The middle class saw itself as both the moral guardian and the practical engine of progress, defining what it meant to be civilized in an age of machines and empire.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Industry, Class, and the Reordering of British Society

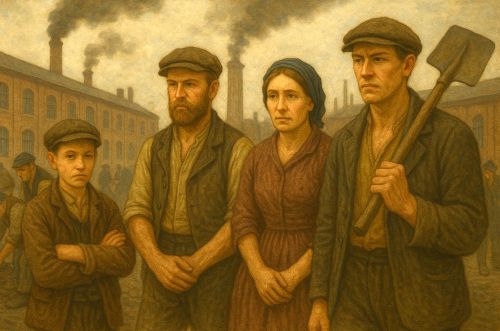

The nineteenth century marked one of the most profound social transformations in British history. The Industrial Revolution, which began in the late eighteenth century and accelerated through Queen Victoria’s reign, restructured not only the economy but the very fabric of social life. Factories, railways, and global trade networks reshaped landscapes and livelihoods, producing unprecedented wealth and urban expansion. Out of this upheaval emerged a new social group, the Victorian middle class, whose influence would come to define the age. Unlike the hereditary aristocracy that had long dominated Britain’s political and cultural order, this class drew its power from commerce, industry, and the professions. Its rise represented a shift from a society rooted in landed tradition to one governed by economic productivity and moral self-discipline.

The emergence of this middle class was not a smooth or uniform process. It was marked by tension between traditional hierarchies and the disruptive forces of industrial capitalism. Merchants, factory owners, bankers, lawyers, and shopkeepers formed the nucleus of a new social world that valued enterprise over inheritance and merit over birth. Census data from the early and mid-nineteenth century show the diversification of occupations in urban centers like Manchester, Birmingham, and Leeds, reflecting both the opportunities and inequalities of industrial society. The middle class stood between two poles, an aristocracy that still owned vast estates and a growing working class whose labor powered industrial expansion, and it sought to distinguish itself through both wealth and virtue.

The transformation of this social order extended far beyond economics. The Victorian middle class came to define the moral, political, and cultural ethos of modern Britain. Its values of respectability, thrift, and self-reliance shaped public institutions, family life, and the nation’s imperial self-image. What began as a response to industrial opportunity evolved into a new form of authority that reimagined what it meant to be British. What follows examines the rise of the Victorian middle class through its economic foundations, urban environments, moral codes, political ambitions, gender ideals, and transatlantic influence, tracing how industrial capitalism forged not only new fortunes but a new moral order that would outlive the century itself.

Economic Foundations: Industry, Enterprise, and Wealth Creation

The foundation of the Victorian middle class lay in the transformation of production and exchange brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Between 1820 and 1870, Britain became the world’s first industrial power, its factories supplying textiles, iron, and manufactured goods to a global market. The expanding economy produced opportunities for those who possessed the capital, skill, or education to navigate its new systems. Unlike the aristocracy, whose wealth derived from land, the middle class prospered through industrial ownership, mercantile enterprise, and the liberal professions. Their success was not inherited but achieved, reflecting a belief that diligence and prudence were the engines of advancement. Census records from the mid-nineteenth century show steady growth in commercial and professional occupations, confirming that the middle strata were no longer marginal but central to national prosperity.1

Factories, banks, and trading houses became symbols of middle-class ambition. Cotton magnates in Manchester, shipbuilders on the Clyde, and financiers in London reaped profits from mechanized industry and expanding colonial markets. Yet, the rewards of capitalism were accompanied by risk and volatility. Industrial slumps, bank failures, and competition from abroad revealed how precarious these new fortunes could be. This insecurity only strengthened the middle class’s attachment to thrift, self-help, and moral restraint, values they saw as safeguards against decline. Investment in railways and insurance reflected both a drive for innovation and a fear of uncertainty, blending enterprise with caution in a distinctly Victorian pattern of respectability.

