The life and career of Charles Dickens challenge conventional definitions of education rooted in formal schooling and credentialed expertise.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Education Outside the Classroom

Formal education has long been treated as the primary gateway to intellectual authority, social mobility, and cultural legitimacy. In nineteenth-century Britain, this assumption carried particular force, as schooling increasingly marked the boundary between respectability and marginality. Yet the Victorian period also produced figures whose intellectual formation unfolded largely outside institutional classrooms. Among them, Charles Dickens stands as one of the most striking examples. His literary authority did not emerge from sustained formal schooling but from a fragmented, improvised, and often brutal education shaped by poverty, labor, and close observation of social life.

Dickens’s early encounters with schooling were brief and unstable, repeatedly interrupted by financial insecurity. When his family collapsed into debt and his father was imprisoned, formal education gave way to child labor. This rupture did more than alter the course of his youth. It fundamentally reoriented the sources from which he learned about the world. Workplaces, streets, prisons, and offices replaced classrooms. Survival itself became a form of instruction. The knowledge acquired under these conditions was not abstract or theoretical but immediate, embodied, and morally charged.

To understand Dickens’s development as a writer and social critic, education must therefore be defined more broadly than attendance at school or mastery of classical curricula. His learning emerged through reading undertaken without supervision, skills acquired through necessity, and an acute attentiveness to human behavior across class lines. These modes of self-education cultivated an empirical understanding of Victorian society that no formal syllabus could have supplied. They also fostered a lifelong sensitivity to injustice, humiliation, and institutional cruelty, themes that recur insistently throughout his fiction and journalism.

What follows argues that Dickens’s lack of prolonged formal schooling did not represent an intellectual deficiency but rather a formative condition that shaped both his literary method and his moral vision. Educated by necessity rather than design, Dickens transformed lived experience into social knowledge. His career demonstrates how education can arise from disruption and deprivation, producing not only technical skill but a powerful capacity to interpret and critique the structures of society itself.

Early Schooling and Its Abrupt End

Before poverty reshaped his life, Dickens experienced a modest and uneven introduction to formal schooling that reflected the fragile status of his family. Born into the lower middle class, Dickens was not excluded from education by principle but by circumstance. His earliest schooling took place in Kent, where he received basic instruction in reading, writing, and arithmetic. These early experiences suggested the possibility of a conventional educational path, one consistent with the aspirations of families who hovered just above the line of destitution in early nineteenth-century England.

That path proved unsustainable. Dickens’s father’s chronic financial mismanagement repeatedly destabilized the household, forcing relocations and disrupting any sense of continuity. Schooling was treated as expendable when weighed against immediate survival. Unlike elite Victorian education, which emphasized progression and accumulation, Dickens’s early schooling was episodic and insecure. The uncertainty surrounding his education mirrored the broader vulnerability of families whose respectability depended on income streams that could vanish without warning.

The decisive rupture came when Dickens’s father was imprisoned for debt, an event that abruptly ended any remaining illusion of educational stability. At an age when many children were consolidating foundational skills, Dickens was removed from school and sent to work. This termination was not framed as temporary. It marked a structural shift in his life, replacing education as preparation for the future with labor as a condition of the present. The emotional consequences of this displacement would linger long after the material crisis passed.

Dickens did briefly return to schooling after his family’s circumstances improved, but the interruption had already altered his relationship with formal education. School no longer represented a secure or authoritative space. Instead, it appeared provisional and unreliable, subordinate to economic necessity. This early pattern of entry and exit reinforced a lifelong awareness of how easily institutional promises could collapse under social pressure, an insight that would later inform his skepticism toward systems that claimed moral authority while failing the vulnerable.

Poverty, Imprisonment, and the Collapse of Childhood

The imprisonment of Dickens’s father for debt marked a decisive rupture in his life, one that transformed economic hardship into existential upheaval. In early nineteenth-century England, debt imprisonment was both common and socially devastating. Families were not merely deprived of income but publicly marked by shame. For Dickens, this moment signaled the abrupt collapse of childhood security and the beginning of an education grounded in fear, exposure, and loss rather than guidance or care.

The Marshalsea Prison, where his father was confined, represented more than a physical space of incarceration. It functioned as a symbol of systemic cruelty, revealing how legal institutions punished poverty while preserving the dignity of wealth. Dickens was not imprisoned himself, but the consequences reached deeply into his daily life. The separation from his parents, the dispersal of his family, and the sudden demand that he contribute financially forced him into an adult role long before emotional readiness or social support could develop.

