To place Indigenous peoples at the center of Venezuelan history is not an act of inclusion for its own sake, but an analytical necessity.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Indigenous Venezuela beyond Marginality

Indigenous peoples have long occupied a paradoxical place in Venezuelan historical narratives. They are frequently acknowledged as part of the nation’s distant past yet treated as marginal to its modern history, reduced to demographic statistics or folkloric symbols rather than recognized as historical actors. In reality, Venezuela is home to at least fifty distinct Indigenous peoples, whose societies predate European contact by millennia and whose presence continues to shape the country’s cultural, environmental, and political landscape. Although Indigenous peoples today constitute a small percentage of the national population, their historical significance cannot be measured by numbers alone.1

Contemporary demographic estimates place Indigenous peoples at roughly 2.8 percent of Venezuela’s total population, with communities concentrated primarily in the southern states of Amazonas and Bolívar, the eastern region of Delta Amacuro, and the western state of Zulia.2 This geographic distribution reflects long-standing patterns of settlement shaped by rivers, forests, savannas, and coastal zones rather than by the administrative boundaries of the modern state. The concentration of Indigenous populations in border and peripheral regions has often reinforced their political marginalization, yet it has also enabled cultural continuity by limiting the reach of colonial and republican institutions.3

The diversity of Indigenous Venezuela is striking. Linguistic families such as Arawakan, Cariban, and Yanomaman encompass societies with distinct cosmologies, subsistence strategies, and social structures. Groups such as the Wayuu of the Guajira Peninsula developed semi-nomadic pastoral economies and cross-border identities, while riverine peoples like the Warao organized their lives around the waterways of the Orinoco Delta.4 In the southern interior, the Pemón linked their mythology to the dramatic tepui landscapes of the Gran Sabana, and the Yanomami maintained forest-based lifeways that limited sustained outside contact well into the twentieth century. These differences underscore that Indigenous Venezuela has never been culturally uniform, but instead deeply regional and environmentally grounded.

Colonial conquest and republican nation-building profoundly altered Indigenous societies, yet they did not erase them. Disease, missionization, forced labor, and land dispossession inflicted catastrophic losses, but many communities adapted through mobility, resistance, and selective engagement with colonial power.5 The survival of Indigenous peoples into the modern era challenges narratives of disappearance that still linger in popular and political discourse. Indigenous history in Venezuela is not confined to a “pre-contact” past but extends through conquest, independence, and the rise of extractive economies that reshaped the country in the twentieth century.6

To move beyond marginality, Indigenous history must be integrated into the broader history of Venezuela rather than treated as an appendix to it. Indigenous peoples were not merely obstacles to colonization or victims of modernization; they were active participants in regional economies, frontier politics, and environmental stewardship. Recognizing this continuity reframes Venezuelan history itself, revealing a nation built not only on colonial institutions and oil wealth, but also on the enduring presence of its first peoples.7

Deep History: Indigenous Societies before European Contact

Long before European arrival, the territory that would become Venezuela was inhabited by Indigenous societies whose histories stretched back thousands of years. Archaeological evidence indicates sustained human presence as early as the late Pleistocene, with populations adapting to a wide range of environments including coastal zones, river valleys, savannas, and tropical forests.8 These early societies were not static bands of foragers, but dynamic communities whose technologies, settlement patterns, and subsistence strategies evolved in response to environmental change and interregional contact.

By the first millennium BCE, many Indigenous groups practiced mixed subsistence economies combining hunting, fishing, gathering, and horticulture. Root crops such as manioc formed the agricultural backbone of numerous societies, particularly in lowland and riverine regions, while maize cultivation was more prominent in western and highland areas.9 Agricultural production supported semi-sedentary villages, population growth, and increasingly complex social organization. Trade networks connected communities across ecological zones, facilitating the exchange of foodstuffs, stone tools, ceramics, and ritual objects.10

Linguistic and cultural diversity reflected these deep regional adaptations. The major language families present in pre-contact Venezuela ( Arawakan, Cariban, and Chibchan) corresponded broadly, though not rigidly, to geographic and ecological zones. Arawakan-speaking peoples were widely distributed along river systems and coastal areas, while Cariban-speaking groups expanded across the Guiana Shield and eastern lowlands through processes of migration and conflict.11 These movements were not random but tied to access to resources, trade routes, and political power.

