Dangerous foods were an inescapable part of medieval life, shaping dietary choices and shaping the strategies households used to navigate an unpredictable food landscape.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Food in the medieval era was never simply nourishment. It carried risks that shaped daily life for peasants, townspeople, and royal households alike. The instability of grain supplies, the limits of preservation, and the realities of urban crowding produced an environment in which bread could maim, meat could sicken, and fashionable delicacies could kill.1 These dangers were not peripheral to medieval food culture. They were part of its structure, embedded in economic pressures, regulatory failures, and the practical limits of medieval cooking and trade.

Bread, the foundation of most European diets, was particularly vulnerable. Municipal records from London, Paris, and numerous English towns document fines against bakers for adulterating loaves with sand, bran, dust, or other fillers when grain prices rose.2 Poor-quality flour, damp storage, and the ease with which sellers could disguise inferior grain made bread an unpredictable staple. The dangers extended beyond grain. Meat, fish, and fast food sold in medieval cities carried their own hazards. Unsanitary butchering conditions, inadequate preservation, and the absence of microbial knowledge left consumers exposed to corruption and food poisoning.3

Elite tables offered no guarantee of safety. Certain high-status foods, including lamprey and porpoise, carried well-known risks. Chroniclers attributed the death of King Henry I in 1135 to “a surfeit of lampreys,” reflecting both the cultural popularity of the dish and the recognized danger of consuming improperly prepared fish.4 Blood-based dishes, though common in some regions, were also viewed with suspicion by medical writers who associated animal blood with corruption and toxicity. These anxieties shaped culinary practices across social boundaries, influencing what could be safely eaten and under what conditions.

Understanding these dangers provides insight into medieval life beyond the kitchen. Food regulation, municipal policing, and household strategies of risk management reveal how medieval people negotiated the uncertainties of survival.5 Dangerous foods illuminate broader concerns about trust, morality, civic order, and the fragility of health in a world where contamination was often invisible and illness frequently fatal. Examining these practices across sources shows how medieval societies confronted everyday peril at the table with a mix of regulation, habit, and hope.

Bad Bread and the Hazards of Adulteration

Bread was the cornerstone of medieval European diets, yet it was also one of the most dangerous foods available. Grain shortages, fluctuating prices, and uneven quality created opportunities for bakers to reduce costs by adulterating flour or manipulating weight. Municipal governments attempted to regulate these abuses through the Assize of Bread and Ale, but the frequency of fines recorded in civic archives shows that adulteration remained a persistent threat.6 The hazards of bread were therefore both nutritional and structural, arising from economic pressures that encouraged fraudulent practices even as bread remained essential to survival.

Adulteration took several forms. Civic records from London describe bakers punished for adding sand, dust, bran, or other fillers to stretch limited grain supplies. Scholars examining court rolls note that inspectors routinely found loaves that were underweight, falsely priced, or baked from spoiled flour.7 Such adulterants could damage teeth, irritate the digestive system, or conceal the use of grain that had decayed in damp storage. The prevalence of these fines indicates that medieval consumers often faced uncertainty regarding the quality of their most basic food.

Poor storage conditions compounded the risks. Grain kept in unventilated barns or cellars could develop mold or become infested with insects, yet would still be milled and sold during periods of scarcity. Medieval authorities recognized this problem. Some English and French towns required grain to be inspected before milling, but enforcement varied widely, especially during periods of famine or political instability.8 The lack of uniform standards meant that consumers frequently purchased bread made from grain that was nutritionally compromised or visibly corrupted.

Contemporary writers commented on the dangers of adulterated bread, reflecting both public concern and regulatory frustration. Dietary manuals warned that bread made from spoiled flour or impure grain could cause digestive distress or illness. Chroniclers noted that famine years produced bread of visibly poor quality, sometimes mixed with substitutes such as ground peas, beans, or even bark.9 Although these substitutions were not always malicious, they produced loaves with unpredictable effects on health, especially among the poor, who relied on lower grades of bread such as horse bread or maslin loaves.

