The archaeological and historical record demonstrates that ancient body modification was rooted in coherent systems of meaning rather than personal ornament alone.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Body modification in the ancient world was neither marginal nor ornamental. It served as a primary means through which communities expressed hierarchy, ritual obligation, kinship, and cosmology. Across early civilizations, the body functioned as a surface upon which meaning could be inscribed, manipulated, or revealed. Practices such as tattooing, piercing, scarification, cranial shaping, and ritual bloodletting were integral to how societies articulated identity and belonging.1

The earliest securely documented forms of tattooing appear on naturally preserved bodies from the fourth millennium BCE. The copper-age mummy known as Ötzi, discovered in the Tyrolean Alps and dated to around 3300 BCE, bears carbon pigment tattoos arranged in lines near joints, suggesting therapeutic or symbolic intent.2 Comparable early evidence appears in Egypt. Infrared imaging conducted by the British Museum revealed figural tattoos on two predynastic mummies from Gebelein, dated between 3350 and 3017 BCE, including motifs resembling a wild bull and a Barbary sheep.3 These discoveries confirm that tattooing was a practiced and culturally meaningful form of bodily inscription long before the emergence of formal writing systems.

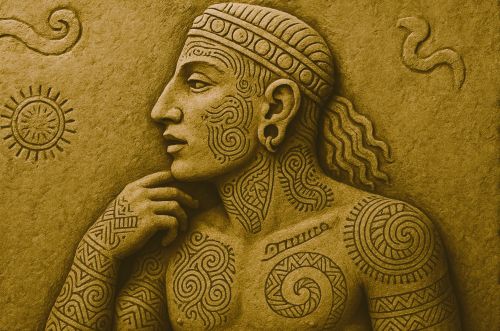

Other forms of modification, including piercing, scarification, and cranial deformation, likewise carried layered meanings. Archaeological and textual evidence from Egypt, India, Mesoamerica, and numerous African regions demonstrates that piercing could signify status or ritual participation. Scarification often marked transitions into adulthood or membership within a lineage. Cranial shaping, especially among the Maya and Andean civilizations, constructed visible distinctions of identity from infancy onward. Each of these practices, though varied in method and purpose, reflects an underlying principle shared across many ancient societies: the deliberate shaping of the body as an extension of cultural life.4

Together these practices reveal a deep human impulse to encode social and spiritual meaning directly onto the body. Far from being peripheral customs, body modifications formed part of a coherent visual language that bound individuals to communities and communities to their cosmologies. Examining these practices across regions shows the body not as passive matter but as an active site where identity and belief were quite literally made visible.5

Tattooing in the Ancient World

Tattooing is among the earliest securely documented forms of permanent body modification, and the archaeological record establishes its presence across several ancient cultures. The oldest direct evidence comes from the naturally preserved body of the Tyrolean Iceman, whose more than sixty carbon pigment tattoos date to around 3300 BCE. These lines, arranged near joints and along the spine, suggest therapeutic or symbolic functions based on their placement.6 The clarity of preservation in Ötzi’s skin provides an unusually detailed view of early tattooing techniques and purposes, allowing scholars to verify both the age and distribution of the markings.

Egypt provides equally significant early evidence. Infrared imaging conducted by the British Museum revealed figural tattoos on two predynastic mummies from Gebelein, dated between 3350 and 3017 BCE. The tattoos depict what appear to be a wild bull and a Barbary sheep on the male mummy, and linear motifs on the female.7 This discovery alters earlier assumptions that predynastic tattooing was largely a female practice and expands the chronological range of Egyptian tattooing by more than a millennium. It also confirms that figural imagery, rather than abstract patterning alone, held meaning in early Nile-region communities.

Later Egyptian evidence demonstrates that tattooing persisted into the New Kingdom. Osteoarchaeologist Anne Austin documented extensive tattoos on the remains of women at Deir el-Medina, dated to the thirteenth century BCE. These tattoos include symbolic motifs such as wadjet eyes, serpents, and geometric patterns arranged along the abdomen, thighs, and lower back.8 Their placement near reproductive organs and joints suggests connections to fertility, protection, or ritual affiliation. These finds provide direct evidence that tattooing formed part of lived religious and social identities among working and priestly women in the Theban region.

Comparative research shows that tattooing cannot be reduced to a single function across cultures. While Egyptian tattoos often appear linked to ritual protection or social affiliation, other traditions used tattooing to mark lineage, achievement, or status. Ethnographic parallels from Polynesia and Indigenous North America have long been studied, but cross-cultural analyses emphasize the need to rely only on securely dated archaeological or documented historical evidence when addressing the ancient world. Scholars warn against projecting modern ethnographic interpretations backward without material confirmation.9 This caution ensures that cultural meaning is grounded in verifiable contexts rather than generalized assumptions.