Social organization varied significantly among Indigenous societies. Some groups formed relatively small, kin-based communities, while others developed larger, more hierarchical structures centered on regional chiefs. Political authority was often situational and relational rather than coercive, grounded in ritual knowledge, mediation skills, and control over exchange networks.12 Warfare occurred but was typically limited in scale and embedded within systems of alliance and reciprocity. Violence was not the defining feature of Indigenous life, contrary to early colonial portrayals.

Cosmology and environmental knowledge shaped every aspect of Indigenous society. Landscapes were understood not merely as physical spaces but as animated worlds inhabited by spirits, ancestors, and transformative beings. Oral traditions linked origin stories to specific rivers, mountains, forests, and, in the case of the Guiana highlands, the tepui formations that dominated the horizon.13 This cosmological grounding reinforced sustainable land-use practices, embedding ecological stewardship within ritual and myth rather than abstract regulation.

By the eve of European contact, Indigenous Venezuela was characterized by diversity, resilience, and interconnection. These societies were neither isolated nor primitive. They were historically situated peoples engaged in long-term processes of adaptation, migration, and cultural exchange. Recognizing this deep history is essential, because it dispels the myth that Indigenous societies were timeless or undeveloped prior to conquest. Instead, they were active participants in shaping the human geography of northern South America long before European intervention disrupted these trajectories.14

Geography and Diversity: Indigenous Peoples of Venezuela

Overview

Venezuela’s Indigenous diversity is inseparable from its geography. Rainforests, savannas, deserts, river deltas, lakes, and highland plateaus created distinct ecological zones that shaped subsistence strategies, social organization, and cosmology. Indigenous societies did not develop in isolation from these environments but in active relationship with them, producing cultural variation rooted in place rather than in a single, uniform “Indigenous” experience.15 Regional specialization, mobility, and environmental knowledge formed the basis of survival and identity long before modern political borders imposed artificial divisions on Indigenous territories.

Northern and Western Regions

The Indigenous peoples of northern and western Venezuela developed lifeways adapted to arid zones, coastal ecosystems, and inland lakes. The Wayuu, the most populous Indigenous group in the country, inhabit the Guajira Peninsula in Zulia state, a semi-desert region extending across the border into Colombia. Their society is organized around matrilineal clans, pastoralism, fishing, and long-distance trade networks.16 Wayuu weaving traditions, particularly the production of hammocks and bags, carry social and symbolic meaning tied to lineage, status, and cosmology rather than serving merely as decorative arts.17 Their cross-border presence reflects precolonial territorial patterns that predate the modern nation-state.

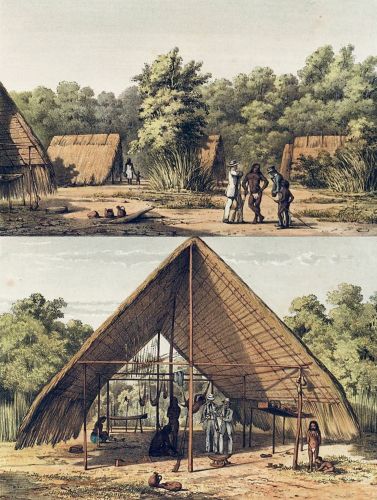

Also in Zulia are the Añú, an Arawakan-speaking people historically associated with Lake Sinamaica. The Añú are known for constructing palafitos, stilt houses built directly over the water, which allowed close integration with aquatic resources. Spanish observers encountered these settlements early, giving rise to the name “Venezuela,” or “Little Venice.”18 Despite their early visibility, the Añú experienced severe marginalization through missionization, land loss, and environmental degradation, yet elements of their lake-based culture persist into the present.19

Eastern and Delta Regions

In eastern Venezuela, the Orinoco Delta shaped the development of the Warao, whose name is often translated as “boat people.” The delta’s complex network of rivers, mangroves, and islands necessitated a water-centered mode of life in which canoes functioned as primary means of transportation, trade, and subsistence.20 Fishing, gathering, and small-scale horticulture sustained dispersed settlements, while social organization emphasized flexibility and mobility in response to seasonal flooding.

