The Roman experience demonstrates that the repression of speech rarely begins with overt brutality. It begins with anxiety.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Speech as Threat in Authoritarian Systems

Authoritarian systems do not primarily fear weapons, conspiracies, or even rebellion. They fear speech that reshapes perception, because perception is the substrate of legitimacy. Armies can suppress bodies, but words reorganize meaning, memory, and expectation. Across history, rulers have repeatedly tolerated sporadic violence more readily than sustained commentary, ridicule, or narrative reframing that renders power contingent rather than inevitable. Speech becomes dangerous not when it is demonstrably false, but when it is socially effective, when it circulates, persuades, and embeds itself in everyday interpretation. Satire, rumor, and informal political commentary operate precisely at this level. They bypass official channels, resist direct refutation, and spread horizontally rather than hierarchically. For regimes dependent on authority rather than consent, this form of communication is uniquely corrosive. It teaches subjects not what to think, but how to see power differently, and once perception shifts, obedience becomes unstable even without organized resistance.

In authoritarian contexts, censorship rarely presents itself as censorship. Instead, it is framed as protection: of public morals, social harmony, religious values, or civic peace. The language of repression is almost always defensive. Power claims fragility. Speech is recast not as critique, but as disorder. This rhetorical move allows rulers to criminalize dissent while maintaining the appearance of legality. The danger, historically, is not that law disappears, but that law becomes the instrument through which silence is enforced. When speech is regulated in the name of order, repression no longer looks exceptional. It becomes routine, procedural, and normalized.

The Roman Empire offers one of the earliest and most revealing examples of this process. Rome did not possess a free press in the modern sense, nor did it require one to fear public opinion. Information circulated through recitations, satire, rumor, graffiti, and short written texts that functioned much like pamphlets. These forms shaped reputation, legitimacy, and memory in a society where honor and public standing were political currencies. Roman authorities understood this intuitively. Control of speech meant control of how power was seen, remembered, and judged. As imperial authority consolidated, commentary that challenged official narratives was increasingly framed as a danger to public order rather than a feature of civic life.

What follows argues that the Roman suppression of satirists and political commentators was not an aberration, but an early expression of a durable authoritarian pattern that recurs whenever power becomes anxious about legitimacy. Roman emperors did not silence critics because satire was trivial, but because it was effective. By criminalizing dissenting speech through charges of impiety, immorality, or treason, imperial authority converted cultural influence into political threat and placed narrative control under legal supervision. The importance of this history lies not in drawing crude equivalence between ancient and modern systems, but in identifying structural continuity. When rulers redefine criticism as destabilization, when law is mobilized to punish those who shape public understanding, and when “order” becomes the supreme justification for silence, the erosion of press freedom is already underway. Rome demonstrates that authoritarianism often advances quietly, not through mass terror at first, but through the disciplined management of words, voices, and memory itself.

The Roman Information Environment: Rumor, Pamphlet, and Public Opinion

The Roman Empire did not require printing presses or newspapers to develop a vibrant and politically consequential information environment. Communication operated through dense social networks that combined oral transmission, performative reading, handwritten texts, and visual inscription. Rumor moved rapidly along roads, through markets, and within households. Political meaning was generated not by centralized publication, but by repetition, interpretation, and social reinforcement. In such a system, information did not need to be formally verified to be influential. It needed only to be plausible, timely, and resonant with existing anxieties or expectations.

Oral circulation formed the backbone of Roman public opinion. Speeches delivered in the Forum, gossip exchanged in bathhouses, and stories retold at dinners created a continuous feedback loop between elites and non-elites. Senators and equestrians monitored rumor carefully, understanding that reputations could be made or destroyed without a single official statement. This environment rewarded wit, memory, and narrative skill. It also ensured that attempts at suppression were never total. Once spoken, words could not be recalled, only contested or punished after the fact.