Tools and techniques associated with tattooing further illuminate its development. Archaeological studies have identified bone tattooing implements in the Near East and early North Africa, although their interpretation depends on context and residue analysis. In Egypt, pigment studies confirm the use of carbon-based materials such as soot, while comparative research from Nubia and the Levant suggests that incision followed by pigment application was widespread in early periods.10 Such findings help reconstruct how ancient peoples created tattoos and how they selected materials that would endure within the skin.

Taken together, the archaeological, technological, and art historical evidence demonstrates that tattooing in the ancient world was a deliberate and meaningful act rooted in specific cultural frameworks. It served social, religious, therapeutic, and symbolic purposes that varied across time and region. The early examples from Ötzi, predynastic Egypt, and New Kingdom Thebes form a coherent body of evidence that establishes tattooing as one of the oldest and most enduring forms of bodily inscription.11

Piercing as Social, Ritual, and Aesthetic Practice

Piercing appears in the archaeological and textual record across a wide geographic range, and its functions varied according to cultural context. In ancient Egypt, pierced ears are visible in both artistic depictions and excavated jewelry from Old Kingdom through New Kingdom contexts. Elite men and women are regularly shown wearing earrings, and surviving artifacts made of gold, faience, and semi-precious stones confirm that ear piercing formed part of established adornment traditions.12 Because Egyptian art consistently encoded markers of rank and identity, the depiction of pierced ears in elite portraiture suggests that piercing acted as a visual indicator of status.

Beyond Egypt, securely documented evidence from ancient South Asia shows that ear and nose piercing formed part of longstanding cultural practice. Literary references in early Sanskrit texts describe nose and ear ornaments in association with both regional customs and feminine adornment. The Nāṭyaśāstra, a treatise on dramaturgy dated to the early centuries CE, includes references to bodily ornamentation that help establish the antiquity of piercing traditions in the subcontinent.13 Archaeological recovery of gold and terracotta ear ornaments from sites such as Taxila further confirms their early use. These materials demonstrate that piercing in South Asia was neither marginal nor superficial, but an established element of bodily presentation tied to region and identity.