Warao cosmology and oral tradition are deeply embedded in delta landscapes, linking origin stories to rivers and forest spaces. This environmental integration fostered resilience but also heightened vulnerability to modern disruptions.21 In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, oil development, deforestation, and public health crises disproportionately affected Warao communities, illustrating how ecological dependence can become a liability under extractive pressure.22

Southern Interior and Amazonian Regions

The southern interior of Venezuela contains some of the country’s most culturally and linguistically diverse Indigenous populations. In Bolívar state, the Pemón inhabit the Gran Sabana, a highland savanna dominated by tepui formations. Pemón society is divided into three principal dialect groups (Arekuna, Kamarakoto, and Taurepang) each associated with particular territories and ritual traditions.23 Pemón cosmology ties social order to the landscape itself, with tepuis understood as ancestral beings or sites of primordial transformation rather than inert geological features.24

Further south, along the border with Brazil, the Yanomami represent one of the most isolated Indigenous populations in South America. Living in forest-based settlements known as shabonos, the Yanomami rely on hunting, horticulture, and foraging within a cosmological framework that emphasizes balance between human and non-human worlds.25 Limited sustained contact with outsiders until the late twentieth century allowed cultural continuity, but also left Yanomami communities especially vulnerable to disease, illegal mining, and territorial intrusion once contact intensified.26

Eastern Lowlands and Cariban Heritage

The Kariña, also known as Kali’na, occupy parts of eastern Venezuela, including Anzoátegui and Monagas states. A Cariban-speaking people, the Kariña historically engaged in agriculture, fishing, and regional warfare, maintaining wide-ranging networks across northern South America.27 Their resistance to colonial encroachment was prolonged, and elements of their language and identity survived despite displacement and assimilation pressures during the republican period.28

Conclusion

These regional cases demonstrate that Indigenous Venezuela cannot be understood through a single cultural model. Diversity emerged from long-term engagement with distinct environments, producing societies that were adaptive, interconnected, and resilient. Geographic specialization shaped not only subsistence strategies but political organization, cosmology, and historical experience. Recognizing this diversity is essential to understanding both the endurance of Indigenous cultures and the uneven impact of colonialism, state-building, and modern extraction across Venezuela’s Indigenous landscapes.29

Encounter and Conquest: Indigenous Peoples under Spanish Rule

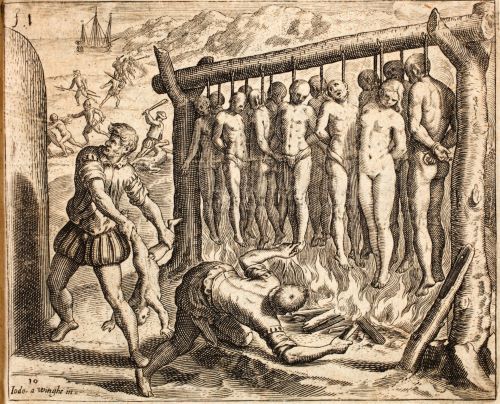

Spanish arrival in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries marked a violent rupture in Indigenous Venezuela. Initial contact varied widely by region, shaped by geography, population density, and colonial priorities. Coastal and riverine societies were drawn early into imperial networks through slaving raids, missionization, and extractive demands, while peoples of the southern interior encountered sustained colonial pressure much later. Disease proved the most devastating force, spreading rapidly along contact routes and precipitating demographic collapse that reshaped entire regions within decades.30

Colonial exploitation took institutional form through systems that subordinated Indigenous labor and land to imperial authority. Encomiendas and repartimientos imposed forced labor and tribute obligations, while missions sought to reorganize Indigenous life around Christian doctrine and sedentary settlement. In western Venezuela and along major waterways, mission complexes became instruments of both spiritual conversion and economic extraction, drawing Indigenous peoples into colonial markets while undermining existing social structures.31 The cumulative effect was not uniform assimilation but fragmentation, as communities responded differently to coercion, accommodation, and flight.

Resistance was persistent and multifaceted. Armed confrontation occurred in several regions, particularly where Indigenous groups could mobilize alliances or retreat into difficult terrain. In the Guajira Peninsula, the Wayuu leveraged mobility, pastoralism, and access to firearms through trade to resist sustained Spanish control well into the eighteenth century, maintaining a degree of autonomy unmatched elsewhere in the colony.32 Elsewhere, resistance took less visible forms, including work slowdowns, selective conversion, and the preservation of ritual practices beneath the surface of Christian observance.33

Geography profoundly shaped colonial outcomes. The Orinoco Delta, the Guiana Highlands, and the Amazonian interior limited Spanish penetration, allowing groups such as the Warao, Pemón, and Yanomami to avoid prolonged colonial administration. Missionary presence did expand into these regions, but logistical constraints and Indigenous mobility curtailed effective control.34 These frontier zones became spaces of negotiated power, where colonial authority remained intermittent and contested rather than absolute.

Colonial representations of Indigenous peoples further distorted historical understanding. Spanish chroniclers often depicted Indigenous societies as either noble innocents or violent obstacles to civilization, narratives that justified conquest and dispossession. Such portrayals obscured the complexity of Indigenous political organization and the rational strategies communities employed to survive under colonial pressure.35 These narratives would later inform republican-era policies that treated Indigenous peoples as remnants of a vanished past rather than as living societies with territorial claims.

