Broquière’s Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer stands as a unique record of the political and military conditions of the fifteenth century Eastern Mediterranean.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A Burgundian Traveler in a Fractured Mediterranean

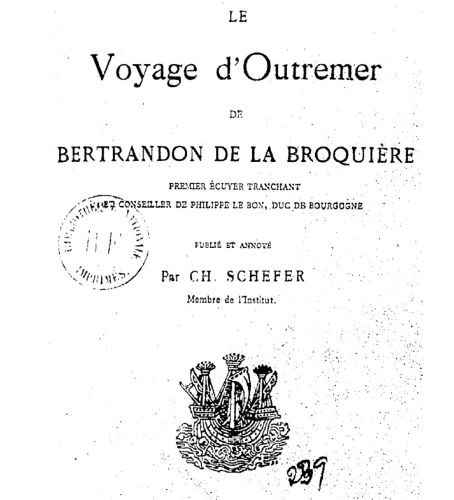

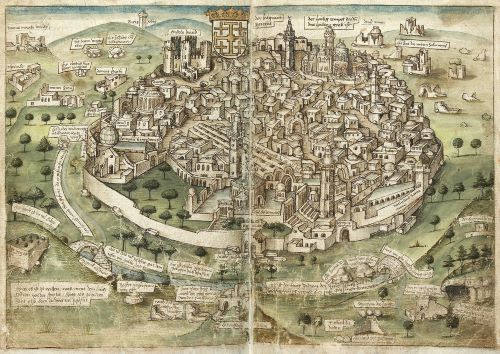

Bertrandon de la Broquière occupies a distinctive place among late medieval travelers because his account blends the personal curiosity of pilgrimage with the political objectives of a court deeply invested in the idea of crusading revival. He undertook his journey to the Eastern Mediterranean in 1432 and 1433 while serving Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, who sought reliable intelligence about the political landscape of the Near East.1 The resulting narrative, Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer, survives as a detailed record of his encounters with rulers, soldiers, merchants, and local guides across Ottoman and Mamluk territories. Its scope extends far beyond the expectations of traditional pilgrimage literature, since Broquière observed roadways, fortifications, supply conditions, and other logistical matters relevant to Burgundian strategic interests.2

His work was composed in French upon his return and was intended for a princely audience rather than for general circulation.3 The Burgundian court under Philip the Good nurtured an elaborate chivalric identity and expressed renewed interest in crusading ventures during the first half of the fifteenth century. This environment gave shape to Broquière’s perspective. His account provided information that Philip hoped would illuminate the feasibility of a large-scale expedition against the expanding Ottoman Empire, which posed growing challenges to Christian powers in both Europe and the Levant. The political tensions of this period, marked by shifting alliances and territorial instability, make Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer a valuable source for understanding the strategic concerns of Western rulers during the decades preceding the fall of Constantinople.

Although Broquière wrote within a crusading framework, his observations frequently transcend the polemical tone of earlier Western travel narratives. He displayed an unusual attentiveness to the customs, military structures, and administrative practices of the societies he visited.4 His interactions with local populations, often facilitated by his adoption of regional dress, allowed him to move through contested spaces in ways that illuminate both the risks and possibilities of cross-cultural travel in the fifteenth century. These moments reveal how political intelligence could emerge from the embodied experience of movement through foreign territories.

The narrative stands at the intersection of diplomacy, espionage, and pilgrimage, offering insight into the ways Western courtiers evaluated the potential for renewed crusading in a Mediterranean world transformed by Ottoman expansion. Its value lies not only in Broquière’s detailed descriptions but also in its ability to show how late medieval rulers interpreted the feasibility of military intervention.5 For historians, Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer provides a rare glimpse of the mechanisms through which information flowed from the frontier back to the courts of Europe. It also demonstrates the ways that travel writing functioned as a political tool during the last major phase of crusading ideology.

Burgundian Crusading Ambitions and the Political Logic of Travel

Philip’s interest in crusading shaped the political environment in which Broquière undertook his journey. The Burgundian duchy presented itself as a defender of Christian interests at a moment when the Ottoman Empire was consolidating its power in the Balkans and threatening regions that Europeans regarded as strategically vital.6 Philip positioned Burgundy as a leader capable of organizing a renewed crusade. His court cultivated chivalric ideals and hosted elaborate ceremonies that revived symbols and rhetoric associated with earlier crusading efforts. These ambitions created a need for accurate information about the political and military conditions of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Broquière’s mission reflects the pragmatic turn in Burgundian crusading thought. While earlier crusading appeals often emphasized spiritual obligation, fifteenth century rulers were increasingly concerned with practical feasibility.7 Philip required knowledge of roads, fortifications, river crossings, coastal defenses, and the internal rivalries among regional powers. Broquière’s travels were designed to gather firsthand observations that could inform potential military coordination. His ability to move between Ottoman and Mamluk territories reveals the flexible diplomatic strategies that the Burgundians employed in order to expand their influence in a politically fractured landscape.