Still, the rise of this class occurred within the shadow of aristocratic dominance. Landed elites retained control of Parliament and much of the political structure, and old wealth continued to confer social prestige even as new money multiplied. Industrialists and professionals often sought legitimacy by imitating the manners of the gentry, purchasing estates or marrying into noble families. The middle class therefore occupied an ambiguous position: both challengers to traditional privilege and aspirants to its cultural authority. The negotiation between economic power and social recognition would define their identity throughout the century.

Urbanization and the Geography of Class

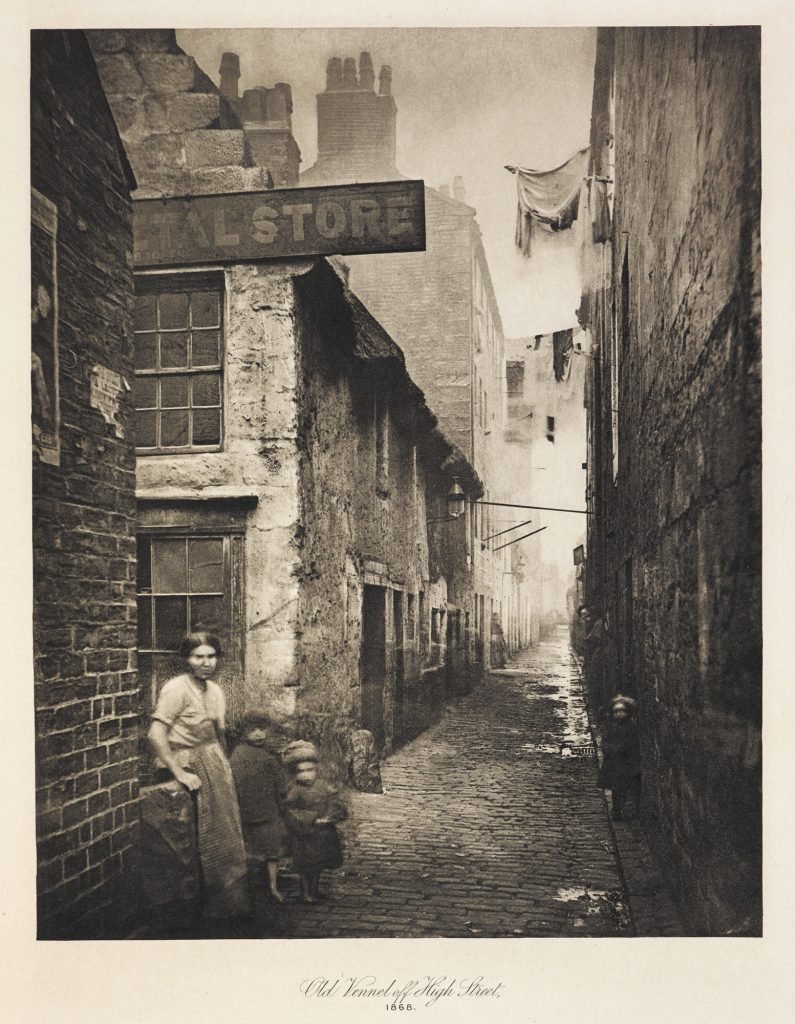

The rise of the Victorian middle class was inseparable from the transformation of Britain’s urban landscape. Industrialization concentrated labor, commerce, and capital in rapidly expanding cities, creating new spaces of opportunity and anxiety. Manchester, Birmingham, and Leeds grew from provincial towns into industrial metropolises whose economic dynamism contrasted sharply with their environmental squalor. The middle class, anxious to distance itself from the perceived disorder of industrial laborers, carved out distinct residential and commercial zones that expressed its social aspirations. Suburbs such as Edgbaston in Birmingham and Didsbury near Manchester embodied ideals of privacy, domestic comfort, and civic virtue, physical manifestations of a class seeking stability amid industrial turbulence.2

Urban planning reflected moral geography as much as economic necessity. The proliferation of terraced housing, clean water systems, and paved streets signaled not only rising affluence but also a determination to impose order on the chaos of urban growth.3 Municipal authorities, often led by middle-class reformers, invested in infrastructure to combat disease and disorder, equating public health with civic virtue. Libraries, museums, and Mechanics’ Institutes followed, designed to elevate taste and cultivate disciplined intellect.4 In this landscape, cleanliness and respectability became markers of moral worth as well as social rank.