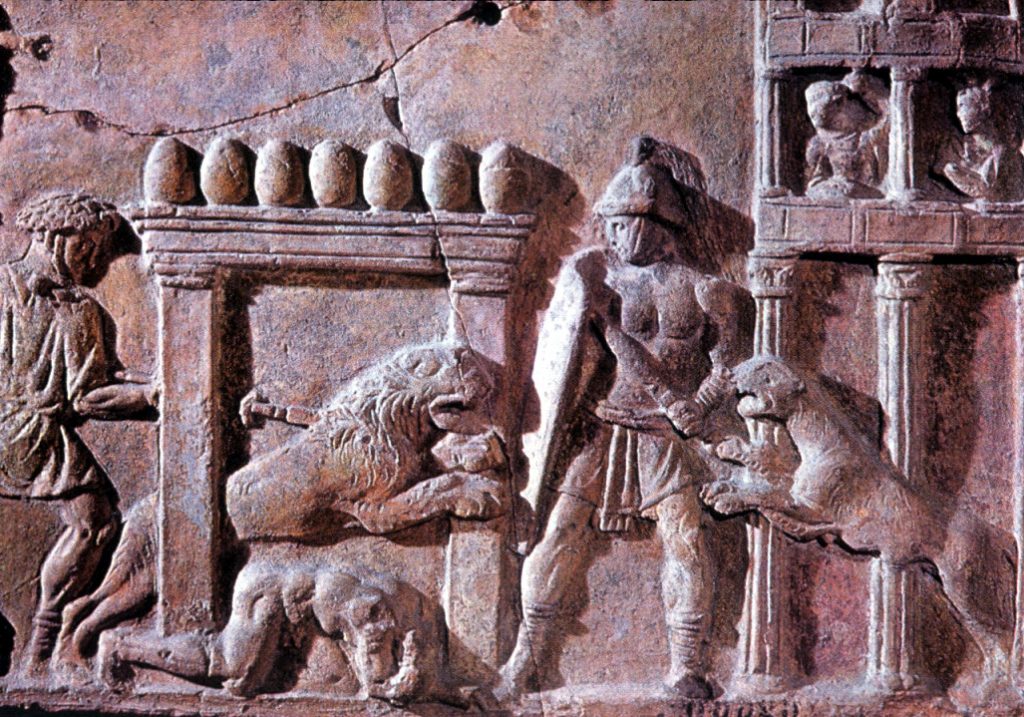

Alongside oral culture existed a semi-written world of short texts that blurred the boundary between private communication and public accusation. Libelli, brief written accusations or commentaries, circulated discreetly through elite and popular networks alike. Some were anonymous, others bore names that could be denied or disavowed if necessary. These texts were often read aloud in small gatherings, recopied by hand, or quietly passed from reader to reader, allowing ideas to travel without fixed authorship. Graffiti functioned as a crude but remarkably effective public medium, scrawled on walls in Pompeii, Rome, and provincial cities. These inscriptions mocked officials, recorded scandals, and commented on political events with a bluntness rarely found in formal literature. Their placement in public space gave them durability and visibility, transforming everyday walls into contested political surfaces where authority could be named, ridiculed, or challenged without permission.

Poetry and satire occupied a particularly potent position in this environment. Public recitations transformed literary performance into political theater. Audiences were not passive. They laughed, murmured, and remembered. Satirical verse allowed critique to masquerade as art, granting deniability while sharpening impact. The ambiguity of poetic language made it difficult to prosecute without admitting sensitivity. This ambiguity, however, also made satire threatening. It trained audiences to read between lines and to recognize power as fallible.

The Forum itself functioned as an information marketplace. Legal proceedings, senatorial announcements, triumphs, and punishments were public events designed to communicate authority. Yet these official messages competed constantly with unofficial interpretations. A verdict could be recast as injustice. A triumph could be mocked as excess. Power spoke loudly in Rome, but it was never the only voice. Public opinion emerged from friction between narrative and counter-narrative rather than from decree alone.