This experience reshaped Dickens’s understanding of authority and justice. The law, which purported to maintain order and fairness, appeared instead as an indifferent mechanism that intensified suffering. Education, once imagined as a ladder toward stability, vanished entirely from reach. In its place emerged a harsh lesson in social stratification. Dickens learned not from textbooks but from the visible consequences of institutional power exercised without compassion.

The psychological damage of this transition cannot be overstated. Dickens later described the period as one of profound humiliation and abandonment. Childhood, as a protected stage of moral and intellectual formation, simply ceased to exist. This loss would later surface repeatedly in his fiction, where children are often thrust into adult responsibilities by economic violence and bureaucratic neglect. His literary attention to childhood suffering was not sentimental invention but memory shaped into narrative.

Yet this collapse of childhood also produced a distinctive form of awareness. Dickens became acutely sensitive to the fragility of social standing and the ease with which respectability could disintegrate. Poverty was no longer an abstraction but a lived condition enforced by law and custom. The knowledge gained through this rupture was neither chosen nor benign, but it formed a foundational layer of his intellectual development. From this point forward, Dickens’s education would be inseparable from an ethical commitment to exposing the human cost of institutional indifference.

The Blacking Warehouse as an Unofficial Classroom

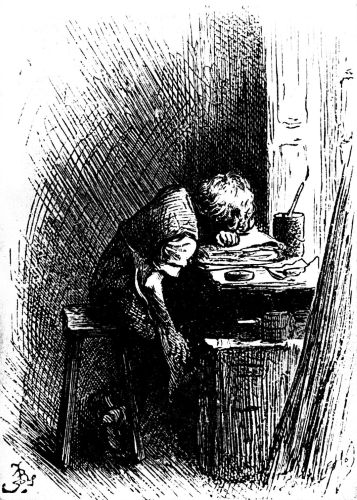

The period Dickens spent working in a blacking warehouse stands as one of the most formative episodes of his life, functioning as an education imposed by necessity rather than choice. Assigned to monotonous labor at an age when formal learning typically continued, Dickens entered a world defined by exhaustion, repetition, and social invisibility. The warehouse offered no intellectual instruction in the conventional sense, yet it exposed him daily to the mechanics of exploitation, the degradation of child labor, and the indifference of adults who benefited from such arrangements.

Within this environment, Dickens learned the lived realities of class hierarchy with an intimacy no classroom could have provided. He worked alongside other children and marginalized laborers whose futures were circumscribed by poverty and circumstance. Observation became his primary mode of learning. He absorbed the gestures, speech patterns, and quiet despair of those around him, developing an acute sensitivity to the ways economic systems reduced human beings to instruments of profit. This knowledge was experiential and cumulative, shaped through repetition and enforced proximity rather than instruction.

The emotional impact of the warehouse experience was equally instructive. Dickens later recalled feelings of shame, abandonment, and isolation, particularly the sense that he had been forgotten by those who should have protected him. These emotions did not dissipate with time. Instead, they hardened into moral awareness. The humiliation of child labor became a lens through which he interpreted broader social practices, enabling him to identify cruelty not only in overt violence but in bureaucratic neglect and normalized suffering.

What the blacking warehouse ultimately taught Dickens was not merely how poverty functioned, but how it felt. This distinction would prove crucial to his literary power. His later depictions of working-class hardship and institutional cruelty carried an authenticity rooted in memory rather than imagination. The warehouse served as an unofficial classroom where Dickens learned the emotional grammar of injustice. That education, forged under coercion, supplied him with a depth of social knowledge that would shape his writing and his enduring critique of Victorian society.

Return to School and Final Departure

After the immediate crisis of his father’s imprisonment eased, Dickens briefly returned to formal schooling, an episode that might appear, at first glance, to signal a restoration of educational normalcy. He was enrolled at Wellington House Academy in London, a private school typical of the lower-tier institutions that served families of limited means. These schools promised instruction and discipline but often delivered little more than rote learning and inadequate supervision. For Dickens, the return to school did not represent a recovery of lost childhood so much as an interlude between periods of necessity.

The quality of education at Wellington House reflected the broader deficiencies of Victorian schooling for those outside elite circles. Instruction was mechanical, intellectual curiosity discouraged, and corporal punishment common. Rather than nurturing critical thinking or moral development, such schools emphasized obedience and endurance. Dickens absorbed these conditions with the same attentiveness he had brought to the warehouse, noting how institutions that claimed to educate could instead replicate forms of domination and neglect. Formal schooling, in this context, offered no refuge from the social realities he had already encountered.