The Burgundian court itself was a setting where politics and ceremony converged. Philip’s administration developed an extensive network of agents who collected information from across Europe and the Near East.8 Broquière’s background as a courtier made him a suitable figure for an assignment that required both diplomatic discretion and familiarity with chivalric ideals. He could assess whether crusading efforts aligned with the ambitions of Burgundy’s ruling elite, who envisioned a role for their duchy that exceeded its territorial size.

The Eastern Mediterranean that Broquière entered was defined by shifting alliances and active conflict. The Mamluk Sultanate governed Syria and Egypt, while the Ottomans controlled regions of Anatolia and the Balkans.9 The tension between these powers shaped the political atmosphere in which Broquière gathered information. His travels occurred during a period when European powers were trying to understand the extent of Ottoman expansion. These broader developments created the context in which his observations would later be evaluated by Philip’s counselors and military planners.

Broquière’s journey demonstrates how travel could serve as a form of political reconnaissance. He did not travel alone as a pilgrim, nor did he function solely as a diplomatic envoy. Instead, he combined elements of both roles in order to collect intelligence that could influence Burgundian policy.10 His mission exemplifies a moment in which European rulers used travel not only as a means of devotion or cultural encounter but also as a method for gathering strategic knowledge. This approach provides insight into how late medieval courts understood the relationship between mobility, diplomacy, and military planning.

The Textual Identity of Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer: Genre, Audience, and Purpose

Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer occupies an unusual place within the landscape of late medieval travel writing because it blends elements of pilgrimage narrative, diplomatic report, and covert reconnaissance. Broquière composed his account upon returning to Burgundy, and both the prologue and internal references indicate that Philip requested a written record of the journey.11 The manuscript tradition supports its circulation within an elite environment rather than among wider devotional audiences who read standard pilgrimage narratives. This context shapes how the text should be understood, since it reflects the concerns of a princely court evaluating the feasibility of military expansion rather than the personal reflections of an individual traveler.

The work draws on familiar conventions of medieval travel literature, including descriptions of routes, religious sites, and interactions with local populations. Yet its content diverges from most Western pilgrimage accounts of the period. Broquière regularly comments on political structures, military organization, and economic conditions in regions under Ottoman and Mamluk control.12 His attention to infrastructure and the movement of goods shows how he adapted the genre to meet the expectations of Burgundy’s ruling circle. His narrative choices reveal the degree to which the court valued information that could be integrated into long-term strategic planning.

A comparison with other fifteenth century travel narratives highlights the hybrid nature of Broquière’s text. Works by de’ Conti and Tafur contain detailed observations, but their purposes remain tied to personal experience and the representation of marvels.13 Broquière’s account differs by emphasizing analysis over wonder. He describes clothing, customs, and local governance not to satisfy curiosity but to convey practical lessons about diplomacy, security, and travel through contested territories. This orientation toward utility distinguishes the Voyage from the broader literary tradition of late medieval travel.

The linguistic and stylistic features of the text also reveal its intended audience. Broquière wrote in a clear Burgundian French suitable for courtly readers and for advisors who would assess the political implications of his material.14 His use of precise geographic references and careful descriptions of meetings with regional officials underscores the technical quality of the work. The result is a narrative shaped by the dual goals of recounting a personal journey and providing a structured report that could assist Philip the Good in evaluating the prospects of a renewed crusading campaign.

Observations of the Levant: Political Structures, Customs, and Cross-Cultural Contact

Broquière’s descriptions of the Eastern Mediterranean offer a detailed view of political authority and administrative organization in the regions he visited. His account reflects an awareness of the shifting balance of power between local rulers and emerging imperial forces. He traveled through territories governed by the Mamluk Sultanate and the Ottoman Empire, observing officials whose authority rested on efficient systems of taxation, justice, and military oversight.15 These observations allowed him to analyze the mechanisms by which these states maintained control over diverse populations. His attention to political structures reveals a traveler engaged in assessing the stability and capacity of the powers that Burgundy viewed as potential adversaries.

His encounters in the Ottoman domains provided some of the most revealing insights. Broquière noted the discipline and mobility of Ottoman cavalry units, as well as the administrative coherence of the regions he passed through.16 He recorded the presence of fortified towns, organized supply networks, and officials responsible for supervising the movement of travelers. These elements demonstrated that the Ottoman state possessed the logistical resources necessary to support sustained military action. His detailed account offers a perspective on the strengths that would later enable the empire to expand across southeastern Europe. The emphasis on road conditions and transport routes indicates that he understood how infrastructure influenced military and commercial mobility.