Roman authorities understood these dynamics with increasing clarity as the Republic gave way to empire. They did not fear falsehood in isolation, nor were they primarily concerned with factual accuracy. They feared circulation, repetition, and interpretive freedom. The danger lay not in any single comment, but in the cumulative effect of narratives that escaped official framing and accumulated authority through familiarity. This recognition explains why emperors targeted not only overt sedition, but also rumor-mongers, satirists, and informal commentators whose influence could not be neatly traced or disproven. In an environment where meaning was produced socially rather than administratively, suppression became a reactive strategy. Authority could punish speakers and destroy texts, but it could never fully command interpretation. The persistence of unofficial discourse ensured that power remained visible, contestable, and therefore anxious.

Augustus and the Legal Invention of “Public Order”

The rise of Augustus did not mark an abrupt abandonment of Roman law, but its careful repurposing through continuity rather than disruption. After decades of civil war, Romans were exhausted by instability and receptive to promises of peace, predictability, and moral restoration. Augustus positioned himself as the antithesis of chaos, presenting his authority as a necessary corrective rather than a personal seizure of power. He avoided the language of domination and instead emphasized tradition, renewal, and civic healing. His political genius lay in recognizing that repression would be more effective if it appeared as preservation. Rather than ruling openly through coercion, he embedded authority within legal forms that appeared conservative, familiar, and even reluctant. Public order became the central justification through which power was consolidated, allowing dissent to be reframed not as disagreement, but as a relapse into disorder that threatened collective survival.

Central to this transformation was the redefinition of maiestas, originally a concept tied to offenses against the Roman people and the state. Under Augustus, maiestas expanded to encompass actions and speech that could be construed as diminishing the dignity of the emperor or destabilizing the moral fabric of society. This elasticity proved crucial. Speech need not advocate rebellion to become criminal. Satire, rumor, and commentary could now be prosecuted if they were interpreted as corrosive to respect, harmony, or loyalty. The law did not silence speech directly. It surrounded it with risk, ambiguity, and consequence.

Augustus also advanced an extensive program of moral legislation that further blurred the boundary between private conduct and public security. Laws regulating marriage, adultery, and social behavior were framed as efforts to restore traditional Roman virtue. Yet these measures carried political weight. By casting morality as a matter of state interest, Augustus positioned himself as guardian not only of peace, but of values. Criticism of the regime could be interpreted as moral deviance or social contamination. Dissent was no longer merely political. It became unethical, antisocial, and dangerous to communal stability.

Exile emerged as a particularly effective tool within this legal framework precisely because it avoided the appearance of tyranny. Unlike execution, exile removed troublesome figures without creating martyrs or provoking public sympathy. It allowed the state to present itself as measured and restrained while still achieving silence. Writers, poets, and commentators who crossed ill-defined boundaries could be displaced under legal pretexts that avoided explicit acknowledgment of censorship. Exile also carried a psychological dimension. It severed individuals from networks of influence, memory, and audience, erasing them from the civic conversation without the drama of bloodshed. The punishment was severe enough to deter others, yet sufficiently ambiguous to preserve the fiction of lawful governance. Silence was produced not through spectacle, but through uncertainty and fear of invisibility.

The Augustan settlement demonstrates how authoritarian control can be established without abandoning legalism or openly suspending norms. By redefining public order as a fragile condition perpetually threatened by speech, Augustus normalized intervention into the realm of expression while maintaining the language of protection and stability. Law became the means through which power disciplined narrative rather than merely behavior, shaping not only what could be done, but what could safely be said or implied. This model proved durable. Later emperors would inherit not only institutions, but a conceptual framework in which repression appeared as prudence and censorship masqueraded as responsibility. Augustus did not invent suppression outright. He refined it, legalized it, and rendered it compatible with claims of peace.

