The Gestapo’s targeting of immigrants reveals how racial ideology and administrative authority converged to create one of the most expansive surveillance systems in modern history.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Immigrant as an Enemy of the Nazi State

The rise of the Nazi regime transformed Germany’s immigrant communities into targets of a political system intent on producing a homogenous national body. Immigrants were not only marked as culturally foreign. They occupied the position of racial and political threats within a state that reorganized law and policing around biological hierarchies. Their vulnerability sharpened as the Gestapo consolidated authority and began to treat residency without “Aryan” descent as a problem of internal security. This framing allowed the secret police to convert immigrants into the earliest test subjects of extrajudicial power, long before the wartime deportation system reached its full scale.1

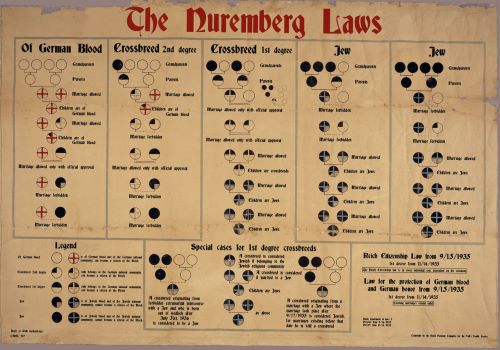

The destruction of legal boundaries was central to this process. Nazi racial theory fed directly into the rewriting of citizenship statutes and police prerogatives. The Nuremberg Laws stripped Jewish immigrants of basic civil protections and reclassified national belonging as a matter of blood.2 The same years saw the refinement of “protective custody,” an administrative category that enabled the Gestapo to detain individuals indefinitely without judicial oversight.3 These measures created the legal foundation on which violence against immigrant groups could expand with few internal restraints. The result was a policing system that treated nationality, ethnicity, and political reliability as mutually reinforcing categories.

As the regime stabilized, the Gestapo used this structure to fuse surveillance with racial policy. Reports of foreign associations, personal relationships, or perceived disloyalty routinely triggered investigations.4 Complaint letters from neighbors and employers transformed local prejudice into mechanisms of state power. In practice, the immigrant became a figure whose fate hinged on the judgments of police officers and the allegations of ordinary residents. This dynamic magnified the reach of the Gestapo and made social collaboration an integral part of political repression.

By the eve of the Second World War, these developments had positioned immigrants at the center of the Nazi state’s experiments with coercive authority. The 1938 expulsion of Polish Jews and the expanding network of detention sites showed how policing could be transformed into a system of mass removal.5 When war began, the Gestapo possessed both the ideological framework and the administrative apparatus required to turn immigration status into a basis for deportation. In this environment, the immigrant community became one of the earliest groups to experience the convergence of racial theory, legal manipulation, and secret policing that would ultimately define the Third Reich’s machinery of persecution.

Ideological and Legal Frameworks for the Persecution of Immigrants

The persecution of immigrants in Nazi Germany grew from a legal order that fused racial theory with administrative power. From the outset, the regime reimagined citizenship and belonging through biological criteria, identifying groups considered foreign as threats to national integrity. The Reich Citizenship Law of 1935 divided the population into those who belonged to the national community and those excluded from it on racial grounds. Jewish immigrants and long-settled Jewish residents were reduced to the status of subjects without political rights. These legal redefinitions provided the backdrop for the Gestapo to craft a policing strategy in which immigration status, race, and national loyalty were treated as interconnected questions of internal security.6

The transformation of policing followed quickly. The creation of protective custody, which originated during the consolidation of Hitler’s regime, permitted the Gestapo to seize individuals who were believed to threaten the state without any judicial approval. This administrative device grew in scope during the mid-1930s as the secret police formalized its authority to detain people indefinitely. Protective custody orders were issued against Jewish immigrants, political refugees, and foreign workers on the basis of perceived unreliability rather than criminal acts.7 The practice helped construct a policing culture in which the Gestapo operated above the judicial system and treated ethnicity and nationality as markers of potential danger.