By the age of fifteen, Dickens left school permanently and entered the workforce, first as a clerk and later as a junior journalist. This departure was not framed as a failure or an interruption but as an expected transition into adulthood. Economic contribution once again took precedence over education, reinforcing the lesson that institutional learning was conditional and fragile. From this point forward, Dickens’s intellectual development would proceed without the scaffolding of formal instruction, shaped instead by work, reading, and observation.

The finality of this departure proved decisive. Having experienced both the promises and limitations of schooling, Dickens did not romanticize institutional education as an unquestioned good. Instead, he turned deliberately toward self-directed learning, cultivating knowledge through exposure to political debate, legal proceedings, and the rhythms of urban life. His education, no longer tied to classrooms, became adaptive and expansive. This shift marked the end of formal schooling but the beginning of an intellectual independence that would define his career and his authority as a commentator on Victorian society.

Self-Education Through Reading and Observation

With formal schooling behind him, Dickens entered a period of deliberate and sustained self-education shaped by reading, work, and close observation of the world around him. Deprived of institutional guidance, he compensated through voracious engagement with books, newspapers, and pamphlets, drawing on the expanding print culture of nineteenth-century Britain. Reading was not a leisure activity but a method of intellectual survival, a means of acquiring knowledge, vocabulary, and conceptual frameworks that formal education had failed to provide consistently.

Dickens’s reading habits were notably eclectic. He consumed literature, history, political commentary, and popular journalism without strict disciplinary boundaries. This breadth allowed him to form connections across genres and social questions, fostering a holistic understanding of Victorian life rather than a narrowly specialized one. Unlike classical education, which emphasized inherited authority and canonical texts, Dickens’s self-directed reading was pragmatic and responsive to lived experience. He read to understand power, poverty, human motivation, and institutional behavior.

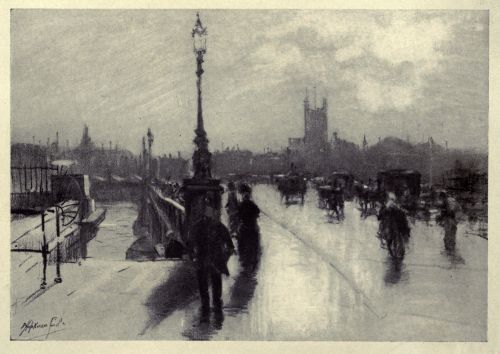

Equally important was Dickens’s education through observation. His work required him to move through diverse social spaces, from law offices to courtrooms, from crowded streets to political chambers. He cultivated an attentiveness to speech, gesture, and environment, treating everyday interactions as sources of knowledge. Observation functioned as a form of empirical inquiry. Dickens learned how social roles were performed, how authority was asserted, and how suffering was concealed beneath routines and respectability.

This observational discipline sharpened Dickens’s capacity to translate social reality into narrative form. His characters often emerge not as abstract symbols but as composites drawn from repeated encounters with recognizable types. The authenticity of his social settings owes much to this method of learning through proximity. By watching rather than theorizing, Dickens developed an understanding of Victorian society grounded in practice rather than ideology, allowing him to capture both its cruelties and its contradictions.

Self-education through reading and observation ultimately granted Dickens a distinctive intellectual authority. His knowledge was not certified by institutions but validated by accuracy, resonance, and moral urgency. This mode of learning positioned him as both participant and analyst within Victorian culture, capable of exposing injustice with credibility rooted in experience. In rejecting the limitations of formal education, Dickens did not abandon learning. He redefined it as an active, continuous process embedded in the texture of everyday life.

Shorthand, Reporting, and the Discipline of Precision

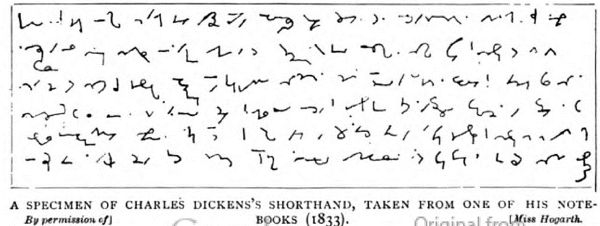

As Dickens moved into clerical and journalistic work, his self-education took on a more technical and disciplined form through the study of shorthand. Determined to advance beyond precarious employment, Dickens taught himself this demanding skill with extraordinary persistence. Shorthand was not merely a practical tool. It required acute listening, rapid comprehension, and the ability to translate spoken language into precise written form under pressure. Mastery of this system imposed a rigor that rivaled any formal curriculum.