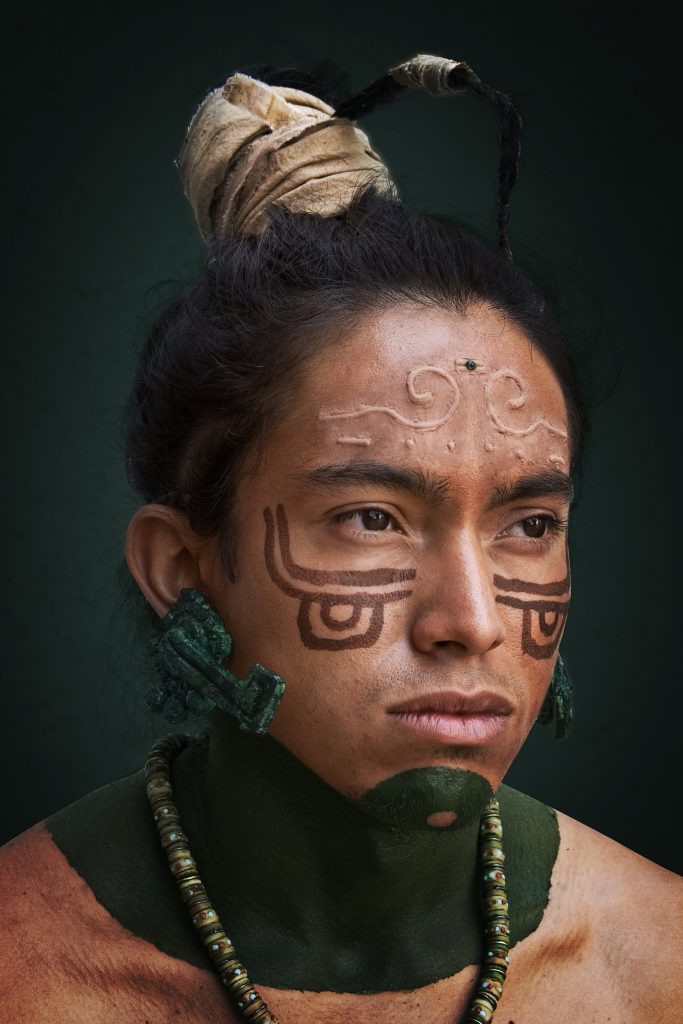

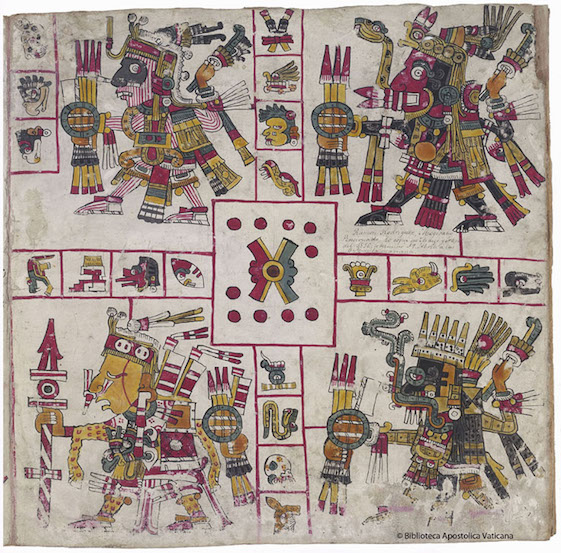

Mesoamerica offers a distinct and well-documented ritual dimension to piercing. Aztec and Maya iconography, supported by ethnohistorical accounts from the early colonial period, depict elite individuals performing tongue and ear piercings during bloodletting ceremonies. These acts formed part of devotional practice meant to nourish deities and sustain cosmic order. Codices such as the Codex Borgia and the Codex Mendoza, together with descriptions by Bernardino de Sahagún, confirm that piercing was not merely decorative. It functioned as an act of ritual self-offering that carried political and spiritual weight in elite circles.14 Such evidence provides clear, primary documentation for piercing as sacred performance.

Archaeological finds across Eurasia further expand the documented presence of piercing. Burial contexts in the Near East and the Caucasus have yielded metal earrings and piercing implements dated to the Bronze and Iron Ages. Although some artifacts cannot be tied to specific individuals, their placement in graves indicates their use as personal adornment. Studies of Scythian and Sarmatian burials show that pierced ears were common among high-status individuals, evidenced through gold and bronze ornaments recovered alongside other elite regalia.15 These finds demonstrate that piercing had a long and continuous presence across nomadic and settled societies alike.

Interpreting the meaning of piercing requires careful attention to context because similar practices carried different implications across cultures. In some societies, piercing clearly tracked social differentiation, while in others it anchored religious duties or reinforced kinship ties. Comparative anthropological studies caution against universalizing interpretations, emphasizing instead that meaning must be reconstructed from verifiable material or textual evidence specific to each cultural system.16 When understood within its own context, piercing emerges not as a universal aesthetic choice but as a culturally situated practice embedded in systems of belief and hierarchy.

Taken together, the archaeological, iconographic, and textual evidence shows that piercing served as a flexible and multivalent form of body modification. Whether in elite Egyptian adornment, South Asian cultural practice, or Mesoamerican ritual bloodletting, piercing acted as an outward signifier of social position, spiritual responsibility, or communal identity. Its durability across time and place underscores its importance as a key component of ancient embodied expression.17

Scarification and the Embodied Language of Social Identity

Scarification, unlike tattooing or piercing, leaves raised patterns produced through cutting, abrasion, or burning, and these scars form durable visual markers of identity. Because soft tissue rarely survives in archaeological contexts, most ancient evidence comes from securely attributed historical descriptions, early ethnographic documentation, and comparative analyses grounded in material culture. Scholars emphasize that scarification functioned as a socially communicative practice rather than a purely decorative one.18 It created permanent signs that conveyed lineage, age grade, or spiritual affiliation through patterns recognizable within a specific cultural system.

African societies provide the most securely documented traditions of scarification with deep historical roots. While much of the evidence is ethnographic rather than archaeological, colonial-era drawings, curated objects, and early written accounts supply verifiable premodern documentation. Scarification among Central African groups encoded clan identity and social maturity in ways that could not be separated from political structure or cosmology.19 These written sources, supported by museum holdings of documented scarification tools, confirm that the practice served as a durable map of social belonging.

In the Nile Valley, textual and artistic evidence suggests related practices, though not always identical to later African forms. Certain depictions in Egyptian art show patterned markings on Nubian subjects, and classical sources including Herodotus refer to body marks among peoples south of Egypt. While these accounts must be read with caution, they provide verifiable observations of scarification-like practices in antiquity.20 Archaeologists working in Nubia have recovered tools and pigments that point to bodily marking traditions, although distinguishing tattooing from scarification requires careful interpretation. These materials support the conclusion that body marking played a role in expressing cultural difference between neighboring regions.

Scarification frequently accompanied rites of passage across societies where it is documented. Anthropological studies describe how initiation ceremonies used scarification to signal transition from childhood to adulthood, creating visible and lifelong indicators of social transformation. The permanence of these marks distinguished them from temporary forms of adornment and affirmed an individual’s incorporation into a defined social category.21 Unlike tattooing, which often emphasized imagery, scarification relied on texture, forming a tactile and visible script that communicated through the body’s altered surface.