Satirists as Targets: Ovid, Juvenal, and the Limits of Wit

Satire occupied an unstable and increasingly precarious position in Roman political culture because it thrived on ambiguity rather than confrontation. It was neither formal opposition nor private dissent, but a public mode of commentary that relied on suggestion, exaggeration, irony, and shared cultural recognition. Satirists did not accuse directly. They invited audiences to participate in meaning-making, to recognize targets without naming them, and to laugh in ways that quietly undermined authority. This indirectness made satire culturally potent and socially infectious, but it also rendered it politically dangerous. Because satire circulated affect as much as argument, it resisted easy containment. As imperial power consolidated and became more sensitive to challenges of legitimacy, this ambiguity grew intolerable. The very qualities that made satire effective as social critique made it threatening to a regime invested in narrative discipline and moral seriousness.

The exile of Ovid illustrates with particular clarity the vulnerability of wit under authoritarian legalism. Officially punished for a carmen et error, a poem and a mistake, Ovid’s offense was never clearly articulated, and that vagueness was itself revealing. His Ars Amatoria conflicted with Augustan moral legislation, but the problem was not simply erotic content. The poem’s tone was irreverent, playful, and socially subversive, treating morality as a game rather than a civic duty. Ovid did not attack Augustus, the imperial family, or the state directly. Instead, he destabilized the cultural seriousness upon which the regime’s moral authority depended. His exile demonstrates how censorship need not specify crimes when power is anxious about interpretation. Ambiguity itself becomes actionable when the state no longer trusts the audience to read “correctly.”

Ovid’s later poetry from exile reveals the psychological consequences of such repression. In the Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto, wit gives way to pleading, irony to despair. The transformation is instructive. Satire depends on an audience and a shared cultural space. Exile destroys both. By removing the satirist from circulation, the state did more than silence a voice. It severed the social conditions that made satire possible. The punishment extended beyond the individual to the genre itself.

Juvenal represents a later stage in this evolution, when satire survives but hardens. His work is bitter, accusatory, and often openly hostile. Where Ovid played, Juvenal condemns. This shift reflects a narrowing of expressive space. As legal and social risks increased, satire became less playful and more corrosive. Humor gave way to rage. The limits of wit had been discovered. What remained was denunciation delivered under the protection of exaggeration, moral absolutism, and temporal distance.

Ovid and Juvenal demonstrate that satire does not disappear under authoritarian pressure, but neither does it remain unchanged. It adapts defensively, altering tone, strategy, and audience relationship in response to risk. Yet adaptation comes at a cost. When regimes punish ambiguity, satire loses subtlety and gains aggression. Laughter becomes sharp-edged, and critique becomes polarized. The state may silence individual satirists, but it cannot erase the impulse to comment on power. What it can do is deform the cultural register of dissent itself, transforming shared humor into bitterness and communal irony into moral fracture. In this sense, repression does not eliminate critique. It reshapes it into a harsher, less generative form, leaving behind a public discourse that is angrier, narrower, and less capable of sustaining democratic imagination.

From Law to Terror: Speech Repression under Later Emperors

The legal architecture constructed under Augustus did not remain static, nor was it neutral in its later application. What began as a calibrated system of ambiguity and restraint gradually intensified as subsequent emperors inherited both the tools of control and the anxieties that accompanied concentrated power. The Julio-Claudian dynasty reveals how speech repression can evolve incrementally, almost imperceptibly, from legal management into something far more corrosive. Once the principle was established that dissenting expression posed a threat to public order and imperial dignity, later rulers faced constant pressure to demonstrate vigilance. Restraint itself could be read as weakness. The result was not merely continuity, but escalation. Law ceased to function primarily as a stabilizing framework and increasingly became a conduit for fear, signaling that authority would tolerate no ambiguity about loyalty or reverence.

