When education abandons historical inquiry in favor of moral reassurance, it ceases to teach history at all. What remains is not knowledge but affirmation.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Teaching the Nation to Believe

Education is often presented as a neutral transmission of knowledge, a space where facts are conveyed and skills developed. Yet in nationalist regimes, schooling functions less as a site of inquiry than as an instrument of moral formation. Classrooms become arenas where loyalty is cultivated, identity is fixed, and the nation is rendered morally coherent. What is taught is not simply history, but a way of feeling about history, one that aligns belief with belonging and discourages doubt as disloyalty.

In the twentieth century, authoritarian and nationalist states invested heavily in this transformation of education. Francoist Spain and the Soviet Union, despite their ideological differences, shared a commitment to historical mythmaking as a pedagogical strategy. Textbooks were rewritten to impose clarity where the past was fractured. Museums and monuments reinforced simplified narratives of righteousness and destiny. Dissenters, internal violence, and moral ambiguity were removed or recast as threats to national survival. History was reorganized into a moral fable in which the nation was always justified and opposition was either criminal or invisible.

This process did not arise from ignorance or scholarly failure. It was deliberate. Children were not taught to think historically, to weigh evidence, or to confront contradiction. They were taught to believe. Education prioritized certainty over inquiry, reverence over analysis, and emotional identification over critical distance. By shaping historical consciousness early, regimes ensured that loyalty preceded understanding and that myth was absorbed before skepticism could form.

The significance of this pattern extends beyond the regimes that perfected it. When political leaders demand “patriotic” education and accuse institutions of betrayal for teaching complexity, violence, or dissent, they are drawing from a well-established authoritarian script. The cultivation of innocence through selective history is not a defensive act. It is a mechanism of control. Understanding how nationalist regimes taught belief rather than history clarifies why historical complexity remains threatening to power and why education continues to be a central battleground in struggles over memory, identity, and authority.

Myth, Memory, and the Authoritarian Imagination

Authoritarian regimes require a particular relationship to the past, one structured around certainty rather than inquiry. They cannot tolerate history as an open field of interpretation because ambiguity threatens legitimacy and pluralism weakens authority. Myth provides what history, honestly pursued, cannot guarantee: moral clarity, narrative closure, and emotional certainty. In the authoritarian imagination, the past must affirm the present and anticipate no alternative futures. Events are arranged not to explain complexity or contingency but to confirm righteousness and inevitability. Memory becomes selective, purposeful, and disciplined, shaped to stabilize power rather than to illuminate truth.

Myth differs from history not because it is false, but because it is resolved. Where history raises questions, myth supplies answers. Where history exposes contradiction, myth insists on coherence. Authoritarian narratives depend on this distinction. They present the nation as an enduring moral subject whose actions are always justified by necessity, destiny, or virtue. Conflict appears only as trial. Violence appears only as defense. Failure is either erased or reframed as betrayal by internal enemies.

This mythic structure simplifies moral responsibility. By dividing the past into heroes and traitors, regimes eliminate the need for ethical ambiguity. The nation becomes incapable of wrongdoing by definition. Those who suffer under state violence are either absent from the narrative or reclassified as obstacles to progress. In this framework, dissent does not represent alternative interpretation. It represents moral corruption. Historical disagreement becomes political threat.

Memory under authoritarianism is therefore not a repository but a weapon. Institutions of remembrance do not preserve the past; they enforce it. Official commemorations privilege triumph over trauma and unity over fracture, substituting celebration for reckoning. Silences are as important as declarations, and omissions are as deliberate as monuments. What is not remembered cannot trouble the present, and what is remembered is carefully shaped to produce loyalty rather than reflection. Memory is curated to feel complete, leaving no space for doubt or empathy beyond the sanctioned frame.