The middle class also transformed urban economies through their consumption habits. Department stores, tea rooms, and print shops catered to new expectations of comfort and refinement. Domestic interiors were filled with symbols of taste (pianos, carpets, and polished furniture) reinforcing the notion that material display could express moral character.5 Industrial capitalism thus gave rise to a consumer culture that blurred the line between necessity and aspiration. Wealth was to be enjoyed but also displayed within limits of propriety, reflecting the moral calculus of a class that equated success with virtue.

Yet, these new urban ideals were never neutral. The very cleanliness and order celebrated by the middle class often implied exclusion. Zoning, property qualifications, and social etiquette defined who belonged within respectable spaces. Working-class districts remained overcrowded and neglected, their inhabitants treated as moral subjects to be improved rather than citizens to be empowered.6 Reform campaigns sought to “civilize” the poor through education and temperance, but such efforts often reinforced class boundaries even as they claimed humanitarian intent. The Victorian city, for all its progress, remained a geography of inequality built upon moral distinction.

In the interplay between industrial expansion and social mobility, the middle class made the city both its stage and its fortress. It projected ideals of discipline and decency onto urban form while insulating itself from the instability of the world it had helped to create. By shaping the geography of class, the Victorian middle class not only secured its own identity but also laid the foundations for the modern urban order, one that still bears the imprint of its moral and material hierarchies.

Culture, Morality, and Respectability

If economic success secured the material foundations of the Victorian middle class, moral conduct defined its spiritual legitimacy. Respectability became the hallmark of class identity, embodying values that distinguished the “civilized” from the “vulgar.” Work, thrift, and temperance were elevated into moral duties, transforming economic behavior into a kind of civic religion. The home was its sanctuary, the family its congregation. Religious observance, particularly within Protestant denominations such as Methodism and Congregationalism, reinforced the ethic of personal discipline and social responsibility that gave the middle class its cohesion.7

This moral order extended beyond personal conduct into public reform. Middle-class activists championed education, poor relief, and prison reform as expressions of benevolence rooted in moral stewardship.8 Beneath their philanthropy, however, lay a belief that poverty was as much a moral failing as a social condition. By promoting literacy and sobriety among the working class, reformers sought to instill the virtues they believed had secured their own success. Sunday schools multiplied across Britain, instructing children in both reading and righteousness. The temperance movement flourished, equating abstinence with moral purity and civic virtue. In these campaigns, charity and control intertwined, reflecting both compassion and condescension.

Literature and print culture played a crucial role in shaping this moral landscape. The explosion of newspapers, serialized novels, and didactic essays provided a mirror through which the middle class could see itself and its values affirmed.9 Popular fiction celebrated industrious heroes and virtuous heroines who triumphed through perseverance rather than inheritance. Conduct manuals, widely circulated through lending libraries, instructed readers on everything from table manners to moral deportment.10 Respectability thus became a performative ideal: one learned, rehearsed, and displayed through both behavior and consumption.

The domestic sphere, central to Victorian morality, embodied the class’s vision of social order. Within the home, men and women occupied complementary but unequal roles that reflected a broader ideology of “separate spheres.” Men were to labor and lead in the public world; women were to nurture and moralize within the private one.11 Domestic comfort, religious devotion, and female modesty were presented as the moral foundations of civilization. The middle-class home was not merely a residence but a statement, a moral fortress separating virtue from vice, stability from chaos.