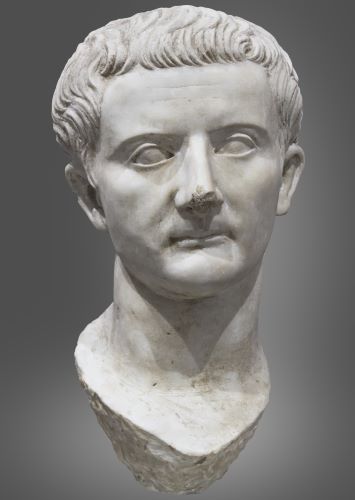

Under Tiberius, the law of maiestas expanded dramatically in both scope and frequency of application, setting a precedent that would haunt later reigns. Treason trials multiplied, often hinging on words spoken in private settings, fragmentary quotations, or interpretations of literary and historical expression. Jokes shared at dinners, ambiguous remarks overheard by servants, and even the praise of long-dead Republican figures could be construed as insults to imperial dignity. Crucially, enforcement depended less on direct imperial instruction than on the cultivation of a culture of denunciation. Informers, or delatores, emerged as indispensable agents of repression, rewarded materially and socially for their vigilance. In this way, speech repression became self-perpetuating. The state no longer needed to search actively for dissent. It embedded suspicion into social relations and encouraged citizens to police one another in pursuit of favor and survival.

This shift marked a profound change in the social experience of expression. Fear no longer stemmed solely from punishment, but from unpredictability. Because charges were interpretive rather than concrete, no clear boundary existed between permissible speech and criminal offense. Silence became the safest posture. Writers learned to self-censor not because laws were explicit, but because enforcement was arbitrary. In this environment, repression achieved its most effective form. Speech was constrained not by visible coercion, but by internalized caution.

The reigns of Caligula and Nero further illustrate how repression accelerates once legal restraint erodes into personal insecurity. Under these emperors, speech repression increasingly reflected temperament rather than policy. Mockery, satire, and even historical allusion could provoke violent response. Intellectuals and elites learned that reputation alone could invite suspicion. The boundary between political dissent and personal offense collapsed. When rulers interpret criticism as existential threat, law loses its stabilizing function and becomes a vehicle for vengeance.

By the time of Domitian, terror had become an organizing principle rather than an episodic excess. Tacitus describes an atmosphere in which writers destroyed their own works and audiences feared even attentive listening. The state’s objective was no longer simply to punish dissenters, but to erase the conditions under which dissent could be remembered. Memory itself became dangerous. Speech repression extended backward as well as forward, targeting historical interpretation and collective recall. The chilling effect was total, reaching beyond active criticism into the realm of thought and record.

The trajectory from Augustus to Domitian demonstrates how repression evolves when unchecked by institutional limits or cultural resistance. What begins as legal containment of expression, justified in the name of stability and order, can harden into systemic terror once rulers conflate authority with personal invulnerability. Roman history shows that speech repression does not remain proportionate or self-limiting. Each expansion creates new incentives for overreach, new categories of suspicion, and new reasons for fear. The danger lies not in any single law or emperor, but in the precedent that speech exists at the pleasure of power. When that premise becomes normalized, terror follows not as an accident or excess, but as a logical outcome of governance that treats interpretation itself as a crime.

Why Satire Is Always Dangerous to Power

Satire is dangerous to power not because it lies, but because it reveals, and it does so in ways that bypass formal debate. Unlike direct accusation or polemic, satire operates through recognition rather than proof. It assumes a shared cultural vocabulary between speaker and audience and invites participation rather than obedience. By exaggerating, inverting, or ridiculing authority, satire exposes the gap between official narratives and lived experience. Power depends on that gap remaining unseen or at least uninterrogated. When satire succeeds, it collapses the distance between what authority claims to be and how it is actually experienced. This collapse is destabilizing precisely because it feels obvious once noticed. Laughter marks the moment when authority loses its aura of inevitability. For this reason, regimes that tolerate criticism in principle often still fear humor in practice. Laughter signals not just dissent, but detachment. It announces that reverence has failed, and without reverence, coercion must work harder.

Satire also resists control because it is structurally elusive. It thrives on ambiguity, irony, and double meaning, making it difficult to prosecute without revealing insecurity. To punish satire, power must first acknowledge that it has been understood, and that acknowledgment alone confirms vulnerability. This paradox explains why authoritarian systems oscillate between toleration and repression. When satire is ignored, it spreads. When it is punished, it gains validation. The act of repression amplifies the very critique it seeks to suppress, transforming cultural commentary into political evidence of fragility.

