The same nation that welcomed millions also imposed racial hierarchies and exclusionary laws that defined who could belong.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

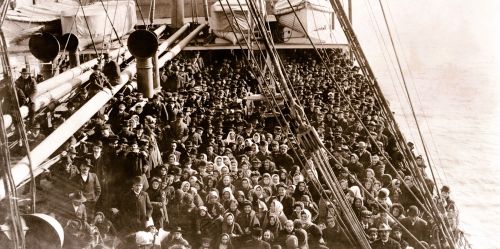

Between the 1850s and the 1920s, the United States became the central destination in what historians often call the “Age of Mass Migration.” During these seven decades, more than thirty million Europeans crossed the Atlantic, fleeing crop failures, land shortages, famine, and political upheaval in their home countries.1 The combination of push factors in Europe and powerful pull factors in America (the promise of industrial employment, cheap land, and relative social mobility) produced one of the largest movements of people in recorded history. For the United States, this influx marked not simply a demographic expansion but a deep transformation of its economic structure, labor markets, and cultural composition.

The new arrivals entered a society still defining itself after the Civil War, amid a revolution in transportation, urban growth, and industrial capitalism. Immigrants were both celebrated and scorned: hailed by industrialists as the lifeblood of the modern economy yet condemned by nativists as an existential threat to American identity.2 Their presence provoked a national argument about who could become “American,” what cultural uniformity meant in a democracy built on diversity, and how open a republic’s borders should remain in an age of economic turbulence.

Economically, immigration fueled the rapid industrial growth that made the United States the world’s leading economy by the early twentieth century. Immigrants labored in mines, mills, and factories; they laid the railroads that bound the continent; and they swelled the urban centers that became engines of innovation and conflict alike.3 Yet these same workers faced overcrowded housing, low wages, and discrimination that confined many to the margins of prosperity. Their fortunes were determined not only by market demand but by the politics of assimilation, the volatility of public opinion, and the emerging machinery of immigration control.

By the 1920s, after decades of political agitation and cultural anxiety, the United States imposed strict quotas that ended the age of mass migration and redefined national boundaries in racial and cultural terms.4 What follows examines that pivotal era through three intertwined lenses: the social and ideological views of immigrants within American society, the economic impacts of their labor, and their uneven journeys toward assimilation. In doing so, it seeks to understand how migration reshaped both the material and moral landscape of a nation still wrestling with the meaning of freedom, equality, and belonging.

Causes, Scale, and Patterns of Migration

The “Age of Mass Migration” did not emerge spontaneously but as the culmination of intertwined global pressures. Throughout much of nineteenth-century Europe, population growth outpaced economic opportunity. Industrialization created uneven prosperity: while cities such as Manchester and Berlin expanded rapidly, agrarian regions across Ireland, Italy, and Eastern Europe experienced worsening poverty and displacement. Repeated crop failures, including the devastating Irish potato famine of the 1840s, drove millions to seek survival abroad.5 In Southern and Eastern Europe, smallholders struggled against declining land availability and rising taxes, while the mechanization of agriculture and enclosure policies concentrated wealth among landowners. In the Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires, persecution of ethnic minorities and Jews added a political and religious dimension to economic migration.6

The transatlantic journey itself was made possible by technological revolution. The transition from sail to steam shortened the voyage from several weeks to about ten days by the 1880s, cutting costs and mortality.7 The establishment of regular lines by companies such as Cunard and White Star connected Liverpool, Bremen, and Naples to New York, Boston, and Philadelphia with remarkable efficiency. These improvements transformed migration into a mass movement rather than an elite venture. Letters home, known as America letters, circulated tales of high wages and abundant land, creating powerful “chain migrations” that linked entire villages in Europe to enclaves in the United States.8

On the American side, economic expansion generated insatiable demand for labor. The aftermath of the Civil War opened vast territories in the Midwest and West, while industrial cities in the Northeast grew into centers of steel, textile, and machinery production. Employers viewed European immigrants as an ideal labor source: inexpensive, abundant, and, in their eyes, less inclined to unionize than native workers.9 The Homestead Act of 1862 and subsequent land grants also encouraged migration by offering real property to settlers willing to cultivate it. For many, this represented not only economic hope but a moral ideal of independence unavailable in the stratified societies they left behind.