Dickens’s entry into parliamentary reporting further intensified this discipline. Reporting debates required speed, accuracy, and an ability to capture not only words but tone, argument, and rhetorical structure. Errors carried professional consequences, and there was no space for approximation. This environment trained Dickens to process complex information swiftly and to reproduce it faithfully. The habit of exactitude cultivated through reporting would later surface in his fiction, where dialogue often carries legal, political, and moral weight without sacrificing narrative momentum.

The experience also immersed Dickens in the machinery of governance and law. By observing parliamentary proceedings firsthand, he acquired a working knowledge of political institutions that few novelists possessed. This education was neither abstract nor idealized. He witnessed procedural obstruction, rhetorical evasion, and the gap between public language and private interest. Reporting sharpened his skepticism toward institutional authority and deepened his understanding of how power operated through language, delay, and bureaucracy.

Shorthand and reporting thus functioned as a crucible for Dickens’s intellectual development. They disciplined his mind toward precision while exposing him to the structures he would later critique with such force. This phase of self-education fused technical mastery with social insight, reinforcing a lifelong commitment to clarity, accuracy, and moral accountability. The skills Dickens acquired were not ornamental. They formed the structural backbone of his narrative voice and enabled him to translate complex social realities into compelling and intelligible prose.

Experiential Knowledge and Victorian Social Critique

The authority of Dickens as a social critic rested not on abstract theory or academic training but on experiential knowledge accumulated through hardship, labor, and observation. Unlike many Victorian commentators who approached social problems from a distance, Dickens wrote from within the conditions he described. Poverty, child labor, and institutional cruelty were not intellectual puzzles to be solved but realities he had endured. This proximity granted his critique an urgency and credibility that distinguished it from contemporary moralizing discourse.

Dickens’s understanding of child labor exemplifies this experiential foundation. His own labor as a child informed portrayals of young characters trapped in exploitative systems that treated vulnerability as economic convenience. These depictions were neither sentimental nor detached. They conveyed the exhaustion, humiliation, and quiet despair that accompanied such work. By grounding narrative in lived experience, Dickens exposed child labor not as an unfortunate anomaly but as a structural feature of Victorian industrial society.

His critique of legal and bureaucratic institutions followed a similar pattern. Dickens had observed courts, prisons, and administrative offices not as symbols but as functioning systems populated by clerks, lawyers, officials, and victims. This familiarity allowed him to represent bureaucracy as a moral environment shaped by delay, indifference, and procedural cruelty. Legal systems in his work often perpetuate injustice not through overt malice but through mechanical adherence to rules divorced from human consequence. Such insight emerged from observation rather than ideology.

Experiential knowledge also shaped Dickens’s portrayal of poverty as a social condition rather than a moral failing. Having lived at the edge of destitution, he rejected narratives that attributed suffering to individual weakness. His work consistently emphasized how economic vulnerability was produced and sustained by social arrangements that punished failure while protecting privilege. This perspective challenged dominant Victorian assumptions about responsibility and deservingness, reframing poverty as a collective moral problem.

Importantly, Dickens’s critique avoided the abstraction that often accompanied reformist rhetoric. He did not reduce injustice to statistics or principles alone. Instead, he rendered social conditions legible through character, voice, and setting. This narrative strategy transformed experiential knowledge into a communicative force capable of reaching audiences across class lines. Readers were invited not merely to understand injustice but to feel its weight and recognize its mechanisms.

Through this fusion of experience and critique, Dickens redefined the role of the writer in Victorian society. He did not position himself as a detached intellectual authority but as a witness shaped by the very systems he examined. His social criticism derived its power from authenticity rather than credentials. Experiential knowledge, accumulated under conditions of necessity, enabled Dickens to articulate a sustained moral challenge to Victorian institutions, one that continues to resonate precisely because it emerged from lived reality.

Self-Education as Moral Legitimacy

For Dickens, self-education functioned not only as an intellectual pathway but as a source of moral legitimacy. In a society that increasingly equated authority with formal credentials and elite schooling, Dickens occupied an anomalous position. He spoke with confidence on matters of poverty, labor, law, and social reform without possessing the educational markers typically associated with such authority. His credibility instead derived from experience, observation, and a demonstrated commitment to representing the lives of those most affected by institutional failure.