The ideological foundation for such policing drew from the broader racial program articulated by the Nazi leadership. Influential figures in the regime promoted theories that cast immigrants as biologically incompatible with the German national body. Nazi administrators interpreted social problems through racial categories and presented enforcement actions as necessary for the health of the nation.8 In this environment, the immigrant became a political figure whose identity signaled vulnerability. Legal discrimination, surveillance, and detention were justified through claims that only decisive state measures could protect Germany from internal decay.

The legal and ideological developments reshaped the boundaries of everyday life. Jewish immigrants lost property protections through decrees that required the registration and forced sale of assets.9 Foreign nationals from eastern Europe faced regulations that restricted access to employment, public space, and housing. These measures served not only to isolate immigrants but also to strengthen the Gestapo’s authority by supplying new categories of violations that triggered police intervention. The range of punishable acts widened, and ordinary patterns of residence or work could become grounds for investigation.

Some scholars have argued that the Gestapo was not the sole architect of these policies, noting that local police forces and administrative offices often initiated actions that targeted immigrants. This perspective emphasizes the involvement of multiple institutions and the decentralized nature of repression. Ideological signals coming from the top gave the Gestapo a unique capacity to align policing with racial goals.10 The combination of legal transformation and ideological direction allowed the Gestapo to absorb and coordinate these broader institutional activities. By the late 1930s, the secret police had become the central mechanism for implementing the racial and national categories that governed life in the Third Reich.

The Polenaktion and the Early Mass Expulsions of Polish Jews

The expulsion of Polish Jews in October 1938, known as the Polenaktion, was one of the earliest large-scale actions in which the Gestapo transformed its policing powers into a mechanism of mass removal. The origins of the operation lay in a diplomatic conflict between Germany and Poland over citizenship revocations. In March 1938, Poland enacted legislation that allowed authorities to strip Polish citizens abroad of their nationality if they failed to renew their passports.11 German officials feared that tens of thousands of Polish Jews living within the Reich might become stateless and therefore impossible to deport. The Gestapo used this development to justify a sudden, coordinated sweep that forced approximately seventeen thousand individuals across the border into improvised camps along the frontier.12 These expulsions revealed how immigration status and racial categorization could be combined to produce rapid and violent administrative action.

The operation displayed the Gestapo’s capacity for logistical coordination. Local police precincts and Gestapo field offices received urgent orders instructing them to identify, arrest, and transport Polish Jews within a single night. Many of those targeted had lived in Germany for decades, with established families and businesses, yet were treated as foreigners whose presence threatened national security.13 Communication between police stations, transportation officials, and border authorities created a chain of enforcement that moved people with little time for preparation or appeal. The expulsions demonstrated the organizational coherence that would characterize later deportation efforts, although the Polenaktion remained distinct in its abruptness and public visibility.

The experience of the victims underscored the precariousness of immigrant life under Nazi rule. Accounts preserved in contemporary newspaper coverage and later investigations describe how families were seized at dawn, permitted to gather only a few belongings, and transported to border zones where Polish authorities initially refused entry.14 The result was a humanitarian crisis in which thousands of expelled persons remained stranded in makeshift shelters. These borderland conditions foreshadowed the ghettoization policies that emerged during the war, highlighting how racial ideology and state power could converge to produce liminal spaces outside legal protections.

Interpretations of the Polenaktion have emphasized different causal factors. Some historians point to the diplomatic motives behind the operation, arguing that Germany sought to preempt Poland’s citizenship restrictions and shield itself from the administrative burden of stateless residents. Historians have stressed the racial dimensions of the decision, noting that the Gestapo seized the opportunity to remove a population viewed as incompatible with the national community.15 The convergence of foreign policy concerns and racial strategy produced a moment in which immigration status made an entire group immediately expendable. The Polenaktion thus marked a significant stage in the escalation of state violence, revealing how the Gestapo could mobilize administrative resources to redefine the presence of immigrants as an urgent threat.