Regulation provided some safeguard, but its effectiveness was uneven. The Assize of Bread and Ale mandated strict weight and price ratios tied to grain costs, and bakers who violated these rules faced amercements or public humiliation in devices such as the pillory. Yet scholars have shown that these penalties were not always a deterrent. Fines were often small, repeat offenders were common, and periods of high prices strained regulatory capacity.10 As a result, the quality of bread varied dramatically by region, season, and social class.

For medieval consumers, danger was therefore intertwined with necessity. Bread adulteration reflected broader patterns of economic vulnerability, environmental unpredictability, and limited regulatory reach. The risks associated with bread were not simply the result of unscrupulous bakers but were rooted in the structural challenges of feeding large urban populations with inconsistent grain supplies.11 These conditions made bread both indispensable and hazardous, shaping the daily experience of medieval food insecurity.

Dangerous Meat: Spoilage, Contamination, and Unsanitary Preparation

Meat was one of the most consistently dangerous foods in the medieval diet because its safety depended on careful butchery, proper preservation, and rapid consumption, none of which could be reliably guaranteed. Urban populations created high demand for fresh meat, yet medieval markets lacked the infrastructure to maintain sanitary conditions. Warm temperatures, slow transport, and the absence of refrigeration meant that contamination could begin within hours. Municipal records from London and continental cities frequently document butchers fined for selling putrid meat or for keeping carcasses in unsuitable conditions.12 These entries provide some of the most direct evidence for the hazards associated with meat.

In London, the regulations governing meat sellers were extensive, suggesting that problems of spoilage were persistent. The Liber Albus, a collection of London’s civic ordinances, includes rules requiring that butchers dispose of offal outside city walls and prohibits the sale of any flesh considered “corrupt.”13 Despite these rules, surviving court records show repeated violations. Carcasses were washed in polluted water, cuts were sold long after freshness had passed, and scraps were reboiled into stews sold cheaply to the poor. These practices reveal both the economic pressures on sellers and the difficulty of enforcing food safety in crowded urban environments.

Preservation techniques such as salting, smoking, and curing offered some protection, but these methods were inconsistent and often poorly executed. Salted meats relied on high-quality salt and thorough packing, yet inferior salt or inadequate brining allowed bacterial growth to persist. Archaeological analyses of animal bones from medieval English sites show butchery marks consistent with large-scale salting operations, but documentary evidence stresses that even preserved meats could spoil if stored in damp or unventilated spaces.14 The line between edible and unsafe meat was therefore thin, especially for lower-income households that relied on cheaper cuts or older preserved supplies.

Medical writers of the period recognized these dangers, even if they lacked modern understanding of pathogens. Authors of regimina sanitatis, the health manuals popular in England, France, and Italy, warned that meat from older animals, improperly cooked flesh, or corrupt cuts could produce illness, indigestion, or fevers. Their concerns were grounded in humoral theory, but they accurately identified spoilage and contamination as recurring risks.15 These texts show that medieval dietary knowledge incorporated practical observations of foodborne illness even without a microbial framework.

The dangers of meat reveal broader structural conditions in medieval life. Contamination was not simply the result of negligence but reflected the challenges of dense urban populations, limited preservation methods, and varying degrees of civic enforcement. Even wealthier households faced risk when supply chains broke down or when fashionable dishes involved complex preparation.16 Meat, like bread, illustrates how medieval people navigated an environment where food safety depended on a combination of regulation, household vigilance, and simple luck.

Hazardous Fish: Lampreys and Other Marine Dangers

Fish occupied an important place in the medieval diet, particularly because ecclesiastical fasting rules required abstention from meat on numerous days throughout the year. Yet fish was also one of the most unpredictable and dangerous foods available, especially in regions dependent on long-distance transport. Lamprey was the most notorious example. Considered a delicacy by medieval elites, it could cause severe illness if improperly prepared. Chroniclers such as Henry of Huntingdon attributed the death of King Henry I in 1135 to “a surfeit of lampreys,” reflecting both the dish’s cultural status and the recognized risk associated with eating it.17 Whether or not lampreys caused his death, the association demonstrates the medieval understanding that certain fish were dangerous when not handled properly.

