Beer in nineteenth-century America was never just about drinking. It was about identity, industry, labor, politics, and morality.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Beer in nineteenth-century America was more than refreshment. It became a lens through which immigration, industry, politics, and morality were contested. In a century of profound transformation (industrial growth, mass migration, civil war, urbanization) beer was never a bystander. It shaped leisure, work, and identity.

The American brewing industry began the century modest, reliant on colonial ale traditions. By its end, it had become industrialized, dominated by nationally known brands, and embedded in debates about temperance and vice. To understand the century’s beer is to confront the changing face of America itself.

Colonial Legacies and Early 19th Century Brewing

British Ale Traditions in the Early Republic

In the early republic, beer meant ale. British styles dominated, brewed in small batches by local artisans. The product was fragile, often souring quickly, which meant most beer was consumed close to where it was made. Taverns carried ale alongside cider and whiskey, the latter cheaper and more plentiful.1

Beer was respected but not central. It was a minor partner in the republic’s early drinking culture, overshadowed by stronger spirits. Yet its very modesty created space for later transformation.

Constraints and Shifts

Transport was a problem. Without refrigeration or modern bottling, beer spoiled quickly. Long-distance shipping was rare. The result was localism: each city had its own small brewers, producing for a neighborhood clientele.

But cities were growing. Immigration and industrialization pushed demand upward. Brewing was ready to expand, if only new methods and new consumers could push it past its limits.

Immigration and the Transformation of American Beer

German Immigrants and Lager Beer

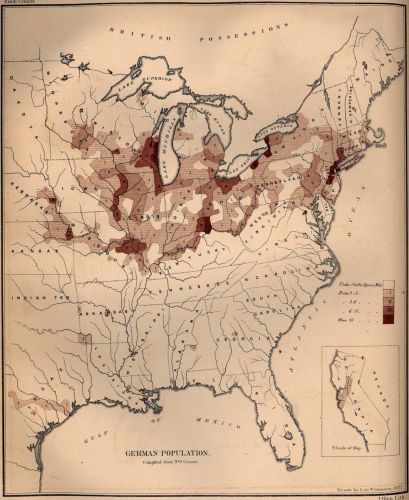

The mid-nineteenth century brought waves of German immigrants, and with them came lager. Unlike the heavier ales, lager was crisp, lighter in color, bottom-fermented, and could be stored for longer periods. Germans regarded it as essential to their identity, and they transplanted both the beverage and the culture of drinking that surrounded it.2

Lager was revolutionary. It demanded new techniques and patience, longer fermentation times, cooler temperatures; but once established, it reshaped American tastes. The old dominance of ale began to fade, and lager became the nation’s beer.

Ethnic Enclaves and Beer Culture

German immigrants did not just brew; they drank together in distinctive spaces. Beer gardens, often attached to breweries, became social centers. They mixed leisure, music, family life, and politics. To spend a Sunday in a beer garden was to reaffirm community.

For nativists, however, this German Sunday was a provocation. It violated Protestant sabbatarian sensibilities. Beer, in their eyes, symbolized foreignness, indiscipline, and threat. What immigrants celebrated as conviviality others condemned as vice.

Industrialization of Brewing

Technological Innovations

The second half of the century transformed brewing. Refrigeration allowed year-round lager production. Pasteurization reduced spoilage. Bottling plants and railroads enabled beer to travel across states. Brewing ceased to be purely local and became industrial.3

The Rise of National Breweries

Milwaukee and St. Louis became brewing capitals. Anheuser-Busch, Pabst, Schlitz, names that endure today, were products of this era. They built not only breweries but networks of distribution, advertising, and political influence. Beer became a commodity of national scope, no longer confined to city taverns.

Labor and Brewing

Industrialization brought labor issues. Breweries employed thousands, many of them immigrants. Workers struck over hours, pay, and conditions. Brewing was not immune from the wider labor unrest of industrial America. Indeed, beer itself sometimes lubricated solidarity, saloons doubled as meeting halls for unions.

