Greek fears of Persian law did not arise from systematic observation of Achaemenid governance, nor from sustained engagement with imperial legal practice.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Foreign Law and the Language of Fear

Greek writers of the fifth century BCE repeatedly described the Achaemenid Persian Empire as a regime defined by alien and oppressive law, a political order in which obedience replaced consent and command displaced civic deliberation. In Greek literary and political imagination, Persian rule appeared as the antithesis of freedom itself: subjects obeyed decrees issued by distant rulers rather than laws generated within the community of citizens. This portrayal became a durable feature of Greek self-definition, especially in the aftermath of the Persian Wars, when contrasts between Greek autonomy and Persian domination were sharpened into moral absolutes. Persian power was rendered legible through the language of law, imagined as arbitrary, imposed, and culturally alien. Yet these depictions raise a central problem. They describe a form of legal tyranny that does not align with what is known of Achaemenid administrative practice, suggesting that Greek descriptions of Persian law functioned less as reportage than as ideological boundary-drawing.

In Greek political thought, law was not merely a mechanism of governance but a marker of collective identity. To live under one’s own laws was to be free; to live under the laws of another was to be enslaved. As a result, “foreign law” functioned as a symbolic threat rather than a descriptive category. When Greek authors spoke of Persian law, they were often articulating anxieties about heteronomy, loss of civic agency, and the fragility of self-rule. The fear was not that Persians would enforce specific statutes upon Greek communities, but that submission to imperial authority would dissolve the moral distinction between citizen and subject.

Greek depictions of Persian legal oppression were shaped less by observation than by cultural projection rooted in Greek political insecurity. Achaemenid Persia governed through a system that famously allowed local peoples to retain their own legal, religious, and customary traditions, intervening only where stability or revenue was threatened. Evidence from across the empire, including Anatolia, Mesopotamia, and Judea, demonstrates a pragmatic imperial strategy that favored accommodation over homogenization. Persian authority operated through recognition of difference rather than its eradication. The Greek panic over Persian law reflects a profound misalignment between representation and reality, revealing how fear of domination can arise even where tolerance is the governing principle.

By examining Greek portrayals of Persian law alongside the actual practices of Achaemenid governance, this seeks to recover the ideological function of “foreign law” in the Greek imagination. Fear of Persian legal domination served as a rhetorical tool through which Greeks clarified their own values and anxieties, particularly concerning freedom, citizenship, and cultural integrity. In this sense, the language of fear reveals more about the accuser than the accused. Persian law became a symbol of imagined domination even where tolerance was the rule, illustrating how cultural anxiety can transform accommodation into threat.

Greek Political Identity and the Centrality of Law

For Greek poleis, especially in the fifth century BCE, law was inseparable from political identity and collective self-understanding. Nomos was not merely a set of enforceable rules but the visible expression of communal autonomy and moral order. To participate in lawmaking, adjudication, and enforcement was to belong fully to the political community, to be recognized as a citizen rather than a dependent or outsider. Law marked the boundary between freedom and subjection, not because it eliminated constraint, but because it embodied self-constraint. Obedience to law signified participation in authority rather than submission to it. This conception shaped Greek assumptions about freedom itself, which was defined not by the absence of limits but by living under laws one had a role in authoring and sustaining.

In democratic Athens, this relationship between law and identity was intensified and institutionalized. Legal equality among citizens, public participation in juries, and open deliberation in the assembly reinforced the idea that law emanated from the demos itself. Courts were not distant instruments of coercion but civic spaces in which citizens enacted sovereignty. Obedience to law was framed as obedience to oneself, mediated through collective judgment rather than imposed command. This conception produced a sharp moral contrast with systems imagined to operate through decree or hierarchy. Any political order in which law appeared to originate outside the citizen body could only be understood as oppressive, regardless of its practical effects or administrative efficiency.