The authoritarian imagination depends on this managed memory because it stabilizes power without constant coercion. When myth is internalized, control becomes self sustaining, operating through belief rather than force. Citizens learn not only what to remember but how to remember, adopting the emotional posture prescribed by the state. History ceases to be a means of understanding change and becomes a ritual affirmation of permanence. In this transformation, memory no longer belongs to the past. It belongs to authority.

Francoist Spain: Catholic Nationalism and Historical Purification

The Franco regime emerged from civil war with a foundational problem of legitimacy. Its victory was not the product of national consensus but of violent suppression, foreign assistance, and prolonged repression. To stabilize authority, Francoism required a purified version of Spanish history that transformed civil conflict into moral necessity. The past was reorganized to present the regime not as one faction among many but as the embodiment of Spain itself, restoring order after a period of chaos and degeneration.

Central to this project was the fusion of nationalism with Catholicism. Francoist ideology framed Spain as an inherently Catholic nation whose true identity had been threatened by secularism, regionalism, and leftist politics. The Civil War was recast as a crusade rather than a political struggle, a righteous defense of faith and tradition against atheism and foreign corruption. This framing collapsed political disagreement into moral transgression. Republican forces were not merely opponents but enemies of God, order, and civilization itself. By sacralizing the conflict, the regime transformed violence into virtue and repression into moral duty. Executions, imprisonment, and exile could be understood not as acts of state terror but as necessary acts of purification in service of national redemption.

Historical revision followed institutional lines with remarkable thoroughness. Textbooks were rewritten to excise Republican achievements and to portray the Second Republic as a period of disorder, immorality, and national humiliation, incapable of governing a coherent Spain. Progressive reforms were reframed as symptoms of decay rather than democratic development. Regional histories, particularly those of Catalonia and the Basque Country, were suppressed or folded into a homogenized narrative of Spanish unity, denying the legitimacy of linguistic, cultural, and political diversity. Pluralism disappeared from the historical record, replaced by a monolithic story in which deviation itself became evidence of treason. What remained was a narrative of continuity, authority, and moral rectitude centered on the nation as an eternal Catholic entity momentarily disrupted and then heroically restored.

This process was not an improvisation born of ignorance. It was a coordinated effort involving educators, clergy, and state institutions. History became a tool of absolution, cleansing the regime of responsibility by relocating guilt onto abstract forces such as decadence or foreign influence. By purifying the past, Francoism trained citizens to view repression as protection and dissent as betrayal. The nation learned to remember itself without contradiction, a discipline of memory that sustained authoritarian legitimacy and would shape Spanish historical consciousness long after the dictatorship’s formal end.

Classrooms of Loyalty: Education under Franco

Education under Franco was designed to produce obedience rather than understanding. Schools were not spaces for inquiry but mechanisms for moral and political conditioning, tightly aligned with the regime’s vision of order and authority. The state viewed education as a frontline institution in the consolidation of authoritarian rule, one capable of shaping citizens long before dissent could form. Classrooms were expected to instill discipline, reverence, and acceptance of hierarchy as natural features of social life. Historical thinking, with its emphasis on evidence, causation, and contingency, posed a threat to this objective and was therefore systematically displaced by rote learning, moral instruction, and ideological certainty.

Curriculum control was centralized and rigid. Textbooks were vetted to ensure ideological conformity, and teachers were monitored for signs of dissent or deviation. History lessons emphasized continuity, authority, and religious destiny, presenting Spain as an eternal nation temporarily disrupted by liberalism and restored through sacrifice. The Civil War was simplified into a morality tale of order triumphing over chaos, leaving no space for competing interpretations. Students were taught certainty rather than evaluation, reverence rather than skepticism.

Regional identities and histories were actively suppressed within the classroom. Languages such as Catalan and Basque were excluded from instruction, and local historical narratives were either erased or reframed as subordinate to a unified Spanish story. This homogenization was not merely cultural but political. By denying the legitimacy of plural identities, the regime reinforced the idea that loyalty to the nation required the abandonment of difference. Education thus became an instrument of cultural discipline, aligning personal identity with state authority.