Despite the diversity of patterns and meanings, scarification consistently functioned as a social text embedded within cultural frameworks. It inscribed memory, obligation, and identity onto the body in ways that could be read by insiders while simultaneously asserting difference to outsiders. When examined through verifiable historical, textual, and material evidence, scarification emerges not as a marginal practice but as a central means of shaping and displaying the social self in many ancient societies.22

Cranial Modification and the Social Construction of the Body

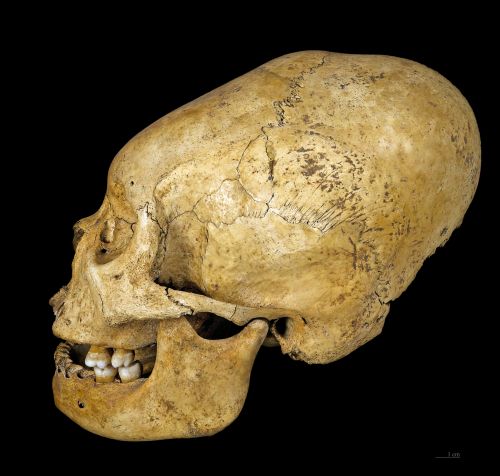

Cranial modification, also known as deliberate cranial deformation, is one of the most archaeologically visible forms of ancient body alteration because it leaves permanent changes to skeletal structure. Scholars have documented this practice across the Americas, Eurasia, and parts of Africa, and its distribution suggests independent development in multiple regions rather than diffusion from a single origin.23 The alteration typically occurred during infancy, when the skull remained malleable, and produced forms ranging from elongated vaults to flattened foreheads. These modifications functioned as deliberate expressions of cultural identity that were recognizable within specific social groups.

The Maya present one of the best-documented ancient traditions of cranial modification. Archaeological studies of burials from the Classic period (250–900 CE) show a range of cranial shapes produced through binding apparatuses, cradleboards, and pressure techniques applied shortly after birth.24 Iconographic sources, including stelae and painted ceramics, depict elite individuals with elongated foreheads that correspond to skeletal remains, confirming that the practice carried social significance. Scholars have noted that modified skulls are more common in elite or high-status contexts, suggesting that cranial shaping formed part of broader systems of aesthetic and political differentiation.

In the Andes, cranial modification appears across several cultural groups, including the Paracas, Nazca, and Inca. Osteological analyses show standardized forms created through consistent binding methods, which indicates that these shapes were not accidental or incidental but culturally prescribed.25 Excavations in the Paracas Peninsula have uncovered cemeteries where specific cranial forms cluster among certain lineages or regional groups, underscoring the role of head shaping in expressing identity and territorial affiliation. These findings reveal a strong connection between body form and sociopolitical organization in Andean societies.

Beyond the Americas, cranial modification is also documented in parts of the ancient Near East and Eurasian steppe. Analyses of burials from the Late Roman and early medieval periods show elongated skulls associated with Hunnic and Sarmatian populations.26 These modified crania appear in both adult males and females, implying that cranial shaping signaled group belonging rather than military status alone. Written accounts from late antiquity make reference to distinctive physical traits associated with steppe groups, and osteological evidence corroborates these descriptions. The combination of textual and skeletal sources provides a secure foundation for interpreting the practice within broader patterns of migration and identity formation.

The global distribution of cranial modification demonstrates that humans in multiple ancient societies used the body as a structured medium for expressing collective identity. The permanence of these skeletal alterations created visible markers that signaled belonging, lineage, or social standing throughout an individual’s life. When examined through securely dated burials, verified iconographic sources, and historical accounts, cranial modification emerges as a central practice through which ancient peoples constructed and displayed identity in ways that were literally embodied.27

Ritual Modification and the Manipulation of the Sacred Body

Ritual body modification represents one of the clearest intersections between physical alteration and religious belief in the ancient world. In several societies, modifying the body through piercing, cutting, or painting created a channel of communication between humans and the divine. Unlike adornment meant for social display, ritual modification invoked cosmological relationships and established the body as a vessel through which sacred obligations were fulfilled. Archaeological, iconographic, and textual evidence shows that these actions formed part of structured ceremonial systems rather than informal or decorative practices.28

Mesoamerica provides some of the strongest primary evidence for ritual modification. Maya and Aztec elites engaged in bloodletting rituals that involved piercing the tongue, ears, or genitals with obsidian blades, stingray spines, or bone tools. These ceremonies are documented in codices such as the Madrid Codex and the Borgia Codex, as well as on carved monuments and painted vessels.29 Blood offered through piercing was believed to nourish gods and maintain cosmic balance, and depictions of rulers performing these acts underscore their political and spiritual responsibilities. The physical modification was therefore inseparable from conceptions of rulership, time, and divine order.