Greek political culture also associated law with masculinity and civic virtue. The capacity to deliberate, judge, and enforce law was linked to ideals of rational self-mastery and public responsibility. To live under the law was to demonstrate moral discipline; to live under another’s law was to be feminized, infantilized, or enslaved. These cultural associations intensified Greek sensitivity to the idea of imposed law, transforming it into a marker of humiliation rather than a neutral administrative arrangement.

This emphasis on legal autonomy made Greek political identity acutely vulnerable to anxiety about heteronomy. Empire, by definition, implied hierarchy, distance, and asymmetry of power, threatening the immediacy of citizen control that Greeks regarded as the foundation of freedom. Even benevolent or tolerant rule could appear suspect if it displaced local decision-making or obscured the source of authority. As a result, Greek thinkers tended to interpret imperial systems through the lens of legal domination, assuming that rule over diverse populations necessarily entailed the imposition of alien law. The fear was not simply political but existential, rooted in the possibility that autonomy could be dissolved without overt coercion.

Greek tragedy, historiography, and political rhetoric reinforced these assumptions. Persian rulers were portrayed as issuing commands rather than laws, and subjects were depicted as obeying out of fear rather than civic obligation. Such portrayals did not require empirical accuracy to be effective. They functioned as moral contrasts that clarified Greek values by negation. Law was central not because Persians lacked it, but because Greeks required an external foil against which to define their own political ideals.

Understanding the centrality of law in Greek political identity is essential to interpreting Greek accounts of Persian governance. The fear of “foreign law” did not arise from sustained observation of Achaemenid administration, but from the symbolic weight law carried within Greek self-conception. Persian authority became legible to Greek audiences only when translated into the language of imposed law and lost autonomy. In this translation, cultural anxiety replaced administrative reality, and law became the medium through which Greeks articulated their deepest fears about subjection, control, and the fragility of self-rule.

Greek Portrayals of Persian Law as Tyranny

Greek writers consistently depicted Persian governance as the rule of arbitrary command rather than law, framing the Achaemenid Empire as a political order fundamentally opposed to freedom. In these accounts, Persian authority flowed downward from the king as personal will, enforced through fear rather than consent or civic participation. Law, as Greeks understood it, was either absent or fatally distorted, replaced by decrees that bound subjects without their involvement or assent. This portrayal allowed Greek authors to sharpen the contrast between their own systems of public deliberation and an imagined Persian world of obedience and silence. Persian law became a rhetorical device through which Greeks affirmed their own political values by negation.

Herodotus provides some of the most influential and enduring formulations of this image. Persian kings are shown issuing commands that carry the force of law simply because of their position, while subjects comply without debate, appeal, or institutional restraint. Even when Persian customs are described in detail, they are framed as expressions of despotism rather than as coherent legal traditions rooted in administration or precedent. The distinction between custom, decree, and law is blurred deliberately, allowing Greek audiences to interpret Persian order as fundamentally illegitimate. What mattered was not descriptive accuracy, but the moral clarity such depictions offered. By presenting Persian governance as command masquerading as law, Herodotus reinforced the idea that legality without participation was indistinguishable from tyranny.

This literary strategy relied heavily on the trope of oriental despotism. Persian rule was portrayed as excessive, hierarchical, and feminizing, with law functioning as an instrument of domination rather than a shared civic framework. Greek freedom, by contrast, was defined through moderation, reciprocity, and legal self-restraint. By casting Persian law as tyranny, Greek writers transformed administrative distance into moral inferiority. Empire itself became proof of injustice, and diversity of rule was collapsed into uniform oppression.

Tragedy and political rhetoric reinforced these images with particular emotional force. Persian rulers appear on stage as figures of unchecked authority, surrounded by courtiers rather than citizens, while their subjects speak in voices marked by fear, lamentation, and submission. These portrayals were not designed to educate audiences about Persian administration, but to dramatize Greek anxieties about power unbound by law. The Persian king served as a cautionary figure, embodying what Greeks feared most: authority severed from communal authorship and restraint. Tyranny was not merely foreign; it was the imagined endpoint of political degeneration.