The risk derived from both biological and logistical factors. Lampreys contain high quantities of blood and bile that require careful removal. Medieval recipes emphasized meticulous cleaning, but surviving culinary texts also show that complex preparations increased the likelihood of error.18 Transport added further hazards. In inland areas, fish often traveled long distances packed in barrels or baskets with limited salting or icing. Even urban centers near rivers could receive fish in compromised condition, particularly during warm seasons or periods of high demand. Dietary manuals and household accounts mention spoiled fish as a recurring concern, demonstrating that medieval consumers recognized the difficulty of keeping fish fresh.19

Regulation attempted to address some of these problems. In London, ordinances required fishmongers to display their wares openly and prohibited the sale of fish deemed corrupt or “stinking.” Despite these rules, court records show that fines for selling spoiled fish were common. Sellers sometimes attempted to disguise deterioration by reboiling or re-spicing fish to mask odor.20 This practice was particularly dangerous because spices could conceal visual or olfactory signs of spoilage without removing underlying contamination. As with meat, enforcement varied according to season, supply, and municipal resources.

Hazardous fish illuminate wider issues in medieval food culture. Lamprey, porpoise, and other marine foods reflected elite tastes that sometimes placed prestige above safety. Urban fish markets, meanwhile, show the tension between demand, perishability, and limited preservation technology. These conditions created an environment in which even cherished dishes were shadowed by risk.21 The consumption of fish in the medieval era therefore reveals not only culinary preferences but also the structural challenges of maintaining a stable and safe food supply.

Blood as Food and Poison: Beliefs and Practices

Animal blood occupied an uneasy place in medieval cuisine. It appeared in numerous dishes across Europe, including puddings, sauces, and certain festival foods, yet it was also associated with corruption, impurity, and danger in medical and religious writing. Dietaries and regimina sanitatis warned that blood was “hot” and “thick,” qualities that could harm digestion or disrupt humoral balance if consumed improperly.22 These concerns reflected both physiological theories and the practical observation that blood spoiled rapidly, making it a risky ingredient in regions lacking reliable preservation methods. The tension between its culinary uses and its perceived toxicity makes blood a revealing case study in medieval risk perception.