Beer and Social Life

Beer Gardens and Saloons

Beer gardens embodied German cultural transfer: family-friendly, open-air, musical. By contrast, saloons emerged as more exclusively male, urban, working-class spaces. Saloons proliferated in cities, often tied to breweries that supplied them on favorable terms.

Saloons were not simply about drink. They were places to socialize, gamble, hear news, and plot politics. For immigrants, they offered a sense of belonging in a new country. For reformers, they were dens of corruption.

Beer and Politics

Politicians understood saloons as essential. Machine politics in cities like New York and Chicago used them as outposts of patronage. Beer bought loyalty, and bartenders acted as political brokers. The pint became a medium of power.

Beer and Class Identity

For middle-class reformers, beer was ambiguous. On one hand, they argued it was less destructive than whiskey. On the other, its association with immigrants, saloons, and urban disorder made it suspicious. Beer was caught in a cultural crossfire, celebrated as wholesome by some, demonized by others.

Beer and the Temperance Movement

Roots of Temperance

Temperance reformers initially targeted spirits, not beer. Whiskey consumption in the early nineteenth century was staggering, and reformers sought to curb its damage. Beer was sometimes praised as a moderate alternative, a drink less likely to ruin men and households.4

Growing Hostility to Beer and Saloons

By mid-century, temperance advocates began to fold beer into their critique. The saloon was their symbol of vice, and beer flowed at its center. Beer had once been positioned as moderate, but by the 1870s and 1880s it was associated with corruption, foreignness, and the erosion of Protestant morality.

Beer in the Crosshairs of Prohibition

By the end of the century, beer was squarely in the crosshairs. The Anti-Saloon League and allied groups painted beer as no better than whiskey. The temperance movement’s hostility was not just moral but cultural: a rejection of immigrant customs and urban politics. The battles of the nineteenth century set the stage for Prohibition in the twentieth.

Regional Patterns and Distinctiveness

Midwest as Brewing Heartland

Milwaukee and St. Louis became synonymous with beer. Access to grain, immigrant labor, and river and rail transport made the Midwest ideal. By late century, Milwaukee alone boasted dozens of breweries, with a handful of giants dominating national distribution.

Urban East Coast

New York and Philadelphia retained strong brewing cultures, often tied to ethnic enclaves. Breweries served German, Irish, and other immigrant neighborhoods. Here, diversity was both strength and vulnerability: no single city could dominate as Milwaukee did, but beer was central to everyday life.

Rural Beer Cultures

Beer was not exclusively urban. Immigrant farmers, particularly Germans in the Midwest, brewed at home and in small community breweries. Rural beer culture was modest but persistent, a quieter counterpart to the industrial giants.

Conclusion

Beer in nineteenth-century America was never just about drinking. It was about identity, industry, labor, politics, and morality. German immigrants made lager the national style, industrialists built empires of brewing, and reformers mobilized against saloons. Beer mirrored the nation: diverse, contested, commercial, and deeply symbolic.

By 1900, beer was both triumph and target. It had become a national beverage, embedded in daily life, but also the focus of campaigns that would culminate in Prohibition. To study nineteenth-century beer is to glimpse a nation fermenting with change: foamy, bitter, intoxicating, and unfinished.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Gregg Smith, Beer in America: The Early Years 1587–1840 (Boulder: Brewers Publications, 1998), 112.

- Maureen Ogle, Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer (Orlando: Harcourt, 2006), 33–36.

- Jonathan Rees, Refrigeration Nation: A History of Ice, Appliances, and Enterprise in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), 87.

- W. J. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 212–215.

Bibliography

- Mittelman, Amy. Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer. New York: Algora, 2007.

- Ogle, Maureen. Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer. Orlando: Harcourt, 2006.

- Rees, Jonathan. Refrigeration Nation: A History of Ice, Appliances, and Enterprise in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013.

- Rorabaugh, W. J. The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

- Smith, Gregg. Beer in America: The Early Years 1587–1840. Boulder: Brewers Publications, 1998.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.12.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.