Body painting also played an important ritual role in several ancient cultures. In Egypt, pigments such as red ochre, malachite, and carbon black were applied during funerary rites, festivals, and priestly ceremonies. Residue analyses on palettes and cosmetic tools confirm the long-standing use of pigments in ritual contexts.30 In Greece, body painting formed part of Dionysian and funerary traditions, with textual references indicating that painted bodies signaled transformation, liminality, or divine association. These examples show that modifying the body’s surface was a deliberate act that signaled ritual readiness or separation from ordinary life.

Ritual hair modification appears in multiple ancient systems. Egyptian priests shaved the entire body, including eyebrows, as part of their purity regimen, a practice documented in temple inscriptions and supported by classical commentators such as Herodotus.31 In contrast, some Indigenous groups in North America adopted ritual hairstyles that signaled ceremonial status or preparation for warfare. While meanings varied widely, verifiable evidence consistently shows that manipulating the hair functioned as an embodied declaration of ritual identity, one that visibly separated individuals from everyday roles.

Other forms of ritual modification, such as limb decoration or temporary constriction, also carried ceremonial significance. In some societies, bands of fiber, leather, or cloth were tied around arms or legs during initiation ceremonies, producing temporary impressions or marks that signaled participation in specific rites.32 Unlike permanent modifications such as tattooing or scarification, these temporary acts created short-lived transformations that accompanied transitions between ritual states. Together, these practices reveal that ritual modification created embodied markers of sacred experience, altering the physical form to manifest a connection to divine or communal forces.

Aesthetic and Social Modifications: Adornment, Paint, and Constriction

Aesthetic body modification in the ancient world encompassed a wide range of practices that altered appearance without necessarily producing permanent change. These include body painting, intricate hairstyles, limb constriction, and the use of adornments such as jewelry and cloth. Although less archaeologically conspicuous than cranial deformation or scarification, these practices formed part of daily self-presentation and social identity. They contributed to visual hierarchies that signaled status, age, gender, occupation, or affiliation, and they functioned as flexible markers that could shift according to ritual cycles, seasonal events, or interpersonal interactions.33

Body painting held particular significance in several ancient civilizations. In Egypt, pigments such as red ochre and malachite were applied not only during ritual events but also as part of routine cosmetic practice. Excavated cosmetic palettes from Naqada through New Kingdom contexts show consistent patterns of pigment preparation, and residue analyses confirm the presence of mineral compounds used for both health and aesthetic enhancement.34 In ancient Greece, references in literary texts suggest that painted bodies appeared in festivals associated with Dionysus, while in various Indigenous American societies, body paint communicated clan identity, ceremonial roles, or readiness for warfare. These examples show that color served as a socially readable language that transformed the appearance of the body for specific contexts.

Hairstyling similarly functioned as a visible and socially coded form of modification. Egyptian tomb reliefs and statuary depict elaborate wigs crafted from human hair, fiber, and beeswax, used by both men and women to signal status or ceremonial readiness.35 In the ancient Mediterranean more broadly, hairstyles identified age, marital status, and political allegiance. Roman literary sources describe youth cutting their hair as a rite of passage and matrons adopting distinctive hairstyles that communicated respectability. Because hair grows and can be restyled, it allowed individuals to shift identities according to circumstance while maintaining recognizable cultural norms.

Limb constriction represents a more ambiguous form of modification because its material traces are rarely preserved. In certain societies, cords or bands were tied around arms or legs for ritual purposes, creating temporary impressions or altering circulation during specific ceremonies. While the practice is better documented in later ethnographic records, scholars acknowledge that similar binding traditions existed among earlier societies, especially where textiles and flexible materials formed part of ceremonial dress.36 Evidence from preserved Andean textiles, which include narrow woven bands, supports the interpretation that constriction or compression formed part of ritual attire. Although these marks were temporary, the act of constriction created an embodied change that accompanied transitions in ritual status.

Adornment through jewelry and clothing also constituted a major form of social signaling. Egyptian excavations have revealed extensive collections of necklaces, bracelets, anklets, and rings made from gold, faience, and semi-precious stones. These items clearly indicate social rank, as their distribution correlates with elite burials and temple workshops known to be state-controlled.37 In the ancient Near East, cylinder seals worn on cords around the neck functioned not only as administrative tools but also as visible signs of bureaucratic authority and personal identity. Adornment therefore combined aesthetic preference with functional and political uses, rendering the body both a canvas and a credential.

