In Ancien Régime France, secret arrest and detention were not anomalies or abuses at the margins of authority. They were lawfully ordained acts.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Law without Trial

Early modern France presents one of the clearest historical examples of how legality can survive even as judicial restraint disappears. Under the Ancien Régime, individuals could be arrested, detained, exiled, or subjected to home entry without formal charges, hearings, or trial. These actions were not covert violations of law. They were executed through lettres de cachet, sealed administrative orders issued in the king’s name. Their existence exposes a central paradox of legal history: the most consequential exercises of power are often those that operate entirely within a recognized legal framework.

Lettres de cachet did not function as emergency improvisations or temporary suspensions of law. They were routine instruments of governance, embedded within a legal culture that privileged order, hierarchy, and administrative discretion over adversarial procedure. Far from being exceptional, they were woven into everyday practices of discipline, family regulation, and political control. Judicial process was widely regarded as slow, public, and destabilizing, particularly in matters touching morality, loyalty, or social disorder. Administrative intervention promised speed and quiet resolution. The absence of trial was therefore not viewed as a failure of justice, but as a rational alternative to it. Legality was measured not by procedural transparency, but by conformity to sovereign authority.

This system reveals how law can be transformed without being abolished. Ancien Régime France did not lack courts, statutes, or legal professionals. What it lacked was an institutional commitment to independent review as a condition of legitimacy. The king’s authority functioned as the ultimate source of legality, allowing administrative command to replace judicial judgment without formal contradiction. Arrest without trial was lawful precisely because it originated from sovereign power rather than from adjudicated process. Over time, this internal definition of legality normalized practices that would otherwise have appeared arbitrary. The danger lay not merely in unchecked discretion, but in the way legality itself was reoriented to serve administrative ends.

The significance of lettres de cachet extends beyond their immediate historical context. They demonstrate how legality can become a vehicle for coercion when law is defined internally by those who wield power, rather than externally by independent institutions. Ancien Régime France thus offers a cautionary case: law may remain intact in form even as its capacity to restrain authority quietly erodes.

The Legal Culture of the Ancien Régime

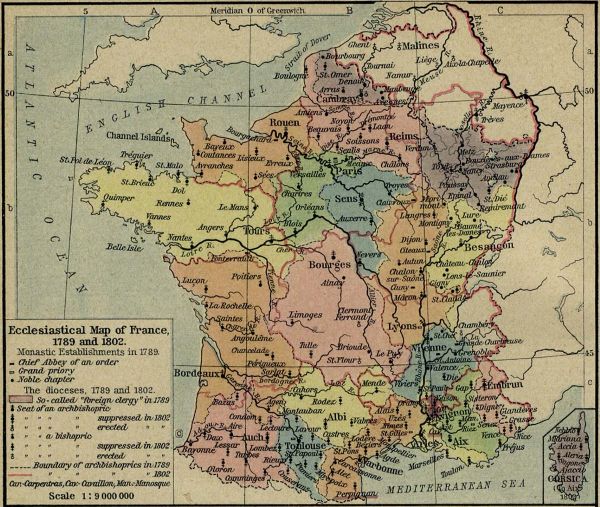

The legal culture of Ancien Régime France differed fundamentally from common law traditions that emphasized adversarial process and judicial restraint. French law operated within a fragmented and hierarchical system in which authority was distributed across royal courts, local jurisdictions, customary law, and administrative offices. Rather than serving as a unified check on power, this complexity often reinforced deference to hierarchy and status. Law was understood less as a forum for contestation than as a means of preserving social order within a stratified society. The legitimacy of legal action flowed upward toward the crown, not outward toward independent judgment, shaping expectations about obedience, discretion, and governance long before any particular instrument of repression was deployed.

Royal justice occupied a privileged position within this system. The king was regarded as the fountain of justice, and his authority permeated the legal order even when exercised indirectly. Courts such as the parlements possessed significant prestige and interpretive authority, but they did not function as independent guarantors of rights in the modern sense. Their role was to register, interpret, and occasionally resist royal measures, not to invalidate them outright. This structure limited the capacity of judicial institutions to impose sustained restraint on executive action.