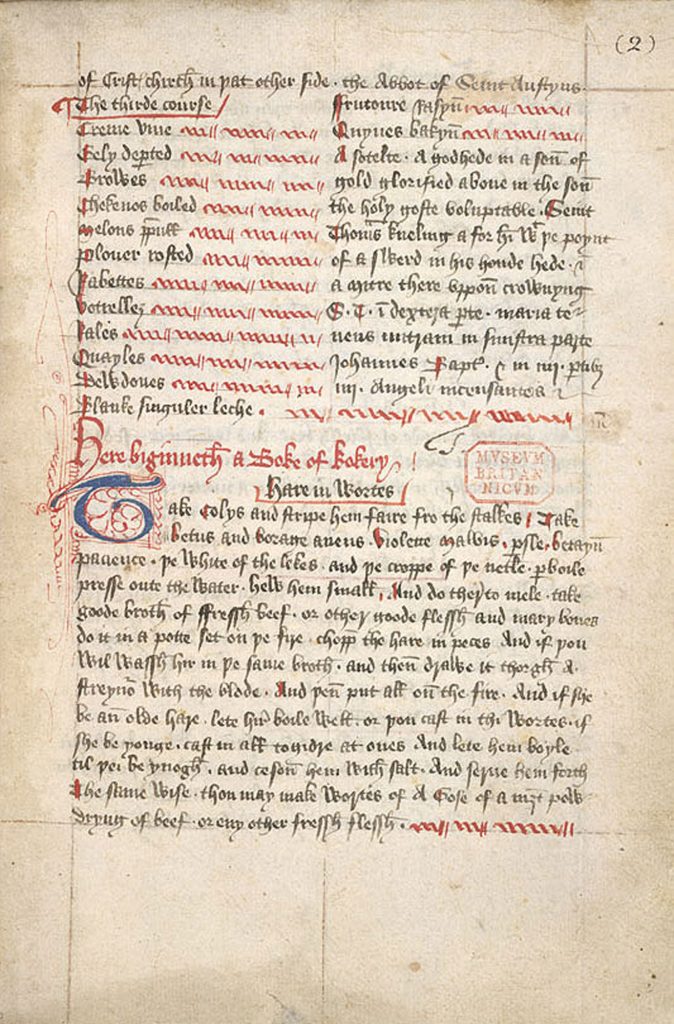

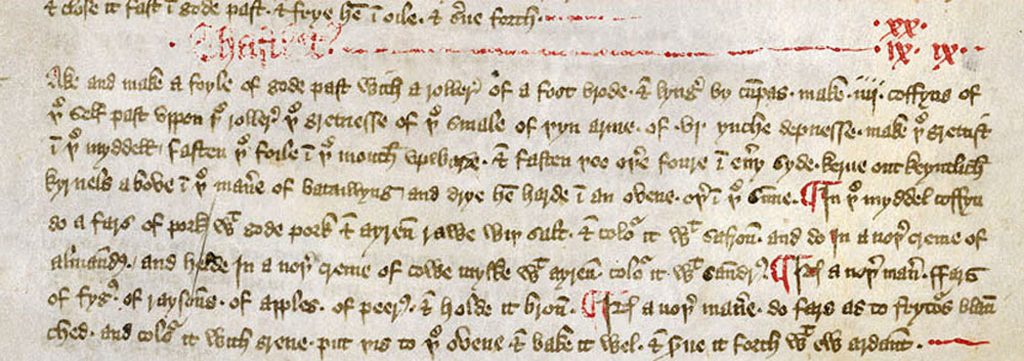

Culinary sources confirm that blood-based preparations were well known. The Forme of Cury, a late fourteenth-century English cookbook compiled by the cooks of Richard II, includes recipes that thicken sauces or enrich dishes using animal blood.23 Other manuscripts describe puddings or mixes combining blood with spices, grains, or fat. These dishes required careful handling because blood deteriorates quickly, especially in warm conditions. Medieval households without immediate access to fresh slaughter were particularly susceptible to contamination, a fact that medical writers implicitly recognized when they cautioned readers against consuming blood from animals of uncertain health or from sources unfit for cooking.

Popular belief added another layer of risk. Several chronicles and anecdotal accounts mention ox blood as a feared poison, especially when mixed into omelettes or broths. While these stories often carried moral or cautionary tones, they demonstrate a widespread cultural association between blood and danger.24 The fear was not entirely unfounded. Without modern understanding of coagulation and bacterial growth, medieval observers could easily interpret the sudden illness that followed a spoiled or contaminated dish as evidence of blood’s inherent toxicity. These stories reveal how culinary danger became intertwined with broader anxieties about purity, intent, and trust.

Blood’s ambiguous status shaped medieval foodways in practical ways. Some cities prohibited the sale of blood except at designated stalls or during specific times, attempting to limit consumption to its freshest state. In other places, blood was reserved for specialized dishes produced by professional cooks, who presumably had more experience handling it safely.25 These measures reflect both regulatory concern and the recognition that blood could be valuable when used well yet hazardous when used carelessly. Its dual identity as nourishment and potential poison exemplifies the complex balancing act medieval people performed when navigating the risks present in their daily diet.