Anonymous Denunciations and the Social Collaboration Behind Immigrant Persecution

The Gestapo’s ability to target immigrants depended not only on centralized directives but also on the participation of ordinary residents who supplied information to local police offices. Anonymous denunciations became a crucial component of the secret police system by the mid-1930s, shaping investigations that disproportionately affected immigrants, foreign workers, and Jewish refugees. Analysis of case files from Bavaria demonstrates that a large proportion of Gestapo activity originated in reports submitted by civilians rather than proactive police surveillance.16 These denunciations often focused on personal disputes, economic rivalries, or prejudicial assumptions about foreign communities, and the Gestapo treated them as credible leads. Immigrants thus lived at the intersection of state power and public hostility, where allegations carried significant consequences.

The structure of the complaint system granted the Gestapo wide discretion in determining how to respond to denunciations. Many immigrants faced investigation for violations that would ordinarily have had no public significance, such as speaking foreign languages at work or maintaining social ties across borders. Neighbors framed such behaviors as threats to national security and presented them as evidence of disloyalty or racial difference.17 The Gestapo interpreted these accusations within an ideological framework that viewed immigrants as potential saboteurs or cultural contaminants. Investigations could begin with a single letter or telephone call, opening the door to interrogation and detention, often without concrete evidence.

The role of denunciations intensified as anti-Jewish policies became more radical. Jewish immigrants had already been rendered politically vulnerable through the Nuremberg Laws, and public hostility magnified this vulnerability. Individuals who were newly defined as noncitizens faced a higher likelihood of being denounced for imagined violations.18 Local rivalries and economic disputes frequently motivated these reports. The Gestapo, however, rarely scrutinized the motives of informants. Instead, the agency incorporated denunciations into its files as indicators of communal suspicion, which justified further action. This process allowed ordinary residents to harness state power against immigrant neighbors with devastating consequences.

Archival records show that denunciations often carried the weight of racial logic even when the allegations themselves were vague. Case files from the Würzburg and Munich Gestapo offices include complaints accusing immigrants of undermining public morale, hoarding goods, or expressing unpatriotic sentiments.19 The evidence behind these claims was often thin, but the racialized framing of the immigrant as an outsider lent credibility to the accusations. Gestapo officers used such reports to justify surveillance visits, house searches, and the issuance of protective custody orders. The complaint system thus provided a steady influx of material that reinforced the agency’s ideological assumptions and expanded the reach of its authority.

Historians have debated the extent to which denunciations represented genuine support for Nazi racial policy versus attempts by individuals to settle personal disputes. Everyday Germans often acted out of opportunism or fear rather than ideological conviction.20 Yet these motives did not alter the outcome for immigrants, who remained the primary victims of a social environment in which suspicion was easily converted into state violence. Regardless of intention, denunciations strengthened the Gestapo’s policing structure by supplying raw information that aligned with its expectations. The immigrant became a figure whose vulnerability grew in proportion to the willingness of the public to collaborate. This dynamic created a climate in which social prejudice and administrative power worked in parallel, tightening the grip of the political police over communities defined as foreign.

Arbitrary Arrests, Interrogations, and Schutzhaft

The Gestapo’s authority to arrest immigrants at will rested on the administrative category of protective custody, which allowed detention without judicial review. Originally developed during the suppression of political opponents in the early years of Nazi rule, protective custody evolved into a flexible instrument that the Gestapo used to classify entire groups as potential threats. Immigrants were especially vulnerable because their residency status, foreign origins, and perceived cultural distance made them easy to portray as security risks. Protective custody orders required no concrete evidence or formal indictment. The mere suspicion of political unreliability or racial undesirability could justify confinement.21 Once placed under this designation, immigrants lost access to legal protections, and the Gestapo could transfer them to concentration camps indefinitely.