Procedural protections existed, but they were unevenly applied and weakly institutionalized. Trials could be lengthy, public, and unpredictable, making them ill-suited to the state’s interest in discipline and control. Legal outcomes often depended on status, patronage, and access rather than on uniform standards. Procedural delay was increasingly framed as a threat to stability rather than a safeguard of justice. Administrative solutions promised efficiency and discretion, aligning more closely with elite expectations of governance.

The fragmentation of jurisdiction further undermined judicial coherence and weakened the possibility of consistent oversight. Overlapping courts, competing legal traditions, and jurisdictional conflicts produced uncertainty rather than protection. Litigants could be shifted between forums, delayed indefinitely, or pressured into informal resolution. Officials exploited this ambiguity to justify administrative intervention as a corrective to judicial dysfunction. When executive action bypassed courts altogether, it was often defended as a practical response to a system already perceived as cumbersome, politicized, and incapable of decisive action. Fragmentation thus did not merely fail to restrain power. It actively enabled administrative substitution for adjudication.

Administrative authority emerged not as an aberration but as a logical extension of prevailing norms. The preference for order, hierarchy, discretion, and quiet resolution created fertile ground for instruments like lettres de cachet. By allowing legality to be defined internally by the executive, the Ancien Régime legal system normalized administrative command as a legitimate substitute for judicial process. Law did not disappear, nor was it openly defied. It was redirected toward governance rather than restraint, preparing the institutional and cultural ground for secret arrest and detention to operate as lawful acts rather than constitutional crises.

What Were Lettres de Cachet?

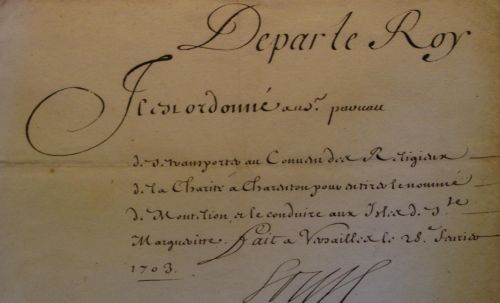

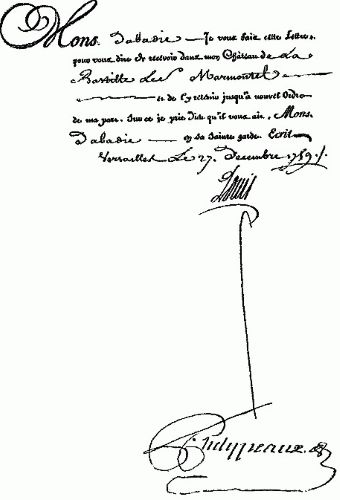

Lettres de cachet were sealed administrative orders issued in the name of the French king, authorizing actions that would otherwise have required judicial process. These orders empowered officials to arrest, detain, exile, confine individuals in prisons, hospitals, or convents, and in some cases to enter private homes, all without formal charges, hearings, or trial. Their authority rested entirely on royal prerogative and the conception of the king as the ultimate source of legality. Once issued, a lettre de cachet carried immediate legal force and was executed by administrative or military agents as a matter of routine governance. In this sense, lettres de cachet were not emergency shortcuts or aberrations. They were fully institutionalized tools embedded within the normal operation of the Ancien Régime state.

The mechanics of lettres de cachet underscore their administrative character. They were drafted by royal secretaries, sealed with the king’s private seal, and transmitted through bureaucratic channels rather than courts. Their content was typically terse, often stating only that an individual was to be detained or removed at the king’s pleasure. No evidentiary standard was required, and no explanation was owed to the subject. Silence was intentional. It protected executive discretion, avoided public justification, and insulated administrative decision-making from legal challenge.