At the same time, the language of respectability concealed contradictions. The pursuit of moral purity coexisted with economic exploitation, and the public celebration of virtue masked anxieties about hypocrisy and decline. The working poor were often judged by standards they could not afford to meet, while the upper classes quietly transgressed the very codes they espoused.12 Middle-class moralism functioned as both a guide to conduct and a mechanism of control, reinforcing class boundaries under the guise of universal virtue.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the Victorian middle class had succeeded in turning its values into the moral grammar of the nation. Its emphasis on self-help, decency, and diligence infused the institutions of education, religion, and governance.13 Yet, beneath this triumph lay a deeper paradox: a society that equated morality with prosperity could never fully separate virtue from privilege. Respectability became both the justification for success and the language by which inequality was sanctified.

Politics and Reform: From Exclusion to Influence

Economic success and moral authority soon translated into political ambition. By the early nineteenth century, Britain’s electoral system still privileged landowners and aristocrats, excluding the industrial and professional classes who now powered the economy. The agitation for parliamentary reform became the political expression of middle-class self-confidence. The passage of the Reform Act of 1832 was a watershed moment, extending the vote to property-owning men in towns and redistributing parliamentary seats to reflect industrial growth.14 This legislation did not create democracy, but it marked the political coming-of-age of the middle class. Merchants, lawyers, and manufacturers began to enter Parliament, bringing with them a new rhetoric of efficiency, moral improvement, and free enterprise.

Middle-class reformers also transformed local governance. Municipal reform acts in the 1830s and 1840s gave towns greater autonomy, enabling civic elites to manage their own affairs.15 Town councils, often dominated by businessmen and professionals, invested in sanitation, public lighting, and education. The ethos of civic duty, the belief that good citizens should improve their communities, became a defining feature of middle-class political identity. In cities like Birmingham, Joseph Chamberlain’s brand of “municipal socialism” would later embody this spirit of pragmatic progressivism, linking moral purpose with public administration.

Politics for the Victorian middle class was as much about principle as about power. Free trade became a moral as well as economic doctrine, celebrated as the foundation of prosperity and peace.16 The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, driven by middle-class pressure, symbolized a triumph of industrial rationality over aristocratic privilege. Campaigns for religious toleration, civil service reform, and education expanded the scope of civic participation, reflecting the belief that progress required both moral and institutional refinement. At the same time, a persistent paternalism colored these reforms. Political inclusion was framed as a privilege earned through respectability, not a universal right.

Despite its growing influence, the middle class remained wary of the radicalism emerging from below. Chartist petitions for universal male suffrage were met with suspicion and sometimes repression, revealing the limits of middle-class liberalism.17 The rhetoric of self-help and meritocracy justified their own advancement while restraining demands for broader equality. Even when later reforms expanded the franchise in 1867 and 1884, many middle-class leaders sought to preserve distinctions between the “deserving” and “undeserving” citizen. The class that had once fought for inclusion now guarded its position against those it deemed unfit for political power.

By the century’s end, the middle class had woven itself into the fabric of British governance. Through local councils, reform movements, and Parliament itself, it infused politics with its characteristic blend of moralism, efficiency, and caution.18 Yet its ascendancy carried contradictions. The same ideals that inspired reform also justified exclusion. In claiming to represent national virtue, the Victorian middle class blurred the line between civic responsibility and self-interest, setting the stage for the political tensions that would define the modern democratic state.

Gender and the Middle-Class Home

No institution reflected the values of the Victorian middle class more fully than the home. Domestic life became the moral centerpiece of the age, a private world that symbolized public virtue. Middle-class homes were designed as sanctuaries from the competitive world of commerce and politics, embodying ideals of stability, cleanliness, and moral order. The separation of home and workplace, made possible by industrial prosperity, redefined gender roles and social expectations. Men became identified with the rational, productive sphere of labor, while women were assigned to the emotional, nurturing realm of domestic life. This doctrine of “separate spheres” was presented not as social convention but as natural law, sanctified by religion and reinforced through education and literature.19