Although these aesthetic and social modifications did not always leave permanent marks, they nonetheless operated as essential components of ancient identity formation. They enabled individuals to participate in cultural norms, display status, and signal affiliation through reversible transformations. When examined through securely documented artifacts, iconography, and textual sources, these practices reveal a sophisticated system of visual communication embedded within everyday life.38 Together with permanent forms such as tattooing and cranial shaping, they show that ancient bodily expression encompassed a wide spectrum of techniques, each contributing to the construction of social presence.

Comparative Analysis: Shared Themes and Cultural Divergence

Comparing body modification practices across ancient societies reveals several broad patterns that recur despite geographic separation. Tattooing, scarification, piercing, and cranial shaping all demonstrate that communities used the body to encode identity, hierarchy, and belief. Yet the meanings attached to each practice differed significantly according to cultural frameworks. Scholars argue that these practices illuminate not only aesthetic choices but also systems of social organization and cosmology that defined how communities understood the human form.39 The body functioned as a structured medium in which cultural codes were inscribed, creating a visible map of collective values.

One of the clearest distinctions concerns permanence. Some societies favored modifications that altered the body for life, such as cranial shaping or scarification, while others emphasized temporary transformations through paint, hair styling, or ritual adornment. These differences reveal divergent conceptions of identity. In cultures where permanence dominated, the body became an enduring statement of lineage and communal belonging. In others, the body shifted according to ritual cycles or social settings, suggesting a more fluid understanding of visible identity.40 This contrast underscores how societies conceptualized the relationship between the individual and the collective, and how bodily appearance reflected broader systems of continuity and change.

Another cross-cultural theme is the intersection of modification and authority. In Mesoamerica, ritual piercing and bloodletting were tied to political legitimacy because rulers were expected to demonstrate their connection to divine forces. In Egypt, tattoos and adornments helped mark ritual specialists, while elaborate wigs and jewelry reinforced elite identity.41 Across regions, those who held social or religious authority often underwent highly codified forms of bodily transformation. The body, therefore, acted as a visual register of power, one that made political and ritual roles immediately recognizable to others.

Differences also appear in how societies interpreted pain, endurance, and the body’s capacity for transformation. Scarification and ritual piercing often required controlled suffering, which created embodied narratives of resilience, maturity, or spiritual sacrifice. By contrast, aesthetic practices such as hair styling and body paint emphasized beauty, adornment, or alignment with communal norms.42 These distinctions show that body modification was not a monolithic category but a spectrum of practices that expressed distinct emotional and cultural values. They also reveal that bodily suffering, when present, carried meanings that were carefully prescribed within each society.

Despite these divergences, the comparative record shows that ancient peoples across the world shared a deep commitment to shaping the body as a site of meaning. The methods varied, but the underlying principle remained consistent: the body was never merely biological. It was social, symbolic, and often sacred. When analyzed through verifiable archaeological, textual, and anthropological evidence, body modification emerges as a universal yet culturally specific technology of identity.43 The ways ancient societies chose to inscribe, adorn, or reshape the body illuminate their values, beliefs, and understandings of what it meant to inhabit a human form.

Conclusion

The archaeological and historical record demonstrates that ancient body modification was rooted in coherent systems of meaning rather than personal ornament alone. Each practice, whether permanent or temporary, expressed a particular relationship between the individual and their community. In this sense, the altered body served as a visible archive of social roles, rituals, and inherited values. These inscriptions, cuts, pigments, shapes, and adornments were not peripheral embellishments but core elements of cultural identity.

Examining these traditions across multiple civilizations reveals that body modification consistently operated as a social language. Tattooing, piercing, and scarification allowed communities to communicate affiliation, maturity, and ritual obligation through visible codes that defined belonging. Cranial shaping made identity unmistakable even in skeletal remains, turning the body into a structural marker of lineage and rank. Temporary practices such as painting and hair styling performed similar work in more flexible ways, enabling individuals to shift their appearance according to ceremony or social role.

The diversity of meanings attached to these practices underscores the need to interpret each within its own cultural framework. Although the methods sometimes resembled one another, the symbolic systems that shaped them were distinct. A pierced tongue in Mesoamerica did not convey the same meaning as a pierced ear in Egypt, and scarification in Central Africa expressed different values than body paint in the Mediterranean world. The comparative evidence shows that ancient societies used the body to express identity in ways that were both universal in impulse and highly specific in form.

Taken together, these practices reveal that ancient peoples did not view the body as passive matter. They saw it as a surface for narrative, a medium for ritual, and a structure capable of holding social meaning. Through modification, they inscribed values, histories, and obligations directly onto human flesh. Understanding these traditions allows us to see not only how diverse ancient cultures shaped their members but also how the human body itself became one of the most enduring expressions of cultural imagination.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Michael T. Taussig, The Nervous System (New York: Routledge, 1992), 141.