Lettres de cachet were used across a remarkably wide range of circumstances, revealing the breadth of administrative power they enabled. They served political purposes, suppressing dissent, silencing pamphleteers, and neutralizing perceived threats to state authority. At the same time, they were deeply entangled in social and domestic governance. Families frequently petitioned the crown to confine relatives deemed disobedient, scandalous, mentally unstable, or disruptive to household order. In these cases, administrative detention was framed as corrective or protective rather than punitive. The state positioned itself as an arbiter of morality and discipline, extending administrative authority directly into private life and treating the household as an object of management rather than a protected legal sphere.

What made lettres de cachet especially significant was their legal status within the system. They did not operate outside the law or in defiance of it. They were lawful acts, issued through recognized channels of authority and immune from ordinary judicial review. No court possessed the power to invalidate them, and appeals depended on favor rather than right. This fusion of command and legality exemplified administrative law at its most absolute. Lettres de cachet demonstrate how a legal system can authorize coercion without abandoning legality itself, replacing judicial judgment with executive discretion while preserving the outward form of lawful rule.

Administrative Legality versus Judicial Legality

Lettres de cachet expose a fundamental division within the legal order of Ancien Régime France: the distinction between judicial legality and administrative legality. Judicial legality depended on procedure, public reasoning, and the possibility of contestation. It required charges, hearings, and adjudication within recognized courts. Administrative legality, by contrast, derived its authority from executive command. Its legitimacy flowed from the king’s role as sovereign rather than from any process external to that authority. Lettres de cachet operated entirely within this administrative register, bypassing judicial mechanisms without violating the legal logic of the system.

This division did not reflect a breakdown of law, but a hierarchy of legal forms. Judicial law existed, but it was subordinated to administrative command whenever order, discipline, or necessity was invoked. Courts could interpret statutes, register edicts, and adjudicate disputes, yet they lacked the power to invalidate a royal order issued under seal. Judicial legality functioned as a secondary mode of governance, activated when administration deemed it appropriate. In matters framed as sensitive or urgent, executive authority claimed the right to displace adjudication altogether.

The consequences of this hierarchy were profound and systemic. Administrative legality eliminated the need for public justification and procedural exposure. Decisions were rendered in private, reasons were withheld, and review was internal rather than adversarial. Subjects were not accused in a juridical sense; they were managed administratively. Detention, exile, or confinement became preventive rather than punitive, justified by anticipated disorder, moral concern, or political risk rather than proven wrongdoing. In this framework, legality no longer marked a boundary between lawful and unlawful action. Instead, it marked a distinction between modes of authority, with administrative command occupying the highest tier and judicial process relegated to matters deemed safe for public adjudication.

What made this system especially durable was its internal coherence and self-validation. Administrative legality did not pretend to be judicial process, nor did it deny the existence of courts or legal norms. It simply rendered them unnecessary in designated domains by reserving to the executive the power to decide when adjudication applied. By allowing authority to define the scope of its own review, the Ancien Régime legal system transformed law into an instrument of governance rather than a restraint upon it. Lettres de cachet thus reveal how legality can persist openly and confidently even as judicial restraint disappears, replaced by an internally defined administrative order that required no external confirmation to operate.

Order, Discipline, and the Logic of Necessity

The justification most consistently offered for lettres de cachet was necessity, a concept elastic enough to authorize a wide range of administrative actions while insulating them from critique. Royal officials and their defenders framed arrest, detention, and confinement not as coercive impositions, but as prudent measures required to preserve order in a complex and unstable society. Disorder was imagined not merely as actual rebellion or crime, but as a latent condition that could emerge from moral failure, political dissent, or social deviance. Judicial process, with its delays, publicity, and uncertainty, was portrayed as ill equipped to manage such risks. Necessity thus functioned as both rationale and shield, allowing administrative power to present itself as foresighted governance rather than repression.

This logic of necessity was closely tied to an expansive conception of discipline. The state did not limit its concern to overt criminality. It sought to regulate conduct that threatened social stability even if it violated no statute or ordinance. Pamphleteers, unruly nobles, insubordinate clerics, and individuals deemed morally dangerous all fell within the reach of administrative attention. Lettres de cachet enabled intervention before misconduct escalated into scandal or unrest. Administrative detention therefore operated as preventive justice, oriented toward managing perceived risk rather than adjudicating guilt.