Migration patterns evolved over time. The so-called “old immigration” from Northern and Western Europe (Britain, Ireland, Germany, and Scandinavia) dominated until the 1880s. Thereafter, the “new immigration” from Southern and Eastern Europe (Italy, Poland, Russia, and the Balkans) transformed the ethnic composition of arrivals.10 By 1910, immigrants and their children comprised more than one-third of the U.S. population, forming distinct urban enclaves in New York’s Lower East Side, Chicago’s South Side, and the industrial towns of Pennsylvania and Ohio.11 Historians estimate that between 1850 and 1914 roughly thirty million Europeans entered the United States, making it the largest voluntary migration in modern history.12

The openness of American borders during this era was as significant as its eventual closure. Until the 1880s, federal immigration law was minimal, and state or private organizations handled most processing. Restrictions began with the Page Act of 1875 and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, both reflecting racialized fears rather than economic logic.13 The crescendo came with the Quota Acts of the early 1920s, culminating in the Immigration Act of 1924, which set strict national-origin limits favoring Northern Europeans.14 The door that had admitted tens of millions now swung nearly shut. In retrospect, the age of mass migration was both an epoch of extraordinary openness and the seedbed of modern restrictionism, a paradox that continues to shape American identity and policy.

Public and Elite Views of Immigration: Support and Resistance

Reactions to the surge of European immigration were deeply ambivalent. While many Americans regarded newcomers as indispensable to national growth, others feared that they threatened cultural cohesion and democratic stability. The “melting pot” ideal, popularized in the early twentieth century, suggested a hopeful synthesis of cultures, yet its optimism was never universal. The divide between enthusiasm and hostility toward immigrants mirrored the broader tension between an expanding industrial economy and an anxious social order still haunted by inequality and change.

Among business leaders, the attitude was largely pragmatic. Industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie and Henry Frick openly endorsed immigration as the foundation of American productivity.15 They viewed labor mobility as essential to the expansion of steel, rail, and textile industries, which depended on a steady supply of low-wage, often unskilled workers. Railroad companies and mining firms even sent agents to Europe to recruit labor directly, advertising the promise of high wages and freedom.16

The press of the era occasionally echoed this optimism, celebrating the immigrant as a symbol of vitality and enterprise. For reformers of a liberal bent, particularly those in the settlement-house movement, immigration represented a moral challenge rather than a threat: an opportunity to uplift the poor through education, civic training, and social services. Jane Addams and her colleagues at Hull House in Chicago, for instance, regarded the immigrant poor as integral to the moral advancement of the nation, arguing that democracy would be strengthened by inclusion rather than exclusion.17

Yet this idealism collided with a rising tide of nativism. From the 1850s Know-Nothing movement to the Immigration Restriction League founded in 1894, anti-immigrant sentiment became an enduring feature of political discourse.18 The rhetoric of “Americanism” invoked a mythic Anglo-Saxon purity, warning that Catholic, Jewish, and Eastern Orthodox immigrants were incapable of assimilation. Popular magazines and political cartoons portrayed newcomers as racially inferior or morally suspect, associating them with anarchism, socialism, and urban vice.19 The 1886 Haymarket bombing in Chicago and the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901, both linked in the public imagination to foreign radicals, intensified fears that immigration imperiled social order.20

Elite intellectuals lent this prejudice a veneer of scientific legitimacy. The spread of eugenics in the early twentieth century transformed old racial hierarchies into pseudo-biological arguments for restriction. Harvard economist and Immigration Restriction League founder Prescott F. Hall claimed that immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe threatened to “degrade the American stock.”21 The 1911 report of the federal Dillingham Commission, spanning over forty volumes, codified this bias in bureaucratic language, concluding that “new” immigrants were less assimilable and more prone to criminality than their Northern European predecessors.22 Though the report’s data were often flawed, it shaped the intellectual foundation for the quota system that would soon follow.

At the same time, immigrant communities resisted these narratives by asserting their Americanness through civic participation and cultural expression. Ethnic newspapers, labor unions, and fraternal organizations, such as the Jewish Arbeiter Ring or the Italian Sons of Italy, served both defensive and integrative functions.23 They provided mutual aid, political education, and a platform for public engagement, demonstrating that assimilation was not mere conformity but negotiation. Many immigrants embraced American political ideals even as they challenged economic injustice, forming the backbone of the early labor movement. The paradox of the era lay in this simultaneity: immigrants were castigated as unfit for democracy while actively expanding its social and economic reach.

