The Late Roman Republic demonstrates with unusual clarity that political popularity and political power are not synonymous.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Mass Appeal and Institutional Fragility

The collapse of the Late Roman Republic is often narrated as a drama of ambition, betrayal, and violence. Yet such accounts risk obscuring a more structural reality. Roman politics in the first century BCE did not fail because popular support disappeared, but because it proved insufficient. Mass enthusiasm, however intense, could not substitute for the complex web of elite cooperation and institutional legitimacy that sustained republican governance. The central paradox of the period lies in the persistence of popularity amid the erosion of power.

Roman political culture encouraged spectacle and rewarded personal loyalty, but it was never governed directly by crowds. Public assemblies, elections, and triumphs created visibility and momentum, yet real authority depended on elite alignment within the Senate, magistracies, and provincial command structures. The Republic functioned through negotiated consent among competing power holders. When that consent fractured, no amount of popular acclaim could stabilize the system. Charisma energized politics, but it could not anchor it.

This fragility became increasingly visible as individual figures accumulated unprecedented followings. Reformist language, appeals to grievance, and public generosity expanded personal constituencies, particularly among urban populations and veterans. These strategies were effective in mobilization but destabilizing in governance. As political competition intensified, loyalty to individuals began to replace loyalty to shared norms. The result was not immediate collapse, but progressive isolation, as undecided elites grew wary of aligning themselves with polarizing leaders.

The Late Republic thus reveals a critical distinction between popularity and power. Political survival did not hinge on maintaining a base, but on retaining the cooperation of those who controlled institutional levers and withheld commitment until outcomes became clear. When moderates and opportunists withdrew their consent, charismatic leaders found themselves surrounded by supporters yet unable to govern. The Roman experience demonstrates that mass appeal, absent institutional integration, accelerates fragility rather than preventing it.

The Roman Political System and the Limits of Popular Power

The Roman Republic was not designed to convert mass enthusiasm directly into sustained authority. While popular assemblies played a visible role in elections and legislation, their function was bounded by tradition, procedure, and elite mediation. Magistracies were annual, collegial, and embedded within a dense web of norms that privileged consensus among the ruling class. Popular support could elevate a politician temporarily, but it could not secure continuity without senatorial tolerance and elite cooperation.

Roman political power flowed through offices rather than offices flowing from the people. Consuls, praetors, and tribunes derived legitimacy from election, yet their effectiveness depended on networks of patronage, precedent, and reciprocal obligation. Informal constraints mattered as much as formal rules. A magistrate who alienated too many peers could find himself obstructed, isolated, or sidelined regardless of his popularity. The Republic operated less as a democracy of numbers than as a competitive oligarchy that required broad elite consent to function.

Public assemblies amplified voices but rarely resolved structural conflict. Voting procedures favored those with time, proximity, and resources, limiting participation even within ostensibly popular institutions. Moreover, assemblies could approve measures but could not enforce cooperation across offices or commands. Legislation passed without elite buy-in often proved difficult to implement, vulnerable to delay, reinterpretation, or outright resistance. Popular power was therefore episodic rather than systemic.

This system produced a recurring illusion of popular sovereignty. Spectacle created the appearance of decisive mass control, particularly during moments of crisis or reform. Triumphs, games, distributions, and speeches generated loyalty and visibility, reinforcing the idea that the crowd could make or break leaders. Yet these moments rarely translated into durable authority. Once the spectacle ended, politics returned to negotiation among those who controlled armies, provinces, and administrative continuity.

The limits of popular power became most apparent when politics polarized. As competition sharpened, elites became less willing to compromise with figures who mobilized crowds against them. Popularity then became a liability rather than an asset, signaling unpredictability and threat. The Roman political system tolerated ambition, but it resisted domination. When mass appeal ceased to reassure elites and instead alarmed them, institutional fragility deepened. The Republic’s failure was not that it ignored the crowd, but that it could not reconcile popular mobilization with elite governance.