The cumulative effect of this system was a population trained to associate learning with obedience. Intellectual curiosity was discouraged, and questioning official narratives carried social and professional risk for both students and educators. Students learned to perform loyalty through memorization and repetition, internalizing the idea that history existed to affirm the present order rather than to explain change or conflict. Belief became habitual, reinforced through daily ritual rather than argument. In this way, Francoist education did not simply transmit ideology. It trained emotional reflexes, ensuring that the myths of the regime were absorbed as common sense and would endure long after the classroom lessons themselves had faded.

The Soviet Union: Revolutionary Myth and Historical Teleology

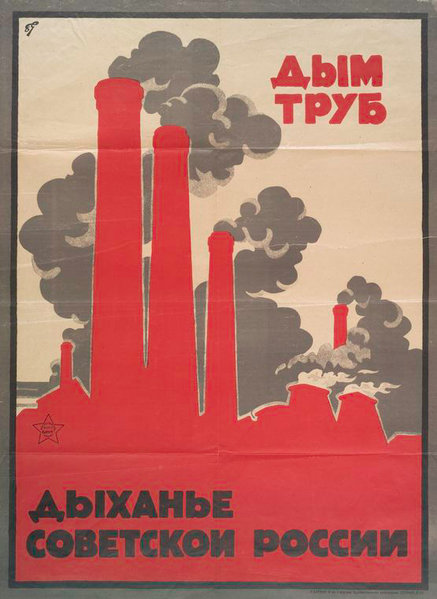

Soviet power rested on a distinctive historical claim: that history itself had a direction and that the state embodied its fulfillment. Unlike Francoist Spain, which looked backward to tradition and faith, the Soviet Union looked forward, grounding legitimacy in revolutionary inevitability. Marxist theory was transformed into historical destiny, presenting socialism not as one political possibility among many but as the necessary outcome of human development. This teleological framework allowed the regime to present itself as history’s agent rather than its subject.

Within this narrative, the Bolshevik Revolution became a foundational myth rather than a contested event. Complexity was stripped away in favor of moral clarity and narrative discipline. The Party appeared as the conscious force guiding humanity toward emancipation, uniquely capable of interpreting and directing historical movement. Opponents were cast not merely as political rivals but as enemies of progress itself, standing in the way of an inevitable future. Civil war, famine, and coercion were reframed as unavoidable stages in the transition from exploitation to equality, tragic but necessary costs of historical transformation. Violence was not denied, but it was justified in advance by the promise of redemption, rendering moral evaluation secondary to historical necessity and insulating the regime from accountability.

Historical teleology also functioned to erase contingency. Events that contradicted the official narrative, including policy failures, internal repression, and popular resistance, were either omitted or reframed as temporary deviations. Stalinist purges, forced collectivization, and mass imprisonment disappeared from educational history or were explained as defensive measures against sabotage. By presenting history as a linear ascent toward socialism, the regime eliminated the possibility that alternative paths might have existed or that the Party itself could be responsible for suffering.

The authority of this narrative depended on its claim to scientific legitimacy. Marxism-Leninism was taught not as interpretation but as law, a set of principles governing historical development with the certainty of natural science. Textbooks emphasized inevitability, causation, and outcome over debate or evidence, training students to recognize conclusions rather than to test arguments. Questioning the narrative was therefore not disagreement but error, ignorance, or ideological corruption. Historical inquiry gave way to doctrinal instruction, and the past was valuable only insofar as it illustrated predetermined truths already known in advance.

Through this fusion of myth and inevitability, Soviet historical consciousness trained citizens to see the present as justified by the future. Sacrifice became meaningful only in retrospect, and suffering was rendered invisible by its promised redemption. Individuals were encouraged to endure hardship not because it was just, but because it was temporary within a grand historical arc. The result was a powerful moral economy in which loyalty to the state was equated with loyalty to history itself. In this framework, dissent was not merely political opposition or intellectual disagreement. It was resistance to the direction of time, an act portrayed as futile, regressive, and morally suspect.