By the end of the colonial period, Indigenous Venezuela had been irrevocably altered but not erased. Population losses were severe, territories were fragmented, and social systems were disrupted. Yet many communities endured through adaptation, retreat, and selective engagement with colonial institutions.36 The Spanish conquest did not conclude Indigenous history. It reshaped it, embedding survival within a landscape of coercion that would persist, in altered forms, into the republican era.

Indigenous Peoples in the Republican Era

The collapse of Spanish rule in the early nineteenth century did not bring meaningful liberation for Indigenous peoples in Venezuela. Independence reconfigured political authority, but it largely preserved colonial assumptions about land, citizenship, and progress. Republican elites framed the new nation as culturally homogeneous, equating modernity with mestizaje and viewing Indigenous communities as vestiges of a backward past to be absorbed or erased.37 Legal equality was proclaimed in principle, yet Indigenous peoples were rarely recognized as collective subjects with distinct rights, rendering them politically invisible within the emerging republic.

Land dispossession accelerated during the republican period. Liberal reforms dismantled communal landholding systems in favor of private property regimes that privileged large landowners and commercial agriculture. Indigenous territories, often lacking formal titles recognized by the state, were reclassified as vacant or underutilized lands and transferred to non-Indigenous elites.38 This process fractured traditional subsistence systems and forced many Indigenous communities into wage labor, debt peonage, or marginal ecological zones where survival became increasingly precarious.

State-building and economic expansion further deepened Indigenous marginalization. The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw the expansion of coffee cultivation, cattle ranching, and later oil development, all of which encroached upon Indigenous lands without consultation or compensation. In western Venezuela, oil extraction intensified pressures on Wayuu and Añú territories, while in the south, exploratory expeditions and missionary activity extended state presence into previously autonomous regions.39 These incursions framed Indigenous peoples as obstacles to development rather than as stakeholders in the nation’s future.

Despite these pressures, Indigenous communities did not disappear into the republican order. Resistance continued through localized uprisings, cross-border mobility, and the maintenance of cultural practices outside state institutions. Some groups negotiated limited recognition through missions or regional authorities, while others avoided sustained contact altogether.40 The republican era thus reproduced colonial patterns of exclusion under new ideological banners, embedding Indigenous survival within a national project that proclaimed unity while systematically denying Indigenous autonomy and historical agency.

Modern Pressures: Extraction, Borders, and State Power

The twentieth century introduced pressures on Indigenous Venezuela that differed in scale and intensity from those of earlier periods. The consolidation of state authority, coupled with the expansion of extractive industries, brought Indigenous territories into direct confrontation with national and global economic forces. Oil, mining, hydroelectric projects, and large-scale infrastructure development transformed Indigenous lands into strategic assets, often without recognition of existing communities or consultation regarding their futures.41 These projects were framed as symbols of national progress, rendering Indigenous presence invisible or expendable within developmental discourse.

Oil extraction proved especially disruptive in western Venezuela. In Zulia state, the rapid growth of petroleum infrastructure reshaped landscapes inhabited by the Wayuu and Añú, contaminating water sources, fragmenting grazing lands, and undermining subsistence practices tied to mobility and fishing.42 While oil wealth fueled national modernization, Indigenous communities bore disproportionate environmental and social costs, receiving little material benefit from the industry that transformed their homelands. The logic of extraction subordinated Indigenous rights to the imperatives of revenue and state power.

In the southern interior, mining supplanted oil as the dominant extractive threat. Gold and mineral exploitation expanded dramatically in Bolívar and Amazonas states, particularly in regions overlapping with Pemón and Yanomami territories.43 State-sanctioned mining initiatives and illegal operations alike brought deforestation, mercury contamination, and armed actors into previously remote areas. These incursions destabilized Indigenous governance structures and exposed communities to disease and violence, compounding vulnerabilities rooted in geographic isolation.

Borders further complicated Indigenous survival. Many Indigenous peoples occupied territories that predated and transcended national boundaries, yet modern border regimes restricted movement and redefined long-standing social networks as security concerns. In the Guajira Peninsula, Wayuu mobility across the Venezuela–Colombia border conflicted with state efforts to regulate trade and migration.44 In the Amazonian south, militarization tied to border security and resource control intensified surveillance and intervention in Indigenous life, often justified by claims of sovereignty and national defense.