The interrogation process deepened this vulnerability. Gestapo methods relied on intense psychological pressure, prolonged questioning, and physical coercion. Interrogations were designed to extract confessions rather than to establish factual accuracy.22 Immigrants were frequently questioned about their contacts abroad, political affiliations, languages spoken, and community ties. This approach reflected the agency’s preconceptions about foreign groups and its belief that immigrants served as conduits for espionage or subversion. The resulting interviews often produced statements that investigators interpreted as confirmations of ideological suspicion, reinforcing the cycle of arrest and detention.

For many immigrants, the absence of judicial oversight meant that the path to detention was abrupt and difficult to navigate. Protective custody orders bypassed courts and denied detainees the right to legal representation.23 Families often learned of arrests only after the individual had disappeared into a local jail or transit camp. Foreign residents who attempted to petition for release found that consular intervention was ineffective, particularly after 1938, when diplomatic protections for Jewish immigrants deteriorated. Even immigrants who held valid residency permits could be detained for minor infractions or for activities interpreted as expressions of non-German identity. The legal environment thus created a situation in which immigrants existed in a zone of precarity defined by administrative power.

Archival evidence from regional Gestapo offices shows how arbitrary arrests of immigrants became routine during the late 1930s. Case files include examples of foreign workers detained for curfew violations, alleged political remarks, or contact with individuals already under investigation.24 These arrests were rarely isolated decisions. Gestapo officials often placed immigrants into custody preemptively, assuming that foreign origin signaled ideological unreliability. The combination of suspicion, racial policy, and bureaucratic efficiency meant that the threshold for detention steadily decreased. Arrests did not require warrants, and the internal paperwork justified its conclusions by invoking general security concerns rather than specific violations.

Arbitrary arrests (schutzhaft) also played a practical role in the expansion of the concentration camp system. As the Gestapo accumulated increasing numbers of detainees, local prisons and police stations struggled to accommodate them. The growth of the camp system was closely tied to the rising use of protective custody orders issued by the secret police.25 Immigrants, especially Jewish refugees and eastern European workers, represented a significant portion of those transferred from police custody to the early camps. The movement of detainees from interrogation cells to camps created a pipeline that operated with minimal administrative friction and reflected the broader shift toward racialized detention as a tool of governance.

Historians have debated whether the Gestapo’s actions reflected a coherent strategy or a pattern of improvised responses to perceived threats. Some scholars argue that arrests were inconsistent and shaped by local conditions. Others emphasize the ideological clarity behind these actions, noting that the targeting of immigrants aligned directly with the regime’s racial worldview.26 Regardless of interpretation, the practical outcome remained consistent. Immigrants lived within a legal structure that treated them as inherently suspect and allowed the state to detain them without restraint. This environment produced a daily reality in which ordinary behaviors could attract police attention, and administrative categories carried the weight of irrevocable punishment.

Coordination of Deportations: From Policing to Genocidal Infrastructure

The Gestapo’s role in coordinating deportations evolved rapidly after the war began, transforming the agency from a domestic security force into a central component of the machinery that moved millions toward ghettos and extermination centers. Early wartime deportations targeted immigrant communities that the state had already marked as foreign or racially incompatible. Jewish immigrants were among the first to be placed on transport lists because their legal status had been eroded through successive decrees that stripped them of citizenship and economic rights. The Gestapo administered these measures through the issuance of transport orders, regional roundups, and collaboration with railway officials. This cooperation between police offices and transportation bureaus laid the groundwork for the far larger deportation operations that followed.27 The bureaucratic coordination of arrests, assembly points, and rail schedules established a pattern that linked secret policing directly to mass displacement.

The integration of the Gestapo into the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA) further institutionalized its role in these operations. Under the RSHA’s structure, the Gestapo worked alongside the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) and criminal police in implementing the broader racial policies articulated by the regime. Saul Friedländer documents how these agencies cooperated in identifying Jewish immigrants and other foreign nationals for deportation, using census data, residence permits, and community records to construct lists of individuals targeted for removal.28 Deportation directives circulated between Berlin and regional offices, instructing local police to assemble detainees at railway stations where SS personnel oversaw the transports. Immigrants who attempted to appeal their inclusion on the lists found that the combined authority of the RSHA and the Gestapo rendered such efforts futile.