- Marco Samadelli et al., “Complete Mapping of the Tattoos of the Tyrolean Iceman,” Journal of Cultural Heritage 16, no. 5 (2015): 753–58.

- Renée Friedman, “Natural Mummies from Predynastic Egypt Reveal the World’s Earliest Figural Tattoos,” Journal of Archaeological Science 92 (2018): 116-125.

- John W. Verano, “Cranial Modification and Identity in Ancient Peru,” Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 89 (2003): 1–23.

- Terence Turner, “The Social Skin,” in Not Work Alone: A Cross-Cultural View of Activities Superfluous to Survival, ed. Jeremy Cherfas and Roger Lewin (London: Temple Smith, 1980), 112–40.

- Samadelli et al., “Complete Mapping of the Tattoos of the Tyrolean Iceman,” 753–58.

- Friedman, “Natural Mummies from Predynastic Egypt Reveal the World’s Earliest Figural Tattoos,” 116-125.

- Anne Austin, “Of Ink and Clay: Tattooed Mummified Human Remains and Female Figurines from Deir el-Medina,” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 108:1-2 (2018): 33–44.

- Lars Krutak, Indigenous Tattoo Traditions: Humanity through Skin and Ink. Princeton: Princeton University Press, (2025), 12-29.

- Geoffrey Tassie, “Identifying the Practice of Tattooing in Ancient Egypt and Nubia,” Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 14 (2003): 85-101.

- Amy Louise Reeder, “Pigment and Pattern: Reassessing Early Evidence for Tattooing in North Africa,” African Archaeological Review 35 (2018): 475–91.

- Gay Robins, The Art of Ancient Egypt (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 45–47.

- Kapila Vatsyayan, The Square and the Circle of the Indian Arts (New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 1983), 112–14.

- Elizabeth Hill Boone, Cycles of Time and Meaning in the Mexican Books of Fate (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007), 88–95.

- Esther Jacobson, The Art of the Scythians: The Interpenetration of Cultures at the Frontier of the Greek World (Leiden: Brill, 1995), 60–63.

- Thomas A. Sebeok, ed., Approaches to Semiotics: Body Adornment and Social Meaning (The Hague: Mouton, 1975), 9–15.

- Andrews, Carol, Ancient Egyptian Jewelry, London: The British Museum, 1990, 7-11.

- Arnold Rubin, ed., Marks of Civilization: Artistic Transformations of the Human Body (Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History, UCLA, 1988), 13–19.

- Wyatt MacGaffey, Kongo Political Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000), 54–58; Jan Vansina, Paths in the Rainforests (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990), 127–30.

- Herodotus, Histories, trans. Aubrey de Sélincourt (London: Penguin Classics, 1954), 142–43.

- Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger (London: Routledge, 1966), 119–22.

- Enid Schildkrout, “Inscribing the Body,” Annual Review of Anthropology 33 (2004): 319–44.

- Vera Tiesler, “Studying Cranial Vault Modifications in Ancient Mesoamerica,” Journal of Anthropological Sciences Vol. 90 (2012): 1-26.

- Vera Tiesler, The Bioarchaeology of Artificial Cranial Modifications (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 56–74.

- Alejandro Tello and Ignacio La Cruz, “Cranial Deformation in Paracas Necropolises,” Latin American Antiquity 21, no. 1 (2010): 38–55.

- Joachim Werner, “Artificial Cranial Deformation Among the Huns and Alans,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 30, no. 3 (1968): 269–78.

- Heather J. Garvin, “Patterns of Identity in Cranial Modification,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 159 (2016): 622–35.

- Catherine Bell, Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 94–108.

- Mary Miller and Karl Taube, The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 58–64.

- Salima Ikram, Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2003), 72–76.

- Herodotus, Histories, 98–100.

- Rubin, ed., Marks of Civilization, 41–47.

- Joanne Eicher, ed., Dress and Ethnicity: Change Across Space and Time (Oxford: Berg, 1995), 1–18.

- Salima Ikram and Aidan Dodson, The Mummy in Ancient Egypt (London: Thames and Hudson, 1998), 117–22.

- Geoffrey Killen, Ancient Egyptian Furniture: Volume II, Boxes, Chests, and Hair (Warminster: Aris and Phillips, 1994), 54–59.

- Ann Pollard Rowe, Costume and History in Highland Ecuador. Austin: University of Texas Press, (2011), 23–31.

- Wolfram Grajetzki, Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt (London: Duckworth, 2003), 90–96.

- Mary Harlow and Ray Laurence, The Cultural History of Hair in Antiquity (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), 12–28.