These modern pressures revealed the enduring tension between Indigenous territoriality and the state’s extractive vision. Development policies treated land as an economic resource rather than as a living cultural space, reducing Indigenous claims to obstacles to be managed or removed.45 The cumulative effect was not merely environmental degradation but a reconfiguration of power, in which Indigenous communities faced the challenge of survival within a political economy that valued territory for what could be extracted from it, not for the societies that sustained it.

Rights, Recognition, and Indigenous Resistance

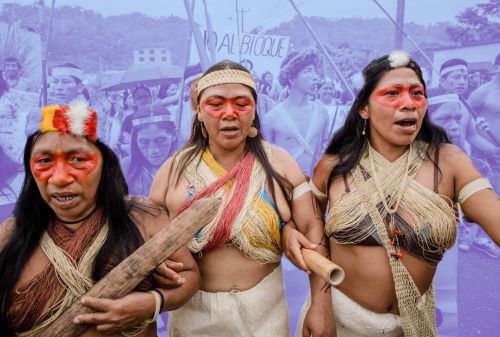

By the late twentieth century, Indigenous peoples in Venezuela increasingly articulated their struggles in the language of rights rather than survival alone. Decades of dispossession and exclusion gave rise to Indigenous movements that demanded recognition as collective subjects with territorial, cultural, and political claims. These efforts were shaped by broader Latin American currents that reframed Indigenous identity as a basis for citizenship rather than an obstacle to national unity.46 In Venezuela, this shift marked a departure from earlier assimilationist policies that treated Indigenous peoples as populations to be absorbed into a homogenized republic.

Legal recognition advanced most visibly with constitutional reform. The 1999 constitution acknowledged the multicultural character of the Venezuelan nation and formally recognized Indigenous peoples’ rights to land, language, political participation, and cultural autonomy.47 This framework represented a significant symbolic break from centuries of legal invisibility, affirming Indigenous identity as compatible with national belonging. Yet constitutional recognition did not automatically translate into material protection. Implementation lagged, land demarcation proceeded unevenly, and state institutions retained discretionary power over Indigenous territories.

Indigenous resistance adapted to these conditions through a combination of political engagement and local mobilization. Indigenous organizations pursued representation in regional and national assemblies, while communities defended land claims through protests, legal challenges, and appeals to international bodies.48 In areas affected by mining and infrastructure projects, resistance often centered on environmental protection, linking Indigenous rights to broader concerns about ecological destruction and public health. These struggles highlighted the limits of recognition without enforcement.

Despite constitutional advances, Indigenous peoples remained vulnerable to shifting political priorities. Economic crisis and state centralization eroded institutional safeguards, while extractive imperatives increasingly overrode Indigenous consultation.49 Resistance persisted, but it operated within a narrowing political space, constrained by repression, resource scarcity, and weakened legal mechanisms. The struggle for rights thus remained unfinished, revealing recognition not as an endpoint, but as a contested terrain in which Indigenous survival continued to depend on organized resistance and strategic engagement with power.

Contemporary Challenges and Survival

In the early twenty-first century, Venezuela’s broader political and economic collapse has fallen with particular severity on Indigenous communities. Long-standing structural inequalities intensified as inflation, food scarcity, and the breakdown of public services eroded already limited access to healthcare, education, and state support. Indigenous peoples, especially those in remote regions, faced heightened vulnerability as supply chains collapsed and state institutions retreated from peripheral territories.50 What emerged was not a new crisis, but an acceleration of pressures rooted in centuries of marginalization.

Health crises exposed the fragility of Indigenous survival under these conditions. Malaria, measles, tuberculosis, and malnutrition surged in Indigenous regions, particularly in the Amazonian south, where medical infrastructure was minimal even before the national collapse.51 For groups such as the Yanomami, illegal mining brought not only environmental contamination but also infectious disease and violence, overwhelming community-based health practices. The erosion of preventive care transformed manageable illnesses into existential threats.

Food insecurity compounded these dangers. Disruption of traditional subsistence patterns through environmental degradation, combined with the collapse of national food distribution systems, left many Indigenous communities dependent on irregular aid or cross-border movement for survival.52 Riverine and forest-based economies that once provided resilience were undermined by pollution, deforestation, and restricted mobility. Hunger thus became both a material condition and a political outcome of exclusion.

Migration emerged as a survival strategy. Indigenous peoples joined the broader Venezuelan exodus, often moving across borders into Colombia, Brazil, and Guyana. For some groups, such as the Wayuu, cross-border movement aligned with historical patterns of mobility, while for others it represented a rupture with land-based identities.53 Migration frequently exposed Indigenous migrants to exploitation, statelessness, and discrimination, replicating patterns of vulnerability beyond Venezuela’s borders.