Soviet Schools and the Manufacture of Belief

Soviet education functioned as a system for producing belief rather than cultivating historical judgment. Schools were designed to internalize ideological certainty from an early age, ensuring that loyalty to the state preceded independent reasoning. History classrooms did not invite students to evaluate evidence or debate interpretation. They trained students to recognize correct conclusions and to reproduce them with confidence. The purpose of learning was not understanding but alignment.

Textbooks served as ideological scripts rather than analytical tools. Historical narratives followed a fixed structure in which class struggle advanced predictably toward socialist triumph, leaving no room for contingency or alternative outcomes. The Communist Party occupied the role of moral protagonist, presented as uniquely capable of interpreting and guiding historical forces. Enemies of the state appeared as reactionary obstacles to progress rather than as political actors with competing visions. Complexity was flattened into certainty, and contradiction was treated as error. By encountering the past only through predetermined conclusions, students learned to associate historical knowledge with doctrinal correctness rather than inquiry.

Pedagogy reinforced emotional identification over critical distance. Students were encouraged to admire revolutionary figures, mourn approved sacrifices, and internalize the language of struggle, vigilance, and victory. Classroom rituals, commemorations, youth organizations, and public performances extended these lessons beyond textbooks, transforming history into lived experience rather than intellectual engagement. Participation itself became proof of belief. Through repetition, ceremony, and collective affirmation, ideology was woven into daily routine, making loyalty feel natural and doubt feel disruptive. History was not something to be examined from a distance. It was something to be inhabited.

The result was a population trained to mistake narrative coherence for truth. Because the system rewarded affirmation rather than analysis, doubt became both intellectually suspect and morally dangerous. Students learned not only what to believe but how belief should feel: confident, resolved, and unquestioning. In this way, Soviet schools did not merely transmit ideology. They normalized it, ensuring that myth functioned as common sense and that historical thinking itself appeared unnecessary, even subversive.

Museums, Monuments, and National Memory

Classroom instruction did not operate in isolation. Authoritarian regimes extended educational mythmaking into public space through museums, monuments, and commemorative landscapes that reinforced the same moral narratives taught in schools. These institutions functioned as permanent classrooms, shaping historical understanding through architecture, display, and ritual. By presenting national history as visually settled and emotionally coherent, they reduced the need for explicit instruction. The lesson appeared self evident, embedded in stone, bronze, and curated glass cases.

In both Francoist Spain and the Soviet Union, museums were structured to narrate inevitability and righteousness. Exhibits emphasized origins, struggle, and triumph while minimizing internal conflict or moral fracture. Revolutionary sacrifice, national unity, and heroic leadership were foregrounded as timeless virtues. Violence committed by the state was either omitted or reframed as defensive necessity. The museum visitor was not invited to question how power was exercised but to admire the outcome it produced. Display replaced argument, offering reverence in place of explanation.

Monuments performed a similar function through selective commemoration, but with even greater permanence. Statues and memorials celebrated soldiers, martyrs, and leaders aligned with the regime’s moral vision, while victims of repression, political prisoners, and internal dissenters were excluded from public memory. Absence itself became instructive. What was not commemorated appeared unworthy of remembrance, or worse, illegitimate. Through repetition and durability, monuments trained citizens to associate national virtue with obedience and sacrifice, while rendering alternative experiences historically unintelligible. Stone and bronze fixed the moral hierarchy of the past, making it resistant to challenge even when lived memory contradicted official narratives.

These spaces also disciplined emotion in deliberate ways. Public ceremonies, anniversaries, and guided visits cultivated reverence, gratitude, and identification rather than critical distance. History was experienced collectively, reinforcing shared affect rather than individual interpretation. The combination of spectacle, ritual, and spatial authority made dissent feel inappropriate, even profane, a violation not just of politics but of memory itself. Museums and monuments thus functioned not only as historical narrators but as emotional regulators, shaping how the past should be felt as much as how it should be known, and narrowing the range of acceptable response to admiration or silence.