The cumulative effect of these portrayals was the creation of a stable imaginative framework in which Persian law could only be understood as coercion. Greek authors did not need to deny the existence of Persian legal practices; they simply reclassified them as commands unworthy of the name nomos. In doing so, they transformed cultural difference into moral hierarchy. Persian law became tyranny not because of what it did in practice, but because of what Greeks feared becoming if their own legal autonomy were lost.

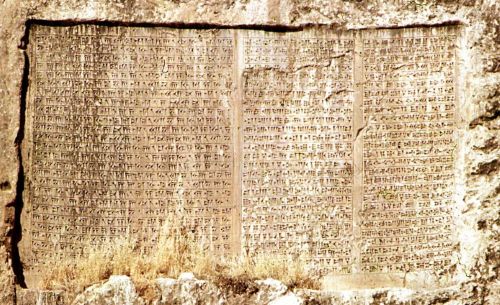

Achaemenid Governance and Legal Pluralism

Contrary to Greek portrayals of Persian rule as legally monolithic and coercive, the Achaemenid Empire governed through a system of pronounced legal pluralism that was both intentional and durable. Rather than imposing a uniform imperial legal code, Persian administration depended on the preservation and recognition of local laws, customs, and religious traditions across an empire that stretched from the Aegean to Central Asia. This approach was not a sign of weakness or administrative indifference. It reflected a coherent imperial philosophy that understood stability as the product of accommodation rather than homogenization. Law under Persian rule functioned as a means of sustaining order across difference, not as a tool for cultural domination or forced assimilation.

At the heart of this system was the satrapal structure, which delegated authority to regional governors responsible for taxation, security, and imperial oversight while leaving local legal practices largely intact. Satraps did not replace indigenous courts, councils, or customary norms with Persian statutes. Instead, they operated alongside existing institutions, intervening primarily to ensure loyalty to the crown, the flow of tribute, and the maintenance of peace. Local elites retained legal authority in matters of family law, contracts, religion, and communal governance. This division of authority allowed imperial power to coexist with legal autonomy, reinforcing Persian legitimacy without requiring intrusive control over daily life.

Persian kings consistently represented themselves not as lawmakers in the Greek sense but as guarantors of justice across difference. Royal inscriptions emphasize order, truth, and proper conduct rather than legal innovation. The king’s role was to uphold a moral and cosmic balance, not to legislate uniform statutes for disparate peoples. This self-presentation aligned with administrative practice. Imperial authority set boundaries within which local laws could operate, stepping in only when disorder threatened the stability of the whole.

Evidence from Mesopotamia illustrates this pattern clearly. Babylonian legal traditions, including contract law, inheritance practices, and temple administration, continued uninterrupted under Persian rule. Legal documents from the period show continuity in language, procedure, and institutional authority. Persian oversight did not displace these systems but relied upon them, integrating imperial interests into existing legal frameworks rather than dismantling them.

This pluralistic approach extended across the empire. In Anatolia, Egypt, and Central Asia, local elites retained legal authority and religious leadership under Persian suzerainty. Imperial administration depended on cooperation rather than replacement. The empire’s durability over two centuries was not achieved through legal coercion but through a flexible governance model that treated diversity as a stabilizing asset rather than a liability.

Understanding Achaemenid legal pluralism is essential to reassessing Greek fears of “foreign law.” Persian governance did not seek to impose alien legal systems on subject populations, nor did it conceptualize law as an expression of cultural domination. Authority was imperial, but law remained local. Greek depictions of Persian tyranny reveal a profound disconnect between imperial reality and ideological representation. What Greeks imagined as imposed law was, in practice, a system designed to minimize disruption by preserving legal continuity. The fear of Persian law exposes Greek cultural anxiety rather than Persian administrative intent.