Yet survival has not been passive. Indigenous communities have mobilized mutual aid networks, cultural revitalization efforts, and alliances with international organizations to confront these challenges.54 Language preservation, territorial defense, and environmental advocacy became tools of endurance as much as expressions of identity. Contemporary Indigenous survival in Venezuela thus reflects both extreme precarity and persistent agency, revealing resilience not as romantic endurance but as a continual struggle against conditions that threaten collective existence.

Conclusion: Continuity, Resilience, and Historical Centrality

The history of Indigenous peoples in Venezuela reveals a continuity that defies narratives of disappearance and marginality. From deep pre-contact societies through conquest, republican exclusion, extractive expansion, and contemporary crisis, Indigenous communities have remained present as historical actors rather than passive remnants. Their survival was never guaranteed, nor was it accidental. It emerged from adaptive strategies grounded in land, social organization, and cultural knowledge that allowed endurance under shifting regimes of power.55 Recognizing this continuity challenges national histories that treat Indigenous peoples as belonging only to an ancient past rather than to the living present of the Venezuelan state.

Resilience, however, should not be misunderstood as immunity. Indigenous endurance came at enormous cost, including demographic collapse, territorial loss, and systemic exclusion. The capacity to survive did not eliminate vulnerability; it merely reshaped it. Colonial violence, republican dispossession, and modern extraction each produced distinct forms of precarity that accumulated rather than replaced one another.56 Indigenous resilience thus reflects sustained struggle within hostile political and economic structures, not harmonious coexistence with them.

Indigenous history also exposes the limits of state-centered narratives of progress. Venezuelan nation-building, often framed through independence, oil wealth, and modernization, repeatedly advanced at the expense of Indigenous autonomy. Legal recognition and constitutional reform altered the language of governance but rarely transformed its material priorities.57 Indigenous peoples remained subject to development models that valued territory for extraction and control rather than for the societies rooted within it. Their resistance therefore illuminates not only Indigenous history but the contradictions embedded in the Venezuelan state itself.

To place Indigenous peoples at the center of Venezuelan history is not an act of inclusion for its own sake, but an analytical necessity. Indigenous societies shaped landscapes, economies, and cultural systems long before European arrival and continue to confront the consequences of national and global forces that depend on their lands.58 A historically grounded understanding of Venezuela cannot be complete without acknowledging Indigenous peoples as foundational to its past and indispensable to its future. Their history is not ancillary to the nation’s story. It is inseparable from it.’

Appendix

Footnotes

- Fernando Coronil, The Magical State: Nature, Money, and Modernity in Venezuela (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 73–90.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE), XIV Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda: Población Indígena (Caracas: INE, 2011).

- Nelly Arvelo-Jiménez, “Indigenous Peoples and the State in Venezuela,” in Indigenous Peoples and Democracy in Latin America, ed. Donna Lee Van Cott (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994), 155–178.

- Johannes Wilbert and Karin Simoneau, eds., Folk Literature of the Pemón (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1990).

- Jonathan D. Hill and Fernando Santos-Granero, eds., Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002).

- David J. Sweet, A Rich Realm of Nature Destroyed: The Middle Amazon Valley, 1640–1750. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1974.

- Miguel Ángel Perera, Los pueblos indígenas de Venezuela (Caracas: Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, 2004).

- Tom D. Dillehay, The Settlement of the Americas: A New Prehistory (New York: Basic Books, 2000), 179–205.

- Betty J. Meggers, Amazonia: Man and Culture in a Counterfeit Paradise (Chicago: Aldine, 1971), 71–96.

- Anna C. Roosevelt, Amazonian Indians from Prehistory to the Present: Anthropological Perspectives (Phoenix: University of Arizona Press, 1994): 118–147.

- Hill and Santos-Granero, eds., Comparative Arawakan Histories, 1–38.

- Robert L. Carneiro, “The Chiefdom: Precursor of the State,” in The Transition to Statehood in the New World, ed. Grant D. Jones and Robert R. Kautz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 37–79.

- Wilbert and Simoneau, eds., Folk Literature of the Pemón.

- Roosevelt, Amazonian Indians from Prehistory to the Present, 248–276.

- Berta E. Pérez , “Rethinking Venezuelan Anthropology,” Ethnohistory 47:3-4 (2000), 513-533.