Broquière’s experiences in Mamluk territory were shaped by the bureaucratic culture of the Levant. He noted the presence of well-established caravan routes linking Syrian cities with the interior.17 His observations of marketplaces, taxation practices, and administrative offices reveal an economy integrated through long-distance trade. The Mamluk state relied on systems of regulation that shaped interactions among merchants, travelers, and local officials. These administrative structures underscored the importance of commerce and communication across the region. Broquière’s descriptions provide historians with valuable information about the functioning of urban and rural communities under Mamluk rule.

Encounters with local populations formed a significant part of Broquière’s narrative. He interacted with guides, merchants, and soldiers who provided information about territorial boundaries, religious practices, and regional customs.18 These interactions often occurred in environments where he adopted local dress to avoid drawing attention. His ability to move through contested spaces depended on cooperation from individuals whose knowledge of the landscape allowed him to navigate areas that could have presented considerable danger. These exchanges suggest that cross-cultural contact was not limited to formal diplomacy but also occurred in daily situations shaped by mutual necessity.

Broquière’s narrative also offers insight into the religious landscape of the Levant. He visited Christian, Muslim, and Jewish communities, observing the social and legal arrangements that governed their relationships.19 His attention to religious practices reflects the diversity of the region and the ways in which communities coexisted within shared urban spaces. His remarks show an awareness of the tensions that occasionally arose among groups, yet he also noted instances of cooperation and mutual accommodation. His account helps to illustrate how religious identity shaped social interactions without entirely defining them.

The practical details that Broquière recorded contributed to his broader assessment of the political and economic conditions in the Eastern Mediterranean. He described roads, bridges, harbor facilities, and traveling conditions that influenced the movement of troops and goods.20 His observations reveal how he evaluated the logistical challenges that would confront any Western force attempting to operate in the region. The combination of political analysis and practical detail demonstrates how travel functioned as a means of acquiring strategic knowledge. His narrative offers a comprehensive view of the region as it appeared to a Western observer trained to assess conditions relevant to military planning.

Broquière as Spy: Intelligence, Military Assessment, and Strategic Commentary

Broquière’s journey increasingly took the form of a reconnaissance mission as he traveled deeper into Ottoman and Mamluk territories. While the framework of pilgrimage provided an initial justification for the trip, his account reveals a continuous effort to gather intelligence relevant to Burgundian military planning. He examined the condition of roads, the strength of fortifications, and the administrative structures that regulated movement across borders.21 These observations indicate that he understood the significance of infrastructure for any military operation that Philip might contemplate. His emphasis on practical detail reflects a traveler trained to assess the feasibility of campaigns in regions dominated by rival powers.

Descriptions of Ottoman military capabilities form a substantial part of Broquière’s strategic commentary. He recognized the discipline and mobility of Ottoman cavalry units, noting their ability to move rapidly across varied terrain.22 He also observed the centralization of authority under the Ottoman sultans, which allowed for coordinated military responses. His remarks on the use of local officials to supervise travel and protect routes reveal the administrative mechanisms that supported the expansion of Ottoman power. Such assessments provide historians with insight into how Western observers interpreted the strengths of a rising empire. His evaluation did not rely on rumor but on direct encounters that demonstrated the organizational efficiency of Ottoman rule.

Broquière also paid attention to the political relationships that shaped the region. He commented on alliances, feuds, and diplomatic tensions among local rulers whose decisions influenced the stability of borderlands.23 His observations reflect a world in which allegiance could shift rapidly, creating both opportunities and dangers for foreign travelers. By recording these dynamics, he provided Philip with a clearer understanding of how internal rivalries might affect the likelihood of Western intervention. His analysis demonstrates that intelligence gathering involved not only the study of military structures but also the interpretation of political conditions that could alter the outcome of campaigns.

The difficulties of travel in contested territories sharpened Broquière’s understanding of the challenges that Western forces would confront. He noted the hazards posed by irregular troops, bandit groups, and local militias whose loyalties varied depending on circumstance.24 His ability to navigate these environments often depended on blending into local society by adopting regional clothing and customs. These tactics allowed him to move more freely and acquire information that could not have been obtained openly. His experiences underscore the value of mobility and adaptability in regions where the presence of foreign travelers attracted attention. He recognized that successful campaigns required detailed knowledge of local conditions that could only be acquired through firsthand experience.