More importantly, satire teaches audiences how to interpret authority over time. It does not merely criticize specific leaders, policies, or events. It reshapes habits of perception. By repeatedly framing power as absurd, hypocritical, or morally hollow, satire trains audiences to notice contradiction, excess, and pretense. This pedagogical function is what makes satire uniquely threatening. Violence can be condemned and forgotten. Scandal can be normalized. Ridicule lingers. It embeds itself in memory, language, and reflex, resurfacing whenever power repeats familiar patterns. Satire operates below the threshold of formal politics, altering how legitimacy itself is evaluated. It teaches people not what to think, but how to see. Once that lesson is learned, it cannot easily be unlearned.

Authoritarian regimes understand this intuitively, even when they cannot articulate it theoretically. Their hostility toward satirists is rarely proportional to the content of the satire itself. It is proportional to its effect. Satire undermines the emotional foundations of obedience by making reverence impossible. A ruler who can no longer be taken seriously has already lost something essential, even if institutions remain intact. This is why repression of satire so often precedes broader crackdowns on speech. When power cannot tolerate laughter, it has already begun to fear its own image.

Bridging Rome to the Modern World: Criminalizing Commentary as Continuity

The value of the Roman case lies not in direct equivalence, but in structural recognition across time. Rome did not arrest journalists, yet it repeatedly punished those who shaped public understanding through commentary, satire, and informal political narration. The mechanisms differed, but the governing logic endures. When power defines legitimacy as fragile, it treats interpretation itself as a threat that must be managed. The criminalization of commentary emerges not as an exceptional response to crisis, but as a routine defensive reflex. Roman authorities justified repression by invoking order, stability, and moral health, presenting intervention as preservation rather than control. Modern systems often employ the language of national security, public safety, institutional trust, or information integrity. The vocabulary shifts with context, but the underlying structure remains consistent: dissenting interpretation is recast as a danger to collective well-being rather than a feature of civic life.

Across historical settings, the suppression of commentary follows a recognizable and repeatable pattern. First, dissenting speech is reframed as irresponsibility rather than disagreement. Critics are accused not of being wrong, but of being reckless, divisive, or destabilizing. Second, legal mechanisms are expanded, reinterpreted, or selectively enforced to capture speech that once fell within tolerated bounds. Laws need not change dramatically; their application does. Finally, enforcement becomes exemplary rather than universal. The objective is not total silence, but deterrence through visibility. A small number of cases communicate risk to a much larger population. Rome refined this sequence over generations, demonstrating how law can discipline speech without openly abolishing it, and how repression can coexist with claims of legality and restraint.

Modern press suppression often mirrors this logic while preserving democratic aesthetics and institutional language. Arrests, surveillance, legal harassment, and regulatory pressure are framed as neutral enforcement or procedural necessity rather than political retaliation. Repression rarely announces itself as censorship. It presents itself as accountability, professionalism, or public protection. The danger lies in this normalization. When commentary is treated as a form of instability, journalists and critics are repositioned as risks rather than civic actors. Speech narrows not because it is formally banned, but because participation becomes costly, uncertain, and exhausting.

Rome’s experience offers a cautionary lesson about institutional drift. Once the state claims authority over interpretation, it rarely relinquishes it voluntarily. Each invocation of order justifies the next expansion of control. What begins as protection hardens into discipline. The Roman Empire shows that the erosion of expressive freedom does not require the collapse of law. It requires only the steady redefinition of commentary as threat. When criticism is criminalized in principle, even selectively, the boundary between governance and domination begins to blur. The continuity across time is not ideological. It is procedural, and durable.

Conclusion: When Power Cannot Laugh

The Roman experience demonstrates that the repression of speech rarely begins with overt brutality. It begins with anxiety. Power becomes brittle when it senses that its authority depends too heavily on performance, narrative, and emotional compliance. Satire exposes this brittleness by puncturing the seriousness upon which domination relies. The Roman emperors did not fear jokes as such. They feared what jokes revealed: that authority could be seen as contingent, excessive, or absurd. Once that perception takes hold, obedience becomes unstable. Laughter marks the moment when power is no longer experienced as inevitable.