The debate over immigration thus revealed more than prejudice; it exposed a nation in the midst of defining its own modern identity. Advocates of restriction claimed to protect the republic from “foreign corruption,” while progressives argued that diversity was the republic’s strength. The battle lines drawn during this period (between openness and exclusion, cosmopolitanism, and nationalism) would persist long after the gates closed in 1924.24 In retrospect, these conflicting visions form a mirror of the American experience itself: a country perpetually torn between the fear of difference and the promise of renewal.

Economic Impacts on the United States

The economic transformation of the United States during the age of mass migration cannot be separated from the labor and enterprise of immigrants. Between 1860 and 1920, the nation’s industrial output increased more than tenfold, and immigrants supplied a substantial share of that expansion.25 They constructed the railroads that linked Atlantic ports to western mines, staffed the steel mills of Pittsburgh, and filled the urban tenements that powered New York’s garment industry.26 Immigration provided the manpower necessary for the shift from an agrarian to an industrial economy, enabling employers to hold down wages while maintaining rapid growth. Without this vast labor supply, the pace of American industrialization would likely have slowed dramatically.

At the same time, economic integration between native and immigrant workers was neither frictionless nor uniform. Many employers divided their labor forces along ethnic lines, exploiting cultural and linguistic barriers to deter unionization.27 Industrial foremen often assigned newly arrived Italians, Poles, or Slovaks to the most dangerous and poorly paid jobs, while reserving supervisory positions for earlier immigrant groups such as the Irish or Germans. This hierarchy reproduced old-world prejudices in a new economic context, reinforcing patterns of occupational stratification. Nevertheless, empirical research suggests that the arrival of immigrants did not significantly depress wages for native workers in the long term.28 The dynamic American economy expanded fast enough to absorb new labor, and by the 1920s, productivity gains offset most localized wage pressures.

The geographic distribution of immigrants also influenced regional development. Urban centers like New York, Chicago, and Boston became hubs of innovation precisely because of their diverse labor markets. Economists have found that cities with higher concentrations of European immigrants in the early twentieth century later exhibited greater per capita income growth and lower poverty rates.29 The diffusion of skills and social networks among immigrant communities fostered entrepreneurship, particularly in small-scale manufacturing and retail trade. Jewish and Italian immigrants, for example, created dense clusters of neighborhood businesses that later evolved into broader commercial networks.30 In this way, immigration not only filled existing labor needs but generated new forms of capital accumulation.

In agriculture, too, the immigrant footprint was profound. Scandinavian and German settlers transformed the Upper Midwest into one of the world’s most productive farming regions.31 Their advanced techniques (crop rotation, dairy specialization, and cooperative marketing) helped modernize rural America. Meanwhile, immigrant labor from Southern and Eastern Europe sustained harvests in the Midwest and industrial agriculture in California.32 The combination of cheap land and abundant labor allowed American agricultural exports to dominate world markets by 1900, linking the nation’s farms to global trade networks that in turn attracted more migrants.

However, the benefits of immigration were unevenly distributed. Industrialists reaped enormous profits, while many immigrants endured poverty and perilous working conditions.33 The absence of robust labor protections left them vulnerable to exploitation, leading to tragedies such as the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, where 146 garment workers, mostly young immigrant women, died behind locked doors.34 Such events galvanized the early labor reform movement and drew public attention to the human cost of economic progress. Labor unrest, including the Homestead and Lawrence strikes, revealed the extent to which immigrant workers had become the shock troops of industrial America’s moral reckoning.

Ultimately, immigration accelerated both growth and inequality. The same inflows that fueled the rise of a modern economy also magnified social divisions between classes and ethnic groups. Yet in historical perspective, the economic legacy of the age of mass migration remains overwhelmingly positive. Long-run analyses show that regions with high historical immigration continue to experience higher incomes, greater innovation, and more diversified economies than comparable regions with low immigration.35 In short, immigrants not only helped build the American economy, they laid the foundations of its enduring dynamism.