By extending myth from the classroom into everyday civic life, authoritarian regimes ensured that historical belief did not depend on constant enforcement. Citizens encountered the same narratives across institutions, environments, and life stages. National memory became ambient, absorbed rather than debated. In this way, museums and monuments completed the educational project, transforming history into an unquestioned inheritance and rendering alternative memories marginal, invisible, or illegitimate.

Children as the Target Audience

Authoritarian mythmaking focused most intensely on children because childhood offered the greatest opportunity for permanence. Regimes understood that beliefs formed early were more resilient than those adopted later under coercion or fear. By shaping historical consciousness before skepticism developed, nationalist systems could naturalize ideology rather than impose it overtly. Memory formed in childhood felt intuitive rather than taught, inherited rather than instructed. Children were not merely students of the nation’s story. They were its future custodians, entrusted with carrying myth forward as unquestioned truth long after the mechanisms of repression had faded from view.

Instruction aimed at youth relied on simplification as strategy rather than pedagogical necessity. Complex historical causation was reduced to moral binaries that children could easily absorb and reproduce, not because complexity was beyond their grasp but because it undermined certainty. Heroes embodied virtue. Enemies embodied corruption. Ambiguity was eliminated because it introduced choice, and choice threatened loyalty. By teaching history as a story of moral inevitability rather than contested experience, regimes ensured that allegiance preceded understanding and that questioning appeared abnormal rather than intellectually responsible. Historical thinking was displaced by moral rehearsal, training students to recognize approved conclusions rather than to evaluate evidence.

Youth organizations, ceremonies, and extracurricular rituals reinforced these lessons beyond the classroom. Participation cultivated emotional attachment to national narratives through songs, uniforms, pledges, and commemorations. History became experiential rather than analytical, embedded in identity formation and social belonging. To accept the narrative was to belong. To question it was to risk exclusion. In this way, belief was woven into daily life, making ideological conformity feel like common sense rather than compliance.

The long-term consequence of targeting children was the production of adults who experienced myth as memory rather than doctrine. Because these narratives were learned before the development of critical distance, they were recalled with emotional authority and defended as heritage. Challenges to historical myth thus appeared not as scholarly disagreements but as personal affronts. By securing belief in childhood, authoritarian regimes ensured that myth would outlive repression, continuing to shape political culture even after institutions of overt control weakened.

Manufactured Innocence and the Fear of Complexity

Authoritarian education depends on a carefully cultivated innocence, one that is not the absence of knowledge but the presence of reassurance. Complexity threatens this condition because it introduces contingency, responsibility, and the possibility of moral failure. By contrast, simplified narratives offer clarity and emotional safety. The nation appears coherent, purposeful, and justified. Violence, contradiction, and internal conflict are smoothed away, allowing citizens to inhabit a past that affirms identity rather than challenges it.

This manufactured innocence is not naïveté. It is a political achievement produced through sustained institutional effort. Regimes work deliberately to remove historical friction, teaching citizens to experience discomfort as error rather than insight and doubt as weakness rather than rigor. Ambiguity becomes suspicious, something to be corrected rather than explored. Competing interpretations are framed as threats to unity, cohesion, and moral order. When complexity is introduced, it is treated not as intellectual enrichment but as destabilization, a corrosive force that undermines confidence in the nation and its institutions. In this environment, historical doubt is easily recast as disloyalty, and curiosity itself becomes suspect.

The fear of complexity also explains why pluralism is so often targeted. Multiple perspectives expose the constructed nature of national narratives and reveal that authority depends on selection, emphasis, and omission. Authoritarian systems therefore equate complexity with relativism and relativism with moral collapse, insisting that only a single, unified story can sustain social order. Teaching students that the past is contested risks teaching them that power is contingent and revisable. Manufactured innocence protects authority by making that lesson unthinkable, replacing inquiry with certainty and interpretation with obedience.