- Chris Fowler, The Archaeology of Personhood (London: Routledge, 2004), 89–103.

- Sarah Tarlow, Ritual, Belief, and the Dead in Early Modern Britain and Ireland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 33–41.

- Joyce Marcus and Kent V. Flannery, The Creation of Inequality (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 128–34.

- Nancy Scheper-Hughes and Margaret Lock, “The Mindful Body,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 1, no. 1 (1987): 6–7.

- Emma L. Baysal, Personal Ornaments in Prehistory: An Exploration of Body Augmentation from the Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age, Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2019.

Bibliography

- Andrews, Carol. Ancient Egyptian Jewelry. London: The British Museum, 1990.

- Austin, Anne. “Of Ink and Clay: Tattooed Mummified Human Remains and Female Figurines from Deir el-Medina.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 108:1-2 (2018): 33–44.

- Baysal, Emma L. Personal Ornaments in Prehistory: An Exploration of Body Augmentation from the Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2019.

- Bell, Catherine. Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Boone, Elizabeth Hill. Cycles of Time and Meaning in the Mexican Books of Fate. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007.

- Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger. London: Routledge, 1966.

- Eicher, Joanne, ed. Dress and Ethnicity: Change Across Space and Time. Oxford: Berg, 1995.

- Fowler, Chris. The Archaeology of Personhood. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Friedman, Renée. “Natural Mummies from Predynastic Egypt Reveal the World’s Earliest Figural Tattoos.” Journal of Archaeological Science 92 (2018): 116-125.

- Garvin, Heather J. “Patterns of Identity in Cranial Modification.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 159 (2016): 622–35.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram. Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt. London: Duckworth, 2003.

- Herodotus. Histories. Translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt. London: Penguin Classics, 1954.

- Harlow, Mary, and Ray Laurence. The Cultural History of Hair in Antiquity. London: Bloomsbury, 2018.

- Ikram, Salima. Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2003.

- Ikram, Salima, and Aidan Dodson. The Mummy in Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson, 1998.

- Jacobson, Esther. The Art of the Scythians: The Interpenetration of Cultures at the Frontier of the Greek World. Leiden: Brill, 1995.

- Killen, Geoffrey. Ancient Egyptian Furniture: Volume II, Boxes, Chests, and Hair. Warminster: Aris and Phillips, 1994.

- Krutak, Lars. Indigenous Tattoo Traditions: Humanity through Skin and Ink. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2025.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt. Kongo Political Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000.

- Marcus, Joyce, and Kent V. Flannery. The Creation of Inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

- Miller, Mary, and Karl Taube. The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames and Hudson, 1993.

- Pollard Rowe, Ann. Costume and History in Highland Ecuador. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011.

- Reeder, Amy Louise. “Pigment and Pattern: Reassessing Early Evidence for Tattooing in North Africa.” African Archaeological Review 35 (2018): 475–91.

- Rubin, Arnold, ed. Marks of Civilization: Artistic Transformations of the Human Body. Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History, UCLA, 1988.

- Samadelli, Marco, et al. “Complete Mapping of the Tattoos of the Tyrolean Iceman.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 16, no. 5 (2015): 753–58.

- Scheper-Hughes, Nancy, and Margaret Lock. “The Mindful Body.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 1, no. 1 (1987): 6–7.

- Schildkrout, Enid. “Inscribing the Body.” Annual Review of Anthropology 33 (2004): 319–44.

- Tarlow, Sarah. Ritual, Belief, and the Dead in Early Modern Britain and Ireland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Tassie, Geoffrey. “Identifying the Practice of Tattooing in Ancient Egypt and Nubia.” Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 14 (2003): 85-101.

- Taussig, Michael T. The Nervous System. New York: Routledge, 1992.

- Tello, Alejandro, and Ignacio La Cruz. “Cranial Deformation in Paracas Necropolises.” Latin American Antiquity 21, no. 1 (2010): 38–55.

- Tiesler, Vera. The Bioarchaeology of Artificial Cranial Modifications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- —-. “Studying Cranial Vault Modifications in Ancient Mesoamerica.” Journal of Anthropological Sciences Vol. 90 (2012): 1-26.

- Turner, Terence. “The Social Skin.” In Not Work Alone: A Cross-Cultural View of Activities Superfluous to Survival, edited by Jeremy Cherfas and Roger Lewin, 112–40. London: Temple Smith, 1980.

- Vansina, Jan. Paths in the Rainforests. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990.

- Vatsyayan, Kapila. The Square and the Circle of the Indian Arts. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 1983.

- Werner, Joachim. “Artificial Cranial Deformation Among the Huns and Alans.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 30, no. 3 (1968): 269–78.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.20.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.