Julius Caesar: Charisma, Reform, and Elite Alienation

Julius Caesar’s rise illustrates how charisma can accelerate political success while simultaneously narrowing the coalition required to sustain it. His appeal was genuine and broad, rooted in military achievement, public generosity, and a reformist posture that framed him as a champion of the marginalized. Veterans, urban populations, and indebted citizens responded to a leader who appeared to deliver tangible benefits rather than procedural caution. Yet this popularity masked a steady contraction of elite trust, a development that would prove decisive.

Caesar’s reforms were not merely tactical but performative. Debt relief measures, land distributions, and public works signaled responsiveness to grievance and hardship. These initiatives built loyalty by translating rhetoric into action, reinforcing the sense that Caesar governed for those excluded from senatorial privilege. At the same time, the speed and unilateral character of these measures unsettled peers who understood reform as a negotiated process rather than a personal mandate. What energized the crowd alarmed the Senate.

Military success deepened this divide. Caesar’s conquests in Gaul generated unprecedented personal loyalty among troops and immense prestige at Rome. Triumphs, spoils, and narratives of victory elevated him beyond conventional magistrates. Yet the very scale of this success destabilized republican norms. Commanders were expected to serve the state, not overshadow it. As Caesar’s stature grew, so too did the perception that his ambitions exceeded institutional bounds, regardless of his professed loyalty to the Republic.

Elite alienation did not emerge overnight. It accumulated through repeated confrontations, bypassed conventions, and perceived slights. Caesar’s willingness to override senatorial opposition reinforced the belief that compromise was no longer possible. Moderates who might have tolerated reform grew uneasy with concentration of authority, while opponents hardened into existential resistance. Polarization intensified not because Caesar rejected cooperation outright, but because his methods made cooperation increasingly costly for others.

The crossing of the Rubicon symbolized this breakdown, but it did not create it. By the time civil war erupted, Caesar’s coalition was already asymmetrical. He commanded devotion from soldiers and popular acclaim from many citizens, yet he faced a Senate fractured between fear and hostility. The Republic’s mechanisms for reconciliation had eroded. Conflict became the means by which unresolved tensions were finally addressed, albeit destructively.

Caesar’s assassination revealed the limits of his political architecture. His death did not dissolve popular loyalty, but it exposed the absence of a shared institutional framework capable of absorbing his dominance. Supporters mourned, crowds protested, and memory was mobilized, yet governance stalled. Charisma had carried Caesar far, but it could not bridge the widening gulf between mass enthusiasm and elite consent. His career demonstrates how popularity can accelerate ascent while hastening isolation.

Popularity without Governability after Caesar’s Death

The assassination of Julius Caesar exposed the fragility of a political order sustained by personal authority rather than institutional reconciliation. In the immediate aftermath, popular sympathy surged. Crowds gathered, veterans rallied, and public mourning underscored the depth of Caesar’s personal appeal. Yet this outpouring did not resolve the central problem of Roman politics. The Republic remained structurally paralyzed, lacking a mechanism to translate mass emotion into stable governance.

Caesar’s funeral dramatized this contradiction. Mark Antony’s oration mobilized grief and anger, transforming public sentiment into a volatile force. Statues were attacked, conspirators fled, and the city teetered on unrest. Yet spectacle could not substitute for settlement. No coherent political program emerged that could reconcile Caesar’s supporters with senatorial authority. The crowd could protest and intimidate, but it could not legislate consensus or rebuild trust among elites.

The Senate’s response revealed the depth of institutional breakdown. Attempts to restore normalcy through amnesty and compromise satisfied no one. Caesar’s supporters viewed reconciliation as betrayal, while his opponents feared retaliation. Each faction claimed legitimacy, but none possessed the authority to impose resolution without provoking further conflict. Popular sympathy for Caesar thus became politically inert, powerful in symbolism but weak in execution.

This period highlights the limits of posthumous charisma. Caesar’s name remained potent, invoked by rivals seeking legitimacy, yet it offered no guidance for governance. Competing actors appropriated his legacy while undermining one another. Without the unifying presence of the leader himself, loyalty fragmented into competing interpretations, each incapable of commanding broad institutional allegiance.