Labor Market Assimilation and Socioeconomic Mobility

The story of immigration in the United States is not only one of arrival but of adaptation. For millions who crossed the Atlantic during the age of mass migration, economic success depended on their ability to navigate new labor markets, social hierarchies, and cultural expectations. While the conditions they encountered were often harsh, the long-run record suggests that most immigrant groups achieved measurable upward mobility, particularly by the second generation.36

Upon arrival, many immigrants entered the lowest rungs of the labor market, working as dockhands, miners, domestic servants, and factory operatives.37 Employers rarely recognized skills acquired in Europe, and language barriers limited access to higher-paying occupations. Yet within a single generation, immigrants demonstrated substantial occupational convergence with native-born workers. Using linked census data, economic historians Ran Abramitzky and Leah Boustan found that European immigrants in the early twentieth century closed roughly half the earnings gap with natives within fifteen years of arrival.38 This rate of economic assimilation rivals or exceeds that of modern immigrants, suggesting that the American economy of that era rewarded persistence and mobility despite pervasive discrimination.

Regional variation played a decisive role. In industrial centers such as Chicago and Cleveland, immigrants advanced through ethnic networks that connected employment opportunities, housing, and credit.39 Neighborhood institutions (churches, mutual-aid societies, and immigrant banks) facilitated savings and home ownership. In smaller towns and agricultural regions, where labor mobility was more limited, advancement often came through self-employment. Jewish, Italian, and Greek immigrants in particular established small retail and craft businesses that provided both autonomy and resilience during economic downturns.40 For many, entrepreneurship functioned as a path to dignity in a society that often denied them equality.

The second generation, the children of immigrants, became the true barometer of assimilation. By the 1930s, native-born children of immigrants attained levels of education and income comparable to or higher than those of the U.S.-born population of native parentage.41 Public schools played an especially powerful role in this transformation, serving both as instruments of linguistic assimilation and as gateways to civic identity. The sociologist Robert Park’s “race relations cycle” model, which described a progression from contact to accommodation to assimilation, captured what he and his colleagues observed in Chicago’s ethnically mixed neighborhoods.42 Although criticized for oversimplifying a complex process, Park’s model reflected an empirical truth: the children of European immigrants were largely integrated into American social and economic life within two generations.

Women’s labor offers a more complicated picture. Female immigrants faced dual constraints of gender and ethnicity. Many worked in textile and garment factories, where wages were low but opportunities for collective organization were growing.43 Others entered domestic service, an occupation that provided exposure to American language and customs but little chance for mobility. Yet immigrant women often became economic anchors of their households, managing finances and ensuring children’s education. Their wages, though modest, supplemented family income and accelerated intergenerational advancement.44 By the early twentieth century, women from immigrant families were increasingly represented in clerical, teaching, and nursing professions, signaling gradual social transformation.45

Assimilation was not merely economic but cultural and political. Participation in labor unions, civic organizations, and electoral politics signaled commitment to the American democratic project. The rise of the American Federation of Labor and later the Congress of Industrial Organizations depended heavily on immigrant membership and leadership.46 Language acquisition followed a similar trajectory: by 1930, over 90 percent of second-generation immigrants were fluent in English.47 Intermarriage rates between different European groups also rose steadily, dissolving older ethnic boundaries. The process was uneven and at times painful, but by the 1920s, the children of Ellis Island immigrants had largely remade the American working and middle classes.

Nevertheless, assimilation had its limits. Structural barriers, residential segregation, and racialized notions of whiteness excluded many non-European groups from similar upward mobility.48 The success of European immigrants often depended on their eventual inclusion within the category of “white,” a privilege denied to contemporaneous migrants from Asia, Mexico, and the Caribbean. Thus, the apparent universality of immigrant success must be understood within the racial hierarchies of the time. What appeared as open opportunity was, in practice, a selective process that expanded citizenship for some while narrowing it for others.

Challenges, Limits, and Critiques

For all its narratives of success and opportunity, the age of mass migration was marked equally by hardship, exclusion, and moral contradiction. The economic and social ascent of millions coexisted with the exploitation of millions more. Historians have increasingly emphasized that the same processes that propelled industrial progress also generated profound inequalities and systemic discrimination.49

One major limitation of the immigrant experience was the precariousness of work. Industrial employment, especially in mining, construction, and manufacturing, was notoriously dangerous. Accidents, illness, and job insecurity haunted daily life, while few immigrants had access to compensation or legal recourse.50 The growth of tenement housing in cities such as New York and Chicago turned poverty into a visible urban condition. Jacob Riis’s photographs in How the Other Half Lives (1890) exposed overcrowded and unsanitary dwellings in which entire families lived in single rooms without ventilation or plumbing.51 Reformers and journalists drew public attention to these conditions, yet improvement was slow and uneven. Philanthropic aid often carried paternalistic overtones, treating immigrants less as citizens than as subjects of moral correction.