Porpoise and Other Hazardous Elite Foods

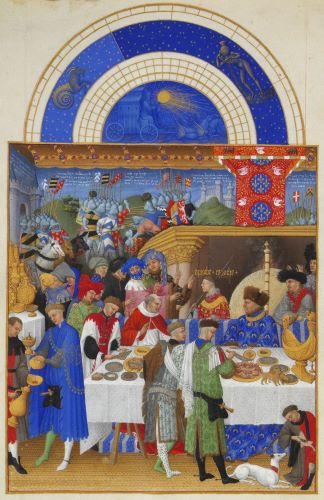

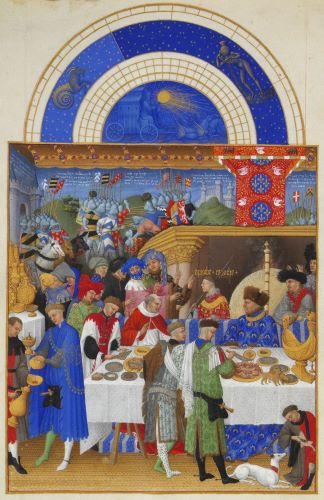

Elite medieval cuisine frequently embraced foods that carried significant risks, especially when their preparation demanded specialized knowledge or when ingredients spoiled easily. Porpoise is one of the clearest examples. Classified as “fish” for ecclesiastical purposes, porpoise appeared on aristocratic and monastic tables during fast days, which increased its demand.26 Surviving household accounts from royal and noble estates show frequent purchases of porpoise meat, often preserved in salt or cooked fresh when coastal access allowed. Its rarity made it fashionable. Its composition made it dangerous. The high fat and blood content required careful handling, and improper butchering or storage could render porpoise unsafe long before it reached the table.

Culinary manuscripts confirm that porpoise was prepared in elaborate ways that introduced further risk. The Forme of Cury contains a recipe for “porpays,” instructing cooks to combine porpoise flesh with wine, spices, and saffron, while other manuscripts describe puddings made from porpoise blood and grease.27 These dishes relied on complex mixtures and extended cooking times, conditions that made spoilage difficult to detect. Even skilled cooks could err when balancing ingredients that aged differently or reacted unpredictably in warm kitchens. The complexity of elite dishes therefore magnified the dangers inherent in rare or easily corrupted ingredients.

Elite tastes extended beyond porpoise. Medieval courts and monasteries consumed a range of specialty foods whose safety depended on timing, environment, and technique. Household rolls from the English royal wardrobe list purchases of exotic fish, preserved marine mammals, and birds that required delicate preparation.28 The prestige attached to such foods often outweighed concerns about spoilage or contamination, especially when their consumption asserted status or fulfilled religious expectations during fasting seasons. For elite diners, the culinary risks of these ingredients were sometimes accepted as part of their cultural value.

Church regulations played an important role in shaping these practices. Because porpoise and certain marine animals were classified as “fish,” they were permitted during Lent and on fast days, creating periods of intense demand. Monastic accounts from Cluny, Westminster, and other major houses include entries for porpoise purchased for communal meals.29 Increased demand during these seasons stressed supply chains and heightened the risk of receiving meat that was already compromised. This pattern helps explain why porpoise appears in regulation and complaint more frequently than its relative rarity in ordinary diets might suggest.

The dangers associated with elite foods reveal how status, scarcity, and religious observance intersected with food safety. While poorer households faced risks from adulteration and urban contamination, elites encountered hazards created by their own culinary preferences and the fragile trade networks that supplied them.30 Porpoise and similar foods thus occupy an important place in the broader landscape of medieval dietary risk, showing that privilege did not eliminate danger but reshaped its form.

Fast Food and Street Vendors: Urban Risks in Medieval Cities

Urban food markets provided medieval city dwellers with quick and affordable meals, yet these same markets exposed consumers to significant health risks. Cookshops, pie sellers, and tavern kitchens operated with minimal oversight, cramped space, and limited access to clean water.26 London, Paris, York, and other cities maintained ordinances aimed at regulating fast food, but enforcement was inconsistent. As a result, the food sold in these establishments was often prepared from low-quality ingredients or handled in unsanitary conditions.31 The speed and volume of production increased the likelihood of contamination, making fast food a recognized source of illness.