This form of legitimacy resonated strongly with popular audiences. Dickens’s readers recognized in his work a voice shaped by familiarity rather than condescension. He wrote neither as an outsider diagnosing social problems nor as an academic theorizing from abstraction, but as someone who had inhabited multiple social positions. His self-education allowed him to move between classes, translating the experiences of the marginalized into narratives accessible to middle-class readers without diluting their moral force.

At the same time, Dickens’s position generated tension with elite intellectual culture. Critics sometimes dismissed his work as emotionally excessive or insufficiently disciplined by theory. Such critiques reveal the limits of Victorian intellectual gatekeeping, which privileged formal education as the primary marker of seriousness. Dickens’s success challenged these assumptions by demonstrating that moral insight and analytical clarity could emerge outside institutional pathways. His authority rested on accuracy, empathy, and sustained attention rather than on academic sanction.

Self-education also shaped Dickens’s ethical orientation as a writer. Having learned through hardship, he viewed knowledge as inseparable from responsibility. To understand suffering was to bear witness to it and, where possible, to expose its causes. This ethical framework distinguished Dickens from reformers who treated social problems as technical matters detached from lived experience. His narratives insisted that moral accountability could not be delegated to systems or abstractions.

In this way, Dickens transformed self-education into a form of public trust. His lack of formal schooling did not diminish his standing as a social commentator. It enhanced it. By grounding authority in experience and moral attention rather than credentials, Dickens offered an alternative model of intellectual legitimacy. His career suggests that education, when shaped by necessity and sustained engagement with human reality, can produce not only knowledge but a durable ethical claim on the public conscience.

Conclusion: Education as Survival and Vision

The life and career of Charles Dickens challenge conventional definitions of education rooted in formal schooling and credentialed expertise. Deprived of sustained institutional instruction, Dickens nonetheless acquired a depth of social understanding that surpassed many of his formally educated contemporaries. His education emerged through necessity rather than design, shaped by poverty, labor, and persistent observation. What he lacked in formal training, he replaced with attentiveness to human experience and a relentless commitment to learning from the world around him.

Dickens’s self-education functioned first as a means of survival. The skills he acquired, from shorthand to reporting, enabled him to navigate precarious economic conditions and secure professional stability. Yet survival alone does not account for the enduring significance of his education. These same experiences furnished him with insight into the structures of Victorian society, revealing how law, labor, and bureaucracy shaped human lives. Education, in this sense, became inseparable from social awareness.

Beyond survival, Dickens’s education offered a distinctive vision. His writing transformed experiential knowledge into moral critique, translating private suffering into public consciousness. By grounding social criticism in lived reality, he expanded the capacity of literature to function as a vehicle for ethical engagement. His work did not merely describe injustice. It compelled readers to recognize their participation in systems that normalized it. This achievement rested on an education forged outside classrooms but refined through discipline and reflection.

Ultimately, Dickens’s legacy suggests that education need not follow prescribed institutional paths to produce intellectual authority or moral clarity. His life affirms the possibility of learning shaped by necessity and sustained by attention, capable of generating both insight and responsibility. Education, as Dickens embodied it, was not the accumulation of credentials but the cultivation of vision. It enabled him to see society clearly and to demand that others see it as well.

Bibliography

- Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 2002.

- Altick, Richard D. The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800–1900. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957.

- Collins, Philip. Dickens and Crime. London: Macmillan, 1962.

- Cunningham, Hugh. Children and Childhood in Western Society since 1500. London: Longman, 1995.

- Dickens, Charles. David Copperfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1850.

- —-. Sketches by Boz. London: John Macrone, 1836.

- Flint, Kate. The Victorians and the Visual Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Humpherys, Anne. “Dickens and Education.” In The Cambridge Companion to Dickens, edited by John O. Jordan, 54–70. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- John, Juliet. Dickens’s Villains: Melodrama, Character, Popular Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Ledger, Sally. Dickens and the Popular Radical Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Manning, John. Dickens on Education. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1959.

- Padra, Brahmananda. “Charles Dickens and the Critique of Victorian Society: Literature as a Catalyst for Social Reform.” The Criterion: An International Journal in English 15:II (2024): 346-358.

- Patten, Robert L. “Whitewashing the Blacking Factory.” Dickens Studies Annual 46 (2015): 1-22.

- Poovey, Mary. Making a Social Body: British Cultural Formation, 1830–1864. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

- Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Tomalin, Claire. Charles Dickens: A Life. New York: Viking, 2011.

- Williams, Raymond. Culture and Society. New York: Columbia University Press, 1958.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.14.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.