The appeal of this system lay in its promise of benevolence and efficiency. Administrative confinement was often framed as corrective rather than punitive, particularly in cases initiated by family petitions. Parents, spouses, and guardians appealed to royal authority to discipline relatives whose conduct endangered reputation, property, or household order. The state presented itself as a neutral arbiter, stepping in where familial authority had failed. This fusion of private request and public power blurred the line between care and coercion. Discipline became a shared project between family and state, justified through necessity rather than legal violation.

Political necessity further expanded the reach of administrative power and deepened its secrecy. In an environment shaped by censorship, factional rivalry, and fear of sedition, lettres de cachet offered a means of silencing dissent without the risks inherent in prosecution. Trials exposed evidence to scrutiny, invited public sympathy, and created opportunities for resistance. Administrative detention avoided these dangers by operating quietly and conclusively. The absence of charges or explanation was reframed as a virtue rather than a defect, signaling responsible restraint rather than arbitrary power. Necessity thus justified secrecy, transforming silence into a marker of legitimate authority.

The logic of necessity proved so powerful precisely because it was cumulative and self-expanding. What counted as necessary broadened alongside the ambitions of governance. Moral discipline, family order, political loyalty, and social harmony all became grounds for intervention. Over time, necessity ceased to function as an exceptional justification and instead became the default reasoning through which administrative power operated. Lettres de cachet demonstrate how appeals to order and discipline can normalize extraordinary authority, converting discretionary power into routine practice while preserving the appearance of legality, prudence, and even benevolence.

The Household as a Site of Administrative Power

Under the Ancien Régime, the household occupied an ambiguous and politically significant position within the legal order. It was neither fully private nor entirely public, but a space where social hierarchy, moral discipline, and authority intersected. French law recognized the household as a foundational unit of governance, responsible for producing obedience, stability, and proper conduct. Disorder within the home was therefore not viewed as a purely personal matter. When domestic conflict threatened reputation, inheritance, or moral norms, it was understood to carry broader social consequences. This conception made the household a legitimate target of state concern long before overt political danger appeared.

Lettres de cachet provided the mechanism through which administrative power entered domestic space. Unlike judicial warrants, these orders did not require evidentiary justification, sworn testimony, or independent authorization. A sealed command issued in the king’s name was sufficient to authorize arrest, confinement, or removal from the household. Entry into the home under a lettre de cachet was framed not as a violation of domestic autonomy but as an act of correction. Administrative authority thus crossed the threshold of the home without contest, transforming private space into an extension of state governance.

Family petitions played a crucial role in legitimizing and normalizing this intrusion. Parents, spouses, and guardians regularly appealed to royal officials to confine relatives whose behavior was deemed disruptive, immoral, financially reckless, or socially dangerous. These petitions translated private anxiety into administrative action. By responding to such requests, the state presented itself as a partner in domestic discipline rather than an external coercive force. This collaboration blurred the line between consent and compulsion. Individuals subjected to confinement were often detained at the urging of those closest to them, yet the power exercised was unmistakably sovereign and unilateral.

This dynamic fundamentally altered the legal meaning of the home. Rather than serving as a boundary against state power, the household became a point of access for administrative authority. Domestic governance was no longer exclusively familial. It was shared with the state, which claimed the right to intervene when internal discipline was judged insufficient. The absence of judicial process meant that household members had no formal avenue for challenge or appeal. Decisions affecting liberty, confinement, and separation were rendered administratively, reinforcing the idea that legality flowed from authority rather than adjudication and that obedience preceded justification.

The treatment of the household under lettres de cachet reveals how deeply administrative legality penetrated everyday life. State power operated quietly within families, reshaping the boundary between private order and public authority while maintaining the appearance of lawful governance.

