est sollicitudo melancholia propter mulieris amorem.”

- al-Jazzar, “Viaticum” in Lovesickness in the Middle Ages: The Viaticum and Its Commentaries, trans. Mary Frances Wack (Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania, 1990), 14.

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.20.259: “Quinto ista passio frequentius aduenit viris quam mulieribus, quia viri sunt calidiores, et vniversaliter foeminae frigidiores, quod patet in masculis brutorum qui cum furia et impetu mouentur ad coitum implendum.”

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.20.255–256: “Causa huius passionis est corruptio aestimatiuae, propter formam et figuram forties affixam, vnde cum aliquis philocaptus est in amore alicuis mulieris, ita fortie concipit formam, figuram et modum, quoniam credit et opinatur hanc esse meliorem, pulchriorem et magis venerabilem, magis spe-ciodam, et melius dotatam in naturalibus et moralibus, quam aliquam aliarum, et iedo ardenter concupiscit eam, fineque modo et mensura, opinans si posset finem attingere hanc esse suam felicitatem, et beatitudinem, et intantum corruptum est iudicium ratio-nis, quod continue cogitat de ea, dimittitque omnes suas operationes, it quod si aliquis loquatur cum eo, vix intelligit aliqua alia. Et quia est continua meditatione, ideo sollicitudo melancholica appellatur.”

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.20.256–257.

- Richard J. Durling, “The Innate Heat in Galen,” Medizinhistorisches Journal 23 (1988): 210–212.

- Arnau de Villanova, for example, wrote in his Arnaud de Villanova, Summa medicinalis [about 1495?], tract. 3, cap. 19, 161: “Et quia alteracio ista est sexduplex, prout sunt sex species accidencium animi, que sunt: gaudium, tristicia, timor, ira, verecundia et anguscia.”

- See Pedro Gil-Sotres, “La higiene medieval,” in Arnaldi de Villanova Opera medica omnia X.1: Regimen sanitatis ad regem Aragonum, ed. Luis García-Ballester et Michael McVaugh (Barcelona: Seminarium Historiae Scientiae Barchinone, 1996), 569–861, esp. 816; Simo Knuuttila, Emotions in Ancient and Medieval Philosophy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2004), 212–216.

- Arnau de Villanova, Summa medicinalis, tract. 3, cap. 19, 161: “Tristicia vero que oponitur qaudio corpus mutat opposito modo, non tamen calefacit interiora, sed omnia membra infrigidat et exsiccat et causat consumpcionem corporis et vigilias…”

- Arnaud de Villanova, Regimen sanitatis ad regem Aragorum, in Arnaldi de Villanova Opera medica omnia X.1: Regimen Almarie, ed. Luis García-Ballester et Michael R. McVaugh (Barcelona: Seminarium Historiae Scientiae Barchinone, 1996), 423–470, Cap. VI, 112: “Tristicia vero corpus infrigat et exsiccat…ingenium habetat, apprehensionem impedit, iudicium obscurat et obtuncit memoriam.”

- Pietro Torrigiano, Plusquam commentum, III, fol. 104rc: “Tristitia autem et dolor per oppositum diffinitur, et est principium motus, qui est ad fugam. Propter quod ex perceptione rei inconuenientis et corrumpentis accidit inconueniens et innaturalis motus calori et spiritui, s. qui est ex circumferentia ad centrum: ideoque ex magna tristitia accidit calorem extingui et suffocari ex nimia suis constrictione. Constringuntur autem ab hac fuga caloris et spiritus omnia membra, vt ab humidis et mollibus inter ea, sicut cerebro et oculis, experimatur et mucus, et lachryma: propter quod infrigidat et des-iccat tristitia, sicut gaudium calefacit et humectat.”

- Bernard de Gordon, De prognosticis, 1003: “Saturnus…vitae contrarius, maleuolus, frigidae et siccae complexionis, tardi motus, habens aspectum…”

- See Per-Gunnar Ottosson, Scholastic Medicine and Philosophy (Naples: Bibliopolis, 1984); Timo Joutsivuo, Scholastic Tradition and Humanist Innovation. The Concept of Neutrum in the Renaissance Medicine (Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 1999).