The result is a historical consciousness trained to seek comfort rather than truth. Citizens raised within such systems are not incapable of understanding complexity; they have been conditioned to resist it. When confronted with evidence of repression, exclusion, or violence, they experience not curiosity but threat. Innocence becomes armor, shielding identity from reckoning. In this way, the fear of complexity is not a side effect of authoritarian education. It is its central safeguard.

The American Echo: ‘Patriotic Education’ and Authoritarian Continuity

Calls for “patriotic education” in the United States do not emerge in a historical vacuum. They draw upon a familiar logic in which national identity is treated as fragile and history as a potential threat rather than a resource for understanding. When political leaders insist that schools must promote pride rather than complexity, they echo a long authoritarian tradition that equates loyalty with belief and inquiry with subversion. The language is softer and the institutions more pluralistic, but the underlying impulse is recognizably old: history must reassure, not unsettle. What is framed as protection of national unity is, in practice, an effort to manage memory and contain moral discomfort before it can provoke reflection or critique.

In this framework, discomfort becomes the central danger. Teaching about slavery, racial violence, imperial expansion, or state repression is framed as an attack on the nation rather than an effort to understand it. Complexity is rebranded as cynicism. Structural analysis is dismissed as ideological indoctrination. By redefining critical history as antipatriotic, contemporary movements seek to reassert narrative control, narrowing the range of acceptable interpretation without openly abolishing academic freedom.

Educational policy has become the primary terrain for this struggle, revealing how deeply memory and power remain intertwined. Legislative efforts to restrict how race, inequality, or historical injustice may be discussed in classrooms rely on the same logic that animated authoritarian curricula elsewhere: students must be shielded from moral ambiguity. Teachers are instructed to emphasize unity, balance, and neutrality while avoiding material that might provoke anger, shame, or doubt. Yet this demand for neutrality is itself ideological. It presumes that the past can be taught without confronting harm and that silence constitutes fairness. The result is not balance but omission, a curriculum shaped by fear of what historical understanding might require ethically or politically.

Museums, libraries, and cultural institutions have likewise become targets, extending the struggle beyond the classroom. Exhibits that foreground enslavement, Indigenous dispossession, or state violence are accused of divisiveness, pessimism, or historical distortion. Funding threats, donor pressure, and public campaigns encourage institutions to retreat into safer narratives of progress and achievement. As in earlier nationalist regimes, the goal is not to eliminate history but to discipline it, ensuring that public memory affirms inherited innocence rather than invites reckoning. The message is consistent: history may be displayed, but only in forms that do not disturb collective self regard.

What makes the American case distinctive is not the logic but the denial of continuity. Because the United States defines itself through democratic ideals, efforts to constrain historical inquiry are often framed as defenses of freedom rather than limits upon it. Yet the insistence that history must inspire pride rather than understanding reproduces the same moral economy seen in authoritarian systems. Innocence is treated as a civic virtue, and critique as a civic threat.

The danger of this approach lies not only in what it erases but in what it teaches citizens to expect from history. When education is tasked with emotional reassurance, students learn to resist evidence that complicates identity. They are trained, subtly but effectively, to mistake myth for heritage and comfort for truth. In this sense, “patriotic education” is not a neutral preference. It is a recognizable strategy of power, one that seeks continuity with authoritarian traditions by ensuring that belief once again precedes understanding.

Conclusion: When Education Stops Teaching History

When education abandons historical inquiry in favor of moral reassurance, it ceases to teach history at all. What remains is not knowledge but affirmation, a curated narrative designed to protect identity rather than illuminate the past. Across nationalist regimes, the pattern is consistent and unmistakable: complexity is treated as danger, ambiguity as disloyalty, and critique as threat. History is reduced to a moral fable in which the nation is always justified and power is always necessary. In such systems, education no longer functions as a means of understanding change, causation, or human agency. It becomes a mechanism for stabilizing authority by training citizens to accept inherited narratives without interrogation.