Resistance without Remedy

Opposition to lettres de cachet existed throughout the Ancien Régime, but it rarely took the form of effective legal resistance. Subjects understood that administrative arrest and detention were lawful acts within the system, even when they were experienced as unjust. This recognition shaped the nature of dissent. Complaints were framed as petitions for mercy rather than claims of right. Individuals appealed to favor, influence, or reputation, not to law as an independent standard capable of overturning administrative decisions.

Judicial institutions offered little recourse. Courts lacked jurisdiction to invalidate lettres de cachet, and magistrates generally acknowledged the supremacy of royal command in administrative matters. Even when judges privately disapproved of particular detentions, they had no formal mechanism to intervene. The law recognized the king’s authority to act outside ordinary judicial process, leaving courts structurally sidelined. This limitation was not accidental but foundational. By design, judicial legality could not check administrative legality when the latter was invoked in the name of order or necessity. Resistance therefore could not crystallize into a doctrine of rights. It remained fragmented, dependent on circumstance, and incapable of producing binding restraint.

Public criticism emerged intermittently, particularly among intellectuals and reformers who viewed lettres de cachet as symbols of despotism. Pamphlets, memoirs, and private correspondence condemned secret arrest as incompatible with justice and liberty. These critiques, however, operated largely at the level of moral argument rather than legal challenge. Because lettres de cachet were lawful within the system, critics attacked their abuse, excess, or arbitrariness rather than their validity. The language of reform emphasized moderation, transparency, or benevolence, not illegality. As a result, even sustained criticism failed to generate institutional remedies. Outrage circulated, but it could not anchor itself in enforceable legal principle.

The secrecy surrounding administrative detention further weakened resistance. Detainees were removed quietly, often without public explanation, and confined in locations that limited communication. Families might know the cause, but broader communities often did not. This isolation prevented collective mobilization and muted public response. Without trials, charges, or formal proceedings, there were no visible events around which opposition could coalesce. Administrative legality thus functioned not only as authority, but as a mechanism of silence, dissolving resistance before it could take public or juridical form.

The result was a system in which power faced discontent without accountability. Individuals might suffer, protest privately, or seek intervention through patronage, but they could not compel review as a matter of right. Resistance existed, but it lacked remedy. Lettres de cachet demonstrate how legality can absorb dissent by denying it institutional expression, allowing coercive practices to persist not through terror alone, but through the quiet normalization of administrative authority.

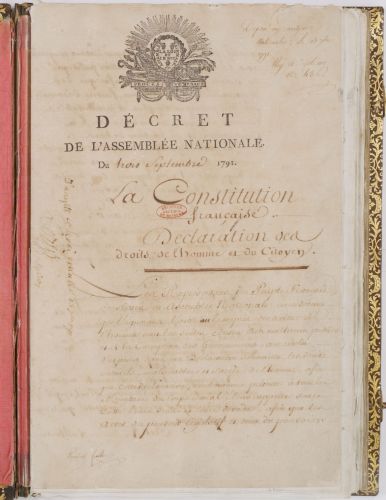

Revolutionary Rejection and the Myth of Sudden Break

The French Revolution is often portrayed as a clean rupture with the administrative practices of the Ancien Régime, and lettres de cachet became one of its most powerful symbols of despotism. Revolutionary rhetoric cast secret arrest as the clearest embodiment of arbitrary rule, incompatible with liberty, citizenship, and the sovereignty of law. Pamphlets, speeches, and early legislative acts condemned the practice as an affront to justice itself. When revolutionary authorities formally abolished lettres de cachet, the act was framed as a moral and constitutional cleansing, proof that legality had been restored to public life. In revolutionary memory, the destruction of secret administrative detention marked the moment when law was reclaimed from power and returned to the people.

This rejection, however, was more rhetorical than structural. While lettres de cachet as instruments were abolished, the underlying logic that had sustained them proved remarkably resilient. The Revolution dismantled royal prerogative, but it did not immediately replace administrative legality with consistent judicial restraint. Authority was redistributed rather than eliminated, shifting from the crown to assemblies, committees, and revolutionary officials. The new regime inherited a state accustomed to governing through necessity, discretion, and preventive intervention. The vocabulary of legitimacy changed, but the assumption that order sometimes required action beyond ordinary legal process remained intact.