- Perera, Los pueblos indígenas de Venezuela, 97–115.

- Johannes Wilbert, Wayuu Cosmology and Weaving Traditions (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1987), 42–68.

- Tomás Straka, La república fragmentada: Claves para entender a Venezuela (Caracas: Editorial Alfa, 2013), 21–24.

- Perera, Los pueblos indígenas de Venezuela, 121–132.

- Juan Luis Rodríguez, “Language and Revolutionary Magic in the Orinoco Delta,” The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 30:3 (2021).

- Johannes Wilbert, Warao Oral Literature (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1993), 11–36.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Indigenous Peoples and Development in Venezuela (Caracas: UNDP, 2010).

- Audrey Butt Colson, Land: Its Occupation, Management, Use and Conceptualization: The Case of the Akawaio and Arekuna of the Upper Mazaruni District, Guyana, (Louisville: Last Refuge, 2009), 55–79.

- Wilbert and Simoneau, eds., Folk Literature of the Pemón.

- Napoleon A. Chagnon, Yanomamö: The Fierce People, 6th ed. (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 2013), 27–51.

- Terry Devine Guzman, Native and National in Brazil: Indigeneity after Independence, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 213–238.

- Stephan Lenik, “Carib as a Colonial Category: Comparing Ethnohistoric and Archaeological Evidence from Dominica, West Indies,” Ethnohistory 59, no. 1 (2012): 79-107.

- Perera, Los pueblos indígenas de Venezuela, 203–218.

- Pérez , “Rethinking Venezuelan Anthropology,” 513-533.

- Noble David Cook, Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 190–224.

- Sweet, “A Rich Realm of Nature Destroyed: The Middle Amazon Valley, 1640–1750,” 469–500.

- Jorge L. Pérez, La resistencia guajira a la conquista española (Maracaibo: Universidad del Zulia, 1994), 61–89.

- James Lockhart and Stuart B. Schwartz, Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 91–118.

- Charles C. Mann, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 312–337.

- Rolena Adorno, The Polemics of Possession in Spanish American Narrative (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 143–172.

- Perera, Los pueblos indígenas de Venezuela, 145–176.

- Arvelo-Jiménez, “Indigenous Peoples and the State in Venezuela,” 155–160.

- Perera, Los pueblos indígenas de Venezuela, 177–196.

- Coronil, The Magical State, 91–110.

- Charles R. Hale, “Does Multiculturalism Menace? Governance, Cultural Rights, and the Politics of Identity in Latin America,” Journal of Latin American Studies 34, no. 3 (2002): 485–524.

- Coronil, The Magical State, 111–145.

- Perera, Los pueblos indígenas de Venezuela, 219–242.

- Brian S. McBeth, Juan Vicente Gómez and the Oil Companies in Venezuela, 1908–1935 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 201–218; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Environmental Impacts of Mining in the Amazon Basin (Nairobi: UNEP, 2013).

- Gary Hytrek. “Introduction: Globalization and Social Change in Latin America,” Latin American Perspectives 29, no. 5 (2002): 3-6.

- Terry Lynn Karl, The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 185–204.

- Donna Lee Van Cott, The Friendly Liquidation of the Past: The Politics of Diversity in Latin America (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000), 69–96.

- Constitución de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela (1999), Articles 119–126.

- Charles R. Hale, “Activist Research v. Cultural Critique: Indigenous Land Rights and the Contradictions of Politically Engaged Anthropology,” Cultural Anthropology 21, no. 1 (2006): 96–120.

- United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Report on the Situation of Indigenous Peoples in Venezuela (Geneva: United Nations Human Rights Council, 2016).

- International Crisis Group, Venezuela’s Humanitarian Emergency (Brussels: International Crisis Group, 2019).

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), Health Situation in Indigenous Communities of Venezuela (Washington, DC: PAHO, 2018).

- World Food Programme (WFP), Venezuela Food Security Assessment (Rome: WFP, 2019).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Indigenous Peoples and the Venezuelan Displacement Crisis (Geneva: UNHCR, 2020).

- Amnesty International, Indigenous Peoples at Risk: Venezuela (London: Amnesty International, 2021).

- Perera, Los pueblos indígenas de Venezuela, 301–318.

- Pérez , “Rethinking Venezuelan Anthropology,” 513-533.

- Van Cott, The Friendly Liquidation of the Past, 171–194.

- United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Report on the Situation of Indigenous Peoples in Venezuela (Geneva: United Nations Human Rights Council, 2016).