Popularity without governability proved unsustainable. The Republic drifted not because the masses rejected Caesar’s vision, but because no coalition could convert that vision into workable authority. The aftermath of the Ides of March demonstrates a recurring dynamic in political systems built around strong personalities: once the individual is removed, what remains is intensity without coordination, devotion without direction.

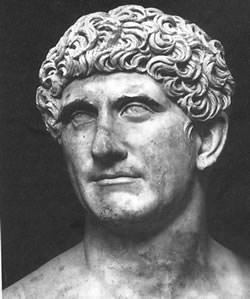

Marcus Antonius and the Persistence of the Crowd

Marcus Antonius inherited much of Caesar’s popular support, but none of the institutional equilibrium that might have made it effective. His early positioning as Caesar’s avenger and legitimate heir resonated with urban crowds and veterans who viewed the assassination as an act of elite treachery. Public ceremonies, rhetorical appeals, and the careful cultivation of memory sustained this loyalty. Antony remained a figure of mass appeal even as political order continued to disintegrate.

Yet Antony’s reliance on spectacle and personal allegiance intensified elite distrust. His conduct as consul and later as a power broker appeared erratic, transactional, and dismissive of republican norms. While these traits reinforced his authenticity among supporters who distrusted the Senate, they alarmed undecided elites seeking predictability. For many within Rome’s governing class, Antony represented continuity of chaos rather than restoration of stability.

The persistence of the crowd masked the erosion of strategic position. Antony’s popular backing created the illusion of strength, but it failed to secure decisive institutional advantages. Alliances frayed, rivals consolidated power elsewhere, and administrative control slipped from his grasp. Popular loyalty proved incapable of compensating for the loss of elite cooperation, particularly as competition intensified and alternatives emerged.

Antony’s career illustrates the durability and limits of charisma. He retained crowds even as his capacity to govern narrowed. What ultimately constrained him was not the collapse of enthusiasm, but the withdrawal of those who controlled resources, legitimacy, and continuity. The crowd persisted, but the Republic moved on. Popularity endured, yet power relocated.

The Role of Swing Elites and Political Opportunists

The decisive actors in the final decades of the Roman Republic were neither the most ideologically committed nor the most visibly mobilized. They were the undecided elites, provincial governors, equestrians, and political opportunists who delayed commitment until outcomes clarified. These figures did not require moral conviction to act. They required assurance. Their loyalty was contingent, shaped less by charisma than by calculations of stability, security, and future advantage.

Such actors operated within a political culture that rewarded flexibility. Roman elites were accustomed to shifting alliances, pragmatic accommodation, and strategic silence. In periods of uncertainty, withholding support was often the safest course. As competition intensified between rival strongmen, fence-sitters observed rather than intervened. When charismatic leaders failed to consolidate broad institutional cooperation, hesitation hardened into defection. What appeared externally as betrayal was, internally, risk management.

This dynamic proved fatal for figures like Antony. As long as outcomes remained uncertain, swing elites resisted alignment. Once alternatives appeared more viable, particularly those offering administrative continuity and restraint, allegiance shifted rapidly. These defections were not ideological repudiations of popular politics. They were judgments about governability. Crowds could cheer, but elites controlled legions, finances, and provincial administration. Their movement determined the Republic’s trajectory.

The collapse of the Republic thus hinged on the withdrawal of the middle rather than the mobilization of extremes. Political opportunists did not need to oppose charismatic leaders openly. They simply aligned elsewhere. Rome’s transformation demonstrates that institutional power consolidates where uncertainty diminishes. Strongmen retained followers, but they lost the audience that mattered most. The Republic ended not with a rejection of popularity, but with the decisive silence of those who chose stability over spectacle.

When Charisma Becomes a Liability

Charisma is often treated as an unqualified political asset, yet in institutional systems it carries inherent risks. In the Late Roman Republic, personal magnetism accelerated mobilization but narrowed the space for cooperation. Charismatic leaders drew loyalty inward, concentrating allegiance around themselves rather than distributing it across shared norms. What initially unified supporters gradually alienated those whose participation depended on predictability and reciprocity rather than emotional commitment.