Judea, Law, and Imperial Accommodation

Judea under Achaemenid rule offers one of the clearest concrete examples of Persian legal accommodation in practice. Far from imposing an alien legal system, Persian authorities treated local religious and legal traditions as instruments of stability. The province of Abar-Nahara was governed not through cultural replacement but through recognition of inherited norms, particularly those tied to temple administration and communal law. Judea’s experience demonstrates that Persian authority operated through preservation rather than coercion, challenging Greek assumptions that empire necessarily entailed legal domination.

Persian policy toward Judea is most visible in its support for the restoration of the Jerusalem Temple and the reestablishment of local religious institutions. Royal decrees attributed to Cyrus and his successors authorized rebuilding efforts, returned sacred objects, and recognized the centrality of Jewish law to communal order. These actions were not expressions of religious sympathy, but calculated acts of governance. By anchoring authority in existing legal and cultic structures, Persian rule reduced resistance and ensured predictable administration. Law functioned as a stabilizing force precisely because it remained local.

Jewish legal tradition under Persian rule was not subordinated to imperial statute, and this autonomy extended beyond ritual observance into the broader organization of communal life. Community governance, ritual law, and internal adjudication continued to operate according to inherited norms preserved through priestly authority and scribal transmission. Persian officials did not legislate religious practice, codify Jewish law, or attempt to integrate Judean legal norms into a standardized imperial system. Instead, imperial oversight focused narrowly on loyalty to the crown, the regular payment of tribute, and the maintenance of regional security. This separation between political sovereignty and legal autonomy exemplifies the Achaemenid approach to rule, in which empire governed over law rather than through it, allowing local legal systems to sustain social order without threatening imperial authority.

The Judean case also reveals the limits of Greek knowledge and conceptual vocabulary regarding Persian administration. Greek writers, distant from the everyday functioning of imperial provinces, interpreted Persian authority through categories shaped by polis life and civic self-legislation. Law, in Greek political imagination, could only exist as either self-authored or forcibly imposed. The possibility that an empire might allow subject peoples to govern themselves legally while remaining politically subordinate did not fit this binary. Judea’s experience exposes this conceptual blind spot, illustrating how accommodation could be misread as domination and tolerance interpreted as latent coercion by observers committed to a narrow understanding of political freedom.

Judea stands as a direct empirical counterexample to Greek fears of “foreign law.” Persian rule did not seek to erase local legal identity or replace it with imperial command. Instead, it preserved communal law as a means of maintaining order and legitimacy. The persistence of Jewish legal tradition under Persian sovereignty underscores the extent to which Greek panic over Persian law reflected cultural anxiety rather than administrative reality. Fear of imposed law, in this context, reveals more about the Greek imagination than about Achaemenid governance.

Fear of Law as Cultural Projection

Greek fear of Persian law functioned less as a response to empirical governance than as a projection of internal cultural anxiety. The image of imposed, alien law allowed Greek writers to externalize their own fears about political dependence, loss of autonomy, and the fragility of civic self-rule. Persian authority became a screen onto which Greek concerns were projected, transforming distant imperial administration into a symbolic threat. What was feared was not Persian law as practiced, but the idea of law detached from communal authorship.

This projection was reinforced by the centrality of law to Greek political self-definition and by the narrow conceptual limits of Greek political imagination. Because freedom was understood as obedience to laws one helped create, any system in which law appeared to originate outside the citizen body was interpreted as inherently oppressive. Greek observers collapsed the distinction between political sovereignty and legal practice, assuming that subjection to imperial authority necessarily entailed legal coercion. Empire itself was read as a condition of heteronomy, regardless of how law functioned within imperial structures. The possibility that political subordination could coexist with meaningful legal autonomy did not fit comfortably within Greek frameworks shaped by the polis, direct participation, and face-to-face governance.