Return migration further complicates the success narrative. Roughly one-quarter of European immigrants who arrived in the United States during this era eventually returned to their homelands.52 Many had intended from the outset to work temporarily, save money, and reestablish themselves abroad, a pattern known as “sojourning.” This cyclical migration undermines the myth of permanent settlement and reveals that the motives of migrants were often economic rather than ideological. Those who returned home brought new skills, savings, and ideas that reshaped European local economies, illustrating that the consequences of migration were transnational, not solely American.53

The exploitation of immigrant labor also intersected with racial and gender hierarchies. Employers frequently recruited Southern and Eastern Europeans to displace African American or Asian workers, reinforcing divisions among marginalized groups.54 Ethnic stratification in the workplace thus became a tool of labor control. Women and children were especially vulnerable, often paid half the wage of men for equivalent work.55 The persistence of child labor in immigrant neighborhoods until federal regulation in the 1910s revealed the structural constraints that kept families dependent on every possible income earner. Moral reformers attributed this to cultural backwardness rather than economic necessity, reinforcing ethnic stereotypes rather than addressing industrial exploitation.

The racial dimension of restrictionism remains one of the most significant critiques of the period. The quota system established in the 1920s was not an inevitable response to labor-market saturation but a deliberate effort to engineer the nation’s demographic composition.56 The architects of immigration law used the pseudoscience of eugenics to justify numerical hierarchies that privileged Northern Europeans and excluded others. By defining national identity in racial terms, they reified a narrow conception of citizenship that persisted through the twentieth century. The system’s enduring legacy, visible in the exclusion of Asian immigrants until 1965, reveals how the closure of the gates was as much about race and power as about economics.57

Historians have also critiqued the triumphalist portrayal of assimilation that dominated mid-century scholarship. The narrative of steady integration overlooked the persistence of poverty and cultural isolation in many immigrant enclaves.58 It also ignored those who never “made it,” whose struggles were masked by the success of others. Contemporary research emphasizes that assimilation was not a uniform process but a contested one, mediated by class, gender, and geography.59 The very notion of a single, linear immigrant experience collapses under scrutiny, replaced by a mosaic of outcomes that better reflect the complexity of American society during its most transformative era.

By reframing the age of mass migration through these critiques, historians have revealed both its achievements and its contradictions. Immigration expanded freedom for many while constraining it for others; it democratized opportunity yet entrenched inequality. The paradox of inclusion and exclusion defined not only this period but the American project itself. The tensions born in that era (between openness and control, diversity and hierarchy) continue to echo through every subsequent debate on immigration and identity.60

Conclusion

The age of mass migration stands as one of the most transformative episodes in American history. Between the 1850s and the 1920s, the United States absorbed tens of millions of newcomers, reshaping its cities, industries, and social ideals. Their arrival not only altered the demographic landscape but redefined what it meant to be American in an era of industrial capitalism, racial hierarchy, and expanding democracy. These immigrants carried the ambitions of a continent and, in realizing them, changed the trajectory of a nation.

The evidence of their impact is both tangible and enduring. Immigrant labor powered the industrial revolution that made the United States an economic superpower, while immigrant communities cultivated the pluralistic culture that remains its defining strength.61 They brought skills, languages, and traditions that diversified the nation’s intellectual and cultural life, producing what historian Oscar Handlin famously called “the uprooted,” people who remade themselves while remaking the country.62 The material achievements of industrial expansion, from skyscrapers to railways, cannot be separated from the sweat and sacrifice of those who built them. Yet their legacy extends beyond physical infrastructure to the democratic ideals they embodied: perseverance, adaptation, and faith in opportunity.