Court records and civic ordinances supply vivid evidence of the dangers. London’s mayoral courts repeatedly fined cookshop owners for serving “stinking” pies, reboiled meat, watered ale, and fish cooked in rancid oil.32 Archaeological excavations of medieval urban sites support these textual accounts. Middens associated with cookshops often contain bones from older or diseased animals, suggesting that vendors purchased the cheapest cuts available. The combination of inferior ingredients and rapid preparation created a predictable environment for foodborne illness, especially among poorer residents who relied on these establishments for daily meals.

Travelers’ accounts reinforce this picture. Some chroniclers warned that “street meats” and ready-cooked dishes could be harmful when purchased from vendors of uncertain reputation. While these remarks sometimes reflect elite bias against urban lower-class food culture, they also indicate an awareness that street foods were unpredictable in freshness and quality.33 The volatility of urban supply chains amplified this risk. Vendors frequently purchased leftover or unsold goods from butchers and fishmongers at discounted rates, creating a secondary economy of food already nearing spoilage.

Fast food in medieval cities thus reveals a distinct form of culinary danger rooted in urban density, economic inequality, and weak enforcement of public health measures. Cookshops and street vendors played an essential role in feeding working populations, but their operations often skirted the limits of safety.34 Unlike the risks associated with elite foods such as lamprey or porpoise, the dangers of urban fast food disproportionately affected common people whose limited resources forced them to accept food that was affordable but hazardous. These conditions illustrate how medieval urban life shaped patterns of dietary risk in ways that paralleled broader social and economic divides.

Dangerous Dishes: Questionable Ingredients and Hazardous Techniques

Not all medieval food dangers came from spoilage or adulteration. Some risks derived directly from the recipes themselves. Medieval cooks worked within a culinary tradition that prized experimentation, symbolism, and spectacle. This creativity produced dishes that relied on ingredients or techniques considered unsafe by modern standards. Many medieval cookbooks describe preparations that involve long exposure to warm temperatures, inadequate boiling of animal products, or the incorporation of ingredients that modern food science categorizes as hazardous.35 Although medieval diners lacked a microbial framework for understanding illness, they nonetheless recognized that certain dishes were unpredictable and required careful handling.

One risk came from the use of ingredients that have since fallen out of culinary practice. The Liber Cure Cocorum, a fifteenth-century English recipe collection, includes directions for dishes involving animal parts that spoil rapidly or require extensive cleaning, such as brains, entrails, and specific organ mixtures.36 While these foods were not inherently unsafe, they demanded meticulous preparation in conditions where cross-contamination was easy to introduce. Recipes that mixed raw eggs with animal blood or partially cooked fish with spices also created dishes that could become hazardous if left at room temperature during long feast preparations.

Complex multi-stage recipes added further danger. Medieval feasts often required cooks to parboil meat, leave it cooling for hours, and then roast or stew it again later in the day. This process appears throughout manuscripts such as the Forme of Cury and Le Ménagier de Paris, both of which describe dishes that involve extended periods between cooking stages.37 In environments without refrigeration, such intervals increased the risk of bacterial growth. The elaborate nature of elite cuisine, with its emphasis on presentation and layered flavors, inadvertently heightened the likelihood of contamination.

Some recipes used thickening agents or preservatives that posed their own risks. Isinglass, a gelatin made from fish bladders, appears frequently in English and French culinary manuscripts as a clarifying agent. Its preparation required careful washing and boiling, yet surviving household accounts show that it was not always handled properly.38 Similarly, certain curing agents used in fish and meat dishes varied widely in composition and quality. Their inconsistent application created uneven preservation results that were difficult for consumers to detect visually.