The home thus became both a symbol of moral authority and a site of constraint. Women were idealized as “angels of the house,” charged with cultivating purity, piety, and emotional warmth. Their labor (managing servants, raising children, and preserving gentility) was invisible but indispensable to middle-class respectability.20 Female education emphasized refinement and domestic skill rather than intellectual or political ambition. Yet, even within these constraints, women found avenues for influence through charitable work, religious teaching, and social reform. Philanthropic organizations such as the Girls’ Friendly Society and the Young Women’s Christian Association reflected the feminization of moral authority that accompanied industrial modernity.21

At the same time, middle-class domestic ideals carried deep contradictions. The insistence on purity and dependency confined women to the margins of public life while holding them responsible for the nation’s moral health. The domestic ideal also ignored the realities of working women, whose labor underpinned the comfort of the middle class, from servants to textile workers.22 The household, celebrated as a refuge from exploitation, depended on the exploitation of others. Even within middle-class families, growing awareness of marital inequality inspired early feminist critique and reform movements seeking access to education, property rights, and suffrage.

By the late nineteenth century, the ideal of separate spheres began to erode under the pressures of urbanization, education, and social reform. Middle-class women entered universities, joined professional societies, and led campaigns for temperance and the vote. The home remained central to their moral vision, but its walls no longer confined them.23 In challenging the very boundaries that had defined their respectability, these women reshaped the moral language of the Victorian middle class itself, turning domestic virtue into a platform for public activism that would reverberate well into the twentieth century.

Across the Atlantic: The Victorian Ethos in America

While the Industrial Revolution remade British society, its moral and cultural influence extended far beyond the British Isles. In the United States, the same combination of industrial expansion, urban growth, and moral reform produced a parallel middle class whose ideals closely resembled those of Victorian Britain. By the mid-nineteenth century, cities like Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago teemed with merchants, professionals, and small manufacturers who saw themselves as the bearers of order in an age of rapid change.24 Although the United States lacked an entrenched aristocracy, Americans adopted many of the moral and domestic codes that defined the Victorian worldview. The ideal of the “self-made man,” rooted in individual enterprise and Christian virtue, became the republic’s secular creed.

Industrialization in America accelerated after 1830, creating vast fortunes and transforming labor relations much as it had in Britain. Railroads, textile mills, and steelworks gave rise to a new bourgeois elite whose prosperity rested on mechanized production and a disciplined labor force.25 The moral tension between wealth and virtue, however, remained constant. Business leaders invoked providence to justify success, portraying industry as a moral mission that advanced civilization. This moralization of capitalism underpinned the ethos of respectability that spread through churches, schools, and voluntary associations. The American middle class, like its British counterpart, found moral reassurance in productivity and discipline, the conviction that economic progress was inseparable from divine favor.

The domestic sphere served as the cornerstone of this transatlantic moral order. American homes were described as “citadels of virtue,” where women upheld moral purity and men exercised benevolent authority.26 Advice literature and domestic manuals, from Catharine Beecher’s Treatise on Domestic Economy to periodicals like Godey’s Lady’s Book, instructed families in cleanliness, moderation, and faith. Middle-class women, though confined by domestic ideology, found new outlets for influence in reform movements. The rise of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the abolitionist cause reflected the extension of feminine virtue into public life, blending piety with political activism.27 In this fusion of domesticity and reform, American women helped translate Victorian morality into a force for social change.

Religion remained a unifying thread. Protestant denominations (particularly Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian) reinforced the connection between faith, industry, and respectability. Sermons linked salvation to sobriety and diligence, while Sunday schools instilled moral discipline in children across class lines.28 The Second Great Awakening earlier in the century had already tied moral reform to national destiny, and by the Victorian era, this spirit merged seamlessly with industrial capitalism. Philanthropic and missionary societies flourished, their efforts often infused with a belief in the moral superiority of middle-class life. Moral virtue became a marker not only of piety but of citizenship itself.