Fear of “foreign law” also allowed Greeks to stabilize their own identity through contrast. By imagining Persian subjects as legally coerced, Greeks could reaffirm their own status as free, rational, and self-governing. The portrayal of Persian law as tyranny served an internal purpose, reinforcing civic cohesion and moral superiority at moments of political uncertainty. Cultural difference was translated into legal threat, and administrative complexity was reduced to moral binary. In this way, anxiety masqueraded as critique, and projection replaced analysis.

Understanding fear of law as cultural projection clarifies the persistence of Greek misrepresentation despite contradictory evidence. Persian tolerance did not alleviate Greek anxiety because the fear was not grounded in observation or experience. It was grounded in the symbolic function law played within Greek political imagination as the guarantor of freedom and identity. Persian governance threatened Greek self-understanding not by imposing alien law, but by revealing that freedom and legal autonomy were not universally defined or structured. The fear of foreign law reveals less about Persian rule than about Greek insecurity, exposing how deeply identity can shape perception even in the face of empirical counterexample.

Law, Empire, and the Limits of Greek Knowledge

Greek representations of Persian law were shaped not only by ideological anxiety but by genuine and persistent limits of knowledge. Most Greek authors had no direct access to the internal workings of Achaemenid administration, and their understanding of imperial governance was filtered through geographic distance, intermittent contact, and the distortions of conflict. Information about Persia circulated through oral reports, diplomatic encounters, mercenary experience, and wartime storytelling, all of which favored anecdote over institutional analysis. Law, already charged with symbolic meaning in Greek political thought, became an especially vulnerable category. It could be transformed into shorthand for domination without requiring close examination of how authority actually operated within the empire.

The sheer scale and administrative complexity of the Achaemenid Empire further strained Greek comprehension. Imperial governance functioned across vast distances, multiple languages, and layered systems of authority that bore little resemblance to the compact, face-to-face institutions of the polis. Greek political categories, developed for small-scale civic communities, were poorly suited to interpreting a system in which sovereignty, administration, and law were deliberately separated. Where Greeks expected legislation, they encountered oversight. Where they anticipated uniform command, they found negotiated accommodation. Lacking conceptual tools to describe this arrangement without undermining their own political assumptions, Greek writers defaulted to moralized caricature.

Wartime context intensified these distortions. The Persian Wars did not merely generate hostility but hardened interpretive frames that persisted long after active conflict ended. Persia became the paradigmatic enemy against which Greek freedom was defined, and enemy governance was read through the logic of opposition rather than inquiry. Under these conditions, Persian tolerance could be dismissed as deception, and administrative restraint reinterpreted as latent tyranny. Law, already imagined as the site where freedom or enslavement was decided, became a convenient vessel for projecting moral judgment onto an opponent whose political system remained distant and opaque.

Herodotus himself illustrates both the reach and the limits of Greek understanding. His Histories preserve valuable information about Persian customs, court rituals, and administrative practice, yet his interpretive lens remains shaped by Greek political assumptions. Persian decision-making is often narrated as personal command, even when it reflects collective processes or procedural norms unfamiliar to Greek audiences. The complexity of imperial governance is flattened into scenes of royal decree because such scenes resonated with Greek expectations about monarchy, authority, and law. Knowledge is present, but interpretation remains constrained.

Greek ignorance was not merely factual but structural. The polis-centered worldview privileged immediacy, participation, and visible authorship of law as the foundation of legitimacy. An empire that governed indirectly, tolerated difference, and allowed law to remain local while sovereignty remained imperial challenged these assumptions at a fundamental level. Rather than revising their political categories, Greek writers often reaffirmed them by misreading imperial practice as despotism. Law became the language through which this misrecognition was expressed, transforming unfamiliar governance into moral threat.