Emergency power emerged almost immediately as a governing principle. Revolutionary leaders justified exceptional measures as temporary responses to existential threats, whether internal counterrevolution or foreign invasion. Detention without trial, surveillance, and administrative policing reappeared under new legal forms, now authorized by revolutionary committees or legislative bodies rather than by royal command. These measures were framed as expressions of popular sovereignty rather than monarchical authority, yet they reproduced the same displacement of judicial process in favor of administrative decision-making. Necessity once again became the master justification, overriding procedural restraint in the name of survival.

The Revolutionary Tribunal and the broader machinery of revolutionary justice further complicate the narrative of rupture. Although these institutions employed formal procedures, they were designed to accelerate judgment, limit defense, and prioritize political necessity over individual rights. Trials were public, but they were compressed and directional, aimed less at adjudicating guilt than at affirming revolutionary legitimacy. Judicial form survived, but judicial independence did not. Law functioned as an instrument of purification and security rather than as a barrier against coercive power. Transparency did not prevent severity; it merely altered its presentation.

This continuity reveals the danger of treating the Revolution as a definitive break with administrative coercion. The abolition of lettres de cachet removed a symbol, not a governing structure. Administrative legality persisted because it addressed problems revolutionary leaders believed judicial process could not resolve quickly or decisively. Fear of conspiracy, instability, and collapse reinforced the belief that legality must remain flexible in moments of danger. Once again, necessity justified discretion, and power retained the authority to decide when law could be suspended or accelerated. The shift was ideological rather than institutional, substituting revolutionary virtue for royal command while preserving administrative dominance.

The myth of sudden break therefore obscures a deeper continuity in the relationship between law and power. The Revolution transformed the source of authority, but it preserved the temptation to bypass independent review in the name of collective survival. Lettres de cachet disappeared as a practice, but the administrative logic they embodied endured, reemerging in new legal guises. This persistence reinforces the central argument of this essay: legality can survive radical political change while continuing to authorize coercion, so long as power retains the ability to define necessity and legality from within.

Lettres de Cachet and Modern Administrative Enforcement

The relevance of lettres de cachet does not lie in their specific historical form, but in the administrative logic they exemplify. Early modern France demonstrates how executive authority can define legality internally, bypassing judicial review while remaining formally lawful. Modern administrative enforcement operates within very different institutional frameworks, yet the structural pattern is strikingly familiar. When agencies claim authority to arrest, detain, or enter private space based on internal authorization rather than judicial warrants, they echo the same substitution of administrative legality for judicial legality that characterized the Ancien Régime.

In contemporary systems, executive agencies often justify extraordinary enforcement powers through internal memoranda, policy directives, or emergency interpretations of statutory authority. These instruments resemble lettres de cachet not in symbolism but in function. They authorize coercive action without prior independent review, relying on executive determination rather than adversarial process. The justification is again necessity: efficiency, security, or operational urgency. As in early modern France, legality is preserved in form while judicial restraint is displaced by administrative discretion.

This comparison does not depend on claims of equivalence between monarchies and modern constitutional states. The danger lies not in despotism returning wholesale, but in familiar structural patterns reasserting themselves within new legal vocabularies. Administrative enforcement today often insists that its actions are lawful precisely because they conform to internally generated rules, agency interpretations, or executive guidance. Judicial review, when it occurs, is frequently retrospective, assessing conduct after liberty has already been curtailed or homes entered. Such review may correct excesses, but it cannot replicate the restraining function of prior authorization. The crucial issue is not whether courts exist, but whether they are positioned to decide legality before coercive power is exercised.

Lettres de cachet serve as a warning precisely because they were legal, normalized, and bureaucratically routine. They show how coercive authority can operate smoothly, predictably, and lawfully without judicial oversight, embedding extraordinary power into ordinary administration. Modern administrative enforcement confronts the same temptation to internalize legality in the name of order, efficiency, or necessity. History suggests that the central question is not whether power follows rules, but who defines those rules and who reviews them in advance. When administrative authorization replaces judicial judgment, legality may endure, but restraint steadily erodes, often without dramatic rupture or overt illegality.