Yet, as in Britain, the American version of Victorian morality masked deep contradictions. The cult of domestic virtue excluded enslaved people, immigrants, and the urban poor from the moral community it claimed to represent. The same middle class that championed temperance and education often defended racial segregation and opposed labor organization.29 Industrial capitalism produced new forms of inequality, while the rhetoric of self-reliance blamed the poor for their own condition. Respectability became a boundary, a way to define who was fit to participate in the moral and political life of the nation.

By the century’s close, the transatlantic Victorian ethos had become a shared moral language of modern capitalism.30 Both British and American middle classes defined themselves through work, restraint, and civic virtue, seeing in their success the evidence of moral superiority. Yet, their legacy was double-edged: they democratized aspiration while sanctifying inequality. Across the ocean, the same moral vocabulary that upheld reform also justified exclusion, revealing how the ideals of progress and propriety could serve both liberation and control.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Victorian Middle Class

By the final decades of the nineteenth century, the Victorian middle class had remade not only Britain but much of the industrialized world in its image. The class that began as a product of economic change ended as an architect of cultural hegemony. Its values (hard work, thrift, discipline, and moral restraint) became the unofficial creed of modern capitalist society.31 From boardrooms to schoolrooms, these ideals shaped expectations of citizenship and success. Industrial prosperity had produced a social order that equated wealth with virtue and respectability with righteousness. The middle class saw itself as both the moral guardian and the practical engine of progress, defining what it meant to be civilized in an age of machines and empire.

Yet the triumph of the middle class was shadowed by contradiction. Its institutions and reforms often deepened the inequalities they claimed to redress. Education and philanthropy provided opportunity for some while reinforcing the boundaries of class and gender for others.32 The language of meritocracy masked the persistence of privilege, while the domestic ideal continued to confine women even as it exalted them. Industrial capitalism created unprecedented prosperity, but also alienation, exploitation, and poverty on a scale that respectability alone could not conceal. For every mansion that rose in the suburbs, a slum persisted in the city center, both products of the same economic system.

The moral and political legacy of the Victorian middle class endured long after its material conditions changed. Its faith in progress, individual effort, and social order influenced twentieth-century liberalism, education, and welfare reform.33 At the same time, critics of industrial society, from socialists to modernists, defined their opposition by rejecting Victorian respectability and its moral certainties. The world the Victorians built was not easily undone; their ideals survived in the very structures that later generations sought to reform.

In retrospect, the rise of the Victorian middle class represents one of the most consequential social revolutions in modern history. It created a culture that merged capitalism with conscience, industry with morality, and self-interest with virtue.34 Its contradictions mirror those of modernity itself, a civilization both progressive and unequal, humane and hierarchical. The Victorian middle class did not merely inherit a changing world; it imagined and imposed its own order upon it, leaving a legacy that continues to shape the moral vocabulary of the modern age.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Great Britain Census of 1851: General Report (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1854), 37–44.

- Census of Great Britain, 1861: Population Tables, Vol. II (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1863), 112–117.

- Report of the General Board of Health on the State of Large Towns and Populous Districts (London: HMSO, 1845), 22–25.

- Mechanics’ Institutions: Report of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (London: SDUK, 1850), 9–14.

- Illustrated London News, December 24, 1859, 612.

- Report of the Health of Towns Commission (London: HMSO, 1844), 51–56.

- Religious Worship in Great Britain: Census Report of 1851 (London: HMSO, 1853), 18–22.

- The Report of the Commissioners for Inquiring into the Administration and Practical Operation of the Poor Laws (London: HMSO, 1834), 6–9.

- The Times (London), July 14, 1856, 3.

- The Book of Household Management (London: S.O. Beeton, 1861), Preface.

- The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, August 1862, 97–99.

- Morning Chronicle, “Labour and the Poor,” February 8, 1850, 2.

- Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge: Annual Report (London: SPCK, 1870), 11–13.

- Parliamentary Papers: Representation of the People Act, 1832 (London: HMSO, 1833), 5–9.

- Report from the Select Committee on Municipal Corporations (London: HMSO, 1835), 12–15.