Still, the era’s contradictions cannot be overlooked. The same nation that welcomed millions also imposed racial hierarchies and exclusionary laws that defined who could belong. The Immigration Act of 1924 closed the gates in the name of preserving a narrow cultural homogeneity, revealing how fragile the ideal of openness could be.63 Economic progress came at the cost of labor exploitation, environmental degradation, and urban inequality. Assimilation, though often celebrated, demanded erasure as much as inclusion. The American Dream that immigrants pursued was real yet conditional, accessible to some and denied to others.

Modern debates over migration still echo the anxieties and hopes of that earlier age. The questions remain remarkably similar: how to balance economic need with social cohesion, openness with security, national identity with human mobility.64 The lessons of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries suggest that immigration has been, and continues to be, a source of renewal rather than decline. Its challenges are genuine, but its contributions to national vitality are irrefutable. The story of mass migration, with all its hardship and aspiration, reminds us that the American experiment has never been static. It is a process of constant reinvention, a continuing dialogue between the rooted and the uprooted, the native and the newcomer, in the ongoing creation of a democratic people.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Ran Abramitzky and Leah Boustan, “Immigration in American Economic History,” Journal of Economic Literature 54, no. 4 (2016): 1318–1320.

- Erika Lee, America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States (New York: Basic Books, 2019), 89–96.

- Susan Carter et al., eds., Historical Statistics of the United States: Millennial Edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 1–12; Hirschman and Mogford, “Immigration and the American Industrial Revolution from 1880 to 1920,” Social Science Research 1:38(4) (2012): 897-220.

- Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 17–20.

- Kevin H. O’Rourke, “The European Grain Invasion, 1870–1913,” Journal of Economic History 57, no. 4 (1997): 775–801.

- Jonathan D. Sarna, American Judaism: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 63–65.

- Drew Keeling, “Transport Capacity Management and Transatlantic Migration, 1900-1914,” Research in Economic History 19 (2007): 217–252.

- Donna R. Gabaccia, Italy’s Many Diasporas (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000), 45–47.

- John Bodnar, The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), 22–25.

- Aristide R. Zolberg, A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006), 218–221.

- U.S. Census Bureau, Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910 Population (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1913), Table 26.

- Ran Abramitzky and Leah Boustan, “Immigration in American Economic History,” Journal of Economic Literature 54, no. 4 (2016): 1321.

- Erika Lee, At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 31–34.

- Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 17–20.

- Andrew Carnegie, The Gospel of Wealth and Other Timely Essays (New York: Century, 1900), 47–49.

- Donna R. Gabaccia, Foreign Relations: American Immigration in Global Perspective (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 92–93.

- Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull-House (New York: Macmillan, 1910), 129–133.

- Tyler Anbinder, Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 14–17.

- John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1955), 87–90.

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 2 (New York: International Publishers, 1947), 274–278.

- Daniel J. Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985), 64–66.

- U.S. Immigration Commission, Reports of the Immigration Commission (Dillingham Commission), 1911, Senate Document No. 747 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1911), vol. 1, x–xii.

- Hasia R. Diner, Hungering for America: Italian, Irish, and Jewish Foodways in the Age of Migration (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991), 112–118.

- Erika Lee, America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States (New York: Basic Books, 2019), 162–165.

- Susan B. Carter et al., eds., Historical Statistics of the United States: Millennial Edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), Table Ba470–486.

- Charles Hirschman and Elizabeth Mogford, “Immigration and the American Industrial Revolution from 1880 to 1920,” Social Science Research 1:38(4) (2012): 897-920.

- John Bodnar, The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), 49–53.

- Claudia Goldin, “The Political Economy of Immigration Restriction in the United States, 1890–1921,” in The Regulated Economy: A Historical Approach to Political Economy, ed. Claudia Goldin and Gary D. Libecap (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 225–257.

- Faridul Islam and Saleheen Khan, “The Long-Run Impact of Immigration on Labor Market in an Advanced Economy: Evidence from U.S. Data,” International Journal of Social Economics 42:4 (2015): 356-357.

- Hasia R. Diner, A Time for Gathering: The Second Migration, 1820–1920 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 142–146.

- Jon Gjerde, The Minds of the West: Ethnocultural Evolution in the Rural Middle West, 1830–1917 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 87–90.

- Richard Steven Street, Beasts of the Field: A Narrative History of California Farmworkers, 1769–1913 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004), 293–298.

- David Montgomery, The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865–1925 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 115–118.

- Leon Stein, The Triangle Fire (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1962), 59–63.

