Tea was traded as currency, consumed as sustenance, elevated as ritual, and debated as medicine. Its journey reveals that the Silk Road was never only about goods.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Tea traveled the Silk Road as both leaf and legend. It was traded, gifted, consumed, and ritualized. It was never just a beverage. Along caravan routes, tea became currency, medicine, symbol, and solace. To trace its passage is to uncover how one plant shaped economies and defined cultural boundaries.

The Silk Road was more than trade; it was transmission. Silk, spices, jade, and horses all moved along its arteries, but tea is distinctive for the way it carried meaning as well as value. The leaf itself was transformed (pressed into bricks, boiled in butter, infused with salt) and in each form it absorbed local customs. What began in the mountains of southwest China became central to Tibetan ritual, Mongolian identity, and even Islamic debates over stimulants.

Origins of Tea in Ancient China

Early Use and Mythic Roots

Chinese tradition places the discovery of tea in the hands of Shennong, the divine farmer who tasted plants to test their effects.1 Whether mythical or not, early references frame tea as medicinal: a bitter infusion taken to cleanse the body and sharpen the senses.

Tea was not initially a drink of pleasure. It was bitter, functional, pragmatic. Only later did it slip from pharmacology into daily life. That transition mattered, because it turned tea into a cultural marker rather than a mere tonic.

Institutionalization of Tea Culture

By the Tang dynasty, tea was canonized. Poets wrote hymns to its flavor. The Chajing of Lu Yu, composed in the eighth century, elevated tea-drinking into a ritualized art.2 Tea houses flourished in cities, while monasteries cultivated tea both for income and meditation.

Sichuan and Fujian became the core of cultivation. Production was standardized, and tea began to travel, not yet across continents, but across provinces. Its identity shifted from local habit to imperial commodity.

Tea as a Commodity on the Silk Road

Trade Networks and Routes

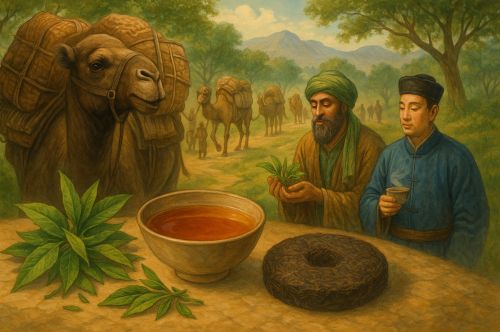

Caravans leaving China carried bolts of silk, ceramics, and tea. Tea was bundled into the same convoys as luxury goods, yet its role was unique. Unlike jade or silk, tea could not simply be displayed; it had to be consumed. This meant it entered daily life, changing habits wherever it arrived.

The great overland routes across the Gansu corridor, through Dunhuang, and into Central Asia carried bricks of tea westward. Maritime routes through the South China Sea and Indian Ocean carried it further still. Each path reshaped the leaf’s destiny.

Preservation and Transport

Tea was fragile, so traders pressed it into bricks. These could be stacked, carried by camel, and even used as currency. In Tibet, tea bricks were as valuable as silver.3 In Mongolia, they circulated as barter, exchanged for horses, wool, or labor. Portability made tea not just a drink but a unit of economic life.

Economic Value

The tea-horse trade defined much of Sino-Tibetan commerce. Chinese dynasties prized hardy Tibetan horses for military campaigns. In exchange, they sent tea; not luxury tea, but sturdy, compressed bricks designed for transport. The transaction was practical but layered with cultural consequence: horses for empire, tea for endurance.

Cultural Transfers and Adaptations

Tea in Central Asia

Central Asia turned tea into something new. In Tibet, it became butter tea: brewed strong, churned with yak butter and salt, producing a calorie-rich sustenance essential to high-altitude life. It was not delicate, not poetic, but functional and communal. Drinking butter tea bound monasteries, families, and rituals together.

Among Mongols, tea was similarly adapted. Milk teas emerged, consumed with meat-heavy diets, integrated into the rhythms of nomadic life. What began as a Chinese infusion of leaves became sustenance against cold winds and barren steppes.