The deportation process relied on extensive documentation generated at multiple administrative levels. Archival materials from ghettos such as Łódź include transport manifests listing names, ages, occupations, and prior addresses of deportees.29 These records reveal the systematic nature of the process and show how immigrant communities were incorporated into the broader framework of ghettoization. Gestapo officers in occupied territories coordinated with local administrators to ensure that individuals classified as foreign or racially undesirable were included in the transports. The existence of these lists underscores the central role that bureaucracy played in the construction of genocidal policy and helps trace the path that individual immigrants followed from arrest to deportation.

As deportations expanded, the Gestapo’s involvement grew more direct. In many regions, the agency supervised the assembly of deportees in municipal buildings, sports halls, or temporary camps prior to their transfer. Reports preserved in regional archives describe searches for contraband, confiscation of property, and the separation of families during processing.30 Deportees were moved under guard to trains that carried them to ghettos or transit camps in Poland. The presence of Gestapo personnel at each stage ensured that the process operated with minimal disruption and that any resistance was swiftly suppressed. The immigrant’s experience of deportation was therefore shaped by a system in which surveillance, arrest, and transportation formed an uninterrupted chain of state violence.

Historians have debated the extent to which the Gestapo acted as the primary engine of deportation or functioned within a broader network of institutions. Although multiple agencies contributed to the process, the Gestapo played a decisive role in determining who would be deported and in carrying out the necessary arrests.31 Other scholars have emphasized the logistical importance of railway officials, local administrators, and the SS. Yet these perspectives converge in recognizing that the Gestapo served as the nexus between racial policy and its physical implementation. For immigrants, this meant that deportation was not a sudden rupture but the culmination of a policing regime that had defined them as outsiders from the beginning. The transition from surveillance to removal represented the logical extension of a system that fused ideology with administrative power.

Forced Laborers and the Expansion of Gestapo Surveillance

The rapid influx of millions of foreign forced laborers during the Second World War expanded the Gestapo’s authority over new and diverse populations. Poles, Soviets, and other eastern European workers were brought to Germany under coercive conditions and placed within a racial hierarchy that defined them as inferior. Their status as non-Germans created a parallel system of surveillance in which the Gestapo exercised extensive control over movement, employment, and daily life. Forced laborers lived under regulations that restricted their access to public facilities, imposed curfews, and mandated visible identification marks.32 These rules justified continuous monitoring and allowed the Gestapo to intervene whenever local officials deemed behavior suspicious or racially problematic.

The policing of forced laborers relied on close cooperation between industrial managers, local administrators, and secret police officers. Factories were required to report infractions ranging from tardiness to alleged political statements.33 Many such reports used racialized language, portraying eastern European workers as unreliable or prone to subversion. The Gestapo interpreted these claims as indicators of ideological risk, and investigations often led to arrest or transfer to punishment camps. The dynamic mirrored the treatment of immigrants inside the Reich before the war. In both contexts, the state treated foreign identity as a category that required constant supervision and swift punitive action.

Punitive measures escalated as the labor system expanded. Workers accused of sabotage, theft, or personal misconduct were often subjected to public beatings, confinement in labor education camps, or execution.34 Archival records from German factories and occupied cities describe how Gestapo officers imposed discipline through fear, using exemplary punishments to deter resistance. These actions were rarely supported by evidence. Instead, they reflected the ideological assumptions embedded in Nazi racial policy, which viewed eastern European laborers as inherently dangerous. This environment made it difficult for forced workers to seek redress, since complaints were interpreted as signs of insubordination rather than legitimate grievances.