- Pietro Torrigiano, Plusquam commentum, I, fol. 11d–e: “Dicuntur autem dupliciter, nam quodlibet illorum dicitur sanum, et aegrum, et neutrum aut absolute et simpliciter, sine additione alicuius determinantis aut diminuentis conditionis: et hoc intendebat, cum dixit, Hoc quidem simpliciter.” Ibid I, fol. 16c: “Est autem habitus (sicut dicit Philosphus) qualitas difficile mobilis a subiecto, semper vel vt multum comitans.”

- Pietro Torrigiano, Plusquam commentum, I, fol. 11g: “Cum ergo vt nunc determinet rem quae sic dicitur ad tempus presens, tunc simpliciter proprie dicetur priuatione additionis temporis determinati, vt sit dicere simpliciter tale in omni tempore existens tale, vel sine determinatione temprois existens tale, cuius signum est quod diuisum est in semper et multum tale.”

- Pietro Torrigiano, Plusquam commentum, I, fol. 22b: “Medicinae enim non est distinguere nisi corpus naturae, et defectus naturae, sicut supra diximus: sed omne corpus naturae, id est, omne corpus a dispositione sua naturali prima, dicitur simpliciter hoc vel illud.”

- Pietro Torrigiano, Plusquam commentum, I, fol. 16c: “Dispositio vero qualitas de facili mobilis a subiecto, et inde comitans vt nunc tamen.” Ibid I, fol. 11ve: “Aut dicitur vnumquodque sanum, et aegrum, et neutrum non simpliciter, sed secundum additionem conditionis temperis praesentis: et hoc intendebat, cum dixit, Hoc vero vt nunc…” See Aristotle’s ideas in Aristotle, Categories, in The complete Works I–II. The Revised Oxford Translation, ed. J. Barnes (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1984), 8, 8b25–9a6.

- Pietro Torrigiano, Plusquam commentum, I, fol. 16vg.

- Regimen sanitatis salernitanum, A Critical Edition of Le Regime Tresutile et Tresproufitable pour Conserver et Garder la Santé du Corps Humain, trans. Patricia Willet Cummins (Chapel Hill: North Carolina Studies in the Romance Languages and Literatures, 1976), 14. Regimen sanitatis salernitanum was a health advice manual composed from various verses. Its original version was annotated and edited by Arnau de Villanova in Montpellier in the late thirteenth century.

- Bernard de Gordon, De prognosticis, Particula II, Caput IX, 935: “Aegritudines igitur ex cholera et sanguine erunt breues cum terribilibus accidentibus. Aegritudines ex phleg-mate et melancholia erunt longae et malae terminationis sine timore accidentium…”

- Taddeo Alderotti, In Cl. Galeni Micratechnen commentarij [1523], III, Lectio 6, fol. 162v.

- Taddeo Alderotti, Consilia, Consilia CXXII, 326: “De causis preservantibus corpus declinans ad melancolicam complexionem propter fluxum etatis…corpori colerico iam declinanti ad melancholicam complexionem…”

- Thomas S. Hall, “Life, Death and the Radical Moisture. A Study of Thematic Pattern in Medieval Medical Theory.” Clio Medica 6 (1971): 3–26, esp. 6–8.

- Galen, De complexionibus, in Opera Omnia I, ed. C.G. Kühn (Leipzig: Officina Libraria c. Gnoblochii, 1821–1833), 509–694, esp. 521–523.

- Taddeo Alderotti, In Isagogas Joannitianas Expositio (Venice: Apud Iuntas, 1527), 343r–400v, 369r: “Ad hoc dico quod etas sequitur nexum et vnionem caloris naturalis cum humido radicali. Nam donec humidum radicale talem habet proportionem cum calore radicali (sic) quod ipsa humiditas non solum custodit calorem sed etiam membris prebet augmentum tunc durat adolescentia et tunc complexio calido et humido. Quoniam questo talem habet proportionem quod humidum solum potest conseruare ipsum calo-rem et corpus in eodem statu tenere tunc est iuuentus…calor talem habet proportionem ad humida quod hoc non potest conseruare calorem imo diminuitur tunc distingue. Nam aut est tanta diminutio quod parit propter indigestionem humiditatem extraneam et tunc est senium aut non est tanto se paucior et tunc est senectus.”