Rome’s history shows that censorship is most effective when it is disguised as protection. Augustus did not silence critics by abolishing law, but by redefining it. Later emperors intensified this logic, transforming legal ambiguity into terror and social suspicion into enforcement. At no point did repression require the abandonment of legality. On the contrary, law was its principal instrument. This is the enduring lesson of Roman speech control. Authoritarian systems do not need to reject institutions. They need only to bend them toward the management of interpretation. When commentary is framed as disorder, silence appears responsible.

Satire matters in this context not because it topples regimes, but because it alters the emotional economy of power. It teaches audiences how to see rulers rather than what to think about them. Once authority becomes laughable, reverence collapses, and coercion must compensate for what legitimacy can no longer provide. Roman emperors understood this instinctively. Their hostility toward satirists was not personal thin-skinnedness, but strategic recognition. A ruler who cannot tolerate laughter has already conceded that force alone must sustain obedience.

The suppression of satire is not a side issue. It is a warning sign. When power cannot laugh, it signals fear of exposure rather than confidence in legitimacy. Rome reminds us that the criminalization of commentary does not announce tyranny in dramatic terms. It advances quietly, through legal justification, moral rhetoric, and selective punishment. The lesson is not that history repeats itself mechanically, but that structures endure. When authority begins to fear words more than violence, the conditions for domination are already in place.

Bibliography

- Ando, Clifford. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1951.

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Translated by Hélène Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1965.

- Beard, Mary. SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. New York: Liveright, 2015.

- Flower, Harriet I. The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace and Oblivion in Roman Political Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books, 1977.

- Edwards, Catharine. The Politics of Immorality in Ancient Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Galinsky, Karl. Augustan Culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Grant, Michael. “The Augustan ‘Constitution’.” Greece & Rome XVIII:54 (1949): 97-112.

- Habermas, Jürgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Translated by Thomas Burger. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1962.

- Jackob, Nikolaus. “Cicero and the Opinion of the People: The Nature, Role and Power of Public Opinion in the Late Roman Republic.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 17:3 (2007): 293-311.

- Juvenal. The Satires. Translated by Niall Rudd. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Laurence, Ray. Roman Passions: A History of Pleasure in Imperial Rome. London: Continuum, 2009.

- Millar, Fergus. The Emperor in the Roman World (31 BC–AD 337). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977.

- Ovid. Ars Armatoria. Translated by Henry T. Riley. London: George Bell and Sons,1885.

- —-. Epistulae ex Ponto. Translated by A. L. Wheeler. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1924.

- —-. Tristia. Translated by Peter Green. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

- Roller, Matthew. Constructing Autocracy: Aristocrats and Emperors in Julio-Claudian Rome. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Rosillo-López, Cristina (ed.). Communicating Public Opinion in the Roman Republic. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2019.

- Schudson, Michael. Why Democracies Need an Unlovable Press. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2008.

- Scott, James C. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990.

- Sloterdijk, Peter. Critique of Cynical Reason. Translated by Michael Eldred. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983.

- Snyder, Timothy. On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century. New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2017.

- Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars. Translated by Robert Graves. Revised by Michael Grant. London: Penguin Classics, 2007.

- Syme, Ronald. The Roman Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939.

- Tacitus. Agricola. Translated by H. Mattingly. Revised by S. A. Handford. London: Penguin Classics, 2009.

- —-. Annals. Translated by A. J. Woodman. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2004.

- Thompson, John B. Political Scandal: Power and Visibility in the Media Age. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000.

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. Rome’s Cultural Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Williams, Gordon. Satire and Society in Ancient Rome. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1989.

- Wiseman, T. P. Roman Drama and Roman History. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1998.

- Woodman, A. J. Tacitus Reviewed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Zanker, Paul. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1988.

- Zelizer, Barbie. About to Die: How News Images Move the Public. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.02.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.