Despite the oppressive conditions, some laborers attempted to negotiate their position within the system. Mark Spoerer notes that certain workers formed informal networks to obtain better food, communicate with families, or evade the harshest forms of discipline.35 These networks, however, existed within strict limits. Gestapo surveillance extended into barracks, workplaces, and transportation routes, leaving little room for sustained resistance. When authorities detected collective defiance or suspected sabotage, reprisals were swift and severe. The structural imbalance of power meant that even small attempts at autonomy carried significant risk.

The policing of forced laborers reinforced the broader relationship between racial ideology and administrative control. For the Gestapo, foreign workers represented both an economic resource and a potential source of instability. Their treatment reveals how the secret police viewed foreign identity as a problem that required systematic oversight. The agency’s involvement transformed labor sites into extensions of the racial state, where punishment, coercion, and surveillance operated in tandem.36 Forced labor thus became another arena in which the Gestapo’s approach to immigrants and foreigners shaped the everyday experience of millions. The labor system did not stand apart from other mechanisms of persecution but functioned as an integral component of a state that defined its power through the management of racial difference.

Conclusion: Immigration, Racial Power, and the Architecture of State Terror

The Gestapo’s targeting of immigrants reveals how racial ideology and administrative authority converged to create one of the most expansive surveillance systems in modern history. From the earliest years of Nazi rule, immigrant communities were positioned at the margins of legal protection, defined not by specific actions but by their perceived incompatibility with the national body. The shifts in citizenship law, the development of protective custody, and the growth of denunciation networks produced an environment in which immigrants could be arrested, interrogated, and deported with little oversight. Scholars have shown that these policies began long before the outbreak of war and laid the foundations for later genocidal practices.37 The immigrant thus became a central figure in the evolution of a state that fused ideological ambition with bureaucratic precision.

The wartime escalation of deportations further demonstrated how the Gestapo turned policing practices into instruments of mass violence. Immigrants, refugees, and foreign workers were swept into a deportation system that relied on meticulous documentation, coordination between agencies, and the mobilization of transportation networks. The incorporation of the Gestapo into the Reich Main Security Office enabled the agency to merge racial policy with logistical execution, transforming local arrests into part of a continent wide project of displacement and extermination.38 The relentless expansion of deportation lists and transport operations illustrated how administrative structures could be adapted to genocidal ends when no legal constraints remained.

The treatment of forced laborers added another dimension to this pattern. Millions of foreign workers experienced daily life under regulations shaped by racial ideology and enforced by secret police intervention. The Gestapo’s authority extended into factories, barracks, and workplaces, making surveillance a constant feature of labor exploitation.39 These conditions were not accidental byproducts of wartime necessity but deliberate policies that transformed foreign origin into a justification for punishment and control. The immigrant and the forced laborer faced different circumstances, yet both were subjected to a system that marked foreign identity as an inherent threat.

The convergence of these practices created a political environment in which the boundaries between policing, punishment, and mass murder were dissolved. The Gestapo’s treatment of immigrants demonstrates how a state can redesign its institutions to implement racial policy through everyday acts of administration. This history underscores the danger of legal structures that divorce power from judicial scrutiny and define entire groups as outside the protection of the law. The experiences of immigrants in Nazi Germany speak not only to the past but to the broader question of how states use bureaucracy to construct categories of exclusion. Understanding these processes remains essential for recognizing how racialized governance can evolve into systematic violence when ideology and administrative authority operate without restraint.40

Appendix

Footnotes

- Nikolaus Wachsmann, KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015), 49–54.

- Reichsgesetzblatt I, 1935, pp. 1333–1334 (Nuremberg Laws, including the Reich Citizenship Law).

- Robert Gellately, Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 13–15.

- Claudia Koonz, The Nazi Conscience (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2003), 118–124.

- Saul Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume I: The Years of Persecution, 1933–1939 (New York: HarperCollins, 1997), 273–279.

- Reichsgesetzblatt I, 1935, pp. 1333–1334.

- Wachsmann, KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps, 47–55.