Broquière’s reflections on the feasibility of a crusade reveal the limits of Burgundian aspirations. Although he identified potential vulnerabilities in the territories he crossed, he also noted the strength of the political and military systems that dominated them.25 His strategic assessments implied that any Western force would require careful planning, substantial resources, and reliable alliances to succeed. These conclusions suggest that his intelligence gathering served not only to encourage crusading plans but also to temper them with practical considerations. His narrative provides a rare example of a fifteenth century courtier who approached the idea of crusade through empirical observation rather than through idealized visions of warfare.

The Return Journey and European Reception

Broquière’s return from the Levant took him across regions marked by political instability and territorial competition. His path through Anatolia and the Balkans exposed him to the complexities of Ottoman rule as it advanced deeper into southeastern Europe.26 He encountered administrative practices that demonstrated how the Ottomans integrated conquered territories into their expanding state. These experiences shaped the final sections of his narrative, where he reflected on the logistical and strategic challenges that any Western army would face when attempting to march through regions characterized by defensible terrain and centralized authority. His observations reveal an awareness of the obstacles posed by both natural geography and organized political control.

Broquière’s reflections on the feasibility of a crusading expedition intensified as he neared Western Europe. He considered the difficulties of transporting troops, maintaining supply lines, and securing reliable allies.27 He evaluated not only the immediate dangers presented by Ottoman military structures but also the larger diplomatic context in which Christian powers pursued their interests. His remarks show a traveler who remained committed to providing accurate information for the Burgundian court while acknowledging the limitations of Western military capacity. These assessments highlight the tension between chivalric ideals and the political realities of the fifteenth century Mediterranean world.

The European reception of Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer reveals its importance within a courtly environment that valued practical knowledge as well as narrative craftsmanship. The manuscript circulated primarily among Burgundian elites who understood the significance of Broquière’s observations for Philip’s policies.28 Although Philip never launched a crusade based on the information Broquière provided, the text influenced discussions about the future of crusading and the role Burgundy might play in resisting Ottoman expansion. Its blend of personal experience and political analysis made it a compelling contribution to the intellectual culture of a court that combined ceremonial display with strategic ambition.

Over time the work gained broader significance as historians used it to reconstruct the conditions of the Eastern Mediterranean in the years preceding the fall of Constantinople. Broquière’s careful descriptions of roads, fortifications, administrative practices, and cross-cultural interactions have provided scholars with insights into a transitional period in Mediterranean history.29 The text continues to serve as a valuable source for understanding how late medieval Europeans interpreted the political transformations unfolding across the region. Its preservation within the Burgundian tradition and subsequent scholarly editions ensure that Broquière’s observations remain central to the study of late medieval travel and crusading ideology.

Conclusion: Travel Writing, Power, and the Late Medieval Imagination

Broquière’s Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer stands as a unique record of the political and military conditions of the fifteenth century Eastern Mediterranean. His narrative combines personal experience with an acute awareness of the geopolitical tensions that shaped the region.30 It reveals how a Western courtier, trained within the cultural and administrative environment of Burgundy, interpreted the structures of authority and the forms of mobility that defined Ottoman and Mamluk territories. These observations offer more than a record of travel. They provide insight into how Europeans understood a world in which shifting power dynamics had profound consequences for Western ambitions.

Broquière’s account also illustrates the changing nature of crusading thought during the later Middle Ages. His narrative does not rely on the triumphal language that characterized earlier crusading literature.31 Instead, he approached the prospect of renewed military action with caution, assessing the strengths and vulnerabilities of regional powers based on direct experience. His reflections indicate that successful intervention required careful planning, reliable alliances, and significant logistical coordination. These conclusions highlight a pragmatic approach to crusading that diverged from older ideals rooted in religious zeal and chivalric rhetoric.

The work’s reception in the Burgundian court demonstrates how information gathered through travel could be integrated into political decision making. Philip valued Broquière’s account for the intelligence it provided about regions that were central to his ambitions.32 Although no crusade emerged from this material, the text influenced internal discussions about the feasibility of military action and the role Burgundy might play within broader European politics. Its combination of narrative detail and strategic insight made it an important contribution to the intellectual life of a court that sought to balance ceremonial grandeur with practical governance.

Modern scholarship continues to rely on Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer as a source for understanding the Eastern Mediterranean in the years before the fall of Constantinople. Broquière’s careful descriptions of infrastructure, administrative systems, and cross-cultural interactions provide historians with essential evidence for reconstructing political and social realities.33 His narrative remains a testament to the ways in which travel writing shaped European perceptions of distant regions and how such texts could serve both personal and political purposes. His journey stands as one of the final attempts to imagine a viable crusade in a world transformed by new centers of power.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Richard Vaughan, Philip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy (London: Longman, 1970), 210–215.