- Nathan Nunn, Nancy Qian, and Sandra Sequeira, “Immigrants and the Making of America,” Review of Economic Studies 89, no. 1 (2022): 313–340.

- Ran Abramitzky and Leah Boustan, Streets of Gold: America’s Untold Story of Immigrant Success (New York: PublicAffairs, 2022), 41–46.

- John Bodnar, The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), 63–67.

- Ran Abramitzky, Leah Boustan, and Katherine Eriksson, “A Nation of Immigrants: Assimilation and Economic Outcomes in the Age of Mass Migration,” Journal of Political Economy 122, no. 3 (2014): 467–506.

- Dominic A. Pacyga, Chicago: A Biography (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 118–121.

- Hasia R. Diner, Hungering for America: Italian, Irish, and Jewish Foodways in the Age of Migration (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 142–148.

- Barry R. Chiswick and Timothy J. Hatton, “International Migration and the Integration of Labor Markets,” in Handbook of Cliometrics, ed. Claude Diebolt and Michael Haupert (Heidelberg: Springer, 2016), 943–968.

- Robert E. Park, “Human Migration and the Marginal Man,” American Journal of Sociology 33, no. 6 (1928): 881–893.

- Annelise Orleck, Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the United States, 1900–1965 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 11–16.

- Donna R. Gabaccia, From the Other Side: Women, Gender, and Immigrant Life in the U.S., 1820–1990 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 52–55.

- Alice Kessler-Harris, Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 141–144.

- David Montgomery, The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865–1925 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 273–276.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, Population, Volume II (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1933), Table 37.

- Matthew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 39–44.

- Donna R. Gabaccia and Dirk Hoerder, eds., Connecting Seas and Connected Ocean Rims: Indian, Atlantic, and Pacific Oceans and China Seas Migrations from the 1830s to the 1930s (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 173–176.

- David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz, Deadly Dust: Silicosis and the Politics of Occupational Disease in Twentieth-Century America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 14–18.

- Jacob A. Riis, How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890), 39–45.

- Drew Keeling, “Repeat Migration between Europe and the United States, 1870–1914,” In The Birth of Modern Europe, edited by Laura Cruz and Joel Mokyr, 157-186. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2003.

- Adam McKeown, Melancholy Order: Asian Migration and the Globalization of Borders (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 67–70.

- Nell Irvin Painter, Standing at Armageddon: A Grassroots History of the Progressive Era (New York: W. W. Norton, 2011), 88–91.

- Walter I. Trattner, Crusade for the Children: A History of the National Child Labor Committee and Child Labor Reform in America (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1970), 45–49.

- Daniel J. Tichenor, Dividing Lines: The Politics of Immigration Control in America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 122–126.

- Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 23–27.

- John Bodnar, The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), 201–204.

- Nancy Foner, From Ellis Island to JFK: New York’s Two Great Waves of Immigration (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 27–31.

- Erika Lee, America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States (New York: Basic Books, 2019), 198–202.

- Ran Abramitzky and Leah Boustan, Streets of Gold: America’s Untold Story of Immigrant Success (New York: PublicAffairs, 2022), 289–292.

- Oscar Handlin, The Uprooted: The Epic Story of the Great Migrations That Made the American People (Boston: Little, Brown, 1951), vii–xii.

- Daniel J. Tichenor, Dividing Lines: The Politics of Immigration Control in America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 142–145.

- Nancy Foner, From Ellis Island to JFK: New York’s Two Great Waves of Immigration (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 202–205.

Bibliography

- Abramitzky, Ran, and Leah Boustan. Streets of Gold: America’s Untold Story of Immigrant Success. New York: PublicAffairs, 2022.

- ———. “Immigration in American Economic History.” Journal of Economic Literature 54, no. 4 (2016): 1318–1321.

- Abramitzky, Ran, Leah Boustan, and Katherine Eriksson. “A Nation of Immigrants: Assimilation and Economic Outcomes in the Age of Mass Migration.” Journal of Political Economy 122, no. 3 (2014): 467–506.

- Addams, Jane. Twenty Years at Hull-House. New York: Macmillan, 1910.

- Anbinder, Tyler. Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Bodnar, John. The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985.

- Carnegie, Andrew. The Gospel of Wealth and Other Timely Essays. New York: Century, 1900.