Conclusion: When Legality Becomes the Problem

The history of lettres de cachet demonstrates that the gravest threats to liberty do not always arise from lawlessness or overt tyranny. They emerge instead from systems in which power operates comfortably within legal form while escaping legal restraint. In Ancien Régime France, secret arrest and detention were not anomalies or abuses at the margins of authority. They were lawful acts, executed through recognized administrative channels and justified by accepted doctrines of necessity and order. The danger was not that law vanished, but that it was repurposed to serve governance rather than to restrain it.

This case reveals a recurring pattern in the relationship between law and power. When legality is defined internally by executive authority, judicial review becomes optional rather than foundational. Process is treated as an inconvenience, transparency as a risk, and restraint as a liability. Administrative legality promises efficiency, discretion, and stability, yet it does so by relocating judgment from independent institutions to the very actors exercising coercive power. The result is a legal order that functions smoothly while hollowing out the principles that give legality its moral and political meaning.

The endurance of this pattern across regimes underscores its historical and contemporary significance. The abolition of lettres de cachet did not eliminate administrative coercion. It altered its symbols and sources of authorization while leaving intact the deeper logic that permitted power to bypass independent review. Revolutionary France condemned secret arrest while simultaneously institutionalizing emergency measures that privileged necessity over adjudication. Later constitutional systems repeated this pattern under different legal vocabularies, preserving courts and rights in theory while expanding administrative discretion in practice. The persistence of detention, surveillance, and warrantless entry under successive regimes suggests that the problem is not tied to monarchy, revolution, or ideology, but to the structural appeal of administrative legality itself.

The lesson of lettres de cachet is therefore neither antiquarian nor merely cautionary. It is diagnostic. Law does not protect liberty simply by existing, nor by multiplying statutes or procedures. It protects liberty only when legality is anchored to independent judgment exercised before power acts. When that anchor is loosened, legality becomes self-referential, power expands without spectacle, and restraint recedes without formal repeal. In such moments, the danger is not the collapse of law, but its transformation into an instrument that authorizes coercion while retaining the appearance of legitimacy. The most enduring threat, as Ancien Régime France reveals, is a legal order that remains intact precisely because it no longer restrains.

Bibliography

- Ackerman, Bruce. The Decline and Fall of the American Republic. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Beik, William. Absolutism and Society in Seventeenth-Century France. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- Darnton, Robert. The Literary Underground of the Old Regime. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982.

- Davis, Natalie Zemon. “Ghosts, Kin, and Progeny: Some Features of Family Life in Early Modern France.” Daedalus 106:2 (1977): 87-114.

- Dincecco, Mark. “Fragmented Authority from Ancien Régime to Modernity: A Quantitative Analysis.” Journal of Institutional Economics 6:3 (2010): 305-328.

- Doyle, William. Origins of the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

- —-. Venality: The Sale of Offices in Eighteenth-Century France. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Farge, Arlette, and Michel Foucault. Disorderly Families: Infamous Letters from the Bastille Archives. Translated by Thomas Scott-Railton. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books, 1975.

- Furet, François. Interpreting the French Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

- Hunt, Lynn. Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

- Krynen, Jacques. L’Empire du roi: Idées et croyances politiques en France, XIIIe–XVe siècle. Paris: Gallimard, 1993.

- Kumar, Sanjeev. “Impact of Intellectuals and Philosophers in French Revolution 1789.” International Journal of History 2:1 (2020): 56-59.

- Merrick, Jeffrey. The Desacralization of the French Monarchy in the Eighteenth Century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990.

- Mousnier, Roland. The Institutions of France under the Absolute Monarchy, 1598–1789. Translated by Brian Pearce. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.

- Tackett, Timothy. When the King Took Flight. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society. Translated by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1921.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.28.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.