Even sophisticated kitchens could produce dangerous results when ingredients were rare or poorly understood. Elite dishes involving marine mammals, exotic birds, or complex organ blends appear in several high-status manuscripts. These recipes were often symbolic, associated with feasting rituals or courtly display, and required technical expertise to execute safely. The risks were masked by the prestige of the dish.39 The pursuit of novelty and luxury sometimes placed elite diners at greater risk than their poorer counterparts, whose simpler diets exposed them to different but less elaborate hazards.

Conclusion

Dangerous foods were an inescapable part of medieval life, shaping dietary choices and shaping the strategies households used to navigate an unpredictable food landscape. From adulterated bread to contaminated meat and hazardous fish, the risks found in ordinary meals reflected the deep structural challenges of medieval food production, regulation, and preservation. These dangers were not limited to the poor. Elite dishes involving porpoise, lamprey, and complex feast preparations introduced their own forms of vulnerability, revealing that privilege could alter the kind of risk one faced but could not eliminate it entirely.

When viewed together, the dangers present in medieval kitchens and markets reveal a spectrum of hazards tied to environment, economy, culture, and belief. Fast food vendors in crowded cities, cooks preparing multi-stage dishes, and bakers stretching grain supplies all operated within systems that made food safety inconsistent. Medical writers, civic authorities, and household managers recognized these problems even without modern scientific knowledge. Their responses, whether regulatory or practical, illustrate how medieval people understood and attempted to control the threats woven into daily sustenance.

These patterns show that the medieval diet was shaped by a constant negotiation between necessity and danger. The foods that sustained life could also undermine it, and medieval people developed habits, regulations, and culinary traditions that balanced flavor, faith, and fear. Examining these risks uncovers a world in which food functioned not only as nourishment but as a marker of status, a site of regulation, and a reflection of the fragility of health in a pre-industrial society.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Christopher Dyer, Everyday Life in Medieval England (London: Hambledon and London, 1994), 113–18.

- Carolyn Steel, Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives (London: Vintage, 2009), 42–45; and the Assize of Bread and Ale, in Statutes of the Realm, vol. 1 (London: Record Commission, 1810), 199–201.

- Martha Carlin, Food and Eating in Medieval Europe (London: Hambledon Press, 1998), 87–95.

- Henry of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum, ed. and trans. Diana Greenway (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 730–32.

- P. W. Hammond and Anne Helm, Food and Feast in Medieval England (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 1993), 55–64.

- James Davis, Baking for the Common Good: Bread and Regulation in Medieval England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 18–22.

- Carlin, Food and Eating in Medieval Europe, 35–39.

- John Hatcher, Plague, Population, and the English Economy 1348–1530 (London: Macmillan, 1977), 41–44.

- Bridget Ann Henisch, Fast and Feast: Food in Medieval Society (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1976), 54–58.

- Christopher Dyer, Standards of Living in the Later Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 116–20.

- P. J. P. Goldberg, Medieval England: A Social History 1250–1550 (London: Arnold, 2004), 102–5.

- Carlin, Food and Eating in Medieval Europe, 87–91.

- Henry T. Riley, ed., Liber Albus: The White Book of the City of London (London: Richard Griffin and Company, 1861), 292–94.

- Umberto Albarella, “Meat Consumption and Production in Town and Country,” in Town and Country in the Middle Ages: Contrasts, Contacts and Interconnections, 1100-1500, Giles, K. and Dyer, C., eds., (London: Routledge, 2005): 45–54.

- Faith Wallis, Medieval Medicine: A Reader (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 310–15.

- Henisch, Fast and Feast, 63–68.

- Henry of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum, 730–32.

- Constance B. Hieatt and Sharon Butler, eds., Curye on Inglysch: English Culinary Manuscripts of the Fourteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 98–101.

- Henisch, Fast and Feast, 71–75.

- Carlin, Food and Eating in Medieval Europe, 94–97.

- Dyer, Everyday Life in Medieval England, 120–23.

- Wallis, Medieval Medicine, 322–28.

- Hieatt and Butler, eds., Curye on Inglysch, 112–14.