As charisma intensified, it altered elite incentives. Cooperation with a dominant figure increasingly appeared as submission rather than partnership. Senators and magistrates who might have accepted reform resisted personal subordination. Even sympathetic elites hesitated to align themselves too closely with leaders whose authority rested on spectacle and personal loyalty rather than negotiated consensus. Charisma thus transformed political disagreement into existential threat, hardening opposition and discouraging compromise.

This effect was compounded by the visibility of personal rule. Charismatic leaders were constantly performing, constantly signaling dominance, and constantly reaffirming loyalty. Such performance left little room for shared credit or collective ownership of outcomes. Failures became personal, successes exclusive. For undecided elites, alignment carried escalating reputational risk. Supporting a strongman meant tying one’s fate to an individual rather than to institutions that could absorb loss and change.

Over time, charisma also distorted decision-making. Leaders surrounded by loyalists encountered fewer internal restraints, reducing corrective feedback. Confidence hardened into inflexibility. As alternatives narrowed, political maneuvering gave way to confrontation. The system responded defensively, seeking stability through exclusion rather than accommodation. Charisma, once a tool of ascent, became a signal of danger to those responsible for preserving continuity.

The Roman experience demonstrates that charisma becomes a liability when it replaces rather than supplements institutional trust. Personal loyalty accelerates polarization by redefining politics as allegiance rather than governance. Strongmen did not fail because they lacked supporters, but because their mode of leadership repelled the cooperation necessary to rule. Charisma promised control, yet delivered isolation.

Conclusion: Popularity Is Not Power

The Late Roman Republic demonstrates with unusual clarity that political popularity and political power are not synonymous. Crowds can cheer, mourn, and mobilize, yet governance depends on structures that extend beyond public enthusiasm. Rome’s strongmen retained loyal followings even as their capacity to rule diminished. What failed was not belief, but coordination. Institutional authority eroded when elite cooperation collapsed and undecided actors withdrew their consent.

This collapse did not occur because Roman citizens suddenly rejected charismatic leadership. Nor did it hinge on moral awakening or ideological conversion. It unfolded as moderates, administrators, and opportunists recalculated their interests in the face of instability. Once confidence in governability waned, loyalty shifted quietly and decisively. Popular support proved emotionally potent but politically insufficient when detached from institutional alignment.

The Roman case offers a cautionary lesson about the limits of mass enthusiasm. Charisma can energize politics and accelerate reform, but it also polarizes systems that depend on shared restraint. When leadership becomes personalized and spectacle substitutes for negotiation, power narrows even as attention expands. Strongmen surrounded themselves with supporters while losing the coalitions required to sustain rule. Isolation, not opposition, marked the final stage of republican collapse.

Rome’s transformation reminds us that political systems endure not through passion alone, but through cooperation among those positioned between extremes. The decisive losses occurred not in the streets, but in council chambers, provinces, and moments of withheld allegiance. Popularity persisted. Power moved elsewhere. The Republic did not fall because the crowd disappeared, but because the middle chose stability over devotion.

Bibliography

- Flower, Harriet I. Roman Republics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian. Caesar: Life of a Colossus. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

- Gruen, Erich S. The Last Generation of the Roman Republic. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974.

- Lintott, Andrew. The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Millar, Fergus. The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998.

- Morstein-Marx, Robert. Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- North, John. “Democratic Politics in Republican Rome.” Past & Present 126 (1990): 3–21.

- Plutarch. Life of Antony. In Parallel Lives. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1920.

- Slootjes, Daniëlle. “Review: Local Elites and Power in the Roman World: Modern Theories and Models.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 42:2 (2011): 235-249.

- Sommer, Michael. “Empire of Glory: Weberian Paradigms and the Complexities of Authority in Imperial Rome.” Max Weber Studies 11:2 (2011): 155-191.

- Southern, Pat. Mark Antony: A Life. Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 1998.

- Syme, Ronald. The Roman Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939.

- Tan, James. “Political Cohesion and Fiscal Systems in the Roman Republic.” Frontiers in Political Science 4 (2022).

- Yakobson, Alexander. Elections and Electioneering in Rome. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1999.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.20.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.