Tea in the Islamic World

The Islamic encounter with tea was complex. Coffee would later dominate, but early Muslim travelers along the Silk Road described infusions of leaves used for refreshment and health. Tea entered hospitality rituals in some regions, though it remained less central than in Central Asia.

Sufis sometimes used stimulants to aid long vigils of prayer. Tea could be folded into this practice, though later Islamic scholars debated its status compared with coffee and wine. Tea never achieved the dominance in the Islamic heartlands that it enjoyed in Asia, but its presence reveals the breadth of its journey.

Tea and Medicine

Persian and Arab medical texts occasionally list teas among pharmacopoeias. The bitter infusion was prescribed for digestion, clarity, and balance. In these contexts, tea was a drug more than a delight, another entry in the trans-Eurasian circulation of remedies.4

Tea as a Vehicle of Cultural Exchange

Tea Ceremonies and Social Rituals

tea ceremony. Before mixing the tea the bowl is rinsed with fresh water. / Penn State, Flickr, Creative Commons

From Tang and Song China, tea-drinking spread as ritualized performance. Neighbors imitated, adapted, and localized. In Japan, tea ceremonies evolved into elaborate codes of civility. In Central Asia, communal bowls of tea created other forms of etiquette. Ritual attached itself to tea like scent to the leaf.

Tea and Identity

To drink tea was to mark oneself. In China, it became a marker of refined taste among elites. In Tibet, it defined communal belonging. In Mongolia, tea linked nomadic diets to shared culture. Tea’s versatility meant that it could signal elite refinement in one context, survival and solidarity in another.

Tea and Religion

Buddhism carried tea with it. Monks cultivated tea near monasteries, both to sustain themselves and to sell for revenue. More importantly, tea served as an aid to meditation, keeping practitioners alert during long hours of chanting and study. Tea thus fused the physiological with the spiritual, binding body and mind through ritualized consumption.5

Later Legacies and Global Trajectories

Tea’s Expansion Beyond the Silk Road

By the late medieval period, maritime networks carried tea further. Southeast Asian ports became nodes of distribution, and eventually European traders encountered the leaf. By the seventeenth century, Portuguese and Dutch merchants brought tea to Europe, igniting new chapters of cultural transfer.

Echoes of the Ancient Exchange

Even today, Central Asian tea-drinking practices retain echoes of these early transfers. Tibetan butter tea remains a ritual offering in monasteries. Mongolian milk tea is still served to guests as hospitality. These practices carry within them centuries of exchange, memory, and adaptation. The Silk Road may no longer exist as caravan route, but in the tea bowls of Lhasa and Ulaanbaatar, its history remains.

Conclusion

Tea’s passage along the Silk Road demonstrates how a commodity can become culture. It was traded as currency, consumed as sustenance, elevated as ritual, and debated as medicine. Its journey reveals that the Silk Road was never only about goods. It was about transformation. A bitter leaf, brewed differently in different lands, became a shared yet distinct symbol across Eurasia.

Appendix

Footnotes

- James A. Benn, Tea in China: A Religious and Cultural History (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2015), 12–15.

- Lu Yu, The Classic of Tea (Chajing), trans. Francis Ross Carpenter (Boston: Little, Brown, 2019), 3–5.

- Xinru Liu, The Silk Road in World History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 68.

- Peter E. Pormann and Emilie Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), 142.

- Francesca Bray, Technology and Gender: Fabrics of Power in Late Imperial China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 88–90.

Bibliography

- Benn, James A. Tea in China: A Religious and Cultural History. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2015.

- Bray, Francesca. Technology and Gender: Fabrics of Power in Late Imperial China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

- Liu, Xinru. The Silk Road in World History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Lu Yu. The Classic of Tea: The World’s First Treatise on Tea Culture. Translated by Francis Ross Carpenter. Boston: Little, Brown, 2019.

- Pormann, Peter E., and Emilie Savage-Smith. Medieval Islamic Medicine. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.12.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.