Bibliography

- Adorno, Rolena. The Polemics of Possession in Spanish American Narrative. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Amnesty International. Indigenous Peoples at Risk: Venezuela. London: Amnesty International, 2021.

- Arvelo-Jiménez, Nelly. “Indigenous Peoples and the State in Venezuela.” In Indigenous Peoples and Democracy in Latin America, edited by Donna Lee Van Cott, 155–178. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994.

- Butt Colson, Audrey. Land: Its Occupation, Management, Use and Conceptualization: The Case of the Akawaio and Arekuna of the Upper Mazaruni District, Guyana. Louisville: Last Refuge, 2009.

- Carneiro, Robert L. “The Chiefdom: Precursor of the State.” In The Transition to Statehood in the New World, edited by Grant D. Jones and Robert R. Kautz, 37–79. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

- Chagnon, Napoleon A. Yanomamö: The Fierce People. 6th ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 2013.

- Constitución de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela. 1999.

- Cook, Noble David. Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Coronil, Fernando. The Magical State: Nature, Money, and Modernity in Venezuela. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

- Dillehay, Tom D. The Settlement of the Americas: A New Prehistory. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

- Guzman, Terry Devine. Native and National in Brazil: Indigeneity after Independence. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

- Hale, Charles R. “Does Multiculturalism Menace? Governance, Cultural Rights, and the Politics of Identity in Latin America.” Journal of Latin American Studies 34, no. 3 (2002): 485–524.

- Hale, Charles R. “Activist Research v. Cultural Critique: Indigenous Land Rights and the Contradictions of Politically Engaged Anthropology.” Cultural Anthropology 21, no. 1 (2006): 96–120.

- Hill, Jonathan D., and Fernando Santos-Granero, eds. Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

- Hytrek, Gary. “Introduction: Globalization and Social Change in Latin America.” Latin American Perspectives 29, no. 5 (2002): 3-6.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). XIV Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda: Población Indígena. Caracas: INE, 2011.

- International Crisis Group. Venezuela’s Humanitarian Emergency. Brussels: International Crisis Group, 2019.

- Karl, Terry Lynn. The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

- Lenik, Stephan. “Carib as a Colonial Category: Comparing Ethnohistoric and Archaeological Evidence from Dominica, West Indies.” Ethnohistory 59, no. 1 (2012): 79-107.

- Lockhart, James, and Stuart B. Schwartz. Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Mann, Charles C. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus. New York: Vintage Books, 2005.

- McBeth, Brian S. Juan Vicente Gómez and the Oil Companies in Venezuela, 1908–1935. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Meggers, Betty J. Amazonia: Man and Culture in a Counterfeit Paradise. Chicago: Aldine, 1971.

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Health Situation in Indigenous Communities of Venezuela. Washington, DC: PAHO, 2018.

- Perera, Miguel Ángel. Los pueblos indígenas de Venezuela. Caracas: Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, 2004.

- Pérez, Berta E. “Rethinking Venezuelan Anthropology.” Ethnohistory 47:3-4 (2000), 513-533.

- Pérez, Jorge L. La resistencia guajira a la conquista española. Maracaibo: Universidad del Zulia, 1994.

- Rodríguez, Juan Luis. “Language and Revolutionary Magic in the Orinoco Delta.” The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 30:3 (2021).

- Roosevelt, Anna C. Amazonian Indians from Prehistory to the Present: Anthropological Perspectives. Phoenix: University of Arizona Press, 1994.

- Straka, Tomás. La república fragmentada: Claves para entender a Venezuela. Caracas: Editorial Alfa, 2013.

- Sweet, David J. A Rich Realm of Nature Destroyed: The Middle Amazon Valley, 1640–1750. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1974.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Indigenous Peoples and Development in Venezuela. Caracas: UNDP, 2010.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Environmental Impacts of Mining in the Amazon Basin. Nairobi: UNEP, 2013.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Indigenous Peoples and the Venezuelan Displacement Crisis. Geneva: UNHCR, 2020.

- United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Report on the Situation of Indigenous Peoples in Venezuela. Geneva: United Nations Human Rights Council, 2016.

- Van Cott, Donna Lee. The Friendly Liquidation of the Past: The Politics of Diversity in Latin America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000.

- Wilbert, Johannes. Wayuu Cosmology and Weaving Traditions. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1987.

- Wilbert, Johannes. Warao Oral Literature. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1993.

- Wilbert, Johannes, and Karin Simoneau, eds. Folk Literature of the Pemón. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1990.

- World Food Programme (WFP). Venezuela Food Security Assessment. Rome: WFP, 2019.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.23.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.