- Carter, Susan B., et al., eds. Historical Statistics of the United States: Millennial Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Chiswick, Barry R., and Timothy J. Hatton. “International Migration and the Integration of Labor Markets.” In Handbook of Cliometrics, edited by Claude Diebolt and Michael Haupert, 943–968. Heidelberg: Springer, 2016.

- Diner, Hasia R. A Time for Gathering: The Second Migration, 1820–1920. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

- ———. Hungering for America: Italian, Irish, and Jewish Foodways in the Age of Migration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Foner, Philip S. History of the Labor Movement in the United States. Vol. 2. New York: International Publishers, 1947.

- Foner, Nancy. From Ellis Island to JFK: New York’s Two Great Waves of Immigration. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Gabaccia, Donna R. Foreign Relations: American Immigration in Global Perspective. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

- ———. From the Other Side: Women, Gender, and Immigrant Life in the U.S., 1820–1990. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

- ———. Italy’s Many Diasporas. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000.

- Gabaccia, Donna R., and Dirk Hoerder, eds. Connecting Seas and Connected Ocean Rims: Indian, Atlantic, and Pacific Oceans and China Seas Migrations from the 1830s to the 1930s. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

- Gjerde, Jon. The Minds of the West: Ethnocultural Evolution in the Rural Middle West, 1830–1917. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Goldin, Claudia. “The Political Economy of Immigration Restriction in the United States, 1890–1921.” In The Regulated Economy: A Historical Approach to Political Economy, edited by Claudia Goldin and Gary D. Libecap, 225–257. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

- Handlin, Oscar. The Uprooted: The Epic Story of the Great Migrations That Made the American People. Boston: Little, Brown, 1951.

- Higham, John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1955.

- Hirschman, Charles and Elizabeth Mogford. “Immigration and the American Industrial Revolution from 1880 to 1920.” Social Science Research 1:38(4) (2012): 897-220.

- Islam, Faridul and Saleheen Khan. “The Long-Run Impact of Immigration on Labor Market in an Advanced Economy: Evidence from U.S. Data.” International Journal of Social Economics 42:4 (2015): 356-357.

- Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Keeling, Drew. “Repeat Migration between Europe and the United States, 1870–1914.” In The Birth of Modern Europe, edited by Laura Cruz and Joel Mokyr, 157-186. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2003.

- ———. “Transport Capacity Management and Transatlantic Migration, 1900-1914.” Research in Economic History 19 (2007): 217–252.

- Kevles, Daniel J. In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Kessler-Harris, Alice. Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Lee, Erika. At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- ———. America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States. New York: Basic Books, 2019.

- McKeown, Adam. Melancholy Order: Asian Migration and the Globalization of Borders. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

- Montgomery, David. The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865–1925. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- Ngai, Mae M. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Nunn, Nathan, Nancy Qian, and Sandra Sequeira. “Immigrants and the Making of America.” Review of Economic Studies 89, no. 1 (2022): 313–340.

- O’Rourke, Kevin H. “The European Grain Invasion, 1870–1913.” Journal of Economic History 57, no. 4 (1997): 775–801.

- Orleck, Annelise. Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the United States, 1900–1965. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

- Pacyga, Dominic A. Chicago: A Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Painter, Nell Irvin. Standing at Armageddon: A Grassroots History of the Progressive Era. New York: W. W. Norton, 2011.

- Park, Robert E. “Human Migration and the Marginal Man.” American Journal of Sociology 33, no. 6 (1928): 881–893.

- Riis, Jacob A. How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890.

- Rosner, David, and Gerald Markowitz. Deadly Dust: Silicosis and the Politics of Occupational Disease in Twentieth-Century America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

- Sarna, Jonathan D. American Judaism: A History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

- Stein, Leon. The Triangle Fire. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1962.

- Street, Richard Steven. Beasts of the Field: A Narrative History of California Farmworkers, 1769–1913. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004.

- Tichenor, Daniel J. Dividing Lines: The Politics of Immigration Control in America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Trattner, Walter I. Crusade for the Children: A History of the National Child Labor Committee and Child Labor Reform in America. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1970.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, Population, Volume II. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1933.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910 Population. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1913.

- U.S. Immigration Commission. Reports of the Immigration Commission (Dillingham Commission), 1911. Senate Document No. 747. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1911.

- Zolberg, Aristide R. A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.14.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.