- Michael Burleigh, The Racial State: Germany 1933–1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 27–33.

- Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume I, 206–212.

- Koonz, The Nazi Conscience, 134–140.

- Dziennik Ustaw Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej [Polish Journal of Laws], 1938, no. 22, item 191 (Polish citizenship regulation).

- Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume I, 273–276.

- Ibid., 276–279.

- Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt, contemporary reporting, October–November 1938; also summarized in United States Holocaust Memorial Museum archival materials on the Polenaktion.

- Christopher R. Browning, The Origins of the Final Solution (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 21–25.

- Gellately, Backing Hitler, 92–110.

- Koonz, The Nazi Conscience, 118–124.

- Gellately, Backing Hitler, 110–115.

- Bavarian State Archives, Gestapo Würzburg and Gestapo Munich case files, selections referenced in Gellately, Backing Hitler, 101–107.

- Peter Fritzsche, Life and Death in the Third Reich (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2008), 58–65.

- Wachsmann, KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps, 47–55.

- Browning, The Origins of the Final Solution, 22–24.

- Gellately, Backing Hitler, 13–17.

- Bavarian State Archives, Gestapo Würzburg and Gestapo Munich case files, cited in Gellately, Backing Hitler, 101–107.

- Wachsmann, KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps, 58–66.

- Koonz, The Nazi Conscience, 134–140.

- Browning, The Origins of the Final Solution, 78–85.

- Saul Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume II: The Years of Extermination, 1939–1945 (New York: HarperCollins, 2007), 39–45.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Łódź Ghetto Archives, transport lists and administrative records.

- Regional police and Gestapo reports from occupied Poland, cited in Friedländer, Years of Extermination, 101–107.

- Wachsmann, KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps, 92–99.

- Ulrich Herbert, Hitler’s Foreign Workers: Enforced Foreign Labor in Germany under the Third Reich (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 45–52.

- Ibid., 132–139.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, forced labor documentation, including camp regulations and factory disciplinary records.

- Mark Spoerer, Zwangsarbeit unter dem Hakenkreuz: Ausländische Zivilarbeiter, Kriegsgefangene und KZ-Häftlinge in Deutschland und Österreich 1939–1945 (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 2001), 88–94.

- Herbert, Hitler’s Foreign Workers, 210–219.

- Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume I; Wachsmann, KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps.

- Browning, The Origins of the Final Solution, 78–85.

- Herbert, Hitler’s Foreign Workers, 132–139, 210–219.

- Koonz, The Nazi Conscience, 134–140.

Bibliography

- Bavarian State Archives. Gestapo Würzburg and Gestapo Munich case files. Cited in Robert Gellately, Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Browning, Christopher R. The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939–March 1942. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

- Burleigh, Michael, and Wolfgang Wippermann. The Racial State: Germany 1933–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Dziennik Ustaw Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej [Polish Journal of Laws]. 1938, no. 22, item 191.

- Friedländer, Saul. Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume I: The Years of Persecution, 1933–1939. New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

- —-. Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume II: The Years of Extermination, 1939–1945. New York: HarperCollins, 2007.

- Fritzsche, Peter. Life and Death in the Third Reich. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2008.

- Gellately, Robert. Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Herbert, Ulrich. Hitler’s Foreign Workers: Enforced Foreign Labor in Germany under the Third Reich. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt. Contemporary reporting, October–November 1938.

- Koonz, Claudia. The Nazi Conscience. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2003.

- Reichsgesetzblatt I. 1935. Citizenship legislation and related decrees.

- Spoerer, Mark. Zwangsarbeit unter dem Hakenkreuz: Ausländische Zivilarbeiter, Kriegsgefangene und KZ-Häftlinge in Deutschland und Österreich 1939–1945. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 2001.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Forced labor documentation, including camp regulations and factory disciplinary records.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Łódź Ghetto Archives, transport lists and administrative records.

- Wachsmann, Nikolaus. KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.02.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.