Recognizing the limits of Greek knowledge does not require dismissing Greek sources, but it does require reading them with methodological restraint. Their portrayals of Persian law tell us less about Achaemenid administration than about the constraints of Greek political imagination under conditions of rivalry, fear, and identity formation. Empire was reduced to tyranny because Greek conceptual tools could not accommodate pluralism without destabilizing their understanding of freedom itself. In this gap between partial knowledge and entrenched interpretation, cultural anxiety filled the void, and law became the symbol through which misunderstanding hardened into conviction.

Conclusion: When Fear of Law Reveals the Accuser

Greek fears of Persian law did not arise from systematic observation of Achaemenid governance, nor from sustained engagement with imperial legal practice. They emerged from the central role law played in Greek political identity and from the anxieties that accompanied the preservation of autonomy in a world of expanding empires. Persian rule became intelligible to Greek audiences only when translated into the moral language of law and tyranny, a translation that revealed Greek assumptions more clearly than Persian realities. What Greeks feared was not legal coercion as such, but the erosion of a political self-understanding built on participation, visibility, and communal authorship.

The persistence of this fear, even in the face of evidence of Persian tolerance, underscores the power of projection in political thought. Achaemenid legal pluralism challenged Greek binaries of freedom and domination by demonstrating that sovereignty and law could be separated without annihilating local autonomy. Rather than revising their categories, Greek writers resolved this tension by reclassifying difference as oppression. Persian accommodation was reimagined as despotism because acknowledging it would have destabilized Greek claims about the uniqueness and fragility of their own political systems.

This pattern illustrates a broader dynamic in which accusations of “foreign law” function less as descriptions than as acts of boundary enforcement. By framing Persian governance as legally tyrannical, Greeks reaffirmed the moral coherence of the polis and justified resistance to imperial power. Fear of law became a tool of self-definition, transforming cultural anxiety into political critique. The imagined threat of imposed law provided clarity where complexity might otherwise have unsettled identity.

Greek panic over Persian law reveals the accuser more than the accused. The Achaemenid Empire did not govern through legal erasure, nor did it seek to remake subject populations through uniform statute. Greek fears arose instead from the symbolic weight law carried within their own political imagination. When law becomes the primary marker of freedom, any unfamiliar legal arrangement appears as domination. The history of Greek representations of Persian law stands as a reminder that fear of legal otherness often discloses the insecurities of those who voice it, rather than the intentions of those they fear.

Bibliography

- Briant, Pierre. From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1996.

- Cartledge, Paul. Ancient Greek Political Thought in Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- —-. The Greeks: A Portrait of Self and Others. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Carugati, Federica, Gillian K. Hadfield, and Barry R. Weingast. “Building Legal Order in Ancient Athens.” Journal of Legal Analysis 7:2 (2015), 291-324.

- Fleck, Robert K. and F. Andrew Hanssen. “Engineering the Rule of Law in Ancient Athens.” The Journal of Legal Studies 48:2 (2019), 441-473.

- Flower, Michael. Theopompus of Chios: History and Rhetoric in the Fourth Century BC. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Grabbe, Lester L. A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period, Volume 1. London: T&T Clark, 2004.

- Hall, Edith. Inventing the Barbarian: Greek Self-Definition through Tragedy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Hansen, Mogens Herman. The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991.

- Harrison, Thomas. Divinity and History: The Religion of Herodotus. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- —-. “Herodotus’ Perspective on the Persian Empire.” Electrum 29 (2022), 23-37.

- Herodotus. Histories. Translated by Robin Waterfield. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Lockhart, Laurence. “The Constitutional Laws of Persia: An Outline of Their Origin and Development.” Middle East Journal 13:4 (1959), 372-388.

- Ober, Josiah. Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- —-. The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Salehi-Esfahani, Haideh. “Rule of Law: A Comparison between Ancient Persia and Ancient Greece.” Iranian Studies 41:5 (2008), 629-644.

- Tuplin, Christopher. Achaemenid Studies. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1996.

- Waters, Matt. Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.13.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.