- Henisch, Fast and Feast, 82–85.

- Martha Carlin, Medieval Southwark (London: Continuum, 1996), 143–45.

- C. M. Woolgar, The Culture of Food in England, 1200–1500 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 88–90.

- Hieatt and Butler, eds., Curye on Inglysch, 78–79.

- S. H. Rigby, English Society in the Later Middle Ages (London: Macmillan, 1995), 144–48.

- Barbara Harvey, Living and Dying in England, 1100–1540: The Monastic Experience (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 112–15.

- Christopher Woolgar, Selections from English Wills, 1200–1550 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 211–14.

- Carlin, Medieval Southwark, 137–41.

- Henry T. Riley, ed., Memorials of London and London Life (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1868), 520–23.

- Henisch, Fast and Feast, 101–4.

- Dyer, Everyday Life in Medieval England, 124–27.

- Allen J. Grieco, “Food Preparation and Culinary Techniques in the Middle Ages,” in Food: A Culinary History, ed. Jean-Louis Flandrin and Massimo Montanari (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 302–9.

- Rudolf Grewe and Constance B. Hieatt, eds., The “Liber Cure Cocorum” (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 45–52.

- Constance B. Hieatt, Brenda Hosington, and Sharon Butler, eds., The “Forme of Cury” (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 121–26; and Le Ménagier de Paris, ed. Georgine Brereton and Janet Ferrier (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981), 158–63.

- Woolgar, The Culture of Food in England, 162–65.

- Rigby, English Society in the Later Middle Ages, 144–48.

Bibliography

- Albarella, Umberto. “Meat Consumption and Production in Town and Country,” in Town and Country in the Middle Ages: Contrasts, Contacts and Interconnections, 1100-1500, Giles, K. and Dyer, C., eds. London: Routledge (2005): 45–54.

- Brereton, Georgine, and Janet Ferrier, eds. Le Ménagier de Paris. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981.

- Carlin, Martha. Food and Eating in Medieval Europe. London: Hambledon Press, 1998.

- —- Medieval Southwark. London: Continuum, 1996.

- Davis, James. Baking for the Common Good: Bread and Regulation in Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Dyer, Christopher. Everyday Life in Medieval England. London: Hambledon and London, 1994.

- —-. Standards of Living in the Later Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Goldberg, P. J. P. Medieval England: A Social History 1250–1550. London: Arnold, 2004.

- Grégoire, Jean-Louis Flandrin, and Massimo Montanari, eds. Food: A Culinary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999. (For the chapter by Allen J. Grieco.)

- Grewe, Rudolf, and Constance B. Hieatt, eds. The “Liber Cure Cocorum”. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Harvey, Barbara. Living and Dying in England, 1100–1540: The Monastic Experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Hatcher, John. Plague, Population, and the English Economy 1348–1530. London: Macmillan, 1977.

- Henisch, Bridget Ann. Fast and Feast: Food in Medieval Society. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1976.

- Henry of Huntingdon. Historia Anglorum. Edited and translated by Diana Greenway. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Hieatt, Constance B., and Sharon Butler, eds. Curye on Inglysch: English Culinary Manuscripts of the Fourteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Hieatt, Constance B., Brenda Hosington, and Sharon Butler, eds. The “Forme of Cury”. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Riley, Henry T., ed. Liber Albus: The White Book of the City of London. London: Richard Griffin and Company, 1861.

- —-. Memorials of London and London Life. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1868.

- Rigby, S. H. English Society in the Later Middle Ages. London: Macmillan, 1995.

- Statutes of the Realm, Vol. 1. London: Record Commission, 1810. (For the Assize of Bread and Ale.)

- Steel, Carolyn. Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives. London: Vintage, 2009.

- Wallis, Faith, ed. Medieval Medicine: A Reader. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

- Woolgar, C. M. Selections from English Wills, 1200–1550. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- —-. The Culture of Food in England, 1200–1500. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.20.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.