- Bertrandon de la Broquière, Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer, ed. Charles Schefer (Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1892), xxiii–xxviii.

- Bertrandon de la Broquière, The Travels of Bertrandon de la Brocquière to Palestine, and His Return from Jerusalem Overland to France, trans. Galen Brokaw and Steven J. Williams (London and New York: Routledge, 2019), 3–7.

- Malcolm Barber, The Crusader States (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 291–295.

- Norman Housley, The Later Crusades, 1274–1580: From Lyons to Alcazar (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 98–103.

- Vaughan, Philip the Good, 210–218.

- Christopher Tyerman, The Invention of the Crusades (London: Macmillan, 1998), 134–138.

- Santamaria, Jean-Baptiste, “Secrets, Diplomatics, and Spies in Late Medieval France and in the Burgundian State: Parallel Practices and Undercover Operations,” in Beyond Ambassadors: Consuls, Missionaries, and Spies in Premodern Diplomacy, edited by Maurits A. Ebben and Louis Sicking (Leiden: Brill, 2020): 159-184.

- P. M. Holt, The Age of the Crusades: The Near East from the Eleventh Century to 1517 (London: Longman, 1986), 154–160.

- Housley, The Later Crusades, 1274–1580, 97–103.

- Broquière, The Travels of Bertrandon de la Brocquière to Palestine, and His Return from Jerusalem Overland to France, 1–4.

- Broquière, Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer, xxiii–xxx.

- Suzanne Conklin Akbari, Idols in the East: European Representations of Islam and the Orient, 1100–1450 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009), 245–252.

- Malcolm Letts, introduction to The Travels of Leo of Rozmital, ed. Letts (London: Hakluyt Society, 1957), xvi–xxi.

- P. M. Holt, The Age of the Crusades, 154–160.

- Halil İnalcık, The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age, 1300–1600 (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1973), 23–29.

- Holt, The Age of the Crusades, 161–166.

- Broquière, Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer, xxv–xxviii.

- Barber, The Crusader States, 291–295.

- Broquière, The Travels of Bertrandon de la Brocquière to Palestine, and His Return from Jerusalem Overland to France, 45–52.

- Housley, The Later Crusades, 1274–1580, 97–103.

- Halil İnalcık, The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age, 1300–1600 (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1973), 23–29.

- Holt, The Age of the Crusades, 154–166.

- Broquière, Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer, xxv–xxviii.

- Vaughan, Philip the Good, 214–218.

- İnalcık, The Ottoman Empire, 29–34.

- Housley, The Later Crusades, 1274–1580, 103–108.

- Vaughan, Philip the Good, 215–219.

- Barber, The Crusader States, 295–300.

- Broquière, The Travels of Bertrandon de la Brocquière to Palestine, and His Return from Jerusalem Overland to France, 5–9.

- Christopher Tyerman, God’s War: A New History of the Crusades (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006), 851–856.

- Vaughan, Philip the Good, 215–219.

- Barber, The Crusader States, 295–300.

Bibliography

- Akbari, Suzanne Conklin. Idols in the East: European Representations of Islam and the Orient, 1100–1450. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009.

- Barber, Malcolm. The Crusader States. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012.

- Broquière, Bertrandon de la. Le Voyage d’Outre-Mer. Edited by Charles Schefer. Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1892.

- —-. The Travels of Bertrandon de la Brocquière to Palestine, and His Return from Jerusalem Overland to France. Translated by Galen Brokaw and Steven J. Williams. London and New York: Routledge, 2019.

- Santamaria, Jean-Baptiste. “Secrets, Diplomatics, and Spies in Late Medieval France and in the Burgundian State: Parallel Practices and Undercover Operations.” In Beyond Ambassadors: Consuls, Missionaries, and Spies in Premodern Diplomacy, edited by Maurits A. Ebben and Louis Sicking. Leiden: Brill, 2020, 159-184.

- Holt, P. M. The Age of the Crusades: The Near East from the Eleventh Century to 1517. London: Longman, 1986.

- Housley, Norman. The Later Crusades, 1274–1580: From Lyons to Alcazar. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- İnalcık, Halil. The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age, 1300–1600. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1973.

- Letts, Malcolm. Introduction to The Travels of Leo of Rozmital. Edited by Malcolm Letts. London: Hakluyt Society, 1957.

- Tyerman, Christopher. God’s War: A New History of the Crusades. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- —-. The Invention of the Crusades. London: Macmillan, 1998.

- Vaughan, Richard. Philip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy. London: Longman, 1970.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.27.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.