- The Anti–Corn Law Circular (Manchester: Anti–Corn Law League, 1843), 3–4.

- Chartist Petitions and Reports, 1839–1848 (London: National Archives, HO 44/46), 28–32.

- Hansard Parliamentary Debates, 3rd ser., vol. 292 (London: HMSO, 1884), 137–141.

- The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, June 1860, 44–46.

- Coventry Patmore, The Angel in the House (London: John W. Parker, 1854), 7–9.

- Annual Report of the Young Women’s Christian Association of Great Britain, 1877, 4–6.

- Report of the Children’s Employment Commission (London: HMSO, 1863), 82–87.

- Women’s Suffrage Journal, July 1882, 121–123.

- U.S. Census of 1850: Manufactures (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1853), 12–15.

- Annual Report of the Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor, 1870, 27–29.

- Godey’s Lady’s Book, March 1854, 123–126.

- Annual Report of the National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, 1885, 3–6.

- American Sunday School Union: Annual Report, 1868, 10–14.

- Frederick Douglass’ Paper, October 21, 1853, 1.

- The Independent (New York), April 2, 1885, 4.

- Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes (London: HMSO, 1885), 4–7.

- Report of the Commissioners on Secondary Education (London: HMSO, 1895), 21–25.

- The Fabian Tracts, No. 70 (London: Fabian Society, 1896), 2–4.

- The Nineteenth Century: A Monthly Review, January 1899, 1–5.

Bibliography

- American Sunday School Union: Annual Report. Philadelphia: American Sunday School Union, 1868.

- Annual Report of the Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor. Boston: Wright & Potter, 1870.

- Annual Report of the National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. Chicago: Woman’s Temperance Publishing Association, 1885.

- Annual Report of the Young Women’s Christian Association of Great Britain. London: YWCA, 1877.

- Chartist Petitions and Reports, 1839–1848. London: National Archives, HO 44/46.

- Coventry Patmore, The Angel in the House. London: John W. Parker, 1854.

- Census of Great Britain, 1861: Population Tables, Vol. II. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1863.

- Frederick Douglass’ Paper. Rochester, NY, October 21, 1853.

- Godey’s Lady’s Book. Philadelphia, March 1854.

- Great Britain Census of 1851: General Report. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1854.

- Hansard Parliamentary Debates. 3rd series, vol. 292. London: HMSO, 1884.

- Illustrated London News. December 24, 1859.

- Mechanics’ Institutions: Report of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London: SDUK, 1850.

- Morning Chronicle. “Labour and the Poor.” February 8, 1850.

- Parliamentary Papers: Representation of the People Act, 1832. London: HMSO, 1833.

- Religious Worship in Great Britain: Census Report of 1851. London: HMSO, 1853.

- Report from the Select Committee on Municipal Corporations. London: HMSO, 1835.

- Report of the Children’s Employment Commission. London: HMSO, 1863.

- Report of the Commissioners on Secondary Education. London: HMSO, 1895.

- Report of the General Board of Health on the State of Large Towns and Populous Districts. London: HMSO, 1845.

- Report of the Health of Towns Commission. London: HMSO, 1844.

- Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes. London: HMSO, 1885.

- Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge: Annual Report. London: SPCK, 1870.

- The Anti–Corn Law Circular. Manchester: Anti–Corn Law League, 1843.

- The Book of Household Management. London: S.O. Beeton, 1861.

- The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine. London: Various issues, 1860–1862.

- The Fabian Tracts, No. 70. London: Fabian Society, 1896.

- The Independent. New York, April 2, 1885.

- The Nineteenth Century: A Monthly Review. London: January 1899.

- The Report of the Commissioners for Inquiring into the Administration and Practical Operation of the Poor Laws. London: HMSO, 1834.

- The Times. London, July 14, 1856.

- U.S. Census of 1850: Manufactures. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1853.

- Women’s Suffrage Journal. London: July 1882.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.29.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.