The cases of Francoist Spain and the Soviet Union demonstrate that this transformation is neither accidental nor benign. It requires sustained institutional effort, from textbook revision and curriculum control to museums, monuments, and youth organizations that reinforce belief beyond the classroom. Children are taught not how to think historically but how to feel historically, absorbing certainty before skepticism can form. Loyalty is cultivated as a reflex, not a conclusion. The result is manufactured innocence, a condition in which citizens experience myth as memory and reassurance as heritage. Violence, dissent, and contradiction do not disappear from history. They are rendered unspeakable, stripped of interpretive weight, and displaced beyond the boundaries of legitimate inquiry.

The persistence of these patterns in contemporary debates over education underscores their relevance. When history is demanded to inspire pride rather than understanding, when institutions are attacked for teaching discomfort, and when complexity is framed as ideological corruption, the logic of authoritarian pedagogy reasserts itself. The language may differ and the political context may be democratic, but the underlying strategy remains the same: belief must precede understanding, and innocence must be preserved at the expense of truth. Education becomes a site of control rather than a space for reckoning.

To insist on historical thinking in such conditions is not to undermine civic life but to defend it. History that confronts violence, contradiction, and contingency does not weaken societies. It prepares them to live honestly with their past. When education stops teaching history, it trains citizens to fear complexity and to mistake comfort for truth. Reclaiming history as inquiry rather than inheritance is therefore not merely an academic task. It is a democratic necessity.

Bibliography

- Appleby, Joyce, Lynn Hunt, and Margaret Jacob. Telling the Truth about History. New York: W. W. Norton, 1994.

- Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1951.

- Assmann, Jan. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Bennett, Tony. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London: Routledge, 1995.

- Boyd, Carolyn P. Historia Patria: Politics, History, and National Identity in Spain, 1875–1975. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997.

- Burston, Daniel. “’It Can’t Happen Here’: Trump, Authoritarianism and American Politics.” Psychotherapy & Politics International 15:1 (2017): 1-9.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. Education and Social Mobility in the Soviet Union 1921–1934. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- —-. Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Forest, Benjamin, and Juliet Johnson. “Monumental Politics: Regime Type and Public Memory in Post-Communist States.” Post-Soviet Affairs 18:3 (2002): 243–267.

- Graham, Helen. The Spanish Civil War: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Haider, Asad. “Authoritarianism and Ideology.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 23:1,2 (2021).

- Hobsbawm, Eric. Nations and Nationalism since 1780. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger, eds. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Jackson, Gabriel. “The Franco Era in Historical Perspective.” The Centennial Review 20:2 (1976): 103-127.

- Kotkin, Stephen. Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

- Laudo, Xavier and Conrad Vilanou. “Educational Discourse in Spain during the Early Franco Regime (1936-1943): Toward a Genealogy of Doctrine and Concepts.” Paedagogica Historica 51:4 (2015): 434-454.

- Moradiellos, Enrique. Franco: Anatomy of a Dictator. London: I.B. Tauris, 2018.

- Moreno, Ismael Saz. España contra España: Los nacionalismos franquistas. Madrid: Marcial Pons, 2003.

- Richards, Michael. A Time of Silence: Civil War and the Culture of Repression in Franco’s Spain, 1936–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Service, Robert. A History of Modern Russia: From Nicholas II to Vladimir Putin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor. The Soviet Experiment: Russia, the USSR, and the Successor States. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.

- Tumarkin, Nina. The Living and the Dead: The Rise and Fall of the Cult of World War II in Russia. New York: Basic Books, 1994.

- Van Alphen, Ernst. Caught by History: Holocaust Effects in Contemporary Art, Literature, and Theory. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997.

- White, Hayden. Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

- Young, James E. The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

- Yurchak, Alexei. Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.30.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.