- Taddeo Alderotti, In aphorismorum hypocratis opus expositio (Venice: Apud Iuntas, 1527), 1r–194v, fol. 17r: “Preterea calor semper et incessanter consumit humidum et ad cosumptionem humidi sequitur cosumptio caloris. Preterea corpus humanum est in con-tinua resolutione.”

- On the ages of man in the Middle Ages see John Anthony Burrow, The Ages of Man. A Study in Medieval Writing and Thought (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986); Elizabet Sears, The Ages of Man. Medieval Interpretations of the Life Cycle (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986); Deborah Youngs, The Life Cycle in Western Europe c. 1300–c. 1500 (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2006).

- Taddeo Alderotti, In Isagogas, 369r: “Cum ergo etas sequatur coniunctione humidum radicalis cum calore innato ad eius varietatem sequatur variatio complexionis et ad com-plexionem variatam sequatur variatio virtutis per consequens variatio etatis sequetur varietatem virtutis hoc modo et licet per tempus fiat distinctio non est tamen causa sed potius signum neque omnes concordant in termino vno sed plures.”

- Pietro Torrigiano, Plusquam commentum, I, fol. 10rb–c. “Aetas etiam nullo modo est alter-ans corpus, sed est mensura alterationis corporis viui ex calido et humido in frigidium et siccum à principio vitae vsque in finem eius. Alteratur ergo corpus in ea, sed, quoniam illa alteratio est naturalis, non potest ei opponi causa conseruatua, quia tunc esset possi-bile senium impediri, quod absurdum est.”

- Taddeo Alderotti, In Isagogas, 369r.

- For example Avicenna, Liber Canonis (Venice: P. de Paganinis, 1507 – Reprint Hildesheim, 1964), 1.1.3.3.

- Pietro Torrigiano, Plusquam commentum, I, fol. 15e: “Propter quod, sicut alteratur com-plexio in aetatibus, sic alteratur coaequalitas inhaerens illi per naturam: cuius alteratio, cum sit secundum naturam, non facit minus debere esse corpus simpliciter sanum, max-ime cum illa coaequales comitetur vna secundum speciem, vel vna secundum ambitum suae latitudinis, licet secundum ipsius differentias, vel secundum pares latitudinis sit non vna. Talis namque fuit in complexione suorum seminum proportio contrariorum ad inu-icem, quod in prima aetate corporis generati ex illis seminibus resultauit complexio eius, optime adaequata ad opus, et in secunda, et in tertia, et in quarta similiter, sicut competit naturae aetatis: non enim est par opus in aetatibus, quia non est par complexio: pariter ergo immutabitur et complexio et opus in priori proportione ad omne aliud corpus in eadem aetate, et similiter in iuuentute, et in senectute, et senio.”

- See Marilyn Nicoud, Les régimes de santé au moyen âge I. Naissance et diffusion d’une écriture médicale (XIIIe–Xve siécle) (Rome: École française de Rome, 2007), 12–15.

- Siraisi, Taddeo Alderotti and His Pupils, 293.

- Avicenna, Liber Canonis, 1.4.1.1.

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.19. 251: “Primum enim, quod competit in curatione omnium maniaccrum, est gaudium et laetitia, quoniam illum quod magis, ocet, est solicitudo, et tristitia, et ideo domus debet esse clara, luminosa, sine picturis et debent adesse multa odotifera, et omnes habitantes in ea debent esse pulchri aspectus, omnesque quos timeat et de quibus verecundetur, si enormai egerit, aut fatua loquaru, et ipsi debent multa promittere, et eiam multa localia pulcherrima praesentare, ibique esse instrumenta musica, breuiter, omnia, quae laetificant animam. Attamen si prouenerit ista aegritudo ex nimio gaudio et repentino, aut quia fuir nunciatum ipsum esse ad dignitates maximas subleuatum, aut aliquem es ipsius amicis, tunc bonum esset, quod de illo eodem tristitia induceretur.”

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.19. 251: “Secunda competunt in curatione omnia humectantia, cum passio sit ex sicco, et ideo competunt ipsi somnus, quies, ocium, balnea ante cibum, et cibaria humectantia non oppilantia: qualia sunt gallinae, capones, caro annualis agni, vinum clarum…”

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.20.258.

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.20.258: “Finaliter cum aliud consilium non habemus, imploremus auxilium et consilium vetularum, vt ipsam dehonestent et dissament, quantum possunt: ipsae enim habent artem sagacem, ad hoc plus, quam viri, licet idem dicat Auicenna aliquos esse, qui gaudent audire foetida et illicita. Quaratur igitur vetula turpissima in aspectu cum magnis dentibus, barba, cum turpi et vili habitu, et quae portet subtus gremium, pannum menstruatum, et cum aduenerit philocapta, incipiat dehonestare camisiam suam, dicendo quomodo sit tignosa et ebriosa, quod mingat in lecto, sit epileptica, et impudica, in corpore suo habeat excrescentias enormes cum foetore anhelitus et aliis monibus enormibus, in quibus vetulae sunt edoctae. Si autem ex his persuasionibus nolit dimittere, subito extrahat pannum menstruatum coram facie, portando, dicendo, clamando, talis est amica tua, talis. Et si ne etiam ex his dimiserit, iam non est homo, sed diabolus incarnatus: Fatuitas igitur sua, vlterius secum sit in perditione.”

- Taddeo Alderotti, Consilia, Consilia, XXII, 177: “Dico ergo quod aer suus debet esse humidus valde, ad aliquam caliditatem declinans vel ad temperamentum inter calidum et frigidum.”

- Taddeo Alderotti, Consilia, Consilia, XXII, 177–179.

- Taddeo Alderotti, Consilia, Consilia, XXII, 182.

- Taddeo Alderotti, Consilia, Consilia, XXII, 183–184.

- Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine, 118.

- Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine, 161–162; Piero P. Giorgi & Gian Franco Pasini, ed., Consilia di Taddeo Alderotti (Bologna: Università di Bologna, 1997), 101 n. 9.

- Giorgi & Pasini, Consilia di Taddeo Alderotti, 185 n. 8.

- Taddeo Alderotti, Consilia, Consilia, XXII, 185: “Hoc non conferente, fiat perforatio cranis in parte anteriori capitis et humectetur dura mater cum oleo violato vel oleo boraginis simul mixtis.”

- Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine, 140.

- Dols, “Galen and Islamic Psychiatry,” 248–249.

- Taddeo Alderotti, Consilia, Consilia, CXXII, 326–335.

- Taddeo Alderotti, Consilia, Consilia, CXXII, 335–338.

- Taddeo Alderotti, In Cl. Galeni Micratechnen commentarij, III, Lectio 7, fol. 166va–vb: “Item potest alio modo dici, vt dicamus quantum ad nutriementum competit regimen per simile, quia sicut dictum est per Galienum et 3. de virtutibus naturalibus, nutriemen-tum est perfecta assimilatio nutrientis cum nutritio. Et hoc videntur declinare verba eius 6. de regimine sanitatis, sed quantum ad alias res non naturales conseruatur per aliqualem contrarietatem, que possit reprimere inclinationem factam a qualitate dominante…”

- Taddeo Alderotti, In Cl. Galeni Micratechnen commentari, III, Lectio 7, fol. 166va: “Hiis vero prehabitis dico quod corpus conseruatur dupliciter. Vno quidem modo per comparationem ad inclinationem specialem, que sit per causam intrinsecam, et hoc modo debemus eam conseruare per contraria, que contrariam tante sunt virtutis vt solummodo prohibeant inclinationem, quam facit vincens qualitas in tali corpore, et hoc dico cum talibus contrariis, que virtutem habeant medicine, et hoc ideo dico, quia non debet esse cum cibo, quia cibus debet esse similis corpori quod nutritur, sicut supra dictum est. Alio vero modo conseruamus corpus per comparationem ad mutationem, quam recipit per causam exteriorem, et hoc moco sufficit quod offeramus similia.”

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium medicinae, 2.18.29: “Incipiat dicere horas dominicas, et statim dormiet.”

- For demonic influence and mental disorders, see the chapters of Rider and Katajala-Peltomaa in this compilation.

Contribution (21-46) from Mental (Dis)Order in Later Medieval Europe, edited by Sari Katajala-Peltomaa and Susanna Niiranen (Brill Academic Pub., 03.12.2014), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.